Search Results for: star wars week

So earlier this month I was reading a screenplay and about 30 pages in I just stopped and thought, “I’m bored.” The script itself had quite a few of elements that I preach on the site – a clear goal, high stakes, urgency. But something wasn’t registering. So I decided to take a harder look at that feeling – boredom – since, as a writer, it’s the worst crime you can commit. But what causes it? Is it some invisible force that one has no control over? Or can it be systematically shut out via a carefully designed approach? That’s the question I set out to answer. And as I looked back at the recent scripts I was bored by, I came to a hard truth. The most influential factor in a reader being bored is something that the writer has no control over – subject matter. If somebody hates baseball, you’re probably not going to win them over with your baseball script. On the flip side, if somebody loves slasher movies, you probably have a good shot at entertaining them with yours. However, assuming all else is equal, these are things you absolutely CAN NOT DO in your script, as they almost always lead to a reader being bored out of their mind.

1) Take forever to set up your story – This is just a killer. The writer is using 4-5 scenes to set up their hero when they could’ve done it in two. It takes them 30 pages to get to the inciting incident. The story doesn’t seem to be pushing towards anything – setting anything up. That’s when you know you’ve failed, when you’ve bored your reader before you’ve even hit the main storyline. So set up your story quickly. Move things along faster than you think you have to. Avoid slow burns unless you have a LOT of experience writing and know how to build a story slowly while keeping the audience’s interest.

2) A passive main character – If your main character is spending the majority of the script waiting for things to happen instead of going out there and pushing the story forward himself, it’s easy for us to lose interest in that character and, by association, their story. Whether it’s the guys in The Hangover actively trying to find out where their friend is, Jake Sully actively trying to infiltrate the Na’vi, Edward Asner (Up) trying to make it to South America to keep a promise to his wife, or Colter looking for the bomb in the train in Source Code, readers like characters who go after things (are ACTIVE). Those tend to be the most exciting scripts. Now there are great movies where the main character is reactive. The Hand That Rocks The Cradle is a good example. Our main character isn’t really doing anything. However a lot of things are happening to her, which keeps the movie entertaining. But if you don’t have a scenario like “Cradle” where there’s a lot of conflict and danger affecting your main character, then you probably want your hero to be active.

3) Boring writing – We are taught as screenwriters to give the reader exactly what they need in order to understand the story and nothing more. And that’s good advice. Nobody wants to read six line paragraphs dominated by pretentious thesaurus-laden prose. But if you take that advice too literally, you risk becoming too sparse and boring with your writing. Then by association, WE get bored. An analogy might be a guy telling a story at a party. If that guy’s staring at his shoes and mumbling the whole time, it doesn’t matter how great his story is, it’s going to be boring. But if he’s excited and into it and vocal and looking everybody in the eye, that story’s going to have life. So the trick is, within the confines of a minimalist style, adding flavor and atmosphere to your writing. “Joe walks over to Mandy and looks at her with a mean stare and then walks away, ” is robotic. “Joe charges towards Mandy, rage emanating from every pore. They come face-to-face. Silence. So much unspoken here. He finally shakes his head and pushes past her.” Not Oscar worthy but definitely more visual.

4) Unexciting subject matter or concept – There are certain stories that inherently lack drama or entertainment value. It is your job to avoid telling these stories. I’m talking about spiritual journeys, plot-less stories, characters in a house discussing life. I’m not saying it’s impossible to make these movies work, but it’s the difference between having the Yankees payroll and the Oakland A’s payroll. Theoretically, the Oakland A’s could win the World Series. But with 200 million dollars more, you’re going to have a much better shot with the Yankees. A movie about a mother taking care of her son lacks drama and entertainment value. A movie about an unstable fan who’s imprisoned her favorite author in an isolated house in the mountains (Misery) is an idea jam-packed with drama and entertainment value.

5) Thin characters – You’ve heard this so many times it probably makes your head hurt. But this is probably the most misidentified reason for people being bored while reading a screenplay. That’s because when someone is bored, they tend to look at the immediate issue. This scene is empty. This dialogue is stale. But the reality is, it has nothing to do with either the scene or the dialogue. It has to do with the characters, who were never developed into interesting people in the first place. You’ve given us no reason to sympathize with them. No clear goal they’re going after. They’re not battling any internal conflict or flaw. They don’t have any interesting relationships in their life that need resolving. Their backstory is nonexistent. Everything about them is empty. Once you’ve made that mistake, it doesn’t matter how good your story is. We won’t care because your thin characters have sent us into a near-vegetative state. So get your character development on. Or else you’ll end up in Boringsville.

6) Scenes that don’t push the story forward. – The more scenes I read that seemingly have nothing to do with your story, the more bored I get. This is why I tell you to have a clear goal for your main character at all times. If you have a clear goal for your hero, then you always know what scenes are necessary and what scenes aren’t. If your character has to deliver a droid to Princess Leia’s father for instance, he’s going to need a way off the planet. So obviously, he’ll need to go to a cantina where a lot of pilots hang out. If your scene isn’t *in some way* pushing towards whatever the current goal for your character is, then it isn’t necessary.

7) Obvious choices – As readers, we read all day. That’s what we do. We read scripts. By the time you finish your script, we’ve probably read 30 to 50 scripts just like yours. That’s your audience – people who read variations of the same thing over and over again. So if all you’re doing is making obvious choices with your scenes, your characters, your plot, your twists, then we’re going to get bored with your story quickly. Your job as a writer is to assess every one of the major choices you make in your screenplay and ask the question, have I seen this before? If you have, consider altering it and making it something that you haven’t seen before. You’re not going to be able to eliminate every cliché in your story. And quite frankly, you don’t want to (we need some sense of status quo to latch onto). But the idea is to constantly push yourself to come up with enough different ideas or spins on old ideas that your script feels fresh.

