I’m out of it, guys. I’ve got no energy left. That book release added a good 60 hours to my work week last week. This is how out of it I am. For the last two days, I believed that Luca Guadagnino and Yorgos Lanthimos were the same director. Would’ve bet my life on it.

So I can’t do a review today. Instead, I’m just going to tell you what I’m thinking for as long as my fingers will type. Cause I wanted to get a post up. The first thing I want to talk about is American Fiction. It won the screenwriting Academy Award so I had to watch it and I must say, it was a tale of two movies. One great movie, one terrible movie.

Everything that had to do with the fake book and his fake persona was AWESOME. By the way, that isn’t easy to do in 2024. In the real world, people would sniff this out in a second. Social media will bust anybody lying. They somehow got around that issue by ignoring it. And it worked!

But you know what didn’t work? EVERYTHING ELSE. I’m going to spoil this for you so you’ve been warned. Our main character has a father who committed suicide by shooting himself in the head. He has a mother who has Alzheimer’s. He has a sister, who we spend several scenes with, who then DIES OF A HEART ATTACK. And he has a gay drug-addicted brother too.

I just talked about this in my dialogue book (not too exhausted to get that link up apparently!). Melodrama. Going with the extreme version of every choice. Could ONE family member just be a normal person… alive!? That aspect of the script was so bad I actually expected it to be some meta thing that was part of the satire which would be explained in the end. “This is how you write a bad script!” That was going to be the theme or something and they were going to point out all the melodramatic choices that were made during the script. But NOPE. They didn’t do that. That was genuinely what the writer chose. AND HE WON AN OSCAR FOR IT!?

Can we even trust Oscar anymore? That shiny gold faceless liar.

By the way, in the end, when Jeffrey Wright’s character comes to the producer to do the adaptation of the fake book, is he coming to him as the real author or as his fake persona author? They didn’t make that clear.

I want to know why Scarlett Johansson is going to be in a Jurassic World movie. I thought she was done makin dat money and was entering a part of her career where she was going to do whatever artsy roles she wanted. Jurassic World is for a brand new up-and-coming actor, like Chris Pratt when he first signed on. It’s not for people like Scarlett. Scarlett don’t need monay. Help me out here. What she doin?

As I alluded to yesterday, Happy Gilmore 2 is coming. This is arguably the greatest comedic character ever created. And I know these 20-year gap sequels always suck but can a guy just hope? Because the actor who plays Shooter McGavin revealed to the world that when he last saw Adam Sandler, Sandler pulled out the script for Happy Gilmore 2.

Now, when I first saw this story, I thought two things. I thought, “Okay, that doesn’t mean anything. Sandler is making a million movies.” Second, I thought Shooter was doing Adam dirty. Cause announcing movies like that is a gigantic deal. If you betray a star’s trust who gives you that information as a secret, you could be blacklisted.

That’s when it hit me. There’s no way he would’ve done that unless he had Sandler’s permission. And the more I thought about it, the more I realized, IT WAS ALL PLANNED. They came up with this idea together. Not that I care. Because it means the movie is really coming. But I didn’t like to have to do all those mental gymnastics to get there.

Anyone want to give the plot of Happy Gilmore 2 a shot in the comments. Pretty sure at least half of you can come up with a better idea than Sandler’s writers. Ooooh, dis. Why you gotta be so mean, Carson?

What else is going on? Godgilla vs. King Kong – which already came out two years ago – just came out again and made 80 million bucks. This goes to show you that all you really need in a screenplay is a giant monster. Cause they re-released a movie that just came out 2 years ago and nobody noticed! They all went back to the theater. That tells me that every screenplay now needs a giant monster.

Giant Monster Showdown 2024? Hmmmm…. me shall think about it.

Finally, the most important news in all of Hollywood right now. Shakira saw Barbie with her sons and they all found it emasculating. And you know how I respond to that? “Finally somebody said it!” Cause it’s true of course. I’m just glad that somebody had the cajones to say it. Thank you Shakira.

And thank you to all of you!

