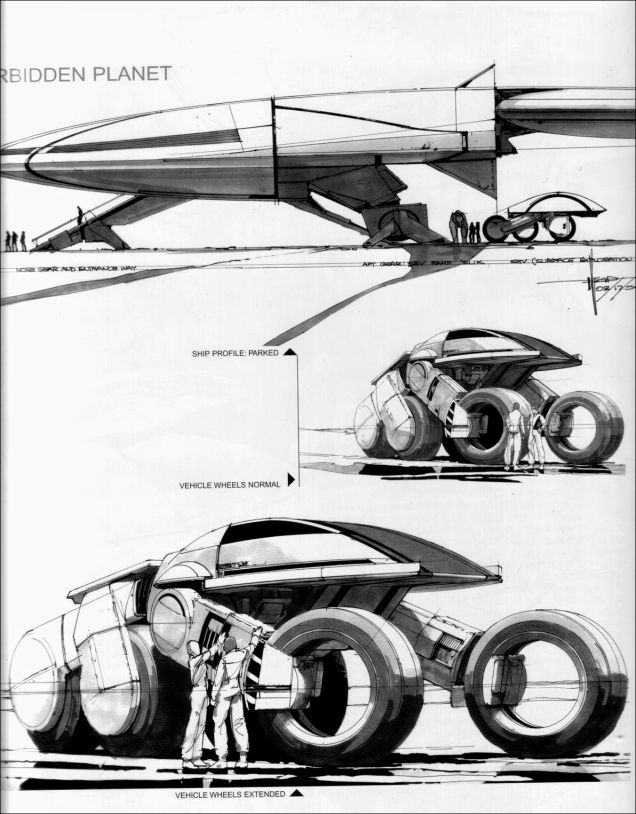

Genre: Sci-fi

Premise: When a distant civilization calls out to earth, humanity sends a ship to the planet to make contact. But all they find is a deserted world.

About: The original 1956 film is a classic and the first film to portray humans travelling together in a space ship. As recently as six years ago, James Cameron was intrigued with the possibility of making Forbidden Planet. Furthermore, the writer, J. Michael Straczynski, in typical Hollywood fashion, wanted to make a trilogy out of the property. While the project died not long after, we must remember that nothing in the movie business ever really dies. I’m sure the project will rise again.

Writer: J. Michael Straczynski

Details: 122 pages

Confession time. I’ve never seen Forbidden Planet. A lot of people will tell you that the 1950s film “holds up,” but come on. It’s 1950s special effects with cheesy 1950s acting. You might as well take out the sound and add dialogue cards.

Now from what I understand, in the original film, this ship the “Bellerophon” went to this mysterious planet but disappeared, and so earth sent a second ship to go figure out what happened to the Bellerophon. Well, with Straczynski turning this into a trilogy, he’s decided to follow the Bellerophon’s journey first, and that’s what this draft focuses on. I didn’t find out about the trilogy plans until after I read the screenplay, but it makes a whole lot of sense now, for reasons I’ll get to a bit. But first, a summary of the story…

The plot is pretty straight-forward. Aliens send earth a signal, along with instructions to build a ship and come visit them. There’s one small glitch though. The end of the signal cuts out, indicating that something may have happened while sending it.

Humanity builds a big giant ship, headed up by Captain Thomas Stearn. There’s like a 70 man crew, but the other two important players are Dr. Edward Morbius, a linguistics expert, and his wife (in title only), Diana Morbius. We sense a wee bit of tension between these three as Diana may or may not be secretly involved with Stearn.

So anyway, they fly to this planet, Altair-4, and the entire planet is one big city. But an abandoned city. There isn’t a single life-form around. However, when we see them leave the ship, we zoom in to notice little nano-robots entering their mouths as they breathe.

They then find an old museum where a robot named RBI (who they nickname “Robbie”) explains what he knows about the planet. Unfortunately, he’s been shut down for 800 years, so he can’t tell them why no one’s around.

Eventually, our emerging villain, Morbius, goes AWOL, and due to some connection with the nano-robots inside of him and this fully automated city, starts to actually control the planet, and quickly works to prevent the Ballerophon from leaving. Stearn will have to figure out how to stop Morbius if he’s going to save his crew, a task that’s looking less and less likely by the minute.

