Search Results for: the wall

This might be the craziest sci-fi script I’ve ever read.

Genre: Sci-fi

Premise: In a future where oceans have risen and mind-controlling aliens have taken over, a psychiatrist fights to save his family, a task that gets progressively harder when he realizes that nothing is as it seems.

About: This is a rarity these days. A big sci-fi spec sale. It comes from the writer of Oblivion, which was a cool flick that could’ve been awesome if it had a bigger sandbox to play in.

Writer: Karl Gajdusek

Details: 121 pages (8/24/16 draft)

Yaaaay!

I’m in sci-fi heaven. Not only do I get Valerian in three days but I also get to read a big sci-fi spec sale today!

And for all you Valerian pre-haters, let me just say… uh, 68% Rotten Tomatoes!

What now?

Mic drop.

BOGHHHSHAFSSHSH! (explosion sound)

Valerian for life.

Valerian is actually the appropriate movie to be talking about in regards to Courage because both screenplays appear to be batshit crazy. But could Courage actually be crazier?

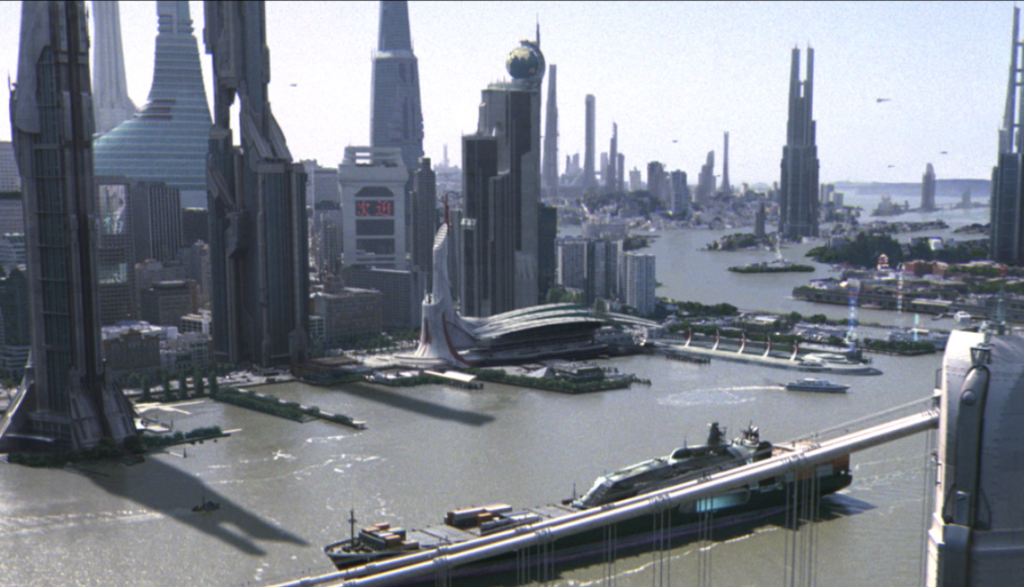

Courage opens up in a future Chicago that seems to be run like 1960s East Germany. People walk around in colorless clothes, don’t look each other in the eye, and signs like, “Remember. Two is a conversation. Three is a conspiracy,” are posted everywhere.

Jake Phobetor is a psychiatrist with a dying marriage trying to help people get through these troubling times, and after a few scenes, we learn just how troubling those times are. Chicago, it turns out, is encased in a giant glass dome that keeps out the swelling oceans which have risen due to the melting of the ice caps.

And, oh yeah, there are giant sea aliens known as the “Talis” trying to break in so they can kill everybody. Which is why there is an “Ark” spaceship that everyone’s trying to win the lottery to get on. Jake knows he’s not going to be picked, but he rigs the system to get his 8 year old son, Tash, on.

Right when they get to the ship, however, the dome breaks, and a 100 foot wall of water shoots at them. Too late for Jake and his son. Except that we CUT TO BLACK and Jake wakes up in a cryo chamber on that Ark 2 years later.

What Jake learns is that he was dreaming. Well, sort of. The Talis are real, but he and his family escaped. The reason Jake is being woken up now is because the Talis are on their tale. Their ship chased the Ark and have finally caught up. The woman who woke up Jake needs his help to pull a maneuver that will destroy the approaching Talisians.

