Search Results for: star wars week

Genre: Sci-Fi

Premise: Stranded on a strange planet, a group of marines must fight off an alien enemy while trying to discover the origin of giant artificially constructed halo orbiting the world.

About: Oh boy does this one have a backstory. The Halo movie was one of the surest things in Hollywood. This thing would’ve broken box office records everywhere. And with Peter Jackson taking point as the producer of the series, you might as well have started opening Halo Banks around the Jackson household that just spat out money. Jackson made a controversial choice to helm the the mega-movie, hiring little-known director (at the time), Neil Blomkamp, but that controversy subsided quickly when people saw his jaw-dropping sci-fi short films (one of which is included below). So as everyone eagerly awaited the next big Halo movie news, they were blindsided when the project was abruptly canceled. Why was it canceled? MONEY, of course. The studios are used to having a lot of leverage in these situations. But this time they were going up against a company bigger than they were, Microsoft. Microsoft just wasn’t going to give up all the profits the studios wanted. So they said, “Fuck you.” And that was that. The film was dead. Which is really too bad. It had a great producer, a great director, and a great writer (Alex Garland). All the pieces were in place. But I guess we’ll never get to see that place. What did we miss? Let’s find out.

Writer: Alex Garland

Details: 2/6/05 draft (127 pages)

I remember playing the first Halo game. It was like nothing I’d ever experienced before on the video game front. My favorite moment was weaving my way through a huge cave, coming out into a valley, and seeing this huge war going on in front of me, with each side lobbing missiles and grenades at each other – the kind of thing you were used to seeing in a cut-scene. I finally realized that it was my job to go INTO that battle. I was about to become a part of it. It all felt so seamless, so realistic, so organic. Video games just hadn’t done that before then. And on top of that, there was this really cool story going on the whole time about this “Halo” thing floating up in the sky. A big reason I kept charging through the levels was to find out more about that giant mysterious object. The combination of that seamless lifelike playability and the great story made Halo one of the best video games I’d ever played.

Naturally, like everyone else, I couldn’t wait for the sequel. And when it finally arrived, I was quietly devastated. Gone was the focus on story, replaced by a focus on multi-player. I’m not going to turn this into a debate about which is better. All I can say is what’s more important to me. Since you guys read this blog, you already know the answer to that. Story story story. I don’t remember anything about the Halo 2 story and checked out afterwards. I never even played Halo 3.

Which brings us to the Halo movie. It’s gotta be one of the most interesting video game adaptation challenges ever. The game itself is inherently cinematic, which should make it an easy base for a film. However, it’s also heavily influenced by past films, particularly Aliens, which essentially makes it a copy of a copy. How do you avoid, then, being derivative? Also, which story do you tell? Do you retell the story of the first game in cinema form? It’s got the best story in the series by far, but don’t you risk the “been there, done that,” reaction? Or do you try to come up with something completely new? And if you do come up with something new, how does that fit into the chronology of the other games? Oh, and how do you base an entire movie around a character who never takes off his mask? That’s going to be a challenge in itself.

I had all of these questions going on in my read in anticipation of reading Halo. Let’s see how they were answered…

The year is 2552. A species of nasty aliens known as The Covenant are waging an all-out war against the human race. A “holy” war they call it. “Holy” code for “turn every single human into red pulp.” In the midst of a large scale space battle, the largest of the human ships, the “Pillar of Autumn” is able to make a light speed jump out of the action.

They arrive outside a unique planet with an even unique(er) moon – A HALO (“You can be my Halo…halo halo!”). This artificial HALO moon thing is fascinating but before the humans can start snapping cell phone pictures of it, the Covenant zips out of lightspeed behind them and starts attacking their ship!

Captain Keyes senses that his ship is about to be shredded into a billion slivers of steel so he wakes up his secret weapon, and our hero, Master Chief. Master Chief is part of a supreme soldier project called the “Spartans” (apparently their creator was a Michigan State fan). He’s insanely tall, insanely strong, and is coated with some super-armor that could probably deflect a nuclear bomb.

