Genre: Dark Comedy

Premise: A man loses his wife to a car crash and then loses himself. The only person who can save him is a marijuana addicted candy bar vending machine customer service rep who’s too anxious to meet him in person.

About: This script was on the 2007 Black List and forgotten until last year when Jean-Marc Vallee, the director of Dallas Buyer’s Club, read the script and wanted to direct it for his next project. Here are his thoughts: “Demolition is such a powerful and touching story, written with a strong and sincere desire to try to understand the human psyche, what makes us so unique, so special, what makes us love. This is a script of a rare quality, of a beautiful humanity.” Wow, how could you not want to read the script after that? Now with all that being said, Vallee is one of the most sought after directors in town after Dallas Buyer’s Club’s double-Oscar win, so I don’t know if this is still in his plans. I know his next film is with Reese Witherspoon, the adaptation of the non-fiction phenomenon, “Wild.” But I’m not sure if that was the film he replaced Demolition with or one he was doing when he decided Demolition would be next. Writer Bryan Sipe has been writing and directing small indie movies for over a decade, still looking for that first major writing credit.

Writer: Bryan Sipe

Details: 113 pages

Keanu for Davis? He looks like Davis here.

Keanu for Davis? He looks like Davis here.

I was eyeing up spec sale 40,000 Man, the Six Million Dollar Man spoof about a guy who’s built by the government on a budget, knowing it was going to be a really breezy read and therefore an easy review. But I realized that when you read 40,000 Man, you’re getting exactly what you think you’re getting. There are no surprises there. That’s a boring read and a boring write-up.

So I decided on Demolition instead. After I read Vallee’s endorsement, I felt this could be one of those sleeper scripts. I always pay close attention to when a director loves a script because directors are what make the business go round. All the good actors are desperate to work with the good directors, so these are the guys you need to impress to get a script greenlit.

Demolition’s director catnip was all the little dream cutaways. For example, our main character would be looking at everybody walking around the airport and, via voice over, wonder what all their luggage would look like if it was all dumped into one big pile. And so we’d jump-cut to that pile.

Then he’d wonder what it would be like to hold one of the military guard’s guns. And then to shoot a fleeing terrorist. And we’d see that. Directors LOVE this kind of shit. Because it’s visual. It’s something they can show off with. You can’t do that with a straight-forward script. And that’s what sets Demolition apart from its competition. It’s not a straight-forward script.

38 year-old Davis Mitchell is absent-mindedly listening to his wife yap away while she drives them to work, when all of a sudden a car crashes into them. Davis walks away with a few scratches. His wife, however, dies.

Later in the hospital, Davis tries to use the vending machine, only to have the candy bar get caught in the metal thing. After the hospital refuses to help, Davis sends a letter to the vending machine’s customer service division, expressing his desire for a refund. But what starts as a “You owe me 75 cents” letter turns into a series of long confessionals about how he never loved his wife and how he has no idea what to do with his life anymore.

The customer service rep who receives these letters is Karen, a pot-addict with anxiety issues and a 17 year-old son who uses M-80 firecrackers to drive home his point during oral presentations at school. He’s pretty fucked up too.

Karen falls in love with Davis’s letters, and by association falls in love with Davis. She starts to follow him around town, eventually calling him, but avoiding a meeting. They get to know each other on the phone, finally meet, and Davis is enamored with her. So he starts stalking her back, eventually showing up at her house, and oh yeah, she forgot to tell him, she’s engaged.

The two keep seeing each other anyway, because they’re drawn to one another’s self-destructive nature. During this time, Davis creates an unhealthy desire to demolish things. Doesn’t matter if it’s an espresso machine, a vase, or his own house. He seemingly needs to destroy whatever he comes across.

As his professional and personal life implode, Davis must figure out why to keep going, now that his life doesn’t have structure anymore. The biggest question of all is, will Karen be a part of that new life?

So yesterday I saw Leonardo Dicaprio sign onto yet another book adaptation. And I can’t help asking, why do these big actors keep choosing these book adaptations over spec screenplays? It’s not always because the books have built-in audiences. I doubt The Reverent has sold a hundred thousand copies.

