In today’s post I reveal something that very few screenwriters know – which is the number one thing that leads to a boring script. And it’s going to shock you.

This weekend’s weak box office is relevant to today’s conversation – specifically the box office failure that was I.S.S. – because I’m going to talk about how to avoid writing a boring script. The 2024 Two-Script Challenge is upon us. We’re starting Screenplay Number 1 next week. So I want to show you guys how to avoid boredom and even achieve the opposite – the big thing that makes a screenplay exciting.

I.S.S. came out this weekend and barely made 3 million dollars. I reviewed the script a few years ago and identified the main problem all the way back then for why it wouldn’t do well.

It was boring.

I’m not roasting the film’s box office because it didn’t have much of a marketing push. First weekends are almost always about how big the marketing push is. This film got very little of that. I’m more focused on the audience score, a C-. C- in audience score parlance is the equivalent of an F- -. It means the audience really disliked the film. And I know why. Because the script was boring. Check out my old script review to get some more context as to why the film was doomed.

But we’re talking about a different movie today: the big-budget Netflix movie, “Lift.” “Lift” is an exceptionally fun idea, one of the better concepts I’ve come across in a while. A team of bad guys are going to pull off a heist on an airborne airplane. That’s a “licking your writing chops” type of screenplay. The possibilities are endless.

And yet, the final script is so devoid of entertainment, we’re left to wonder, what happened??

For those who haven’t seen the movie – and that appears to be most of America – it follows a mastermind named Cyrus who steals a lot of high-value things. He works with a team of heisters, the most memorable of which is a guy named Denton, who’s weird and a master of disguise.

When Interpol agent Abby learns that an international terrorist is transferring half a billion dollars worth of gold on a plane, she realizes that if she can steal his gold, she can prevent him from funding any more of his terrorism. So she (at her boss’s urging) gets Cyrus (who she once had a fling with) to come up with a plan to steal the gold in-flight. Cyrus recruits his team and they prepare for the most impossible heist in history.

Sounds fun, right?

Yet, by every metric, the movie doesn’t work. It’s got a 5.5 on IMDB, a 30% RT score, and the most damning metric: a 31% audience score. This is a movie made for the audience, not the critics. That score hurts badly.

But here’s the thing. The movie isn’t bad. Bad is what happens when you take a big swing and whiff. It’s Battlefield Earth. It’s Southland Tales. It’s Howard the Duck. Lift suffers a much worse fate: It’s boring. And today I’m going to teach you about the number one thing that makes a script boring. Because you’re about to write your first script of 2024 and I want to make sure it doesn’t suffer the same fate as Lift.

Who here thinks they know what makes a script boring? The number one thing. Everyone stop reading and go make a guess in the comments. You’re not allowed to re-edit it. When you’re finished, come back up here so I can tell you what it is. Cause I know. I’ve read enough boring scripts to be able to tell you the exact reason. And that reason is going to surprise you. Cause it surprised me when I first figured it out.

Are you ready for it?

Are you sure?

I don’t think you’re ready. But I’m going to tell you.

The number one thing that makes a script boring… IS WHEN IT’S WRITTEN WELL.

Wait, what??

That can’t be right. If you’ve written a script well, you’ve done a good job.

No, actually, you haven’t. All you’ve done is give the reader the exact experience they were expecting. And that’s what makes a script boring. Cause readers don’t want to get what they expect. They want to get what they couldn’t have come up with themselves. They want to be surprised.

And if all you’re doing is checking screenwriting boxes to get your script written, what you will have is a technically proficient script without any soul. It will get the job done but it will feel empty.

As I watched Lift, I noticed that the writer was doing the technically correct thing every step of the way.

We get the big flashy opening set piece to pull us in – a heist of an NFT. We introduce our mastermind and our Interpol agent, who once had a relationship together, and now must team up for this heist.

The heist itself is impossible. Getting onto a plane mid-flight to steal 150 tons of gold is as hard as it gets.

We then introduce all these little smaller problems that the heist team has to solve in order to achieve the ultimate goal. All that is exactly what you want to do in a heist film. It’s about the team trouble-shooting to pull off the heist.

Those are just the basics. There are tons of other character-related things (bringing in a “wild card” character in Denton) that are technically correct as well.

That’s what’s so frustrating about screenwriting. Is that you can do everything right yet still write a weak script.

But how can that be true?

Well, one of the things I’ve said before but I probably need to say more often is that a script’s strength is not in the things that the writer does right. It’s in the risks that the writer takes that have the potential to be “wrong.” You see, it’s the blemishes that make a movie stand out. A perfectly smooth face is boring to look at.

Look at Joker. That entire movie is built around something you’re not supposed to do in screenwriting – which is to make your hero an unstable psychotic murderous person who isn’t easy to like. That was a HUGE RISK. Which is exactly why, when it worked, it worked exceptionally, making over a billion dollars.

Promising Young Woman came out during a time when it wasn’t considered okay to make female characters “crazy” or possibly be in the wrong. That was a huge risk. Yet that’s exactly what made the character so interesting. If they would’ve made her yet another Mary Sue who could do no wrong, which was considered the “right” thing to do in screenwriting at the time, the script would’ve been boring.