Jake has no idea what’s going on but does the best he can, only to black out and wake up… AGAIN. Except this time he’s on a 1976 science-fiction movie set and he’s the star of the movie. It turns out that the science-fiction story wasn’t real. He’s just playing a part. Or is he?

Jake, convinced that his family is still in danger, convinces the writer to tell him how to save his wife and son, then goes back into the Ark ship to finish what he started.

One of the most important qualities a writer can have is the courage to TAKE CHANCES. If you’re not taking chances somewhere, your writing isn’t going to be very compelling.

When I used to compete in tennis, the thing that often separated the good players from the great ones was fearlessness, the ability to let loose and take chances. Go for an inside-out forehand winner when you’re down match point instead of gently pushing the ball back and hoping the other guy makes a mistake.

But here’s the thing about letting loose and ripping forehands. They don’t always go in.

And as much as I admire the hell out of this screenplay, I don’t think it lands inside the court.

It’s just too freaking crazy.

Don’t get me wrong. I was rooting for it. You guys know me and sci-fi. I’m dying for the next great sci-fi movie that’s not one of these studio assembly line doohickies. But if I’m being a fair chair umpire, I have to be honest and say this one was “out.”

In attempting to figure out where the script lost me, I’d have to say when we showed up on a movie set. As a writer, you want to be aware of the audience’s expectation. Once you set an expectation, you don’t want to betray that. In other words, you don’t want to promise an intense drama and then when people show up to see your movie, give them a romantic comedy. They’re going to be disappointed.

And this script is set up as heavy imaginative alien science-fiction. That’s the expectation I’m working with. So when we then end up on a 1976 science-fiction film set? I’m like, hmmmm. This is a huge tonal and subject matter shift. As much as I was trying to, I couldn’t get on board with it.

And that’s too bad because, structurally, the script is pretty sound. It utilizes a mystery approach in the beginning. We’re living in this strange city with strange rules and we’re trying to catch up with what’s going on. Then, right when we do, we’re thrust into this race to escape the chaos. And that’s followed by us waking up on the ship and needing to take out an imminent alien attack. So we move from mystery (what’s going on?) to a goal (get my son out on the Ark) to urgency (hurry and kill the approaching alien ship) through the first half of the screenplay and it’s all good.

But when the movie set arrives, we switch from the intensity of a man trying to save his family to problems like: How tough it is to be a movie star. It’s too radical a shift, way lower stakes, and, quite frankly, not as interesting.

Now we do jump back into Jake’s pursuit to save his family but something about knowing this is all tied to a fake movie production lessens the desire to see Jake succeed.

Also, there’s too much going on here. One of the temptations of science-fiction is to go nuts. Is to include every wild idea you have. But when there’s already a lot going on, adding more eventually leads to the law of diminishing returns.

For example, a lot of time is spent early on setting up this idea that not only are these sea aliens attempting to break through the water bubble dome, but they also have some mind-melding power where they can telepathically destroy your brain so you’re a vegetable. Even more time is put into explaining that this takes extra energy from the aliens and it will take them longer to break through the dome as long as they keep trying to destroy random human brains…

But ultimately, it’s not important. The more pressing story is a guy trying to save his family amidst an alien attack. That’s what the audience is emotionally attached to and therefore things like mind-melding brain attacks are distractions. The point is, you want to be creative and have fun in your sci-fi universe. But at a certain point you have to say, “This is the cut off point. I’m not going to keep adding more shit.”

And hey, I’m not going to pretend like it’s easy to know where that line is. It’s often a feel thing. But my recommendation to all sci-fi writers out there, is “When in doubt, cut it out.” I’m telling you, you’re going to reap the most benefits from keeping your sci-fi story as simple as possible.

With all that said, I give Gudjesek credit. This is unlike ANYTHING I’ve read all year. If you like weird sci-fi and like to be surprised, you’ll definitely want to check Courage out. I just think it’s trying to juggle too many balls at once. And for that reason, it wasn’t for me.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Improve upon sci-fi tropes – A great way to up your sci-fi game is to take a sci-fi trope and ELEVATE IT TO THE NEXT LEVEL. For example, in Courage, we have a city under a dome. We’ve seen that, right? However, Gajdusek one-ups the trope by melting the polar ice caps and having 100 feet of water on all sides of the dome. I’d never seen that before. It’s these things that give your sci-fi script a unique feel.