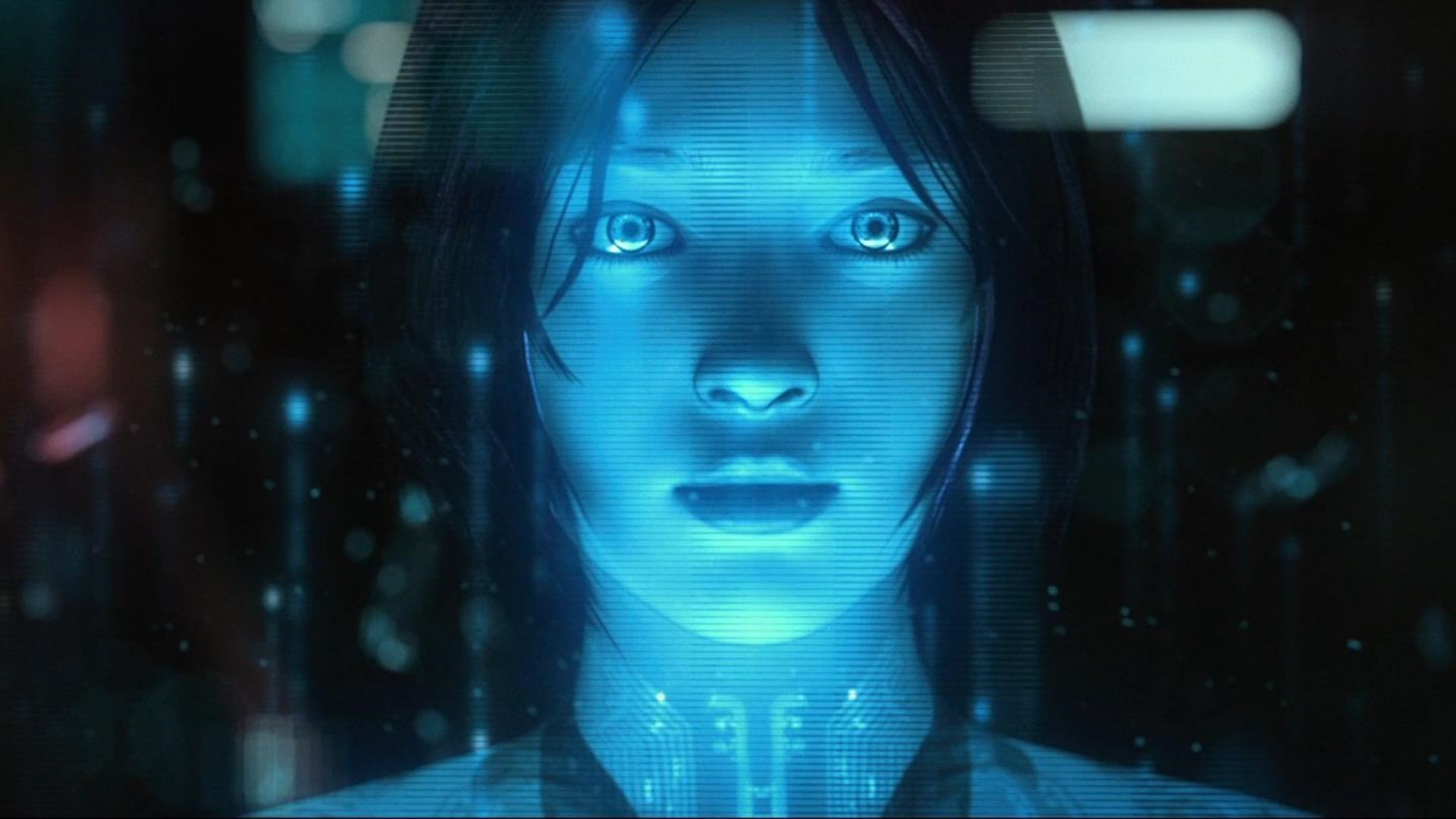

Keyes tells Master Chief he needs him to take the ship’s AI, a witty little female thingy named Cortana, to the safety of the planet below. If the Covenant catch her, they’ll have access to all sorts of revealing stuff, including the location of Earth, which would allow them to deliver their final blow to mankind.

Master Chief obliges because that’s his job, to oblige. So Cortana is wired into Master Chief’s suit and down they head to the planet for safety. Once there, they encounter a couple of problems. The first is that the Covenant are coming down to the planet to blow their asses out of the jungle. The second is that there seems to be some long-since-left-behind alien structures all over the planet, tech that belonged to a previous species much more advanced than both the humans and the Covenant. And this tech looks to have been created for nefarious purposes.

Somehow, they realize, this all ties back to Halo, and it’s looking like the only way they’re going to get out of here AND save the universe from these spooky ancient aliens, is to blow Halo up, something that isn’t going to be easy with the oblivious Covenant trying to kill them at every turn.

Uhhh, does this plot sound familiar to you? That’s because it is! It’s the exact same plot, beat for beat, as the video game. Sigh. Yup, Halo: The Movie was just a direct adaptation of Halo 1. I don’t know if I wasn’t into it because I always knew what was coming next or if the story didn’t translate well, but I often felt impatient and bored while reading Halo. Garland did a solid job visualizing the story for us. But I still felt empty afterwards.

A big part of that had to do with Master Chief. I was worried about him beforehand because in the video game, like a lot of video games, you don’t know much about your hero, mainly because the hero is you! You’re doing all the running around and the jumping and the shooting and the thinking, so regardless of whether the guy has any backstory or not, you feel a deep connection to him because you’re controlling him.

A movie is different though. We need to have some sympathy or empathy for the hero, and a good portion of this is built on your main character’s life, what’s happened to him before he’s reached this point. There’s a recurring dream sequence where Master Chief is on some battlefield and gets saved by a marine that’s SUPPOSED to make us feel something for him, but I’m still unclear as to what that was. His haunting backstory is that someone had to save him on a battlefield? Not exactly the stuff that wins writers Oscars.

But what really hurts Halo is how damn reactive Master Chief is. He doesn’t do anything unless someone tells him to do it. “You have to bring Cortana down to the planet.” “You have to go back up and save Captain Keyes.” “You have to go find the map that will lead us to the Halo Control Room.” Again, that kind of stuff works in a game because IT’S NEEDED. If there wasn’t someone telling us what to do, we wouldn’t know where to move our character. We wouldn’t have any direction.

But in movies (ESPECIALLY action movies), we need a character who’s active, who makes his own decisions. Or at least we usually do. There was this overwhelming sense of passivity in Halo, like we’re being pulled along on a track, at the mercy of a conductor announcing, “We will be arriving at the midpoint in twelve minutes. Midpoint in twellll-ve minutes.” Why can’t we be in the cockpit of a plane, making our decisions on where the hell we want to go?

And so the story quickly brought on this predictable quality to it. Every section was perfectly compartmentalized. Here’s mission 1. Here’s mission 2. Here’s mission 3. There was no freedom to the story like there was in, say, a Star Wars, where something unpredictable would happen every once in awhile (the planet they spent the first 45 minutes preparing to get to is gone upon their arrival!).

