Search Results for: the wall

A case study in how to create a sympathetic protagonist.

Genre: True Story/Sports

Premise: Set in the 50s, a young orphan girl must rise out of the confines of her orphanage to realize her unparalleled talent in the sport of chess.

About: If we are all looking at the best case scenario for what our proposed screenwriting career looks like, Scott Frank is a great comp. He wrote Get Shorty, Out of Sight, Minority Report, and, most recently, Logan. He’s now teamed up with Allan Scott to adapt the 1984 Walter Tevis novel, The Queen’s Gambit, for Netflix.

Writer (pilot episode): Scott Frank

Details: 60 minutes

Here’s the rule.

If there is a Netflix show or movie that makes it to #1, which then gets dethroned due to some other new Netflix entry, but then makes it BACK to #1? It’s always a great show or movie.

This rule stands until it can be disproven!

That’s exactly what we have today. We have The Queen’s Gambit shooting up to #1 early, getting dethroned by some new Netflix drivel, then charging back to take the top spot again. Check mate, my dear.

Check. Mate.

I didn’t have a lot of interest in this show until I found out Scott Frank was involved (and heard a few of you championing it in the comments section). Frank is a hell of a writer. And now that I’ve seen the pilot, you get a really clear look at what good writing does for a show. Cause everything else at Netflix is so far down the ladder, Queen’s Gambit is looking like Chinatown. If you’re a writer, you’ll definitely want to check it out. Especially if you struggle with writing compelling characters that readers root for.

Beth Harmon is 9 years old when her parents die in a car crash. Beth was in the car too but miraculously survived without a scratch. It’s not clear whether that’s a blessing or a curse. The next thing she knows, she’s thrust into an orphanage that has a pretty good vibe going. Oh, except for the fact that they force their girls to take tranquilizers every day. 1950s America had some radical ideas on how to raise our youth, that’s for sure.

Because Beth is high all the time, she stumbles around the grounds in a spaced out state. But she eventually finds her way to the basement where the janitor, an introspective sad man named Mr. Shaibel, plays chess games against himself. Beth asks him to teach her and while he’s reluctant at first, he soon realizes she has a generational talent for the game.

While Beth struggles to feel emotion after the loss of her parents, it’s clear she enjoys learning the game. Every night before bed, she takes a couple of the tranquilizers she hid, gets high, and envisions a chess board on her ceiling so she can go through all the possible game scenarios. It isn’t long before she’s easily beating Mr. Shaibel. This leads to Shaibel connecting Beth with a chess club friend who works at the high school. That friend asks Beth if she’d like to come play against some new competition. Sure, she says, and promptly beats the school’s ten best players… all at the same time.

Meanwhile, the state suddenly decommissions the use of tranquilizers on children, and Beth is besides herself. She’s come to depend on those pills and now she’s forced to be stone cold sober. Determined to keep her high going, Beth sneaks into the back room where the pills are kept, and jams a large handful of them down her throat. Just as the headmaster reaches the room, Beth OD’s. End of episode.

If there is a super-hack to screenwriting – a singular element that ensures screenplay success – it is a sympathetic protagonist, someone we care about and who we want to see succeed.

If you do that right, it feels to the reader like they know the person. Which means you’ve broken the 4th wall. Of course we want to see them succeed. We feel like we know them!

Unfortunately, the formula for writing that character is elusive. Making your hero funny and giving them a ‘save the cat’ moment will make us care about them, yes. But it’s the degree to which we care about them that matters. If we only “kind of” care, then we’re only “kind of” interested in what happens to them.

And since we’re all so movie savvy, we don’t react well to cliche versions of these constructions. For example, everybody can tell you the reasons why Indiana Jones is [arguably] the most popular movie hero ever. Yet every time someone tries to clone those aspects of his character (charismatic, sarcastic, rebellious, roguish), it doesn’t work.

So how do we create a hero that audiences truly care about? The Queen’s Gambit is a great example of how to pull it off. First, Scott Frank creates a sympathetic situation. Beth loses both of her parents in a car crash. I’m going to come back to that car crash in a minute because I find car crash backstories to be cliche. But Frank does something to make it work which I’ll explain.

In regards to the sympathetic situation of losing your parents, there’s one extra thing you need to do if you want us to really care about that character. Which is this: SHE DOESN’T FEEL SORRY FOR HERSELF. That is so pivotal, I can’t emphasize it enough. Where so many writers get it wrong is they create a character who has experienced trauma or loss… and then they double down and have them feel sorry for themselves. The secret ingredient to creating a sympathetic protagonist through trauma/loss is making sure they don’t lean into that loss and play the victim. We don’t root for those people. I don’t know the science behind it but we just don’t.