So when I started reading this, I noticed something pretty quickly. It was a cool idea. I was into it. But the story started to drag. Despite actually getting to the planet by page 30, our crew was still exploring it on page 70.

There’s a period after your characters get to the “problem spot” in your story where they start looking around and trying to figure out what’s going on. Blake Snyder of Save the Cat fame liked to call this the “Fun and Games” section, but that doesn’t really apply outside of comedies and family fare. Instead, I like to call this the “Discovery” section. This is where characters try to “discover” what’s going on in the environment they’ve been sent to.

“Discovery” should really only happen for about 15 pages (which is the same amount of time, I believe, Blake Snyder gives for his “Fun and Games” section). After that, the audience/reader starts to get restless and wants change. Imagine, for instance, in Alien, if our excavation crew went down on the Alien planet for 40 pages as opposed to 15. We’d get bored, right? We need to get to the next phase of the story, which is to bring the alien back to the ship.

But even if you’re required to stay in the location with your characters, you need to start introducing some heavier plot developments than simply finding a robot and chatting with him (as was the case here). I know there are a lot of Prometheus haters out there, but you’ll notice that the Discovery phase didn’t go on for long before a series of intense plot developments started to occur.

And that was my big problem with Forbidden Planet. It was that classic issue where you can sense that the writer is spreading his story out. He doesn’t have enough meat to cook with. At first I was confused about this. I knew Straczynski was a good writer. So why was he doing this?

Then I read about the planned trilogy and it all made sense. And hence, we have one of the biggest writing problems plaguing Hollywood today. It’s hard enough to come up with a great two hour story. But if you tell the writer, before he writes a word, that he actually has to write a SIX hour story, this is what you’re going to get. Long-drawn out plots with not enough happening.

This is the same thing that happened with the Hobbit trilogy. I remember watching the second Hobbit movie, and there came a point in the middle of the film with this big water-rafting barrel floating set-piece – and I thought to myself, “Yeah, this is a big set-piece but where are the stakes? Why is this important for the story?” It was empty because you could tell the writers were trying to cover the fact that they didn’t have a lot of story to begin with. The strategy, then, was to distract you with a big fat set-piece.

The solution to this problem is to always think of your script as a single script, even if you do plan to continue it with additional movies. Try to make it the best actual story on its own.

But there’s a bigger lesson here for screenwriters. And that’s to keep your story moving quickly. One thing I’ve found with young writers is that whatever you think is “fast-paced” is actually a lot slower on the page. It takes years and years for writers to actually understand how fast their story is coming across on the page.

So focus on moving the story along faster than you believe you have to. And that means introducing major plot points that push the story in new directions (a dangerous face-hugging alien on one of your characters) rather than small plot advancements that only have a minor effect on the story (finding a museum on your mysterious new planet).

Or, if you want me to put it simply: More shit needs to happen.

It’s kind of funny that we’re discussing this in the wake of a review about scripts that are ‘too complex.” But that’s not really what we’re talking about here. Complexity has little to do with writing bigger plot points that happen more frequently, which was the problem with Forbidden Planet. This script needed more meat. Maybe in future drafts, they’ll slaughter more cows to get it.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: If you feel like you’re biding time in your script, you probably are. Think about that for a moment. If you ever feel like you’re adding scenes to just keep the story alive and keep it going, those scenes will be dead on the page. Every scene should move the story forward in some purposeful way. If you ever feel like you’re biding time, go back to the point in the script where that “biding” started, and start over again.

Genre: Crime/Drama

Premise: When a young prostitute double-crosses some dangerous gangsters, she must team up with a mysterious seizure-ridden ex-KGB agent to escape them.

About: This is a writer-director project from Academy Award winner Stephen Gaghan (Syriana, Traffic) that he’s been trying to put together for a few years now. It’s had everyone attached from Robert De Niro to Chris Hemsworth. There was a time when Gaghan was the hottest writer in town. From 2000-2005, he was THE screenwriter to go to. Superstardom is impossible to maintain forever, though, and more recently Gaghan has been making money doctoring scripts (After Earth was one of the more recent projects he worked on). Gaghan has also jumped on the TV gravy train and has a new series on Fox premiering this year with Rainn Wilson (The Office) called Backstrom.

