Adam Zopf, the man who figured out a way to make every high school graduate in the world fear coming back to their ten year reunion, is back with a darker more personal tale.

Genre: Indie Dark Comedy

Premise: A young man who sees his dead girlfriend wherever he goes tries to start dating again.

About: Many of you remember writer Adam Zopf from his screenplay, Reunion, which I reviewed in 2011. I met with Adam recently and he passed me his latest screenplay, which I was surprised to learn wasn’t a horror film but a dark indie comedy. Dark indie comedies are tricky. You gotta have a unique voice and you gotta be careful not to get too depressing. Sideways is a good example of striking that perfect tone of darkness and hope. I was interested to see what I would get with Adam’s foray into the genre.

Writer: Adam Zopf

Details: 94 pages

After meeting with Adam, I was talking to my assistant and mentioned one of the scripts he had pitched me. She loved the idea and asked if I could send it to her. What do you like about the idea, I asked. It reminds me of one of my favorite movies, Lars And The Real Girl. This is, of course, exactly why I was scared to read it myself. I severely disliked Lars And The Real Girl. I just don’t spark to stuff that’s super depressing and ultra heavy-handed. I like to think of myself as a hopeful optimistic person, and you usually see that in the scripts that I like.

So my assistant got back to me less than a day later and told me she really liked Lily and that I needed to read it. Since she had basically hated the last 20 scripts I’d sent her, this meant something. And I was going to read the script at some point anyway. I know Adam’s a good writer. But it’s scary reading something from someone you like that you have a feeling you’re not going to like. As much as I dug Reunion, a script about a dead girl staring at our main character for 90 minutes sounded kind of…morbid. So as I flipped open the first page, I heard myself mumbling, “Please don’t be depressing please don’t be depressing please don’t be depressing…”

29 year-old writer Michael Dorsey is going about his daily routine. He’s grabbing breakfast. He’s working out. He’s writing. There’s one difference between Michael’s routine and everybody else’s though. Everywhere Michael goes, he sees his dead girlfriend, Lily, in the corner. Which sucks. Because it’s been nine entire months since she’s died. And that’s not fair. It’s so bad that he’s been ordered to get therapy about it (for what reason, I’m not sure).

Even outside of the Lily thing, Michael’s not a very happy dude. He hates his job as a telemarketer and is annoyed by just about everyone he runs into. Well, almost everyone. When Michael moves into a new place, he meets the handyman, the pint-sized Randy White Washington, who will tell anyone within shouting distance that he’s the main drug dealer in town. Big drug dealer or not, Randy’s a pretty cool dude.

As Randy and Michael become friends, Randy encourages Michael to get back out there. Start dating! Michael takes his advice and after a couple of false starts meets Anita, an aspiring British actress. The two hit it off and all of a sudden, Michael’s life is starting to find purpose again. Kick ass!

Well, that is until Dead Lily begins to realize that Michael likes this girl. This seems to launch her out of her cryogenic staring state and actually start COMMUNICATING with Michael. This fucks poor Michael up to no end, who’s now unsure whether to keep pushing for Anita or “go back” to Lily. As you can imagine, the situation becomes so intense that everything in Michael’s life starts crumbling apart again. Michael realizes that unless he does SOMETHING to get Lily out of his life for good, he’ll never live a normal life again.

One of the things I like about Adam is that he writes with this simple easy-to-read compact prose. Never is there a word in one of his scripts that shouldn’t be there. I could see a lot writers taking a script like this to 105 or 110 page territory. Adam knew exactly how much space he needed and didn’t write a single word more than that.

What I also liked was the IDEA behind closure here. I’m not going to spoil anything but the revealed backstory that explained why Michael hadn’t gotten over Lily, and the subsequent extremes he had to go to to find closure, while utterly ridiculous, made sense within the context of the script. I liked what Michael had to do to move on. That part was really cool.

However, my biggest fears going into the read were realized. And again, I believe this is more me than Adam. I’m just not into these really downer stories. I need hope. I need laughs. I need life. I always say the “woe-is-me’ character is the most dangerous character to write because nobody likes someone who feels sorry for themselves. Michael doesn’t quite seem sorry for himself, but he is a pretty miserable guy. He’s a downer. And I understand why. It’s motivated. Who’s not going to be down after losing their girlfriend? But I just personally have trouble latching onto and rooting for those characters.

I actually think Adam might’ve sensed this, might’ve known this could be a problem, and so he brought in the character of Randy. He’d be our comic relief. He’d be our “fun.” And he almost achieved that but, I don’t know – he wasn’t humorous enough in my opinion. He wasn’t Thomas Hayden Church in Sideways. He was more a ball of misguided energy. I would’ve liked to have seen more humor pulled from this character.

Another issue for me was the plot. These super light plots always leave me wanting more. There aren’t enough characters, enough twists, enough subplots. You gotta look somewhere to spice up the pages and i didn’t see that. I think I knew pretty early on what this was about, and most of the script just reinforced that. For example, I knew Lily was always going to be there. That aspect of the story didn’t change until page 80. PAGE 80! A lot more mystery could’ve been culled from that subplot. Or maybe you do a series of flashbacks throughout the script to their relationship so we can get to know Lily, so we can better understand why Michael was so obsessed with her. The only thing we know about Lily now is that she’s a creepy chick who stares at our hero. Ultimately, everything was played very straight forward with the story, so you always knew where the script was going before it did. And I’m a guy who likes to be kept off-balance.

This is why I get nervous whenever I’m sent a more personal piece from someone. I always get scared that it will be too “indie,” if that makes sense. And Lily In The Corner felt too indie to me. What does that mean for Adam’s script? Well, as I pointed out, I don’t think I’m the audience for this. My assistant was and she loved it. I think the real audience you’re trying to win over here are the people who loved Lars and The Real Girl. If they tell you that Lily kicked ass, you’re in good shape. So I guess I’ll turn it over to you guys. What’d you think?

Script link: Lily In The Corner

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: I’m usually wary of any script centered around a writer. I just feel that writers and their lives are boring. So it always feels to me like a lazy choice. If the writing is tightly integrated into the plot (i.e. Stranger Than Fiction) then it’s okay. But I didn’t see how Michael’s writing played into the plot at all. If the story focused more on how he hasn’t been able to write since Lily died, then it would make more sense. But I really didn’t see any particular reason why Michael needed to be a writer. Am I off base on that assertion? Adam? I’m sure you’ll have an opinion on this. ☺

Genre: Sci-Fi

Premise: Stranded on a strange planet, a group of marines must fight off an alien enemy while trying to discover the origin of giant artificially constructed halo orbiting the world.

