Search Results for: the wall

Genre: Dramedy

Logline: A blackballed entertainment lawyer puts her negotiation skills to the test when her beloved oldest daughter announces that she’s putting off college to become a feminist porn star.

Writer’s Pitch: This script examines just how messy and complicated modern feminism can be when ideals get translated to real life. The story is personal and timely and incredibly important to me. I think it will elicit strong reactions — both positive and negative — and it would be invaluable as I continue to develop this story to hear a variety of takes from readers male and female, young and old — not just Carson. (I’m saving my cash for a private consultation on my next script :) ) Bonus: At 89 pages with a lot of white space and humor, it’s a very fast read.

Writer: Angela Bourassa

Details: 89 pages

Last week’s Amateur Showdown comments section got a little messy, as it does whenever a writer attempts something different. Bourassa wrote her script in first-person, a huge no-no when it comes to screenwriting. Why is it a no-no? Because screenplays are supposed to act as instructional manuals for another group of people to go off and make the movie you’ve written. You’re writing to them. Under that logic, it doesn’t make sense to write in first person.

But as screenwriting has evolved into a more personal relationship between writer and reader, there’s been some flexibility in that rule. Screenplays have arguably become pseudo-noevellas, and, in the process, lost a lot of their strictness. While a first person screenplay is the most extreme version of this, it’s not the first time I’ve encountered it. However, if you’re going to use it, two things must be in order. One, you should have a good reason for doing it. And two, since the device will lead to more scrutinization, your script will have to be better than most.

Jenny, a proud 40-something black entertainment lawyer, is being handed a couple of pills in the doctor’s office when we meet her. We don’t know what those pills are for yet, only that Jenny looks stressed out about what the doctor’s just told her. From there, Jenny heads to middle school to pick up her 14 year old mixed-race daughter, Priya, who she spots making out with a 16 year old white boy.

Immediately, we sense that Jenny is fighting a daily battle – a battle to be progressive and supportive of her family, despite the permissive narrative in her head to be traditional and protective. So Jenny tries to smile about her daughter’s new boyfriend who, no doubt, will be pushing to have sex soon. Even if she’d do anything in this moment to make him disappear forever.

It turns out Priya is the least of her worries, though. When she gets home, her 19 year old super-cool beautiful perfect daughter, Indiga, informs her and Jenny’s husband, Amit, that she has something to tell them. She’s a) queer (they’re thrilled), b) wants to take a year off of college (sounds reasonable) and c) wants to make porn.

I’m sorry say what?

Indiga assures her mother that this isn’t “porn” porn, but rather porn for women. It will be feminine centric, body positive, instructional, and fill a market need. What Jenny isn’t yet aware of, is that she’s just been given the BAR exam for feminism. She should support her daughter if she wants to get into the sex industry. It’s what an empowering feminist would do. But she’s still this girl’s mother. And it’s porn!

Jenny huddles with Amit and the two discuss a plan to talk their daughter out of this. This problem is compounded by the fact that whatever Jenny was at the doctor for is eating at her, her professional career is floundering, her other daughter, Priya, wants to get an IUD, her husband’s artistic pursuits don’t bring in enough money, and her other child, Zack, is having trouble attracting girls. It will be up to Jenny to sort all this out in a way that makes both herself and Indiga happy, a task that will put her feminist ideals to the test.

Let’s begin with this first-person thing since I know it will be a hotly debated issue in the comments. While the first-person angle grabs our attention right away and makes the script different, I don’t see it as necessary for this story. Angela mentions the Pruss Passengers script, which also had a first-person perspective, but if I remember correctly, the first person there was relevant to the story. Aliens were “riding” human beings, and that allowed us, the first person narrator, to occasionally become an alien, which was crucial to the experience.

With The Dirty Work, I could see this being written in 3rd person and nothing changing. Maybe we don’t know Jenny as well, but there are tell-tale actions you can use to make up for us not being in her head. With that said, it does help the script stand out. So I’ll leave it up to Angela on whether she wants to keep it or not.