The more I look into it, the more I realize it’s because in a book, you can be right there in a character’s head with him. That kind of access moves people in a way scripts have a hard time doing. In scripts, you can only develop character through choices, actions, and interactions. You don’t have that first-person advantage a book does. And when Leo signs onto a project like this, I think he’s playing that big thick character whose head he jumped into in the book. I don’t think he’s playing that thin little guy you see in the screenplay.

But! There’s hope! There is one tool left for us screenwriters, one that brings the audience just as close as a first person novel does. It’s called “voice over.” Now voice over gets a bad rap, but if you look back at a lot of the movies you love, you’ll see a lot of voice over, whether it be The Shawshank Redemption or Taxi Driver (or really any of Scorcese’s films). By getting in that character’s head, we feel like we know them in a way that no “choice” or “action” or “interaction” can give us.

BUT, I still think straight up voice over is lazy. The good writers find a way to do it cleverly, or at the very least, motivate it. That’s what I loved about Demolition. Sipe uses this whole “write a letter to the vending machine company” as a way to get into Davis’s head. It starts off as him wanting his money back, but soon he’s able to dish on his whole life. And we don’t question it. The setup for the letters was so fun and believable (he’s gone a little nuts after his wife died) that we go with it.

But what really sets Demolition apart is it’s a different kind of love story, which is exactly why Silver Linings Playbook did so well. This is what writers don’t do enough of. They don’t give us new takes. They simply re-hash old takes. Demolition is not an old take.

Another thing you’re stuck with when you’re writing these “love story” scripts, whether they be drama, comedy, or whatever, is that things can get boring between the characters quickly. With only two people, there are only so many conversations you can give them to keep us interested. So it takes a good writer to figure out other ways to keep us engaged. Sipe did a really good job of this.

First, he kept our romantic leads away from each other for awhile. You have to tease the audience. The first few times these guys talk, it’s on the phone only. Karen is too scared to meet him.

Then, Sipe created a couple of mysteries. There’s a mysterious car that keeps following Davis around everywhere. Also, Karen keeps promising to tell Davis something she’s never told anyone before. These are carrots you’re dangling in front of your audience to keep them reading. If done well, we will want to eat those carrots.

Finally, he added an extra relationship. Again, if it were only Davis and Karen, we’d be bored, so Sipe gave us Karen’s teenage son, Chris, as well. He and Davis begin a rocky friendship that plays into their development as the script goes on.

Demolition was an unexpected treat, a sort of cross between Silver Linings Playbook and American Beauty. If you like non-traditional love stories with fucked up characters taking center stage, this one is for you.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[xx] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Feelings that are the OPPOSITE of what the character is supposed to be feeling are usually more interesting than feelings that are exactly what a character is supposed to be feeling. Think about it. If a woman loses her husband in a car crash and can’t stop crying, it’s both expected and, if done poorly, melodramatic. But if she has no reaction. Or if she seems happy about it? That throws us off and tends to make us curious. We want to figure out what’s going on with this character and why she would act this way.