About: Oh boy does this one have a backstory. The Halo movie was one of the surest things in Hollywood. This thing would’ve broken box office records everywhere. And with Peter Jackson taking point as the producer of the series, you might as well have started opening Halo Banks around the Jackson household that just spat out money. Jackson made a controversial choice to helm the the mega-movie, hiring little-known director (at the time), Neil Blomkamp, but that controversy subsided quickly when people saw his jaw-dropping sci-fi short films (one of which is included below). So as everyone eagerly awaited the next big Halo movie news, they were blindsided when the project was abruptly canceled. Why was it canceled? MONEY, of course. The studios are used to having a lot of leverage in these situations. But this time they were going up against a company bigger than they were, Microsoft. Microsoft just wasn’t going to give up all the profits the studios wanted. So they said, “Fuck you.” And that was that. The film was dead. Which is really too bad. It had a great producer, a great director, and a great writer (Alex Garland). All the pieces were in place. But I guess we’ll never get to see that place. What did we miss? Let’s find out.

Writer: Alex Garland

Details: 2/6/05 draft (127 pages)

I remember playing the first Halo game. It was like nothing I’d ever experienced before on the video game front. My favorite moment was weaving my way through a huge cave, coming out into a valley, and seeing this huge war going on in front of me, with each side lobbing missiles and grenades at each other – the kind of thing you were used to seeing in a cut-scene. I finally realized that it was my job to go INTO that battle. I was about to become a part of it. It all felt so seamless, so realistic, so organic. Video games just hadn’t done that before then. And on top of that, there was this really cool story going on the whole time about this “Halo” thing floating up in the sky. A big reason I kept charging through the levels was to find out more about that giant mysterious object. The combination of that seamless lifelike playability and the great story made Halo one of the best video games I’d ever played.

Naturally, like everyone else, I couldn’t wait for the sequel. And when it finally arrived, I was quietly devastated. Gone was the focus on story, replaced by a focus on multi-player. I’m not going to turn this into a debate about which is better. All I can say is what’s more important to me. Since you guys read this blog, you already know the answer to that. Story story story. I don’t remember anything about the Halo 2 story and checked out afterwards. I never even played Halo 3.

Which brings us to the Halo movie. It’s gotta be one of the most interesting video game adaptation challenges ever. The game itself is inherently cinematic, which should make it an easy base for a film. However, it’s also heavily influenced by past films, particularly Aliens, which essentially makes it a copy of a copy. How do you avoid, then, being derivative? Also, which story do you tell? Do you retell the story of the first game in cinema form? It’s got the best story in the series by far, but don’t you risk the “been there, done that,” reaction? Or do you try to come up with something completely new? And if you do come up with something new, how does that fit into the chronology of the other games? Oh, and how do you base an entire movie around a character who never takes off his mask? That’s going to be a challenge in itself.

I had all of these questions going on in my read in anticipation of reading Halo. Let’s see how they were answered…

The year is 2552. A species of nasty aliens known as The Covenant are waging an all-out war against the human race. A “holy” war they call it. “Holy” code for “turn every single human into red pulp.” In the midst of a large scale space battle, the largest of the human ships, the “Pillar of Autumn” is able to make a light speed jump out of the action.

They arrive outside a unique planet with an even unique(er) moon – A HALO (“You can be my Halo…halo halo!”). This artificial HALO moon thing is fascinating but before the humans can start snapping cell phone pictures of it, the Covenant zips out of lightspeed behind them and starts attacking their ship!

Captain Keyes senses that his ship is about to be shredded into a billion slivers of steel so he wakes up his secret weapon, and our hero, Master Chief. Master Chief is part of a supreme soldier project called the “Spartans” (apparently their creator was a Michigan State fan). He’s insanely tall, insanely strong, and is coated with some super-armor that could probably deflect a nuclear bomb.

