Read this week’s Amateur Offerings collection and offer constructive criticism below, plus vote for which script you want to be reviewed!

TITLE: Blood and Sangria

GENRE: Comedy Horror

LOGLINE: After agreeing to visit his sister in Marbella, Spain, perennial loser Morgan Maloney realizes he has made the mistake of his life when his schizophrenic alter ego, the serial killing and out of control psychokiller– Mister Galloway – rears his ugly head.

WHY YOU SHOULD READ: Who wouldn’t enjoy a light hearted tale of love in the Spanish sun with a psychopath akin to Patrick Bateman, Don Logan and Ben from Man Bites Dog.

WHY YOU SHOULDN’T READ: Copious foul language, extreme gory violence, auto-eroticism, bondage, murder, infanticide, blood, guts and more foul language and death. – And yet I would be surprised if you didn’t laugh out loud while all this stuff is going on. If all the blue dialog, action and death was removed it is after all a love story and tale of sibling redemption and resolution and not just an aimless goriest. Please enjoy and don’t think bad of me for writing such a fantastically horrible gross out script – it is Mister Galloway who made me do it.

TITLE: Weekend Dad

GENRE: Dramedy

LOGLINE: A down-on-his-luck, divorced father, fearing he and his son are growing apart, struggles to get his life together and compete with the new, larger than life, billionaire stepdad.

WHY YOU SHOULD READ: I just had my first child, a boy. Well, my wife actually had him. I was there when he came out. And participated when he was conceived. I barely remember either event due to lack of sleep. These babies are tough to get on a schedule. Anyway, I look at my son and hope he will be a good person. I look at him and hope we stay close and nothing will break our bond. I know I don’t have to worry about this for a while. I am one of his only sources for clean diapers.

TITLE: I Am Ryan Reynolds

GENRE: Comedy, Fantasy

LOGLINE: Ryan Reynolds’ marriage, career, and sanity are threatened by a plastic surgery treatment that allows anyone with $10,000 to look like him.

WHY YOU SHOULD READ: You read the title, you read the logline, and now you’re wondering if the author is: 1. a crazy person, 2. a huge Ryan Reynolds fan, 3. someone who needs to get out more, or 4. some combination of those three things. In any case, “I Am Ryan Reynolds” is a surreal Hollywood satire with an unlikeable protagonist and very specific casting possibilities. It’s like “Being John Malkovich” for the common man, “Multiplicity” but with different character names, and “The Player,” except almost entirely different. Also, the descriptive paragraphs top out at two lines in length, so at the very least, the script is a quick read.

TITLE: Mgimbwa

GENRE: Animal, Drama

LOGLINE: After a chimpanzee’s community is driven from its territory in the African jungles by a rival tribe, he struggles to rise through social ranks and take back the territory once his.

WHY YOU SHOULD READ: No dreams. No flashbacks. No narration. No humans. No dialogue.