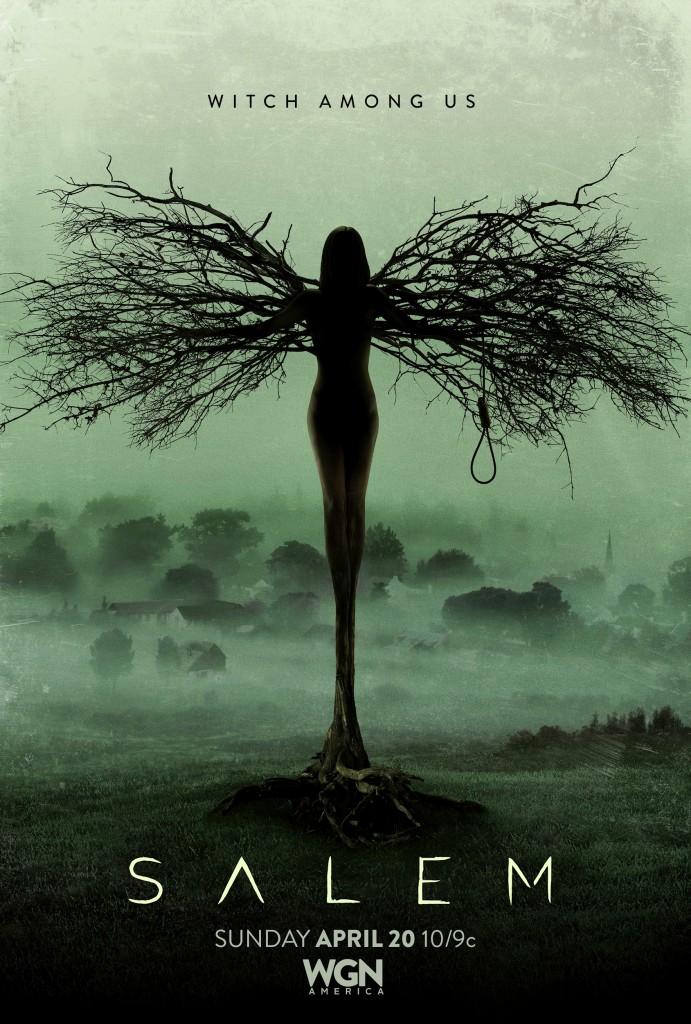

Genre: TV Pilot (Horror)

Premise: (from network) Set in the volatile world of 17th century Massachusetts, ‘Salem’ explores what really fueled the town’s infamous witch trials and dares to uncover the dark, supernatural truth hiding behind the veil of this infamous period in American history. In Salem, witches are real, but they are not who or what they seem.

About: When you think about cutting edge television, WGN America probably isn’t the first channel that comes to mind. But that’s only because they’ve never had an original television show to TRY and become cutting edge with! Enter Brannon Braga & Adam Simon’s new pilot, Malice (now known as “Salem”). You might have heard Braga’s name before. He’s made many geeks happy writing on shows like 24, Star Trek: The Next Generation, and the short lived but cool Flashforward. Co-writer Adam Simon, who’s been writing for over 30 years (his first credit was 1990’s “Brain Dead”) is best known for writing the 2009 film, “The Haunting in Connecticut.” Salem debuts this Sunday.

Writers: Brannon Braga & Adam Simon

Details: 61 pages (May 2, 2013 draft)

Only two more episodes left of Breaking Bad. I’m trying to extend them out as long as possible because I don’t want it to be over. After that, I’m not sure where I’ll head on the TV landscape. I watched one season of Mad Men, which I liked but didn’t love. I was thinking of getting back into it but people don’t seem to be too excited about it anymore.

I liked The Walking Dead, but also left off somewhere in Season 2. That’s probably the leading contender since the show only seems to be getting bigger and bigger. There’s also Game of Thrones. I watched 5 episodes of that and, I’ll be honest, became pretty impatient with the format (lots of talk talk talk talk talk scenes, which would be fine… if your story didn’t occur in a land of dragons and blue people). It seems like it’s a big universe to set up though, and appears to be the show with the biggest number of payoffs (I feel like every month I’m reading about another huge shocker on the show). So maybe I’ll hitch a ride on a dragon and become a Throner (is that what you call yourselves?). What do you guys think I should watch?

Maybe Salem can become my new watch-fest. Yeah, it’s on WGN America, which has never had an original show before, but here’s how I see it. If you’re the first ever show on a network, they’re going to let you go nuts. These execs know that the way you get noticed in TV these days isn’t to do what everyone else is doing. It’s to do something different. So let’s see what kind of show we’re gonna get.

Although the writers never tell us what year it is (tsk tsk writers), I did some online research to find out that the Salem Witch Trials occurred in the 1690s, in Salem, Massachusetts. When your reader has to do your research for you, that usually makes said reader angry.

After getting over that, I was introduced to our hero, John Alden. 16 year old Alden is in love with 16 year old Mary, but unfortunately has to head off to war. That’s one of the great story options you have whenever you’re writing a period piece. You can always write in some war that your hero has to go off to.

This, of course, means your hero will come back, older and wiser, to a place that has changed a lot, which is exactly what’s happened to Salem. Alden is now 27, thought to be a casualty of war, but pops back in to his old haunt, only to find three bodies hanging just outside the town. Apparently, since he left, his town has been overrun by witches. They’ve even brought over an English heavyweight to get rid of them, a witch-expert by the name of Cotton Mather.