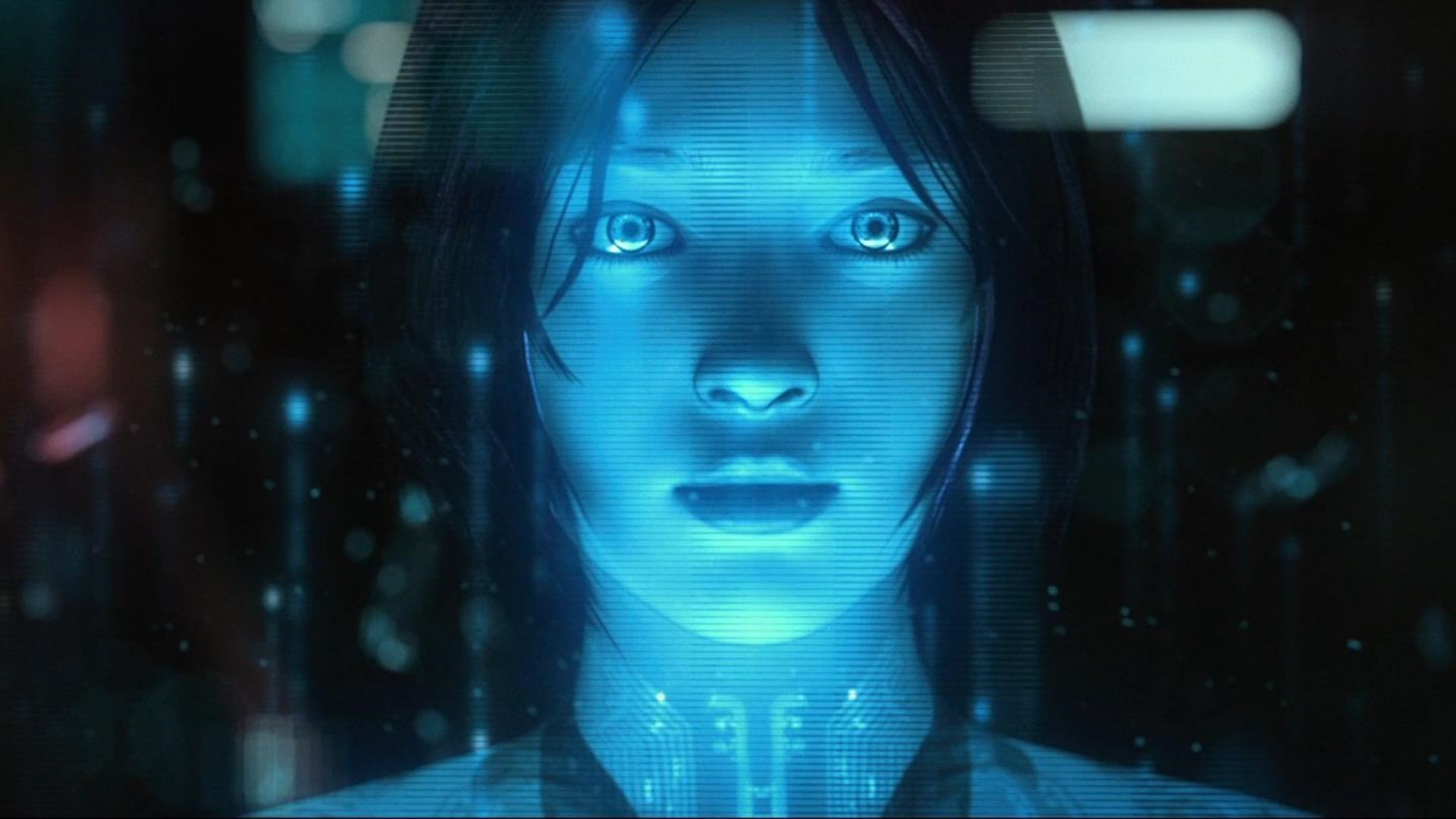

Keyes tells Master Chief he needs him to take the ship’s AI, a witty little female thingy named Cortana, to the safety of the planet below. If the Covenant catch her, they’ll have access to all sorts of revealing stuff, including the location of Earth, which would allow them to deliver their final blow to mankind.

Master Chief obliges because that’s his job, to oblige. So Cortana is wired into Master Chief’s suit and down they head to the planet for safety. Once there, they encounter a couple of problems. The first is that the Covenant are coming down to the planet to blow their asses out of the jungle. The second is that there seems to be some long-since-left-behind alien structures all over the planet, tech that belonged to a previous species much more advanced than both the humans and the Covenant. And this tech looks to have been created for nefarious purposes.

Somehow, they realize, this all ties back to Halo, and it’s looking like the only way they’re going to get out of here AND save the universe from these spooky ancient aliens, is to blow Halo up, something that isn’t going to be easy with the oblivious Covenant trying to kill them at every turn.

Uhhh, does this plot sound familiar to you? That’s because it is! It’s the exact same plot, beat for beat, as the video game. Sigh. Yup, Halo: The Movie was just a direct adaptation of Halo 1. I don’t know if I wasn’t into it because I always knew what was coming next or if the story didn’t translate well, but I often felt impatient and bored while reading Halo. Garland did a solid job visualizing the story for us. But I still felt empty afterwards.

A big part of that had to do with Master Chief. I was worried about him beforehand because in the video game, like a lot of video games, you don’t know much about your hero, mainly because the hero is you! You’re doing all the running around and the jumping and the shooting and the thinking, so regardless of whether the guy has any backstory or not, you feel a deep connection to him because you’re controlling him.

A movie is different though. We need to have some sympathy or empathy for the hero, and a good portion of this is built on your main character’s life, what’s happened to him before he’s reached this point. There’s a recurring dream sequence where Master Chief is on some battlefield and gets saved by a marine that’s SUPPOSED to make us feel something for him, but I’m still unclear as to what that was. His haunting backstory is that someone had to save him on a battlefield? Not exactly the stuff that wins writers Oscars.

But what really hurts Halo is how damn reactive Master Chief is. He doesn’t do anything unless someone tells him to do it. “You have to bring Cortana down to the planet.” “You have to go back up and save Captain Keyes.” “You have to go find the map that will lead us to the Halo Control Room.” Again, that kind of stuff works in a game because IT’S NEEDED. If there wasn’t someone telling us what to do, we wouldn’t know where to move our character. We wouldn’t have any direction.

But in movies (ESPECIALLY action movies), we need a character who’s active, who makes his own decisions. Or at least we usually do. There was this overwhelming sense of passivity in Halo, like we’re being pulled along on a track, at the mercy of a conductor announcing, “We will be arriving at the midpoint in twelve minutes. Midpoint in twellll-ve minutes.” Why can’t we be in the cockpit of a plane, making our decisions on where the hell we want to go?

And so the story quickly brought on this predictable quality to it. Every section was perfectly compartmentalized. Here’s mission 1. Here’s mission 2. Here’s mission 3. There was no freedom to the story like there was in, say, a Star Wars, where something unpredictable would happen every once in awhile (the planet they spent the first 45 minutes preparing to get to is gone upon their arrival!).

I DID like the idea of adding a MacGuffin here (Cortana) but unlike other movies with strong Macguffins (Star Wars – R2-D2, Raiders – The Ark, Pirates – the gold coin) I never really got the sense that the Covenant wanted Cortana that badly. If everybody isn’t desperately trying to get the MacGuffin, then there’s no point in having one.

But I think whichever incarnation the Halo movie takes (assuming it gets made), they need to focus a lot harder on the character of Master Chief. Really get into who he is and what he is and how he got here and how he’s going to overcome whatever issues he’s dealing with. That stuff matters in movies. There was a hint in the script of Master Chief being this genetic anomaly, a non-human. Why not explore that? This feeling of not fitting in? It’s one of the most identifiable feelings there is and has worked for numerous other sci-fi franchises (Star Trek, X-Men). Not that any of this will affect box office receipts, of course. But if they want to actually make a GOOD MOVIE, something that lives beyond opening weekend and brings new fans to the game itself, more attention to character ain’t going to hurt.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: I think there are three kinds of characters. There’s the active character, the reactive character, and the passive character. The active character is almost always best (i.e. Indiana Jones) since it’ll mean your hero is driving the story. The Reactive character is the second best option (i.e. Master Chief). “Reactive” essentially means your character waits for others to tell them to do something, and then the character does it. I don’t prefer this character type but at least he’s doing things. He’s still pursuing goals and pushing the story forward. The passive character is the worst option. The passive character is usually doing little to nothing. They don’t initiate anything. They don’t react to anything. They’re often letting the world pass them by. The most recent example I can think of for a passive character is probably Noah Baumbach’s “Greenberg” with Ben Stiller. Didn’t see it? Exactly, nobody did. Because who wants to watch a character sit around all day doing nothing?