And it doesn’t have to be exactly like Beth. Beth isn’t the most joyous person. She’s pretty even keel. But you can have your character be more joyous, depending on the genre and story. The main thing is don’t allow them to be sorry for themselves. We like people who fall down but keep getting up and trying. Not people who fall down and start crying and say they can’t do it anymore.

There’s one more thing you need to do to really kick your character into high gear. It’s not easy to define but I’ll try. You need to introduce one (although more than one is fine) extra element into your character that is offbeat in some way – that takes the character further away from the generic version that everybody else writes. Cause I’ve read a ton of “prodigy” scripts and, trust me, 99% of the time, everybody writes the same prodigy character. You need a mutation if they’re going to feel real.

That comes in The Queen’s Gambit when a fellow orphan asks Beth what the last words her mom said to her were. We then do a brief flashback from within the car, right before it crashes, and the mom says to Beth in a sad defeated tone, “Close your eyes.” Right then we realize the crash wasn’t an accident. It was a full blown murder-suicide attempt.

Before this revelation, it was just another “parents die in a car accident” backstory. But when we see that the mom was actually trying to kill them all, then it becomes a lot more sinister, and creates feelings from the daughter that are way more complicated. A single feeling (sadness) is often boring. But two conflicting feelings (sadness and anger) can ignite a character, since it places them in a constant state of conflict. This was the thing that elevated the character, in my eyes. She truly felt different after that.

In addition to that, Frank does what I tell you guys to do all the time – make unconventional choices throughout your story. Turning your 9 year old heroine into a full-blown drug addict was very much an unexpected choice. And even the orphanage itself – which was a safe and loving place, for the most part – was an unconventional choice, seeing as 9 out of 10 writers would’ve turned the headmistress into Miss Hannigan.

My only issue with the show so far is that it isn’t clear if the drugs help her play chess better or she’s just hooked on them and needs them to feel good. I’ll be disappointed if she needs them in order to play well.

But regardless, I thought this was strong! Nice to see a good show on Netflix again!

[ ] What the hell did I just watch?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[xx] worth the stream

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Is there better actor catnip than the tortured genius? There isn’t an actor in the world who doesn’t want to play that role. So if you’ve got an idea with a tortured genius in it? Go ahead and write it. You’ll have WME, CAA, and UTA kicking down your door to get their client attached.

Well this script sure turned out to be bat#$@% bananas. Get ready for adult fetus mayhem!

Genre: Horror

Premise: A team of military personnel are sent to inspect an abandoned missile silo after a diseased old man emerges from it.

About: S. Craig Zahler! The man. The myth. Zahler’s magnus opus Brigands of Rattleborge is STILL in my top 5. They keep saying they’re going to make it yet it still hasn’t been made. One of these days. I’m not sure when Zahler wrote Silo but I’m surprised nobody’s jumped on it. It’s one of his most marketable ideas. AND it’s actually original. When does that ever happen with horror scripts? I have a feeling this review will renew interest in the script.

Writer: S. Craig Zahler

Details: 112 pages

The other day I decided to celebrate Halloween Candy Week by buying one of those big square packs of single-dose Reeses Peanut Butter Cups. I’m watching the Bears game and I eat one. And then I eat two. And that leads to me eating three and four. Once I get to four, I’m like, why would I stop? At this point I’m covered in a myriad of orange wrappers, brown chocolate holders, and those white cardboard pieces that give the wrapper structure. It was in that moment that I had an out of body experience whereby I looked down at myself covered in this shameful mess of corn syrup debauchery and thought… Why didn’t I buy two of these??

Reeses are the “Dale” of Halloween candy. All other candies can only hope for a few seconds of attention. Sorry if you didn’t get that reference. I promise you it was funny.

Robert Linderman is a 30-something psychiatrist working for the military. He gets a visit from a couple of higher-ups who take him to meet fellow military personnel, Kirstin, Bodell, and Tyler. These three specialize in decommissioning missile silos that the U.S. military doesn’t need anymore. They’re charged with going to silos, taking out the warheads, and closing the place up for good.