Alden doesn’t believe in witchcraft, and yells at anyone who tells him otherwise. All he cares about is finding Mary again. But that turns into an unwanted surprise. Mary has gone off and married Old Man Sibley, a guy Alden and Mary used to despise as children.

The good news is she clearly still holds a candle for Alden. So we’re hoping these two are going to make it happen. Excccccc-cept we learn that Mary’s holding a little secret from her former lover. Turns out Mary’s a witch. She’s so evil, in fact, that she’s cast a spell on her husband so that he’s a prisoner in his own body, a slobbering vegetable.

Eventually, Alden comes to realize that maybe this witchcraft stuff isn’t so ridiculous after all, and goes to Cotton to see how he can help stop them. Cotton tells him this won’t be as simple as a few hangings. This is going to be a long drawn out war. A war that the witches will do anything to win.

Salem was pretty good. I noticed something immediately that I didn’t see from yesterday’s film. If you read that review, I commented that, in horror, you need at least one super memorable scene, something that freaks people out, the kind of thing you can imagine people talking about afterwards.

Remember, in this day and age, with social media and the good old fashioned internet, word of mouth is as powerful as ever. If you can come up with something that chills people, freaks them out, or unnerves them, everyone’s going to be talking about it, and that means more people are going to watch your movie (or your show).

Oculus didn’t have a single scene like that. Salem had three. The first was when Mary, as a pregnant 16 year old, has an abortion, with her servant literally reaching her hand inside her and pulling out the fetus. It was terribly uncomfortable. But it was MEMORABLE.

Next, there’s a scene where a young teenaged girl who is thought to be a witch is tied down and shaved. Every single inch of her is shaved, and one of the men watching this finds himself getting inadvertently aroused. It’s disgusting and sick. But it’s MEMORABLE.

Finally, there’s a huge orgy that occurs with all the witches in the forest, wearing animal heads, and covered in a strange moss-like grimy substance that seems to enhance all the slipping and sliding and pleasure for everyone involved. It’s disarming. But it’s MEMORABLE.

If you’re going to do horror these days, you have to push the envelope a little bit. You have to freak us out. It’s almost like you want whoever reads the script to say, “Are they really going to film this?” That’s when you know you’re pushing the envelope. Salem had that.

There’s something else I’m catching on to in a lot of these pilots I’m reading. There’s usually a character who starts out one way and ends up another by the end of the pilot. I’m not talking about a character overcoming his flaw, like you’d see in a movie (a man who’s selfish learns to be selfless), but rather their beliefs change or our perceptions of them change because of new information.

So here we have Alden, who doesn’t believe in witches. But by the end, he realizes they’re real. There’s Cotton, who we see as bad since he’s killing witches, when we know there are no such thing as witches. But then we learn that witches are real, and all of a sudden, Cotton becomes a guy fighting a just cause. Then there’s Mary. She starts out as the perfect little princess of our story, but then turns out to be a witch.

So when you’re writing these pilots, make sure characters are changing (or our perception of them is changing) during the course of the story.

Finally, probably the hardest thing to do with a pilot like this (something steeped in history and lore) is to pack all that mythology in there. It has to feel like its bursting with possibilities. Think of it like a dinner. Too many amateur pilots I read feel like they ate a couple of sushi rolls and a piece of celery. Your pilot should feel like a five-course Thanksgiving meal. Like its belly is full – that it can’t even eat one more mint. Braga and Simon clearly did a great job researching and filling this world up as there arose details around every corner. It reminded me a lot of Travis Beachem’s “Killing on Carnival Row” in that sense.

Unfortunately, whenever you’re doing a show like this, you’re only as good as your budget. Once Upon A Time had big ambitions but its budget made it look like it was 1982 again. So I don’t know if WGN America will be able to show off this rich complex period world Braga and Simon have created. But if they do it justice, they should have a good show on their hands.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Don’t be afraid to make one of your main characters a “bad guy.” I think as writers, we often want to protect our characters. Particularly our main characters. We want them to be good and just. But Salem taught me that it’s usually more interesting if you make one of those main characters “bad.” I thought Mary was going to be a typical unattainable romantic interest as she had married the town leader while Alden was gone. That might’ve worked out okay. When we found out Mary was a witch though, now her character takes on a whole new meaning and is far more fascinating.

