Shorts Week Continues: Welcome to Day 4 of Shorts Week, where I cover 5 short scripts from you guys, the readers. Shorts Week was a newsletter-only opportunity. To sign up and make sure you don’t miss out on future Scriptshadow opportunities, e-mail me at the contact page and opt in for the newsletter (if you’re not signed up already). This week’s newsletter went out LAST NIGHT. Check your spam folder if you didn’t receive it. If nothing’s there, e-mail me with subject line “NO NEWSLETTER.” You may need to send a second e-mail address.

Genre: Drama/Thriller

Premise: A sinister man on a bus receives a powerful valentine from a little girl.

About: Today’s short has already been turned into a short film. It was submitted by longtime commenter, Jaco.

Writer: Rob Burke

Details: 2 pages

So far we’ve read a strong animated short, a strong CGI-heavy short, and a live-action script which I used as an example of what not to do in the shorts medium. What we haven’t read yet is a short that we can actually COMPARE to the finished project. Well that’s going to change today. We’re not only going to read a short, but we’re going to see what it looks like on the big screen (or your small screen).

I actually saw this short before I read it. Rob tweeted it to me a few months ago. I thought it was good. Nothing earth-shattering. But something you remember. And in a world filled with mostly forgettable stuff, that’s saying something.

It was interesting, then, going back and reading the script, because there were some key differences between the two. Those differences are worth discussing as they had more of an effect on the final product than I think Rob knew.

“Love” begins with a man, 38, wearing a backpack, waiting for the bus. This isn’t a friendly fellow. He isn’t the kind of guy you’re going to invite to your son’s Bar mitzvah. He’s a mean looking dude. Nervous, too. He’s clearly up to something.

He wasn’t always this way though, as a quick flashback shows. He once had a wife, a baby boy. He was once happy.

The bus arrives. It’s full. This seems to bring satisfaction to the man. Once on the bus, he sits down, takes a look around. Lots of people, going about their daily lives. Another flashback. More time with his family. A little girl across from him breaks him out of his trance with three simple words: “Happy Valentine’s Day.”

She offers the man a valentine, a little red heart with the word “love” on it. The man takes it reluctantly, bringing a smile to the girl’s lips. But he’s still got a job to do. He stuffs his backpack under the seat and slips out the door at the next stop.

Another flashback – the aftermath of some sort of explosion. His family has been killed. Devastation. Fear. Anger. As he watches the bus drive away, he pulls out a phone – HIS DETONATOR. The valentine slips out of his pocket, floats in front of him. One more look at the phone. Should he press it? Just as he’s about to, he changes his mind, throwing the phone away instead.

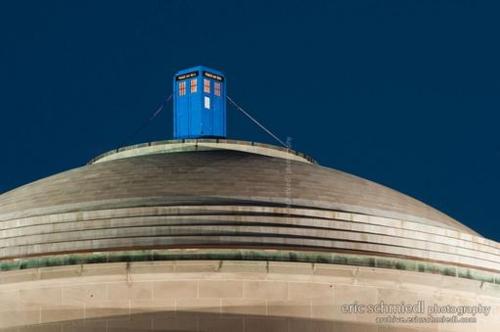

Now let’s take a look at how the movie turned out…

As you can see, there were some key differences. First, the bus was changed to a subway. I’m guessing this was done because it was easier to shoot, but it ended up being a better decision. There’s something scarier about this happening underground in a subway setting.

The flashbacks have also been eliminated. I’m guessing this was also a budgetary decision, but this really hurt the short in my opinion. Those flashbacks are the only way into our main character’s head. And in this case, they told us a ton. They told us he used to be happy, that somebody was responsible for the death of his family, and therefore this is probably payback. It’s not that we WANT this guy to succeed, but we at least understand why he’s doing what he’s doing.

The next change was a creative one, and I think it really hurt the film. In the script, the girl gives a Valentine only to him. In the film, he looks around to see that she’s given a Valentine to everyone. I don’t know what this choice was supposed to achieve but the way I saw it was that he wasn’t special. Her desire to give him a Valentine basically meant nothing since everyone else got one as well. In the script, this moment was much more special. It meant something because she targeted only him. Combined with the flashbacks to his family, it shows a man who’s able to feel again, which is likely why he didn’t pull the trigger in the end.