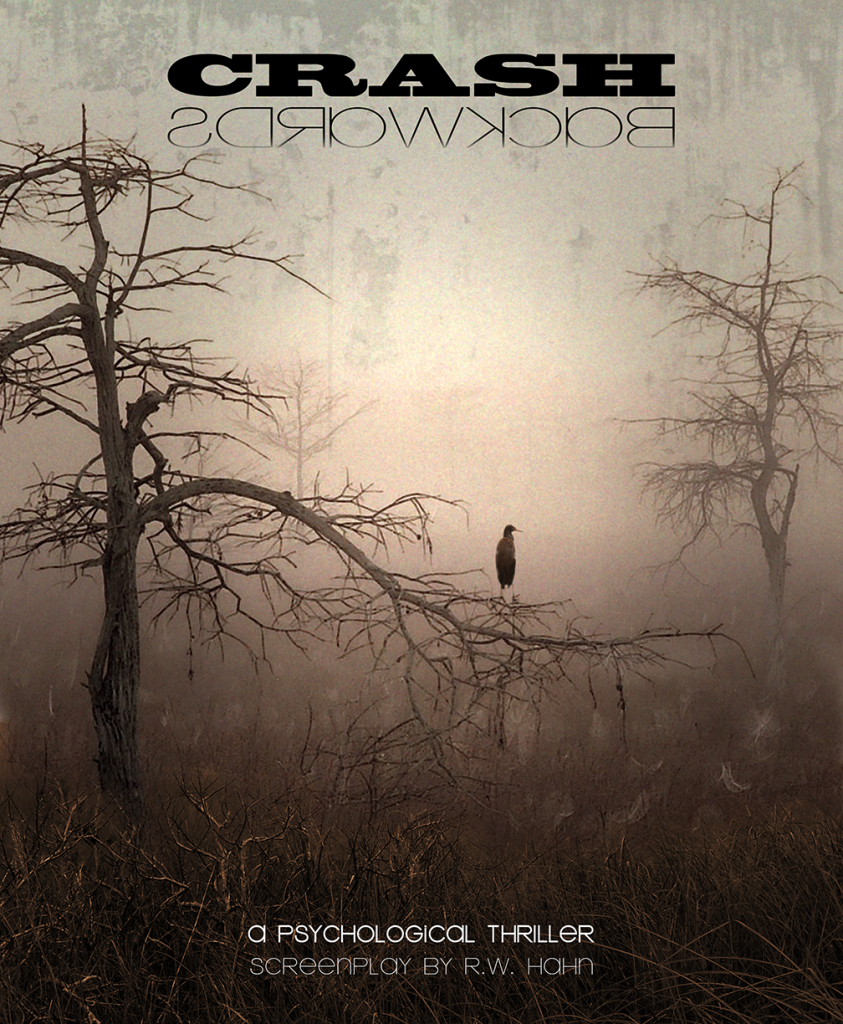

TITLE: Crash Backwards

GENRE: Thriller

LOGLINE: A happily married woman begins to question her sanity when she discovers a stalker may be her husband from another life. In her quest for the truth she must make a choice that could wipe out her existence.

WHY YOU SHOULD READ: I had this idea several years ago and have been “thinkubating” on it since then….About two months ago it all came bubbling out and I couldn’t stop writing until it was finished. — I love roller coasters in the dark. That’s what this is. It takes you on a jolting, hair raising ride in the dark, all while you try to guess the next turn. — This story is a total mind job that puts you in the seat of the protagonist. You learn as she learns. You experience right along with her never knowing what’s going to happen next. It twists and turns right up to the final reveal, then….well you’ll just have to read it to find out. Also, here’s a poster for the script.

One of you suggested this in the comments the other day and it sounded like a wonderful debate. The two biggest geek shows on TV are Game of Thrones and The Walking Dead. My guess is that both shows have a lot of crossover viewers, which means most of you are educated enough to offer your opinion on both. Therefore, I shall ask: Which is the better written show, The Walking Dead or Game of Thrones? Notice I didn’t ask which is the “better” show, but which show is better written.

In my eyes, this isn’t even a fair fight. The Walking Dead is a much better written show. I’ve never felt more worried for characters than I do during this show. At any moment, they’re in danger from either a zombie or fellow human attack, which leads to that necessary discomfort the audience must feel in order for the story to work.

The scene-writing is also top-notch, always so clever. They’re constantly setting up complex situations that don’t have clear resolutions, keeping you on the edge of your seat for up to 10 minutes at a time. My favorite scene of the year (in anything!) is the one where Rick sends his son and Michonne out to get food while he takes a nap in an abandoned suburban house. In the interim, raiders show up and take over the house, forcing Rick to hide.

If he tries to leave, they’ll easily catch and kill him. If he doesn’t, his son comes home unaware the raiders are there and they’ll kill him instead. These are the best kinds of scenes because there’s no solution. Every road traveled leads to failure. And if you set up that kind of situation, you better believe your reader/viewers are going to stick around to see what happens. The Walking Dead is filled with cleverly thought-out scenes like this.

Like any show, The Walking Dead has some good characters and some not so good characters. But on the whole, they’re good. Watching Rick fight a daily battle against losing his humanity is one of the better inner conflicts I’ve watched a main character go through. Watching inventive characters like the zombie-carrying sword-wielding Michonne emerge is beyond delightful. And meeting the best villain of the last decade in the endlessly complex “The Governor” was the cherry on top of Season 3.

Finally, The Walking Dead is really good at structuring its storylines. There’s almost always an episode goal (Find a way out of the house without the Raiders seeing you), a season goal (Get to the safe city, Terminus), and a series goal (survive and find ultimate safety) to keep everything focused and on track. There’s never a point in The Walking Dead where you’re saying, “Wait, what’s going on again?” It’s always clearly laid out.