8) Generic action scenes (especially if they’re endlessly strung together) – This is a common amateur gaffe. Amateur writers tend to mistake “keeping the story moving” for “keeping everything fast.” So they throw action scene after action scene at you, believing that it’s going to keep you interested. But here’s a little secret you should know: The majority of action scenes are actually pretty boring on the page. There aren’t too many ways you can write a car chase or a gun battle that we haven’t seen before. For that reason, all of the bullets and the race scenes and the battling and the fights eventually become one giant blob of generic action. I actually skim through a lot of action sequences because of how predictable they are. What you begin to learn as you get better is that the best action scenes are carefully set up ahead of time. The stakes have been established. The motivations are clear. The dynamics between the characters have been carefully planned out. That way, when we reach the action scene, it’s not so much about the action itself as it is you caring about what’s going to happen to the characters inside of that action. So it’s essential that you’ve set up everything ahead of the action scene instead of focusing on how cool you can make the action scene itself.

9) Lack of clear motivation -This is a huge one. There is nothing more frustrating than losing track of what the hero is trying to do. This happens a lot in plot-heavy stories, since the hero is constantly jumping from new situation to new situation. The second we lose track of what the hero’s role is in these situations – what their objective is – we’re no longer participating in the story. We’re simply trying to figure out what’s going on. And if we’re trying to figure out what’s going on for too long, boredom sets in. So your job is to include “checkup” moments, lines or scenes that remind the audience what we’re doing and why. Imagine, for example, the final Death Star sequence in Star Wars without the “mission breakdown” scene beforehand. X wing fighters would be flying all over the place with us cluelessly wondering what the hell the point of it all was. This is why you get so bored watching sloppily-written movies like Transformers 3 and Pirates Of The Carribean 8. You rarely know what the characters are going after or what they’re doing in a battle. Since we don’t understand what the character’s motivation is, we simply don’t care what’s happening, and that leads to boredom. But this extends far beyond action scenes. I can go through 50 pages and a dozen scenes sometimes where I’m not clear what the hero’s motivation is. That’s when a script becomes really boring.

10) Zero surprises/reversals/twists – Never forget the power of the unexpected. Audiences have grown up on TV and movies. They know every trick in the book. So if your story is too predictable for too long, the audience starts to get ahead of you. And if the audience is ahead of you too frequently, they’re probably bored (except for the use of dramatic irony which I won’t get into here because I don’t want to confuse anyone). So your job as a writer is every 15 to 30 pages, depending on the type of story you’re telling, to throw something in there that that we aren’t expecting. Maybe it’s a character dying who we never thought would die. Such as Colter in the first 10 minutes of Source Code. Maybe it’s the introduction of a new dangerous character, like Mila Kunis’ character in Black Swan. Maybe it’s an action from a character that we weren’t expecting, such as the babysitter in Crazy Stupid Love taking naked pictures of herself to send to Steve Carrel’s character. It doesn’t have to be some mind boggling nuclear-level surprise every time out. But you do have to throw things in there every now and then that the audience isn’t expecting in order to keep them honest. If you don’t, they’re going to get way ahead of you, and once they’re ahead of you, the boredom sets in.

So now what you need to do is go back to your latest screenplay and assess if you’re making any of these mistakes, because if you are, you’re boring the reader, and as we’ve established, that’s the worst possible thing you can do as a writer. I’d also love to hear what you bores you guys when you read scripts. Feel free to vent in the comments. :)

So here’s the scenario. You’ve just been told you’re going to die from cancer in six months. As you sit down and consider what’s most important (family, friends, etc.) you realize that the one thing you want to do before you leave this earth is sell a screenplay. That’s been your dream. If you can pull that off, you’ll die a happy man/woman. But where do you begin? If it was easy, you would’ve done it by now, right? Well, amazing things can happen when you have a literal ticking time bomb lighting a fire under your ass. The main reason you haven’t sold a script yet is because you haven’t maximized your chances. You haven’t skewed all the odds in your favor. Remember, all you want to do is sell a script. It’s not about “art.” It’s not about “staying true to yourself.” You just want to sell a script. With that in mind, I’m going to lay out the most likely plan for achieving this goal. In other words, this is what I would do if I were you.

6 months equals 24 weeks (roughly). Let’s break those weeks down.

WEEKS 1-4 – Come up with idea, maximize story potential, outline.

1) THE IDEA – Here is the most important choice you will make in this entire process because it’s going to MAXIMIZE YOUR READS later on. The more reads you get, the better chance you’ll have of selling your script. You need to come up with a high concept easy to understand idea that you can see 13-25 year olds racing out to the theater to see – Think big. Aliens. Time-travel. Gladiators. Car racing. Dream heists. Dinosaurs. Super-heroes. The apocalypse. Killers with masks. Big ironic comedy situations. Mythical creatures. Ghosts. Monsters. Nazis. Lower budgeted versions of these ideas will give you more potential buyers, but if you’ve got a really great high concept idea, don’t worry about the budget. — Now there are some things I want to mention here. Make sure you’re INTERESTED in the subject matter. If you’re a vampire fan, don’t write about aliens. Write about vampires. Even if we’re just writing this to sell, your love for the subject matter must come through on the page. People can smell a cash grab, which may be what this is. But if you love your cash grab idea, it’s going to read a lot better than if you don’t. Next, the idea has to be clever or unique in some way. It can’t be “Aliens land on earth and start destroying things.” We’ve seen that before. “The Days Before,” a spec that sold a couple of years ago, had aliens jumping back in time a day at a time to destroy earth. It was different. Your idea has to be different. Finally, TEST DRIVE YOUR IDEA. This will be one of the most IMPORTANT STEPS YOU’LL MAKE IN SELLING YOUR SCRIPT! Mix up your idea with ten others (find other loglines from Scriptshadow or Tracking Boards) and have your friends rank them. If your idea doesn’t consistently finish near the top, don’t write the script. Come up with another batch and start over again. I know time is ticking but I can’t stress how important this part of the process is for later.

2) CLEAR STORY – I would make sure that this is a clear easy-to-understand story. A hero with a CLEAR GOAL he DESPERATELY WANTS TO ACHIEVE. Indiana Jones going after the Ark. Marty McFly trying to get back to the future. Colter trying to find the terrorist in Source Code. Note that this doesn’t mean “dumb your story down.” I don’t think anyone would call Raiders or Back To The Future “dumbed down.” It just means not having 7 different subplots winding around a murky narrative. Hero desperately trying to achieve something and shit gets in his way. That’s the structure you want you to go with.