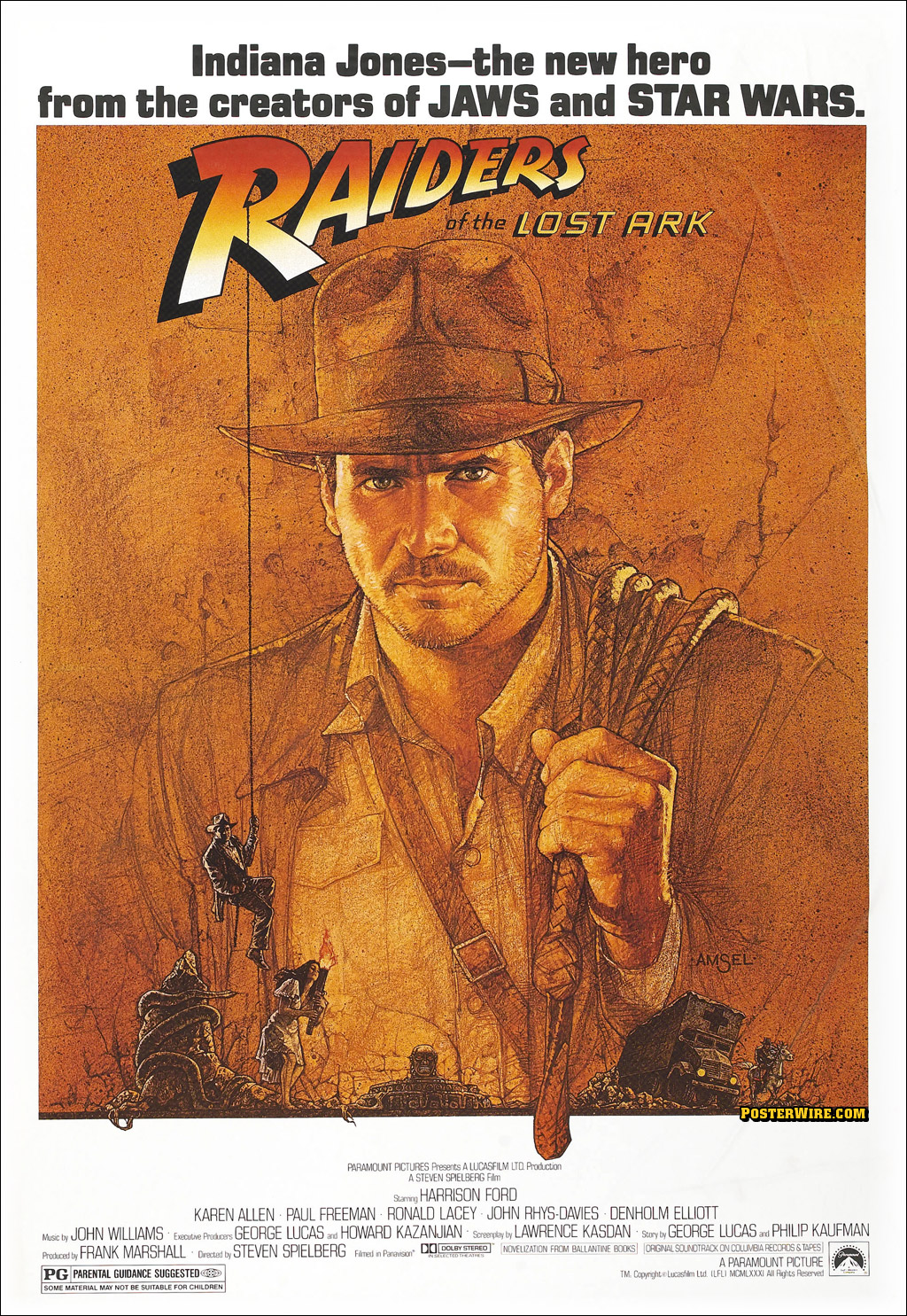

I DID like the idea of adding a MacGuffin here (Cortana) but unlike other movies with strong Macguffins (Star Wars – R2-D2, Raiders – The Ark, Pirates – the gold coin) I never really got the sense that the Covenant wanted Cortana that badly. If everybody isn’t desperately trying to get the MacGuffin, then there’s no point in having one.

But I think whichever incarnation the Halo movie takes (assuming it gets made), they need to focus a lot harder on the character of Master Chief. Really get into who he is and what he is and how he got here and how he’s going to overcome whatever issues he’s dealing with. That stuff matters in movies. There was a hint in the script of Master Chief being this genetic anomaly, a non-human. Why not explore that? This feeling of not fitting in? It’s one of the most identifiable feelings there is and has worked for numerous other sci-fi franchises (Star Trek, X-Men). Not that any of this will affect box office receipts, of course. But if they want to actually make a GOOD MOVIE, something that lives beyond opening weekend and brings new fans to the game itself, more attention to character ain’t going to hurt.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: I think there are three kinds of characters. There’s the active character, the reactive character, and the passive character. The active character is almost always best (i.e. Indiana Jones) since it’ll mean your hero is driving the story. The Reactive character is the second best option (i.e. Master Chief). “Reactive” essentially means your character waits for others to tell them to do something, and then the character does it. I don’t prefer this character type but at least he’s doing things. He’s still pursuing goals and pushing the story forward. The passive character is the worst option. The passive character is usually doing little to nothing. They don’t initiate anything. They don’t react to anything. They’re often letting the world pass them by. The most recent example I can think of for a passive character is probably Noah Baumbach’s “Greenberg” with Ben Stiller. Didn’t see it? Exactly, nobody did. Because who wants to watch a character sit around all day doing nothing?

What’s the easiest way to tell the difference between an amateur and a pro script? That’s easy: CHARACTER DEVELOPMENT. The pros know how to do it. Amateurs don’t. Most amateurs don’t even attempt to add character development. And the ones who do usually use something like addiction or the death of a loved one to add depth. It’s not that you can’t or shouldn’t add these traits. But if you really want to delve into your character and make him/her three-dimensional, you want to give them a flaw, then have them battle that flaw during their journey, only to overcome it in the end. This is called a “transformation,” or an “arc.” It’s when your character starts in a negative place and finishes in a positive place. If you really want to boil it down and get rid of the fancy-schmancy screenwriting terms, it’s called “change.” And the best movies have central characters who go through a big change.

Now I don’t have 50 hours to write about character development so I can’t get too detailed here. But I should tell you a few things before I get to the meat of the article. Character flaws are more prominent in some genres than others. For example, you should ALWAYS include a character flaw in a comedy. Our inability to overcome our flaws is essentially what leads to all the laughs in the genre. Action movies, on the other hand, often have heroes who don’t change. The story moves too fast to explore the characters in a meaningful way. Thrillers are similar in that respect, although a good thriller will find a way to squeeze in a character flaw (I remember that movie “Phone Booth” with Colin Farrel and how it dealt with a selfish character). With horror, it depends on what kind of horror you’re writing. If you’re writing a slasher flick, character flaws aren’t necessary. A thinking-person’s horror film, though? Yeah, you want a flaw (the lead’s flaw in The Orphange was that she coudln’t move on with her life – she was obsessed with the past). In dramas, you definitely want flaws. Westerns as well. Period pieces, usually.

In my own PERSONAL opinion, you can and should ALWAYS give your characters flaws, no matter what the genre. People are just more interesting when they’re battling something internally. Without a flaw, without something holding them back, characters don’t have to struggle to achieve their goal. And that’s boring! Think about it. I always tell you to place obstacles in front of your hero so that it’s difficult for them to achieve their goal. Well what if while your character’s battling all these EXTERNAL obstacles, he also has to battle a huge INTERNAL obstacle?? Much more interesting, right??