Now, I know what a lot of you are thinking. Those are artsy movies where it’s easier to take risks. That’s true. In fact, concepts like Lift are the ones MOST SUSCEPTIBLE to being boring because they’re mainstream and, therefore, don’t allow for a lot of flexibility in the creative part of the execution.

But I promise you this. If you don’t take SOME RISKS in whatever script you’re writing, your ceiling is a boring script. I say “ceiling” because you might not even get the script to the point where it makes sense, which happens a lot with newbie writers. But even if you execute it perfectly, without risks, it’s going to be boring. Cause a million movies have come out just like it, and by following their formula, you haven’t given us anything new to celebrate.

So you have to take risks. You have to try some things. One of the best recent examples of a mainstream script taking a big risk was Spider-Man: Homecoming. That whole thing where Mary Jane was the Vulture’s daughter – that could’ve gone horribly wrong if the audience didn’t buy it. I’ve seen versions of that choice in other movies where the audience violently rolled their eyes while mumbling “Give me a break.” It was a big creative risk. And, as a result, it’s the thing everyone remembers about that movie.

So you have the ability to be risky in these scripts. It’s just harder. Just don’t let that deter you. A boring script is the worst version of a script you can write. Not just because no one will remember it. But because it actually takes a lot of effort to write a perfectly proficient script. And then you get no reward for it. You might as well take some risks along the way so that the script has a shot at being memorable.

Feel free to share some notable creative risks you’ve seen in big films in the comments section. Cause I know most of you are writing marketable Hollywood movies for the 2024 Challenge. So I want you to see how other writers of these films have taken risks that have paid off.

One of my favorite characters from 2023 (Duncan Wedderburn in Poor Things)

One of my favorite characters from 2023 (Duncan Wedderburn in Poor Things)

Okay, it is WEEK 3 in our WRITE TWO SCRIPTS IN 2024 Screenwriting Challenge. Week One was playing with possible concepts. Week Two was solidifying a concept. And now we’re on to Week Three – FIGURING OUT YOUR CHARACTERS.

Usually, when writers write scripts, they start writing IMMEDIATELY after they’ve come up with their idea. This is almost always a mistake. When you jump into a script too quickly, you burn out fast. You’ve got a runway of about 20-40 pages but you never build up enough speed to take off.

You erroneously figure your premise is too weak and you abandon your script like an alcoholic abandons their family. Whoa, that just got dark. Disregard that. Actually: REGARD IT. This post is about character. And character flaws are crucial to understanding your next steps.

This is the part of script-writing NO ONE WANTS TO DO – the character work. It’s boring. It’s hard. It doesn’t allow you to have any fun, since it’s all backstory and, therefore, doesn’t fill up any pages. Yet, it’s probably the most important work you can do for your script.

In my experience, getting the characters right is the single most important aspect of a screenplay. You can have a bad plot, but if you have great characters, you can write a good screenplay. Meanwhile, if you have bad characters, even if you have a great plot, the screenplay will suck. The reader will not care what happens unless they care about the people taking us there.

If you create a character who we like, give them some kind of resistance within them that they’re battling, and show them succeed – if you get that right, NOTHING ELSE MATTERS.

However, we need to do a deep dive to get there. I don’t need to know when your character had their first kiss (unless it’s relevant to the story) or what their favorite food is. That stuff does help. And if you want to do that work, I’m all for it. But I’m looking for something more important.

Here’s what I want you to do this week. You’re going to make a list of your 4-5 major characters – the ones who have the most screen time. You’re then going to figure out the five major character pillars of each. These five pillars are…

Likability

Personality

Flaw

Arc

Central Relationship

Let’s go through these one at a time.

LIKABILITY

I got news for you. If we don’t like your main character, there’s a very good chance we won’t care about ANYTHING they do. Which means you can write the greatest story ever and we’ll still hate it because we don’t like the person. Go back through all your least favorite movies and I can pretty much guarantee you didn’t like the hero. So you have to figure out why your character would be liked by others. And no, you don’t get to ignore this one if you’re writing a dark comedy and your hero is a tough pill to swallow. You then have to figure out how to make your hero sympathetic. If they can do it for Joker, you can do it for your script. You want to have such a solid reason for why your hero is likable or sympathetic that, if you were taken to court on the matter, you would win the case hands down. That’s how persuasive your argument should be.

Here are a few recent movies and why their characters were likable or sympathetic. Willy Wonka – The nicest kindest person you’ve ever met. Ken in Barbie – All he cares about in life is getting this one person to notice him but she won’t. We can all sympathize with that since we’ve all had that person (people) in our own lives. John Wick – He’s sympathetic cause his wife died and they took his dog. He’s also likable because he’s a nice guy with good morals. Robert McCall (The Equalizer) – One of the most likable characters in movies because all he cares about is helping people who can’t help themselves, to the point where he’s willing to risk his secret identity to do so. Louis Bloom (Nightcrawler) – He’s the ultimate underdog in this night-crawling business (audiences love underdogs) and he’s obscenely driven (audiences love characters who are driven, cause driven people are active, and audiences love activity).