And good night.

Cause I’m exhausted.

This is a game-changing newsletter. There is a special link within the newsletter that will change your screenwriting lives. I’m not going to spoil it. But let’s just say whoever receives this newsletter has a gigantic advantage over any screenwriter who doesn’t receive this newsletter. That’s how valuable the info inside that link is.

I also review a hot new spec screenplay that just sold to Warner Brothers. It is of the coveted “high concept low concept” variety. If you don’t know what that means, don’t worry. I explain it in the newsletter. But the short of it is that it’s a narrow sliver of the spec market that not many people know about. It includes scripts like “The Menu” and can lead to a quick sale.

You know I have to break down that Acolyte trailer, which received an unheard of 500,000 dislikes. Methinks Kathleen Kennedy might want to reevaluate her approach to Star Wars. Maybe go back to what the original fans loved about it? Just a thought. I also take on a bunch of other trailers, including my FAVORITE TRAILER OF THE PAST YEAR. This one warmed my heart. We also got a couple of surprise trailers, with Yorgos and Emma Stone reteaming for a new movie. And Jerry Seinfeld came out of nowhere to release his Pop-Tart movie trailer.

It’s a wonderful newsletter. If you’re not already signed up for my newsletters, my only question is, “Why?” E-mail me at Carsonreeves1@gmail.com and I’ll send it over to you.

Genre: Supernatural Thriller

Winning logline: A young war widow awakens naked on an Alaskan military base and fights for survival as she’s hunted by her father’s vengeful soldiers after a whole platoon was ripped apart overnight.

Winning Movie-Crossover Pitch: American Werewolf In London eats Memento

About: Not only did this logline + movie-crossover win the Showdown, it is the payoff of an earlier setup (to use a couple of screenwriting terms). You may remember that David sent in this logline for a consult and I published the process via an official post.

Writer: David Laurie

Details: 99 pages

Excellent job by David. He didn’t actually make it into the traditional showdown. For this showdown, I added one entry for the best movie-crossover pitch regardless of logline. That’s how David got in. And boy did he take advantage, winning the competition!

David is best known around these parts for the killer logline he won with in his last Amateur Showdown review. You can read the review of that script here.

Call of Judy didn’t blow us away but maybe She’s Got Claws will. Let’s find out!

A woman named Ivy in Afghanistan turns into a cat werewolf thing and kills a bunch of people. We then cut to Alaska where we meet Holly, who we will later find out is Ivy’s sister.

Holly wakes up outside some guy’s place. She walks in, looks at herself in the mirror, and sees a lot of blood. She stumbles outside and finds people looting apartment buildings. She meets up with some cops who take her to the station.

Once there, the Marines (or special forces) show up and claim to be looking for something dangerous. The head of the group is Holly’s father, whom Holly avoids. Although we don’t know why, we get the sense that she needs to stay as far away from this man as possible.

Figuring that whatever happened last night that resulted in her waking up naked and bloody is probably related to this marine infiltration, Holly slips out and meets up with one of the cops, Miguel, at his house. It’s unclear if Miguel knows she’s a cat-werewolf or if he just senses she wants to get away from these marines.

As the seemingly amnesia-ridden Holly tries to put the puzzle pieces of what happened back together, we occasionally jump back in time, where we meet other players. There’s Elizabeth, who hates Holly. We get the sense that Cat-Holly may have killed her husband. And then there’s Ivy, who Holly had some massive sibling rivalry with courtesy of their father. There are also some sinister scientific labs in their past.

When we jump back to the present, the Marines are hunting down Holly, who, taking a page from The Hulk’s book, is forced to become the cat once again to kill them off. Then Ivy herself arrives in town, turning this sibling rivalry into a primal to-the-death showdown. Or will Holly team up with her sister to take down the real problem here – Daddy? That’s the ultimate question that must be answered in.. She’s Got Claws.

The aim for this review is to be constructive because I know how much time and effort David has put into this craft. There’s an aspect to David’s writing that’s holding him back. And if he doesn’t fix it, he’s not going to advance to the next level.