You just need to match the kind of flaw and level of intensity of that flaw to the kind of story you’re telling. For example, Raiders is a fun action flick, so we don’t need a big deep flaw for Indy. Hence, Indy’s flaw is his lack of belief in religion and the supernatural. He doesn’t care about the Ark’s supposed “powers,” because he doesn’t believe it has any. But in the end, he finally believes in a higher being, closing his eyes so the spirits from the Ark don’t kill him. It’s a very thin and weak execution of Indy’s flaw, but the story itself is fun and light so it does the job.

The problem I always ran into as a writer was that nobody gave me a toolbox of flaws that I could use. That’s why I wrote today’s article. I wanted to give you eleven (the new “ten”) of the most common character flaws that have worked over time in movies. Now when you read these, you’ll probably say, “Uhh, but that’s too simple.” Yeah, the most popular flaws are simple. And the reason they’re simple is because they’re universal. That’s why audiences find them so moving – they can relate to them. Remember that – the more universal the flaw, the more people you’ll have who can identify with that flaw.

1) FLAW: Puts work in front of family and friends – This is a flaw that tons of people relate to, especially here in the U.S. where our country is set up to make us feel like losers unless we work 60 hours a week. Balancing your personal and professional life is always a challenge. It’s something I personally deal with all the time. I work a ton on this site. And when I’m not working on the site, I’m working on future ideas for the site. That leaves me with very little time to go out and have fun. The question then becomes, over the course of the story, “Will the hero realize that friends and family are more important than work?” We see this explored in movies time and time again. Most recently we saw it in Zero Dark Thirty (in which Maya never overcomes her flaw). Or last year with Billy Beane (Brad Pitt) in Moneyball. Again, it has to match the story you’re telling, but it’s always an interesting flaw to explore.

2) FLAW: Won’t let others in – This is a common flaw that plagues millions of people. They’re scared to let others in. Maybe they’ve been hurt by a past lover. Maybe they’ve lost someone close to them. Maybe they’ve been abandoned. So they’ve closed up shop and put up a wall. The quintessential character who exhibits this trait is Will in Good Will Hunting. Will keeps the world at arm’s length, not letting Skylar in, not letting Sean (his shrink) in, not letting his professor in. The whole movie is about him learning to let down his walls and overcome that fear. We see this in Drive, too, with Ryan Gosling’s character refusing to get close to anyone until he meets this girl. We also see it with George Clooney’s character in Up In The Air.

3) FLAW: Doesn’t believe in one’s self – This should be an identifiable flaw for anyone in the entertainment industry. This business is full of doubters, especially when you’re still looking for a way in. It’s tough to muster up the confidence in one’s self to keep going and keep fighting every day. But this doubt isn’t limited to the entertainment industry. Billions of people lack confidence in themselves. So it’s a very identifiable trait and one of the reasons a main character overcoming it can illicit such a strong emotional reaction from the audience. It makes us think we can finally believe in ourselves and break through as well! We see this in such varied characters as Rocky Balboa, Luke Skywalker, Neo, and King George VI (The King’s Speech).

4) FLAW: Doesn’t stand up for one’s self – This flaw is typically found in comedy scripts and one of the easier flaws to execute. You just put your character in a lot of situations where they could stand up for themselves but don’t. And then in the end, you write a scene where they finally stand up for themselves. The simplicity of the flaw is also what makes it best for comedy, since it’s considered thin for the more serious genres. I also find for the same reason that the flaw works best with secondary characters. We see it with Ed Helms’ character in The Hangover. Cameron in Ferris Bueller’s Day Off (afraid to stand up to his father). And George McFly (Marty’s dad) in Back To The Future.

5) FLAW: Too selfish – This flaw I’m sure goes back to the very first time two homo sapiens met. There’s always been someone who puts themselves in front of others. Everybody in the world has someone like this in their life, so it’s extremely relatable and therefore a fun flaw to explore. It does come with a warning label though. Selfish characters are harder to make likable. Just by their nature, they’re not people you want to pal up with. So you need to look for clever ways to make them endearing for the audience. Jim Carrey in Liar Liar for instance – an extremely selfish character – would do anything for his son. Seeing how much he loves him makes us realize that, deep down, he’s a good guy. But it’s still a tough flaw to pull off. I can’t count the number of scripts readers or producers or agents have rejected because the main character “isn’t likable,” and usually it was because of a selfish asshole main character. A few more notable selfish characters were Han Solo in Star Wars, Bill Murray’s character in Groundhog Day, and Mark Zuckerberg in The Social Network.

6) FLAW: Won’t grow up – This is another comedy-centric flaw that tends to work well in the genre due to the fact that men who refuse to grow up are funny. We see it in Knocked Up. We see it in The 40 Year Old Virgin. We saw it with Jason Bateman’s character in Juno. We even see it on the female side with Lena Dunham’s character in the HBO show, Girls. I’ll admit that this flaw hit a saturation point a couple of years ago, so either you want to find a new spin on it (like Lena did – using a female character) or wait a year or two until it becomes fresh again. But it’s been proven to work because of how relatable a flaw it is. Who isn’t afraid to grow up? Who isn’t afraid of all the responsibilities of being an adult? That’s what I want to get across to you guys. These flaws all work because they’re universal. Everybody has experienced them in some capacity.

7) FLAW: Too uptight, too careful, too anal – You tend to see this flaw in television a lot. There’s always that one character who’s too anal, the kind of person you want to scream at and say, “LET LOOSE FOR ONCE!” We all have friends like this as well, so it’s another extremely relatable flaw. Joel Barish (Jim Carrey) in Eternal Sunshine Of The Spotless Mind is plagued with this flaw. Jennifer Garner’s uptight hopeful mother in Juno is driven by this flaw. And you’ll see this flaw in Romantic Comedies a lot, in order to give contrast to the fun outgoing girl our main character usually meets (Pretty Woman).

8) FLAW: Too Reckless – You’ll usually find this flaw in more testosterone-centered flicks. Like with Jeremy Renner’s character in The Hurt Locker, Martin Riggs (Mel Gibson) in Lethal Weapon, or James T. Kirk in the latest incarnation of Star Trek. The flaw dictates the character enter a lot of big chaotic situations in order to battle his flaw, so it makes sense. I’m not a huge fan of this flaw, though, because I believe the best flaws are universal. That’s why they emotionally manipulate audiences, because people in the audience have experienced those flaws themselves. Recklessness isn’t something people emotionally respond too. That’s not to say it isn’t effective and doesn’t allow for a satisfactory change in an action flick. It just doesn’t hit that emotional note for me like a lot of these other flaws do.