PERSONALITY

This is one of the most overlooked aspects of character creation in screenwriting and if you don’t pay attention to it, you are likely to have a boring main character. This happens ALL THE TIME in the amateur scripts I read. The writer makes all the surrounding characters fun and interesting but they assume that their main character needs to be so grounded that they don’t have any defining traits whatsoever. Which is a huge mistake. You have to give your character some personality.

The best way I know how to do this is to figure out your character’s sense of humor. Your sense of humor dictates the majority of your personality. Are they sarcastic? Do they like gallows humor? Are they goofy? Are they the “dad joke” type? Are they deadpan? Are they quick-witted?

Going beyond the humor, what other aspects do they bring to the table that help them stand out in a conversation? Are they sexy, like James Bond, who has that twinkle in his eye whenever he speaks to a woman? Are they intimidatingly smart, like Robert Downey Jr’s Sherlock Holmes? Are they cocky? Are they charismatic, like Ferris Bueller? Are they quirky, like Bella Baxter (Poor Things)? These are just some ways to identify your character’s personality. Define it as tightly as you can because if you don’t, your character is going to sound untethered. We’re never going to have a good feel for them.

FLAW

This is obviously a big one because it’s the thing that most defines your character within the context of your movie. Writers can get tripped up by flaws. But they’re easier to figure out than you think. The character’s journey in the movie will determine how you identify their flaw. For example, if the movie is about a banker trying to get rich, the flaw will probably be greed. If the movie is about being the best at something (Nightcrawler), the flaw will revolve around recklessness or perfectionism. If someone wants to be the best at all costs, that’s their flaw – they don’t know when to stop. If the movie is about a “my way or the highway” coach who’s trying to take a basketball team to the championship, the flaw would be stubbornness. He’s not able to listen to anyone else but himself.

Think of the flaw as the NEGATIVE part of your character’s personality. They have good things. But this is their one bad thing. And it’s usually the most dominant part of their personality. Some writers have asked me if addiction is a flaw. It can be. But it’s usually what leads to the addiction that’s the flaw. So if someone struggles to connect with others but can connect with them when they’re drunk, then they might develop an alcohol addiction. But it’s not the alcohol that’s the flaw. It’s their fear of connection. That’s what they need to overcome. Not the alcoholism.

ARC

Now that you know the flaw, you have to figure out how you’re going to arc your character over the course of the story. A well-constructed character arc is one of the most satisfying storytelling experiences an audience can have. We audiences love to see that broken character overcome that flaw that’s been holding them back the whole movie (which we extrapolate to mean ‘their whole life’) and finally change. It’s not the good guy beating up the bully at the end that gets us. It’s that our good guy’s flaw was that he was a coward and he’s finally overcome that cowardice to become brave, which gave him the strength to stand up to bully at the end. THAT’S WHAT GETS US. When George McFly punches Biff after being Biff’s punching bag the whole movie, we cheer because George has finally overcome his flaw, his cowardice.

Unfortunately, an arc isn’t just about establishing a flaw at the beginning and having them overcome it at the end. There’s all that in-between time as well. This is your second act and you want to set up three to four big scenes where your hero is faced with the opportunity to overcome their flaw but they fail. We need to see these little failures along the way for the big final change to feel genuine. So, as you’re constructing the arc, I want you to think about these 3 or 4 scenes in your script where you’re going to challenge your character’s flaw. And then, also, figure out what that final climactic scene is going to look like where your hero is faced with that opportunity to change once more and he finally does.

CENTRAL RELATIONSHIP

There are no characters in a vacuum. You can’t express a character unless they’re bouncing off other characters. So you want to figure out what the central relationship in your movie is, then strategize how to get the most out of it. For example, in Titanic, the obvious central relationship is Jack and Rose. You don’t want to wait until you start writing to figure out how that relationship is going to work. You want to identify what the major source of conflict is in that relationship so that whenever the characters are together, they’re dealing with that conflict.

In that movie, Jack’s the kind of guy who lives by the seat of his pants. He does what he wants to do whenever he wants to do it. Rose is the kind of person who plans 8 moves because she has to. She’s in a prison – a bunch of rich people who live a highly structured life. And that’s what makes their relationship interesting. Their worldviews are opposite. If James Cameron had envisioned Rose as this cool chick who is more of a rebel, then Rose and Jack are too similar and you don’t get as much conflict. More recently, you can look at Tony Stark and Steve Rogers. Stark is willing to get dirty to get the job done. Rogers plays by the rule book. Those worldviews are what creates the conflict that drives that relationship.

Figure out these five pillars for, at the very least, your hero and your biggest secondary character. If you can extend it out to more characters, even better. I promise you that the more you know these five pillars, the more confident you’ll be going into your script. What you have to remember is that there’s the story being told by your plot (Save Barbie Land) and the stories being told within your characters themselves (Ken – must overcome his feelings of worthlessness and find purpose if Barbie doesn’t want him). If you can create a great character story, your script will be impervious to plot issues. I know that sounds crazy but it’s true. To this day, Swingers is one of my favorite movies. It also has one of the worst plots I’ve ever seen in a script. But it works because the characters all have their clear through-lines.