Game of Thrones is a completely different animal, but good in its own ways. Its number 1 asset is its mythology. With The Walking Dead, the mythology is being built as we experience it. There’s not a lot of mystery there. But some of the things affecting the characters in Game of Thrones go back thousands of years. For that reason, you feel like you’re living in a truly immersive world, and every episode is a gift you get to unwrap to find out more about that world.

Another reason I love Game of Thrones is its restraint. Unlike certain fantasy franchises that throw a million pieces of fantasy at you a minute (orcs, spells, invisibility, giant spiders, talking trees), Thrones TEASES their fantasy elements. We hear about dragons, White Walkers, people coming back from the dead. But because these things are only hinted at, we don’t grow numb to them after five minutes. Instead, we eagerly anticipate when we’ll get to see them, which is another reason we’re so excited to keep watching.

Also, the relationships the show creates are captivating. Every character is connected to every other character in some way. To give you a taste, Cersei Lannister, the Queen, is secretly sleeping with her brother Jaime Lannister. We later find out that the three children the King and Queen have are not the King’s. They’re all from Jaime, which makes them inbreds. One of these children, the evil, unstable Joffrey, becomes King. Rumors spread throughout the land that Joffrey is the inbred son of Cersei and Jaime. Cersei must do everything in her power to keep this information from getting to Joffrey, since unstable kings who find out that they’re inbred probably aren’t going to take it well.

Finally, there are a lot of standout characters on the show. The empowered “mother of dragons,” Khaleesi, is exciting to watch as she goes from underdog outsider to plotting her Iron Throne takeover. Tyrion, the “imp,” played by Peter Dinklage, is lovely to watch if only because the character is so unexpected. Occasionally he’ll play the coward, only to follow it up by slapping the king. Arya Stark, the young daughter of the slain Ned Stark, is pulled from her family and must survive out in the wild. There’s the impossibly cold Cersei Lannister, whose utter hatred for the world drives her every action. Her son Joffrey is so evil, you can’t look away, lest you miss him chopping someone’s head off. The always manipulative brothel owner, Littlefinger, charms with his whispering schemes and careful chess moves in order to keep his place in power. There’s always a character to look forward to here.

But here’s why Game of Thrones doesn’t compete with The Walking Dead. Whereas The Walking Dead is always clear – we always know what’s going on and can therefore participate in every aspect of the story – Game of Thrones is too often confusing. And it all comes back to one issue – there are too many characters.

In a show like this, a show that DEPENDS on you knowing the intricate details of every relationship, being confused about who’s who can destroy the enjoyment of an entire episode. If I’m only just remembering that Robb Stark wants to kill Character A at the end of a scene where two characters are discreetly talking about Character A, I’ve missed the whole point of the scene. This happens a lot in Game of Thrones.

Tons of characters also means entire episodes go by without us seeing some of the characters. So when we finally come back to them, we barely remember what they’re up to. Again, two or three scenes may go by before we recall what they’re doing in this location in the first place. For example, I was watching Jon Snow traverse the North Mountains for an entire episode before I remembered, from a couple of episodes ago, why he was sent there in the first place.

No matter how you spin it, this is bad writing. One of the requirements of writing any story is that the reader always understand what’s going on. If they don’t, it can only be because you, the writer, don’t want them to for some reason. In other words, it’s the writer’s choice. But a lot of the confusion that comes from Game of Thrones is not due to the writer’s choice. It’s due to there being too many characters and too many camps to keep track of.

Another problem with Game of Thrones is that it errs on the side of “telling” instead of showing. It’s gotten better at this as the show’s gone on. But in the first season, there were endless scenes where two people were in a room talking. Therefore, instead of seeing troops move across the land, we hear two people TALK ABOUT troops walking across the land. Indeed, every other scene appears to be strictly exposition, which would often grind the show to a halt.

What’s interesting is that this exposition is a result of choices the writers made a long time ago. If you’re going to have a dozen factions all vying for the throne, you’re guaranteeing you’re going to have a ton of exposition. The Walking Dead doesn’t have that kind of complexity in its endgame. The endgame is simply, “survive,” so its exposition is often minimal, and we can focus more on the fun stuff, which is showing and not telling (characters getting into dangerous situations and then trying to get out of them).