9) FLAW: Lost faith – This is a bit of cheat because questioning or losing one’s faith isn’t necessarily a flaw. But it’s an incredibly relatable experience. Something like 97% of the people on this planet believe in a higher being. But a majority of those people question their faith because now and then something terrible happens to shake it. Which is why you’ll see a ton of characters enduring this “flaw.” We saw it with Father Damian Karras in The Exorcist after his mother dies. We see it with Mel Gibson’s character in Signs after his wife is killed in a car accident. Again, losing someone close to us is a universal experience, so it’s one of those “flaws” that works like a charm when executed well.

10) FLAW: Pessimism/cynicism – This flaw isn’t used as much as the others, but you’ve seen it in movies like Sideways with Miles (Paul Giammati has actually made a living out of this flaw), Terrance Mann ( James Earl Jones) in Field of Dreams, and Edward Norton’s character in Fight Club. I always get nervous around flaws that make characters unlikable and pessimism tends to do that for me. For example, I never warmed to Sideways as much as others because Miles’ pessimism was so grating. But on the flip side, tons of people relate to that character for the very same reason. They’re just as frustrated with life as he is. Which is why the movie has its fans.

11) FLAW: Can’t move on – This is one of the lesser-known flaws but a powerful one. It’s basically about people who can’t move on, who are stuck on someone or something from the past. Their obsession with that past has stilted their growth, and brought their life to a screeching halt. Most famously, you saw this in Up, with Carl Fredricksen, who hasn’t been able to get past his wife’s death. But you may also remember it from the movie Swingers, where Mike (Jon Favreau) is still obsessed with the girl who dumped him. He keeps waiting for that call. With relationships being so fickle, people are experiencing this flaw ALL THE TIME, so it’s very relatable and therefore very powerful when done right.

So there you have it. You’ve now got eleven flaws to start applying to your characters. And remember, those aren’t the only flaws you can use. They’re just the most popular. As long as you start your character in a negative place and explore how they get to a positive place, you’re creating a character with an arc, a transformation. There’s more to character development than this, which I discuss in my book, but getting the character flaw down is probably the most important step. Feel free to offer some of your own character flaw suggestion in the comments section. I’ll be watching closely so I can steal the best ones. :)

For the foreseeable future, every Tuesday will be a Scriptshadow Secrets type breakdown of a great movie, giving you 10-12 screenwriting lessons from some of the best movies of all time. Today will be the first entry, “The Graduate.” Next week will be The Big Lewbowski. And going forward from there, I’ll be taking suggestions. Feel free to offer potential films in the comments section, and if you like what someone’s suggested, make sure to “like” their comment so I know what the most popular requests are.

THE GRADUATE

Logline: A college graduate comes back home, where he’s pursued by one of his mother’s friends, a relationship that is tested when he falls in love with the woman’s daughter.

Writers: Calder Willingham and Buck Henry (based on the novel by Charles Webb)

The Graduate allllllmost made it into my book but, to be honest, I was a little scared of it. The movie is based around the one thing every single screenwriting book tells you not to do – include a passive protagonist. I thought, “What if I can’t figure out why it works? It’ll fly in the face of everything I’ve learned.” The good news is, I DID figure it out. What I realized was that the 3-Act structure is basically built around the idea of an active protagonist. Someone wants something (Act 1), they go after it, encountering obstacles along the way (Act 2), and they either get it or don’t (Act 3). If someone isn’t going after something, the 3 Act structure isn’t as relevant, which is why so many scripts that don’t have a goal-oriented hero fall apart. The solution then, is to offset this lack of action somehow. And you do it with one of the most common tools in the craft: CONFLICT – a central focus of this breakdown. Read on!

1) To quickly convey who your protagonist is, introduce them around people who are the opposite – This is an age-old trick and it never fails. If your hero is crazy, introduce him around a bunch of normal people. If your hero’s too nice, introduce him around a bunch of assholes. The opposing characteristics of these characters will work to highlight your own hero’s traits. So in The Graduate, Benjamin Braddock is introverted and quiet. The writers then THRUST him into his graduation party, where everyone is loud and excited. We wouldn’t have captured Benjamin’s mood nearly as well if all the other characters were just as introverted and quiet as he was.

2) If your hero’s passive, one of the other main characters must be active – If all you have is passive people in your screenplay, then nobody’s going after anything, which means there will be ZERO happening in your script. Someone has to drive the story. In this case, because Ben isn’t active, Mrs. Robinson is. She’s the one who wants Ben, who wants the affair, who pursues Ben. This is why, even though Ben is such a reactive person, stuff is still happening in the story. We have someone pursuing a strong goal.

3) The Power Of Conflict – I realized that the main reason this story works despite its main character being so passive, is that every single scene is STUFFED with conflict. Every scene in The Graduate has either a) two characters who want completely different things, or b) One character keeping/hiding important information from another character. There is just so much resistance in The Graduate. Since each individual scene is so good (due to the intense amount of conflict), it distracts us from the fact that there’s no goal driving the story forward (until later, when Ben falls for Elaine).

4) Easiest Scene to Write – One of the easiest ways to make a scene fun is to give one character a SUPER STRONG GOAL and give another character the EXACT OPPOSITE GOAL. This creates conflict in its most potent form, which leads to a high level of drama. It’s no coincidence that this approach created one of the best scenes of all time, Mrs. Robinson trying to keep Ben at the house and seduce him (her goal) while Ben is trying desperately to escape and avoid her seduction (his goal).

5) STAKES ALERT – Notice how when Mr. Robinson invites Ben to a nightcap, he says, “How long have your dad and I been partners?” This is a HUGE piece of information as it raises the stakes in Ben and Mrs. Robinson’s relationship considerably. If the only thing at stake in this affair is Ben’s pride or emotions, that wouldn’t be enough to drive an entire movie. But screwing up his father’s business, that’s a whole different ballgame. You want to make sure the consequences for your characters’ actions are as big as they can possibly be.