That issue is LACK OF CLARITY in the writing. It’s what I experienced reading his last script. It’s what I experienced in our e-mail exchanges. And I experienced it again here.

It’s such an important issue that it’s hard for me to even diagnose today’s story because I probably only understood 60-70% of what was happening due to the lack of clarity in the writing.

What’s frustrating is that it’s hard to explain *why* there’s a lack of clarity. It’s not immediately apparent when you’re reading the script. David obviously knows how to construct sentences and paragraphs and he has a very active vocabulary and a vivid writing style.

But there are two areas in particular that kept causing problems.

One, sometimes there will be something in a sentence that either is highly unclear or, at the very least, unclear enough that I had to re-read it. This is fine if it happens a few times during the script. But it happened a few times every page.

Two, whenever a new situation arrived in the script, it wasn’t set up clearly enough. Again, there’s some gray area here. I *mostly* understood what was going on. But it always felt like the situations were presented clumsily. You could never quite see them as clearly as you wanted to.

Let’s go into some examples of both of these issues. We’ll start with the first one. Here are a series of sentences from the script.

-“Ali is still upright. Staring with one eye. Ivy pulls a face.”

What does “pull a face” mean? I *kind of* understand it. But I could be wrong. And that’s the problem. You want your reader to *definitely* understand. Not kind of understand.

-“He shoots. THREE RAPID. We SQUEAL. Jump back from the edge.”

Is “three rapid” referring to the shots? Then why not say, “THREE RAPID SHOTS?” It’s a small thing but it makes a big clarity difference.

-“We pad slowly round toward the front—“

I don’t know what this means. What does it mean when you “pad?”

-“He always nods hi to his reflection and has not exactly gelled with Alaska’s low key ways.”

This is in reference to a character intro. I don’t know what to make of this. You’re saying that this character, EVERY SINGLE TIME HE EVER WALKS NEAR A MIRROR, nods hi to the reflection? A) Why would someone nod hi to themselves? And B) Why would you nod hi to yourself in every mirror for the rest of your life?

-“Same Frankensteins. Same table. SNOW BLOWER THRUM drifts in.”

This is one of the easier lines to discern what’s going on. But still, “Snow blower thrum” is not an everyday phrase so when it’s presented in this quick staccato manner, it requires a re-read.

-“He cups his hand around his phone and rolls a die onto it.”

I’ve read this one a ton of times and I still don’t understand what it means.

I would implore David to stop writing in this style. I understand why he’s doing it. It’s part of his voice. But it’s undermining the clarity of the story. I would try to write a couple of scripts in proper English. Full sentences with subject, verb, and object. “John ate the taquitos.”

Cause I don’t think that these scripts are going to be clear enough until that change is made. Then, once you master that, you can start to pepper your voice back into your storytelling. Remember, your unique voice doesn’t matter if the reader can’t understand what you’re saying.

The second issue is an inability to clearly set up your major plot beats. For example, in Titanic, you don’t start with the ship hitting the iceberg. You have to set everything up first.

We meet Holly waking up from something bad happening. She walks into this apartment of a guy and sees herself bloody in the mirror. So my assumption was she slept with this guy then inadvertently turned into a were-cat and killed him. Then we go outside and, out of nowhere, the marines (or special forces) are in town cleaning the town out, supposedly to find this killer were-cat. But… she literally *just* killed someone and nobody knows about it yet. How are the marines there?

Later in the script, it’s mentioned that they came because she slaughtered a bunch of military people the previous night. So I go back and re-read that part of the script and realize that before we introduce Holly, we show glimpses of this animal killing people. So I thought, “Oh, okay. She didn’t kill the guy in the apartment. She killed people before she got to that apartment. But then where was the guy in the apartment? Did she kill him too? Was he gone on vacation?” It just seemed like it could’ve been set up clearer.

Holly is then taken to the police station, although I wasn’t entirely sure why. I think because she needed to be evacuated from town like everyone else?

