Maybe the most unique screenplay of the year!

Genre: Thriller

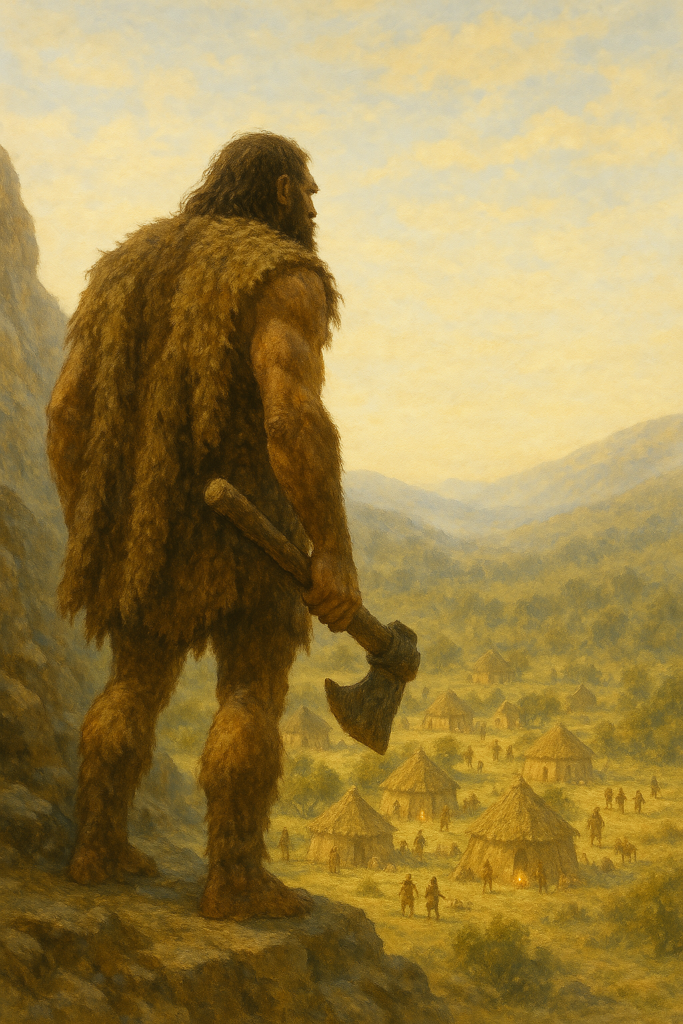

Premise: When his family is murdered and his child kidnapped, a Neanderthal goes on an epic rampage journey to save her from the new dominant species, homo sapiens.

About: This script made last year’s Black List. Donn Kennedy is a writer out of Milwaukee Wisconsin who has been writing for nearly 20 years.

Writer: Donn Kennedy

Details: 96 pages

I don’t think I’ve ever read a script where the writer has loved their script as much as this one. Donn Kennedy is having so much fun writing this that, at certain points, I thought he was experiencing some nirvana-like ascension to another plane.

Generally speaking, if the writer is having fun, the reader will have fun, too. However, you can overdo it. By only focusing on your own enjoyment, you can lose touch with the reader. So, which happened here? Let’s find out .

It’s 40,000 years ago.

It’s a time when you either kill or be killed. Society hasn’t really started yet. So, mostly, you’ve got these individual Neanderthal families scattered about, trying to get by. Our protagonist Neanderthal family is made up of the father, Bato, the mother, Kaza, and twin 13 year olds, Meeka (a girl) and Booka (a boy).

Bato is definitely a badass. He’s got a mysterious scar slashed across his face. The dude heads out every few days and kills a mammoth so his family can eat. His son, Booka, is a burgeoning artist, writing up stories on their cave wall. His daughter plays the bone flute and is pretty good at it. It’s your typical Suburban Neanderthal family from 40,000 years ago.

But, one day, when Bato is out hunting, a group of people come to his cave and murder his family. Well, they murder Kaza and Booka. Meeka was able to fight back and kill one. But the others still kidnapped her. When Bato arrives post-slaughter, he removes the mask of the bad guy to see… A SHOCKING FACE. Smaller nose. More distinct features. A homo sapien!

Bato immediately grabs his things and goes to find his daughter. But you have to remember, this isn’t some waltz through the local forest preserve. This is a land of endless predators. Bato finds that out immediately when he catches up to the group crossing a river in some kind of contraption (a boat).

Bato takes on Yama and kills him, then uses an alligator carcass to swim across the river and not get attacked by other alligators (it doesn’t work – the alligators attack him). Not long after that, he falls into a literal Venus flytrap. Like, one big enough to hold a Neanderthal. He uses fire to smoke his way out of that.

He eventually runs into a tribe of people who provide some much-needed first aid, only to then tie him up and march him out to some pole. Turns out they’re cannibals and they’re going to eat him! He cuts the rope and takes out 20 cannibals in a chaotic running dance through a bunch of hot-spewing geysers.

But the further he travels, the more distance the homo sapiens seem to create. Soon, he’s lost, turned around, and after two long years of pursuing his daughter, he’s shocked to find that he’s done a giant circle and ended up right back at his cave house. Hey, GPS was still in its infancy 40k years ago. Give him a break.