Well, this latest job is going to be different. A few days ago, an old man who appeared to be heavily diseased, attacked a woman at a truck stop. That man, it turns out, was thought dead 30 years ago. They’ve traced him back to working at an old missile silo. But here’s the spooky part. The military doesn’t have any records of this silo. Fearing that it might still have active warheads, the team’s mission is to go in there, make sure there’s no one else, and retrieve any warheads.

They’ll be accompanied by Captain Gonnersnson, a man they will later find out is an absolute psycho who shouldn’t be in charge of anything. They head to the silo, go inside, but are immediately met with a wall that’s been welded closed with all sorts of random junk. Whatever’s going on in this silo, it looks like someone (the military??) made sure it could never get out.

The team go down several staircases and hallways until they finally reach the main room. It’s there where they find the first bodies. Mostly military people who have committed suicide. Except for one room where a naked woman has been hanged and, below her, 5 men have been laid out, naked from the waist down, and shot dead. Above the woman’s head, someone’s written, “Traitor.”

The next room they check, there are three old men. Who are alive! They come at our group, trying to grab at them. Our team shoots them dead. Yay for guns. The guys begin to put together the puzzle. Some sort of radiation leak happened here 30 years ago. Instead of exposing the story, the military decided to lock everyone in here and wait for them to die. Except they didn’t die. All of this resulted in something unheard of. Twin fetuses… that grew into a psychotic adult fetus coupling. Try that on at your next Halloween party!

You know you’re reading an S. Craig Zahler script when you encounter the line, “We found the skull of a rat in his feces.”

First, I want to commend Zahler on a cool idea. How many zombie scripts have you read that felt, oh, I don’t know, just like all the other zombie scripts you read!? A lot, right? Silo goes to show that if you can come up with an interesting location (a missile silo), even if it’s in a familiar genre, you can give people something they’ve never seen before.

Zahler isn’t afraid to take chances in his execution either. Once we got deeper into the silo, we started hearing voices. Voices that only some of the characters were able to hear. I was thinking, “Aren’t we getting off track here? Let’s stick with the genre we’ve set up.” But then I remembered, this is EXACTLY what you need to do to stand out in a popular genre. You have to take chances. Do weird stuff. That’s why Hereditary was a hit with so many people.

But Zahler’s got Ari Aster beat on the weirdo front. He creates a fetus that has, assumingly, continued to grow even after it was out of the body, due to all the radiation madness in the silo. This created an adult fetus (that’s actually twins and still talks like a child) that was running the silo. I mean… not to say ‘mic drop,’ but Ari? You better bring the crazy in your next movie if you want to stay on Zahler’s level.

Another thing I like about Zahler is that he’s not afraid to build up to something. A lot of writers get impatient in this genre. They feel like they need to hit you with a big scare every few pages. If they don’t, you’ll stop reading. Zahler doesn’t have that worry. He’ll take his time getting to a set piece. He’s able to do this for a couple of reasons. One, there’s a sophistication to his writing that makes you trust him. I’ve read a lot of unsophisticated writing and if a writer can’t even make a sentence work, why would I assume that if I stick around fifteen more pages, he’s going to make something interesting happen?

And two, he knows how to build to a moment. Characters are active and moving towards the next goal at all times. We’re getting little clues (a bunch of large furless rats) that something is amiss. Each time we go down a new hallway, it gets a little darker. Every time we go down a new stairway, we hear another strange sound. There’s purpose to Zahler’s sequences that let you know, at the end of the sequence, you’ll be rewarded. If you can do it this way, do it this way. It’s much better than throwing an endless array of scares at the reader. It’s only a matter of time before that scare-a-minute approach stops having an effect.

But the truth is, this is just a cool idea. My feeling with cool ideas is that they do a lot of the work for you. Which means lots of writers could’ve made this work. Zahler’s just got that extra crazy gear he can go to. I’m still not sure what I think about grown twin fetus guys. That may have been a bridge too far for moi. But I’m not telling you it isn’t original. That’s for sure.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Let me tell you the one particularly genius angle Zahler came up with that got me: The military wasn’t aware of this missile silo. I thought that was so cool! 99 out of 100 writers would’ve had the military aware of it. By making it unknown to the military itself, it made the mystery of what this place was that much deeper, that much cooler. Always be looking for that one extra angle that elevates your idea. This was it for me.

In my attempts to finish all the Last Great Screenplay Contest entries by my target date of October 31st, I’ve found myself reading a lot of bad dialogue lately. But not normal bad. Bad in a specific way. A lot of the dialogue I read in amateur work is STILTED. There’s no life to it. It reads rote, logical, robotic.