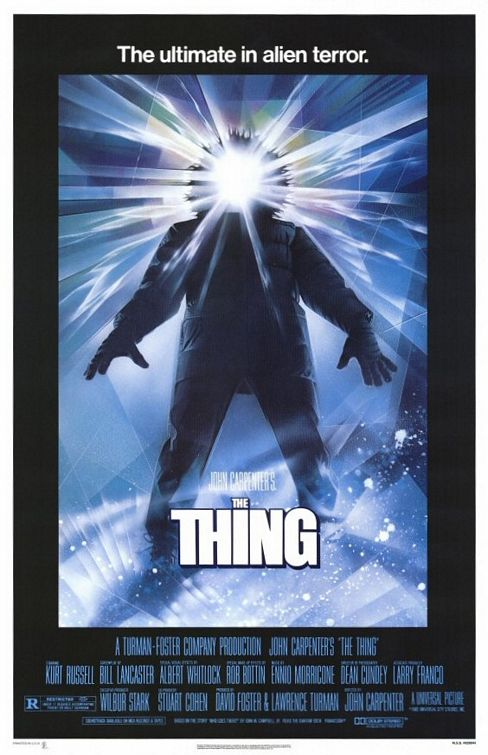

The Thing is probably one of the scariest movies ever made. People haven’t always seen it that way since it’s not set strictly in the horror genre. But man, I remember watching this film as a kid and being freaked the hell out. When the spider-legs grew out of that man’s decapitated head and began walking around? That image is still burned into my brain. The screenwriting situation behind “The Thing” is kinda interesting. Bill Lancaster, the writer, is Burt Lancaster’s son. His credits include only 2 other movies, “The Bad News Bears” (the original), and “The Bad News Bears Go To Japan.” He also wrote the Bad News Bears TV series. That was back in 1979. He didn’t write anything after that and died of a heart attack at the age of 49 in 1997. I’m baffled as to why Bill didn’t write anything else when he showed a clear mastery in two completely different genres. Was this his choice? Hollywood’s choice? Did the pressures of having a famous Hollywood father play into it? I’d love to know more. But since I don’t want to depress the hell out of all of you, I’m going to break down The Thing.

1) Use Clip-Writing to spice up action sequences – Clip-Writing is when you write in clips, highlighting primary visual queues. Clip-Writing can be very effective in action scenes as it helps the reader focus on the centerpieces of the battle, fight, or chase. We see it in The Thing when a Scandinavian crew has followed an infected dog into an American base.

CLOSE ON A .357 MAGNUM

As it efficiently breaks through a windowpane and into the cold. A steady hand grips it firmly.

THE SCANDINAVIAN

Getting closer. Kablam! Suddenly, his head jerks back. He falls to his knees and then face down into the snow.

NORRIS AND BENNINGS

Stare blankly, but relievedly at the fallen man. The dog whimpers in pain.

2) If Dialogue isn’t your strong suit, look to show more than tell – There’s actually some good news if you’re not a great dialogue writer. It means you’ll be forced to SHOW rather than TELL us things, which is really what you should be doing anyway. I noticed from reading and watching “The Thing” that a lot of the dialogue from the script was cut. Carpenter chose instead to focus on the visuals and the actions. For example, there was a scene early in the script where they’re walking to the helicopter and there’s a lot of explanation going on of what they’re doing. Carpenter cut a lot of that out, focusing instead on them simply getting in the helicopter and leaving. We know what’s going on. We don’t need a big long talky scene to explain it.

3) Only have your characters speak if they have something to say – This is an extension of the previous tip, and an important one. Your characters should be talking because they have something to say, not because you (the writer) have something to say. You might want to write a big monologue about how your character lost his sister or your opinion on the earth’s eroding ecosystem. That’s great. But would YOUR CHARACTER say that? I don’t think enough writers really ask that question. There’s nothing worse than reading a bunch of words coming out of a character’s mouth that you know are only there because the writer wanted to include them.

4) ALWAYS WORKS “There’s something else you should see” – I don’t care how bad of a movie or script it is, variations of this line ALWAYS work: “There’s something I need to show you.” You will have the audience in the palm of your hand until you show them what that character is referring to. With The Thing, that line brings us to a giant mutated gnarled mass of a body. If you can milk the time after the statement until the actual reveal, even better, as our anticipation will grow.

5) MID-POINT SHIFT ALERT – The Thing has a great midpoint shift. The first half of the script is about the discovery of this alien organism invading the base. Remember, a good midpoint shift ups the stakes. So the shift here is when they learn that any one of them could be the alien entity. It’s no coincidence that this is when The Thing really gets good. A great mid-point shift will do that.

6) Carefully plot how you reveal information – Always be aware of what order you reveal your information in and how that affects the reader. One omission or one addition can completely change the way the next 30 pages reads. For example, here, the movie starts with an alien ship crashing. This gives us, the audience, superior knowledge over the characters. We know they’re dealing with an alien. This means we’re waiting for them to catch up. Now imagine had Lancaster NOT included this opening shot. Then, everything that happens is just as much a mystery to us as it is the characters. I don’t want to rewrite a classic, but the opening act may have been a little more exciting had we not received the spaceship information. We’d be equal amounts as baffled and curious as the characters.

7) SHOW DON’T TELL ARLERT – In the script, the characters have about a page and a half dialogue scene talking about how if the alien makes it to civilization, it could destroy the entire world. It’s not a bad scene. But they replaced it in the movie with a simple shot – Blair staring grimly at a computer chart that states: If the organism reaches one of the other continents, the entire world population will be contaminated within 27,000 hours.

8) Foreplays not Climaxes (Aka Don’t reveal all your fun stuff right away) – I see this all the time with amateur writers. They’re so excited about the cool parts of their script that they can’t wait to write them! So when it’s time, they drop all their reveals on you simultaneously, like a giddy kid who’s been waiting to tell you about his trip to Six Flags all day. For example, the Americans find the Norwegian crew’s video tapes from their destroyed camp and start watching them to figure out what happened. An amateur writer might have slammed us with all the crazy reveals immediately (alien ship, alien body). But Lancaster takes his time with it, showing the Norwegians having fun on the tapes, basically being boring. It isn’t until a handful of scenes pass that we see the Norwegians blow up the ice and discover the alien ship. If you throw all your climaxes at us at once, we get bored. Give us some foreplays beforehand.

9) Lack of Trust = Great Drama! – Once characters stop trusting each other, the drama in your story is upped ten-fold. You now have characters who are guarded, suspicious, not saying what they mean, probing. This ESPECIALLY helps dialogue, since it’ll create a lot of subtext. Whether it’s because they think another person is secretly a shape-shifting alien or because they think their husband cheated on them with their best friend, it’s always good to look for situations where characters don’t trust one another.

10) Use Cost/Value Ratio to determine whether a scene is necessary – There was an entire cut sequence in The Thing where the dogs escaped the compound and MacReady went after them with a snowmobile. It was a nice scene but it wasn’t exactly necessary. Producers HATE cutting these sequences after they’ve been shot because it’s cost them millions of dollars. Which is why they try to cut them at the script stage. This is where you can benefit from pretending you’re a producer. Simply ask yourself, “Is the VALUE of this sequence worth the COST of what it would take to shoot?” But Carson, you say, why should I care about the budget? I’m not the director or producer. That’s not the point. The point is, you’ll start to see what is and isn’t necessary for your script. If you say, “Hmm, would I really pay 5 million bucks to shoot this chase scene that doesn’t even need to happen?” you’ll probably get rid of it, and your script will be tighter for it.

These are 10 tips from the movie “The Thing.” To get 500 more tips from movies as varied as “Aliens,” “When Harry Met Sally,” and “The Hangover,” check out my book, Scriptshadow Secrets, on Amazon!

