Search Results for: the wall

The Spec Market has been on life support for awhile now. Some of this is due to things beyond our control – IP Superhero movies taking over the bulk of high-budget studio output (gone are the days of original titles like Men in Black). But an equal amount of blame should be placed on our shoulders. We haven’t been writing good screenplays. I mean, here are the top 10 non writer-director non-true-story spec scripts turned movies of 2017.

Girls Trip $115 mil – 89% RT

The Hitman’s Bodyguard $75 mil – 39% RT

Happy Death Day $53 mil – 70% RT

47 Meters Down $44 mil – 54% RT

Fist Fight $32 mil – 26% RT

Kidnap $30 mil – 36% RT

Life $30 mil – 67% RT

The House $24 mil – 16% RT

Wish Upon $14 mil – 17% RT

The Founder – $12 mil – 83% RT

When your fifth biggest spec-turned-film of the year is FIST FIGHT??? The system’s, shall we say, down for the count. I mean, imagine having to watch all of these movies in a row. It’s the fast food equivalent of eating luke warm chicken McNuggets, a stale shell taco from taco bell, mealy orange chicken from Panda Express, a six inch dry turkey sub no mayo from Subway, a day old chocolate donut from Dunkin Donuts, just the sauce from KFC’s latest tangy chicken coating offering, a Jr. Whopper, anything off the Long John Silver menu, a Domino’s Pizza hot wing, and a chili cheese dog from Wienerschnitzel, all in a row.

Man that analogy was WAY too specific. But you get the point.

Why have spec scripts gotten so bad? Well, remember that the big dogs, the David Goyers and David Koepp’s of the world, are pulling in 7 figures for assignment work, which means they’re not bothering with spec scripts. This leaves the bulk of the spec playing ground to newbies and low-rung screenwriters, those whose understanding of the craft is still in the early stages. Hence, they’re not as likely to write something great.

Another problem is that the better low-rung writers like to write in prestige genres (read: unmarketable) like drama, period, and true story. That leaves even fewer good writers who like fun popcorn genre material. I mean, let’s be honest. A movie like Kidnap gets made because it’s fast-paced, has an easy-to-understand high stakes premise, and can garner a name actor you can throw on a poster. That’s how all those Liam Neeson thrillers got made as well. But how many writers out there actually want to write Kidnap or The Commuter? Not many. So the pool of writers writing these cheap but marketable premises is few. And the quality of the output is a reflection of that.

The formula for jump-starting the spec market will come in one of two forms. Form 1 is a hot new writer with a super-unique voice: A Quentin Tarantino, a Diablo Cody, a Charlie Kaufman. What writers like this do is they get people excited about spec scripts again. And that has a residual effect on the market. It also inspires other writers to write in a similar fashion, and you have agents and producers trawling through the copycat material to take advantage of this new avenue of getting movies made.

The closest we’ve had to this lately is Max Landis. But Landis’s voice is reflected more in his social media output than his screenplays. We haven’t had a true unique voice game-changing screenwriter in awhile now so we’re due for one. I hope he’s one of you guys. Cause the sooner that writers starts making waves, the sooner the spec world heats up again.

Form 2 is we need two non writer-director spec scripts to be surprise successes at the box office within a few months of each other. It has to be two. If it only happens once, Hollywood will call it a fluke. But twice is the beginning of a trend. This almost happened with the success of spec script, John Wick. But there was no follow-up to make it a trend. Also, John Wick is a weird example, since the first film did reasonably well, but not bonkers well. It was more what they did with the second movie that elevated the franchise, and by then the buzz of John Wick as a spec was long gone.

With the way the industry is being run now, here’s where I’d say you should focus to become the writer of one of these surprise hits. REAL WORLD ACTION. GuyOrGirl-with-a-gun movies (John Wick, Jason Bourne), GuyOrGirl-in-a-car movies (Fast and Furious), Government agency-movies (new takes on James Bond). Or, SOME REAL WORLD VARIATION of these that isn’t out there yet. And that’s probably going to be the most likely avenue for success, since it will be new and fresh.

Here’s why those worlds specifically. Right now, Hollywood’s got its big-budget fantasy and science-fiction slots taken care of. They’ve got superheroes and Star Wars. Those are the most expensive movies to make. So they’re only going to spend all that money if they’ve got intellectual property awareness that’s through the roof. They’re not going to spend it on your unknown 300 million dollar sci-fi movie idea, “Space Wagons in the Milky Way.”