As for the script itself, it feels a bit thin to me. I liked the hook a lot. You set up the most progressive feminist mother ever and then give her the ultimate test – her daughter wants to become a porn actress – and see if she’ll stay true to her feminist ideals. But the script doesn’t really know where to go after the hook. There’s no narrative drive.

I know that yesterday’s film was as different from today’s as could be. But the narrative drive was always clear – climb the mountain. Here, the goal is to, I guess, stop her daughter from being in porn. But it’s dealt with in too casual a manner. One of the issues I had with the script was that I knew what the end result would be. I knew Jenny would support her daughter. So the goal is more symbolic than actual. She’s not REALLY trying to stop her. And we feel that in their scenes together. Jenny will make a point, but then immediately feel wrong about that point. This created an overall lack of suspense and the rest of the plot suffered as a result.

A good script problem has to have an uncertain answer in order to keep the reader engaged. Since this is Oscars weekend, we’ll use a famous Oscar winning script as an example. In Good Will Hunting, the question dictating the story is whether Will Hunting will remain a “nobody” working blue-collar jobs the rest of his life, or go off and use his talent to do something special with his life. The movie does an excellent job making you wonder which way he’ll go. The best stories ride that line the whole way through.

Part of the reason The Dirty Work is predictable is because of the type of porn Indiga is doing. She’s doing the nicest most pleasant most neutral form of porn possible. If your daughter did porn, this is literally the form of porn you’d choose for them. That was a major factor in me being able to predict what Jenny would do. This got me wondering, if you changed this to a more severe form of porn (regular male-female porn) would we be less certain what Jenny would do. I think we would. Then again, that alters the tone somewhat, so you’d have to weigh the advantages against the disadvantages.

As for the rest of the script, I felt the male characters were underwritten. Indiga and Priya have legitimate problems whereas Zack’s biggest issue is relegated to will he ask a girl out or not. And I definitely think we could do more with Amit. From my understanding, Indians have a very complex relationship with porn. The traditional culture out there looks down on it. That seems like the perfect opportunity to create more conflict between both Amit and Indiga and Amit and Jenny.

Finally, the script had a weak climax, no pun intended. The big final scene has Jenny negotiating Indiga’s porn contract. The idea behind this isn’t bad. Jenny’s entertainment law business has struggled. This is her “opportunity” to show that she’s still got it. But there are too many things hurting the scene, the biggest of which is that if she loses, she wins. If she loses this negotiation, it means her daughter doesn’t do porn. So why wouldn’t she lose on purpose? To be honest, it feels like this ending was rushed and that there’s a better ending out there.

Moving forward, I would dial everything up in this script. There’s not enough conflict. We never truly feel there are any problems between Jenny and Indiga. Even when they get mad at each other, it’s a polite mad. The more conflict you create in this relationship, the more doubt we’ll have that things are going to end well. And that’s what you want every story to feel like right up til the end – that things aren’t going to end well.

But I think this idea has potential. It has something to say in this day and age, and the hook is a strong one. A few more drafts and this feels like something that could make the Black List. It’s just not there yet.

Script link: The Dirty Work

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Scene Agitator Deluxe – A scene agitator is an outside force that repeatedly bumps against your characters while they’re trying to do something else in a scene. Say your characters are having a fight. Well what if, during the fight, the fire alarm keeps going off, forcing them to pause the fight while one of the characters deals with it. They fix it, go back to the fight, then a few moments later, it goes off again. That’s a scene agitator. Today taught me that there’s a deluxe version of this. This is when you add a scene agitator during a pivotal scene, allowing that scene to level up even higher. During the pivotal moment when Indiga tells her parents that she wants to do porn, Priya has just come home and the car pool parent who drove her is outside waiting for gas money he’s owed. So Priya keeps asking her mom for the money (the agitation) while Indiga is dropping this bomb on her. Clever move! You can read more about scene agitators in my book.