From there, she sneakily exchanges texts with cop, Miguel, for some reason. I’m not sure why. I don’t know if she knows Miguel from before or if she just showed up in town yesterday? I don’t know! To be honest, I didn’t even know this was a military base UNTIL AFTERWARDS when I re-read the logline. When I was reading the script, I assumed it was a town.

She then sneaks away when the cops and marines aren’t looking and travels to Miguel’s house, where they meet up. I’m not sure why she goes there. I’m not sure why they need to team up.

This is what I mean when I say it’s like reading through fog. I would always feel as if I *mostly* understood why things were happening. But it was shaky enough that I was always doubting whether I was comprehending the moment.

As frustrating as this is for David to hear, it’s just as frustrating for me to explain because I want to fix this for him and I don’t know how. I wish it was as easy as “Do A, B, and C.” But there are minute details I haven’t identified that are playing into my inability to follow along.

All I know is that when I’m reading a good script, everything is crystal clear. Every word, every sentence, every beat, every action, every plot development, every character motivation. That’s not an issue that ever even comes up when I’m reading a good script. Clarity and presentation are a given. And that’s not happening here. It wasn’t happening in Call of Judy either.

Which means I can’t even assess the overall story.

I’m going to call on you guys here cause some of you are better at this than me. Read the first ten pages of She’s Got Claws. Tell me if you experience the same issues I had. If enough of you didn’t, I will concede I’m bad at reading. But, if you do, explain what you think is going on as specifically as possible. Because I want to help David. And I want to be better armed to help writers in the future who have this issue.

I still think this has movie potential. These dual-cat-human killers running around and ripping up Marines – I could see people paying for that. The script does have some gnarly imagery. But we need a way clearer AND cleaner story.

Script link: She’s Got Claws

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: You have to be aware of what your weaknesses are as a screenwriter and write around them. David has lack-of-clarity issues. When you have lack-of-clarity issues, you don’t want to write Memento, something with a lot of intricate flash-backing (which I didn’t get into in the review). We’re having a hard enough time following the present storyline. Prove you can tell a clear concise simple story first. Then you can get fancy.

Week 12 of the “2 Scripts in 2024” Challenge

We are writing a screenplay! And, believe it or not, we are almost done with our second act. You deserve a ribbon for that alone. Cause most writers never make it out of the second act.

If you missed out on previous articles in this series, I’ve listed them below.

Week 1 – Concept

Week 2 – Solidifying Your Concept

Week 3 – Building Your Characters

Week 4 – Outlining

Week 5 – The First 10 Pages

Week 6 – Inciting Incident

Week 7 – Turn Into 2nd Act

Week 8 – Fun and Games

Week 9 – Using Sequences to Tackle Your Second Act

Week 10 – The Midpoint

Week 11 – Chill Out or Ramp Up

If you’re at page 70 and are new to this screenwriting game, you’re probably intimidated as F&%$. I don’t blame you. It’s scary. We’re in no man’s land right now. But don’t worry. Based on our 110 page screenplay length, we’ve got only 15 pages left before we segue into our third act.

We’ve been covering the second act for a while now so it’s a good time to remind you what the five major components of the second act are.

- Hero should be moving towards their goal.

- You need to throw many obstacles at your hero to make pursuing that goal difficult.

- Explore unresolved relationships.

- Explore how your hero’s primary flaw is getting in their way.

- Move secondary character subplots forward (if you have them).

As long as you’re doing one of those five things, you’re moving in the right direction. The only difference between how you address those things NOW, towards the END of the second act, as opposed to the beginning of it, is that now everything is more intense.

Achieving the goal seems to get harder every second.

The obstacles only get bigger.

The relationships feel like they’re on the brink of extermination.

Your hero’s flaw is eating them alive, getting in the way of everything.

The subplots are all coming to a head.

But let’s get more specific.

What we know about the end of the second act is that it’s where our “DEATH SCENE” is. Not literally (although it can be). But the idea with the end of the second act is that our hero will have tried EVERYTHING to achieve his goal. And yet, he’ll have unequivocally failed. This is when both the protagonist and the audience should feel like “WE’VE LOST.”