3) MAIN CHARACTER – I would have an interesting male main character. Remember, a big actor has to want to play the lead role. That means the role should be juicy and in the 28-45 age range. Have some conflict going on inside of them. Neo doesn’t believe in himself. Denzel in The Book Of Eli (a big spec sale from a first timer) is afraid to get close to others. Make sure there’s something – it doesn’t have to be game-changing – but SOMETHING the main character is battling. Because one of the first questions the producers will ask is, “Who can I cast in this role?”

4) KEEP IT EXCITING – Make sure something interesting and/or unexpected happens every 15 pages or so. 110 pages is a lot of white space and watching one character try to do the same thing for 2 straight hours is boring. So unexpected things need to happen along the way to mix it up. Have your main character die (Source Code), get caught by the Germans (Indiana Jones) or get to his destination only to realize it’s no longer there (Star Wars). If something interesting or unexpected or surprising or stake-raising doesn’t happen every 15 pages or so, your script is probably getting boring.

5) OUTLINE – Outlining saves you rewrite time later. All of the things I listed above (clear goal, interesting main character, something happens every 15 pages), you’ll only be able to do because you’ve outlined. Get yourself a good 3-10 pages to work with and make sure all the major story beats are covered. It’s okay if you don’t have all the details figured out. As long as you know where you’re heading, you’ll be fine. No outline and no direction will equal a wandering storyline. We can’t afford that if we’re going to sell this puppy.

Weeks 5-10 – Write The Script

6) WRITE – I would write at least 8 hours a day. But because you’re dying, you should probably write even more. Also, because you’re dying, you’re not allowed those excuses you usually use. “Oh, I’m not feeling it. I’m going to take the rest of the day off.” Or, “Maybe I should go watch a movie to get some inspiration.” You’re dying. Every second is valuable. You have to WRITE. And you know what? It shouldn’t be hard. You’ve already outlined. So you know where your script is going. If you run into a tough scene, switch over to a later scene. Doesn’t matter if this isn’t the way you usually write. YOU’RE DYING. You need to maximize your time. ABW. Always be writing!

Weeks 11-15 – Feedback and Rewrite

7) FEEDBACK – Afterwards, give it to a few friends/family. Now this is important. You need to convince your friends/family to be honest. A pat on the back does nothing for you. You need them to mean, cruel, heartless. Get them to tell you what works and what doesn’t work. They’re your friends and your family so they’re always going to be too nice, but I’ve found that if you ask them pointed questions, their true feelings start to come out. You’ll hear frustration, indifference, disbelief, impatience. So keep track of when those reactions come up and star those parts of the script as problem areas.

8) REWRITE – I would love to have more than a month for my rewrite but time is running out man! The good news is we picked a clean narrative (a main character with a goal he desperately wants to achieve) so the fixes shouldn’t be too complicated. Isolate the big problems in the script. Come up with solutions. Start the rewriting. After you’re finished, polish it up and make it as easy to read as possible. No long paragraphs. An easy succinct style.

9) PROOFREAD – You may only have 3 months to live, but you’re not stupid. You’re not going to go all this way only to get your script rejected because of too many typos in the first ten pages. I don’t care how much blood you’re coughing up. Make that script as clean as a whistle.

Weeks 16 – 24 – Sell it

10) RESEARCH – This is the place where most writers fail. They have their script but no place to go with it. That’s why I’ve given you 8 weeks for this section. This is going to take some effort on your part and probably require you to do things you’re not comfortable doing. Well suck it up Sally. You only have two months to live. If you can’t face your fears now, when can you? To ease you into this tumultuous section, I’ll start with something simple. RESEARCH! Subscribe to IMDBPro (don’t sweat the 20 bucks, you can’t take money to the afterlife) and write down the producers names/companies who worked on every movie that’s ever been like yours in the last 10 years. Do the same with the Black List. Do the same with any spec sale that hasn’t been made yet. Find the producers who bought/worked on those movies and write down their phone numbers (IMDBPro has most phone numbers. Savvy googling should find you the rest). Your list should have somewhere between 100-300 names.

11) CONNECTIONS – Okay, we’re almost in the arena – where you’re going to fight to the death. It’s going to be unpleasant. So here’s one last area to prepare you. You need to call every single person you know and ask them if they know anyone in Hollywood who will read your script. Depending on where you live, this might be 3 people. It might be 20. And chances are, they won’t be Spielberg or Cameron. But they’ll be working in the industry. And if they like your script, they just might know someone else to pass it on to. So call these people up. Be excited. Thankful. Chatty. Don’t bring up your chemo treatments. Say that you’d love the opinion of someone who works in the business. Would they read your script? They’ll probably all say yes which will put you in the perfect mindset for the most difficult part of this entire process. So pump yourself up. It’s time to start calling all those numbers you researched.

12) COLD CALLING – Cold calling sucks. But guess what? You’re dying. Cold calling can’t be worse than that can it? You’re going to go directly to the producers here. You don’t have time to wait for agents. Now, pay attention, because cold calling is an art. You’re going to call these people and be upbeat, nice, cordial, energetic (but not TOO energetic) and professional. You’ll get the secretary, who will probably sound impatient, but don’t let that phase you. You have 199 other people to call if she stonewalls you. But she won’t. Because you’re going to keep this simple. You’ll say something to the effect of, “Hi, this is Jane Smith. Is Mr. Adams (the producer) in?” “May I ask what this is in regards to?” she’ll probably ask. “Yes, it’s about my script Act of Vengeance.” Depending on the status of the producer, you may or may not get through to them. A quick detail to remember. There’s a ton of turnover in these secretary jobs so this person is probably just as new to this as you. DO NOT BE INTIMIDATED.

13) PRODUCER CONVERSATION – I hope you don’t mind lying, because you’re about to. This is what you’ll say: “Mr. Adams. Hi, this is Jane Smith. You read one of my scripts awhile back and I have a new one I’d love to send over.” Now you may be afraid of getting caught in this lie. Don’t. Producers receive a TON of material. An endless amount. They can barely remember what they read last week, much less something they read two years ago. And they don’t read most of the scripts anyway. So there’s no way they can prove that you’re lying. If they press you, be vague. “Where do we know each other from?” “Oh we haven’t formally met but I sent my other script to your assistant a couple of years back.” If everything works out, he’ll say, “Sure, send it over.” But, he might say, “Yeah, have your agent send it over.” Don’t freak out. An important thing to know is that there are a lot of solid writers out there without representation or “between” representation. So just say, “Oh, I’m not represented at the moment. Is it okay if I get a release form from your assistant?” He might say yes, he might say no. But you should probably hit with at LEAST 30% of these calls. So if you call 200 producers – that’s 60 PEOPLE READING YOUR SCRIPT! And not just any people – but targeted people who make your kind of movie.