Warning: This is a rare “flu-written” Scriptshadow entry. There are only a few of these in existence. Which means they’ll be worth a lot of money someday. Save yours in expensive laminated paper please. Thank you.

Genre: Cop/Found Footage

Premise: Two cops (and best friends) begin taping their daily exploits, which include numerous busts and adventures.

About: David Ayers (Training Day, The Fast And The Furious) wrote and directed this. It starred Jake Gyllenhaal and Michael Pena.

I did a script review over a year ago and kind of hated it, expecting it to be a huge box office dud. But the movie ended up doing okay (41 mil) and getting a lot of love from critics (85% on Rotten Tomatoes). Hmm, I thought, now I have to watch the movie and figure out how he saved that dreadful script. It was time for some Scriptsahdow script-to-screen analysis!

Writer: David Ayers

Details: Script was 97 pages

I had this grand idea of how I was going to tackle my End Of Watch script-to-screen review. There were going to be charts. There were going to be witnesses. There was going to be a celebrity guest and possibly a spin-off reality show. Something like Storage Wars.

But the thing with the flu is that it doesn’t allow you to think until you restrain it with a large bottle of Nyquil. I call this practice, “Quilling,” and it brings whatever you’re working on into Hubble-like focus. Behold. Beware. Be afraid. What I write below may not be used against me in a court of law.

When Larry David was pitching his “show about nothing” (Seinfeld) to a group of studio execs, the execs focused excessively on the dynamics of the friendships. “Well we need them to not like each other,” they said. “Why?” an annoyed Larry David asked. “Because you need conflict,” the execs said. “You need drama, and drama comes from conflict. If there’s no conflict within the group, then the conversations between everyone are going to be boring.” Furious that the execs were all hung up on this detail, Larry stared them down and said, “Why the hell would you be friends with someone you didn’t like?” The execs stammered about, looked at one another for an answer, but nobody had one. So Larry got his way. There’d be no “conflict” between his core group of characters.

I bring this up because conflict IS a necessary component of drama. We do need it in some capacity in order to make our stories interesting. However, there’s an antithesis to conflict that can actually be worse than having no conflict at all. MANUFACTURED CONFLICT. This is when the writer goes into a movie proclaiming “I’M GOING TO ADD CONFLICT!” Two cops who hate each other for no reason. Two romantic leads who hate each other for no reason. A mother and daughter who hate each other for no reason. No reason, that is, other than that the writer wants to ADD CONFLICT!

Is having no conflict better than that? Probably. But you’re picking between two worst-case-scenarios. Which leaves you severely limited in the storytelling department – the department of “actually keeping people entertained.” These two cops looooooved each other. They’d take a bullet for each other. They pat each other on the back whenever the other makes progress in his love life. They give each other man-hugs and nose-to-nose Whale Rider kisses.

True, you’ve stripped down all the artificial bullshit. There’s nobility in that. I mean in real life, a lot of partners probably love each other. So it’s real. Raw. True. I admire Ayers trying to get to the core of this. But when your Subway fresh take puts you at a dramatic disadvantage in the storytelling department, you better be able to pay up at the end of the line. Those five-dollar footlongs don’t include the meatball sub.

Which is a nice way of saying, “What else ya got here?” And End of Watch didn’t really have anything. I mean, the whole reason I wanted to do a script-to-screen breakdown of the project was that I hated the script and heard the movie was great. I was hoping to see a great movie so I could see what changes they made to save the film or just see how a strong directing vision can save a bad screenplay. I got neither.

In fact, I found the movie to be even more boring than the script. Let’s start with the plot. Oh yeah, there isn’t one. I think I understand the motivation behind this. We’re going for “real.” We’re staying away from common cop-movie tropes. If you add a plot, it all starts feeling manufactured, manipulative. There’s no story in real life because real life is random! Therefore we can add no plot!

Again, I applaud the fresh take. But you’ve already given me two cops who spend three-quarters of the movie telling each other they love each other. So there’s no conflict – and now – NO PLOT! I mean what’s next? Are you going to shoot this as a silent film? Are you going to shoot the whole thing in one take? I mean how many handicaps do you want to give yourself?

Lots of talking and laughing in this one. Lots.

Lots of talking and laughing in this one. Lots.

I’m DYING to figure out what people saw in this movie. Cause I missed the cruise ship. Is it cool because it felt “real?” I might be able to buy this argument but the acting was so fake-y. There wasn’t a moment in this movie where the actors weren’t doing the “faux-reality” thing. Those wacky off-screen moments we never see in cop films? Like the noogies cops give each other? We get those here! And they feel like they’re trying soooo hard to be spontaneous home video captured moments. It may be that found footage and famous actors aren’t meant for each other. I mean a big reason the found footage format works – and this dates back to Cloverfield – is that you’ve never seen the actors in it before. They were all new faces. So it really did feel like real people.

Speaking of found footage, I’m not sure Ayers ever decided if this was a found footage movie or not. It was found footage in the script (we’re told at the beginning of the script the footage was “found”), but in the movie, it was vague, something like, “These are the lives of two LA PD cops caught on camera.” It still starts, however (like the script), with Jake Gylenhall carrying a camera around the station, claiming he’s taking filmmaking as an elective at night school (one of the lamest motivations for found footage I’ve ever read – there was NOTHING about Jake’s character that made you think he’d be interested in filmmaking). The partners then add pin-cameras to their uniforms and now we have our basis for why this footage was captured.

Except a quarter of the way through the film, we start getting random third-party shots of the character. For example – Jake doing a work-out on the roof, shot from about 100 feet away. Was this another “real person” who just happened to be taping Jake working out and the police later happened upon this footage (Guy comes into police station: “Hey guys. You know that cop here who was in the papers? I taped him working out on the roof the other day! Wanna see the footage?” Errr, noo-oooo.

Look, it’s not a huge deal. I don’t want to present myself as (super nerdy voice) “Every shot must be motivated and make sense” Guy. But it speaks to a larger suspicion, which is that Ayers didn’t really know what he was doing here. He didn’t know what movie he wanted to make. By the third act, we’re seeing almost as many “third-party” shots as we are “found footage” shots. And it just seemed lazy. Like he stopped trying to figure out how to make it found footage, because he realized it would take too much effort.

(MAJOR SPOILER) There was also a major change from the script to the film. In the script, both characters die at the end. In the script, only Jake’s partner dies. Jake holds on and lives. This was about the only positive change I could find about the script to screen transformation. By leaving Jake alive, we have someone to grieve, someone to feel the loss. If they’re both dead, it’s kinda pointless. Neither of them know the other’s dead. Who cares? You needed one of them to grieve so we could grieve with them.