Writer: Stephen Gaghan

Details: 119 pages

Poor Crime-Dramas. They don’t fall into the new studio paradigm. Think about it. When was the last big-budget high-grossing crime-drama? What happened to movies like Heat? My guess is that the genre is too concept-light. You don’t have that big hook that gets butts in seats. These movies are more execution-dependent, which is the equivalent of saying to a studio, “I want to shoot my movie in black and white.”

I think the last big Crime-Drama was The Town, but that was sort of a magic act by Ben Affleck, as he marketed it as a heist movie, a much more marketable genre than Crime-Drama. Studios favor the “kissing cousins” of Crime-Drama, lovingly known as the “Crime-Thriller.” Stuff like Taken and The Equalizer – stuff that moves fast.

This is why I stress the “U” in GSU so much. Movies powered by urgency – the need to get the job done immediately – thrill audiences more. On the flip side, you don’t get the intelligence of a crime drama, the plot machinations that make you work harder for the answers, which can be more rewarding in the long run.

All of this, I’m guessing, is why The Candy Store has struggled to find financing. But it should be noted that everything comes back in Hollywood. If someone would’ve told me that the religious blockbuster would make a comeback three years ago, I would’ve told them to go part the Red Sea. So who knows, maybe The Candy Store will be the return of crime cinema.

Suki is a beautiful teenage Estonian girl who’s been trafficked across seas to Brooklyn, New York, where an opportunistic pimp named Chiddybang employs her. When Suki’s about to be killed for undercutting Chiddybang, some Transnistrians (I guess this is a real place) buy her away just in time.

It turns out that one of Suki’s clients is the president of one of the biggest Credit Unions in America. This Union fucked over the Transnistrians in a deal, and they want revenge. Using Suki’s access to the president, her job is to kill him, for which she’ll get her freedom.

Suki, not trusting that she’s going to walk out of this alive, seduces her handler, kills him, and makes a run for it. When the Transnistrians catch up to her, she’s saved by Swann, a former Russian agent who suffered a crippling brain injury leaving him seizure-ridden.

The two go on the run together, and the Transnistrians put together their A-team to find and kill them both. As Swann and Suki fall in love, he has to make a tough decision. Does he stay with Suki even though he knows it increases their chances of getting caught? Or send her away, giving her a chance to survive. Whichever route he takes will change his life forever.

The Candy Store is complex. The above summary is way streamlined. There are also entire flashbacks of characters in Transnistria. There’s a heroin-laced-with-Chernobyl-radiation subplot. There’s a storyline with a cowardly cop named Davis who loses his partner in a traffic-stop. And there’s some time manipulation too.

This weekend was a class in complex storytelling, as I read another screenplay, this one amateur, that was also dense and complicated. Here’s what I learned. Overly complex plots are the triple-axle routines of the screenwriting world. They’re extremely difficult to nail. If you’re going to go down this road, you have about ten pages to earn the benefit of the doubt. If you fail at earning this trust, we pull away the second things get confusing.

Gaghan earns the benefit of the doubt with a sophisticated persentation. There isn’t a single formatting or style issue in his script (for example, sometimes a writer will introduce a character without capitalizing their name – suicide in a complex script). The writing itself (phrasing, sentence structure, vocabulary) is strong. He knows to put heavy emphasis on orienting the reader (since it’s easy to get lost in complex stories). And characters all have strong memorable introductions.

For example, when Davis (the cop whose partner is taken) is introduced, Gaghan repeatedly hits on the fact that Davis is too cautious. He’s not brave enough. A lesser screenwriter introducing a cop will tell us nothing distinguishing about him. So we’ll never feel like we know the guy. When you’re writing a complex script with lots of characters, it’s essential that we remember all those characters. Strong distinguishing introductions are the key to that.

With that said, I can see why this is a hard sell. Audiences like puzzles. But The Candy Store is a 3-D puzzle. At one point we’re connecting two storylines from two different time periods in a very complex way.

There was this geeky kid in my high school who would always be on the computers day in and day out. And one day I asked him what he was working on. He told me he was developing a program of all the possible ways a human being could juggle 14 objects. At times, The Candy Store felt like it was written for that guy.