When Bato discovers another group of homo sapiens nearby, he fights them off. But when he’s about to kill one, he pulls off her mask and discovers that it’s… HIS DAUGHTER! But they don’t have time to reunite because Kaza, the leader who kidnapped her two years ago, is closing in. They must split up and Bato loses his daughter AGAIN! But he eventually discvoers where the homo sapien village is. So he arms himself and goes in for the final battle!

One of the things I crave most as a reader is SOMETHING NEW. I want to experience something I haven’t experienced before. The more unique moments you can pack into your screenplay, the better.

This script achieves that. It’s not like any script I’ve read in a long time. Bato is always running into something shocking – shocking for him, shocking for me. For example, he falls into this cavernous valley at one point and the next thing he knows, he’s face to face with a Homo Habilis. Just like the Homo sapiens wiped out the Neanderthals, the Neanderthals wiped out the Home Habilis.

Except there are a few still around. And this one is 7 feet tall and has the anger of his entire race ready to throw at Bato. It’s moments like that that made this script stand out.

Another thing that Kennedy did well is he made the writing sparse. Most paragraphs are one line long. He uses a lot of GIANT FONTS to emphasize the intensity of the moment. And what this does is it makes sure our eyes fly down the page.

Why is this important? Because there’s no dialogue. And I have seen many a non-dialogue screenplay die a quick death because they take forever to read through. Remember, dialogue takes 1/4 the time to read as a description. So readers love dialogue. Cause it allows them to shoot through a lot pages quickly. When you take all that dialogue out, a 100 page script can read like a 300 page script.

So it’s good that Kennedy understood that and created a writing approach that still allowed the script to read fast.

On the flip side, the writing here is borderline annoying. Every line is so on-the-nose that it’s hard not to roll your eyes at times.

And if you’re a reader who doesn’t like when the writer talks dirctly to you? You’re not going to like this script. Kennedy loves to tell you how he just made cutting the trailer easier, how much you’re going to love a scene cause it’s just like “Oldboy,” he even celebrates, on the page, pulling off successful setups and payoffs. There’s a ton of that here.

When it comes to flashy writing like this, I’m not going to say don’t do it because, the truth is, people either love it or hate it. And maybe it’s worth losing the haters if you gain the lovers in the process. The opposite of this is an entirely neutral style and that can be so boring that nobody likes it. So it’s a creative choice. Just know that you’re going to piss some readers off and they’re going to let you know about it.

As for the story, I thought the worst choice was the cut to two years later. I hate any big time cuts in a story because they tank all the tension you’ve built up. I mean, imagine if, at the beginning of last night’s White Lotus episode, there was a title card that said, “3 weeks later.” And the whole episode took place at the island 3 weeks later. Everybody watching would be like, what the f&%$?

I know why the writer did it. He did it to create the moment where Bato unknowingly fights Meeka. He did this because he’s a giant fan of Oldboy. I only know this because he says so earlier in the script. So, the big twist in that movie obviously motivated this plot development here, and this is something I always warn writers about. You want to be inspired by your favorite movies. But you don’t want them to impede upon your scripts too much.

There’s a huge reason why that twist was needed in Oldboy. There was no reason to cut to 2 years later here. The script would’ve been better had we kept the tension throughout, never leaving this timeline. The only reason that mistake was made was that the writer was obsessed with another movie. Make creative choices only to create the best version of YOUR MOVIE.

Overall, I don’t know how to rate this script. It’s got some great stuff. It’s got some terrible stuff. I do think the pitch of “Taken 40,000 years ago” is a good one. And the script is very visual. You can see, with a good director, this looking like a really cool movie.

So, for that reason, I think it’s ‘worth the read.’ And let me be clear about that so you understand. As a script, I would probably give this a “wasn’t for me.” But when you take into account how unique the concept is combined with how visual the movie would be, that’s what makes it read-worthy because the endgame here isn’t putting words on a page. It’s getting movies made. We should all be writing scripts that, like this one, have a shot at becoming a movie.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: You have to give the reader room to interpret what you’ve written. If you don’t, you risk being on the nose. Here’s a segment of the scene after Bato finds his family.

She’s alive! But mortally wounded

Falls by her, Bato cradles her head

His love. His world. The only thing good in this god forsaken prison of existence.

There is no reason for this third paragraph. None at all. You have to trust that the reader understands the gravity of this moment. You don’t have to yell it in his ear.

What I learned 2: This is the stuff that AI is great at. If you have a story idea like this, feed it into your favorite AI client and ask it, “What are 50 unique things my character might encounter on this journey, stuff that the average person woud never think of today?” And it will. It will give you at least 25 things you hadn’t thought of. And you can then build a lot of your plot beats or set pieces around the best of those things.

I was just going to make this a White Lotus post but I can’t ignore a record-setting weekend at the box office when we don’t get many of those anymore. Minecraft made 160 million dollars over the weekend, making it the biggest video game adaptation opening ever. That’s impressive.

So why did it happen? Here’s my theory. For the longest time, video game adaptations, like Doom and Assassin’s Creed, were competing for time from an audience who, historically, prioritized MOVIES over VIDEO GAMES. So, they always liked movies that were MOVIES.