The final big change is the ending. In the script, he doesn’t pull the trigger. In the movie, it’s open. We see him hovering over the detonator and cut to black before a decision is made. To be honest, I don’t have an opinion either way on this. I don’t know if that’s good or bad but as long as he didn’t blow that cute little girl to bits, I’m okay with it.

So how does “Love” hold up overall? Well, here’s what I took away from it. First, it’s possible to tell a big story in a very short period of time. This script was just 2 pages long. TWO PAGES! And in that time, a LOT happened. We had a guy waiting for the bus. We saw moments from that character’s past. We had him get on a bus. We had him making a connection with a little girl. We had him leaving a bomb on the bus. We had him getting off the bus and trying to decide whether to detonate the bomb. That’s over 4 locations in 2 minutes!

Compare that to a lot of these shorts I’ve been reading that just seem to go on forever in the exact same location with very little (to no) progress in the plot. “Love” teaches you how much you can do in a very short amount of time.

Having said that, there’s something missing for me. I’d probably still give it a passing grade because Rob fit such a big story into such a small package, but ultimately the stuff that happened on the bus was too muddled. In the script, I’m not entirely sure what happened to the protagonist’s family. I think that’s important to know. And in the movie, I’m not sure why you’d give everybody in the bus a Valentine instead of just our protag. While watching that moment, I thought for sure there was some bigger meaning to what was happening. But then I realized it was just…he’s one of many people who got a Valentine. Because I couldn’t figure out what the intention was of that decision (it looks like it’s supposed to make him happy seeing all these valentines, yet logic would tell us that the opposite should happen), I had to dock it a few points.

So a solid effort, but I feel that Love had the potential to be something much bigger.

Script link: Love

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Just showing a character’s reaction to things isn’t enough, especially in a short, where we don’t have any time to get to know the character. We need a way into their head. We saw this Tuesday with “Tigers.” Emma had Hobbes to talk to, which allowed us into her thoughts. And we actually saw it here in the script, with the flashbacks. However, once those flashbacks were erased for the final film, you saw how difficult it was to know anything about the protag or what he was thinking.

Shorts Week Continues: Welcome to the third day of Shorts Week, where I cover 5 short scripts from you guys, the readers. Shorts Week was a newsletter-only opportunity. To sign up and make sure you don’t miss out on future Scriptshadow opportunities, e-mail me at the contact page and opt in for the newsletter (if you’re not signed up already). No, this week’s newsletter still hasn’t gone out yet. But for SURE it will go out tonight. If you don’t get it, make sure to check your SPAM FOLDER. If it’s still not there, let me know tomorrow morning.

Genre: Drama

Premise: A young man struggles with having to face his best friend for the first time since his failed suicide.

Writer: Dan Sanek

Details: 9 pages

So far, I’ve been talking about what works in a short script. However, we can’t learn everything if we’re only covering the good. In order to get the most out of Shorts Week, we must also take a look at what DOESN’T work. Now I didn’t want to put anybody on the spot here, but in order to do this properly, I have to put someone on the spot.

As I said, the shorts that are real killers are the ones where two people are in a room talking. I’ve read a lot of these. Here’s the surprising thing though: A lot of these shorts (including this one) AREN’T badly written. You don’t, at any point, say, “Oh my god. This is terrible writing!” It’s simply that the SITUATION isn’t interesting. Our writer may think it holds weight because death is being discussed, and death is a weighty subject, but here’s the easiest way to judge whether you’ve written something worth writing: Is anyone going to recommend your short movie to anyone else? Is anyone going to see this and say, “Oh man, you gotta see this short about two guys talking about suicide!” The answer is no. Nobody is. Even if you write the PERFECT VERSION of this screenplay. So no matter how deep you think it is, it doesn’t matter because nobody’s going to want to see it.

A short HAS to have something hook-y about it. It has to have SOME aspect to it that’s going to get people to tell others, to trade it around. Otherwise you’re just practicing how to work a camera and direct actors.

Art Imitates Life begins with a young man, Art, trying to slit his wrists in the bathtub. He succeeds with the slitting part. But apparently doesn’t slit hard enough to achieve the ultimate goal – to commit suicide.

A few days later, after recovering, Art visits his best friend, Max, who works at an art gallery. This is the first time they’ve spoken since the big attempt. Max is a very non-suicidal type, so he’s not sure how to approach this. He makes a couple of awkward jokes, attempting to lighten the mood, and Art seems to enjoy the casual atmosphere. They even make light of the fact that Art’s mom follows him around everywhere because she’s afraid he’s going to try again. She’s even waiting outside for them to finish so she can drive Art home!