So if we back up fifteen pages from that moment, we have to ask ourselves, “What leads up to that lowest point?” And usually, it’s when your hero has put in their BIGGEST PUSH. Or, at least, the biggest push they believe they’re capable of in this moment in time.

Due to them not yet overcoming their flaw, this late push doesn’t have the full force that our hero is capable of once they do overcome their flaw (which will happen in the climax).

The easiest genre to use to figure out how this works is the Romantic Comedy. We know that the boy is going to lose the girl at the end of the second act. That breakup is the equivalent of death. We see this in The 40 Year Old Virgin. Andy gets in a fight with Trish because she’s frustrated that he keeps avoiding sex. So she storms out, effectively ending their relationship.

So, how do we ramp up to that? We ramp up to that by writing scenes where Andy has opportunities to have sex with Trish but keeps backing out of them. They go on a date. The chemistry is off the charts. They get back to her place. It gets hot and heavy. But then Andy freaks out (cause he’s never had sex before) and makes up an excuse to leave. This makes Trish self-conscious and now she’s starting to doubt whether Andy is attracted to her.

Whenever you’re unsure what scene to write in a script, always go back to the character goal. The character goal will give you your answer. Because, chances are, you need to write a scene that brings you closer to that goal being achieved.

By the way, The 40 Year Old Virgin has a TON of secondary characters. So, much of its late second act is dedicated to covering those storylines. This option is available to you during this segment of the script if you have lots of subplots.

Let’s switch up the genre. In one of the best action movies ever, Predator, the end of the second act is everybody dead except for Dutch (Arnold Schwarzenegger). So, if you back up 20 pages, how do we get to that point?

We get to that point because Dutch and the three remaining survivors are making a run for it. That’s one of the interesting things about the goal in this movie. The goal isn’t to beat the Predator. It’s to escape it. But the Predator tracks the final four and kills them off one by one. So those are the scenes you would write in this section.

In the movie, Life of Pi, which follows a boy and a tiger stuck on a boat together, the end of the second act is them finally getting to land and the tiger jumps out of the boat and runs off.

Although the tiger doesn’t die, it is the equivalent of death for the boy because that tiger is who helped him get through this nightmare of being stranded at sea. And now it’s as if he was never there in the first place.

So you need to ask, what gets us to that point? Well, what’s the goal? The goal is to find land. The scenes that David Magee writes are the boy, Pi, trying to stay motivated. He’s stuck out in the ocean. His sails are busted. He literally can’t move. So the scenes are about looking for meaning in order to keep going.

One of those scenes has a major storm come (A GIANT OBSTACLE!) and essentially kill the tiger. The tiger is lifeless the next morning. Pi then nurses him back to health. It’s not as clear as Predator where our characters are physically moving towards their goal (escape the Predator). But because getting to land requires staying motivated, the goal is simply to find a reason to keep going. For Pi, that motivation is his tiger (Richard Parker).

The big lesson here is that you’re moving towards that DEATH at the end of the second act. So you want to go full-throttle towards that death. Whether it’s characters running away from a killer alien, a giant storm that nearly wipes out your hero and his tiger buddy, or your romantic interest pushing your hero towards something they’re terrified of doing.

Put your foot on the gas. Because in 15 pages, you’re going to hurl your hero into a spectacular crash you masochist!

:)

An excerpt from my upcoming book, “The Greatest Dialogue Book Ever Written”