Personally, I think both shows are great in their own way. But The Walking Dead is a cleaner more action-oriented story that can just “be,” whereas Thrones has to talk you through much of its world to get to its payoffs, which can sometimes feel like work.

What do you think? Which is your favorite show and why? Make sure to support your opinion with valid points about the writing. And yes, this may be the nerdiest post I’ve written this year.

note: I’m on Season 2, Episode 5 of Game of Thrones. Please note spoilers in your comments!

Long story short, I’m on a mini-vacation in Portland. Yesterday, I went over to the Food Truck Square and did a food crawl. Next thing I knew, I woke up in a park post-sundown with several half-empty bags of food and the worst stomach ache this side of a pie eating contest. A few transients in the area seemed very worried about me. They said I wandered up asking about a peanut butter pickle cheeseburger before doing something I called the “Dance of the Raspberries.” After some Chinatown-esque investigatory work, I concluded that someone had roofied my Food Truck food, although it’s unclear why they would do so. Everything was still in my wallet except for my library card. I also Googled “peanut butter pickle cheeseburger” and found out that it exists. Whether or not I consumed one yesterday and said consumption contributed to my demise is still a mystery.

When I did come home and try to do a script review for Seth Rogen and James Franco’s “The Interview,” I passed out before I could get to the finish line. But I do have a TLDR version of the review – “Pineapple Express in North Korea. Kind of funny. What I learned: With Neighbors and now The Interview, the high concept comedy is back! But I’m not sure the ‘wish’ type high concept comedies like Liar Liar are in favor. This implies that more reality-based ideas are en vogue.” I sincerely hope I recover enough to get an article up tomorrow. But Portland seems to be a bit of a Wonderland. There are so many holes to fall into, and not a lot of ways to get out. Until the next time (if there is a next time), good night, and keep Portland weird.

Genre: Drama

Premise: A record executive in the 1970s suffers a mid-life crisis and goes back to his roots, hunting out new talent for his dying record label.

About: With Boardwalk Empire ending, Martin Scorsese and Terence Winter needed a new show to do for HBO. Enter rock n roll! And because it’s Scorsese, you better believe it ain’t set in modern day. Part of me thinks Scorsese hasn’t reached 2014 yet. He’s about 30 years behind us. So for him, he’s actually directing contemporary cinema. As for Terence Winter, besides creating Boardwalk Empire, he also wrote Scorsese’s The Wolf of Wall Street, a bunch of Sopranos episodes, the 50 Cent movie Get Rich or Die Tryin’, and even a couple of episodes of Xena: Warrior Princess.

Writer: Terence Winter

Details: 59 pages (Revised Draft, April 4th 2013)

Bobby Cannavale will star in the new HBO project

Bobby Cannavale will star in the new HBO project

Do I think Scorsese repeats himself a little too much? Ummmm, maayyyy-be? I mean, he definitely has a formula down for how he tells a story. And back in the day, when that approach was new, it was fun. But now, because it’s the only thing he does, you feel like you know all the beats of his stories before he does. Once the viewer is able to predict everything, there’s no reason to keep watching.

When you couple that with rock and roll as a subject matter, you’re walking on thin ice. Rock and roll is SO hard to do well because cliché is woven into its DNA. There’s a reason “sex, drugs and rock and roll” is one of the most popular phrases in history. Those things are always lumped together and as a viewer, there are only so many times you can see a musician ruining his career with drugs.

You gotta find a different way to do it. And, as I mentioned, with Scorsese directing, I was worried whether that could happen or not. Still, I held out hope that I’d be surprised. Let’s see if I was.

It’s 1973. 40-something Richie Finestra is a record exec at the dying American Century Records. The last remaining big band they have under their label is Led Zeppelin, and it looks like they’re going to jump ship too.

At American Century, we meet Richie’s team, which includes a combination of young A&R kids who aren’t finding enough new music and a bunch of middle-aged guys who are trying to hold onto the past.

Over the course of the pilot, we experience a group of flashbacks, when Richie was an up-and-coming exec, as he signed a talented young black musician named Lester. Richie promised Lester that if he made an album for him, he’d let Lester record an album of the music he loved, which was Blues. But that never happened, and now, sadly, Lester has become Richie’s driver, his musical dreams long forgotten.