Genre: Horror

Premise: A woman tries to exonerate her brother, who was convicted of murder, by proving that the crime was committed by a supernatural mirror.

About: Oculus is the newest movie from horror kingpin, Blumhouse Productions. Everyone who made the film (writers and directors) are fairly new to the business. The film came out in theaters this weekend and finished third at the box office, with around 12 million dollars (behind Captain America and Rio 2). Coolest thing about Oculus? Definitely not the movie itself. But rather Rory Cochrane, who played the iconic Ron Slater in the classic Dazed and Confused, starred as the father in the film.

Writers: Mike Flanagan and Jeff Howard (based on a short screenplay by Mike Flanagan and Jeff Seidman)

Details: 105 minutes

Blumhouse is an interesting story. For a long time in Hollywood, people were making 20-40 million dollar horror films. If you were lucky, those films would make 70 million at the box office, and then some more money on DVD. Blumhouse came in and said, “There’s gotta be a better way to do this.”

How? Well, scaring people doesn’t take a big budget. It just takes a good concept and a smart script. So they started making these movies budgeted at under 5 million dollars, that were still getting those 70 million dollar box office returns (or more!). All of a sudden your profit was 65 milllion dollars instead of 30. Paranormal Activity, Insidious, The Purge, Sinister are a few of the films that have benefited from this model.

This approach really shook the industry up. Why make big-budget horror movies anymore? We can just give Blumhouse a few million bucks and print money. Blumhouse might as well of called itself Powerhouse.

That is until today. Today, Blumhouse proved why its model is imperfect, exposing a big challenge in writing these kinds of films. I’ll get to that in a sec. But for those who didn’t see the film this weekend, here’s a recap.

Oculus follows a brother and a sister who experienced one hell of a shitty childhood together. When Kaylie and Tim were young, their father (whose job is still a mystery to me) worked in his office at home, where (for reasons that are still a mystery to me) he’s purchased a really really really old mirror that doesn’t go with the rest of the office at all.

Kaylie and Tim watch as this mirror starts to possess their father, which in turn drives their mother mad. In order to save himself and his sister, little Tim is forced to kill his dad at just 10 years old. But that’s not the main storyline. The main storyline actually takes place 11 years later, with Tim finally being released from the mental institution he’s been rehabilitated at, as he is now deemed fit for society.

When he meets up with his sister for the first time in forever, he thinks they’re going to go bowling or grab a big mac or something. Instead, she tells him they’re fulfilling their promise from when they were kids – to destroy the mirror that possessed their dad.

Tim is shocked to find that Kaylie still owns their parents’ house after all this time (which makes zero real-world sense, of course), and actually HAS THE MIRROR. She’s set up a bunch of monitoring equipment throughout the house so she can document what happens and prove the truth – that the mirror possessed their dad and made him crazy.

The problem is, during the past 11 years, Tim has been brainwashed by the world’s best psychiatrists, who’ve told him that everything he experienced in that house was his imagination. That the mirror wasn’t evil or possessed at all. Tim was just a deranged boy. So Tim is trying to convince Kaylie that she’s nuts.

While all of this is happening, flashbacks are inserted to show us just what happened with Dad and the mirror that fateful summer. We already know he and the mom were killed, but the writers want us to know how. And therefore, we get a sort of dual-storyline, 60% present, 40% past, which all takes place in this house, with this mirror.

Rory Cochrane in Dazed and Confused!

Rory Cochrane in Dazed and Confused!

What is the worst mistake a horror movie can make?

Anyone?

Anyone?

NOT BEING SCARY.

Oculus is a horror movie and it isn’t even scary! It’s just two young adults talking to each other for 90 minutes. When you write a horror movie, scary needs to be a given. On top of that, scary movies need that one huge super memorable scary freaking moment that you know audiences will be talking about afterwards. In The Ring it’s when the girl climbs out of the TV (amongst other things). In The Exorcist, it’s when the girl’s head spins around. In Rosemary’s Baby, it’s the rape dream. What is it here?