With that said, I was a big admirer of Gaghan’s scene-writing. I noticed ample use of some staple Scriptshadow techniques, such as the scene-agitator! When Davis approaches the stopped Transnistrian car, he commands his partner, Mahoney, to stay 30 degrees behind the rear-right wheel while he questions the driver.

As the driver starts giving Davis trouble, Mahoney keeps creeping up to look inside the back window. So Davis keeps having to turn and say, “Behind the wheel, Mahoney!” A lesser writer would’ve written this scene straight up, with Davis just talking to the driver. Adding the scene agitator amped up the tension another notch.

Also, from a technical standpoint, you can tell why this guy used to be the highest paid screenwriter in Hollywood. He really knows how to write. Ironically, that’s hurt him as of late. Hollywood is less and less interested in making these kinds of thoughtful movies, so you could argue that Gaghan is marginalized by his talent.

It reminds me of a couple of lines uttered by Hollywood execs. One famously said to a writer who turned in a draft: “Can you make it less… smart?” And then another exec warned the producer of The Princess Bride while he was pitching the project, “You gotta watch out for those William Goldman scripts. He’ll trick you with good writing.” As shocking as those quotes are, I can kind of understand them. The average moviegoer is not a Harvard grad. The average moviegoer doesn’t write juggling programs. The 1 percenters may love your movie. But there’s only 1 percent of them. What are you doing for the other 99?

Since we need balance in the marketplace, I hope The Candy Store gets made. It’s a solid script. But it’s definitely one that requires every ounce of your concentration.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: ”CUT TO” – CUT TO is one of those screenwriting phrases that isn’t used much anymore. If you write one scene and then write another scene, “cutting to” that other scene is assumed. However, the CUT TO can still come in handy when you’re writing scripts like The Candy Store, which follow multiple storylines. If you’re in a Brooklyn storyline for 15 pages, and then you need to cut to a completely separate storyline in Russia for 15 pages, a CUT TO can help the reader realize that a bigger jump is taking place. Without it, the jump can seem jarring. Like, “Whoa, how the hell did we end up in Russia so quickly?” Gaghan uses this to great effect in The Candy Store.

Five amateur screenplays. Read and tell us which one you liked best in the comments section. The winner gets a review. Also, feel free to offer constructive criticism to the writers.

Title: Molniya 7

Genre: Sci-fi, Adventure.

Logline: A reckless American astronaut risks everything to save seven world leaders trapped on board a crippled Russian space station before it crashes to Earth.

Why You Should Read: Hi Carson, my name is Tony and my passion for movies and screenplays spans decades. I’ve analyzed hundreds of works and read dozens of books on the craft — especially your book, which is the best ten bucks I ever spent, (wink, that’s worth a read, right? )

Your mission, Carson, should you decide to accept it, is to open the attachment to this email and immerse yourself in this high concept adventure about ingenuity, human spirit, and the will to live. I’ve kept the read under 100 pages, yet made sure every character has something to do — actors will love this, and I guarantee you that there is stuff in this screenplay that even you have never before seen. — As always, should you or any of your subscribers be caught or killed, the secretary will disavow any knowledge of your actions. This email will self-destruct in five seconds. Good luck, Carson.

Title: Quiescent

Genre: Sci-Fi Adventure

Logline: After a long-dormant Atlantean power station buried under Manhattan for thousands of years transforms the city with a mysterious time-meshing force, a vision-haunted Native American tunnel worker, a Columbia geology professor and his beautiful assistant team up with a hardened CIA agent to shut the pyramid down before it destroys the planet.

Why You should Read: Quiescent is a labor of love that took me years of research and a ton of rewrites to complete to my satisfaction. A sci-fi action adventure with a strong male and female protagonist, rich in history, memorable characters and deep metaphysical undertones. The threaded mysteries of time, ancient Atlantean technology and Native American spirituality make this tale an exciting thrillride.

Title: The Battle of Mirbat

Genre: War / Action

Logline: A retelling of the 1972 battle in which eight special forces soldiers defended an Omani town against 400 heavily-armed guerillas.

Why You Should Read: Described as a latter-day ‘Zulu’, the Battle of Mirbat is an incredible account of valor in the face of overwhelming odds. Classified for over thirty years, the soldiers’ mission has only recently become public knowledge but hopefully this script will bring their remarkable tale to a wider audience.