Real world stuff is cheaper to make and due to the way action travels, it’s not as important that the material be based on IP. But guys, there’s a rub to this. I’d go so far as to say a danger in it. Action movies are almost, by definition, generic. Tough guys saying tough things while either shooting a gun or driving a car isn’t interesting. If you’re going to write a great spec script in this arena, it will need to excel in some area. The characters will have to be deeper and more interesting than we’re used to. The set pieces will have to be stuff we’ve never seen before. The concept will need to be clever in some fresh way. The narrative will need to take us in directions we weren’t expecting.

Some of you might be wondering why I’m not mentioning horror. Get Out. Split. Keep in mind that both of those were writer-director specs. So they’re not as applicable. However, you’re right in pointing out that those types of scripts DO sell. The issue is more in how the industry sees these specs. Horror will always be seen as small potatoes. So the amount of money even the biggest horror specs garner will never be enough to jump start the spec market. For that, we need big money sales, and those are more likely to come from higher budgeted films.

The last sleeper arena I’d say could jump start the spec market is a really clever sci-fi premise that doesn’t cost too much (but also doesn’t cost too little). Remember, The Martix was shot for just 60 million dollars. Why? Because their premise cleverly allowed them to shoot 90% of the “science fiction” in real-world locations. If you can come up with a premise like that? Which promises something cool at a reasonable budget, that’s worth exploring. Ditto if it’s fantasy (this is basically what they did with Bright).

Keep in mind that the advice I’m giving here is SPECIFICALLY geared towards selling specs that could then get turned into big movies which would then jump start the spec market. There are other ways to succeed as a screenwriter. For example, if you care more about writing one of Disney’s Star Wars movies than you do selling a script, maybe writing “Space Wagons in the Milky Way” (with a better title, of course) is the route to go. If the script gains some traction and gets in the hands of Disney folks, there’s no reason to think you couldn’t get a meeting with the Mouse House.

Ditto if you want to be thought of for the next Wolf of Wall Street job. Write a big fun Scorsese type movie about flashy subject matter and flashier characters that takes place in one of the previous six decades. Show them that’s your wheelhouse and if the script is good, you’ll get meetings for that kind of stuff.

But if we’re going to jump start the spec market, it’s going to happen in one of the two ways I listed above. It’s up to you whether you want to follow that advice or carve your own parth. Whatever the case, I’m rooting for you. :)

A quote doesn’t always become part of the screenwriting lexicon because it deserves to. A lot of times, a quote becomes famous simply because it sounds good. And there’s nobody better at creating sexy-sounding quotes than writers. I mean, that’s their job, right? So today I wanted to sift through some of the sexiest writing quotes throughout the years and determine which advice is actually good, and which you should ball up and toss in the wastebasket.

“If you want to send a message, go to Western Union.” – This was uttered by a famous studio head in the Golden Age of Hollywood in response to screenwriters who argued that their stories should be about more than surface-level entertainment, that their movies should actually contain a theme, or “message.” Here’s the thing about this piece of advice. I think what the studio head was referring to wasn’t themes in screenplays. He was responding to bad writers clumsily executing over-the-top themes in screenplays. Of course your script should be about something. But if you’re on-the-nose and clumsy with the way that theme is executed, people aren’t going to respond well. As is the case with most aspects of screenwriting, you must integrate the component invisibly.

“Every story should have a beginning, a middle, and an end. But not necessarily in that order.” – This was one of the most famous screenwriting quotes to come out of the 90s, and it was born out of the success of Quentin Tarantino, specifically Pulp Fiction. The advice itself is fine. But it set a bad precedent to aspiring screenwriters, encouraging them to write these wild out-of-sequence narratives before they knew how to tell a simple story. Who cared about a narrative spine, stakes or compelling characters when you could rapidly cut back and forth between disparate storylines? As such, I would be wary of this advice. Learn to tell simple stories first and then move on to more complex narratives like Pulp Fiction.

“Kill your babies” – This popular piece of advice has been around for half a century, and the idea behind it is simple. Writers – especially beginner screenwriters – believe that every thing they write down on the page is gold. As in, once it’s there, it cannot be erased. Ever. To be a great screenwriter, you must be willing to eliminate that character, that scene, that subplot, that dialogue exchange, if it doesn’t keep the story moving forward. This is the essence of “Kill your babies.” You have to be a harsh editor. This advice was relevant when screenwriting was invented, and it will be relevant for as long as screenwriting is around.