It’s not even that it didn’t have this scene that bothered me. It’s that it DIDN’T EVEN TRY TO HAVE ONE. There wasn’t even an attempt. It was all just a bunch of talking and dumb jump scares.

But anyway, here’s the problem when you try to make the 5 million dollar horror movie. When you make the 5 million dollar horror movie, you have to limit your locations heavily. You usually get one big location, maybe a few early outside shots to imply a bigger world, and that’s it.

So if you look at all of the Blumhouse movies, they almost all take place exclusively at one home. Now if you have a solid premise, like, say, The Purge, this can work. But when your premise is thin, you’re screwed. You’re already making it tough on yourself by giving an audience only 5 rooms to spend the entire movie in. Now you tell them that you don’t have much to do in those rooms??

I have no idea how Oculus was approached as a story, but I can take a guess. They had this idea of this brother and sister and a mirror in a house, and as they started to construct a plot around it, they realized they didn’t have enough story. Again, this is the danger you run into with the Blumhouse approach. One location = only so many story options.

So they said, “Hmm, we need to add more story somewhere.” And that’s when someone came up with the brilliant idea: “Why don’t we spend half the movie in flashbacks seeing what happened to the family when the kids were younger?”

As soon as I picked up on that, I knew the story was dead. If you’re spending that much time in the past, it means you don’t have enough of a story for the present. Think about it. We didn’t need a SINGLE flashback for this story to work. We would’ve always understood what was going on in the present without it. So what was the point of adding it? The only logical answer is “to fill up space.”

You never want to only FILL UP SPACE when writing a script. A story should feel like it’s bursting with possibilities, like there isn’t enough time to tell it all. I guarantee you, if you’re using flashbacks to elongate your story, the audience will feel it, and they’ll start getting bored, which is exactly what happened here.

I’m not sure if this exposed the Blumhouse model for the house of cards it is, or if we’ve just reiterated something we’ve known about screenwriting forever: A weak concept will always result in a weak script. I mean WHAT IS THIS ABOUT??? A mirror that sort of possesses people (but maybe not) and also makes people imagine things?? So two people try to “kill it?” Are you kidding me?? Throw if off a cliff. Story over.

Here’s another way to easily tell if a script is going to suck: One of the characters spends TEN CONSECUTIVE MINUTES talking to another character with nothing but exposition (as Kaylie does to Tim when they come back to the house). There are only two possibilities for why anyone would do this. One, they’re not a good enough writer to know how to hide exposition. Or two, they’re trying to add as many pages as possible to get to the minimum run time for a feature. Neither scenario ever results in anything good.

Anyway, this script, at least when it’s watched as a film, is really bad. It’s one of the more disappointing films I’ve seen in the last calendar year.

[x] what the hell did I just watch?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the price of admission

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Screenwriting 101 – Make use of your premise! This is a script about a mirror. But there were NO MIRROR-RELATED SCENES! Actually, check that. There was one. That didn’t have anything to do with the story (it actually takes place before they even get to the house). It’d be like if you wrote Ghostbusters and there was one ghost. It was baffling. Here’s a tip: If you write a movie like Oculus, and you can substitute ANYTHING for the mirror (a haunted record player, a haunted table, a haunted painting) and it would still be the exact same movie, then you’ve done a terrible job writing that movie.

This is your chance to discuss the week’s amateur scripts, offered originally in the Scriptshadow newsletter. The primary goal for this discussion is to find out which script(s) is the best candidate for a future Amateur Friday review. The secondary goal is to keep things positive in the comments with constructive criticism.

Below are the scripts up for review, along with the download links. Want to receive the scripts early? Head over to the Contact page, e-mail us, and “Opt In” to the newsletter.

Happy reading!

TITLE: LOST IN THE SUPERMARKET

GENRE: Dramedy

LOGLINE: While working part-time in a supermarket, an ordinary college guy tries to save a bipolar jazz genius from self-destructing — but falls for the musician’s girlfriend, and finds himself in the process.