14) IF YOU’RE NOT A LIAR – Now if you don’t like lying (wimp), here’s an alternative approach. You’ll say: “Mr. Adams. Hi, this is Jane Smith. I just finished a script that I know your company will love. Can I send it over?” Don’t let any awkward pauses derail you. After collecting himself, he might say something like, “Have we met before?” Just reply, “No, not personally. But I know how much you love these kinds of movies and I really think you’ll like this. It’s about [recite your logline.]” And THIS is where all that hard work you did at the beginning will pay off. Had you gone with your passion project idea (a wheat farmer who’s been a victim of domestic abuse goes on a spiritual journey through Peru), you’d get hung up on. But because you test drove and went with an intriguing high concept idea, the first thing that will go through that producer’s mind is, “Hmmm, that actually sounds like it could be a movie.” “Sure, send it over,” he’ll say. If he says he can’t accept unsolicited material, ask if you can sign a release form. If he still says no, thank him for his time and hang up. Then, either right then or later, call back and talk to the secretary. Tell her it didn’t sound like Mr. Adams had time to read your script, but is there any way she could read it? Remember, these secretaries are desperate to move up. If they bring their boss an awesome surefire 300 million dollar box office hit, they’re set for life. Tell them you’ll be happy to sign a release form. They might say no but don’t sweat it if they do. Just go on to the next person.

15) STAY ON IT – Keep working the phones. Call people back. Remind people to read your script. 2 weeks is the industry standard for you to politely check in and ask if they’ve read your script yet. I didn’t realize how important this was until I started getting submissions myself. Even when I like an idea, I sometimes get bombarded with work and simply forget about it. A number of Amateur Friday reviews came directly from people reminding me about their screenplay. Keep doing this. Stay on top of it. You can’t get a yes unless they read it so you’ll have to remind them until they do. Even if that reminder is from your death bed!

16) CELEBRATE – You wrote something fun and marketable. The plot was clear. The story had enough twists and turns to keep the reader interested. The main character was perfect for a movie star. And you got it to enough people that it finally found someone who fell in love with it. You did it. You sold a screenplay. Now go party your ass off before you kick the bucket.

If I had no Hollywood connections whatsoever, this is the path I’d take without question. Now all you have to do is convince yourself you’re going to die in six months and write your script. Just make sure to send me 10% when you sell it.

So last week we talked about adding conflict to scenes. Today, we’re gonna take that one step further and talk about specific ways to improve your scenes. Now the majority of what makes a scene great comes from what you’ve done beforehand. The structure of your story. The development of your characters. How you craft your relationships. You have to set all that stuff up in order to pay it off later. For example, the Jack Rabbit Slims scene in Pulp Fiction doesn’t work if it’s the first scene in the movie. It works because of what’s been set up beforehand. That said, every writer should carry around a bag of tricks for when their scenes aren’t working. Don’t have a bag of tricks? Not to worry. I’m about to give you one. Here are 10 tricks you can use to make your scenes kick ass.

ADD A GOAL TO THE SCENE

Well surprise surprise. Here we have another article and Carson’s harping on about that “goal” thing again. Well hold onto your seat sister, because this might be the most important advice I give you all day. In short, a goal gives a scene focus. Just like a goal gives a movie focus. Say you have two characters at a bar. You need to get in some exposition about how one of them is having troubles at work. Problem is, random conversation gets boring fast. However, if you switch the scene around so that your hero needs a solution (goal) for this work problem before tomorrow morning, now all of a sudden your scene has purpose. Both characters are working towards a common goal. You can still throw in a bunch of funny banter, along with necessary exposition, but since you’ve established that there’s a purpose (a goal) to the scene, we’ll be more interested in what they’re talking about. Adding goals to scenes is one of the easiest ways to make them more interesting.

TURN THE SCENE INTO A SITUATION

I got this one from the billionaire screenwriters over at Wordplayer. Remember, every single scene should be entertaining on some level – even exposition scenes. That means instead of just pushing your plot along, push it along in as entertaining a way as possible. Let’s look at Back To The Future. There’s a scene early on where Marty stumbles into town and must find out where 1950s Doc lives. So he goes into the diner, looks him up in the phone book, and finds the address. Technically, that’s all you need to get Marty to the next scene. So the scene’s over. Right? Well, no. Because it’s boring. There’s no situation there. It’s just a character moving from point A to point B. So Zemeckis and Gale throw on their creative caps and get to work. Marty runs into his father, who’s being bullied by Biff. We get a fun scene where they meet each other for the first time and then Marty has his first confrontation with the movie’s villain. You’ve taken a simple plot-point scene and you’ve turned it into a situation. Now this might seem obvious in retrospect. Of course Marty runs into his dad and Biff. The story can’t work without it. But when you’re staring at a blank page, you don’t see all that stuff yet. You have to find it. So if your scene feels thin or boring, turning it into a situation is definitely going to spice it up. And who knows, you might just find an exciting new plot direction along with it.

ADD A THIRD CHARACTER

This is an old but effective trick. A quick way to make a scene between two people more interesting is to add a third person. A great example of this is in Notting Hill. It’s the scene where William goes to talk to Anna (Julia Roberts) but her press junket is running late. Will is ushered into her room under the assumption that he’s a journalist. Now if you would’ve played this scene with just two characters, the dialogue would’ve been on the nose and boring. “Thanks for coming.” “You’re welcome. What are you up to?” “Nothing. How about you?” Borrrrrrrring. So instead, they keep sending Anna’s handler into the room to check up on them, forcing William to keep up the façade that he’s a journalist. He has to come up with questions. He has to pretend like he’s seen the movie. It adds a ton of flavor to what otherwise would’ve been an average scene. The trick is, you want the third person to agitate matters. They have to complicate things somehow. That’s where you get your entertainment.