Which makes sense if you understand screenwriting.

When a writer goes into a dialogue scene, they often have a preconceived notion of how the dialogue is going to go. For example, if Margaret and her husband, Darryl, need to discuss selling the house, you have a sense of what that conversation is going to look like before you’ve written it. Therefore, the dialogue is just a matter of dictation. You place down on the page what’s in your head. “We need to get the house up on the MLS before the end of the month.” “I know.” “Well, then we need to take pictures.” “We have pictures.” “The ones that Joan took? She took those on her iPhone. We need professional pictures.”

Notice how this is logical information being exchanged (and bland information at that). There’s a reason for that. As a writer, you see the scene BEFORE IT’S HAPPENED. But real people experience moments AS THEY’RE HAPPENING. This fundamentally changes how words come out of peoples’ mouths.

As a writer, all you’re thinking about is conveying the information properly so you can get from point A to point B. As such, your dialogue will reflect this. It will almost feel like Character B knows what Character A is going to say before he says it. And that’s because she does. You, the writer, are Character A and B so you’re subconsciously setting up questions and answers that the other character already knows.

Meanwhile, in real life, Character A doesn’t know what Character B is going to say. They might have an idea. But they don’t know exactly what they’re going to say. This is why real-life conversation tends to have more energy than movie dialogue. It’s alive. It’s evolving second by second. Therefore, you want to try and capture truthful exchange in your dialogue by any means possible.

One of the ways to do this is through a “free dialogue pass.” This is where you erase all of the artificial motivations that you, the writer, are imposing on the scene, and think of the scene more as how it would occur in real life. In other words, Character A doesn’t need an overt goal going into the scene. There shouldn’t be any time restriction on the scene (most dialogue scenes are about 2 and a half pages long. You’d get rid of that). And, most importantly, don’t have any preconceived notions about what the characters need to say to each other or where the scene needs to go. It’s going to go WHEREVER THE CHARACTERS TAKE IT. That’s a scary thought for a lot of writers. They want to control what the characters say. But your need to control the dialogue is what’s resulting in it being so stilted. I mean, when has anything that’s overtly controlled ended up feeling natural?

Your “free dialogue pass” can last as long as you want it to. It can last 20 pages. The idea is to get a natural flow of dialogue that you can then mold into something more structured. If you find a six-line exchange between two characters that’s really clever in your “free dialogue pass,” and that’s the only part of the exercise that makes it into the final scene? That’s a win. Because the other option is only having the boring structured exchange of information that comes from controlled dialogue.

In order to get the most out of this exercise, I want you to understand just how many options are open to you when Character A says something to Character B. Because I think that most writers believe there are only a couple of responses. And, usually, those responses are responses they’ve seen characters say in other movies. If you really want your dialogue to feel fresh, you need to open your mind to the fact that there are thousands of potential responses to every line of dialogue. And if you’re only going with the two or three most obvious ones, I got bad news. Readers think your dialogue sucks. You need to get out of your comfort zone. You need to take more chances.

So, I’m going to give you a single line of dialogue. Character A says to Character B, “What’s your favorite color?” Okay. Now. What’s the first response that comes to mind for that question? Well, let’s see just how many ways another character can respond to this.

1 – The character can simply answer the question. “Blue.” This is usually the least interesting answer.

2 – They can reject the question. “None of your business.”

3 – They can respond with a question of their own. “What if I like more than one?”

4 – They can ignore the rules. “Blue, Yellow, Aqua Green, and the Rainbow.”

5 – They can flirt. “The color of your eyes.”

6 – They can flirt better. “That’s personal information you’re requesting. What do I get if I tell you?”

7 – They can choose not to answer at all.

8 – They can lie. “Orange.” (Knowing that the other person’s favorite color is orange)

9 – They can make an assumption about why the other character is asking the question. “Ooh, are you psychologically evaluating me? You want to know my sign next?”

10 – They can call the other person out. “Really? That’s the best question you can come up with?”

11 – They can answer with a song. “Blue mooooooooon. You saw me standing alooooone.”

12 – They can get irrationally upset. “Why the f%#@ would you ask me that?”

13 – They can be playful. “Well that’s offensive.” “Why?” “Cause I’m colorblind.”

14 – They can make a demand. “You tell me first.”

15 – They can tell a story that leads to their answer. “Earlier this year I was driving up PCH at sunset and it had just rained. The clouds were parting right as the sun was setting and it caused this filtered orange-purple glow to settle over the coast for all of 30 seconds. It was the most beautiful thing I’ve ever seen. Whatever that color was? That’s my favorite color.”