WHY YOU SHOULD READ: This is my third script to make the Nicholl Fellowships quarterfinals (two prior scripts were psychological/supernatural thrillers) and while I have had some success in other contests with different screenplays before, this is my most personal statement about what it means to be an artist, who is struggling against the odds to leave your mark in whatever creative endeavor you choose. It’s about the heartache and joy of doing something you love, regardless of the outcomes.

WHY YOU SHOULD READ: We’ve been pitching THE MAYFLY as, “Children of Men meets Escape From New York,” but the premise is best explained by a single question:

Get Your Script Reviewed On Scriptshadow!: To submit your script for an Amateur Review, send in a PDF of your script, along with the title, genre, logline, and finally, something interesting about yourself and/or your script that you’d like us to post along with the script if reviewed. Use my submission address please: Carsonreeves3@gmail.com. Remember that your script will be posted. If you’re nervous about the effects of a bad review, feel free to use an alias name and/or title. It’s a good idea to resubmit every couple of weeks so your submission stays near the top.

Genre: Crime/Drama

Premise: (from writer) Calvin Barry, lost and adrift in his 20s, falls victim to the charms of Gwen Summers, a seductive young beach bunny. Soon, with the help of Gwen and her stoner roommate Amy, Calvin embarks on a binge of sex, drugs, and violence – a downward spiral he may not be able walk away from…if he even wants to, that is.

About: (from writer) Big fan of ScriptShadow. I’ve been a reader on and off for awhile, and I finally talked myself into submitting a script for Amateur Friday consideration. I’m Caleb Yeaton, a (hopeful) writer from around Chicago. I’ve been writing for a little over fifteen years, although I’m way too cheap to shop my scripts around to contests…which, considering my lack of connections, may be the wrong approach thus far. Anyway, I’m trying to get my current script, California Dream, a little more exposure – it’s been well-received on several workshop sites, and, while those reviews are helpful, I’d love the extensive Amateur Friday treatment. As for why you should read the script? California Dream drags the old-fashioned noir genre into 2014 with style – it’s dark, sometimes unpleasant, occasionally funny, and it’s been fine-tuned over a dozen drafts into a clean, tight story. Not convincing? Okay, there’s also a lot of sex and nudity in it.

Writer: Caleb Yeaton

Details: 103 pages

I don’t know who this is but she looks like she’d be perfect for Gwen.

I don’t know who this is but she looks like she’d be perfect for Gwen.

So I was sitting there with Miss SS after reading California Dream and, like she always does when I finish a script, she inquired, “How was it?” I wasn’t sure what to say. I liked the writing a lot, but this isn’t really my thing. Every reader has their “things,” the genres and types of stories they respond best to, and this didn’t fall into any of my categories. So I was trying to decide if my disinterest in the genre was clouding my judgment on whether this was “worth the read.”

Usually, I know the rating within 10 pages of reading a script, but here it was a different story. Do I give this a bump because I liked the writer? If I heard John Lennon sing for the first time, but the song was mediocre, I’d still tell people to check him out, right? Not that this script was mediocre. It was pretty good. But I may have to make my way through the review before deciding what rating it deserves.

California Dream is about 26 year old Calvin Barry, a lost soul who’s been forced to move back in with his parents in Los Angeles. Desperate for independence, he starts looking for a job, but finds 18 year old hottie Gwen Summers instead. One look at Gwen and you know she’s bad news. But she’s hot bad news, and Calvin, being a young American male, cannot say no to hot bad news.

So Calvin starts hanging out with Gwen and her also hot pot-head bikini-clad roommate Amy. The three indulge in a little drinking, a little drugs, a lot of sex, and a whole lot of robbing. Yup, poor Calvin, whose father is a cop mind you, finds himself accompanying Gwen to her nightly liquor store hold-ups, and it isn’t long before he starts holding the gun.

Greed is a powerful force, however, and pretty soon liquor stores aren’t enough. If they want big money, they have to go after drug dealers. This decision comes with a price though. Calvin accidentally kills one of these dealers during a robbery, and now must face the fact that he’s a murderer. Strangely, the girls don’t seem concerned. They just want to buy more drugs, drink more vodka, and party til sunrise.