Genre: Sci-Fi Drama?

Premise: (from Black List) An exploration of relationships as a man witnesses different types of love across the ages.

About: This one finished pretty high on last year’s Black List. This is Tom Dean’s breakthrough script.

Writer: Tom Dean

Details: 127 pages

I didn’t make it to Baby Driver this weekend. Maybe I’ll see it tomorrow and do that script-to-screen review for Wednesday. The movie’s doing quite well, which, despite my negative script review, I’m happy about. We need more filmmakers taking chances like Wright.

Speaking of a movie that didn’t take ANY chances, The House was decimated at the box office this weekend. I’m not surprised. It always felt like a lazy idea. Plus, marriage isn’t funny. If you look at the history of comedies, marriage has never been funny.

Then there’s the new Netflix show, GLOW. I don’t know what to make of that one. I’ve watched four episodes and the writing vacillates between really good and really sloppy. The majority of the scenes feel like they were filmed before anyone knew the cameras were rolling. And the main character, played by Alison Brie (the whole reason I tuned in), is inexplicably kept in the background the majority of the time. I haven’t given up on it yet. But episode 5 better be awesome.

Moving on to today’s script, I’m surprised I haven’t reviewed it yet. It’s on the Black List. It’s time-travel. Sounds right up my alley!

The year is 1960. Sort of. This is 1960 after the invention of time-travel. Which means there’s been some changes. Subtle changes. Like futuristic shit stitched in. But changes nonetheless. It’s here where our Narrator, who will take us through the many time periods in the story, introduces himself. He explains that it’s his job to keep lovers properly meeting each other in all the various time periods.

We first get to know Cecile and Sanjay, who live in Napa Valley circa 1820. But, once again, you have to remember that just because we’re in 1820, doesn’t mean that the characters were born in this era. Both Cecile and Sanjay are from different time periods in the future, or at least, some future after 1820. We watch both of them get in a huge fight, and then we cut to New York City, circa 2402.

It’s here where Sanjay is now a young assistant at a giant company. He’s told by his boss, Henri, to deliver a gift to Henri’s wife back at their condo. Once there, however, a 50 year-old Claire, Henri’s wife, discusses happiness and love with Sanjay before ultimately seducing him.

From there, we cut to Nice, France, circa 1930, where we meet Claire as a 25 year-old. She’s just moved here, and a young cop named Antoine knocks on her door to see if she knows anything about a murder that was committed outside. Antoine falls in love with Claire at first sight, but must use his fellow English-speaking cop to translate his love for Claire.

Cut to 40 years earlier, also in Nice, France, where Antoine is now older, or maybe younger, and is now an actor. Antoine is now in love with Roland, a 30 year-old transgender man. The two fight with each other about their future, specifically how Antoine cannot be with a transgender person.

That takes us to about page 70. And I could go on. But I think you get the idea.

The original paragraph that I was going to write here, I deleted. It was too personal, too negative. And I think Dean deserves credit for his ambition. Without ambition, we get Transformers 6. There’s something to be said for artists who stand up to movies like that.

However, I can’t get past how unnecessarily complicated this story is. There’s the time-travel mythology. There’s a complex narrative. There are tons of rules. There’s no true main character. Dialogue scenes go on forever. The fourth wall is broken. It’s over 120 pages. The characters we do get are all over the place.

For example, one character is a transgender man in one time period, and then a woman when we cut to earlier in his life. Except that he’s actually living in a later time period when he’s younger. It’s almost like the writing is done to specifically confuse us rather than entertain us.

At one point, in 1960, when our characters are going to a movie, they see this on the marquee: “George Clooney in ‘11th Avenue’ Directed by Howard Hawks. His first film after time travel.”

There are also a lot of lines like this: “If it happens you’re familiar with 1820’s Napa Valley, this version won’t look familiar at all. The architecture is limited to the style and technology of early 19th century, but it is very much lived in, developed, and flourishing.”

And then we get dialogue like this: “Okay. Well, when we travel through time, we regulate exactly what dimension it is we travel inside of. That’s why when you travel from 2500 to 1500, you don’t alter the past and create a paradox that would essentially change the course of events so that your parents would never meet and thus never have you and thus never afford you the opportunity to change the past in the first place.”