“A professional writer is an amateur who didn’t quit.” – I remember when I first heard this quote and it kind of blew my mind. You can’t fail if you never give up. Death is literally the only thing that can stop you. But I do think the quote is dangerous. There are people who are 15 years into their pursuit of screenwriting (or whatever artistic endeavor they’re pursuing) who aren’t living productive lives. You have to be smart about it. As you get older and “adult” responsibilities creep in, you shouldn’t be hedging every aspect of your life on selling that big screenplay. It’s cute at 25. Not at 35. However, the awesome thing about writing is that it’s the cheapest of all the artistic pursuits. So make sure you’re giving the rest of your life ample attention and squeeze in time to write after those duties are over. As long as you love to write, there’s no reason to stop.

“Always ask yourself, what’s the worst thing I can do to my hero right now? Then do that.” – There are a lot of variations of this quote. Another comes from Kurt Vonnegut: “Be a sadist. No matter how sweet and innocent your leading characters, make awful things happen to them—in order that the reader may see what they are made of.” One of the biggest mistakes young writers make is that they’re too kind to their protagonists. Every aspect of their journey is too easy. You gotta put your protagonist through the wringer, man! For the exact reason that Vonnegut points out. We only find out who a person truly is when they’re faced with adversity.

“If there’s a problem in the third act, it’s because of an issue in your first act.” Of all the famous pieces of screenwriting advice out there, this is one of the ones I like the least, mainly because it’s vague. And there’s no quicker way to confuse a newbie screenwriter than to give them vague advice. I think what the advice is trying to say is that if something isn’t working in your third act, it means you didn’t set it up properly. For example, if your hero kills the dragon with some potion he randomly found two seconds prior, that would’ve worked better had you set the potion up earlier. But it doesn’t mean you needed to set it up in the first act. You could’ve just as easily set it up in the second act. So the advice here is more, “If something isn’t working in your climax, you need to set it up better somewhere.” Of course, that doesn’t sound as flashy, which is one of the problems with famous quotes.

“If you show a gun at any point in your story, it must be used later.” – I agree with this one. And note that “gun” is a stand-in for any weapon. Crossbow, hunting knife, bomb. And this is mostly due to the way we’ve been conditioned by cinema. It’s happened so many times in movies before, that if you DO show a weapon and don’t use it, it’s confusing to the audience. I remember reading a script once where the writer went to great lengths to highlight this sword on a wall. He described every crevice of the thing. I was convinced it would be used later to decapitate someone. Nope. It was never mentioned again. Drove me crazy.

“If I have anything to say to young writers, it’s stop thinking of writing as art. Think of it as work.” This one comes from Paddy Chayefsky and it’s something I’ve come to appreciate more as I’ve grown older. Screenplays only reach their potential during rewrites. And, unfortunately, when you’re on your 7th draft and nothing about your story is fresh or fun to you anymore, busting the computer open isn’t as easy as it was during that stream-of-conscious rollercoaster ride of a first draft. The good writers buckle down and they get the work done, even when it’s not fun. So I totally agree with Paddy here.

“Write drunk, edit sober.” – I don’t know who said this (was it Hemingway?) but this is the very definition of what’s wrong with famous quotes. This is such a sexy quote and so fun to say but it’s terrible advice. While writing drunk is fine to do every so often, you do not want it to become a crutch. You’ll be convinced that the only way you write good stuff is to get wasted, and that’s not sustainable. However, I do like the cousin of this quote, as it captures the spirit of it in a much healthier way: “Write from your heart; rewrite from your head.” Be non-judgmental when you write. Let yourself feel things without right-braining them to death. Then, when it’s time to rewrite, bring a more logical assessment to the writing.

“Grab’em by the throat and never let them go.” – This comes from Billy Wilder and I think it’s one of the most important pieces of screenwriting advice you’ll ever hear. Too many writers put the burden of investment on the reader. “You owe me,” is how they look at writing. No no no no no. Readers don’t owe you anything. It’s up to you to keep them invested. And the second you drop that ball, whether it’s on page 1 or page 50? They’re gone. They’re done with your script and they have that right. You want to grab your reader with the very first page and then every subsequent page, ask yourself, “Do I still have them?” If you don’t think you do, rewrite the scene until the answer is yes. That doesn’t your script should be one long action set-piece. You can use mystery, suspense, foreshadowing, conflict, dramatic irony, confrontation, anticipation, an intriguing new character, and, sure, a kick-ass action scene we’ve never seen before. You have hundreds of tools available to yourself. You are in control of whether your scenes are good or boring. Never take that for granted.