Okay, get to it! Next Thursday, we’re outlining our plot. Which means that, yes, you finally get to start writing your script in Week 5. Can’t wait!

Genre: Sci-Fi

Premise: Told in real-time, a man who recently broke into Area 51 stops at a motel and begins to execute his plan to send the incredible footage he took to the five biggest news sources in the country.

About: This script finished Top 15 on the newest iteration of the Black List, a list of the best scripts in Hollywood. Screenwriter Connor McKnight does not yet have any professional credits.

Writer: Connor McKnight

Details: 108 pages

“Jellyfish” UFO (I’ll explain later in the review)

“Jellyfish” UFO (I’ll explain later in the review)

First of all.

Aliens are coming.

Whether you want to accept it or not, they’re here on this earth and this is probably going to be the year that it’s officially exposed. Social media is preventing the powers that be from controlling that story. What the government is realizing is that if they let this come out randomly (someone posts a UFO video that they can’t debunk), they’ll have no control over the fallout. So it’s in their best interest to officially announce it themselves because at least that way they can spin the situation the way they want to.

All of this is why 10/24/02 was one of the first scripts on my radar when the 2023 Black List came out. Area 51? Aliens? Count me in.

The ONLY thing I’m worried about is if this is gonna be Gooftown 3000. We’ve evolved past the silly treatment of this subject matter that we saw in movies like Independence Day (“Welcome to earth!”). It’s a little more real now. I’m hoping this script reflects that.

We’re somewhere in New Mexico in 2002. A man named John – actually he has a lot of names but he’s John for most of the movie – races into a ratty old motel on Route 66 for the night.

John checks into Room 7 with a mysterious duffle bag and suitcase. He then heads outside and unscrews his Nevada license plate and replaces it with a Florida plate from another car in the lot.

Back inside, he opens up the duffle and we see glimpses of high-tech gadgetry. John then calls a frantic man named “Doc.” Their conversation keys us in on the fact that John just went somewhere he wasn’t supposed to be and took something he wasn’t supposed to take. He’s been driving ever since.

John shares with Doc that he has the computer movie files from inside that area, an area we now know to be Area 51. John plays the audio of one of these files to an orgasmic Doc, who hears what both of them have suspected for so long – that we are indeed in contact with aliens.

John has five copies for five different jump drives, which he has pre-prepped manilla envelopes for, being sent to the Chicago Tribune, New York Times, Washington Post, CNN, and the Los Angeles Times. A mailbox across the street picks up mail at 6 a.m. He’s going to place the envelopes in there at 5:55. All he has to do is wait.

Except that 30 minutes later, Doc calls back and tells him to check the news. The news shows that there is a national manhunt for John. That he “killed two men.” John and Doc know that this is serious and they both start freaking out. Especially after a new unmarked car pulls up into the motel parking lot.

Not long after, John’s ex calls and starts screaming at him about the news. We realize that John has been insisting on an alien presence forever and that his wife got sick of it and left him. But this is too far, she says. Even with John pleading his innocence, it doesn’t matter.

And that’s when things get really bad. Two mysterious men all of a sudden move into the rooms surrounding him and a frantic Doc calls back to say that he’s in his car and unmarked cars are chasing him. John hears gunshots. At this point, John realizes this is no longer about getting the truth out there. This is about one thing: SURVIVAL.

I’m going to provide you with a trick. A screenwriting trick, as it were.

If you’re writing a cheap movie that isn’t going to have much going for it – bare-bones production design, minimal locations, barely any actors – SET IT IN REAL TIME. “Real Time” is an automatic movie turbo-booster that costs NOTHING. It nearly makes any idea high concept.

We see that here with 10-24-02. It takes place entirely in and around a motel, and it’s riveting specifically because it’s real time. I don’t see this working if it’s not real-time. Case in point, that movie Bad Times at the El Royale. Abysmal movie. One of the worst of the decade. Just like this movie, it took place at a motel. It had much higher production value, big actors playing lots of parts. But it just SAT THERE. Nothing happened.

Whereas here, even though we only have one character, it feels like a million things are happening at once because of the real-time setup.

In many ways, this is one of those dream ideas. Not because it’s the best idea in the world. But because it’s a high concept idea that can be shot for a thousand bucks in one boring room. That’s what every young producer wants – an exciting idea that can be shot in a room for nothing. I would’ve loved to have snatched this up as a producer.

There’s another thing going on here that’s important to note for anyone writing a single location low-character-count screenplay. It has to feel like you don’t have enough time to tell your story. It can’t feel like you’re trying to fill time up.

There’s a distinct difference and 99% of the time, I see writers doing the latter. They’re searching for anything that will allow them to get up to those 90 pages. It’s a false victory though. You’re like, “Yeah, I did! I wrote a feature-length script!” Sure, but it doesn’t matter if those pages weren’t entertaining.

I genuinely felt like McKnight didn’t have enough space to put everything in here. He had to make choices on what to fit because there was too much story. That’s how you want to feel as a screenwriter. And not just for real-time scripts. For any script.

