Search Results for: the wall

Genre: Slasher/Dark Comedy

Premise: (from Black List) Swept up in the excitement of her wedding day, Dr. Julie Wheeler is oblivious to the killer on her guest list, who is methodically stalking her nearest and dearest, until its too late.

About: This is going to be a little weird because I’m writing this “About” section AFTER I’ve written the review. I do this occasionally because when I look somebody up ahead of a review, I find that their success (or lack of) influences what I write. It’s better when I read the script knowing nothing. That’s when I’m the most honest. So count me both surprised and not surprised when I found out that Jessica Knoll was a successful novelist (her novel, “Luckiest Girl Alive” has almost 4000 ratings on Amazon, which is super hard to achieve). You’ll notice in the things I talk about in the review why her being a novelist makes sense. Anyway, this looks to be Knoll’s first screenplay. Or, at least, the first one she’s sent out to people.

Writer: Jessica Knoll

Details: 108 pages

It’s really hard to find fun premises like today’s on the 2019 Black List. Check out a couple of the loglines I had to wade through to get to this one… “An absent mother attempts to reconnect with her daughter by relaying to her how she helped her own parent through battles with cancer and addiction.” Sounds like a page-turner. “A brother and sister navigate the perils of both man and nature through Central America in their quest to find safety in the United States.” Sometimes I think these loglines are used as cheap alternatives to euthanizing people.

But just like Hamilton, I’m not giving up! I’m not going to miss my shot (to read a great script). And today’s concept sounds fun. So hold my hand (in an appropriate socially-distanced way) and let’s check it out together as script friends…

SCRIPT FRIENDS UNITE!

An upper-class New York wedding is going on for 34-year-old biotech doctor Julie Wheeler and 37-year-old Tom Cunningham. They’ve brought everyone up to the Cunningham Ranch, which, in addition to being Instagram friendly, has been in the Cunningham family for generations.

But we got problems from the start. Such as bridesmaid Becca, who just slept with Tom’s twin brother, womanizer Dylan, is killed by a mysterious axe-murderer in the wine room!

Later, Jason (Becca’s husband), heads out into the woods looking for Becca, since nobody else seems to care that she’s missing. He’s met by the caretaker, Edith. Edith has been on these grounds since the beginning and has known Tom and Dylan since they were kids. Could she be the killer? We’re not sure. But she does warn Jason that Tom and Dylan are known to pull “switcheroos.”

Meanwhile, Julie and Tom get married. Everything seems great, although they find it strange that Jason, a groomsman, decided not to show up. Every couple of scenes, we’re reminded that there’s a dispute at the heart of the Cunningham Ranch deed. It’s supposed to be split between Tom and Dylan. But their mother, who divorced their father, is also getting half of the property.

Amongst all this, Julie is having to deal with her impossible-to-please mother, who thinks Tom isn’t anywhere close to the status of man she deserves. All this leads to the obvious question: Can Julie get out of this weekend alive? As in, literally?

Here’s something I always forget then I see it in a script and I’m reminded of it again. One of the Ten Commandments of screenwriting is don’t have your characters babble on in a scene. Make sure the scene is focused. Establish the point of the scene (what each character wants) then come into the scene as late as possible and get out as soon as possible. This is proper screenwriting etiquette so that your characters don’t talk forever and bore us to death.

However, if you’re good with dialogue, this rule doesn’t apply to you. You want to keep it in the back of your mind, of course. But if you can write lively, clever, fun, NATURAL interactions between characters, the reader doesn’t notice that the scene is long. We don’t care about that rule because we’re wrapped up in the interaction.

You can see this on page 6 in a scene where Julie is getting ready for the wedding. There’s a lot of chit-chat, backstory mentioning, even significant exposition – things that typically kill dialogue. But Knoll writes dialogue so effortlessly, we’re too busy enjoying ourselves to notice it.

So how do you know if you write good dialogue and can ignore this rule? You have to be told by at least three people who have read your work, unprompted, that your dialogue is really good. If no one brings that up on their own, stick to the basics. Clear scene goal. Get in late. Leave early. And yes, you’re cheating if you corner them with a, “So did you like my dialogue?? It was good, right!?”