As the days pass, Richie finds himself more and more frustrated with the direction of the company, and decides to make a radical change. He demands a divorce from his wife. Then he downgrades his position at the company to talent scout. He’s going back out there and do what these young bucks can’t – find music.

But the plan is thrown for a loop when Richie finds himself at the home of a couple of business associates and things get out of hand. During a fight, one of the men is accidentally killed, and Richie and the other associate decide to toss him into an alley in the hopes that the cops will think someone mugged him. Needless to say, a homicide detective shows up at Richie’s work the next day asking questions. We’ll see just how long Richie and his secret can last.

Okay, first question. Was it cliché? Yes. Pretty much every character here did some kind of drugs. Just once – ONE TIME – I’d like a character in a music movie not to do drugs. A character who shuns it. What’s the harm? Having one original character in this world? Because I’m pretty sure not EVERYBODY did drugs in the 70s. Although if they did, it would at least explain the fashion of the time.

The story itself was okay I guess. When you’re doing a period piece, you’re doing historical fiction. And when you’re doing historical fiction, you’re trying to educate (in an entertaining way) the viewer on the subject matter, whether it be casinos, money, the mob, whatever.

So I was really looking forward to learning new things about rock and roll in the 70s. I was disappointed. There’s nothing new here if you’ve seen Cameron Crowe’s Almost Famous. And that’s not good. With a movie, you only have a limited amount of time to get into details. With TV, you have an unlimited amount of time. TV thrives BECAUSE of the details. I get that this was just the pilot, but seeing a hot young singer bang a chick then pull out a heroin needle and shoot up, or watch two executives binge on coke until they were clueless… I saw that stuff 40 movies ago.

And it’s tough. I realize that you have to show SOME drug use since it’s rock and roll in the 70s. But there’s got to be a more original way to do it.

The one original and memorable aspect of the pilot was the Lester storyline. You know right away something’s up with Richie’s chauffeur, since we never see his face. And you know pretty quickly that this up-and-coming singer in the flashbacks, Lester, is probably him. So the dramatic irony feeds this aspect of the story. We know Lester’s career is doomed from the get-go.

But I thought RICHIE was going to be the one to screw him over. In the pilot, it’s nobody’s fault. Stories become more interesting when your protagonist’s’ choices drive the drama. So if our main character isn’t responsible for this man’s dried up life, then where’s the conflict?

And I don’t like mushy main characters, protagonists stuck in that boring middle-ground. Jordon Bellforte (The Wolf of Wall Street) isn’t KIND OF a greedy crazy asshole. He IS a greedy crazy asshole. I wanted Richie to have more wrong with him. I wanted him to be that record exec who rips off artists for his own personal gain. He’s done it his entire life and finally, now, he reliazes it’s wrong. He wants to change. Instead, Richie has no conviction. He’s not responsible for much of anything that’s wrong here. He’s just around.

In the end, I’m looking for three things from this kind of TV show. I want to learn something new about the subject matter (we learn the intricate nature of how casinos work in Casino), I want strong interesting characters that I care about (like Henry Hill in Goodfellas), or I want a cool story. There were little flickers of that stuff here (a quick scene about how a record contract works, the Lester storyline, the murder) but for the most part, this felt like a retread of stuff we’ve already seen. I couldn’t get into it.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Inner conflict. You have to look at your character and ask, “What is the main conflict within this man?” “What is the thing he’s at odds with every day of his life?” Because if you can find a strong conflict within a character, you’re 90% of the way to creating a complex character. So with Richie, I was hoping to see him battling the fact that he screws singers over every day. He signs them to contracts he knows they’ll never make a penny for, and reaps the profits for his company. And it seemed to be heading in that direction with the Lester subplot, but it never quite got there.

Note: The Scriptshadow Newsletter went out Saturday. Check your SPAM and PROMOTIONS folders if you didn’t receive it. To sign up for the Newsletter, head here.

Genre: Action/Sci-fi

Premise: A young woman is forced into being a drug mule. But when the experimental drug she’s carrying inside her ruptures, she starts gaining super-human powers.

About: Taken and Transporter creator Luc Besson is back with his latest action flick, Lucy, an idea he’s had for over 10 years. He’d been looking for a way to mesh action with philosophy for awhile and Scarlett Johansson celebrating her inner badass allowed him to achieve it. Besson said that part of the reason it took him so long to write the script is that, unlike his heroine, he was only using 10% of his brain. The movie came out this weekend and went on to a huge 44 million dollar take, a surprising dominating performance when you consider she was going up against the ultimate testosterone machine, The Rock (in Hercules). Of course, that flick was directed by Brett Ratner, who I’m pretty sure only uses 2% of his brain.