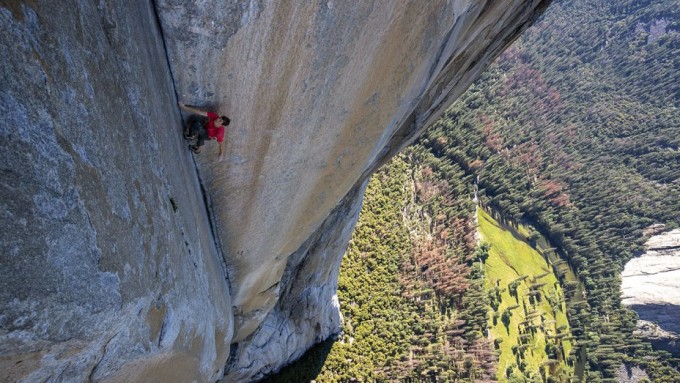

For those who haven’t seen it yet, Free Solo is a documentary about a climber, Alex Honnold, who engages in the most difficult and dangerous version of climbing that exists – free solo’ing. This is when you climb mountains without the help of ropes or partners. One mistake and it’s a 2000 foot drop to your death, where you’ll have about 30 seconds to wonder, “Why did I get into this sport again?”

Alex is considered the best free soloer in the world. But despite climbing hundreds of mountains, there’s one he can’t get out of his head – Yosemite’s El Capitan, a sheet of rock that goes straight up for 3000 feet. It is considered the most dangerous free solo ascent in the world. So much so that nobody’s even attempted to climb it. Alex has spent the last eight years gearing up for this climb. This movie documents him finally achieving the feat.

As soon as I finished the movie, I thought of screenwriting. This is one of the best templates for how to write a screenplay I’ve seen in years. That’s because climbing a mountain is the perfect metaphor for the hero’s journey. In the GSU (Goals, Stakes, Urgency) model, climbing the mountain is the story’s “G.”

But what Free Solo reminded me was that it can’t just be any mountain that the hero climbs. Is has to be the most impossible mountain. This film doesn’t work without the phrase, “the most dangerous free solo ascent ever attempted.” You sub in, “one of the harder free solo attempts in the world” and the movie loses its spine. Who cares about conquering a “sort of difficult” mountain?

Free Solo also reminded me just how big of a deal stakes are (the “S” in GSU). We’re always told that the stakes of our hero’s journey must be huge. Well what’s bigger than you slip and you die? I’d say the stakes of this movie are 75% of the reason it’s become a sensation. It just so happens there’s another climbing documentary out right now called The Dawn Wall that follows a climber climbing an impossible wall. The difference? He’s using ropes. He can slip 100 times and it doesn’t matter. Is it a coincidence that Free Solo is blowing that documentary out of the water?

But the great thing about Free Solo is that it doesn’t just explore the outer journey. Like any good screenplay, it focuses on the inner journey as well. Alex has a classic fatal flaw. He’s unable to connect with others. There’s an early scene where he’s dragged to a party and you can see how uncomfortable he is around others. Alex, it turns out, feels best when he’s by himself… when he’s solo.

What do you do once you establish your hero’s flaw? You place something in front of them that challenges that flaw. In this case, Alex gets the first serious girlfriend of his life, Sanni. Throughout the film, Alex talks about how, normally, he doesn’t tell anybody when he’s soloing. He just goes and does it. He isn’t afraid to die because… well, if you die you die. So what? But Sanni throws a wrench into that equation. Now, if Alex dies, he leaves pain and suffering. He emotionally destroys someone who loves him. Alex attempts to dismiss this, saying Sanni will be upset for awhile but eventually find someone else and move on. But when Sanni fights him on this, we get the sense that Alex is saying this to rationalize his solo’ing. If he’s forced to connect with others, it could mean the death of what he loves.

Bringing it back to screenwriting, a battle with one’s flaw creates conflict inside the hero just as compelling as the conflict on that mountain journey. Will Alex back down now that he has someone who cares about him? Or will he continue to put himself first? Continue to ride solo?