It’s fine to feel like you’re filling up space in your first draft cause you’re still discovering your story. But by the time you get to that 5th and 6th draft, you should feel like you’re having to take a lot out because you don’t have the space to keep it all in. What then happens is you’re forced to only keep the best stuff. Which is exactly how you want it. You only want your all-star scenes and plot points in the script.

All right, it’s time to leave the fictional world and hop into the real world of alien disclosure. The big video that’s being touted right now is the jellyfish UFO which was caught on video by a U.S. military drone. A lot of you are going to dismiss this just off the fact that it’s a “jellyfish” and that doesn’t sound like aliens, at least the ones we’ve heard about. But you have to understand that these “jellyfish” sightings go back years. A lot of people have seen them. You can google it. This is the first or second time we’ve gotten one on video. I don’t know what it is. I just know that it’s definitely alien. And it’s just the beginning of what’s going to be a crazy 2024 in the UFO space.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[xx] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: One of the most effective scenes you can write is a character HEARING but not SEEING someone else in danger – the reason being that the individual reader’s imagination does all the work. It’s thinking up what’s happening which is usually more exciting than being given a literal description of what’s happening. One of the most exciting moments in this script is when Doc calls John from his car as he’s being chased by the government. And all we hear is them shooting at Doc, getting closer, him running into a roadblock, and then just terrifying noises. I find that those scenes work really well on the page AND on screen.

What I learned 2: If you are ever at a loss as to what to title your sci-fi screenplay, use numbers. Numbers work extremely well with sci-fi.

The short story sale only took 45 years to happen

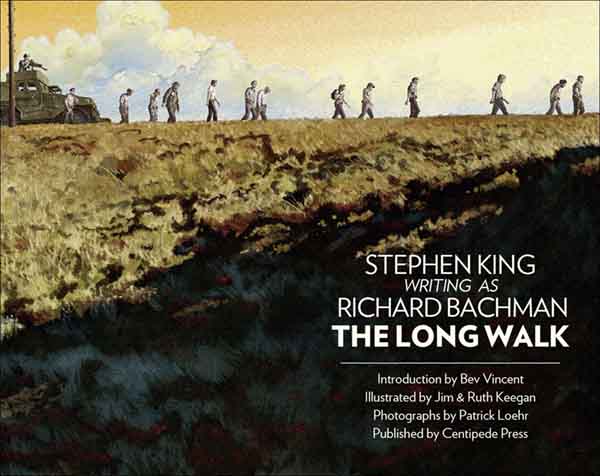

Genre: Dystopian/Sci-Fi Adjacent

Premise: 100 teen boys participate in an annual event that forces them to do a death walk until there is only one left.

About: Okay, I’m cheating a little. This isn’t technically a short story. But it’s a short story in Stephen King Language, as the man is known for writing 700 page novels. Technically, he would call this a novella. King also wrote this under his fake author doppelgänger, which King invented once he became too popular and figured everyone was buying his books regardless of whether they were good or not. He wanted to challenge himself and see if he still had it as an author, which is why he invented Bachman. The Long Walk, which is 45 years old at this point, was purchased by Lionsgate and will have Hunger Games director Francis Lawrence direct. The film was almost made twice before, once by George A. Romero and once by Frank Darabont.

Writer: Richard Bachman (Stephen King)

Details: (1979) A little under 250 pages, hardcover.

I’ve decided that I’m going to do a Short Story Showdown at some point this year. I’m not sure when but it will probably be June or July. So start coming up with that short story concept because we can’t deny what the current trend is, which is short stories, short stories, short stories.

If I could give you one piece of short story advice, come up with a big idea. Think “high concept” even more so than you would a script. Cause a lot of these short stories are a quarter the size of a screenplay. So you don’t really have time to put your characters through some complex arc. It’s more about a sexy idea that’s going to generate interest in potential moviegoers.

The Long Walk is a great example of this. It’s all about the idea. Let’s see if it offers us anything else.

16 year-old Ray Garraty was chosen to be one of the contestants for The Long Walk, a yearly competition where thousands of boys enter their names in a hat for a chance to compete for the grand prize – all the money you need for the rest of your life. Only 100 names are chosen and Ray is one.

No sooner do we meet Ray than the walk begins! The rules are simple. You have to keep up a pace of 4 miles per hour. If you don’t, you get a warning. You get three warnings total. The fourth time, they shoot you. As in, THEY KILL YOU. The last remaining person to be walking is the winner.

Ray immediately teams up with a guy named Peter McVries. Whereas Ray is more of a wholesome chap, Peter’s got an edge to him. It feels like he’s hiding a few secrets inside that noggin of his. But Peter seems to be as supportive of Ray as he is himself. The two lean on each other a lot as the first contestants “buy their ticket” (Long Walk code for “shot dead”).

The story doesn’t deviate much. It leans into the long grueling competition of trying to keep walking when you’re tired, when you get a Charlie horse, when you get a cramp, when you’re bored, when you get blisters on top of your blisters, when your shoes come apart, when your body wants to give in. Many a contestant tries to game the system – run into the crowd to escape, thinking the guards won’t possibly shoot at them. But it never works. The crowd wants to see them die so they push them back to allow the guards a clear shot.