If Til Death only had a bunch of these dialogue scenes, it would be in good shape. But after that scene, the plotting takes center stage. It’s all about herding characters to certain areas (it’s time for pictures!), getting a character alone so he’s exposed the potential killer. And lots of setup about the twins, the ranch deed, and complicated high society money problems.

Once the script got bogged down in that, it wasn’t nearly as entertaining. I liked it better when it was funny. The opening was funny. Julie talking to her friends in that scene was funny. But most of that goes out the window when it’s time to set plot points up.

And this is something a lot of new writers struggle to figure out. If you have a plot-heavy story, you don’t want to let the plot become a burden on the script. It can’t be this never-ending wall of information because then you lose the fun. And, literally, that’s what we get here. We get walls of text everywhere. 14-line paragraphs aren’t uncommon. This in a medium where you should be nervous writing a 4-line paragraph.

It seems to me like Knoll is a talented writer who’s new to screenwriting. Some of these mistakes are Screenwriting 101 stuff. And now that I’m thinking about it, that 10-page dialogue scene I praised may not have been a deliberate choice, but rather the writer not knowing that 10-page dialogue scenes aren’t common in screenwriting.

I’m going to talk about another ‘what I learned’ in a second but my preemptive ‘what I learned’ is to not overburden your script with direction. If there’s a lot of describing what’s going on and where we are and you’re mixing that in with lots of exposition-focused dialogue, that’s like forcing a soccer player to go out on the field holding a 30-pound dumbbell. It’s slowing everything down to a crawl and it’s hard to make a story work under those circumstances.

This got close to a ‘worth the read’ because I liked the premise and I liked the way the script started. But it lost its way under a heavy dose of too much plotting.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: A lot of good jokes come from establishing a sad or intense situation, the kind of situation that could only warrant serious reactions, and then you throw in a line that’s the opposite of serious. Early in the script, there’s a murder next to a wine rack and a couple of wine bottles fall and break, causing the wine to mix with the blood of the murdered body. It’s a gruesome scene. The caterer and his assistant are horrified by the victim’s death and worried about how to replace the wine (a couple of bottles of ’97 Piedmont) since the wedding is today. He decides on a cheap red wine replacement then says to the assistant, “And find a mop for this. (sniffs the air) And Febreeze or something. (sniffs again) Maybe we dodged a bullet. Smells like the ’97 turned.” You can use this type of humor successfully in any comedy. The more serious the situation, the better the surprise joke will play.

This is the second in a series of articles leading up to The Last Great Screenplay Contest deadline, which is July 4th. Today we’re going to talk about a common screenplay topic that remains one of the hardest to get right. And that’s character. Or, more specifically, how to set up your characters to give you the best chance of writing a great screenplay. Because if you can write great characters, everything else tends to fall in place.

I’ve been in innumerable conversations with writers where I’ve read their script, I didn’t like their characters, and afterwards they told me, “This is what I was trying to do with the character,” and what they tell me is in no way what I read. It’s a little bit like how we see ourselves versus how the world sees us. Those two streets don’t always line up. So I want to discuss some major things you can key in on that will help you execute the character in a way where the audience sees them like you do.

Picking a character audiences will respond well to

The first thing you have to do when you create a character is to pick a character who you think AUDIENCES will find interesting. This may seem obvious but what often happens is the writer prioritizes creating characters that THEY find interesting. And they never consider that that type of character won’t play well to others. The number 1 all-time example of this is the main character in a Duncan Jones movie called “Mute.” I read that script ten years before it was made and I could tell right then that the movie wasn’t going to work. The main character was mute and inactive. So there was no way for us to connect with him. I’m sure, Duncan believed, that by giving the character this impairment and throwing him into some rough futuristic exterior, it would make him appealing to people. But the truth is, it was boring. Cause the character was boring. Cause the character couldn’t talk. And the character was passive. So always consider how others will perceive your character and not just how you see them.