But that wasn’t enough to save this. I was rubbing my eyes 15 minutes in knowing that everything I’d read was pretty much kept intact. And it kept going and going and going. And not in that fun Energizer Hominid way. I need fans of this film to explain it to me. Why did you like this? What in the world was good about it? I was bored to tears!

[x] What the hell did I just watch?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the ticket

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Manufactured conflict is your evil enemy. Avoid it at all costs! Say you want to add conflict between two characters. There’s Joe, a Central Park birdwatcher, and Frank, his bird-watching pal of 30 years. Manufactured conflict would manifest itself like this for our hack writer: “These two hate each other just because.” You figure that will lead to all sorts of awesome dialogue because they hate each other! And hate is conflict and conflict is good say screenwriting teacher! No, it will feel false and we’ll see through it. Instead, dig into Joe and Frank’s relationship more. Maybe they’ve been friends for 30 years, but just recently Joe spotted a rare never-before-seen Flying Spotted Nested Canary at the park and he’s become a bit of a celebrity because of it. He’s had a few articles written about his discovery. He was given the “New York Bird Watcher Of The Month” award by the city as well. And guess what? It’s gone to his head a little. So now he speaks from a place of superiority (as opposed to equals) around Frank, inadvertently giving him tips on how to spot rare birds, and overall just becoming annoying. This has gotten to Frank, who’s holding his tongue every time the two get into a conversation, as he just wants to scream out at Joe to SHUT THE HELL UP! You see how this conflict emerged from a natural backstory between the two characters? Therefore it makes sense! As opposed to just being slapped on there. Big difference!

Quick note: I’m moving today’s Amateur Friday script review to next Friday. So if you haven’t read it already, then get to it. Also, let me know which movie release you want me to review for Monday.

For those who may have forgotten, I did an interview with Jim a little over a year ago and found the attention to detail he puts into his analysis to be quite awe-inspiring. I mean this guy will dig into a scene at the molecular level to figure out what’s wrong with it. I think of myself as more of a macro guy, looking at the big picture, which is why we tend to have some fun conversations whenever we chat. I’m kinda like, “Do you really need to look at it that closely?” And he’s like, “Yeah, you do!” Having said that, my most recent obsession has been scene writing, which is more of a micro thing. Jim is actually working on a scene writing book and he told me he spends 2-3 hours on just scene writing in his new DVD set (Complete Screenwriting: From A to Z to A-List) that comes out next month. Since I want to learn more about what makes a scene great, I thought I’d bring him in and have a discussion/debate.

For those who don’t know Jim well, he worked in development for Allison Anders’ producers, produced Hard Scrambled, which includes Black List writer Eyal Podell. He works as a story analyst for A-List filmmakers and recently directed a feature film The Last Girl, which he discovered in a contest he ran. Next month he’s coming out with the most comprehensive DVD screenwriting teaching set on the market. I’ve been bothering him for a copy as soon as it’s ready and am currently getting an express shipment from New Yawk as we speak!

SS: Okay Jim, good to talk to you again.

JM: Good to talk to you Carson. I thought our last interview rocked. We were able to introduce two terms into the screenwriting lexicon. Story density and…

SS: …faux masterpiece, of course. I even give you credit for those sometimes.

JM. You’re a giver. So I see you’ve shaken things up a bit at Scriptshadow.

SS: Maybe more they’ve been shaken for me. Now let’s cut to the chase. Here’s why I brought you in today. I need to better understand scene writing.

JM: As you know, I am currently finishing up the first screenwriting book that focuses solely on scene-writing for Linden Publishing and I can tell you that two years of being immersed in just scenes has been a great learning experience for me.

SS: Oh, I know all about living inside a book. I have a million questions about scene writing but let’s start with this one. Lots of screenwriters will tell you that each scene is like a movie. They’ll have a setup, a conflict, and a resolution. Which sounds nice and pretty but when I watch movies, I definitely don’t see that all the time.

JM: At the beginning of movies, scenes are more likely to be structured like this but later, after setups are in place, scenes tend to get shorter. Think about the two lobster scenes in Annie Hall. In the later one, Alvie runs around as the completely non-neurotic woman has no reaction. The scene has a middle and an end and, on its own, gets by. However, the earlier scene where he and Annie are having fun doing the same thing is actually essential setup for that later scene to work. With the earlier scene as setup, the later scene is funnier, contains more thematic ideas about how we carry baggage from old relationships into new ones and reveals insight into Alvie’s unconscious desire.

SS: Okay, maybe I’m jumping into this too quickly. I didn’t know you were going to bring up lobsters and I’m afraid of lobsters. So let’s start with a more straightforward question – What makes a great scene?

JM: Ironically, structure. There needs to be an organic build up to a great reversal or surprise. For me, all surprise comes from setup, which means a lot of effort and craft goes into making a reversal or surprise work. Instead of using the word “goal,” which I know you like, let me borrow a phrase that actors use: “What am I fighting for?” It’s essential to have a character who is fighting for something, and then you have to find obstacles to place in front of that fight that are meaningful and fun for the audience, if not for the character.

SS: Interesting. Okay. So here’s a bigger question then – because it’s the thing that really separates the pros from the amateurs in my eyes. How do you do this for 60 scenes in a row? How do you make sure all of your scenes are good and not just have two or three good scenes scattered about?

JM: Without buying my 300-page book or ten-hour DVD set?

SS: Come on. Give us some love.

JM: There is a simple answer and a complex answer and they are the same.

SS: Is there ever a straightforward answer with you, Jim?

JM: No, and I will come back to that. The challenge is to always use the information in the scene in the most effective way. Here’s a simple example…

A girlfriend walks into a room and sees her boyfriend with incriminating, I don’t know, photos. What happens next?

SS: Well if it were me I would run.

JM: I’m talking more from the girl’s perspective.

SS: God, I feel like I’m back in school. I don’t know. There’d be an argument?

JM: Exactly. It’s a dead end. But let’s take a step back and ask what else could happen. Here’s how we can use the same information differently to create a way more dynamic scene…

She walks in and sees that he’s hiding or concealing these potentially incriminating photos. Now she has a goal, something to fight for. She wants to learn what he’s hiding or verify that they are what she worries they are. You have mystery, intrigue, blocking (as she tries to get past him to the items), secrets and conflict that can get at the nature of the relationship (blame, suspicion, mistrust, etc.). Let’s say he’s hiding invitations to her surprise birthday party instead. Depending on what the audience knows, you have either dramatic irony or a surprise twist that acts as a comeuppance to the girlfriend for being mistrustful.

SS: Okay, I’m digging that. Dare I ask what the complex answer is?