But Minecraft is coming out at a time when the first generation that grew up priortizing VIDEO GAMES over MOVIES is now going to the movies. You can see that in the audience makeup. These are all kids at the showings. Kids who would rather play Minecraft than watch Star Wars. That generation is going to be a lot more open to video game adaptations.

So, I think what you’re going to see is a lot more video game adaptations and they’re going to do a lot better than video game adaptations of the past. Movies, meanwhile, are going to have to figure out how to compete with this. The simple answer is write better scripts and make better movies. But people don’t have a lot of confidence in that formula these days.

By the way, random fact I found out. The Minecraft movie was put together by the old Napolean Dynamite team. These guys actually have a unique voice. They’re not your average studio directing team. That probably had a big influence on the movie’s success as well.

Okay, onto the big show.

What we’ve all been waiting for.

The 90-minute White Lotus finale. Was it everything I was hoping for and a thousand things more?

Cause this show really rallied in the Scriptshadow household. After that silly snake-show episode, I was worried big time about the season. But it built its story back brick by brick and clawed its way up to the quality of the first two seasons.

Still, it needed to land the plane.

Did it?

Let’s just say this. Word was that the finale was bonkers. That was 100% verified tonight. IT. WAS. BONKERS.

****SPOILERRRRSSSSS****

There were some whopper climaxes here, none whoppier than what will forever be known as the White Lotus Empire Strikes Back moment. We’ll get back to that.

But let’s start with how Mike White subverted his climaxes. He gave you what you thought were climaxes. Then, right when you were about to wrap your arms around them, he pulled them back and gave you the real climax.

There was the secret family suicide pact that only Father Ratfliff knew about. White made us think that the whole family was going down. Then, at the last second, the dad changed his mind. The family was spared. Or so we thought. We are then horrified to see Lochlan fix a smoothie the next day, realizing that he’s going to ingest the last of the poison and die.

Another great climax subversion occurs with Rick Hatchett. We thought we finally got the conclusion to his life-long search for his father’s murderer last episode, only to learn, this episode, from resort owner Jim Hollinger, that the angelic portrait that Rick’s mom painted of his father was a complete lie and that his father was a terrible person. This reignites Rick’s desire to kill Jim, and a second storyline climax is on.

The reason these climaxes were so impressive is because the majority of screenwriters give you the climax you expect. There are tiny surprises along the way but we pretty much know what’s going to happen. Mike White faking a pass to us before he goes in for the dunk is what separates him from everyone else.

I can’t emphasize enough that Mike White does not have anything to work with here besides characters. He doesn’t have superheroes. He doesn’t have superpowers. He doesn’t have magic, or giant lizards, or the Force, or time-travel, or any of the things that other writers have access to to mesmerize audiences.

He just has characters and he’s so good at utilizing those characters in dramatic ways that nearly every scenario he creates is compelling.

If Mike White did have a superpower, I’d say it was setups and payoffs. I mean who would’ve thought that Saxon annoyingly ordering a blender from Amazon in the first episode so that he could meet his protein quota on vacation, would turn out to have such a giant influence on the finale? That’s what good setting up and paying off does.

And hey, did anyone read that article I posted on Friday? The one about how much bang for your buck you can get using ANTICIPATION as a screenwriting tool? I think Mike White might have. Cause the first half of this episode was driven by a succelent anticipation narrative – that the dad was planning to kill his family.

Once we see Timothy learn about the poisonous fruit growing nearby and we see him put two and two together with that blender, we know it’s going to be lights out for this family soon. And the great thing about this particular use of anticipation is that when you make it this powerful – as I said in the article, ramp up the stakes as much as you can for maximum impact – it not only drives THAT storyline, it drives the surrounding storylines as well.

Every time we cut to a different set of characters, we have this excitement/dread brewing in the back of our minds regarding what’s going to happen to the Ratliff family.

But there’s one scene that really represents Mike White’s talents as a screenwriter. And it’s not the best scene in the episode. It’s not even in the top 8 scenes. But it shows that you can do some powerful things with just three people and dialogue.

The scene occurs early in the episode, when Daddy Ratliff (Timothy), Mommy Ratliff (Victoria), and their daughter, Piper, are having breakfast after Piper has spent a “test” night at the monastery she’s hoping her parents will let her attend next year.

In fact, this is the whole reason the Ratliffs are here in Thailand. Piper tricked them, saying she was going to do an interview with the head monk, then revealed her bait and switch once they were there – She wants to live here for a whole year next year.

When Victoria learns this, she is mortified. Victoria is the typical Beverly Hills trophy wife who has grown dependent on the finer things. To think of her daughter stuck in this bare-bones smelly sweatshop of a monastery for a year is her worst nightmare. She wants Piper going to college, then going to grad school, then marrying a rich man, and living the same life she lives.

So Victoria allowed Piper to spend one night at the monastery hoping it would rattle her and make her want to stay in the U.S. So Piper spends the night there. It is indeed dirty and sparse and the food sucks and there’s no air-conditioning. And the scene in question happens the next morning at breakfast between Piper, Timothy and Victoria.