6) MID-POINT SHIFT ALERT – The Graduate has one of the best mid-point shifts I’ve ever seen. Elaine, Mrs. Robinson’s daughter, comes back from school. She and Ben are then set up. The whole second half of the movie now moves to Ben’s relationship with Elaine while he tries to fend off a scorned Mrs. Robinson. Like all good mid-point shifts, it adds a new wrinkle to the story that keeps it fresh. Had they stretched Ben’s relationship with Mrs. Robinson across the entire story all on its own, the movie likely would’ve run out of steam.

7) Cheating/Infidelity scripts must be PACKED with dramatic irony – When you have a character cheating or a couple hiding a relationship from others, you want to put them in as many situations as possible where there’s dramatic irony. For example, when Ben first meets Elaine before their date, Mrs. Robinson is in the room, leering at them from the corner. Same with an early scene where Mr. Robinson invites Ben for a nightcap and Mrs. Robinson (who just tried to seduce Ben moments ago) enters the room. We feel the tension because of the secrets Ben and Mrs. R share. These situations also lead to some great line opportunities, such as when Mr. Robinson says to his wife, “Doesn’t he look like he has to beat the girls off with a stick?” “Yes,” she replies. He does.

8) The “Bad Date” Scene – The Graduate did something really cool that I’ve never noticed before. The story needed to show Ben and Elaine fall in love quickly because Elaine had to go back to college and we had to believe Ben had fallen in love with her enough to chase her there. Normally, I see writers writing these “lovey-dovey” scenes to prove their leads’ love to the audience (see Star Wars Episode II: Attack Of The Clones). For whatever reason, these scenes often have the opposite effect, making us nauseous and annoyed by the couple. So The Graduate takes the COMPLETE OPPOSITE approach. Ben’s only going on a date with Elaine because his parents make him. In order not to piss off Mrs. Robinson, he’s a total bitch to Elaine all night, taking her to a strip club and embarrassing her on stage. It gets so bad that Elaine starts crying, making Ben realize how much of a jerk he’s been. He apologizes, which leads to their first kiss. Experiencing a traumatic night instead of an ideal one thrust them much deeper into their relationship, adding the kind of weight to their experience a “happy” date just wouldn’t have been able to achieve. So the next time you write a first-date scene or need to accelerate a relationship, consider your characters NOT getting along instead of getting along.

9) SCENE AGITATOR ALERT – Remember, you should always look for ways to make it difficult on your hero in a scene, especially when they want something badly. So when Ben finally gets to Elaine’s college and spots her getting on a bus, he follows her on in an attempt to win her back. Except Ben isn’t able to sit next to Elaine because someone’s already sitting there. He’s forced, instead, to sit diagonally behind her, meaning he has to lean forward at a weird angle to make his case. It’s awkward. It makes his task difficult. And that’s exactly what you want to do to your character. If it’s too easy, you probably aren’t getting enough drama out of the situation.

10) “Crash the Party” moment – Whenever something’s going too good for too long for your protagonist, “crash the party.” In other words, bring them back down to earth. So later in the movie, after Ben’s chased Elaine to her college and the two have spent multiple scenes having the time of their lives together, Ben arrives back at his hotel to find Mr. Robinson waiting for him. He crashes the party, informing Ben that he knows about the affair, and that there’s no way he’s letting Ben anywhere near his family from this point forward.

These are 10 tips from the movie “The Graduate.” To get 500 more tips from movies as varied as “Inception,” “When Harry Met Sally,” and “The 40 Year Old Virgin,” check out my book, Scriptshadow Secrets, on Amazon!

Black List? Hah. Hit List. Nope. My top 10 screenplays of the year!

For those of you disappointed that the end of the world didn’t come, I say to you, chin up! A new year is upon us, which means new possibilities, new frontiers, new chances to sell your script. For a little inspiration, let’s look back at the best scripts of the year. Or, at least, the best scripts of the year in my opinion. Which is, of course, the only opinion that matters. For those of you unfamiliar with my end of the year “Best Scripts” list, they don’t always fall in line with my Top 25. I know that makes zero sense, but some scripts burrow into your soul and stay with you all year while others burn brightly at first but fade faster. Still, you’re going to see a lot of familiar faces here, and a couple of surprises. The scripts on this year’s list have a few things in common. They’re either shocking, consistently surprising, really well-written, have a unique voice, have amazing characters, or all of the above. Wanna take a look? So do I!

10. Promised Land – Promised Land is about as “plain” a script as you can get away with and still have it be great. We’ve got a small town. We’ve got small characters. For a script like this to work, the writing has to be top-notch, and it is. I think what stayed with me the most was how much pressure was put on the main character. That pressure created high stakes, which made us care about whether our hero was going to succeed or not. This is something I felt a script like Lincoln really failed at. Despite the 13th Amendment being one of the most important moments in history, the writer managed to make Lincoln’s plight feel only a fraction as important as Promised Land (yes, I just used Promised Land to take one more shot at Lincoln). Anybody seen this movie yet? How is it?

9. Untitled Arizona Project – Rarely does a script with just one great scene leave such an impression on me, but this one did. Yes, I’m talking about the Squirrel Scene. For those unaware of the Squirrel Scene, just imagine being trapped in a confined space and then being bombarded with hundreds of terrified angry squirrels. Yes, that actually happens in this script. But this is also one of the unique voices I was talking about. You’re so unsure of what these bizarre one-of-a-kind characters are going to do next, you can’t help but continue reading. I remember reading this one like it was yesterday, which I can only say for a handful of scripts.

8. Echo Station – Is Echo Station benefitting from the freshness of only being read a week ago? Probably. But I always admire a time-jumping or time-looping narrative that stands up to plot scrutiny. Usually these scripts fall apart faster than a flan baked by your Cousin Edna. Can it handle scrutiny by the super time-travel script assassinators? Probably not. But I’m not sure any time-travel movie can. I mean, those guys could find fault in Back To The Future. I also think Echo Station is a great reminder of what kind of spec gets noticed in the industry. A little hook, a lot of urgency, and some high stakes.

7. The Disciple Program – The Disciple Program is a little like Star Wars at this point. I’m not sure I can say anything new about it. So I’ll just remind you of how the script was written, which continues to fascinate me. TDP was written 10 pages at a time for a contest. Each of those 10 pages was vetted by a judge and those notes sent back to Tyler. So every time Tyler had to turn something in, those self-contained 10 pages had to be exciting and memorable in some way. This is why the script stays consistently good, because you know every ten pages something interesting is going to happen. Now is this a surefire way to success? No. I’ve read some of the other scripts that were in the competition and they didn’t light the world on fire. But it’s still a solid technique that every screenwriter should try at least once.