JM: Again, the challenge is to use the information in the most effective way. But now we expand the definition of information to include character orchestration, character flaws, backstories, personalities, thematic motifs, meaning built-in to locations and everything else. We’ve sort of backed into a definition of drama: Arrange any and all creative resources you have – character, story, the world – for the maximum emotional impact. If you can’t do it at the scene level, you can’t do it at the structural level.

SS: So every screenwriting book ever written has been wrong for focusing on the big picture? Including the genius Scriptshadow Secrets?

JM: That book was sooo too macro for me.

SS: Nice.

JM: I never bash other books or story paradigms. My attitude is that my detailed focus can complement everything else. How does learning forty new scene-level craft elements hurt you as a screenwriter? For instance, on the DVD set, I talk about avoiding exposition and a list of 12 ways to do it.

SS: There are exactly 12 ways to avoid exposition?

JM: No, of course not. But, remember your joke above about me not giving straightforward answers. I rarely do because I am blessed or cursed with an ability to see all things from multiple perspectives. Here’s how it manifests itself in teaching. Twelve is an arbitrary number but each one is a different take on how to avoid exposition. My hope is that viewers grasp on to one of the angles and it resonates… leading them to their own solution and understanding. But, essentially, every item on that list is a variation of the overriding principle in action: Look for a way to organize the elements for maximum emotional impact. Approaching scenes with this in mind will essentially take care of the supposed “exposition scenes”.

SS: Whoa, that’s deep. I’m gonna need an example here, compadre.

JM: Sure. This example will show how ordering “the information” can eliminate boring exposition and how scenes won’t always need a self-contained setup, conflict, and resolution.

In My Best Friend’s Wedding, Julianne (Julia Roberts) wants to break up Michael (Dermott Mulroney) and Kimmy (Cameron Diaz). Julianne’s best friend George (Rupert Everett) gives her solid advice by simply saying, “Tell Michael the truth, that you love him.”

In the next scene, Julianne talks to Michael but here is an example of a scene where the set up comes from the previous scene. We expect her to tell him the truth, and she gets close to it, a contrast that creates a nice reversal when she tells Michael the lie that she and George are engaged! However, instead of us hearing this, an ellipsis (intentional omission) and shift in point-of-view make us watch it from afar from George’s perspective as he tries to decipher Michael and Julianne’s confusing body language (mystery, suspense).

Now (surprise) Michael darts straight toward George to congratulate him. The “telling” is less interesting than the consequences. The filmmakers decided that the way to get maximum impact from this “information” would be to watch George squirm as he processes and adjusts to the lie.

We have a reversal that comes from setup: TRUTH to LIE.

SS: Okay, I like that. A reversal. We set up a scene to make it seem like we’re going in one direction, then reverse it so it goes in a different direction. Kind of keeps the audience on their toes since it didn’t happen the way they thought it would.

JM: Yeah, this sort of “change” is at the root all of my discussion about story. However, there is one more thing we have to do before the sequence is over. And it involves a burrito with a lot of carbs.

SS: Please tell me this means your DVD set comes with a gift card to Taco Bell.

JM: Come on, Carson. You know I like the finer things in life. It’s called the Chipotle Method. And it describes how sequences work.

SS: Yes! Chipotle. I love Chipotle. Are you going to buy me Chipotle?

JM: I’m going to do you one better and show you how Chipotle can be applied to screenwriting. Just like when you’re ordering from the Chipotle menu, you never go backwards. When you’re done with the rice section, you advance to the meat section. When you’re done with the meat section, you advance to the salsa section.

It’s the same with sequences. In a moment, My Best Friend’s Wedding will advance to a new sequence that will be driven by the assumption and the consequences of the lie. Once we make that crisp (y nachos) turn, we can’t go back. However, the filmmakers decided that Michael and the audience wasn’t convinced yet, so we weren’t ready for the twist.

In the cab on the way to meet everyone, he challenges Julianne and George to get clarity. This isn’t just a Q&A. Michael’s confusion has dramatic resonance and importance. He is fighting for something. He’s thinking, why didn’t I know about this? He may even be suppressing a tinge of jealousy. Once Michael accepts the reality of the lie, so does the audience and we move on to the next sequence.

The next scene is at a church where Kimmy and her family are prepping for the wedding. Julianne, George, and Michael enter. Same question: What’s the best way through this moment? Where is the heart of the drama? Who is the most agitated right now? George. Because he has to live the stupid lie. There is a nice little craft touch (surprise and joke). Julianne whispers “underplay” to George who, of course, does the opposite and acts completely-over-the-top as a way to punish her.

Michael darts out of the frame. We know that the others must learn this information to complicate the story. However, I hope everyone knows the exposition rule about never having a character explain in full something the audience already knows.

SS: Ah yes, kill me now when I see that.

JM: Exactly. So can we believe that Michael “downloaded” the facts to her? Yes. Do we have to see it? No? Another craft choice: let it happen offscreen and play it out in the reactions, which are way more fun. A SCREAM interrupts George abusing Julianne and prepares us for a surprise: Kimmy excitedly runs toward them, with her justifiably extreme perspective (Julianne is eliminated as a threat) to congratulate them.

Whew.

SS: Sheesh. Remind me to never get married when my best friend is secretly in love with me.

JM: Yeah, and we’re talking about five minutes of screen time and there are dozens of micro-craft elements that service the principle: ellipses, off-screen action, a discovery or epiphany instead of preplanning, turning exposition into conflict, exploring the not-so-obvious heart of a moment, allowing setups in previous scenes to affect the pacing of subsequent scenes and shifting the point-of-view in a scene. And I haven’t even mentioned a dozen or so dialogue elements worth looking at.

SS: So by your reasoning, there’s no such thing as an “Exposition” scene. There’s just information and the challenge to make it dramatic?

JM: Sort of. It’s almost like a self-fulfilling prophecy to admit there is such a thing as an “exposition scene.”

SS: Okay, what about another type of scene I see a lot of writers struggle with. The set-piece scene. Everyone thinks you just make all this big craziness happen and we’ll be wowed.

JM: I do think that set-pieces are important.

SS: Can you explain what they are?

JM: You’re referring to the classical definition of it being a big spectacle-oriented moment, with a wide scope, challenging logistics from a production standpoint and includes as many of the resource of the story as possible. A big dance number in a musical or the train chase at the end of Mission Impossible. And those are set-pieces. I define them a bit differently to help writers figure out the set-piece for their story.

A set-piece scene is where you go for it. Ask yourself, given your premise, concept and genre, what is the best scene I can write? For instance, in The Nutty Professor, part of the concept is that one actor plays several roles. The famous “I’ll show you healthy” dinner scene where Eddie Murphy plays all but one of the characters is an organic set-piece.