In the scene, Piper breaks down in tears, coming to terms with the fact that she is dependent on the finer things in life. That she isn’t capable of slumming it. And she hates herself for it but it’s also something she realizes is her truth.

Meanwhile, Victoria is absolutely ecstatic. It takes everything within her power not to stand up and start dancing. She’s so happy that her daughter is seeing the light.

Cut over to Timothy and he’s going through a completely different experience. By hearing that, like his wife, his daughter cannot live a life without the finer things, that means that he’s going to have to kill her in his suicide plan as well.

For those who haven’t watched the show, Timothy learned at the beginning of the vacation that his entire empire back in the U.S. is crumbling and that when he gets back, he’ll be sent to prison and lose every penny he has. Knowing that his family members cannot live that life, he is sparing them by taking them with him when he kills himself.

The power of this scene is that three characters are having three very different experiences despite all of them being at the same table discussing the same thing. One is crushed that she’s not who she thought she was. Another is ecstatic that her daughter isn’t going to ruin her life. And the third is devastated to learn that he now must include killing his daughter along with his wife and son.

Most of the three-person dialogue scenes I read in scripts are on-the-nose. There is no depth to the conversation. Characters are not experiencing different things. It’s all very straight-forward.

But here, White stragetically uses setups within his storylines so that he can create these rich multi-layered dialogue scenes.

So, I’m sure you’re all wondering, “What do I think about the “He is your father” moment? I think Mike White went too far. He obviously knew that if Scot Glen said the line (“I am your father”) he’d be crucified, so he wisely moved the line over to the wife. But I’m just not sure it works.

The success of these revelations depends on the audience having a certain amount of information. We had the perfect amount of information and not a line more for Darth Vader’s revelation in The Empire Strikes Back. But here, I feel like we were a good paragraph or two short of the amount of information we needed for this reveal to work. I just didn’t know enough about Rick’s father to care that this other guy ended up being his father.

This is actually one of the downsides of having such a successful show. You can’t test moments like this out like you could before. And I suspect that White wanting to keep this moment a surprise prevented him from seeking feedback and being able to gorge the reveal with the fuel it needed to shine.

But it didn’t bother me. The episode was jam-packed with excitement. It was never boring. If I had to rank them, I would say that this is the best final episode of the series. Season 1 was incredibly strong. But the sheer magnitude of everything going on here gave it the edge.

Another giant win for Mike White. This show has become my Super Bowl of Screenwriting Celebration and, therefore, I’m really depressed that it’s over. Is it confirmed that he’s making a Season 4? I know it’s assumed. But is it CONFIRMED?? Do we have linked quotes somewhere of Mike White saying, “Yes, I’m doing a 4th season?” God, I hope so. A world without The White Lotus is a much emptier world!

[ ] What the hell did I just watch?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the stream

[xx] impressive

[ ] genius

I’ve been thinking a lot about Scene Showdown and why it didn’t yield better results. I’ve gone on record here saying that you can’t write a good script if you can’t write a good scene. A scene is a mini-screenplay. So you need to be able to make at least those 5 pages entertaining if you have any hope of making 100 pages entertaining.

But how do I teach you that without working with you one-on-one (by the way, if you want me to help you in a one-on-one capacity, I consult on loglines, scenes, acts, screenplays, pilots, treatments, outlines, anything. Just e-mail me at carsonreeves1@gmail.com and we’ll set something up). The best I can do is explain by example. And two great examples I want to use today are Grendl’s scene from Undertow, which won the Scene Showdown, and last night’s episode of the Apple TV series, “The Studio.”

It all comes back to the concept of dramatizing. Dramatizing is using tools to generate DRAMA within the scene so that it’s entertaining and makes you want to turn the pages. Most aspiring writers do not dramatize. Instead, they approach scenes as information that needs to be conveyed to the reader.

For example, if a high school kid is picking up his date for prom, the aspiring writer will write a scene where the kid shows up, there’s a little nervousness between the couple, the parents take pictures, maybe embarrass the kids. The writer throws in a couple of jokes, thinking that’ll be enough entertainment to do the job.

No.

That’s not dramatizing the scene.

Dramatizing the scene is sending the nervous kid into the bathroom and when he thinks he’s been caught looking at his naked date through the window, absentmindedly rips his zipper up, accidentally getting his penis caught in the zipper. Now he’s got to figure out a way to get his penis out of the zipper without his dream date finding out. And everything gets worse from there.

Now you’re dramatizing the scene!

One of the best tools to dramatize a scene is anticipation. And both Grendl’s scene and the “The Studio” episode from last night use it effectively. With anticipation, you imply a negative possibility is forthcoming then cast doubt on what will unfold.

When you do this, it’s almost impossible for the reader not to want to keep reading. In Grendl’s scene, the negative possibility is not getting to the doctor’s apartment. This is a scary deserted apartment building at night. A young woman is walking around alone. That’s dangerous. Then you add this creepy guy in the elevator, which creates even more uncertainty about what’s going to happen next.

All of this creates ANTICIPATION. We’re eager to find out if she’ll make it to her destination alive or not.