This brings up another thing Free Solo does well, which is incorporate Alex’s friends into the movie, all of whom have deep reservations about Alex free soloing El Cap. The director of the movie is one of Alex’s best friends. He’s conflicted about the project because he could be documenting his friend’s death. Alex’s mentor (who, coincidentally, is the star of that other climbing movie I mentioned above) thinks Alex is in over his head with this one. He’d be happy if Alex let it go.

The reason bringing these characters in is important is that they act as emotional multipliers. The more people who care about our hero’s success, the more people we’ll be happy for when the character “wins.” It isn’t just Alex we’re ecstatic for. It’s his girlfriend. It’s his mentor. It’s his best friend. Ironically, we don’t feel that same level of emotion if Alex has no one in his life and does this alone.

As I close this out, you’re probably wondering about Urgency. Free Solo’s got a great G. It’s got an even better S. But what about the U? They focus on urgency a little bit in the film. If Alex doesn’t climb El Cap by the end of the season, it’ll be winter and they’ll have to wait until next year. But the truth is, if you have a goal and stakes that are THIS STRONG, the urgency doesn’t have to be perfect. Especially if you’ve also got a compelling character at the center of the story, which Free Solo does.

If you haven’t seen this film, I recommend it. Let it become the metaphor that drives all of your screenplays moving forward. An impossible mountain to climb where the stakes are sky high.

We are almost at the end of the First 10 Pages Challenge! You have until Sunday, 11:59pm to submit your entry. Send a PDF of your pages to carsonreeves3@gmail.com with the subject line “FIRST 10 PAGES.” Head over to the original post to find out more about the challenge and what I’m looking for. I’ll let you know Monday (after I see how many entries I get) when – or IF – a winner will be announced. It’ll likely be no longer than a month.

Here are five of those entries. For those of you new to First 10 Pages breakdown posts, what I do is take five entries, show you how far I got, and explain why I stopped when I did. I’m hoping this information helps you craft your pages in such a way that they’ll be impossible to put down, which is the name of the game. Let’s get to it!

It’s never good when I’m confused by the very first slugline. I don’t know what “Tenement back-courts” are. Tennis courts? Basketball courts? As a writer, you never want to assume that the reader knows what you’re talking about if it’s in any way specific/unique. If I’m describing an area in Los Angeles and I say, “The Hollywood Sign,” you know what I’m talking about. If I say, “The Bird Streets,” you probably don’t. So I need to tell you what that is.

It’s important to talk about what the writer does next because it’s risky. And if it doesn’t work, you can lose the reader right away. The writer talks AROUND the setup instead of just setting the scene up. In other words, he doesn’t say, “VEA GREY searches through hanging laundry, looking for the perfect outfit.” He says, “GOLD-BROWN EYES. Searching. A scar on the bulge of her cheekbone. Tough times, but VEA GREY’S been tougher.” We’re talking AROUND the action, AROUND the introduction of the character, instead of just setting things up normally.

An argument can be made that this scene is set up like a movie. It’s almost like we’re a camera and we’re meeting this person, as well as what she’s doing, image by image. Unfortunately, a lot of readers don’t like this, myself included. We’d rather you just tell us what’s going on. I had a hard time understanding what I was looking at, so I was already on edge. And once we get to the arcade, my mind has drifted, and I’m out.

Let me remind you of the point of the exercise. It’s to hook the reader immediately. Not get all artsy-fartsy and try to impress the reader. That never works.

These pages were okay. I like the paranormal ghost hunter sub-genre, so I gave the pages a little longer than I normally would. That’s something you can’t control as a writer – if the reader likes your subject matter or not. The only thing you can do is send your script out to as many people as possible, increasing the odds that more people who enjoy the genre will read it.