UP THE STAKES IN THE SCENE

Hey, this may sound familiar. What are the stakes of your scene? Because if nobody in the scene has anything on the line, there’s a good chance you’ve just sent your characters to Boringsville. How do you know if the stakes are high? Ask yourself: Does my character lose anything significant if he doesn’t get what he wants? Also: Does my character gain anything significant if he gets what he wants? Look at the famous scene in The Princess Bride where the Man In Black swordfights Enigo Montaya. Both characters have an incredible amount at stake. If the Man In Black loses, he won’t be able to save the life of his true love. If Enigo Montaya loses, he’ll never be able to avenge his father’s death. That’s why that swordfight is so exciting. Contrast that with any of the hundreds of swordfights in the Pirates Of The Caribbean franchise where we feel nothing, because either we don’t know what’s at stake or what’s at stake is so murky that we don’t care. Not every scene will have astronomical stakes, but you can always make a scene better by upping the stakes.

DRAMATIC IRONY

This is hands down one of the best ways to juice up a scene. Give the audience knowledge that someone in your scene – or group of people in your scene – don’t know. This is the often referred to “bomb under the table” scenario. If two people are talking at a table, it’s boring. But if two people are talking at a table and we know there’s a bomb underneath about to go off, it’s interesting. Just remember, the bomb can be anything. Let’s say you’re writing a horror movie and your beautiful 20-year-old heroine is coming home after a night out. She comes into her apartment, puts her things away, washes her face, gets ready for bed, and as she opens her closet to throw her clothes in, a man leaps out and tackles her. Hmmm, that’s pretty boring. Let’s go back and do that same scene over again, except this time, before she walks in, show us that the man is inside the house, waiting for her ahead of time. Ohhhhhhh. Okay. Now we have dramatic irony. We know she’s in trouble but she doesn’t. Even the most mundane act – washing her face – becomes interesting. Dramatic irony people. It’s a writer’s best friend.

ADD A TICKING TIME BOMB

Any time you add urgency to a scene, everything about the scene becomes more exciting. That’s because urgency creates pressure. And dialogue and action will always be more interesting under pressure. For example, let’s say you wanted to write a scene where your married couple was discussing their problems. The obvious way to do this would be to throw them at the dinner table and let them go at it. Hmmm. You can obviously make this work. But consider how much more entertaining that conversation might be if you place it during breakfast with one of the characters (or both) late for work. Now they’re rushing around, trying to get ready, while having this intense conversation. Because we know the conversation has to end soon, it’s elevated to a new level. We feel all that emotion and tension at a higher decibel level.

PLACE YOUR CHARACTER SOMEWHERE HE OR SHE DOESN’T WANT TO BE

Remember, if there are too many scenes in your movie where your character is comfortable, there’s a good chance your movie is getting BORRRRRRRRRING. An easy way to add tension to a scene is to put your character in a situation they don’t want to be in. The Deli Scene from The Wrestler that I highlighted the other week is a good example. The last place The RAM wants to be is at that deli. You can see this in a lot of scenes. The Cantina scene in Star Wars. They don’t want to be there. It’s dangerous. Lester Burnham being dragged to his wife’s real estate convention. He doesn’t want to be there. You obviously have to mix in scenes where characters are happy in order to set up those moments, but just remember, you have to keep making your characters uncomfortable or else the situations they’re in become boring.

WANT

Make sure you know what each character wants in your scene. The stronger you can make that want, and the more that “want” conflicts with the other character’s “want,” the more entertaining a scene you’re going to write. So let’s say your main character wants to ask the Starbucks cashier out on a date. That’s his want. So the character gets up to the cashier, and his side of the conversation is very strong, but for some reason, the cashier’s side is boring and lifeless. Why is this? It’s likely because you don’t know what she wants. Maybe she’s at the end of a double shift and all she can think about is getting home. Immediately your scene becomes more interesting. Your hero has been prepping for this moment all week, and she won’t even look at him because she keeps glancing at her watch and that clock up on the wall. Even when she is looking at him, she doesn’t care because her “want” is so strong. Any time you have two strong conflicting wants in a scene, chances are you have an interesting scene.

ELIMINATE THE DIALOGUE

Forcing yourself to come up with a visual solution instead of a spoken solution can do wonders for a scene. How do you accomplish this? Start off by asking yourself, what’s the point of this scene? Then, instead of trying to convey the answer through dialogue, do it visually, through action. Show us. Don’t tell us. For example, say you want to convey that a girl is frustrated with her father. The obvious way to do this would be to have her dad ask her why she’s been quiet lately. She tells him he wasn’t around last week when she needed him most. Things get heated. She eventually storms off saying something to the effect of, “You’re such an asshole.” Instead, why not write a scene where she’s in her bedroom and hears her dad coming. She quickly grabs her headphones, throws them on, and pretends to do homework. He peeks in, sees she’s busy, and leaves. If you really wanted to drive it home, maybe she gives him the finger after he leaves. Now the truth is, in this day and age, you’re not going to have many scenes without dialogue. But you’d be surprised at how much better your scene becomes when you approach it from a “show don’t tell” perspective. You’ll probably end up adding dialogue back in, but the scene will have a more visual flair and therefore be better.

ADD AN OBSTACLE

Something we’re all guilty of in our scenes is having tunnel vision. We know what we want out of the scene, so we write a straightforward version of it. For example, if we’re writing a breakup scene, we simply write our character break up with the other character. The scene does what it’s supposed to do so we’re happy. But in the end, the scene feels flat. A breakup is supposed to be an entertaining moment. Why is ours so boring? It’s likely because the scene is too predictable – too straightforward. You need to add an obstacle, a twist, something unexpected. For example, in Say Anything, Diane is going to break up with Lloyd. But as she’s preparing to do it, Lloyd goes into this big thing about how much he likes her and how they’re going to do all these things together and he tells her about the letter he wrote her. All of a sudden, breaking up isn’t so easy. And it’s all because we added a little obstacle – an unexpected roadblock. I think whenever a scene is too easy, you should be looking to add some sort of obstacle to throw the scene out of balance.