Carson does feature screenplay consultations, TV Pilot Consultations, and logline consultations. Logline consultations go for $25 a piece or 5 for $75. You get a 1-10 rating, a 200-word evaluation, and a rewrite of the logline. I highly recommend not writing a script unless it gets a 7 or above. All logline consultations come with an 8 hour turnaround. If you’re interested in any sort of consultation package, e-mail Carsonreeves1@gmail.com with the subject line: CONSULTATION. Don’t start writing a script or sending a script out blind. Let Scriptshadow help you get it in shape first!

Genre: Horror/Action

Premise: When a discarded top secret military weapon resurfaces on a research ship, the crew must fight for their lives to survive the bizarre technology.

About: Cary and Chad Hayes have become Hollywood’s go-to A-List Horror writers, scripting both The Conjuring and The Conjuring 2. But that success didn’t come overnight. The brothers wrote in television for a dozen years before getting their first shot at the feature world (2005’s House of Wax) and then went almost an entire decade before they had their first major breakout hit in The Conjuring.

Writers: Cary and Chad Hayes

Details: 104 pages – 2011 draft

I’ve always wondered, how do you make a blob scary? It’s a blob, the goofiest monster ever. It doesn’t even have a personality. It’s a blob.

I like reading these scripts, though, because I’m always curious what writers pitched to win these “no-win” assignments.

For those of you who will be lucky enough to break into this business, you’ll be asked to pitch no-win takes on assignments all the time. You could say that the writers who last the longest in Hollywood are the ones who consistently come up with solid takes on bad ideas.

Remember, it was Charlie Kaufman who, tasked with adapting a book about flowers, came out the other end with Adaptation.

I personally don’t believe it’s possible to write a good Blob movie. But I’m ready to be proven wrong. Let’s see if the Hayes brothers pulled it off.

Shannon Cole is a member of a research team on the high-tech vessel, “Indigo.” Besides researching ocean life, Shannon also likes researching her hot Navy boyfriend, Colin Hawthorn, who she’s constantly trying to sneak Skype sessions with whenever possible. The two discuss how it’s only a matter of time before they can be together, sans ocean in the way.

And then a plane crashes next to the Indigo. And not just any plane, but a military plane. Members of Shannon’s team are able to save the sole survivor, a dude named Steve Walker, but they sense something is off right from the start. Especially when Steve hightails it off the ship. As in, he leaps off and starts swimming away. What in the world would cause a man to swim into an endless ocean as opposed to stay on a ship?

Answers start coming in the form of the NAVY, who radio Indigo to tell them to watch out for this Walker fellow. Oh, and to avoid any gelatinous masses that happen to have snuck on the ship. Oops, too late for that. The secret weapon that Walker stole, and which was responsible for the crash, has made its way onto the Indigo.

Once Shannon and her crew spot this thing, they begin attacking it. But it’s pointless. There’s no way to actually destroy gelatin. It just eats up their bullets, their weapons, and eventually, their bodies.

Shannon calls for help from her nearby NAVY boyfriend, but he tells her this call is above his pay grade. The military is so terrified of this blob weapon that they’re going to let it do its damage and, hopefully, disappear forever afterwards. That means Shannon and her crew will have to figure out how to defeat this thing on their own. A task they’re realizing may be impossible.

Okay, let’s approach The Blob the way any screenwriter tasked with adapting this idea would. You’ve only been given one quota: A “blob.” You can do anything you want with that, as long as there’s a blob. What do you do?

The Hayes’ brothers opted to place the blob on a ship. On the plus side, you’ve created a classic horror scenario. A monster. A contained location. A bunch of people stuck in that location.

But the first thing I asked was, “Is a research ship really the most interesting location for this concept?” Not really. You’re limited, pretty much, to your blob squirming around the hallways of a ship. I’m not sure if you’re getting the most out of the idea there. Had the Indigo been researching something that could’ve conflicted with the blob in some way, that might’ve been cool. But it didn’t. In fact, I was never clear on what this ship was researching.

Specificity guys. You have to think in terms of specifics, not generalities. Because there was nothing unique on this ship, nearly every scene was identical. People hiding in rooms. The blob banging on the door. Sometimes getting in. A battle would occur, they’d go to another room. Variety isn’t only the spice of life. It’s the spice of screenwriting. You have to differentiate your scenes. And because all the elements here were so generic, there wan’t much opportunity to change things up.

Also, the one advantage you have with a villain as unique as a blob is that you can look for things that only this specific “monster” can do, and play around with that. Take Freddy Kruger. He can haunt your dreams. So you can write a lot of cool scenes where Freddy is stalking you in your dreams, where you’re not sure if you’re asleep or awake, where he’s luring you to sleep – the kind of things that ONLY THAT CHARACTER offers to the story. That’s part of the fun of screenwriting, is finding those unique avenues that only your specific concept can provide.