Writer: Luc Besson

Details: 114 pages

I was sure this type of movie had gone out of style. As much as I love GSU, I’m growing tired of the overly simplistic action-thriller use of the model. “Taken” was fresh back when it came out, but after the clone-train hit and I read a million copycats of a) Hero tries to save someone or himself, b) the life of someone they care about or themselves is at stake, and c) they have 48 hours to achieve their mission, I couldn’t muster up enough enthusiasm for the flicks any more.

And the market seemed to agree. Besson’s own GSU film, Lockout, never did anything. The recent Kevin Costner flick, 3 Days to Kill, didn’t do well. All of Crank’s 24-hour man-on-a-mission cousins didn’t do well. And then of course there are all the scripts I’ve seen that no one at the studio level will touch anymore. “It’s Taken on a [insert noun here]” can kill a meeting if you read the room wrong. I was even thinking of writing an article about how the GSU model needed to evolve to survive this change.

And then Lucy shows up, the very embodiment of the simplistic GSU model, and kicks ass. A female mule has an experimental drug leaking into her system, making her smarter and smarter by the minute. She’s got 48 hours before it kills her so she’s got to get to a man who specializes in this sort of thing and transfer to him everything she’s learned before it’s too late.

This straight-forward GSU spec didn’t just do “well,” it fucking blew the competition away, collecting 44 million dollars on a summer weekend with a B-list female carrying the entire movie. That is NOT easy to do.

I don’t know what to make of this. Cause all I saw in the trailers was Scarlett Johansson running around with a gun. To play devil’s advocate, one might say they put a new spin on the action-thriller formula (Lucy becomes in tune with 100% of her brain’s capacity, allowing her to become a “realistic” super-hero). But I’ve seen a ton of that “We only use 10% of our brain” stuff in movies and scripts over the past decade. “Wanted” did it. “Limitless” did it. I thought it was old hat.

Maybe Lucy just lucked out and opened on the perfect weekend, when she had ZERO competition (note to Hollywood, if you want zero competition, find the weekend Brett Ratner’s movie opens). I mean if we’re speaking of ideas that feel played out, look no further than Hercules. Didn’t they just make a Hercules movie earlier this year? This isn’t the 50s.

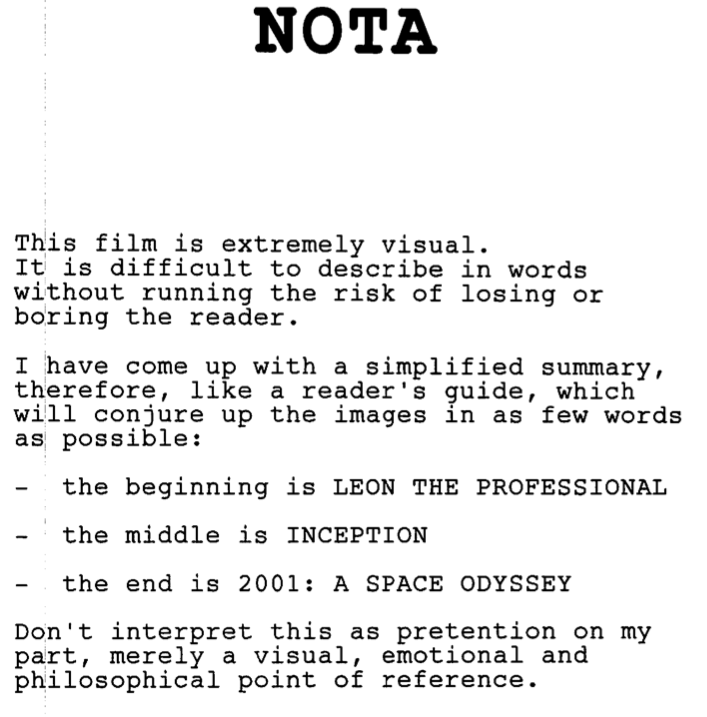

I give it to Besson. He writes fun scripts. And when I say “fun,” I really mean it! “Lucy” was written in comic sans! That’s a first for a professional script. It also opened with this after its title page:

I don’t think you can get away with this if you’re an amateur. People would laugh at you for being presumptuous. But since Besson has a track record, it’s allowed. And I have to admit, it worked. I was using those films for reference while I was reading, so I could picture how this would look. It’s too bad amateurs can’t do this because being able to explain the style in which you hope your movie will be shot can be the difference between two totally different movies in the reader’s head.