16 – They can make a joke. “The color of money, of course.”

17 – They can be preoccupied with something else. “Did I leave my wallet in the car?”

18 – They can misunderstand. “Your favorite color? Why would I know your favorite color?” “No, YOUR favorite color.”

19 – They can opt out of the conversation. “Can we talk about something else?”

20 – They can become Movie Trailer Voice Guy. “IN A WORLD OF ENDLESS COLOR, ONE WOMAN MUST KNOW HER DATE’S FAVORITE FOR SOME REASON.”

The idea here is to break out of the logical thinking trap that is required to map out a screenplay. We’re often in “structure” mode when screenwriting and that’s the last place you want to be with dialogue. Allow yourself to be free. And when you’re inside of those scenes, stay away from common answers. Dialogue tends to get the most interesting when something unexpected is said. I’ll give you the perfect example because it happened last night on The Bachelorette.

It’s early on in the season so the Bachelorette, Clare, doesn’t know anybody yet and one of the guys, Brandon, sits down with her for the first time. These carefully orchestrated sit-downs are usually boring because the conversations are decided upon ahead of time. So I was falling asleep, not really paying attention. Then Clare asks, “So why did you want to meet me?” And Brandon says, in a completely sweet and innocent manner, blushing as he says it, “Well, I thought you were gorgeous.” And there’s this pause before Clare’s eyebrows furl and she says, “That’s the only thing you’re interested in? How I look?” In a split second, a boring conversation became contentious, with Brandon trying to dig himself out of the hole he’d just dug.

That’s what you’re trying to do with dialogue. You’re trying to find those lines and those moments that bring an energy to the conversation. You can’t do that if you already have pre-established conversations in your head or your characters are always responding to each other with expected responses. Dialogue will always be difficult. But it becomes less so when you stop trying to control it. Try these suggestions out and watch your dialogue come alive!

Carson does feature screenplay consultations, TV Pilot Consultations, and logline consultations. Logline consultations go for $25 a piece or $40 for unlimited tweaking. You get a 1-10 rating, a 200-word evaluation, and a rewrite of the logline. They’re extremely popular so if you haven’t tried one out yet, I encourage you to give it a shot. If you’re interested in any consultation package, e-mail Carsonreeves1@gmail.com with the subject line: CONSULTATION. Don’t start writing a script or sending a script out blind. Let Scriptshadow help you get it in shape first!

Genre: Horror

Premise: (from Black List) A woman with a troubled past invites her teen niece to live with her in the family’s farm house, but the two become tormented by a creature that can take away their pain for a price.

About: This script found some traction last year, allowing it to sneak onto the Black List. It hasn’t sold but it did get the writer, Christina Pamies, an assignment writing Baghead, a popular short film that they’re turning into a feature.

Writer: Christina Pamies

Details: 86 pages

One thing to remember whenever you’re writing a spec script is that, if the spec gets noticed, or better, purchased, it’s probably not going to get made. I’m not trying to bum you out. I’m just going off the percentages here.

However, that’s okay, because there are a lot of movies that ARE being greenlit that need a writer and, if those movies are in the same genre as your spec, you have a shot at getting an assignment that will turn into a credit. And credit is everything in this business. It not only gives you legitimacy. It ups your quote. It makes you a bankable writer, since you’ve proven that stuff you write gets made. And let’s not forget those glorious residual checks that keep showing up in the mailbox years down the line. You’re going to need them to fend off the bills of your 15 different streaming services.

This is why I always remind writers to write in the genre you love. Because you’ll probably get pigeonholed into that genre, which is great if you love the genre. But a nightmare if you hate it. Not to mention, you’re going to write better scripts in the genres you’re passionate about anyway because you’re naturally going to go the extra mile for them.

I’m only bringing this up because I remember when I first started writing and I would write whatever cool concept I came up with. I’d write a comedy then a sci-fi script then a drama then a dramedy then a horror then a sports movie then an action script then a thriller. I was all over the place. And when you start out, you might be all over the place too. But while writing in a bunch of different genres can be educational, it’s better to focus on the genres you love.