Now, some of you may say, “But Carson. It’s just a basic scene where a woman is walking up somewhere at night. Anybody could write that.” That’s where you’re wrong. I know this because I read screenplays all week long where writers don’t dramatize scenes at all. And I know exactly how they’d write this scene.

They would have the woman show up during the day. The neighborhood surrounding this building is bustling. Families are enjoying a day out. Everything feels fun and safe. The woman calls up to the doctor. He’s a little annoyed that she came to his building (the extent of the drama in the scene) but he lets her up. The inside of the building is bright and inviting. There is no man in the elevator. And she gets to our doctor’s apartment without a hitch.

Do you see the difference? In the daytime version, there is no anticipation at all. These are the choices that every writer has at their disposal. They can choose to dramatize the scene, making each moment within the scene entertaining, or they can lay out a safe and inviting scenario with little conflict that merely gets our character from point A to point B.

Now let’s look at last night’s episode of The Studio for an even stronger example. It’s a stupendous episode of television and it does something that supercharges the anticipation. IT MAKES THE MOMENT MATTER. Which is another way of saying, it UPS THE STAKES. When you up the stakes, you up the anticipation as well.

If you haven’t seen the episode, titled, “The Note,” it follows our new studio head, Matt, and his trusted group of helpers (his top producer, Sal, his marketing genius, Maya, and his assistant, Quinn) after they’ve just screened a movie that Ron Howard made for the studio.

The group is ECSTATIC while watching the movie, believing it’s Oscar-bound. They get to the climax, which delivers in spades. Everyone is celebrating. This is going to be a mega-hit for the studio. And then… the movie keeps going. The story shifts to a motel where the main character (played by Anthonie Mackie) meets up with his dead son, who seems to be living as a ghost at the motel. And the two share numerous deep conversations set to melancholy montages over the next 45 minutes.

The group is gobsmacked. It’s the worst 45 minutes of film any of them have ever seen. Lucky for them, Ron is coming in for a meeting that day, giving Matt an opportunity to give Ron the note – cut the motel sequence. The problem is that the motel sequence is rumored to be Ron’s favorite sequence. And Matt is terrified of telling such an iconic director that the last 45 minutes of his movie sucks.

The episode takes place over the next 30 minutes, as Matt and his group try and figure out a way to give Ron the note.

What I love about this episode is that the plot is soooooo simple. There’s one tiny goal driving the story – Give Ron Howard the note. That’s it! That’s the whole plot right there.

And what is the main tool being used to keep us watching? That’s right: ANTICIPATION. We keep ‘turning the pages’ because we’re anticipating what happens when they give this note to Ron Howard.

But here’s where some advanced screenwriting comes in. Goldberg and Rogen, who wrote the episode, understand that they can ramp up the anticipation by raising the stakes. So they use every little opportunity to make the “note” more difficult to give.

For example, Matt is trying to establish himself as the most ‘creator-friendly’ studio head in town so that they can get the best directors to make movies for them. If he tells Ron to cut this sequence, word will get out that he’s a soulless corporate suit just like every other studio head, which is Matt’s biggest nightmare.

Also, while Ron Howard is publicly known as the nicest guy in Hollywood, Matt’s heard that he’s actually, secretly, a raging psychopath who burns to the ground anyone who crosses him. So there’s that to worry about.

But the biggest reveal is discovered after Matt does some digging about the sequence. It turns out that Ron Howard lost a very close cousin when he was a child. It’s something he’s been holding onto his whole life. He created this whole motel sequence as a way to finally, cathartically, move on from his cousin. This, of course, means that telling Ron to cut this sequence is telling him to cut the very reason he made the movie.

Note how, by upping the stakes, our anticipation of Matt giving Ron the note grows. It grows and grows and grows with each new reveal. That’s how you dramatize. That’s how you make people turn the pages.

Anticipation is such an easy way to dramatize scenes that you should be using it consistently in your writing. And, as you can see, the impetus behind the anticipation can be basic, as long as you up the stakes. You could build a scene around something as simple as going to the dentist. If your hero is terrified of the dentist. If this dentist is a glorified sadist. If your hero has a particularly gnarly procedure that needs to be done. All of that juices up the anticipation.

Anticipation may not be the answer to ALL of your screenwriting woes. But it’s a dependable tool you can call on whenever you need to ensure that your pages remain entertaining.

Enter the Slaughterhouse

Welcome to the new Slaughterhouse Review feature on Scriptshadow. I don’t know if this will become a recurring thing or not. I can’t imagine many screenwriters would want to be a part of it. The idea is that I give a review where I don’t hold back in the hopes that the writer truly understands where their writing needs to improve. We’re going to start this feature off with a review of a scene submission for Scene Showdown. This is one of the scenes that DIDN’T make the cut. Let’s find out why.

Title: Ghosted

Genre: Comedy Series

Writer: Brandon Crist

Setup: This is the opening scene of the pilot.

I read this scene four times. Once as a submission last week, then three more times before this review. On the second read, I re-acquainted myself with the material. On the third read, I tried to understand several aspects of the scene that confused me. And on the fourth read, I tried to identify the overarching reason the scene didn’t work for me.