There just wasn’t a big reason for me to keep reading here. The teaser was unique, which I liked. But once we got to the ghost hunting scene, it felt too familiar, and sloppy to boot. There wasn’t enough structure to the scene. What the writer should’ve done is set the scene up from the start. Build the scene like a mini-screenplay, with an Act 1, Act 2, and Act 3. Actually, that’s my best advice to pull a reader in right away, is open with a scene that’s a mini-story within itself. This is exactly what they did with Inglorious Basterds. It’s what they did with Scream. It won’t work for every script. But if there’s even a chance it will work for yours, consider it.

Oh yeah, and get a proper screenwriting program! Readers have been known to blacklist writers with text this light.

This scene moves too fast. Remember that hooking a reader doesn’t mean racing through a scene at breakneck speed. In fact, it can mean the complete opposite. In the case of this script, my first question is, why are they here? They’re driving through this place – Wildland Ranch – that appears to be special, like a backwoods Disney Land. Yet they don’t appear to be going here. The way they’re talking to each other, you’d think they were on their way home. It’s odd.

Then, when this woman pops out of nowhere, everything occurs way too fast. When something this jarring happens – a woman appears in front of your car out of nowhere – you need to take your time. It takes all of three lines from “My baby’s missing, will you help me,” to our heroine agreeing to. I mean come on. We’re in the middle of nowhere. This woman seems off. There would be questions. Erin and Roy would probably fight about it awhile. Bottom line: The writing feels rushed. It doesn’t seem like the writer has thought through the scenario. And for that reason, I’m out.

There is absolutely nothing wrong with these pages. Nothing. But there’s nothing exceptional about them either. Let me remind you what the exercise is again. It’s to hook the reader. It’s not to write something that’s “fine,” or even “ better than fine.” It’s to GRAB THE HELL out of the reader and make it impossible for them to stop reading

Starting your script with a murder is an above-average opening scene choice. A dead body gets the juices flowing. We’re curious who this is, what happened. A goal is set up right away – solve the murder. The problem is, I’ve read hundreds upon hundreds of scripts that have started with a murder. What makes this different? That she’s a celebrity? I’ve read tons of celebrity murders as well.

You have to find a way to make your scene unique. Here’s the opening of an early draft of Silence of the Lambs, which covers another familiar setup – an agent engaging in a dangerous hostage situation. Ignore the bold text. Someone did a bad digital PDF transfer from the original script.

Would you keep reading? I would. Notice that by making a slight tweak – the unexpected reveal that the suspect’s finger is taped to the trigger in a manner where he’s unable to use it – gives the scene a fresh feel (not to mention puts our hero in serious danger). Remember, the audience has seen everything. You need to work your ass off to give them something they haven’t.

Wow! I made it to the end of another ten pages. Sweet! Okay, why did I read all ten of these pages? There’s nothing spectacular here. But much like Bill’s pages from last week, there wasn’t any reason to STOP READING. The writing is achingly simple. And that’s a good thing. Unlike the first entry, I’m not trying to piece together the simple actions of my main character. Everything is clear as day.

Another thing is that in all the scripts I’ve read, never has one started with a woman teaching immigrant women how to wear their bathing suits properly so they don’t get arrested. The value of originality in a world so saturated with content is high. That’s why I read past the first page.

The writer then shifts to a marriage ripe with conflict. It’s not over the top but we sense it in their phone call. Remember that when you establish conflict, there is a subconscious need for the reader to keep reading to see if that conflict gets resolved (if she smiles and says “okay,” there’s no mystery to this marriage). From there we get this fun little wallet-stealing fiasco where we’re wondering if Alice is going to come out victorious or not. What a great character, too. Who doesn’t like a woman who puts her reputation on the line to do what’s right?

I have to admit that I don’t know where this movie is going from here. But I like this feisty main character so I’m keen to find out. What did you think?

Genre: Action Thriller Sci-Fi Romantic Comedy

Premise: Barret is a social media influencer, the worst guy ever, and the eventual President of the United States. Dixie is a badass freedom fighter, sent back from 2076 to kill him before he takes over the world and ruins the future. They fucking hate each other. Then they accidentally fall in love.