Character introduction

A strong character introduction is one of the most important things you will be tasked with. Audiences form the majority of their opinion on characters right away. Which means you need to get two things right. One, give us a character description that stands out and that conveys as much about that character as possible. A lot of good writers use “essence” character descriptions, which are descriptions that are less about the external and more about the internal. “His saggy posture and unkempt look denote a broken man,” is better, for example, than, “He has dark hair and brown eyes.” Once you’ve done that, you must give the character an action that is memorable and that tells us who they are. If your character is a jerk, intro her being a jerk to her co-workers. The combination of these two things – great description and strong action – will literally solve half your character problems. If you want to see a good character intro scene, go check out Ozark (Netflix), Season 3, Episode 1 for Ben Davis’s introduction (it’s in a classroom). Is it any wonder this previously no-name actor is now the hottest name in Hollywood? That’s what a powerful introduction can do.

The Flaw

The reason to give your character a flaw is because a) it instantly provides them with an additional layer, and b) it gives the audience a reason to keep watching them. Because if we care about a character’s flaw, we will care about them overcoming the flaw. The best ways to come up with a flaw are to put yourself in the character’s shoes and ask, “What’s holding me back in life?” Or to identify a flaw in your own character (as in you, the person reading this) and inject that into your fictional character. If neither of those work, look to your character’s situation and occupation. For example, if your character is a money manager, you probably want to give him the flaw of greed (The Wolf of Wall Street). If your character is a kid in a Youth Hitler Camp, you probably want to give him the flaw of close-mindedness (JoJo Rabbit).

Vices

The reason why the execution of vices varies so wildly (in one script, a drug addict is the most cliche character ever, in another, it leads to an Academy Award), is due to how the vice is implemented. A vice is something you should only add if it’s a) being used to forget something, or b) being used to escape something. If your character was sexually assaulted when they were a child, it stands to reason that they may turn to drugs to forget about it. If your character is in a loveless marriage, it stands to reason that they might turn to food (or smoking, or gambling) to avoid the pain of dealing with that. As long as the vice is being motivated by something, it works. But if you’re just making someone a drug addict cause you want a bunch of scenes of them shooting heroin? Be prepared to be hit with the cliche label.

The Compelling Character Dilemma

One of the most common questions I get asked from intermediate screenwriters is, “How do I give a character a flaw without making him unlikable?” Indeed, this is one of the trickier tightropes you must walk in screenwriting. You have to make your character flawed if they’re going to have any depth. But if they’re too flawed, we dislike them. Conversely, if they’re too perfect, we’re annoyed by them. The trick is finding balance. My solution is to use the Formula of Offsetting. Make sure there’s at least one more good or sympathetic trait than there is bad. What do I mean by “sympathetic?” Sympathy doesn’t have to be created within. It can be something pushed upon your character by the outside world. For example, if your character has a blatantly unloving father, we will feel sympathy for them. This is essentially why we’re okay with everyone being an asshole in Succession. Their father doesn’t show any love towards them. To use a movie example, “Joker” is about a creepy guy (1 bad trait) who cares for his ailing mother (1 good trait) and is picked on by everyone (1 sympathetic trait). The good trait and sympathetic trait outnumber the bad trait, so you’re good.

A couple extra points to make about this. The more mature the genre, the more you can lean into a character’s negative traits. Uncut Gems does not have the most likable hero. But it’s a dark indie thriller, a genre where the audience expects the character to be darker. So it’s okay. Likewise, if you’re going into a lighter genre, like a PG-13 comedy, you’ll want to lean a little more into the positive traits of the character. Also relevant to this discussion, the further away you go from the main character, the more negative traits you can get away with. Luke Skywalker wouldn’t work as a badass. But Han Solo, a secondary character, does.

I’m going to finish this up by sharing with you the single biggest character mistake I’ve ever seen in a mainstream film. And I would argue that this mistake didn’t just kill this movie. It killed this director’s career. Look at his movies before this moment and look at his movies after. It’s like night and day. And I genuinely think it’s because he lost sight of how to properly write a character audiences root for.

The movie in question is Vanilla Sky. It’s a Cameron Crowe movie starring Tom Cruise. The movie starts off giving its hero, David Aames, a clear flaw. He’s vain. That flaw is fine, I guess. I don’t think it’s as interesting as a lot of other flaws, but it’s something you can work with. And through the first fifteen minutes, the movie is interesting. A trust fund baby lives the upscale New York City party life us mortals could only dream of. There is an opportunity here to show how a flawed individual overcomes his infatuation with the material world.

And then came the scene.