I guarantee that these tools will improve your scenes. It has to be the right fit for the right scene, but the solution to one of your yucky scenes is probably listed above. The only thing left is to figure out tip number 11. I’m gonna leave that one up to you guys. What tricks or methods do you use to improve your scenes? Maybe we can come up with the ultimate list and sell all of our screenplays to Fox by the weekend. Suggestions in the comments section please. :-)

Last week we talked about establishing conflict through characters, relationships, and external forces. During the article, I casually mentioned the importance of conflict within scenes as well. Many of you expressed interest in hearing more about that, so I decided to expand my conflict ramblings to a second week.

Indeed, virtually every scene in your screenplay should have some element of conflict if it’s going to entertain an audience. I cannot stress this enough. One of the biggest mistakes I see in screenplays is boring scenes. Scenes that only exist for characters to spout exposition, to reveal backstory, or to wax philosophic. I’ve referred to these scenes before as “scenes of death.” The quickest way to make these scenes interesting is to add conflict.

The basis for all conflict comes from an imbalance – two forces opposed to one another (wanting different things), or even one force wanting something it can’t have. Usually these forces are represented by your characters. But they can be external as well (if our character is racing towards the airport to tell his girlfriend he loves her, the opposing force might be a traffic jam). So when you sit down to write a scene, you’re always looking to create that imbalance, that unresolved issue, to add an entertainment factor to the sequence.

Having said that, it should be noted that in rare circumstances, you can get away with no conflict. For example, in order for the scene in Notting Hill to work where Anna invites William up to her hotel only to find her boyfriend there (a scene heavy with conflict), we needed a few scenes with the two having a great time together. So eliminating the conflict in those previous scenes actually made the conflict stronger in this one. So as long as you have a purpose for not using conflict, it’s okay (however I would always err on the side of adding conflict).

In true Scriptshadow form, I’ve decided to highlight 10 movies and look at how they create conflict within their scenes. This should give you a clearer picture on how to apply conflict to scenes in your own screenplays.

Meet The Parents

Scene: The Dinner Scene

Conflict: The conflict here is simple. Greg wants to impress Jack so he’ll approve of him marrying his daughter. Jack wants to expose Greg as the inadequate choice for his daughter that he is (two opposing forces – a clear imbalance). This is a great reminder that the best conflict has usually been set up beforehand. So we’ve already established in Greg’s earlier scenes how important getting married to Jack’s daughter is (testing his proposal on one of his patients, organizing her preschool class to help him propose). We’ve also established how reluctant Jack is to accept Greg (when he first shows up, Jack disagrees with him on almost everything). This is the most basic application of conflict in a scene, but as you can see, even the most basic conflict can make a scene highly entertaining.

The Sixth Sense

Scene: Malcolm tries to get Cole to talk to him.

Conflict: This is a very understated scene, but the conflict is well-crafted. Malcolm wants Cole to trust him. Cole is resistant to trusting Malcolm. Again, a simple imbalance. One person wants one thing. Another person wants the opposite. Night cleverly draws the scene out by building a game around it – if Malcolm guesses something right about Cole, he has to take a step forward. If he guesses wrong, Cole gets to take a step back. So you actually feel the conflict with every question.

Back To The Future

Scene: Marty asks Doc to get him back to the future.

Conflict: Once Marty convinces 1950s Doc that he’s from the future, Doc lets him inside. Now at this point, the two are on the same page. They both want to get Marty back to the future. So there’s no conflict between the characters. Instead, the conflict comes from the fact that Doc doesn’t believe it’s possible. So again, two forces are colliding with one another and need to be resolved. At the end of the scene, they realize that the lightning can send him back to the future, and the conflict is resolved (sometimes conflict will be resolved by the end of a scene and sometimes not – it depends on the story and what you’re trying to do).

Rocky

Scene: Multiple scenes.

Conflict: One of the reasons Rocky is so great is because almost every single scene is packed with conflict. Whether it’s Rocky trying to get a resistant Adrian to go out with him. Whether it’s Rocky getting kicked out of his gym. Whether it’s Mick begging Rocky to let him coach him. Whether it’s his constant clashes with Paulie (and his destructive behavior). Whether it’s him telling a resistant girl to stop hanging around thugs and do something with her life. If you want to know how to create conflict within scenes, pop this movie in your DVD player right now.

Toy Story

Scene: Birthday scene.

Conflict: In this scene, the army men sneak down to Andy’s birthday to report what the new presents are. The conflict stems from trying to report the presents without getting caught. Remember, if it didn’t matter whether the army men were discovered or not, there would be no conflict (and therefore no drama) in this scene. The conflict comes from the fact that if they’re seen, they’re screwed. This is actually one of the reasons the Toy Story franchise is so successful. Because nearly every scene is built around this imbalance. The toys have to pretend to be inanimate whenever humans are around. That means every scene is packed with conflict.

The Wrestler

Scene: Deli scene

Conflict: In this famous scene, the conflict comes from the fact that everything in The Ram’s life is falling apart – his health, his family, his profession – and the last place he wants to be is at his $10 an hour deli job. So there’s conflict within the character before the scene even begins. But when his boss starts getting on his nerves, when customers start pushing him, when someone recognizes him, he starts losing it. Those multiple forces pushing up against him are the conflict that makes this scene so great. It’s also another reminder that the best conflict is usually set up ahead of time. This scene doesn’t work if it’s the first scene in the movie. It works because we’ve experienced the downfall of this character. We know what he’s been through. Therefore we understand why he doesn’t want to be here.

Pretty Woman

Scene: Vivian comes back to his hotel.

Conflict: In this scene, Edward picks up Vivian on the streets and brings her back to his hotel. I specifically picked this scene because it’s a scene that amateur writers always screw up. What’s the purpose of this scene? The purpose is for these two characters to get to know each other. A very common scene in a romantic comedy or any “guy meets girl” movie. However, bad writers will take this scene and try to fill it with a bunch of clever dialogue, exposition, and backstory. If you go that route, at best you’ll have an average scene, and more likely a terrible one. Here’s the thing. This scene *does* have clever dialogue, exposition, and back story. So then why does it work? Because the writer added an element of conflict. Edward wants to talk whereas Vivian wants to get down to business. He wants to get to know her. She wants to collect her money and run. So there’s this little dance going on during the scene – the two characters wanting different things – that allows the writer to slip in clever dialogue, exposition, and backstory, without us realizing it. We’re so entertained/distracted by that dance, that all the story machinations slip under the radar. This is why conflict is so powerful. The right dose can turn an otherwise boring scene into an entertaining one.