Because each genre has its own challenges and you want to master the genres you love as soon as possible, which means writing them over and over again. That’s how you get good at a genre. Which increases the chances of you selling one. Which increases the chances that you’re known around town as a good writer in that genre. Which increases the chances you get called in for an assignment in that genre. Which increases the chances that you get the assignment. Which leads to a credit. Which leads to you being a legitimate paid writer. Which is exactly what today’s writer, Christina Pamies, pulled off, when No Good Deed got traction around town and she got the writing gig for Baghead. Okay, enough lecturing. Onto today’s script…

40 year old Amy Sutton is at the end of a long cancer battle. It’s gotten so bad that she and her husband send their 11 year old daughter, Zoey, off to live with Amy’s cousin, Julia. They don’t want Zoey to see how bad things are going to get with Amy.

Zoey moans and complains from the start and lets Julia know that they’re anything but friends. The two head off to Julia’s farm house, which happens to have been in the family for 150 years. Julia has just recently moved into it, and is excited to show Zoey the place where she and her mom spent so many fun summers.

But weird things start happening. The house seems to be a favored spot for injured animals. Zoey immediately starts caring for an injured opossum (which leads to her getting bitten). Then, there’s weird plant problems that are growing out of control underneath the house, to the point where stubby plants are piercing the kitchen floor.

Later, Zoey spots an old timey family of 3 inside the bathroom. But that’s nothing compared to what Julia spots at the edge of the woods – a ten foot tall pale man-demon who spits out a bunch of bones.

You would think that these two would hightail it out of here. But they decide to stay and look into the home’s history. It has two major family slaughters that have happened in the house which include a seven-body scenario of pure human annihilation. A mystery that was never solved.

But when Zoey’s opossum bite starts unnaturally spreading and the local plant life does a full-on assault of Julia, it looks like these two are doomed. (spoilers) What we eventually learn is that the boneeater guy has promised certain people who live here safety if they feed him. Which means you have to feed him other members of the family. That’s what Amy – I think – did. She fed him for a while. But then she stopped. And that’s why she has cancer. So the question is, who made a deal with the boneeater this time? Who’s about to be turned into a lunchables snack?

After reading the very strong horror story that was My Wife And I Bought a Ranch last week, No Good Deed had a tough act to follow.

You really can spot the difference between the better horror entries in how much detail has been recruited into the story. The less detail and the shakier the mythology, the more horror falls apart at the seams. I mean here we’ve got killer plants, 10 foot tall boneeaters, old-timey ghosts, an animal connection, a teaser opener where a family gets slaughtered. It’s a lot of stuff that doesn’t feel organically connected.

Pamies does explain it all in the end in a way that somewhat makes sense. But that’s not the problem. The problem is the 80 pages where everything seems so disconnected that we’re less intrigued by the mystery than we are frustrated. I actually think the boneeater was a good monster. Why not just stick with him? We don’t need killer plants and sinister possums. That guy was scary enough on his own. And the “deal” stuff it makes with family members opened up some really interesting character avenues. You’ve been shown your death. But this guy gives you a way to survive. Unfortunately, you have to sacrifice a family member to do so.

The best part about this script is its almost brilliant ending. That being Zoe offering Julia to save her mom. The problem is, it’s unclear when they decided to do this. From what I understand, Zoey and her mom talk midway through the movie and hatch that plan. This would’ve been SO MUCH BETTER if that was the plan all along. That was the big twist. Her and her mom actually planned this to kill off her cousin so Amy could get better.

But this script has so many logic problems. The house is somehow both the most evil house in the world (so much so that everybody in the community is terrified of it) yet Julia spent her summers here and found it to be the greatest house ever. I struggled to buy into that. It felt like your classic ‘straddle the fence” screenwriter dilemma. You needed Julia to like this place so she’d believably take Zoey here. But you also needed to make it ‘Amityville times a million’ so we’d have a horror film.

I know these things are hard but you have to figure them out if you want the reader’s suspension of disbelief. Because the whole time I’m reading this, I’m thinking, “Wait, everyone else knows this house is hell except for this one woman who’s actually lived here before?” If I’m always thinking about that, I can’t focus on the story. Plugging up logic holes is the unheralded battle in screenwriting. You never get points for doing it even though it’s one of the most time-consuming things about the craft. But you have to.

Another problem that occurs when you have too much mythology to work into your horror script is that the scares start feeling random. Banging on walls. Scary furry animals. Old-timey ghosts. Killer plants. Boneeaters. You have to understand that, to a reader, randomness is only appealing up to a point. I liked, for example, that in The Ring, we had strange shit coming out of TVs and a weird video tape with a creepy short film on it. But if you start throwing too many different scares at us, it begins to feel like the story is desperate to scare us to the point where it’s willing to not make sense anymore – even if it makes sense eventually.