The scene occurs at David Aames’ house party and David’s best friend, Brian, comes with a girl. David then proceeds, right in front of his best friend, to steal the girl from Brian. Your main character just stole the girl his best friend brought to his party. GAME. OVER. Audience gone. Viewers done. The movie died in that moment. We hated the main character SO MUCH that nothing afterwards mattered. You could’ve written freaking Citizen Kane 2 and nobody would’ve cared. I still can’t believe that Cameron Crowe actually wrote this scene and thought it was going to work. I bring this up to remind you just how critical it is to consider how your character is going to be perceived. If you don’t understand how your character comes across to others, screenwriting becomes very hard. Cause you can do a lot of other things brilliantly and still people will say they don’t like your script. Look at Cameron Crowe. At the time, he was considered one of the top 3 dialogue writers in the world. It didn’t matter, however, when he got the character wrong. NEVER FORGET THAT!

Hope the writing is going well! Share your character tips in the comments!

Genre: Sci-Fi

Premise: A billionaire gives up all his money before joining 200 passengers on a ship that will fly to a new planet.

About: Today’s short story was bought up out of the The New Yorker by Simon Kinberg’s production company. As you may remember, this is the second high-profile short story Kinberg has purchased in the past year. The first was Pyros, which I liked a lot. The writer, Thomas Pierce, will be adapting the story himself, and John Carter of Mars director Andrew Stanton, who has been steadily making up for that film with lots of TV directing gigs, will likely direct.

Writer: Thomas Pierce

Details: About a 15 minute read.

As I’ve said before, when you’re looking at short stories to turn into movies, you shouldn’t be looking for direct translations. You’re looking more at the potential of the story and where it can go.

Nowhere is this more true than with today’s New Yorker entry. Chairman Spaceman is an offbeat science-fiction story with little science fiction on display. One might even call it science-fiction adjacent.

It follows a guy named Dom Whipple, a 45 year old former billionaire, who has given up all his money and possessions to a church that is funding a trip to a distant planet. The church hopes to start a new society on this planet, and because Dom was so generous with all his money, he’ll be one of the 200 passengers.

We meet Dom 24 hours before the ship leaves. He’s having one last goodbye party with all his friends and ex-wife. The church assigns every passenger a sponsor. Dom’s sponsor is Jerome, who comes from the opposite end of the financial spectrum. He and his wife aren’t even able to make rent this month.

Dom, in a moment of weakness, has sex with his ex-wife and is convinced, for a couple of hours, that he doesn’t want to do this. He starts plotting a plan to get some money back and start over on earth. But a couple of hours later, he wants to go on the ship again.

That’s the thing with this story. It just sort of wanders aimlessly. It doesn’t seem to have a purpose. Dom wants this one minute. Dom wants that the next minute. At the very least, we know it’s going to end with him on that ship, so there’s reason enough to keep reading.

We learn a little more about the church and its plan. Apparently a first ship was sent two years ago with 10 pre-settlers (The Intrepid 10). It takes 16 years to get to the planet and if the first ship gets there and doesn’t like what it sees, it will alert the second ship, which will then turn around and fly back to earth.

The night before Dom is to leave, Jerome’s wife asks him for money. She’s convinced he’s got some squirreled away in the Cayman Islands or he can call one of his rich buddies and they can wire him a few hundred grand within minutes. Sorry, he says, he really has nothing left. Pissed off, she takes the last remaining money in his wallet and storms out of the room.

The next morning, Dom is shuttled to the ship. An attendant lies him down in his cryo-chamber and says that when he wakes up, he’ll be on the new planet. It’ll all happen instantaneously. He then closes the chamber and Dom begins freaking out. He changes his mind. He doesn’t want to go on the trip.

But the chemicals overpower him, he falls asleep, but a second later he wakes up and he sees all this activity outside. There are lots of people around, including a military officer and an old woman. That old woman turns out to be his ex-wife.

It’s been 30 years, they explain to him. When that other ship got to the planet, they found another intelligent species living there that attacked them, so Plan B was triggered in the second ship, which then turned around and went back to earth.

The final image is his ex-wife telling him that the world has changed a lot since he left it. The church that funded the trip isn’t even around anymore. So it’s going to be a rough transition. The End.

The only way I can categorize this short story is “frustrating.”