But the blob never gave me that. There was one moment early where a character gets swallowed up by the blob and we watch him see the world through his POV as he’s being digested. But that was pretty much it. Otherwise it was just a blob banging away on doors and eating folks. Any monster can do that.

The best opportunity for a memorable scene came when the crew gets stuck in the shark lab. A tank full of sharks? A blob. Your team can’t leave the lab? The possibilities are endless, right? What if the blob keeps banging on the door and the shark tank starts cracking. Bang. Crack. Bang. Crack. The group realizes that either they stay in here and get eaten by sharks or they take their chances with the blob.

OR maybe the blob eats the sharks, which are swimming around in its gelatinous mass, some of their shark heads sticking out, chomping like crazy to get away, and our team now not only has to deal with a killer blob, but a killer blob of crazed sharks!

No, we don’t get any of that. Our team simply looks up after a moment and notices that all the sharks are gone. The blob has eaten them. And that’s the end of our shark lab scene.

I don’t think you can write a blob movie that isn’t a comedy. This is something you have to build a goofy premise around and then really have fun with it. I could see, for example, a group of people getting caught inside a 50s movie universe. They come to some deserted town, where they’re attacked by things like the Fog and the Blob. And you just get goofy. I could see the Blob swallowing people up, but then releasing them out later, and they become these slime-soaked blob marionette zombie things that do the blob’s bidding. Shit like that.

Trying to turn a blob into a serious action movie? I don’t see any audiences being interested in that. Feel free to offer your own blob takes in the comments section. I’m curious if anyone can actually pitch a good idea off of this.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: I learned that if you have a weird starting point – like a blob – you need to embrace that weirdness and get weird with it. To try and take a weird concept like this into straight territory is a bad idea.

Genre: Horror

Premise: A group of geologists in the Amazon stumble upon a fossil of a mysterious hand, and when they go looking for the rest of the body, get more than they bargained for.

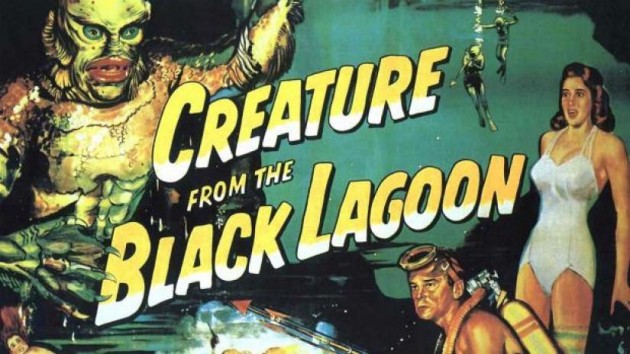

About: The birth of an idea! Mexican cinematographer Gabriel Figueroa told producer William Alland about a myth he’d heard of a race of half-fish, half-human creatures in the Amazon. Alland revisited the conversation 10 years later, thinking it would make a good movie. He wrote some story notes, which writer Maurice Zimm would later expand into a treatment. Finally, Harry Essex and Arthur Ross turned the treatment into a full-fledged script. Listen to the people in your life, guys. Ya never know where your next idea might come from. What’s interesting about this film is that it was shot and projected in 3-D. However, the year was 1954, and the 3-D fad was dying quickly (hmmm, why does this sound familiar?). The Creature From The Black Lagoon was a last ditch attempt to save the format. However, it didn’t, and most people ended up seeing the film in regular format.

Writers: Harry Essex and Arthur Ross (story by Maurice Zimm, idea by William Alland)

Details: 79 minutes

When I go through all the old scripts that have been purchased or optioned throughout the years, there are tons that never get made. However, the one genre whose purchased scripts get made the most – BY FAR – is horror. It’s crazy. Almost every old horror script I find on my hard drive has ended up becoming a movie. It’s the friendliest genre to writers out there.

While I continue to look for stuff that hasn’t been made yet, I thought I’d review a horror classic that I hate to admit I’d never seen before. In fact, I was so ignorant of this film that I thought it and “Swamp Thing” were the same movie. I need to work on my water body differentiation. But yes, when I saw this film at the top of Itunes’ Classics list, I thought, “It’s about time for me to check this out.”

For those who haven’t seen “Creature,” it follows fish scientist David Reed and his girlfriend Kay, who go on an expedition into the Amazon with a small crew of scientists to find additional information on a mysterious amphibious hand that David’s old geologist teacher, Dr. Thomas, dug up.