But after awhile, Max wants answers. Why’d he do it? Or why’d he TRY to do it? I mean could things really be that bad? Art explains that he just didn’t see the point in anything anymore. Not exactly the most profound reason for killing one’s self, but hey, there’s no rule that says you have to be profound when committing suicide.

In the end, Max is just happy that his friend is okay. The two say their goodbyes. They’ll see each other soon. Art jumps in his car with his mother and she asks him what he wants for dinner. Art says anything is fine. He just wants to take a quick bath before he eats. Pan down to see Art has stolen……..A BOX CUTTER from Max. Looks like Art isn’t done with his little side project after all.

Okay, a couple of things here. I’m not saying that suicide isn’t something worth discussing. I’m not saying there aren’t people out there dealing with the same problems as Art and therefore people who won’t relate to this subject matter. But by and large, people are going to see this as, “The short where two guys sit in a room and talk about suicide.” It’s depressing. It’s boring. There’s nothing unique or special about it.

If you really want to explore suicide in a short film, find a bigger canvas to do so. Not only will you get to tackle your serious subject matter, but you’ll get to do so in a way that excites others. Irony is one way to do this. What if, for example, your story centers around a zombie who wants to commit suicide? A zombie’s already dead. Zombies aren’t supposed to think about suicide. Which all of a sudden makes your short unique, different. Or maybe a robot wants to commit suicide. It could even be a humanoid robot to keep the budget down. Again, robots aren’t supposed to want to commit suicide. They’re not human enough to deal with it. This allows you to play with serious subject matter but on the kind of canvas that’s going to get a lot more people interested.

It’s no different than what a movie like, say, District 9 did. Sure, they could have made a straightforward film about apartheid, about segregation and discrimination. But that ultra-serious uber-pretentious film would’ve made about 10 bucks at the box office. You had all these deep things to say and yet none of them mattered because no one came to see it. By using alien segregation as a metaphor for real-world discrimination, however, you now get to explore the complicated subject matter of discrimination in a much more audience-friendly format.

Another way to play with irony is to have your characters discuss the deep troubling subject matter of suicide in an environment that’s COMPLETELY THE OPPOSITE of suicide. For example, why not write a comedy short where Art, Max and their dates are at a football game? The environment is exciting and full of life. It just so happens this date was set up before the whole suicide attempt and Art and Max haven’t had a chance to discuss the attempt yet. So in between plays, while the girls are talking amongst themselves, Max is discreetly asking Art what the hell happened. Why did he try and off himself? The midpoint twist could be the girls overhearing them and Art having to come clean. Art is being depressing and a total downer amongst thousands of people cheering and having the time of their lives. Again, irony makes this situation a lot more interesting than two people in a room talking about how life sucks all by themselves.

But even if you strip away all that and just look at this as a simple short about suicide, I still don’t think it works. Whenever you’re tackling something as ubiquitous as the subject of suicide, you NEED TO GIVE US SOMETHING NEW TO THINK ABOUT. If all you’re going to do is rehash a common argument, then there’s nothing for us to sink our teeth into. We’re basically told that Art wants to commit suicide because, “life sucks man.” Well yeah, we’ve already heard that reason a billion times before. Instead, try finding new angles to old subject matters. Make us see the subject in way we haven’t before. For example, instead of Art being depressed, maybe he’s the happiest person on the planet. He loves his life. He lives every day to the fullest. He sees suicide as an adventure – he wants to see what’s on the other side. I’m not saying this is the best idea. The point is – IT’S DIFFERENT. You’re attempting to see the subject matter in a way that hasn’t been explored before. Think about it. If all you’re doing is writing/shooting something that’s already been said thousands of times, what’s the point?

Two people in a room talking about “serious” subject matter is almost always a recipe for disaster in the short world. Even if it’s well written. My advice is to think bigger. You have to stand out with your short somehow.

Script link: Art Imitates Life

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: It doesn’t matter how good of a writer you are if you’ve picked boring subject matter. Never forget that, whether it be in creating a short or in creating a feature.