It’s impossible to figure out what it’s actually about. It doesn’t help that it tries to weave this religious thread into the story. In my experience, religion and science-fiction don’t mix. We just saw this a couple of weeks ago with the similarly constructed “Raised by Wolves,” which, coincidentally, has this same two-ship storyline, but focuses on the first ship arriving on the planet.

Chairman Spaceman bounced around from idea to idea so recklessly that it could never settle in to what it was trying to say. There’s this theme about rich people giving all of their money and possessions away that holds some potential. But here it’s treated as backstory. It’s so detached from the plot line that it only barely informs Dom’s character.

There’s the weird decision to give him a sponsor. Why does he need a sponsor? Usually a sponsor has a purpose. Like, if you’re a drug addict, you can call your sponsor to help talk you down from shooting up heroin. But this guy is a sponsor in name only. He’s there to follow Dom around and talk to him once in a while.

The moment where Jerome’s wife asks Dom for money is the only true “scene” in the story, something you could imagine being in the screenplay. And yet it’s so random. We barely know Jerome. We know his wife even less. Why is she getting one of the only memorable scenes in the story? And what does this moment have to do with anything else?

There could’ve been a cool thread about how this religion exploited super-rich people to fund this mission. But Dom is the only rich person on the trip. It’s one of many outlier variables in this story that contribute to its pointless feel.

There are only two interesting things in the story. The first is that Dom seems to have a sketchy past. He did some horrible things to become as rich as he did, including possibly killing a man. I wanted to learn more about this but, as was the modus operandi of the author, anything interesting was barely given focus.

The other thing – and this is where I think the movie is – is when Dom gets back from the trip. This is where I would start the movie if I were the producer. This is a man who had it all. But then he gives it away to go on this trip. The trip fails. He comes back 30 years later. He has no money. He has no business. All his contacts are dead or no longer in the game. I want to see how that man reintegrates into a future society.

Or, another way you could do it is you make the short story the first act. You set the movie up as if it’s going to be about going to this planet. You would NOT tip the audience off (like they do in the story) that the mission has a failsafe to send them back if something goes wrong. You want that twist to be a surprise. So you set the movie up to be about them arriving on the planet at the beginning of act 2 and then – BAM – the mission was a failure, 30 years has passed, and he has to reintegrate into a society that he doesn’t understand.

The only other way I could see this narrative working is if they do a 25th Hour sort of deal where the movie focuses on the 24 hours leading up to him leaving. How you say bye to everyone. You start to have second thoughts. Inject some uncertainty as to whether he’s going to go through with it. But I find the 30 Years Later idea to be way more compelling.

What do you guys think?

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Start your screenplay as late into the story as possible. If you’re writing a short story, like this one, and especially if you’re writing for The New Yorker, you can experiment. Short fiction is one of the more experimental writing mediums. But when you’re writing a movie, it’s a different ballgame. You’re writing something that will hopefully make millions of dollars. So experimentation is mostly off the table. For that reason, you want to start your story as late as possible. The most friendly scenario for a movie would be starting with Dom waking up after the mission failure. That way, you’re jumping in right at the beginning of when things get interesting. That doesn’t mean you can’t do what I said above – have the first act be him prepping to leave and then leaving. But the further back you go from the moment your story gets interesting, the harder it is to hook the audience. They’re going to get bored and they might not even make it to the good part. So keep that in mind when you’re adapting something AND when you’re trying to figure out where to start your own movie idea.

If you asked 100 of Hollywood’s top producers, directors, actors, and writers, who the hottest screenwriter in the world was at the moment, the majority of them would say Phoebe Waller Bridge.

Bridge is killing it all areas of screenwriting but the thing she’s best known for is her dialogue. It’s been a long time since we’ve had a screenwriter whose dialogue was this celebrated, so I thought, why don’t we break some of her dialogue down?