It took me a while to figure it out. But then I realized that one simple adjustment would’ve vastly improved the scene. I will share that with you at the end of this review. But first, it’s time for some slaughterhousing. If you’re sensitive to violence, look away now.

I knew I wasn’t going to like this scene within the first few paragraphs. You get a feeling for these things when you’re reading. And I could just tell this wasn’t going to be my jam.

When it comes to comedy, the writing should be VERY DIFFERENT from every other genre. All readers care about is laughing. So you want to keep the writing EXTREMELY sparse. Unless something is critical to the comedy, don’t tell us about it.

“The lamp on the messy desk illuminates a pink rhinestoned skull.” Why do I need to know this? How is this going to make things funnier? I would go so far as to tell comedy writers never to write a paragraph over 2 lines long.

Next, we have the “Sexyback” ringtone. Look, it well may be the case that the character of Morgan is of the age that, when she was younger, “Sexyback” was a hit, and she’s always loved it, and that’s why it’s her ringtone.

But in the absence of any other information, it feels like a dated choice. I’m no spring chicken myself but I know that referencing Sabrina Carpenter, Chappel Roan, or Post Malone is going to make the writing feel a lot more current.

Moving on to the emergence of the blue hand. The second I read this, I deflated. My thought was: “Here we go again. Another dead person waking up as a ghost.”

Sometimes I don’t think writers TRULY COMPREHEND how many other people are writing scripts. If you’re not original, you are writing the same sorts of things as everyone else. I read a million scripts where someone wakes up as a ghost realizing they’re dead. And it’s always the same. They’re confused. They’re trying to find their bearings. It’s all very obvious.

That’s not to say you can’t write someone waking up dead. But you have to find a fresh way to do it! If you just give us the bargain bin version of waking up as a ghost, it’s going to put people to sleep.

We then get the Aidy Bryant casting suggestion. I think Aidy’s great but she’s not exactly a household name. I don’t think that most people will have heard of her.

Don’t use words like “ensemble.” I didn’t understand what that meant the first time I read this. Just say her clothes! Don’t confuse us! This is a comedy! We should never ever ever ever ever ever EVER be confused when reading a comedy script. If the reader is even confused ONCE when reading a comedy script, that comedy script is a failure. Because you should be making things INSANELY EASY to understand. I’m talking write like a 3rd grader.

The cleavage bounce joke doesn’t work because she’s just seen that her body is translucent and blue. I don’t see someone congratulating their cleavage in that moment. I suppose the argument could be “that’s the joke.” She’s a ghost and yet she still loves her tits. But I didn’t find it funny.

We eventually get to the bedroom where we get this paragraph: “The glowing lamp catches Morgan’s attention. With a morbid curiosity, she approaches to read what’s scrawled on a sheet of looseleaf.” And then her reaction: “Pills and poetry. How charming. His loss. His loss.”

This is a small thing but this needed one more beat in order to be 100% clear. Tell us that there’s a poem written on the pages! Don’t say, “she looks at what’s written” and then hear her say “Pills and poetry.” It wasn’t automatically clear that she’d written a poem. In fact, I wasn’t clear on the poem until she talked about writing it later in the scene. Just quickly describe that there’s a poem written on the page!

Same deal with her dead body. You write: “On the floor, her feet. Her real feet. Her body. She sees it lying there still, dead. She turns away. She pulls a strand of hair behind her ear, not really knowing where to look.” I didn’t know, initially, that she saw her dead body. You say, “On the floor, her feet. Her real feet.” I thought you were referring to her checking out her full ghost body for the first time. Just be clear!

Writers forget how much information the reader has to pull in when they first read a screenplay. Every moment is new information to them. This process of ingesting information taxes the brain. So it’s common, if something’s even mildly vague, for the reader to miss it. Whereas, later in the script, when we know all the characters and have a good sense of the plot, we’re better equipped to handle the nuanced moments. So, early on, be clear about things. Especially in a comedy where it doesn’t matter as much if you’re on the nose. So don’t back into a sentence about her dead body. Tell us it is her dead body! “She looks down and sees her dead body.”

Next we have Cynthia Erivo coming in. I don’t like this actress at all. I’ve hated her ever since she ruined The Outsider. So I was immediately put off by the casting suggestion. It’s the gamble you take when you suggest actors for roles. As you can see here, I like Aidy Bryant but don’t like Cynthia Erivo. Yet I only needed to dislike one to turn on the material.

Then she says this line, “One sec, babes! Gotta piss like Seabiscuit.” And that’s when I was done with the scene. I kept reading but I knew, after that line, that there was literally nothing this scene could do to win me back. I just think back to that time in 2012-2015 where, for whatever reason, probably because “Girls” was a big show, that every other ‘strong woman’ scene had a woman urinating in a bathroom while on the phone talking to another character. I don’t want to see that. I could show a guy taking a shit while on the phone in every other scene if I wanted to but that doesn’t mean that I should.

“She holds up her manicured finger. Her bracelets jingle as she waves her hand, processing what’s happening before her.” I have no idea what this paragraph is highligthing. She’s holding up a finger? Why? She’s waving her hand. Why? I don’t understand the gestures at all.