When they get to the dig site, they find that the two men guarding the site have been killed. Hmmm, might a modern-day version of the creature have attacked the men? Meanwhile, David’s getting agitated with one of the crew members, Mark Williams, who only seems to care about money. But since Williams is funding the expedition, David has no choice but to suck it up.

Eventually they realize that the river drifts down into a secluded lagoon, so that’s where they go looking for more fossils. David and Williams do some deep-lagoon diving, where they eventually encounter the creature. At first they want to capture the thing, but when it starts killing their crew members, priorities change. It’s time to jet. There’s only one problem. The creature has lodged a blockade into the only exit. The ship is stuck there. And it’s time for battle.

Wow, the first thing I noticed about this is how much influence it had on Spielberg. You can see a lot of the same shots that Spielberg uses. The creature’s hand, which we see throughout the first act, might as well be a shark fin. And the creature’s attack on the two natives in the tent, seen from outside, with only a bunch of shadows bustling around, had a distinctive “Jurassic Park” feel to it.

You can also see how this influenced James Cameron. I wouldn’t be surprised if he’d used this as a pseudo-template for Aliens, with the financially-motivated Williams a dead-ringer for Paul Reiser’s “Burke.”

But the big question is, does the script hold up after all these years? Yes and no. The first act moves surprisingly fast. Plot points are set up quickly and we’re off to the races without a moment to spare. Of particular interest was a scene where Dr. Thompson picks up Dave from a dive, then shows him a picture of the creature’s hand on the boat ride back to the beach.

The fact that they were combining beats (the ride back to the beach AND intro’ing the fossil to David) is proof that even back in 1954, they were looking for ways to speed the story along. I would’ve imagined that they’d wait to get the character back in a still room with everyone standing around before showing David the picture.

Where the movie runs into trouble is once they start deep-diving into the lagoon to look for the creature. I have to remember that people didn’t have the internet back then. I mean, while I was watching this movie, I was texting, interneting, and doing some work. People just didn’t do that back then. They had all the time in the world. Imagine that for a second. Going to a movie and that was your day. It was what you looked forward to, what you experienced, and what you talked about after. We just don’t do that now.

Anyway, I’m guessing underwater photography was a new toy in 1954 because any time we went underwater, we stayed there forever. How many times can you show a girl swimming and the creature creeping up and barely touching her before swimming away again? According to Creature From the Black Lagoon, a good 8 or 9. Ditto whenever the men go hunting for it. We cut endlessly back and forth between the men and the creature.

I’m guessing 1950s audiences were more tolerant of this because their attention spans were longer. But you can’t get away with that today, and it’s not just for technical reasons. It’s for story reasons. The longer you show something, the more used to it the audience/reader gets. So if you’re going to show us 50 shots of the creature on the first dive, we’re going to get used to him. And the more used to him we are, the less afraid of him we’ll be.

“It” did a nice job of this. When Pennywise comes, he comes in forms other than a clown, he’s hidden behind balloons, we’ll hear him but not see him, he’ll pop up then disappear immediately. Even in the famous opening scene, we’re only seeing his eyes. This is important. If we get used to Pennywise, he won’t be as scary.

Another issue here is that there was zero attention paid to character development. I don’t know if that was common back then, or just common in creature-features. Citizen Kane had some pretty stellar character development and that came out 13 years before this did.

But it really hurts the movie as it goes on. This is important to remember, guys. If all you’re doing is moving the plot along, it’s a bit like moving chess pieces. Things are happening. We’re getting closer to a resolution. But we feel strangely detached, and eventually bored. To keep the chess analogy going, tell us something about the people playing. That’s how you make a chess match truly captivating.

I remember an old girlfriend of mine who HATED basketball. Thought it was so dumb. She’d actually get mad at me whenever I’d watch my beloved Chicago Bulls. “I don’t see why you care so much about a bunch of guys throwing a ball in a hoop,” was a common argument-starter.

Finally, one day, I sat her down. “You don’t understand,” I said. “You see that guy there? He doesn’t believe that our coach is any good. So half the time the coach gives him a play, he ignores it. And you see that guy? He was once the worst guy on the team. But now he’s knocking on the door of being the best. Our best player, that guy with the buzz cut, is feeling that pressure. He’s afraid of being supplanted. So he doesn’t pass that guy the ball. And that guy? Our center? He’s so badly injured that he shouldn’t be playing. But he has to or else he won’t get a contract extension and probably be out of the league next year. If you watch him closely, you can see how much pain he’s in.”