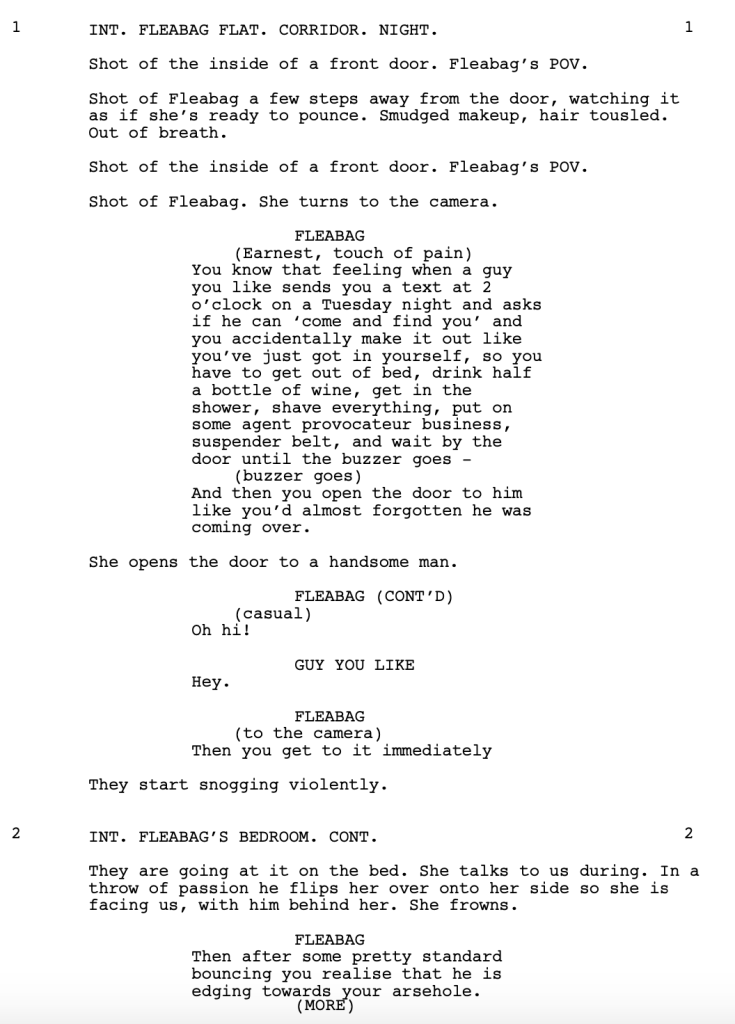

And what better scene to dissect than the opening scene of the Fleabag pilot. Do not worry if you’ve never seen the show. I’m going to include the pages here for you to read.

The first lesson for why this dialogue is so great is our most important one. Fleabag is a talker. She’s the definition of a dialogue-friendly character. One of the biggest mistakes writers make is they try and inject punchy dialogue onto characters who wouldn’t say those things. Imagine putting John Wick in this scene. He’s not going to give you anything close to what Fleabag is saying because John Wick operates with his gun, not his tongue.

So if you’re ever anxious about writing good dialogue in your script, the job starts long before you’ve written a word. You want to conceive of a primary character – it doesn’t have to be your hero but it does have to be a key charcter – who likes to talk or who says interesting things or who says controversial things or who’s clever or who’s funny or who’s weird or who talks first and thinks later. This decision will dictate 90% of the quality of your dialogue.

The next thing we’ve got going here is that Fleabag talks directly to the viewer. Now some people hate characters who do this. I get it. My feeling has always been, if you’re going to do something that ballsy, you better have the skills to back it up. There’s nothing worse than a “clever” character talking to the camera who’s a big fat ball of lame.

But assuming you’re good at breaking the 4th wall, doing so achieves a unique effect. It both breaks the monotony and it breaks up the predictability of the conversational flow. You’re no longer dependent on His Turn to Talk, Her Turn to Talk, His Turn to Talk, Her Turn to Talk.

This is why I’ll tell writers that just because Character A asks a question, that doesn’t mean Character B has to answer. They can say nothing and Character A can move on to the next line. At least that way, you’re breaking up SOME of the monotony of the conversation. But outside of a few other tricks, you’re relegated to His Turn, Her Turn, His Turn, Her Turn.

Once you throw this new option into the mix of your protagonist talking to a third person that the second character can’t see, that gives you a rare opportunity to do all sorts of creative things with the dialogue, which is exactly what Bridge does here. I mean you have two characters exchanging dialogue who aren’t even talking to each other. He’s talking to her. She’s talking to us. It’s creativity like this that opens the door for a slew of new options.