Like I always say, simplify things. Don’t over complicate it. Adding more complications hurts a story 98% of the time. All we needed here was the creepy boneeater and that shocking twist with Julia being killed (or almost killed but she somehow escapes) and we’re great. But in this current iteration, too much is going on.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Don’t bury your head in the sand on troublesome setup details. Cause I can guarantee you that readers will question them. And those questions will continue in the back of their mind, throughout the script, preventing them from being able to focus on the story in the moment. Another question that I couldn’t get out of my head was, why would a mom kick her daughter out of the house two weeks before she died? I couldn’t buy into that.

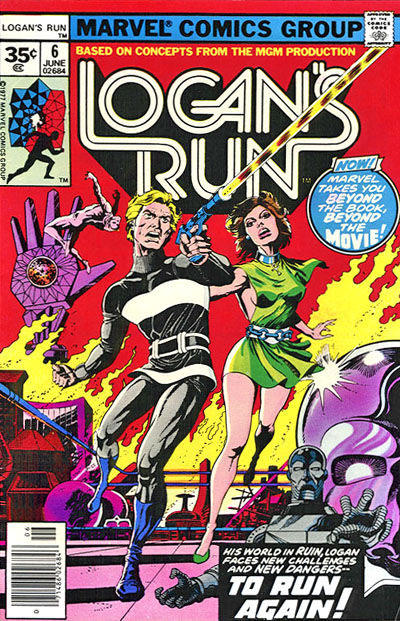

Genre: Sci-Fi

Premise: In the future, every man and woman must voluntarily die the day they turn 30. But there are a few who refuse to do so. Instead, they run.

About: There may not be a project in Hollywood that’s been more developed than Logan’s Run. An untold number of drafts have been written over the years and many directors have attached themselves to the project only to eventually move on. The draft I’m reviewing today is special as it was co-written by my writing crush, Alex Garland. One day Logan’s Run will be made. The premise is tailor-designed for a 2 hour feature film. But which combination of creatives will finally get it across the finish line remains unknown. For the ones that do, they might want to use this version of the script as a guide.

Writers: Alex Garland and Michael Dougherty (based on the novel by William F. Nolan and George Clayton Johnson)

Details: 2010 draft

Yesterday’s post got me all nostalgic for long-running projects in development hell and one of the most famous of those unmade movies is Logan’s Run. The project seems to have been greenlit a dozen times in the past two decades, yet it always seems to fall apart.

However, I know it will get made eventually. How do I know that? Cause it’s got the ultimate GSU factor working for it, baby! Goal, get out of the city. Urgency, everyone’s trying to get you. Stakes, you fail you die.

The briefly conveyed backstory of Logan’s Run (by the way, if you’re writing a big sci-fi script, the more briefly you can convey your backstory, the better) is that there was a giant war, so an AI dude named Thinker was created to come up with the best way to keep mankind alive. He constructed a city called Eden where the only rule you had to follow was, when you turn 30, you have to die.

Our hero, Logan, is 29. Or somewhere around 29. Nobody quite knows what their age is. That information is given to them via a color-coded leaf tattoo on the inside of your hand. Your leaf starts at green and by the time it becomes all black, you have to go to the “Sleep Shop” where they terminate your too-old ass.

Logan is a sandman. That means he’s the police for people who try to run after their 30th birthday. He will hunt you down and kill you on sight. You don’t even get the dignity of going to Sleep Shop. Logan isn’t just good at his job. He’s the best, with more kills than any sandman in history.

But things become a little extra real for Logan when his good friend and fellow sandman, Cassie, gets her Sleep Shop marching orders. Logan accompanies her to her death, where he’s allowed to watch as she’s taken into a white room and put to sleep. The event has a heavy effect on Logan. He’s always been told how honorable and amazing volunteering for sleep is. But this felt anything but honorable.

Logan is then called to see Thinker, the “doesn’t even try to hide how evil he is” A.I. dictator of Eden. Thinker says he’s heard of this thing called Sanctuary that some runners escape to. He wants to find out where this place is so he can stop it. Therefore, he artificially speeds up Logan’s hand leaf so his death day is…. TODAY. Uh, say what?? says Logan. You see, Thinker says, the best way to find Sanctuary is to become a runner. So Logan’s all of a sudden running for his life.