Title: Hadleyville

Genre: Western

Logline: An idealistic Easterner journeys to the burgeoning Western frontier where he falls for a prostitute and gets in the wrong with a powerful businesswoman, forcing him to learn how to leave his idealism and civility east of the Mississippi.

Why You Should Read: While I know the Western isn’t (and hasn’t been for arguably 40 years) the most topical, profitable, or popular genre it used to be, it still has a certain appeal for writers looking to explore ideas that other time periods aren’t necessarily designed for. The lawlessness, the encroaching border of a growing nation, the differences between Eastern civility versus frontier survival: Where else but the Western can you touch upon these concepts?

I’ve been writing screenplays for about five years now (and have a B.A. in screenwriting if that means anything…). I’ve had two features optioned and was hired to re-write a feature — all by indie producers looking for ever elusive financing. On top of that, I’ve been a quarter-finalist, semi-finalist, and finalist in national contests, including BlueCat, Big Break, and Table Read My Screenplay. Hadleyville, in fact earned me a spot as a finalist in The Black List’s 2014 Cassian Elwes Independent Screenwriting Fellowship — I’m sure the fact that it’s one of the (if not the) highest rated Western on blcklst.com gave me a leg up there.

The point is: I know how to write a screenplay, good ones even, but I’m looking to heave myself over the hump into the lands of “Very Good” and “Great.” I have my degree, hours of writing and reading scripts, and tips from Script Shadow to improve my writing — but there’s something I’m missing. Something I can’t get a bead on. And I have no doubt that you (and fellow Script Shadowers) can lead me into the sunsetting happy ending.

Title: The Irish Rover

Genre: Comedy

Logline: Looking to connect for the first time, a son and his drunk, crotchety, dying Irish father take an epic journey to Ireland to get him laid for a final Father’s Day goodbye fuck. Mayhem, whorehouses, shootouts, and rollicking celtic music all ensue in the process of this father and son finally coming together.

Why You Should Read: Fred Seton and I wrote this about two years ago. We took this to only one producer (who we love), got him attached, and the project fell apart. It’s just been sitting collecting dust ever since. Fred wrote “Pierre, Pierre” and recently had his script “Kid Leviathan” that he wrote with Peter Hoare on the Hit List. “The Irish Rover” is a raunchous romp of an Irish R-rated comedy that was originally dreamt up for Robin Williams and Chris O’Dowd to kill it in. The script is insane, wild, got heart, and beers for everyone. It’s a place where you’ll find Van Morrison, The Pogues, the Dubliners, and Ween all getting hammered and playing at the bar. Cheers to the Blarney Stone!

Get Your Script Reviewed On Scriptshadow!: To submit your script for an Amateur Review, send in a PDF of your script, along with the title, genre, logline, and finally, something interesting about yourself and/or your script that you’d like us to post along with the script if reviewed. Use my submission address please: Carsonreeves3@gmail.com. Remember that your script will be posted. If you’re nervous about the effects of a bad review, feel free to use an alias name and/or title. It’s a good idea to resubmit every couple of weeks so your submission stays near the top.

Genre: Spy Thriller

Premise (from writers): Based on true events. When Allan Pinkerton discovers a plot to assassinate Abraham Lincoln before his inauguration, the legendary detective and his most trusted operatives must race against the clock to prevent the murder of the president-elect.

Why You Should Read (from writers): When we came across this story, we were amazed it hadn’t been made into a film yet. Starring the most famous American president in history, the most renowned of real-life sleuths, and the first female detective in the United States.

Writers: Parker Jamison & Paul Kimball

Details: 119 pages

Note: The writers sent me a new version of the script implementing notes from the Amateur Offerings post. I thought I was reading that draft. It wasn’t until I put this post together that I realized I had read the original copy. I apologize about that. But it’ll be interesting to see if I noticed the same problems as you guys. And I welcome Parker and Paul to tell us what changes they made in the comments section.

I’ve never found Lincoln to be an interesting character due to him being wholeheartedly honest and good. These traits, while making him ideal to run a country, unfortunately make him a pretty boring subject. Movies (and books) like characters with flaws – characters who have amazing qualities which are offset by terrible ones. This creates an inner-struggle where the two opposing energies constantly work to balance each other out. An external conflict arises out of this struggle, which ends up making the character his own biggest enemy. Which is why the best stories usually require the hero to defeat himself to achieve his goal.