The Other Guys

Scenes: All of them.

Conflict: One of the easiest genres to write conflict in is the buddy comedy. That’s because every single scene will have your characters clashing with each other. This is why The Hangover was so popular. This is why Rush Hour was so big. The conflict is definitely artificial, however because it’s a comedy, it works. The trick with these films is to vary the conflict from scene to scene so we don’t tire of it. For example, in an early scene at the office, Mark Wahlberg yells at Will Ferrell for being a pussy. It’s an intense scene with a lot of conflict. However later on, when Mark has dinner with Will’s wife, the conflict is more subtle. Mark keeps bothering him about the fact that there’s no way this could really be his wife. Not every scene needs to be nuclear charged with conflict. You need to mix it up just like you need to mix up any aspect of your screenplay.

Pulp Fiction

Scene: Jack Rabbit Slims

Conflict: The uninitiated screenwriter will look at this scene between Vincent Vega and Mia Wallace and think it’s just a bunch of cool dialogue. Don’t be fooled. This scene’s awesomeness is based entirely on its conflict. Vincent Vega wants something he can’t have – Mia Wallace. Why? Because Mia Wallace is the wife of his boss. What’s so great about this scene though is how hard Tarantino pushes the conflict. If all that was going on here was Vincent wanting Mia, there would be conflict, but not that much. It’s the fact that Mia is throwing herself at him that’s making this so difficult. The more tempted Vincent is, the more difficult his choice becomes. Another lesson here is that the conflict doesn’t only have to come from the characters inside the scene. It’s not Mia who doesn’t want Vincent here. It’s her husband who’s preventing her from being with Vincent. So the conflict in this scene is a little trickier than normal, but it shows that if you think outside the box, you can find conflict through other avenues.

No Country For Old Men

Scene: Anton and the gas station attendant.

Conflict: In this scene, which is probably one of the best scenes of the last decade, Anton pays for gas but gets annoyed when the attendant makes an offhanded remark about where he’s from. The conflict here comes from two places. The first is through dramatic irony. We know how dangerous Anton is. We know what he’s capable of. So we fear what he’s going to do to this man. Dramatic irony is basically conflict between the character and the audience member. It’s usually us not wanting a character to do something. So the imbalance has actually broken the fourth wall. The other conflict here is basic. Anton refuses to let the attendant off for anything he says. Every sentence is shot back in his face. The longer the conversation goes, the more dangerous (and more conflict filled) the scene becomes.

The idea is you want to look at every scene and ask the question, “Where is the conflict here?” Where are the opposing forces? Where is the imbalance? If everything is too easy for the characters in your screenplay – if everybody agrees on everything or the characters don’t face any resistance – there’s a good chance your scene is boring. There are instances where it’s okay (such as the Notting Hill example) but for the most part, you want some conflict in your scene. So get back to that script you’re working on and start making all those scenes more interesting by adding conflict. Good luck! :-)

So in the last two weeks since I wrote the GSU article, I’ve been asked a lot of questions about movies that ignore some, or in a few cases, all of the GSU variables and still manage to work. The truth is, goals stakes and urgency aren’t the only way to keep your audience interested. They’re just the most effective way. But because the other methods for keeping a story interesting are more intricate and difficult to apply, they require more skill and experience to pull off. Now in the past, I’ve merely alluded to these options like a magical potion you needed to attend Hogwarts to get a hold of. But today I’m going to get into a few of these subtleties by breaking down the most important element of GSU – the goal.

Everything starts with the goal. The stronger and more clear your goal is, the more drive and purpose your story will have. Get the Ark (Raiders). Find the treasure (Goonies). Win the fight (Rocky). How much simpler and easier is it to understand than that? However, there are different kinds of goals you can use to drive your story. None of these goals are going to give your story the same horsepower that that giant tangible goal will give you. But they can still work under the right circumstances. Let’s go over each of these goals and then look at some movies that utilize them.

CHANGING GOALS

It is perfectly okay for goals to change during the course of the movie. Things happen that change the circumstances for the characters all the time. It makes sense then that what the characters are going after would change as well. If you look at Star Wars, the original goal is to get the secret Death Star plans to Princess Leia’s home planet. But when they get to the planet, it’s no longer there, and they’re captured by the Empire. Therefore, the goal has changed. They must now escape the Death Star (after saving Princess Leia of course). Once they finally get to the Rebel Base, an entirely new goal presents itself – destroy the Death Star. So it’s completely okay to change goals over the course of the story. Just make sure that each goal is powerful.

A MYSTERY

Some movies are structured so that we don’t know the goal yet. Instead, a mystery is what drives the story. Assuming that this mystery is intriguing and that we want to know more about it, you technically don’t need a goal. This is how The Matrix is structured. The first 45 min. of the movie is designed as a mystery – What is the matrix? Because they did such a good job making that mystery compelling (we see normal people defying physics), we stick around to learn what it’s about. Once we do find out, the movie switches to a series of goals. Learn how to use your new powers. Go see the Oracle. And eventually, save Morpheus. But it all started with a mystery.

THE THROWAWAY GOAL

The throwaway goal is a goal a lot of indie movie writers use to give their stories a bare-bones narrative, even though the goal itself isn’t that important. This is a dangerous goal because it’s not a very active one. Sideways is a good example of a throwaway goal. Paul Giamatti’s friend claims that his goal on this trip is to get Paul laid. But in reality, that’s not really that important. What’s important is the development of these characters over the course of their journey. It is very rare that a throwaway goal screenplay will be purchased on spec. These movies just don’t have enough horsepower for studios to take a chance on them. Most of the time, these movies will come from writer-directors who are able to bypass the spec purchase stage and make the movies themselves.

SOMEONE BESIDES YOUR MAIN CHARACTER HAS THE GOAL

Now you’re moving into tricky territory because preferably, you want your main character having the central goal that drives the story. But there are instances where you don’t need this as long as *someone* has the goal. So in Good Will Hunting, it’s Prof. Lambeau who has the main goal. He’s trying to train Will so he can reach his potential. The biggest problem you run into with this approach is that your main character ends up becoming too reactive, or worse, inactive, and will therefore come off as boring. Good Will Hunting is one of the few movies where I’ve seen this work so I would be weary of using it yourself.