About: This script finished Top 10 in last year’s Black List, a surprising showing considering the main character isn’t a real person (biopic joke). Michael Daldron seems to thrive in the absurd. He was a writer on the bonkers Dan Harmon TV show, Rick and Morty.

Writer: Michael Waldron

Details: 104 pages

We’re going to keep the absurdity alive this week! Yesterday, we covered a character who fell in love with a toe. Today, we explore traveling back in time to wipe out social media influencers.

What’s a social media influencer? I only found out the other day after watching Netflix’s Fyre Festival doc, a task I initially resisted because the media’s become a scourge of evil intent on destroying people’s lives regardless of whether they deserve it or not. I figured they did the same thing to this Fyre Festival dude. But ohhhh no. This guy deserved to be taken down. The crap he pulled would’ve caused a coma patient to stand up and demand action. I loved it so much I re-activated my dead Hulu account so I could watch their competing Fyre Festival documentary, which turned out to be even better than Netflix’s.

Anyway, all this is to say that social media influencers (the people who made Fyre Festival a “thing”) are vapid black holes of emptiness, the bottom rung of entertainment. And the current generation is growing up on them, which means they’re going to be the primary source of entertainment at some point. Get your Logan Paul merch while you can still afford it!

20-something Dixie lives in the year 2076, a post-apocalyptic future that is the result of a stupid douchebag of a social media influencer, The Duke, becoming president and ruining everything. After searching far and wide, Dixie locates a time-traveling backpack, and after killing the future version of Duke, goes back to the year 2018 to kill the young version of Duke so that he can never become president in the first place.

Dixie arrives in 2018 and immediately attacks the young Duke (who’s simply named “Barret” here). But within seconds of the attack, a 16 year old Duke disciple, Miller, also from the future, appears in a jet pack and attacks Dixie. Dixie and Miller battle while the confused Barret watches on, tweeting and instagram storying his fans about the attack.

Barret hops in a car and drives off, but Dixie easily catches up to him. When she finally has a clear shot to take him out, she waivers. This Barret may be a nimrod, but he’s far from the megalomaniacal super-douche that runs the country in 2076. After he pleads for his life, Dixie compromises and gives him a last dinner, which they share at Chuck E. Cheese. Unfortunately, the more Dixie talks to Barret, the more she kinda likes him. And by the end of the meal, she decides to postpone the assassination for a little longer.

The next day, Dixie comes up with another plan. If Barret walks back his earlier posts about running for president, he’ll never become president, and the future will be saved without Dixie having to kill him. But this comes with a new problem. If he does this, Dixie will disappear, since the future will completely change and she’ll have never been born. Since the two are starting to like each other, they postpone this ‘not running for president’ post a little longer.

The next thing you know, the two are living together, Dixie is pregnant, and Barret spends his downtime traveling back in time to World War 2 trolling Nazis. When Barret learns that Dixie already killed the future him before she jumped back in time, the two get in a fight and Dixie takes her time-travel backpack, jumps back 65 million years, and starts training velociraptors to talk. I could go on but does it really matter at this point? More time travel. More fighting. The two live happily ever after. The End.

I used to get mad at these scripts – when the comedy is so absurd it takes precedence over plot and character. But now I realize different people think different stuff is funny and while I may not have liked it, younger audiences who don’t put a premium on logic and plot progression will probably enjoy it for the same reasons I didn’t.

I do think a world where Logan Paul is president is a funny setup. My issue is that these types of setups are great for a 22 minute episode of Rick and Morty, but become tiring stretched out to two hours. And you can see that play out as you’re reading the script. Once Dixie and Barret enter into a relationship (about 50 pages in), it’s clear the writer doesn’t know where to go. So he goes everywhere. I mean at one point we’re 65 million years in the past listening to a deep conversation between Dixie and velociraptor.