Bill Clinton would be a good subject for a movie. Here was a man who genuinely wanted to help the people of the world, yet wasn’t against breaking the heart of the person he loved most. Steve Jobs may end up being a good subject for a story. He built a series of products that gave people all over the world the power to be great. And yet by many accounts he was a horrible human being to the people who worked for him.

Unfortunately, the portrayal of Lincoln in The Baltimore Plot didn’t do anything to change my opinion of him. He still is, by and large, boring. He wants to do the right thing, which is great, but with every other aspect of him being perfect, there’s no dimension to his character. However, I think the writers can put Lincoln in a situation that’ll better bring out the most in the man. I’ll get to that in a moment. But first, here’s the plot.

The year is 1860. Abraham Lincoln has become president but hasn’t yet been sworn into office. While the North is pumped by Lincoln’s win, the South is pissed. With Lincoln threatening to rid the country of slavery, more and more southern states are seceding. A war is brewing.

It isn’t just the southern states that are pissed though. Baltimore, Maryland is wreaking havoc up in the North’s Eastern cluster, threatening to align itself with the South. There are rumors that a plot is forming to blow up the Baltimore railroad, which would hamper the North’s ability to ship supplies should a war break out.

To get to the bottom of these rumors, private detectives Kate Warne, Timothy Webster and Allan Pinkerton are hired to infiltrate Baltimore’s society and find out what the plan is. The stakes are raised when Lincoln himself announces that he’ll be taking the train up through Baltimore to Washington, where he’ll be giving his inauguration speech.

What the group finds is a small hive of terrorists who plan to assassinate Lincoln when he passes through Baltimore. But because the defiant Lincoln refuses to operate on rumors and fear, our group must come up with convincing evidence that the plot is real before Lincoln hits the city, a task that proves much more difficult the deeper they dig.

I’ll start by saying there’s definitely something here. This well-written logline caught my eye immediately and the writing is pretty good all the way through. These are also the writers of Barrabas, another script I liked. So I had my Baltimore Plot pom-poms on and believe me I was shaking them.

But as it stands, I’m not sure this script takes advantage of its premise enough. I feel like this idea was the Autobahn and we were puttering along in the right lane at 30 miles per hour. I think the first change Parker and Paul need to make is to think of this as more of a thriller. It reads way too casual at the moment.

The biggest reason for that is the Lincoln storyline. Kate and Timothy and Allan – they were the ones with the strong goals – to find the assassination plot in time to save Lincoln. So when we were with them, they were always acting. They were always trying to get something done.

When we came back to Lincoln (who we came back to A LOT – like 20 times) he had nothing to do but ride to his next destination and share a few expositional details with his campaign manager. His scenes were completely dead and they killed all the momentum whenever they came up.

I understand the need to include Lincoln. This screenplay is about an attempted Lincoln assassination. If we don’t get to know and sympathize with the guy, we won’t care what’s going on in the other storyline. But that doesn’t mean you can just plant him on-screen and let him mumble away. You need an exciting storyline for him as well.

That’s the way I like to look at parallel storylines (or subplots). Ask yourself, “What if I didn’t have the other half of this story to tell? Would this storyline be interesting enough?” If you cut out the Pinkerton assassination investigation, this would literally be about a guy travelling in a cart talking about the difficulties of campaigning. There’s not enough there.

So that’s the first change I’d make. Give Lincoln something he’s after, something that makes him active instead of reactive. I know you include him writing his speech but that’s a very malignant goal. It’s hard to make writing interesting in a film anyway (ironically) and we don’t even see him deal with that problem. We just hear him every once in awhile say, “I don’t know what to say.” It’s not enough.

The next problem is that there’s no character development in the story. Nor are there any interesting relationships in the story. It’s appropriate that this is called The Baltimore PLOT, because that’s all it is. Plot.

For example, there’s a moment near the middle of the script where Kate starts to tell Allan about how difficult it is to live a lie. It’s our first genuine moment inside a character’s head. But instead of a conversation emerging from that charged statement, there’s a vague acceptance from both characters and the scene is over.