He eventually meets up with this chick named Penelope, who explains that she gives every runner a chance, even evil sandmen like himself. “Everyone deserves a shot at Sanctuary” is the underground rule. After lots of evading, Penelope leads them back to Sleep Shop, where you must sneak out of the city with all the dead bodies. Out past the mountains of dead people is where they will find Sanctuary. Or will they?

Last week I highlighted an early scene in Street Rat Allie Punches Her Ticket that leaned into the emotional connection of the characters. The reason I did that is to remind you that even when you’re writing a script that might seem like it’s surface-level summer fare, you still need to write scenes – especially early on – that emotionally connect us to the characters and the situation.

Here we get that scene when Logan accompanies Cassie to Sleep Shop. These two have been told their whole lives what an honor this moment is for the human experience. And yet, when they go through it, it’s anything but. It’s cold. It’s cruel. It’s empty. It’s terrifying. I loved how Garland and Dougherty chronicled every second of it.

Weak action writers shy away from moments like this. They want to get them over with as soon as possible because they feel like they’re betraying what the audience came for. “If the audience comes for a big fun action movie, we can’t give them a sad death scene,” is their fear. “They’ll be pissed off.” But these are the scenes that do the best job of connecting us with the characters early on so that we’re emotionally connected with them throughout the rest of the story.

Another thing I want to bring up is irony.

If there’s one thing where you can clearly recognize, as a reader, that the writer is NOT beginner level, it’s when they incorporate irony in a major way. Let’s say you’re writing Logan’s Run. Everything about your script is the same as it is here. The only difference is you haven’t decided who your main character is yet. They’re a blank slate.

You could’ve easily made Logan a street vendor. You could’ve made him a doctor. You could’ve made him a prominent businessman. And most writers in this situation would pick one of those jobs. I know that because I read all those scripts where they did pick those jobs.

That’s not to say these are bad choices.

But, by making Logan a policeman who specifically chases runners, it means that basing the movie around him becoming a runner himself is ironic. It adds more pop to the story. And where it really helps you is in the logline. Everybody loves a well-crafted ironic concept. A man with a major speech impediment must give the most important speech in history (The King’s Speech). So whenever I see that, it’s a good sign that I’m going to read a solid script.

Here’s the thing with these movies, though. You can’t have 90 minutes of running around. I mean, you could. But you’d be shocked at how quickly action becomes boring when you give us one action scene after another after another after another. So when you’re writing this kind of script (a ‘running away from the bad guys’ script) you want to structure the second act so that the ‘running’ set pieces are spread out. Between those running set pieces, you need planning and execution scenes. Those will actually take up the majority of your screen time.

A great movie where you can study this is The Fugitive. But Garland and Dougherty do a good job also. You’ve got Logan and Penelope, and they have to plan some objective (they need to find a guy who can help them, for example). The planning phase is figuring out where he might be and how they’re going to get in contact with them. Then they have to go try and do it. This is the execution part. And, of course, when they do it, something will go wrong, and they’ll be chased. But it’s really the planning and the execution that take up most of the screen time.

Some writers might be scared of that. I NEED TO GIVE THEM ACTION, CARSON! THIS IS AN ACTION MOVIE. Let me ask you this. What’s more enjoyable? The lead up to the roller coaster ride or the roller coaster ride itself? I’d say the anticipation of getting on the roller coaster is pretty darn exciting. That’s what you’re doing with your plan and execution scenes. You’re making the reader wait in line for the ride. They’re not going to be bored if they know there’s a ride at the end.

I didn’t have many issues with this script. The biggest mark against it is that it feels familiar. We’ve seen this format before. Oblivion did it. And I’m sure you guys can think of a dozen other movies with similar plots in the comments. So while the execution was good, it was working within a trope-heavy format that limited just how fresh and cool it could be. I mean, let’s be honest. This is a 50-year-old story.

Despite that, I found it to be really fun. And Alex Garland continues to be one of the most impressive writers around. This was such an easy read. 125 pages read like 95. His writing is so clear and unobtrusive. It’s designed to never have you stop and read a line twice. I love it. The crush remains.

Check this one out. Good stuff!

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[xx] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Two things you can play with that create really solid movie ideas are TIME and SPACE. When you limit those two things, it organically sets up a scenario that is easy for the audience to understand. Time here = 30 years. You have to run before you hit 30. SPACE is this contained city. It’s got walls. It’s got barriers. So it’s very easy for us to understand what the objective is. Logan needs to get out of the city. If your concept feels murky or unclear, use time and space to make it clearer.