Naturally, this all catches up with them. Plenty of these liquor stores have security cameras. However, it’s not the girls the cops focus on. It’s Calvin. So he’ll have to decide whether to get out before it’s too late. Unfortunately, the girls want to do one last major hit. And because they’ve got Calvin wrapped around their finger, what do you think he’s gonna say?

California Dream is sort of like Bonnie and Clyde meets Juno meets Y Tu Mama Tambien meets Wild Things. I believe that’s quite an accurate description, as sometimes “Dream” meets the depths of a “Bonnie and Clyde” or “Y Tu Mama Tambien,” but occasionally flashes the kind of Skinemax scene that reminds you of “Wild Things.”

The Juno comes in with the way the girls talk, specifically Gwen. Here’s the thing when you’re writing female dialogue that’s trying to be witty and raw and clever and current – if you try too hard, it shows. And California Dream skirts that line throughout. Sometimes I was okay with it, but other times it felt like too much. Here’s what I mean: “Mmm. It’s not like we had a fuckin’ choice, you know? We’re besties. Her parentals kicked her to the curb because drugs. Like, not even a warning. Just get the fuck out. She needed help gettin’ a place. I was sick of my stepdad anyway. Dude went all pedobear as soon as I discovered my tits, you know? (shrugs) So, boom. Roommates.”

Unfortunately this is a “feel” thing. As a writer, your job is to ask, “Am I trying too hard here?” If you’re not sure, the answer is probably yes. I understand this dialogue gave Gwen a lot of her personality, and it’s a big part of what makes her so memorable. But I’d probably dial it back some.

There’s a much bigger issue here, however. And that’s our main character, Clyde. You’re almost always going to have a problem when most of the other characters are more interesting than your hero. I’d put Gwen, Amy, Ian (Gwen’s other boyfriend), and Taryn (Clyde’s sister) above Clyde on the interesting level.

It’s not impossible to make this work (Obi-Wan, Han, Chewbacca, Darth Vader, R2-D2, C-3PO and Princess Leia are all more interesting than Luke Skywalker) but it’s really hard. You usually run into this problem when you have a really passive hero, and that’s what I saw here. Clyde doesn’t make any decisions in the script. Everyone else makes them for him. It’s so hard for the reader to connect with someone like that.

There were also a few false moments. One of the things you have to make sure of when you write, is not to let your desire to make a scene work take precedence over it making sense. The scene where Calvin and Gwen meet was an example of this. The scene is designed to have Calvin apply for a fast-food job and Gwen to comment on it (“You don’t wanna work here”) which opens up their first conversation.

But here’s a girl Calvin sees while going into this place, who he clearly finds very attractive. You’re not going to apply for a job at a fast food joint right in front of a super hot girl you’re hoping amongst all hope you’ll get to talk to. It’s embarrassing and it’s love suicide. I’d suggest rewriting this scene. Calvin waits until Gwen leaves THEN asks for the job application. He fills it out, goes outside, Gwen’s sitting right there or by his car and ‘catches’ him. “Getting a job at Biggie’s huh?” Have Calvin lie and say it was for his friend or something, she calls him on it, and the conversation can evolve from there.

On the plus side, this script builds better than any I’ve read in awhile. One of the problems I see with a lot of screenplays is that they build up right away, then fall down early in the second act. They then stagnate for 60 pages, until exploding in the finale. California Dream had this nice steady “slow-build” pace to it, pulling me in more and more as it went on.

In the end, my suggestion to Caleb would be to make Calvin a more active and interesting character. I understand that he has to be lost in order to be pulled in by these girls. But there’s got to be a way you can do that AND make him compelling. And eventually, he has to be active. He can’t let Gwen call the shots the whole way through. He’s got to grow and become a man of his own. And really, that’s what this should be about – a guy who’s finally taking control of life instead of letting life control him.

Very very close. But I’d say this is a smidgen below ‘worth-the-read.’ Still, when Caleb has a tastier premise that’s more up my alley, I will gladly check it out. ☺

Script link: California Dream

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Passive or “Reactive” protagonists usually only work in comedies (40 Year Old Virgin or The Graduate) where they’re constantly getting in a lot of funny situations and making us laugh. Since in any other genre, we won’t be laughing, we’ll start to get frustrated with the lack of drive these characters display.