We then go to the bathroom where, despite the fact that her friend is a ghost, Charli continues to talk to her. I suppose this is the joke? The friend is acting in the opposite manner of how one would act when seeing that their friend is a ghost. But I’m not laughing because it’s hard to gauge the comedy tone here. I don’t know how broad this is supposed to be. If it’s Napolean Dynamite absurdity or David Brent in The Office type humor.

MORGAN: “Really takes the piss doesn’t it?” Charli nods with her mouth clenched. MORGAN: “Did I use that right?” So I guess this means Morgan is American and Charli is British? Not sure how I was supposed to know that before this joke.

We then segue to this completely unbelievable “emergency” whereby Morgan is concerned that Charli will be charged with her murder if she doesn’t act quickly. Not a single reader will believe that Charli is in any danger at all here so that doesn’t make sense. And then that’s the end of the scene.

Okay, so, what’s the big change we could make to this scene that would instantly improve it? You need to treat Morgan separately from the circumstances that surround her. In other words: GIVE HER SOMETHING TO DO! The big weakness in this scene is that Morgan has nothing to do. Once you give her something to do, you create conflict, and now you have a scene.

It could be something simple – she has to get to work. Brandon even hints at this with the Boss Bitch call. But he doesn’t do anything with it. DO SOMETHING WITH IT. Make this the biggest work day of the year for her. She’s got some big presentation or something. And she’s only got several minutes to get ready and sprint across town if she’s going to get there on time.

Imagine how much more energy the scene would have. Morgan gets up and rushes to get ready. She notices these weird anomalies but she’s half asleep and ignores them. The jokes have a little more zing to them because there are now consequences to problems that come up. If she can’t change clothes, she’s fucked. So what happens when she can’t grab new clothes?

After doing the best job she can, she rushes to leave, and that’s when Charli shows up. Instead of needing to piss like a racehorse, the jokes are now built around Charli’s shock at Morgan’s appeareance. Morgan is trying to run around her to get to work and Charli’s trying to stop her because she looks terrifying. During that conflict that the two have, Charli’s eyes finally pop as she stares across the room. Morgan turns around to see what she’s looking at, and that’s when she lays eyes on her dead body for the first time.

Would this fix all the problems in the scene? No. But there’s a “lazing-around” quality to the scene now that this would definitely improve. Then there’s clarity, which is an issue in about 10% of the moments in this scene. Like I said, when it comes to comedy, there can be zero clarity issues.

I’m not finding the jokes funny. I do know that jokes are funnier when there’s more pressure. And Morgan’s entire career depending on this presentation would place a lot more pressure on the importance of her getting ready. But I still think we need a lot more thought and creativity put into the jokes. It doesn’t seem to me like we’re trying our hardest in that area.

I want to thank Brandon for so bravely entering his scene in the Slaughterhouse. There are ZERO hard feelings here. But I wanted to take you into the frustration in my mind because this is what readers often feel when they read a scene that isn’t working. And I’m hoping that honesty helps all of us understand how high the bar is. It’s always higher than you think!

Longtime commenter, Grendl, takes home an easy win on the third screenwriting showdown of the year!

I was initially quite down about Scene Showdown because I was reading 20, sometimes 30, entries in a row and not finding even a single respectable scene. To that end, I’m very thankful that Grendl entered the competition because as soon as I saw his e-mail address, I knew he was going to give me a quality entry. And he did.

To be honest, it provided a sigh of relief because I was starting to worry that I wouldn’t have enough entries to create a showdown. And, just to be clear, my frustration is not on you guys. It’s on myself. If the scenes you chose to enter are not up to par, then it’s something I’m doing wrong. I’m not conveying to you what constitutes a good scene. I’m not conveying to you how to write a good scene. These days, I consider myself a guide, a teacher of sorts, and that means if the entries fail, I failed.

I would like to get into why the entries didn’t work in a more aggressive manner because I think that soft-peddling criticism has, maybe, made writers believe script issues are less problematic than they are. But I need your permission to do so. So, if you entered a scene that didn’t get chosen and you want it to go through the Carson gauntlet, let me know in the comments. Cause I feel like if I’m more aggressive with my analysis, it has a better chance of sticking.

Okay, let’s get on to today’s winner, which won by a whopping 10 votes, Grendl’s scene from his script, “Undertow.”

The first thing I’m going to praise here isn’t sexy. But as I learned, after going through all these entries, it is by no means a given. Which is that the writing is simple and easy-to-understand.

Veronica approaches the intercom, spotting the faded listing behind a glass pane. She scans the list of names, but doesn’t see his. There is one button with no name next to it. She presses that one.

There’s no pretentious overly-complex description here. The writing tells us exactly what’s going on and nothing more. When there’s an opportunity to add detail (“spotting the faded listing behind a glass pane”) it’s taken. But there isn’t anything in the description that makes me double-take because it was unclear.

Yet this issue was prevalent in nearly all of the submissions. I don’t know what it is about writers but they seem to seek out the most awkward ways to describe things possible.