At times, Waldron’s script almost becomes the thing he’s making fun of. Here we are blasting narcissistic millennials obsessed with Instagram stories yet half the script is written in CAPS while being self-referential and breaking the fourth wall (for example, when a fight occurs, we’re told that it will get nominated for an MTV Movie Award for Best Fight). If that isn’t the screenplay equivalent of a douchey influencer posting an Instagram story, I don’t know what is.

I also think there’s a bigger discussion here about writing a script that’s trying to be fun and writing a script that IS fun. When you’re having fun, it comes off on the page. But when you’re TRYING to write that viral fourth-wall breaking screenplay, it can come off as try-hard and your script quickly goes from cool to lame. Deadpool constantly walks this line and one can make the argument the sequel crossed it. You could feel it desperately trying to make you laugh, instead of trusting its story so that the laughs came naturally.

The one thing I’ll give this script is that, just like yesterday’s screenplay, I didn’t know where it was going. I was dreading a 105 page wall-to-wall comedy action flick where Dixie tried to kill Barret the whole time. That’s what most writers would’ve done. One of the most boring things you can do is to hit the same beat over and over again in a screenplay. You have to come up with clever ways to spin the story in different directions so the plot stays fresh. And Waldron achieved that. I was surprised when these two got together. And I didn’t know where their relationship was going to go from there. I think it says a lot about how much readers value unexpected plotlines that both this and The Toe finished highly on the two big End of the Year lists.

In the end, however, this isn’t my thing. I can throw all the screenwriting gobbledygook at you I want to explain why I didn’t like it. The truth is that when we don’t like something, we can come up with a million reasons why. This script was too juvenile for me. But it’s probably just the right flavor of juvenile for someone else.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Remember that the more words and sentences you cap in a screenplay, the less impact those words have. They become just as normal as uncapped words. Understanding, then, that the point of capping something is to bring to attention to it, use it sparingly, so that you can actually draw attention to the action you want to draw attention to.

Genre: Sci-Fi/Interactive

Premise: In 1984, a young programmer, determined to create the best video game ever, begins unravelling during the programming process when he suspects that an unseen force is dictating his actions.

About: How cool it is to be Charlie Booker? You’ve created a show that allows you to tell ten new science-fiction movies a year. I’d sign up for that every day of the week. Today’s film, like a lot of Netflix titles, came out of nowhere, arriving on the service the last week of 2018. Its choose-your-own-adventure narrative has created a lot of discussion – some negative, some positive. But everyone seems to agree that it’s worth talking about. Bandersnatch was directed by David Slade, who has an interesting Scriptshadow connection in that he’s attached to direct, “Meat.”

Writer: Charlie Booker

Details: 90 minues

Choose-your-own-adventure stories were always more appealing in theory than they were in practice. Even as an easily entertained kid, I remember awkwardly jumping back and forth through these books and feeling like I was doing a lot of work for not a lot of payoff.

So I was skeptical when Black Mirror announced a choose-your-own-adventure movie. It’s hard enough to write a screenplay using all your best choices. Multiple-choice narratives force the writer to incorporate options he wouldn’t have otherwise chosen. Which begs the question: How do you write a good story if you’re not always using your best stuff?

But Black Mirror is the one property I’d trust with this setup. Their brand is designed to take chances and, more specifically, incorporate technology into the story. The rules are simple. Every 5-10 minutes, a character will ask a question (Therapist: “Do you want to talk about your mother?”), and two choices will appear on the bottom of the screen (“Yes” or “No”). An unobtrusive white line appears, casually shrinking inward, signifying the amount of time you have to make your choice.

The central storyline of Bandersnatch places us in the year 1984. 20-something game programmer Stefan Butler wants to turn his favorite choose-your-own-adventure book, Bandersnatch, into a video game. He interviews at the best company in town, Tuckersoft, where his programming hero, Colin Ritman, works. The president loves the Bandersnatch pitch and asks Stefan to develop the game.

Quickly, however, Stefan runs into gamer’s block. Something is missing to bring the game to that next level. Part of the problem is Stefan feels like he’s being controlled. Seconds after we’re asked whether we want Stefan to bite his nails and we answer yes, Stefan slams his hand down, refusing to engage in the activity. A new theme begins to permeate the story – that of free will. Stefan doesn’t believe he has it.