As for the story itself, it’s typical Besson. Once we get to the action, we don’t stop. And with Lucy, we get to the action immediately. A sketchy guy convinces his one-night stand, Lucy, to go deliver a suitcase to someone named “Mr. Wang” for him. Why anyone would deliver a mysterious suitcase to a guy named “Mr. Wang” for someone they just met last night is beyond me. But Lucy does it.

That leads to her finding out some super-heroin-crack is in the suitcase. Mr. Wang makes her mule it to Los Angeles, but the packet inside her starts leaking, and whatever this stuff is, it starts unleashing a chemical that opens up your brain, turning you into an exponential Einstein.

At first Lucy just thinks clearer. But then she starts seeing the vibrations around people, which allows her to read their minds. She can use satellites to see through the internet bringing her into offices halfway around the world, using the vibrations of the matter in those offices to literally see what’s happening in them. Soon she’s manipulating matter, so she can “use the force,” picking objects up and putting them down without ever touching them.

It’s all pretty cool stuff. But this is the reason I thought these movies were dead. With so much centered around the action and the gimmickry, we don’t ever get to know anybody. Personally, I loved how they took their time in Taken. It’s one of the reasons I think that film is the standard for the straight-forward simplistic action-thriller. We actually got to know the dad and the daughter before she was captured, and therefore we CARED about him saving her.

I knew very little about Lucy when she was kidnapped and learned only slightly more over the course of the film. That’s why a film like this gets 57% on Rotten Tomatoes. The critics go there and they see a film that feels fun, that feels visual and kinetic, exactly what a film is supposed to be. But because they don’t ever get to know any of the characters, they leave feeling empty, like what they just saw was a dream.

That’s exactly how I felt after reading this. I was like, “Hmm, this would be a fun movie to watch.” But halfway through this review and I was already forgetting what happened.

Comic Sans font! The future of screenwriting??

Ironically, Besson didn’t even nail the GSU model. I wasn’t sure what Lucy’s main goal was for most of the second act (it turned out to be getting to Professor Morgan Freeman to tell him about her discoveries before she died). That felt like a weak goal. Who cares if she gets this information to Red or not? What happens if she doesn’t? Nothing. That’s the very definition of no stakes.

I honestly didn’t expect this to make more than 30 million dollars in its entire run. But I learned something here. One of the most common pieces of advice screenwriters receive is to find a fresh “TWIST” on a tried-and-true genre. It’s the key to your script being “familiar but different.”

Here’s what nobody talks about though. Is how MUCH of a twist you need. Because if it’s not enough of a twist, then it feels exactly like the genre you’re trying to update. If it’s too much of a twist, it’s no longer within the genre’s target zone and feels eccentric. Nobody really knows where that twist range begins and where it ends.

I thought for sure the whole “10% of your brain” thing wasn’t enough of a twist. But I was wrong. It turns out Besson squeaked it in just past the minimum threshold. I wish I could tell you where that range is, but it’s one of those things that can’t be quantified. This is where craft is thrown out the window and artistry takes center stage. It’s up to you to decide how far you should go. If you nail it and fall right smack dab in the center of that range, you’re golden. If not, that’s probably why you’re not getting enough read requests.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: One way to mix up GSU is to start your script with a mystery or two. So instead of jumping into the goal immediately, use the first act to create a “mystery” storyline where the reader’s trying to figure out what’s going on. Then, at the end of the first act, institute the main goal that will drive the rest of the story. So here, we start with the mystery of “What’s in the suitcase?” This leads to a second mystery. Lucy is knocked out by the goons and wakes up with a surgical scar on her stomach. What’s happened to her? She finds out that she’s being used as a mule. Once this mystery is over, she has her goal. Find the other mules before their cargo is transferred, then get to the professor to give him the knowledge she’s gained before she dies. Like I said before, the goal that drives this story is pretty weak, but the use of mysteries at the outset was well done, and pulled us into the story right away.