And then there’s the relationships. This frustrated me the most because these kinds of movies allow for the most interesting relationships in film – relationships built on lies. Each of our three spies must get close with one of the terrorists in order to find out about the plan.

When you have a setup like this, you want the good guys to really connect and (at least on some level) LIKE the bad guys because that makes working with them all the more complicated. They like them but they have to deceive them. Not one of these relationships ever gets past the point of polite conversation. There are no true connections made.

Now I’m guessing Parker and Paul might argue that there wasn’t enough time for that. The script is already 120 pages and I’m asking for more. I’m going to let you guys in on a secret. It’s easy to find pages without bulking up your screenplay. You simply steal them from the subplots that aren’t as important. In this case, there are way too many scenes with Lincoln. We could get rid of half of those and have 15 new pages to play with.

Finally, in any spy movie, as the movie goes on, it’s essential that the spies find themselves in danger of getting caught. We have to get that sinking feeling that the bad guys are onto them and that they’re about to be discovered, for which they will surely be killed. I never felt anything close to that here except for ironically, at the very beginning of their infiltration (page 35 – when Hughes is onto Davies).

This scene embodied the script for me. Davies had made up a backstory that he was from Charleston, and one of the men he was with suspiciously says, “I’m from Charleston [too].” The man then starts questioning Davies about the town, of which Davies knows nothing about. Finally, we had an intense scene brewing here. I’m into it! But then, not more than 2 questions later with Davies’ lie ready to be exposed, another guy butts in and says, “You guys can deal with this later!” Right as we were revving up to 60 on the speedometer, we slammed on the breaks.

All of these things are fixable but they’re things writers need to know. You can’t write a story unless you keep an engine revving in all the storylines (not just one), unless you explore the character’s inner lives, unless you explore the relationships, unless you kick your character when he’s down instead of helping him back up (as was the case in the scene I just mentioned).

I like Parker and Paul. They have a knack for finding period stories that could make good movies. They still need to work on that storytelling though. I hope they take these notes to heart because if they stick with it, I think they have a real shot at working in this industry.

Script link (old draft): The Baltimore Plot

Script link (new draft): The Baltimore Plot

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: A great flaw to explore in “spy” movies is a loss of identity. You play the part of so many other people that you’ve forgotten who you are. I thought this is what we were going to see from Kate, but it didn’t happen. Might be something to look at for the next draft.

In honor of the year 2015, the year Star Wars returns to theaters, I’ll be writing a series of articles throughout the year to celebrate (and occasionally eviscerate), the greatest franchise ever. Enjoy! And may Christmas 2015 come faster than it takes Han Solo to do the Kessel Run.

The year was 1999. For movie nerds, that year marked the arrival of the single most anticipated film in movie history. It was the year The Phantom Menace came out. As millions of Star Wars fans left their local theater confused about how the magic of Star Wars could disappear faster than a womp rat on meth, I went back to my apartment looking for answers. Did George Lucas really just turn my favorite franchise into a bad Saturday morning cartoon?

In the time since, a lot has been dedicated to explaining why the movie didn’t work. But one of the things that doesn’t get mentioned that often – if it all – is the featured set-piece in the movie: the Pod Race.

The Pod Race, in George Lucas’s mind, WAS the movie. While good ole George was excitedly grinding everything from characters to sets into his digital blender, the Pod Race was the one thing he actually built stuff for. Every one of the vehicles in that race was a real prop.

So why is it, then, that a set-piece given so much attention, given so much screen time, given so much weight in the film, turned out to be one of the most boring races (and set-pieces) ever put on film? You watch that race and you’re not focusing on whether Anakin is going to win or not. You focus on why everything is so fucking boring.

The answer to this – once learned – will ensure that you never write a bad set-piece again (or at least one as bad as this). To be honest, set-pieces are typically one of the more boring parts of a screenplay. They’re often cut-and-dry “car speeds up, cuts other car off, joey shoots, brad ducks” blueprint-oriented scenes, rather than scenes written to actually evoke emotion (huge mistake). Truth be told, a lot of execs skim over set-pieces because there’s no important story information in them and it allows them to finish the read quicker.