Shorts Week Continues: Today is the second day of Shorts Week, where I cover 5 short scripts from you guys, the readers. Shorts Week was a newsletter-only opportunity. To sign up and make sure you don’t miss out on future Scriptshadow opportunities, e-mail me at the contact page and opt in for the newsletter (if you’re not signed up already). No, this week’s newsletter still hasn’t gone out yet. Hopefully by tonight!

Genre: Horror/Zombie

Premise: (from writers) A lone survivor in a world besieged by the undead struggles to protect her home: A big cat farm in the middle of Iowa.

About: These two won the very first Scriptshadow Screenplay Contest with their script, “Oh Never, Spectre Leaf!”

Writers: C. Ryan Kirkpatrick and Chad Musick

Details: 23 pages

I remember there was a time when shorts were pointless. The only way a short could actually help your career was if it somehow got picked as an Oscar nominee. And who the hell knows how that happens? Win a couple of major festivals? I mean talk about a system that didn’t give you a lot of bang for your buck.

Youtube has changed all that. Shorts are one of the most promising ways to start a career in filmmaking nowadays. I mean, Scriptshadow fave “Mama” started off as a short. Had Guillermo Del Toro not seen that thing and loved it, we would’ve never met that floaty-haired little freakshow in feature form.

And even without the super-success stories of visual-effects whizzes launching their careers via jaw-dropping short films (Neil Blomkamp), shorts on the internet are still a must for any young filmmaker. I mean, when someone tells me he’s a director these days, the first thing I do is look him up on Youtube so I can watch one of his shorts, see what he’s about. If he doesn’t have anything up, I don’t take him seriously. It’s practically a requirement.

So it’s an intriguing transition. Shorts have gone from completely insignificant to the number one calling card for young directors in all of 7 years. Oh, how fast the business changes. However, shorts are still being produced via the wrong approach. They’re typically generated by directors trying to show off their stuff. This is NOT the way you should approach a movie. First and foremost should be the script. The script has to be a story worth telling.

If we could develop a shorts system that marries writers with directors somehow, my guess is that shorts would be a lot better. But the importance of the system has grown faster than the system has been put in place. Of course, writers aren’t really prepared for this either. If the shorts I’ve been reading are any indication, screenwriters aren’t really sure how to tackle this new blossoming medium. There’s still too much boring subject matter and boring storytelling. A short film has to be both emotionally satisfying AND memorable/different in some way. It has to STAND OUT. Which is a perfect segue into today’s offering.

30 year-old Emma Gray hasn’t been having the best week. She’s had to kill her husband after he turned into a zombie, and upon doing so, upset her little boy so much that he ran away. The only thing left in her life is her son’s childhood stuffed animal, Hobbes, who she’s taken to talking to (a la Wilson from Castaway) in order to prevent insanity.

After dusting a few zombies of the 28 Days Later variety (frantic runners), Emma decides to go back to her childhood home, where her family (I believe) owned a veterinary clinic. But not just any veterinary clinic. This clinic took care of big cats – tigers, leopards, cheetahs, that sort of thing. When Emma goes to check on how the animals are doing, she learns they’re not so good. Apparently the zombie virus has crossed into the cat world. And that’s not good news for anybody planning to take a stroll into the cage room.

Once the zombie tigers spot Emma, they go nuts, bursting out of their cages. Emma has to put them down Old Yeller style (by the way, why did they make us read that shit when we were kids? Who wants to read a story where a dog is deliberately killed?). Pretty soon, a few bullets aren’t going to do the trick. There are zombie tigers everywhere, and she’s gotta exit the premises, pronto.

So she grabs Hobbes and away they go, following the directions of a radio transmission that promises safety for survivors. Unfortunately, her car isn’t going to make it on a dwindling tank of gas, so she has to stop at a gas station. After she grabs some supplies, she’s shocked to find the door to her jeep open and Hobbes gone! Hobbes being the only thing keeping her sane, she hops in the car and goes after the thief, a zombie trucking through the forest. She leaps out, shoots him dead, and walks over to grab her stuffed tiger. But when she sees who she’s killed, her entire world falls apart…

As Keanu Reeves would say – whoa. This was one hell of a trip. First thing I wanna mention, though, is the length. Despite the quality of this and Friday’s script (which is also 20+ pages), I don’t think these feel like traditional shorts. They feel like shorts-plus. 20+ pages is more than a casual commitment and therefore Shorts-Plus scripts are going to be harder sells for people. I’m guessing not as many of you are going to read this based on length alone. I don’t want to make some definitive statement or anything. But length clearly matters. It will affect your reads. Lots more people are going to read a 7 page short instead of a 20 pager, regardless of how good it is. You’ve been warned.