The next thing Fleabag does is she talks about things you’re not supposed talk about. Again, this doesn’t come out of nowhere. It’s baked into the character so you have to make that choice early on. But once it’s there, it’s powerful because there are very few things left that are taboo. And the fact that Fleabag consistently finds the taboo subject and talks about it so openly provides something very rare in movie and TV dialogue, which is that you don’t know what the character is going to say next.

You know how in 90% of movie conversations, you can approximately predict what the next line is going to be? Those moments never happen on Fleabag. You’re always unsure of what she’s going to say next and that’s a major key to keeping people watching. As soon as audiences figure out what’s coming next, what’s their incentive to continue?

I don’t want to overlook the technical side of dialogue here so I want you to go back to the first page and reread Fleabag’s opening monologue. Notice that IT’S ONLY ONE SENTENCE. It’s not grammatically correct. It’s not aesthetically perfect. It’s a big messy run-on sentence. However, it fits the character and it fits the situation. She’s someone who rambles on, especially when she’s drunk and horny. If this monologue had been broken into four proper sentences, it wouldn’t have felt right.

Finally, the dialogue is honest and authentic to the character who’s speaking. It isn’t movie-logic dialogue where the writer is attempting to imprint their cool lines or relevant thoughts onto the character. “But you’re drunk, and he made the effort to come all the way here so, you let him.” I don’t know a lot of writers who would be willing to go to this place. It’s borderline uncomfortable to hear. But that rawness, that realness, is what makes it authentic.

One of the best ways to study dialogue is to find a scene that has good dialogue then imagine what the scene would’ve been if written by an average writer. Because those are the scenes I read thousands of times over and have become bored by.

I mean think about how many scenes have been written where a guy or girl comes over for a booty call. Now try and think of any that are as good as this scene. Go ahead. I’ll wait. It doesn’t matter. You won’t find one.

I bet you the scenes you tried to find have the obvious funny initial text exchange. Maybe some clever quip about boning. Cut to the guy showing up. There’s some drunk dialogue. Then they smash. It’s just so… predictable.

When you can take that common of a scenario and twist it into something we’ve never seen before, that’s what’s going to set the stage for a good dialogue exchange. Because you can only do so much with the standard setup.

To summarize everything: First we have a dialogue-friendly character. Fleabag says whatever she’s thinking. She has zero tact. Next, the fourth wall option provides an opportunity for dialogue creativity. This makes the scene read different from what we’re used to. The dialogue is risky in places. It’s authentic to the main character. And, overall, there’s a desire to explore and be playful. You’re not going to find good dialogue the way you find a good plot. You have to be more open and relaxed and allow the words to flow through you. If you try to control them or you try and logically build a great dialogue exchange, it’s not going to work. Conversation is often illogical.

It’s funny. Despite Hollywood universally agreeing that Bridge is an amazing dialogue writer, whenever I post one of these breakdowns, there are always commenters who scream out, ‘THIS IS THE WORST DIALOGUE EVER, CARSON! YOU’RE WRONG.’ I welcome these comments. I only ask that you back up your claim. Give us some analysis on why the dialogue is bad. Dialogue is always one of the more polarizing screenwriting topics so I expect some fiery debates.

What’s that old saying?

Turn lemons into lemonade?

Well by gosh, that’s what we’re going to do here at Scriptshadow.

We’re indoors for the next few weeks. Let’s make the best of it.

I know a lot of you are hard at work on your Last Great Screenplay Contest entries. So feel free to follow this journey for fun. But for the rest of you, we’re going to write a screenplay…

IN TWO WEEKS!

I know, I know. Sounds impossible, right?

Don’t worry. I’m going to guide you through every step. I’ll be here for the good and the bad, the highs and the lows. Trust me, it won’t be as hard as you think.

And just to be clear – I know that nobody’s going to write the next Citizen Kane in two weeks. But what you can do is write a first draft that contains the bones for a great screenplay. We’ve heard tons of successful writers tell this exact story. Jon Favreau wrote the first draft of Swingers in a few days. Sylvester Stallone wrote the first draft of Rocky in what? A week?

And with me by your side, I’m going to make sure you don’t make any of the classic mistakes writers make when writing quickly.

Now the actual writing doesn’t start until Monday. But we’re going to get started right now.