6. Origin Of A Species – For those who don’t remember, this is the script that won Amazon’s Screenwriting Contest. I’m still kind of surprised by how much flak that contest got. They gave out gobs of money to screenwriters, more than any other competition by far, allowing many of those writers to obtain some momentary financial freedom so they could continue their dream, and they did it over and over and over again. And they also found this script, which was a really original voice and a story so far removed from conventional structure that I needed Google Maps to get me back on track. This writer has a hell of a talent for making small moments interesting. He’s also great with dark moody material. I haven’t stopped thinking about this one.

5. Saving Mr. Banks – To me, the scripts that really give me hope are the ones that I have no business liking, and yet somehow they win me over. I’ll tell you why: Because it reminds me that the most important aspect of your screenplay is your characters. Characters can exist in any world, whether it be space, football, lumberjacking, or children’s book authoring. If they’re interesting enough, if they’re relatable and compelling enough, we’ll wanna see what happens next. There was no reason I should’ve loved a script about a bitchy middle-aged woman complaining about her children’s book being made into a movie. It’s a testament to the writing that I did.

4. The Ends Of The Earth – Myself and the word “sweeping” don’t generally hang out at the same coffee houses. “Sweeping” is something I’d expect from a romance novel. Which is ironic, I guess, since “Ends Of The Earth” is a love story. Although it’s nothing like the love stories you grew up on. This ain’t no Nicholas Sparks, that’s for sure. I won’t spoil the big hook since, if you ever read the script, it’s best to go in knowing nothing. I’ll just say that, despite its defiance of my coveted GSU, it again goes to show that if you have two compelling characters at the heart of your story, you can get away with a lot of structural defiance.

3. The Equalizer (no review) – Here’s the thing. Every star is looking for a franchise. Everyone wants their Bourne, their Mission Impossible, their Die Hard. Because successful franchises mean longevity. If your career ever goes south (and it can happen folks – remember when Val Kilmer was an A-list actor?), you can pull out another episode from your franchise and you’re back in the mix. It’s why Cruise grabbed onto the Jack Reacher books. It’s why Wahlberg attached himself to Disciple. But franchises can’t become franchises unless that first movie kicks ass. And man is this movie going to kick ass. People have complained about the fact that Denzel’s character never once seems to be in danger. And usually that kind of thing bothers me. But there’s something about how this guy is built that you can’t wait to see him beat down the bad guys. He’s almost like a superhero. You know he’s going to win, you know they don’t have the skills to beat him, but you don’t care. — Equalizer also has the distinction of being the best SCRIPT I’ve read all year. What I mean by that is the writing is so crisp and clean and descriptive and to-the-point. It consistently conveys a ton of information in very few words, which is the essence of good screenwriting.

2. Django Unchained – Quentin is the master of scene-construction. Each of his scenes is like a mini-movie with a set-up, an implied collision, and a climax. I don’t know how anyone writes a 160 page screenplay and has me riveted on every single page. If not for that late scene (spoiler) where Django artificially cons his captors into letting him go – the only point in the script where I was aware of the author’s pen – this probably would’ve been my number 1. But other than that – awesome! I mean what a unique fucking story. A German recruits a black slave to become his apprentice in hunting down slave owners? Genius! And in classic Tarantino fashion, you’re never quite sure what’s going to happen next.

1. Desperate Hours – Third act. Third act. Third act. Leave them riveted as they close the final page and they’ll go racing to tell everyone they know about your script. The third act of Desperate Hours is absolutely un-freaking-believable. I don’t know if I’ve ever read a script where I’ve agreed with every single choice the writer made, but I did here. There is so much skill on display in “Desperate,” so much mastery of craft and structure, you’re going to need a scalpel to scrape it all out. The two big knocks on the script were a lack of memorable dialogue and a slow opening. For whatever reason, neither of these bothered me. I usually like realistic dialogue as opposed to the fancy memorable stuff, which is probably why the absence of flash didn’t occur to me. And I was curious enough about the main character that the first act moved quickly (I was intrigued to learn how he had gotten to this point!). I just loved this script. It’s wrapped up in Johnny Depp Land at the moment. Here’s hoping Depp doesn’t wait another 15 years to make it, but rather offers the lead role to another actor.

That’s it for me folks. Doesn’t look like there’s going to be a post tomorrow due to it being New Year’s and all. I’m not a huge partier but even I have to have a little fun every once in awhile. This should give this post plenty of time, however, to get all of your Top Tens in. I’d love to hear about some scripts I haven’t read yet. HAPPY NEW YEAR! (note – I still haven’t transferred the comments over from the old site so sorry there are no comments on these older posts).

Genre: Comedy

Premise: When four grown-up siblings come back to visit their parents on their 35th anniversary, they’re greeted with a devastating family secret that changes everything they know.

About: This script leapt up and grabbed onto the 2007 Black List with its fingernails, refusing to let go.

Writer: Peter Craig

Details: 109 pages, March 23rd, 2007 revisions

My new thing is using one review slot a week to dig up an old script from 4-10 years ago, and review it. The hope is to find something everyone forgot about. There are times where a couple of big specs hit and the waves they generate are so high that all the little guys get swept away. And maybe those little guys wrote something good. I’ve seen my share of strong scripts that were either passed over or entered development hell immediately, so I’d like to be the lighthouse that guides those scripts back to shore.

The question is, how clueless do I want to be in choosing these scripts? Do I not want to know ANYTHING other than the title and that they finished on the Black List? Apparently, that’s the call I made this week, and booyyyyyyy do I regret it. Okay so look. We all have off days. We all pick up or write a bad script every once in awhile. But does it have to be a back-from-the-dead-hopefully-this-will-be-awesome Scriptshadow review script? Humph.

Today’s script falls into that love-it-or-hate-it subgenre known as the “Wacky Family Independent Film.” Oh man! Those family members. They’re all so wacky! This was popularized by Wes Anderson and somewhere between the years of 2002-2005, everybody and their crazy grandpa was writing one of these. I think I wrote one too. And it was dreadful. So I feel you, Peter. But there was a success or two. Little Miss Sunshine did well, right? I mean, its writer is now writing the next Star Wars movie. But then you had your Running With Scissors’es…es. And those were just as unpleasant as the Sunshine’s were pleasant. Even Wes Anderson seemed to get bored of the genre he popularized, pumping out pale imitations of his earlier films.