As for the story itself, it had some good things going for it and some not-so-good things. Zombie tigers. Wow. That’s a crazy choice. It’s unique, but I’m not sure how many people will suspend their disbelief to buy into a story about zombie-tigers. I suspect some readers are just going to say, “That’s too weird.”

However, it’s also what sets this apart from all the other shorts. I think one of the key things you have to ask yourself when writing a short is, “Is this the kind of thing that people would tell other people about?” Is it the kind of video where people will say, “You gotta see this?” Would they put it in their e-mail? Would they tweet about it? Otherwise, what’s the point? You’ve made a short for you and your buddies. Who cares? Zombie tigers and cheetahs trying to rip humans to pieces? If done well, that’s something I’d wanna see. So “Here There Be Tigers,” passes that crucial test.

Another key element that this short has going for it is the ending. That’s one thing I’ve noticed about shorts. The ones with surprise endings leave more of an impact and are therefore more likely to be shared. (Spoiler) Here, the person who stole Hobbes and is shot dead turns out to be (in case you hadn’t guessed), Emma’s son. Ouch. That’s a killer. It’s a nice twist if a little confusing. I understand it’s dark out, but if it’s bright enough to properly aim at someone’s head, wouldn’t you notice the difference between a 5 year old boy and a full grown adult? I wish that would’ve been more believably handled.

The Castaway effect was also a smart move. By providing this inanimate object (Hobbes), it allowed us to get inside our character’s head via her talking out loud to someone. Yesterday we talked about the power of a silent short (showing and not telling) which is basically what this is except for that little cheat – Hobbes. It was kind of the best of both worlds in that we still got to hear our hero, but only when we absolutely needed to. Overall, we still got that “silent film” feel.

There were a couple of things that threw me about “Tigers” though – the biggest of which was why the hell Emma would deliberately walk into a place with hundreds of wild tigers. Even if they weren’t zombified, that’d still be really dangerous. I got the feeling she went there (where home was) for some reason, but I couldn’t figure out what. Since the entire short is based on this premise, it can’t be an unknown. Her motivation has to be strong. So I’d like to see that strengthened in the next draft.

Also, there seemed to be some connection between her family and the cats, but that was also unclear. Were her family members all veterinarians? That would be my guess but it was still too vague. I wanted to know definitively why she knew the names of all the cats. And also, of course, why the hell she willingly walked into a veterinary clinic full of hungry animals.

In the end, there was definitely enough stuff to recommend Tigers. I just think some things needed to be cleared and tightened up. What did you guys think?

Script link: Here There Be Tigers

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: If you’re telling a story with a single character, consider creating an object that the character can talk to. Going completely silent for a film can be a real challenge. As we learned yesterday, there are certain things that are difficult to convey solely through images. Getting inside our hero’s head is one of them. If your protagonist has someone to talk to (like a stuffed animal), it’s a cheat that gives us that power.

Note: No, I have not sent out the newsletter this week. It’s been a busy weekend but I’m going to try and send it out tonight!

Genre: Animated (Pixar-ish)

Premise: (from writer) A lonely inventor builds a time machine, but finds it only works three minutes at a time.

About: Shorts Week was a newsletter-only opportunity. To sign up and make sure you don’t miss out on future Scriptshadow opportunities, e-mail me at the contact page and opt in for the newsletter (if you’re not signed up for the newsletter already).

Writer: Christy McGee

Details: 9 pages

So what makes a good short? It’s a question man has been asking since the dawn of time. “What is the meaning of life?” and then “What makes a good short script?” Unfortunately, there haven’t been a whole lot of venues to write short scripts, so the focus of them has been limited almost exclusively to directors who want to make short movies. They write short scripts pretty much by necessity. Oftentimes these short scripts are terrible, piece-mailed together to set a particular tone, get a particular shot or land a particular joke they love. Little to no focus has been put on the script itself.

Which is why you’re looking to me this week to give you the answer. You’ve spent your entire lives wondering how to write one of these things. If there’s anyone who should know how, it’s Scriptshadow. Errr, not so fast. I did Shorts Week for two reasons. One, there was an outburst of demand. People NEEDED this week for some reason. And two, I myself wanted to learn how to write a good short. I mean, there just haven’t been any situations for which I’d need to read shorts. So this was just as much an opportunity for me to learn as you guys.