15 miles turns into 20. 20 to 50. 50 to 100. Days go by. 5 of them in all. Somehow, some way, Ray keeps going. At a certain point, it’s just Peter and Ray. (Spoiler) But then Peter can’t go on. He’s too exhausted. Which means Ray is going to win. When Peter is shot, that’s exactly what we think. It’s over. But did Peter lose count? Is there another player he must outlast? Or is that player death himself? Is Peter even in the game anymore?

A few of you are probably asking, “Why’d you pick this to read, Carson?” Here’s why. The Hollywood system is so obsessed with the word “no,” due to the fact that it keeps them from having to make a decision, that when they finally say “Yes” to something, it’s a really big deal. It’s so hard for any executive to say yes because they know, once they do, that project could go horribly bad and, if it does, they’ll be fired. It’s probably the best view into an exec’s mind you’re going to get. Committing to anything is so daunting that there HAS TO BE SOMETHING SPECIAL about that project for them to say yes to it.

But if I’m being honest with you, the real reason I chose to read this as opposed to a script that sold or a script that made the Black List, is that I knew it was going to be entertaining. King has his storytelling faults. But his stories always place “entertaining the reader” first. So I know I’m going to enjoy the experience of reading The Long Walk.

I’ve read too many scripts to know that most writers don’t prioritize entertainment when writing a story. They’re writing for their own egotistical reasons. Or they’re trying to write something that’s taken seriously. Or they think that readers will stay with them for thirty pages of setup to get to the good stuff.

All King thinks about is the reader. That’s why he’s the most well-known living author. If every writer could take in just a quarter of that desire that King has to entertain people, their scripts and stories would be so much better.

And that’s exactly what happened. I was entertained from the jump.

I mean, do you know how quickly we get to the walk here? Within the first ONE PERCENT of the story! That’s how determined King is to entertain. He knows why you bought this book and he’s going to deliver on that promise. This is especially important with short stories. Not only do you need a high concept premise. But you need to get into that premise faster than when you’re writing a script.

What’s interesting here is that the entertainment comes at us in an unorthodox way. I’m not surprised at all that George Romero was once attached to this because the deaths here aren’t fast and furious. They work more like zombie deaths, where they come slowly. The people involved realize minutes, sometimes hours, ahead of time, that their death is coming. This makes the deaths more realistic, intense, and emotional.

When one kid tells Ray that he’s got a cramp and he’s looking to Ray for help, Ray looks back at him like, “I can’t do anything for you.” And the realization this kid has that nobody can help him is devastating.

That’s the majority of the book. King introduces us to kids along the way, tells us just enough about them to get us to care, then kills them off later on.

Another thing I liked about this story was the rules.

As with any sci-fi (or sci-fi adjacent) story, you have to have rules. Where so many writers screw up is they make their rules too complicated. Or they have too many of them. Or both. Note how simple the rules are here. You have to keep up a 4mph pace. You get three warnings. On the fourth, they shoot you. That’s it! For some reason, writers think that they’re not getting enough out of their story if the rules are simple. So they invent all these complicated rules. But the opposite is true. When the reader easily understands the rules, all they have to do is enjoy the story. They don’t have to constantly rack their brain to remember a + z = q.

Another great lesson you can take from this story is how impossible King makes it feel. With every script you write, you need to make the goal as impossible-feeling as you can AS EARLY as you can.

Ray is not dead tired on mile 97 when there are 3 kids left. He’s dead tired on mile 20 with 97 kids left. That’s how to make the reader wonder, “How in the world is he going to last?” And if the reader is asking that question, I guarantee they’ll keep turning the pages. It’s only when there are no questions left to answer, or the answers to the questions are obvious, that the reader stops reading.

The story does have narrative limitations. It starts to get monotonous since there’s only one thing to do. And I thought that King could’ve done more with the Ray and Peter friendship. If he could’ve made us love this friendship, like he did the kids in Stand By Me, their final walk together would’ve been a lot more emotional. And then, the ending needs work. You could tell King didn’t know how to end this. Luckily, there are options here, starting with strengthening that friendship.

Overall, a solid story that should be a good, but not great, movie.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[xx] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: A sound strategy for screenwriting is to see what the hot new trend is and go back through your finished scripts to see if you have anything similar. You can do this starting from scratch (writing a brand new script) as well. But trends are finicky. They can last a year. They can last five years. So any sort of head start is preferable. There’s no doubt in my mind that this story got purchased due to the success of Squid Game. And, to be fair, it’s been a while since that show came out. Regardless of that, the quicker you can move on a trend, the better. So if you have that old abandoned spec that is similar to the hot new thing, dust it off, give it a quick rewrite, and get it out there!