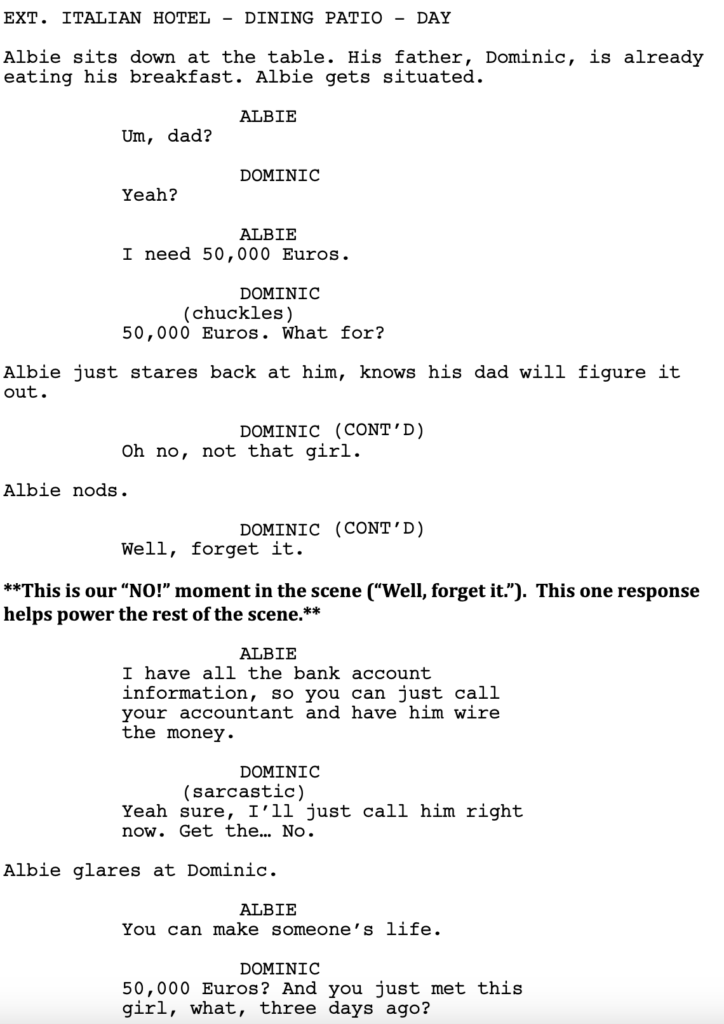

There was a time when I didn’t think I was ever going to finish this book. There were too many technical obstacles (mainly regarding how ebooks interpret screenplay-formatted text) that required endless troubleshooting. But I’m SOOO excited that I’m finally about to release the book because I truly believe it will be the seminal book on dialogue for the next 50+ years.