OPEN ENDED GOAL

The open ended goal is a goal without a clear end point. This goal is never as powerful as a tangible goal because the finish line is murky. Audiences like people who have clear and easy to understand motivations because it’s easier to understand what’s going on. However, this goal has been shown to be effective under the right circumstances. In Jerry Maguire, Jerry McGuire doesn’t really have a goal other than “to get back on his feet” or “to put his new business on solid ground.” (You may be able to make the argument that Rod Tidwell has the goal that drives the story – to get a new contract – but let’s not confuse ourselves). This type of goal still works mainly because it forces your character to be active. Because your character is still going after something, he’s constantly out there doing things and pushing the story forward.

THE NEGATIVE GOAL

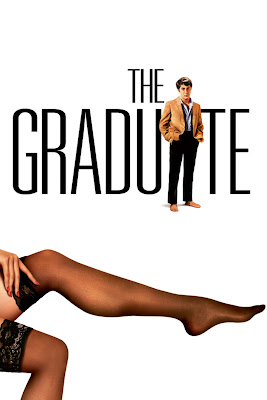

The negative goal is when your character is trying not to do something. In my eyes, this is one of the most dangerous goals to give a character because it sets up a movie that does the exact opposite of what movies are good at doing, which is telling stories about people going after things. The most famous example of this is, of course, The Graduate. In that movie, Dustin Hoffman’s goal is to *not* make a decision. For this reason, Dustin is mainly reacting to everything around him, meaning everything is shining except for the main character, which modern audiences just have a really tough time accepting. Either way, in a story where there is a negative goal, eventually a positive goal needs to emerge. At a certain point, Dustin Hoffman’s goal becomes to get Mrs. Robinson’s daughter.

THE HIDDEN GOAL

Probably the most difficult goal to pull off is the hidden goal. This is a goal our main character has but we don’t know that he has it until the end of the movie. The reason this is so hard to pull off is because for 95% of the movie, the character appears to us to be inactive, which in most cases is boring. The most famous example of this is The Shawshank Redemption. For all we know, Andy Dufrene is just hanging out in jail trying to live his life. What we find out in the end though, is that everything he did was a plan to get him out of here and therefore a part of an extremely strong goal. While this situation tends to create a great ending (because of the surprise factor), it means you have to use a variety of subtle and less dominant storytelling techniques to make the other 95% of your screenplay work, which is really hard. If you plan to use this technique, I wish you luck, because it ain’t easy.

THE QUESTION

A close cousin to the mystery is the question – which is basically a central question that drives the story. The place where you’re going to find this the most is in romantic comedies, where neither character may have a clear goal, but the question of “will these two get together?” drives our interest. The most important thing to remember when applying a question instead of a goal, is that your character work has to be impeccable. And if it’s a romance, we have to like your characters (or at least be highly intrigued by them) and we have to want them to be together. If we don’t have that, then we don’t care about the answer to the question. It’s also a good idea to add some sort of work goal or subplot goal to add some drive to your story in these types of movies. If all that’s driving your story is a question, your audience might get bored quickly.

Now let’s look at a few random movies that don’t have the traditional dominant goal, and see which of these options they used and how they integrated them.

BEFORE SUNRISE – Like a lot of romantic movies, what’s driving the story here is a question – will these two people end up together? Or, if you want to get more specific, what’s going to happen when the night is over? Linkletter did a great job creating a really tight time frame so that the script had urgency. Even though the conversations themselves were somewhat mundane, because the end of the night was always so near, each of these conversations is interesting in a way they wouldn’t have been had the time frame been spread out over two weeks.

SWINGERS – Swingers is one of the trickier narratives you’ll see in a screenplay. For a lot of reasons, it shouldn’t have worked. It’s basically driven by the open ended goal of Mikey trying to get over his girlfriend. The reason it’s tricky is because Mikey isn’t actively trying to get over her. It’s Trent who wants Mikey to get over his girlfriend so he can have his friend back. That’s why they go to Vegas. That’s why they go out all the time. That means you not only have an open-ended goal, but a secondary character who has the main goal. What’s important to remember is that even though both goals are relatively weak in comparison to what normally drives movies, Trent’s goal forces the characters to get out there to do things and be active. As long as your characters are doing things, your story is going to have drive.

FERRIS BUELLER’S DAY OFF – Ferris Bueller is one of the few successful movies that uses a negative goal. The goal here is to not get caught. Now if you wanted to, you might be able to switch this goal around and say it’s for this trio to try and make it through the day. But since they’re constantly being chased and constantly avoiding others, what’s driving the story is mainly the goal of not getting caught.

THE SIXTH SENSE – The Sixth Sense uses three methods to drive its story. The first is an open ended goal. Bruce Willis’s goal is to help this kid. Since we don’t know what constitutes the endpoint of that goal, that’s why it’s considered open ended. The second is a mystery. There’s something wrong with this kid and we want to know what it is. Once we do find out what it is, a set of changing goals (to help each of the ghosts) finishes up the story.

ROSEMARY’S BABY – Another tricky screenplay to break down in that it doesn’t have any clear objectives for its main character. I would probably categorize Rosemary’s Baby as a negative goal in that the main character is simply trying to make sure nothing happens to her baby. Now like I mentioned above, whenever you have a negative goal, you eventually want your character to have an active goal. That’s what happens here when Rosemary starts suspecting something is wrong. She begins investigating the people she’s dealing with, looking into the possibility that they’re a cult.

The thing you have to remember with screenplays is that each story is unique and no storytelling technique is set in stone. You have to adapt sometimes. You have to improvise. And don’t forget that some of what drives these stories is open to interpretation. I’m not claiming that my examples are perfect. But they should give you a better idea of the different kinds of options you have when constructing your story. The idea is to get to a point where you can start using all of these options interchangeably and when needed, sometimes three or four times in the same screenplay, kind of like what The Sixth Sense did. But it takes time and it takes effort and it takes lots of practice to learn to use all of them. So get out there, keep writing, and keep improving. Good luck!