Now I’m ASSUMING a good short, like a good script, has a setup (Act 1) a conflict (Act 2) and a resolution (Act 3). So that’s what I’m looking for. But honestly, I’m just looking for anything that stands out in some way. And that’s proven harder to find than you’d think. I’ve read a ton of bad shorts. The biggest issue I ran into was writers choosing ideas where not much happened. Lots of scripts had people sitting in rooms talking, almost like something you’d shoot as a student film to practice basic blocking techniques with actors. Nothing actually exciting, interesting, or different. The way I see it, you only have a very short time to tell your story in a short so it’s gotta stand out in some way. Normal and cliché are adjectives you want to stay as far away from as possible. With that established, let’s check out today’s short.

Luigi lives in the kind of small Steampunk town that I sure as hell wish existed in reality. He makes his living as an inventor and his latest invention is a backpack that allows him to travel through time. So excited is Luigi about his device that he’s called a town meeting to show it off.

Once everyone is at the town square, Luigi shows them an old newspaper with a picture of the square. He’ll go back in time and make sure to appear IN that picture to prove his contraption works. Luigi presses his magic time-traveling backpack button but…nothing. He presses it again. Nothing. People start to leave. He presses it a third time. Almost everyone has left. Luigi is devastated. Until he checks his watch. Wait, he actually HAS time traveled, but only 9 minutes backwards. People weren’t leaving. He’d just gone back to before they showed up! This means that his backpack is merely broken and only goes back 3 minutes at a time.

While not ideal, Luigi realizes he can still do a lot of good with his backpack. So he starts saving some cats, exposes some bank robbers, and offers instant replay to football games. Everything seems to be going swell until Luigi meets a little orphan girl who lost her mother to an accident while crossing the road.

Devastated, Luigi HAS to help this girl. So he does some research and finds the road where the woman was killed, but realizes it was an entire year ago. Since his backpack will only go back 3 minutes at a time, that means he’ll have to press it 178,776 times. Ouch. But if that’s the only way he can save this woman, then that’s what he has to do.

(spoiler) So Luigi heads back in time, saves the woman, and in the process falls in love with her. Cut to a year later and Luigi is part of the family: Mom, Luigi, and the little girl. He’s even created time-traveling backpacks for all of them and included them into his act. And this time when he gathers the entire town around, he’s ready. Or at least he thinks he is. When all three family members press their buttons, they, um…don’t exactly end up where they planned. To be continued.

The reason I liked this short was because it reminded me a lot of a Pixar short where the focus was on the storytelling and not on some boring dialogue exchange or some cool but ultimately thin sci-fi idea. “Time Well Traveled” was not only a rich storytelling experience, it was told without a single line of dialogue.

I realized that a ton of these shorts go on forever, like 20-25 pages, and yet they feel like nothing’s happened. We’re still in the same place on page 12 as we were on page 2. Yet “Time Well Traveled” feels like dozens of things have happened within that span. Clearly, this is the result of not including dialogue. Dialogue eats up pages because it takes up so much space. You wouldn’t notice that in a regular script at 110 pages long, but you certainly notice it with shorts.

I’m not saying that shorts should never include dialogue. But if you’re looking at this and my favorite short of the week (which I’ll review Friday), you’d be persuaded into thinking that the best way to tell a short is via images and not dialogue.

The thing is, when you’re not using dialogue, it becomes quite challenging to convey key plot points and really anything in the story that’s nuanced. Indeed there were some things that didn’t make sense to me on the first go-around that I had to read the script twice to understand. For example, I didn’t totally get, at first, that each press of the button only went back 3 minutes. Therefore when he’s trying to figure out how to save the mother and he comes up with the number “178,776,” I was scratching my head trying to figure out what that number stood for (Oh! I realized. That’s how many times he has to press the button).

Also, I didn’t read the logline. And it wasn’t until I did that I realized Luigi was “lonely.” That made the story more powerful since he finds this family at the end. But for that to work, we need some images or actions at the beginning that clearly depict how lonely Luigi was. I don’t remember that so it’s something I’d really focus on in the next draft.