This was a huge issue while I was picking entries. I couldn’t even get to the point where I was judging the scene because I knew that if I put something up that had a sentence like, “In no uncertain manner as the buttons bloom with faded blue light, the intercom from which Vernoica has approached, in dire need of being replaced, responds to the index finger she presses upon it, the one button without a name…” that the entry would get hammered.

If we’re not even getting basic sentence-structure right, how can we expect to tell a compelling story? Grendl’s writing was simple and to the point. It allowed me to focus on the story and the story alone.

And I liked what Grendl did right away with the scene. We establish this trust and rapport between driver and passenger, with our driver promising he’ll wait around. And then Veronica barely makes it a step out of the car before the driver zips away. I like moments like this because they establish that unexpected things can happen at any moment.

This is so important in a genre like this because you need the reader to feel unsettled. If they feel too comfortable reading a scene like this, you haven’t done your job. So even before my protagonist moves into the dangerous situation, I’m already on edge.

The conversation that follows between Michael and Veronica is solid but unspectacular. It mostly deals with logistics (who are you, oh okay, you can come in) and I probably would’ve added more resistance on Michael’s end to create extra tension. Especially because this is no longer just about meeting with this man. It’s about how, if she doesn’t get into this building, she’s in danger. This is a strange scary neighborhood at night and she’s a lone girl.

So for the conversation to go that smoothly was a missed opportunity. Then again, I don’t know enough about the story to understand the context of this conversation. So maybe it makes more sense than I’m giving it credit for. These are the challenges with scene showdowns. The reader doesn’t have all the information.

Once in the building, Grendl knows to ratchet up the tension and the potential danger. He knows that you don’t want to just throw Veronica into the elevator right away. You want to build suspense. So the stuff about the elevator lurching into motion, “rattling and screeching its way down,” is good.

Remember that the original need for a written screenplay was to convey to the people working on the film what it was we’re going to see onscreen. That mission has evolved over time, as screenplays require the pages to be more entertaining. But everything goes back to that.

And Grendl achieves that here. I’m seeing this movie on the screen as I read it. Cavernous hallways, echoing footsteps, looming shadows. And none of this is overbearing or overwritten. It’s just enough to get an idea of what we’re looking at, and then we’re moving forward.

The scene gets another jolt when the elevator doors open and Veronica realizes there’s someone inside. One of the things I talk about in my latest book is this idea of leaning into common situations. The first instinct writers have is to avoid common situations behind the logic that they’re “cliche.”

But certain situations are dramatically dependable because they are RELATABLE. Every woman knows what it feels like to get into an elevator with a man who looks sketchy. And men know this too! Even if they haven’t experienced the scenario themselves, they understand how the situation would feel to a woman.

So, you have this baked-in tension powering the sequence. Even if you did nothing with this setup, it would provide the scene with an adequate amount of conflict. Of course, the writer’s job is to play with the scenario and create even more conflict with it. Which is exactly what Grendl does.

By the way, this section could’ve been described better. Veronica initially hesitates when she sees that there’s someone on the elevator. We’re then told the man “presses the button,” and she gets on. But what button did he press and what does it do? A few lines later, we’re told about a “DOOR OPEN” button so I guess that’s what he’s been pressing. But since the average elevator doesn’t require someone to hold a ‘door open’ button, that probably needs to be described up front.

And yet, it doesn’t matter. I’m already hooked on the scene. My suspension of disbelief is strong because of the way the scene’s been set up.

When you do that as a writer, readers DON’T CARE about this button stuff. I’m only pointing it out because this is an analysis of the scene. But if I was just reading this to enjoy it, this moment wouldn’t bother me at all because it doesn’t affect the core elements of the scene, which are working.

If this scene would’ve been bludgeoned in its setup, then the button qualm becomes indicative of a larger issue. So, get the dramatic stuff right and it won’t matter if you make little mistakes here and there.

Next, we get this fun little moment where the strange elevator man presses the basement level button instead of the 3rd floor button. So we’re going in the opposite direction of where we want to go. This is Suspense 101. You want to imply that something dangerous is coming and then sit in the anticipation of it. This is what directors such as Alfred Hitchcock were so good at.

There were very few writers who submitted to the Scene Showdown who understood anything about suspense. So, opportunities like this were overlooked. I just want to make it clear to people WHY this scene was chosen over other scenes. And an understanding of basic dramatic screenwriting, stuff like how to properly implement suspense, was a big reason.

My only real criticism of the ending is cutting directly to the third floor. I probably would’ve sat in the elevator as it ever-so-slowly ascended away from that basement, away from the danger of this man, to allow our heroine to finally let out a relieved sigh. Then follow her, in real time, up to the third floor, the elevator doors opening, and her trying to find Michael’s door.

She starts looking around. None of the doors have numbers on them so she has no idea where to go. And then, of course, as has already been written, she hears the elevator moving back to the basement floor. The scary man is coming back up. She’s got to find Michael’s door ASAP. She does just in the nick of time. End of scene.

Very strong entry. This is the scene I probably would’ve voted for as well.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[xx] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: The scene is a great reminder that even small goals, such as your hero trying to get to an apartment in a building, can be compelling if you add the right mix of dramatic ingredients.