“Whoa, Carson. Give me time to… like… breathe. You’re throwing a lot at me here.”

Good. This process is going to feel a little uncomfortable and that’s a good thing. The only way this is going to work is if you push yourself outside of your comfort zone.

We need to come up with a concept.

Maybe you already have an idea you’ve been sitting on for a while, itching to write. Maybe it’s an offbeat concept that’s always scared you a little bit. This is the perfect opportunity to bust that idea out and write it because what’s the downside if it’s bad? You lost two weeks. No biggie.

But for those of you hoping to write something specifically marketable, you’re going to come up with five loglines for potential screenplays… BY TOMORROW.

“But… but Carson… writing… takes… time. Come up with five ideas in one day?? That’s impossible!!!”

Stop.

Just stop.

One of the primary directives of this experiment is to eliminate negative thinking. Eliminate doubt. Doubt slows you down. We don’t have time for it. We have to write a script in two weeks.

You’re going to come up with five loglines and then, tomorrow, you’re going to e-mail five of your friends OR five people on Scriptshadow OR post your loglines in the comments section and you’re going to get a consensus on which is the best idea. That’s the idea you’re going to write.

One of the BIGGEST mistakes screenwriters make is starting with a weak idea. It’s hard for even the best screenwriters to make a weak concept work. You want to give yourself the best chance to succeed. This, more than any other decision you make, is going to have the biggest impact on whether your script is good or not.

A word of advice. Don’t pick ideas that have too much mythology, require too much research, or have too many characters or storylines. While it’s possible to write one of those scripts in two weeks, they tend to take longer than that.

So any fantasy concepts like Lord of The Rings – throw them out. The Big Short, a script that would require extensive research about the 90s stock market – throw it out. The Godfather, Gladiator, World War Z, Avengers. These will be tough scripts to write in two weeks.

Simple concepts with low character counts will be the easiest to write. Rocky. Get Out. A Quiet Place. Ladybird. Parasite. Marriage Story. Joker. Swingers.

I don’t want to stifle creativity so if you have an idea that doesn’t fit this mould and it still appeals to you, by all means, write it. Just be aware that the more characters there are to track, the more time it will take to work out the plotting. And the more complex your plot, the more likely it is you’re going to run into walls. Walls are where screenplays become tough. You hit a thick one you don’t have answers for and that can keep you away from the computer for days. We’re only going to finish a script in two weeks if we’re writing EVERY SINGLE DAY so keep that in mind.

One of the themes you’re going to hear me hit again and again these two weeks is LACK OF JUDGEMENT. Judgement is the main reason for writer’s block. For those of you who struggle with that, these two weeks are going to be a revelation. Because it’s not about writing something great. It’s about writing something period. And then, when it’s over, we can look back at what we’ve written and decide if it has potential to keep working on. If it doesn’t, that’s okay. We only lost two weeks. And we didn’t even lose much because we were going to be home with nothing to do anyway.

So that’s all you have to worry about today. Either pick some idea you’ve been sitting on for a while or come up with five loglines. Tomorrow’s comment section will be dedicated to sharing your loglines so that fellow writers can give you feedback on which one is best. However, if you want to get a head start, feel free to post your loglines in this comment section. I only ask that you post all five of your loglines in a single comment. Don’t keep gumming up the comments section every time you come up with a new idea. “Is this good?” 30 minutes later. “What about this one??” Let’s avoid that.

Another theme you’re going to hear me hitting over and over again is: Let’s have fun. A lot of times we get bogged down in the frustrations that come with writing. We’re throwing that to the wayside here. We originally got into writing because we enjoyed it. And these next two weeks, we’re going to get back to that mindset. Let’s have some fun and write a script! It’s not going to be any more complicated than that.

I already know some of you are itching to leave a comment about how this is bad for screenwriting. Nothing good is ever written in two weeks. You’re going to come up with reasons why you’re different and why you can’t do this. That’s fine. I will give you one day, here in this comment section, to get those thoughts out. Cause I get it. Writers are often pessimistic creatures. But after today, those comments won’t be allowed. I will delete them.

Moving forward, it’s going to be about staying positive so that we can get a screenplay written. It’s going to be a blast. I can’t wait to see what you come up with. :)