There were a couple of other things, like when tries to save the falling cat and when he sits at the bus stop, that had me a little unsure of what exactly was going on. These are things that are easy to take care of in a dialogue-centered piece but quite challenging without, so it really takes some skill (and effort) to pull them off. In the end, however, these moments were few and far between and this short script easily stood out from the rest. It probably needs a clarity rewrite. And I wouldn’t have minded one little extra twist at the end (I always feel like time travel stories need a final twist). But other than that, good stuff!

Script link: Time Well Traveled

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: This script exemplifies the power of showing over telling. It also reminded me how much space can be saved if you show something rather than have characters tell us through dialogue.

What I learned 2: Make sure to be CLEAR when you are showing and not telling. It’s easy to assume that you’ve been super clever and conveyed what you’ve needed to convey through an image. But as this script showed, certain images or moments need extra clarity.

Today’s screenwriters take on MIT’s obsession with pranking. Is the script the next Real Genius or just a giant prank gone wrong?

Amateur Friday Submission Process: To submit your script for an Amateur Review, send in a PDF of your script, a PDF of the first ten pages of your script, your title, genre, logline, and finally, why I should read your script. Use my submission address please: Carsonreeves3@gmail.com. Your script and “first ten” will be posted. If you’re nervous about the effects of a bad review, feel free to use an alias name and/or title. It’s a good idea to resubmit every couple of weeks so your submission stays near the top.

Genre: Comedy

Premise: (from writers) An MIT reject crashes the school and discovers his greatest challenge isn’t getting caught by the administration — it’s surviving the high-tech hazing of a brilliant and jealous rival.

About: According to the authors, this script is inspired by true events. Every week I include 5 amateur screenplays in my newsletter and let the readers determine which one to review (sign up for newsletter here to participate). While the feedback for Crash Course was all over the place, it easily got the most interest of the bunch.

Writers: Steve Altes & Diana Jellinek

Details: 107 pages

I was actually discussing college comedies with a friend the other day and we agreed that if all you do is focus on the basic everyday drunken madness that is college, you’re going to bore your reader to tears. Just like any idea, you need an angle. Drunken madness at MIT? THAT sounds different. Even better when you focus on the unique world of genius pranksters. These guys don’t simply draw a penis on the university president’s picture. They download the picture, animate it complimenting Osama Bin Laden’s thoughts on his jihad, and play it on the basketball jumbotron in the middle of the homecoming game. No doubt, there’s lots of potential for comedy here.

18 year-old Jim Walden is making his way to MIT for his freshman year of college. Well, sort of his freshman year of college. You see, Jim’s not really a student at MIT. He’s a freeloader. Jim plans to get a degree at MIT without paying for it. He’ll go to all the classes. He’ll take all the tests. He just won’t be officially enrolled!

Jim quickly finds out that MIT is a campus full of pranksters. As in, when he makes his way past the main building, he sees that a car has been taken apart and reassembled on top of it (packed full of ping pong balls to boot). It appears that MIT students are so uninterested in doing real work (or so smart that they have tons of extra time on their hands) that they spend all their free time coming up with pranks. Whereas at the University of Texas, the receiver with the most catches might be the most heralded man on campus, here, it’s the guy who’s pulled off the biggest most complicated prank (or “hack” as they like to call it around these parts).

Jim soon finds his way into a local fraternity where he makes a bunch of new friends, plus reconnects with an old one, Luke. The group starts doing a bunch of “hacks” around school (that don’t really have much significance) and Jim is pretty good at them, which starts to make his old pal Luke jealous. At a certain point, word gets out that Jim isn’t really enrolled at the school, which puts all of the fraternity in danger, and gets everyone really mad at him. This delights Luke to no end, who doesn’t like playing second fiddle to anyone.

In the meantime, Nick meets a Shakespeare-obsessed young woman who works at a sperm bank. She helps him overcome all this newfound adversity, but soon she too learns of his lies and wants nothing to do with him. Eventually the story culminates in Luke having to pull off the ULTIMATE HACK at school, which I believe will make all his troubles go away.

Crash Course is a screenplay that FEELS fun. It has all the makings of a hit comedy. You got a bunch of goofy characters thrown into a bunch of goofy situations. Clearly, you’re updating some of those 80s classics like Revenge Of The Nerds and Real Genius. Which I think is a good idea. 80s comedies had an effortlessness to them that we haven’t seen for awhile.