Stefan eventually goes to Colin for help with his gamer’s block, and Colin regales him in a story about how Pac-Man is a metaphor for how we’re all stuck in a maze, consuming, with no way out. The good news is, we can jump to parallel realities to alleviate the resulting insanity. Colin insists that they both get high, and we know Booker wanted this scene because we don’t get the option to say no. After they get really high, Colin suggests jumping off his high-rise to prove his parallel realities theory. We get to choose which of them jumps. I chose Colin, who jumps and dies.

The trippiest moment in Bandersnatch occurs when Stefan starts screaming to the skies that he knows someone is controlling him and wants to know who they (you) are. We’re given the choice of saying “Netflix” or a story relevant symbol. I couldn’t resist choosing Netflix, which results in “me” explaining to Stefan that I’m from the 21st Century watching him on Netflix and controlling his actions.

When Stefan brings this up to his therapist, she replies, “If you were really in a movie, wouldn’t there be more… action?” The movie then asks you if you want more action (you can only answer “yes”) and the two proceed to beat each other’s ass.

Stefan goes deeper down the rabbit hole, embracing the insanity of what’s happening to him, which results in him brutally murdering his father (or maybe I was responsible for that, since I told him to). Eventually, he creates the perfect game, which becomes a cult hit that 35 years later is turned into a Netflix show.

Ten minutes into Bandersnatch, I suspected I’d stumbled into a big waste of time. I’m choosing which cereal Charlie eats. Whether to talk about his mom or not. Borrrrr-ing. But the movie picks up once we start breaking the fourth wall.

One of the things I keep telling you guys it that when you come up with a concept, you want to explore everything you can that’s unique about that concept. Most writers don’t do this. The concept is their way into the story. But once they’re in, they write a bunch of characters and scenarios and action that we’ve seen before. If you’re going to make a “choose your own adventure” movie, you want to ask what you can do with that format that hasn’t been done with traditional movies before. If all you’re going to do is offer the viewer a bunch of fake choices that lead us to the same ending, there’s no reason to make the film.

By connecting you directly to the characters to the point where they’re recognizing that you’re controlling them fully immerses us in the experience and makes Bandersnatch unlike anything we’ve seen before. I mean think about. You couldn’t do this five years ago, much less twenty years ago. There’s no way to do this in a movie theater since everybody’s choice would be different. And movie theaters don’t have the necessary technology to be real-time interactive anyway. So all that was great.

Was the story good?

That’s tougher to answer. I was engaged throughout the movie. But a lot of that had to do with the format. I started to enjoy the fact that I was controlling this person’s decisions, which made me more focused on that than whether character arcs were being fulfilled or the pacing was on point.

But the core plot point kept things focused. By setting up the goal of Stefan needing to create the game, we always knew where we were going. And it wasn’t just that. It was that Stefan was highly motivated. We could tell that this game meant everything to him. And that’s something that’s always going to supercharge a protagonist – if they’re obsessed with achieving their goal.

It also sounds to me like there’s a lot more to this show. Some people have been obsessively watching it and choosing every different direction so as to experience every version of the movie. I’d be interested to hear if your plot breakdown is different from mine. I suspect they can only offer so many alternative storylines, or else they’d be shooting for years. But I’d love to hear if someone watched a completely different movie than I did.

That’s what’s so cool about this project. It’s different. And not only different. It took a gimmick and it did something with it. The gimmick didn’t stop at the conceptual phase, which is what happens with so many gimmicky ideas. All in all, Bandersnatch was a refreshing film. I was pleasantly surprised.

[ ] What the hell did I just watch?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[xx] worth the stream

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: While it kind of worked here due to the unique format, I strongly discourage writers from using the “Kid’s Mistake Led To Mommy/Daddy’s Death” flashback. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve read this trope. Let’s get rid of it once and for all.