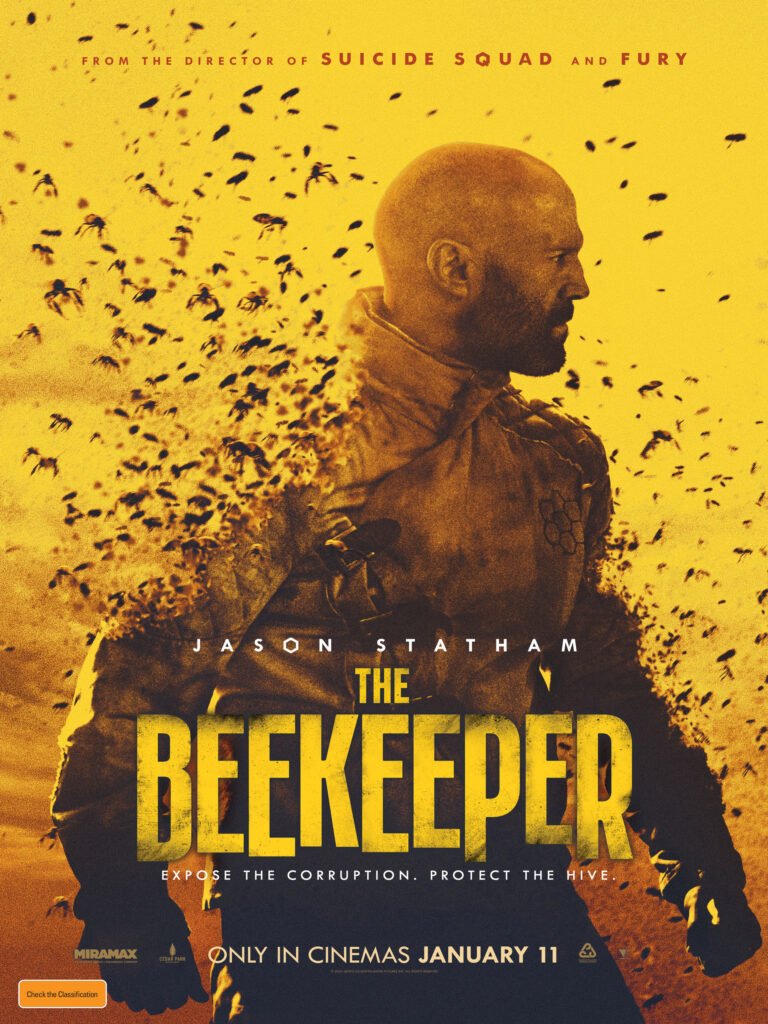

I tell you how The Beekeeper script sold for a million bucks and share with you some screenwriting lessons from Anatomy of a Fall and Self-Reliance

January is always a funky month in the box office schedule. It used to be a dumping ground for studio movies that tested terribly but, these days, if you have a marketable movie, fun things can happen. Which is why Mean Girls pulled in north of 30 million bucks this weekend.

A lot has been made of the fact that Mean Girls hid that it was a musical in order to get more people to show up. This strategy has always baffled me (they did it with Wonka as well). If you know people don’t want to show up to a musical, why did you make a musical?

Cause neither of these films needed to be musicals. They each would’ve worked as regular movies. I’m guessing in the case of Wonka, it was to get Timothee Chalamet on board. These vain actors are all about proving how versatile they are. So if Chalamet is offered ten common roles and one musical, he’s going to take the musical. Cause that’s the one where he gets to prove the most. So maybe they did it to get him and then began their crusade to convince the rest of the world that they weren’t actually making a musical.

Whatever decisions led to keeping Mean Girls’ dirty little secret, I’m not sure it mattered. Mean Girls is a classic film. It’s still referenced today. So it did well for the same reasons that most franchises do well these days – nostalgia.

The movie I was keeping closer tabs on was The Beekeeper. I reviewed the script last year and loved it. Kurt Wimmer is one of my favorite spec script writers. There are few screenwriters who know how to make readers turn the page better than him.

His process is a strange one, too. He writes 12 screenplays a year – a new one every month. And then he just keeps his ear to the ground on what people are looking for. If an opportunity comes up (his agent calls and says Gerard Butler really wants to make a helicopter film), he goes through his giant script database to see if he’s got a helicopter script.

The way this project came together – and I know this cause Kurt told me – is that Kurt had a previous relationship with Jason Statham and Statham had just gone through a major upheaval with his representation. He fired his agents and managers. He then called Kurt and said, “Do you got anything for me?” And Kurt had just finished The Beekeeper. Statham loved the sound of it and he was in.

I think the reason it’s doing solid business and that audiences are really liking it is that there’s nothing else out there like it. It’s kinda weird. It’s kinda silly. Yet it has this hardcore action component. It really is its own thing. Which is something I tell all writers – you have to give us a script that differentiates itself from all the other scripts out there. You can’t expect to write Type 1 concepts and get people excited.

Will Beekeeper become a franchise? If so, it has to pull off what John Wick did. Not a ton of people saw John Wick when it first hit theaters. It took off once it came to digital. That told Lionsgate that there was a big audience for the film, which is why they gambled on a bigger budget sequel. When that did well, each successive film budget got higher.

Cause, right now, The Beekeeper can’t compete on an action level with John Wick 4 or Fast and Furious. It doesn’t have the budget. To get that budget, it needs to perform like gangbusters on streaming. That’s probably the template for anyone wanting to build a franchise from scratch these days. It’s not like The Matrix anymore, where you become a franchise the first movie out. You have to build that audience.

I watched a couple of movies this past week, each of which provided screenplay lessons. The first was Anatomy of a Fall, which is a big awards contender. It’s a French movie that follows this married writer who lives with her husband and blind 12 year old son out in the middle of nowhere.