She became fascinated. These weren’t just “guys throwing a ball in a hoop.” These were real people with problems and conflicts and drama! Which equals entertainment! I couldn’t keep her away from watching games with me after that.

Getting back to Lagoon, there wasn’t a more boring relationship in the last 100 movies I saw than David and Kay. It was the single most agreeable couple I’d seen on film (tip: agreeable is a BAD WORD in screenwriting). I guess no one was breaking down walls to write captivating female characters in 1954. Still, this was a major reason why the movie lost steam. We simply didn’t know enough about these people to care about them.

Which leads us to the dialogue. Most of it was written to either move the story forward (“We need to go to the lagoon!”) or to pose theories (“This could be the link between man and fish we’ve been looking for”). You’re going to have to do those things in every script. But dialogue should primarily be used to explore character.

And by that, I don’t mean each character should spout off a 50 line monologue about who they are and what their life philosophy is. I mean you need to create unresolved issues between characters and each dialogue scene should make us feel like we’re getting a little bit closer to resolving the issue.

In another water based movie, Dead Calm, a husband and wife haven’t resolved the death of their child. It’s hanging there in every scene, even if they’re not talking about it. So we know that, eventually, we’re going to get a resolution to that. That’s how you explore character.

Anyway, this was more fun than I thought it would be. But because I live in 2017 and not 1954, there were only so many things I could overlook. Still, it’s worth checking out if you have 80 minutes.

[ ] What the hell did I just watch?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the watch

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Something only stays mysterious if you give us bits and pieces of it. If you give us the whole thing and you keep showing it to us again and again, we’re going to get used to it, and eventually, bored of it. Both filmmakers that I named in this article – Spielberg and Cameron – know that well, as their films Jaws and Aliens do a magnificent job of only showing us bits and pieces of the monsters throughout.

IT’S MORE ABOUT THE CHARACTERS THAN THE PLOT

I used to think plot was the only thing that mattered. If you could follow Blake Snyder’s famous beat sheet and hit every one one of his predetermined page-targets, you’d create a mathematically perfect screenplay. Eventually I realized that where the real power lies is in creating compelling characters. If you can make us like your hero, add depth to your characters, and execute arcs for your key characters, that’s where the magical recipe for success lies. The proof-is-in-pudding moment for me was when I realized there’s no such thing as a good well-plotted movie with weak characters. However, there are plenty of good movies with weak plots but great characters (Rushmore, Flight, The Wrestler, Whale Rider). Ideally, you want both. But great characters are the deodorant that covers up a smelly plot. (bonus: Here’s a quick way to add instant character depth. CONTRAST. If the quarterback of the football team is charming and popular, there’s no contrast. But if the quarterback of the football team is awkward and shy, there is. Contrast creates instant depth).

PROSE IS ONE OF THE LEAST IMPORTANT COMPONENTS OF SCREENWRITING

I remember once spending an 8 hour day trying to get the prose just right on a single screenplay page. What I learned many years later is that no one gives a crap about your ability to write beautifully if they’re bored to tears by your story. It’s always story first, guys. Get them hooked and they won’t care how average the writing is. One of the most talented prose-writers I know started a blog a long time ago. Naturally, I was excited to read it. After a week, I never went back to it again because, while the prose was magnificent, the content was boring as f*&%. Focus on the content. That’s what readers respond to.

DON’T TRY AND BE A SYSTEM DISRUPTER

When I first got into screenwriting, all I cared about was re-writing the rulebook. I wanted to tell stories backwards, break the fourth wall, introduce an entirely new type of formatting I thought was better (I’m not kidding). As exciting as all of this was, it wasn’t getting me any better at what mattered – writing a compelling dramatic story that hooked readers and kept them interested until “The End.” If you’re trying something different because you think it will make your story better, go for it. If you’re trying something different because you’re raging against the machine, turn around and start over.

COMPLEXITY IS FOOL’S GOLD – KEEP IT SIMPLE

I can’t emphasize this enough. It’s the biggest lesson I’ve learned throughout this journey. When we start writing, not only do we want to disrupt the system, but we want to write the single greatest screenplay that’s ever been written. So we add tons of characters, lots of subplots, a timeframe that goes on for years, flashbacks, flash-forwards, a narrator or two. All you’re doing when you add these things is making your story hard to navigate, for both you and us. The simplicity of movies like Deadpool, Nightcrawler, Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, Rocky, Logan, Once, Baby Driver, Her, Get Out – that’s what you should be striving for. Yes, there are complex movies out there that are wonderful. The Godfather 2. The Shawshank Redemption. But those scripts take an amazing amount of skill to pull off – more than you realize. So save those for the second half of your career. For now, focus on writing a simple well-told story.