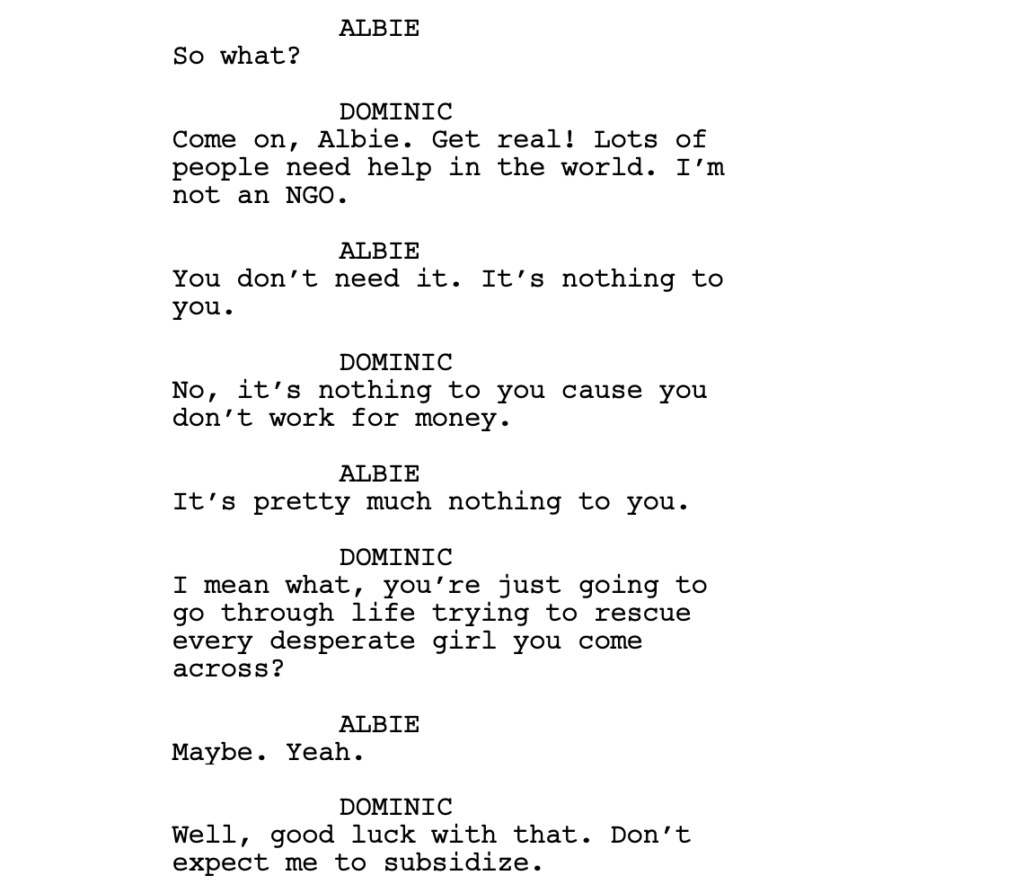

It’s a book with 250 dialogue tips. This in an industry where you’re lucky to find someone who can give you 10 dialogue tips. And I just can’t contain how thrilled I am that I can finally share it with you. I already posted the opening of the book the other week. In today’s post, I’m including a segment from the “Conflict” chapter. This is arguably the most important chapter in the book and it contains 21 tips total.

TIP 121 – Make sure there’s conflict built into the relationship of the two characters who are around each other the most in your movie/show – Who are the two characters who will be around each other the most in your script? You need to build conflict into the DNA of that relationship specifically. That way, almost every scene in your movie is guaranteed to have conflict. John and Jane in Mr. and Mrs. Smith, Tony Stark and Steve Rogers in Civil War, Allie and Noah in The Notebook, Lee and Carter in Rush Hour, Danny and Amy in the Netflix show, “Beef.”

TIP 122 – Using worldviews to create conflict – Okay, but how do you build conflict into the DNA of a relationship? One way is to give characters different worldviews. Have them see the world differently. If you do this, your characters will be at odds with each other for an entire movie as opposed to one or two scenes. In the Avengers movies, Tony Stark’s worldview is he’s willing to get dirty to protect the universe. Steve Rogers’ worldview is governed by honesty. He wants to play by the rules. That difference in their worldviews is why the two butt heads so much.

TIP 123 – Embrace the word “NO” – “No” is the OG conflict word. Without it, most conversations become boring. Let’s say your hero tells his wife, “I’m going to the store,” and she replies, “Okay.” How is that going to result in an interesting conversation? Or your assassin asks his handler, “Is it okay if I skip this assassination? I don’t think it’s safe enough.” And the handler replies, “Sure, no problem.” When people agree with people, the conversation immediately stops. This is why you want to integrate “No” (and all forms of it) into your dialogue. Here’s an example from the HBO show, White Lotus. In it, 23 year old Albie has fallen in love with a local Italian prostitute who owes her pimp money. Albie wants to help pay her pimp off, so he comes to his rich father to ask for money.

TIP 124 – Make them work for their meal – The reason “No” is so great for dialogue is that it forces your character to work for their meal. They don’t get a free pass. The above scene goes on for another three minutes and Albie has to resort to offering something to his father to get the money. That’s what makes the scene entertaining – that he has to work so hard for his meal. And he wouldn’t have had to do it if his dad had said, “Yes.”

The Scriptshadow Dialogue Book will be out within the next two weeks. But there’s a chance it could be out A LOT SOONER. So keep checking the site every day! In the meantime, I do feature script consultations, pilot script consultations, short story consultations, logline consultations. If you’ve written something, I can help you make it better, whether your issues involve dialogue or anything else. Mention this post and I will give you 100 dollars off a feature or pilot set of notes! Carsonreeves1@gmail.com