But a few things crashed this course before it could get started, the biggest of which were the dueling concepts. You essentially have two ideas here. The first idea is about a guy illegally sneaking into college. Then you have the concept of a fraternity attempting to create the biggest “hack” of the year at MIT. Once you try to combine those two, the movie becomes confused. And that’s how I saw it. I was constantly trying to figure out what Jim sneaking into this school had to do with creating a giant school prank. Those two things didn’t organically fit together.

Not only that, but I couldn’t figure out how the “fake degree” thing made sense. Was Jim just coming to MIT to get educated or to get a degree? Because those are two different things. Just illegally taking a bunch of classes so you can learn I guess SORTA makes sense. But isn’t an MIT degree without an ACTUAL MIT DEGREE kind of worthless? You wouldn’t have any official documents to say you that you went to MIT which would severely limit your job options (in this case, becoming an astronaut). Which begs the question, what’s the point of going through this whole sham in the first place? And granted I didn’t go to a big university so I don’t know what it’s like, but I’m assuming it’s difficult to just sneak into a bunch of classes? And even harder to take tests? How does one take a test if they’re not even listed as a student?

A lot of people think this kind of stuff isn’t important since it’s a “comedy.” But it is. The details have to be solid. You can’t skim over the rules. If the rules aren’t clear, the stakes aren’t clear. Most of the best comedies come from stories with high stakes. We have to know what can be gained or lost in order to laugh. If I’m sitting there going, “Uhhh, so wait. He’s taking classes but he’s not really taking classes?” the whole time, I’m not going to be laughing.

The kind of fix you’re looking for here is one that simplifies the plot. First off, decide which is the more important idea to you. Is it a guy who fakes a college career or the MIT HACK plotline? I feel the MIT HACK plotline has a lot more potential so let’s go in that direction. Now create a plot that exploits that idea. This is admittedly hack-y since it’s off the top of my head but maybe Jim gets to MIT only to find out that his scholarship has fallen through. The school gives him a month to come up with this semester’s tuition, and if he doesn’t, he’s gone. His fraternity puts so much importance on winning the annual hack, that they say if he helps them win it, they’ll take care of his tuition.

That would be DRAFT 1 of the idea. You’d need to smooth it out and not make it so “screenwriting 101,” but that’s pretty much how most comedies work. Give your main character an important goal with high stakes attached within the context of a funny setting (in this case, sophisticated college pranking). Reading this draft of Crash Course, I kept forgetting what the point to everything was. He was trying to get an education. He was trying to help people create a great prank. But why? Why was it so important that he did these? So he could become an astronaut? I don’t know. I just didn’t care if this guy became an astronaut or not. It was so far away. A million things could go wrong between now and then that could derail his astronaut career (in other words, there’s no IMMEDIATE need for him to achieve his goal).

Most importantly, when the reader is focusing on all this unnecessary stuff or asking all these questions, or is confused about the purpose of the script – THEY’RE NOT LAUGHING. And that’s what you gotta remember as a comedy writer. If you set up an easy-to-understand plot with a clear protagonist goal, then you can have fun. Then you can throw all the jokes in there. Then your reader is going to be ready to laugh because they don’t have to think. They can just sit back and enjoy.

Look at the Hangover. They set up the situation – Friends needing to find the groom by x o’clock – and then just had fun.

Since too much of the plot and purpose and stakes were muddled here, I didn’t laugh that much, and obviously, you gotta laugh a LOT in a comedy – I’d say a reader should be laughing between 30-40 times out loud during a comedy-spec for it to be sale worthy. I do think this idea still has potential. A Real Genius update would be nice. But the plot needs to be simplified, as do the stakes and the protagonist goal. I wish Steve and Diana the best of luck!

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Comedy scripts should be the easiest scripts to read OF ALL THE GENRES. They need to be fun. I mean, of course they do – they’re comedies! So keep the prose sparse. Move things along quickly. Keep the reading style relaxed. And just have fun with it. Beware of overly technical writing or too much detail. Those things trip up and slow down a script, which you cannot afford when writing a comedy.

What I learned 2: Always beware of dueling concepts. Movies aren’t good at balancing two strong concepts. They tend to be best when focused on one thing. For example, The Hangover isn’t about guys looking for their missing friend in Vegas AND trying to win the World Series Of Poker tournament. Knocked Up isn’t about a couple trying to deal with an unplanned pregnancy stemming from a one-night stand AND the effects of their sex tape that accidentally got released to the public. In my opinion, you gotta pick one or the other.