PRESENTATION IS MORE IMPORTANT THAN YOU THINK

I used to be of the mindset that my writing was such a gift to readers that if I made a spelling, grammar, or formatting mistake, they would look past it. Why wouldn’t they, I thought. What’s important is the bigger picture – whether the script is good or not. Now that I’m on the other side, I know that mistakes are the easiest (and quickest) way to weed out beginners. Writers who have been doing this for awhile take pride in their work and make sure that whatever they put out there is presented as professionally as possible. There are instances in the thousands of scripts I’ve read where a script was good despite a sloppy presentation. But I can count them on one hand.

DIALOGUE IS IMPORTANT, BUT NOT AS IMPORTANT AS THE SITUATION YOU COME UP WITH TO INSPIRE THE DIALOGUE

Unlike prose, good dialogue is actually important. However, beginners go about writing dialogue the wrong way, focusing on clever witty banter as opposed to the real secret to good dialogue – unresolved issues between characters. All of the best dialogue is built around two (or more) characters who have unresolved business. Sometimes they battle each other straight up on that business (John McClane and his wife arguing about their marriage when he gets to LA). Other times they keep their issues to themselves, resulting in conversations dominated by subtext (imagine two old lovers meeting for coffee for the first time in years who talk about how wonderful their lives are when what they really want to say is how much they miss each other). So focus less on trying to be Diablo Cody and more on building scenarios that inspire interesting conversation.

THE MOST POWERFUL TOOL IN SCREENWRITING IS CONFLICT

Conflict makes every aspect of your script more interesting. Conflict within one’s self. Conflict with outside forces. Conflict between people. The variations of conflict – full-on fighting, passive-aggressiveness, ignored problems, dramatic irony. Think of a script as an empty tube of toothpaste and you need to get every last inch of that toothpaste out if you’re going to brush your teeth. Put pressure (conflict) on every square inch of that tube (your script). That’s what’s going to bring out the best in your story (as well as a bright smile).

SPLITTING THE SECOND ACT IN TWO

For the longest time, the second act was terrifying to me. It was this giant 60 page black hole with no form or purpose. I would fudge my way through it on every script. Needless to say, the results weren’t ideal. However, once I learned to split the second act in two (two sets of 30 pages), writing scripts became a lot easier, especially if you map out a mid-point twist (a major event in your story that throws the plot off-kilter at the midpoint) ahead of time. Also, remember that the second act is about conflict. So if you keep throwing conflict at your hero, both from outside forces, from other characters, and from within the character, you should get out of your second act unscathed.

FIGURE OUT THE ENDING BEFORE YOU START WRITING

It’s fine if you’re anti-outline. Everyone has their own creative process. Although I’d argue that 99% of the people who refuse to outline are people who’ve never tried it. But that’s a discussion for another time. At the very least, you should have your ending figured out before you start writing. Screenplays aren’t like novels. They’re much more focused. We need to get to a very specific place within two hours. And, over time, I realized that when you don’t know where you’re headed, you get lost. And the only way to find your way back, is to write like 20 drafts. In order to save yourself a lot of time, figure out your ending first. And I promise you, writing your script is going to be a lot easier.

THE TWO BEST MINI-PIECES OF ADVICE I EVER RECEIVED WERE “SHOW DON’T TELL, IDIOT” and “MORE SETUPS AND PAYOFFS, MORON”

Both these tools are small, but they easily give you the most bang for your screenwriting buck. If you have the choice of writing a kid who can’t stop talking about his dead father or giving that same kid his dead father’s watch that he fiddles with every time he thinks of him, go with the latter. Show don’t tell. Also, the best moments in a script tend to come as a payoff to an earlier setup. One of the greatest endings in movie history, The Shawshank Redemption, builds its legendary finale off a series of payoffs (hiding the hammer in the bible, the Rita Hayworth Poster, the buried box by the tree). Just remember an important rule when using these: With great power comes great responsibility.

Carson does feature screenplay consultations, TV Pilot Consultations, and logline consultations. Logline consultations go for $25 a piece or 5 for $75. You get a 1-10 rating, a 200-word evaluation, and a rewrite of the logline. I highly recommend not writing a script unless it gets a 7 or above. All logline consultations come with an 8 hour turnaround. If you’re interested in any sort of consultation package, e-mail Carsonreeves1@gmail.com with the subject line: CONSULTATION. Don’t start writing a script or sending a script out blind. Let Scriptshadow help you get it in shape first!