Which I guess leads us to Relativity, which I’m relatively sure isn’t going to get a lot of feedback here on Scriptshadow. In fact, I’m willing to bet the comments will dive to subatomic levels, which is probably a good lesson for screenwriters out there. The comments section on Scriptshadow is pretty a pretty good indicator of the public’s general interest for a film. If an idea or genre is boring, people aren’t going to see it (or comment on it).

So with that said, let’s start butchering—er, I mean reviewing. I’ll try to be clean and kind. I’ll try to make this painless. Then I’ll broil the meat instead of fry it so we can have a healthy Monday Scriptshadow meal. Waddaya say?

50-somethings Claire and Franklin Fergusson should be at the precipice of a wonderful weekend. They’re about to celebrate their 35th anniversary with all four of their excitable grown-up children, who are coming home to joyously participate in the festivities.

Except Claire and Franklin have been hiding a deep secret from their children. All four of them were adopted! So when unkempt Charles, nervous twin Vincent, uptight Conrad, and artsy Judith, show up and hear the news, they’re…hmmm, well, upset to put it mildly. The biggest issue seems to be that all of them thought they were born into a rich prestigous family, when in fact they were all poor and deserted by their families.

Vincent is so confused by the news that he runs away. Charles becomes manically obsessed with the fact that Vincent isn’t his real twin and decides to celebrate his “individual” birthday as a sort of “fuck you” to the news. Judith learns she was the daughter of a Russian spy and a hooker and doesn’t know what to do with herself. And I’m not sure what happened to Conrad. He got shafted as far as storylines go because I can’t remember a single thing about him.

As far as the plot, that’s pretty much it. Our four 30-something adopted grown-ups just sort of run around and pout. There’s no goal. No real story. It’s just people complaining to each other. I’m not going to say it’s all bad. I did giggle a couple of times. And if you’re into this kind of humor, you’ll find it funnier than I did and that might help cover up some of the script’s other problems. But that’s the thing. Relativity had so many problems that they couldn’t possibly all be covered up.

So let’s pretend we live in an alternate reality where I’ve been asked to guide this script through development. I would start by adding an actual story. Currently, these kids come home to a 35th anniversary that nobody cares about, that has no festivities or schedule, and that has no stakes attached to it whatsoever. Why would you make that the story center? It’s boring! Make it a wedding instead. Probably Vincent’s, since he brings his fiancé home anyway. Now we have more of a ticking time bomb. We have something that can be interrupted and ruined, which means the stakes will be higher.

Then, instead of this adoption information being offered up voluntarily, which feels beyond artificial (there’s no reason for the parents to bring this up now other than that the writer wants to so he can have a story), the information should come out by accident. One of the kids stumbles upon it at the house. Or another finds a semi-clue and puts two and two together. The kids confront their parents. The parents admit it. Now the situation feels a little more believable.

And here’s a question: Why do the kids have to find out all at the same time? It might be more interesting to have the news spread from kid to kid gradually. That could be fun, with Vincent being the one person the others know CANNOT FIND OUT HE’S ADOPTED. They know he’ll have a mental breakdown. And they know it will destroy the wedding. So everyone’s trying to keep the secret, but at a certain point, too many people find out, and then right before the wedding, Vincent finds out, and everything goes to hell.

I’m afraid that particular story improvement would only slow the bleeding though. This script has too many issues. My biggest problem was that there wasn’t a single authentic moment in the entire screenplay. Nobody acts logically. Choices are made for cheap laughs rather than exhibiting what the characters would really say or do in these situations. For example, one of the kids points out that they SAW the mom pregnant when they were young – which means at least one of the kids can’t be adopted. The mom counters that they suspected the kids might possibly remember an adoption, so to trick them, she stuffed her dresses with pillows to give the appearance that she was pregnant.

Oh. M. Gee.

Seriously???

I mean, come on.

Okay, look. I get that this is supposed to be broad. It’s wacky. It’s nonsensical. And that’s supposed to be the funny part of it. But there wasn’t one REAL moment in the entire script. And because nobody acted real or authentic, I didn’t care about them. Even in Wes Anderson films, like Rushmore, the characters have hearts and feelings. This felt like 7 Jim Carrey’s running around trying to out-overact each other.

Relativity also severely handicapped itself by making its main characters a bunch of rich snobs. These are by far the hardest characters to make likable. There are exceptions where rich people can be made sympathetic (actually, anybody can be made sympathetic by a skilled writer), but no effort was made to do so here, and as a result, everyone came off as stuck-up, ungrateful, juvenile or annoying.

Then you had the Quirk Factor Level 17. Everything was done specifically to try and be quirky. And I’m not going to get carried away with this. I’ve been there. I’ve written the same kind of characters and the same kind of situations. I think every writer goes through that phase. But when the family members were driving around in a bumper car that was decked out to look like a race car, or the grandfather announced that he had breast cancer (yes, the grandfather)…I just died a little inside. I couldn’t take it anymore.

These kinds of scripts are too artificial for me. I need something to be grounded in reality or to know Wes Anderson’s going to make it all alright on screen. This was way too wacky for my taste. I was thinking about giving it a “What the hell did I just read” but then I realized it wasn’t badly written. It was just not my thing. Hence, it wasn’t for me.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: When doing a character piece, particularly a companion piece, don’t leave your characters out to dry by not giving them a plot, as was done here. Since the 35th anniversary carried no weight and didn’t mean anything to anyone, there was nothing that needed to be done, and therefore nothing for anybody to do. That forced the characters to try and keep the story interesting via their wackiness alone, which they weren’t able to do. Instead, give your characters a looming goal or end game that carries with it HIGH STAKES. Something like a wedding would’ve worked great here. Now characters have things to get done (preparing, planning, creating) which makes all of them more active and more interesting. With an end game, you also give the audience something to look forward to. They’ll want to know if Vincent finds out about being adopted or not. And if he does, what is he going to do?? Look at Little Miss Sunshine. They had to get to the pageant. So they all had a directive, a goal, stakes. You give yourself a way better chance to write a good story going this route.