One day the husband’s dead body ends up in front of the house and it’s unclear whether he accidentally fell from the third floor, purposely jumped to commit suicide, or if his wife, our protagonist, attacked and pushed him off. The majority of the movie takes place in a courtroom where the prosecution tries to prove that she murdered her husband.

First of all, the movie’s fun to watch if only to see how the French court system works. It’s so bizarre and different from American court. It’s a lot more theatrical. You can’t believe that that’s how they really try people for murder.

But, beyond that, the movie is a failure (spoilers follow) due to the fact that they never tell you if she murdered him or not. If you’re going to build your entire premise around the question of did a woman kill or not kill her husband, then NOT GIVING US THAT ANSWER is cowardly.

You’re a coward because you were afraid to make a creative choice. I say this not just because of this movie. But because I see it all the time in screenwriting. A writer builds their entire story around a question, then doesn’t give the reader the answer. In their minds, they are being artistically courageous. Only hacky mainstream Hollywood movies answer questions, they reason. “Real” movies, movies with “artistic merit,” are vague and ambiguous. They allow the audience to come to their own conclusions.

Bulls#$%.

You can tell yourself that. But what you really are is spineless. You see, if you fashion yourself an “artist,” you can’t give your script a Hollywood ending. So you can’t give us the mainstream answer, which is that she didn’t murder her husband.

However, since there are only two options here – she did or didn’t do it – you know that the jaded readers will find the other avenue just as cliche. In other words, if you say that she did it, the “cool kids” in the audience will roll their eyes and say, “Of course she did. We saw that coming from a mile away.”

So your solution is to not give us any answer. “You figure it out,” you say.

Let me make something clear to you. If you are offloading the work that YOU SHOULD BE DOING and making the reader do it instead, you’re not being an artist. You’re just afraid to make a choice.

Is making a choice going to make some people unhappy? Of course. But it’s your job as a writer to write with conviction. Stand behind your choices. Write towards something you want to say. Don’t make the audience do the work for you. That’s lame. Because I know this writer knows if she killed her husband. They were just afraid to share that truth. That’s unacceptable.

Another movie I watched this weekend was a film on Hulu called Self-Reliance. Jake Johnson writes and stars in the movie. I’m a Johnson fan because he’s from Chicago (where I’m from) and there’s not one person I know who better looks and acts like a Chicagoan than Jake Johnson. Sometimes, when he speaks, I feel like I’m listening to myself.

The movie follows a guy with a boring job whose 15-year girlfriend broke up with him so he moves back in with his mother. Then, one day, he’s approached by some people who tell him he’s been chosen for a game. The game is a dark web game where he’ll be remotely recorded and people will try and kill him. If he can survive for 30 days without getting killed, he wins a million dollars.

He decides to join the game because of a small loophole in the rules which states that he can’t be killed as long as he’s with somebody. So he figures, I’ll just keep someone next to me the whole 30 days. As it turns out, being physically within someone’s presence 24 hours a day isn’t as easy as it seems.

A few people e-mailed me after my Concept Post on Thursday and asked, “Is it possible to write a low-budget Type 2 concept?” And the answer is, “Yes.” To quote the late great Montell Jordan: “This is how you do it.” This story is built around a game where you’re trying to avoid assassins for a dark web audience. It doesn’t get any more high concept than that.

Unfortunately, this script is an example of what happens when a newbie writer makes a movie. I know that Johnson has writing credits on a few other films but, from what I understand, those were improvised acting movies where the director gave him a writing credit cause he was making up his dialogue as he went along. Here, he’s actually writing a script.

Where newbies often go astray is that their tone bounces around too much. Here, we have this dark heavy game. But then later, when he teams up with another female player, it turns into a lighthearted romantic comedy. You can’t do that in screenwriting. You gotta pick a lane.

Actually, let me rephrase that. Anything’s possible. As I pointed out earlier, The Beekeeper is equal parts intense and silly. But The Beekeeper was written by a 30 year professional screenwriter who’s literally written 100+ screenplays. You have to go through the trenches to know how to balance tone. If you’re new to this, trying to fit wildly different tones into the same script is the equivalent of riding a roller coaster standing up. Loopdie-loop? More like loopdie-dead.

In this case, had Jake committed to that darker tone, it would’ve taken a 6 out of 10 movie, which is how IMDB currently rates it, to an 8 out of 10. Cause I was into the movie when it was dark and unpredictable. The second it became a rom-com, my interest nose-dived. So it’s not just about matching tone. It’s about sticking to the story you promised the reader you would tell.

Then again, this is that weird movie month where up is down and north is south. So it might be worth checking out if you liked the sound of the premise. I STILL haven’t watched Holdovers. That’s going to be my next one. Oh, and Sisu. A few people have told me that one was good.

Two quick reminders before I go.

CHOOSE THE CONCEPT FOR THE SCRIPT YOU’RE GOING TO WRITE BEFORE THURSDAY. We’re going to start the outlining process.

Also, this is another reminder that January Logline Showdown is January 25th. So get those loglines to me before then!