This is one of the reasons the DVD spends almost an hour on exploitation of concept. Writing a set piece is like distilling your concept into its essence or finding the perfect manifestation for it. By thoroughly understanding and assessing their concept, writers can nail their scripts’ unique set-pieces,

SS: And what about the opposite? The quieter scenes. For example, Good Will Hunting has a bunch of what I’d call ‘anti-set-piece’ scenes.

JM: Actually, that’s where I disagree 100%. In fact, almost as much as a Tarantino film, Good Will Hunting relies on set pieces. For its concept, there are several set piece scenes: the first therapy scene with Will and Sean, the Harvard bar scene, maybe even the long joke/storytelling moments and the session when Sean and Will bond over both having been beaten as kids. Without those great scenes, Good Will Hunting is an after-school special: a damaged kid goes to therapy and learns to love himself.

SS: I guess what I mean is, what about the not-so-set-piece-y scenes – where you basically just have characters talking?

JM: Earlier, I mentioned that I co-opted the phrase “what am I fighting for?” from the language of actors. The reason is because sometimes the idea of “goal” doesn’t help us tell the entire story.

SS: I love goals.

JM: I know you do but let’s take a look at the Good Will Hunting scene where Chuckie tells Will that he wants to see him get out of town. If Chuckie were his career counselor and just giving him some solid advice, the scene would suck. And a goal like “to convince him to leave” is nowhere near as strong as what I sense Chuckie’s fighting for. For his friend’s soul.

Think about it like an actor and director. If the actor said, “I am having a hard time finding the importance here. What’s the big deal about me telling him this stuff?” If you have a good answer for yourself or the character, then the scene probably works. Here, you could say this to the actor: “You and he are best friends and have been doing the exact same things together for the last ten years. But you realize now that you are keeping him back. These things that have brought you comfort and have felt good are killing your best friend, making him throw his life away. He’s not going to change anything, so you have to even if it means you will never see him again.”

SS: “What is the character fighting for in the scene?” That’s an interesting way to think about it. And speaking of these “talky scenes,” how does dialogue factor into your scene building?

JM: Typically, I’ll talk about dialogue last. Writers need to be reminded about the visuals first. I start with structure of a scene (beats and reversals) and then blocking, locations, props, motifs and strategies to help externalize the internal. Then, finally, dialogue.

On the DVD set, I discuss several advanced topics in dialogue that help writers break the rules: long scenes, talky scenes, monologues, rhetoric (storytelling within the scene itself), subconscious and extended beats. I use examples from Frost/Nixon, The Edge, Good Will Hunting, Inglorious Basterds and, of course, True Romance.

SS: I typically tell amateur writers to avoid long dialogue scenes because the longer they are, the more unfocused and wandering they tend to be. But there are writers, like Tarantino and Sorkin, who do it well. How do those guys make their endless dialogue scenes work?

JM: A lot of it is the same principles that are used in short scenes. A longer scene might need a bigger twist. It comes down to the offspring of our last interview… story density. If you have a long, talky scene, you gotta make sure there’s enough to keep it going. Is the dialogue actually action like in the opening scene of The Social Network? Are the characters casually shooting the crap or are they verbally sparring? Whether you deal with structure before or after the first draft of a scene, you can look at the finished product and determine if there is enough going on. Let’s say you think you only have half as much “stuff”. Then it’s simple. Double the amount of stuff or cut out half the fluff.

That said, there is no denying that making a long and talky scene work is easier for a great writer. Tarantino, Mamet and Tony Gilroy have all of the skills that a burgeoning professional writer has but they also have more. I discuss dozens of craft elements from the True Romance interrogation scene. Part of the reason that scene works is because Walken and Hopper are such good storytellers. Some of it comes from the writing and directing, but the actors add to the dozens of subtle touches.

Hopper will say something intriguing that raises a question and then take a long pause to puff a cigarette before he finishes the thought. He is milking the moment for suspense but it comes from character. The beat is that he is trying to lure the Walken character in to listening to the story so that he might save himself from a lot of pain and his son from death. I could talk about that scene forever.

And you got me thinking, Carson… there isnt’ room to do it here, especially with a beast like the opening of the Social Network, but I will cover the topic of long scenes and spend some time on that scene in one of my upcoming Craft & Career newsletters. It’s free and people can sign up at the site.

SS: By the way, you need to tell me which newsletter service you use later. I’m lucky if mine gets to half the people on my list. But we need to start wrapping things up. Is there anything else about scene-writing you think we should know?

You know the attention we put on the reversal twist in the sequence from My Best Friend’s Wedding? Dirty little secret, that skill… to turn a dramatic situation sharply so the audience and characters (when applicable), FEEL 100% that there is a new and opposite situation, is the underlying craft to all of screenwriting. Most books look at it only at a story structure level – acts and sequences – but my book and DVD take a micro approach and look at it at the level of scenes (beats), dialogue and even action description. If you can absorb and embrace the craft in making a line of dialogue or piece of action description turn, you will see the growth ripple through all of your screenwriting.

SS: Whoa. That’s a pretty powerful statement. Okay, I just want to know a little more about your DVD set before we go. What sets this apart from all of the other screenwriting teaching materials out there?

Remember, I directed the first 40 DVDS in the old Screenwriting Expo Series. I know what’s out there. I cover topics in theme, exploitation of concept and scene writing that no one else is doing.

And, from a production values standpoint, we weren’t trying to do anything but a talking-heads presentation on those Expo DVDs. My new set contains more than an hour of motion graphics. They add a ton of clarity to the viewing experience. There are some cool animated script excerpts that accompany scene analysis as well. And there are graphs and images that illustrate difficult concepts like character orchestration in ways that have never been done before.

And the great thing is that if your readers want to order it on my site, they can get 40 dollars off! Just use the code “SHADOW” when you order. It’ll be good through the end of the month.

SS: It sounds like you’re pretty passionate about it.

JM: This has been a two-year project and, yes, the DVD set is measurably exhaustive: I have poured everything I know about screenwriting into it. But on a personal note, I am risk-taker at heart. I always look to Go Big or Go Home. I feel that this is my legacy as a teacher. I am really proud of it and I believe it will positively impact and inspire writers of all skill levels.

SS: All right, Jim. Thanks as always for stopping by.

JM: Carson, I live for stopping by Scriptshadow.

SS: That is such a lie but I don’t care because it makes me feel all gooey inside.

JM: I know. The gooeyiness was set up in the first act.

SS: Take care and good luck with the DVD set!

JM: Thanks. This was fun.

To learn more about Jim Mercurio, you can head to his site. If you want to take advantage of the DVD set discount, head over to this page and use the code “SHADOW” when you purchase. If you have any questions, you can send Jim an email. Also if you enjoyed this scene writing discussion, check out a sample of his $19.99 online scene writing class which includes excerpts from the first two lessons and an outtake from our interview.