If you’re doing your job, a reader will never EVER want to skim past a scene. They’ll be so caught up in your characters and your story that every little moment in that set-piece matters to them! So what did screenwriter George Lucas do so terribly to make this sequence, which should’ve been one of the classic all-time action scenes, so boring? Five things, to be exact. Let’s take a look at them.

“BORING MAIN CHARACTER” – I honestly don’t care if you’re the greatest set-piece writer in the world. If we don’t care about the person who’s at the center of the set piece, nothing you write in the set-piece will matter. I say this again and again on the site, but writers never do anything about it! Stop putting all your time into the set-piece and put it into creating an original, compelling, entertaining main character who we want to root for. Star Wars could’ve turned The Pod Race into a Bobbing For Apples contest and it would’ve worked if we cared about Anakin.

“NO MAIN CHARACTER FLAW” – In my newsletter, I talked about the importance of dealing with your characters’ internal issues in external ways. There’s no better time to do this than in a set-piece. And there’s no better way to explore it than through your hero’s unique flaw. If you’re going to build a ten minute race scene into your movie, it better challenge your hero’s flaw in some way. The problem here? Annakin didn’t have a flaw. He had some doubts, some fears. But he didn’t have a clear flaw. In contrast, Luke Skywalker didn’t fully believe in himself. That was his flaw. And that’s why him trusting himself in that ending Death Star sequence was so goose-bump inducing. A clear character flaw equals clear “external conflict” to play with during set-pieces, which creates a closer emotional connection between movie and viewer.

“THE BULLSHIT ARTIST” – Set pieces are your movie’s big performance numbers. In an action movie, they will often be what your movie is remembered for. So their reason for existing has to be airtight. The Rebels didn’t attack the Death Star in the first Star Wars, for example, because someone had a hunch that the base had a weakness. They had the Death Star plans that told them exactly how to destroy the base. In The Phantom Menace, we’re sold some cheap B.S. that winning this pod race (and using the prize money to fix their broken ship) was the only way for our group to get off the planet. As if two of the most important Jedi in the galaxy couldn’t have found an alternative way to leave. Once we know you’re trying to bullshit us on the reasoning for a set-piece’s existence, we turn on you quickly.

“OVER-COMPLICATION” – One of the things I continue to see amateur writers do wrong is needlessly overcomplicate their stories. Stop. Just stop! There’s always a simpler way. What you do when you over-complicate something, is you create confusion in the reader. If the reader is confused about why a big set-piece is going on, nothing in the set-piece matters. Before the Pod Race, Lucas injects an incredibly complicated bet between Qui-Gon and a local alien gambler that states if Anakin loses, the alien gets the pod-racer, but if Qui-Gon wins, he gets the pod racer, Anakin, and a part for his broken ship. The alien then doubles down, and if he wins, he gets the ship, the pod racer, the Anakin, and possibly Qui-Gon too. Qui-Gon comes back at him and doubles his own bet by asking for Anakin’s mom if they win as well. It’s so needlessly confusing, that by the time the race starts, we’re clueless as to what needs to happen. Confusion is NEVER EVER EVER good for your story and is especially bad right before a major sequence.

“REPETITION” – A set-pieces’ mortal enemy is repetition. If the cars that are chasing each other are doing the same dance for too long or if the bad guys and the good guys continue to shoot and duck in the same way over and over, we’re going to lose interest. A set-piece is a mini-movie. And just like any movie, you need to challenge and surprise your audience over and over again. Treat your set-piece like your portfolio and diversify. In the Pod Race, we were subjected to the same desert checkpoints again and again with little variety in the action or interactions between racers.

To me, the worst set-pieces are the ones that feel too technical. A set-piece is a complex series of organisms that have to work together. It’s great if you’ve come up with an imaginative set-piece. But if your hero isn’t battling his flaw as well (i.e. Neo fighting Smith in the subway when he didn’t believe in himself yet), then the set-piece feels empty. You might have the coolest location for your set-piece ever, but if you don’t establish big stakes and make those stakes CLEAR, we’re going to be confused about why the set-piece is happening (i.e. the race car set-piece in Iron Man 2).

Learn why the Pod Race, and other set-pieces like it, aren’t working, so that when it comes time to write your own set-piece, you’ll be ready to deliver.