When you’re reading stuff like this while attempting to follow characters backwards through time, those characters sometimes getting older despite the year being before or getting younger despite the year being after, it gets to a point where you throw up your hands. You’re rooting for scripts that take chances. But if we’re not even sure what’s going on, how can you root?

To the screenplay’s credit, it starts to come together in the end. There was a moment where I thought, “Wow, this reminds me a lot of when I first read Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind.” But whereas it was always clear in that screenplay what was going on, this one you’re in the dark the majority of the time.

The thing is, there’s a good idea in here somewhere – this concept of following love stories backwards in time. Going in reverse from each relationship to the characters’ previous relationships, and taking that further and further back until you get to the first person who started the chain. But instead we have this time travel stuff which you need Neil Degrasse Tyson next to you to explain.

So what’s the lesson here? I’m not sure. Shouldn’t new writers be taking chances like this? Isn’t ignorance, in a way, an advantage? Christopher McQuarrie stated that his best script, the one that got him an Oscar, The Usual Suspects, was written with barely any screenwriting knowledge. He said that he wouldn’t have done a lot of the inventive stuff he did had he known then what he knows now.

So why beat Dean up for that? This comes back to one of my weaknesses as an analyst, which is my defiance of experimentation. But I think my issue here is a valid one. Had their been one experimental choice, I would’ve been okay. My problem with La Ronde is that there were half-a-dozen experimental choices stacked on top of each other. And screenplays just aren’t built for that. You can get away with it in novels. Cloud Atlas comes to mind. But screenplays are limited in the types of stories you can tell with them. That’s why this didn’t work for me.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: If you’re going to write long scenes, make sure there’s enough tension to sustain them. If there isn’t, we won’t have enough patience to follow the scene through. So there’s a scene in La Ronde where Sanjay brings a gift to his boss’s wife, Claire. He is supposed to slip the gift in the condo and then leave. It is imperative he not get caught. But the extremely lonely Claire catches him, then asks him to have a drink with her. And they start talking. And then there’s more talking. And then there’s more talking. The talking goes on for a really long time. And because of all that talking that’s going nowhere, the scene loses steam. If you’re going to write long dialogue scenes like this, you need to look for ways to keep the tension. For example, what we could’ve done is had Sanjay’s boss tell him he had to be back within 30 minutes, which is barely enough time to complete the task. Then, when Claire catches him, she tells him, “Don’t worry, I won’t tell on you. If you have a drink with me.” Now Sanjay’s stuck between a rock and a hard place. He has to get back to his boss ASAP. And he has to somehow get Claire to let him leave without ratting on him. Without tension, long dialogue scenes die a sad pitiful death. If you watch any of the master’s long dialogue scenes (Tarantino) you’ll see that all of the best ones are laced with tension. And the few that aren’t, are tension-less.

The biggest mistake screenwriters make in screenwriting is starting with a bad idea. Actually, “bad” isn’t the right word. Another ‘b’ word is more appropriate. “Benign.” There’s nothing to the idea. It’s empty, uninspired, boring. And yet, 90% of the submissions I get continue to be lame and lifeless. What sucks about this is your script is doomed before you’ve even written word. And I’ve watched that play out too many times, with writers rearranging words, scenes, sentences, sequences, characters, loglines, all in the hope that their “idea” will all of a sudden work.

So what is a good idea? Well, there’s some subjectivity involved, of course. But generally speaking, people know when they’ve been pitched a good idea. Good ideas feel inspired, original, and bursting with potential. On the flip side, bad ideas feel cliched, uninspired, and half-baked. That isn’t a lot to go on as those descriptors are fairly nebulous. But don’t worry, cause I’m going to give you ten tips you can use to finally start coming up with good movie ideas. Are you ready? Let’s get started.

1) Try – This may sound like stupid advice. It isn’t. I’d say that half the ideas I’m pitched are bad simply because the writer isn’t trying. You can tell they came up with the idea quickly and haven’t thought it through. An idea has to be battle-tested. It should be pitted against at least ten other ideas you’ve been working through and emerge as the clear winner. Every time you come up with an idea, ask yourself, is this an inspired idea or is it similar to other ideas out there? Movie idea generation is the most competitive arena there is. EVERYBODY thinks they have a great movie idea, which means you’re competing against billions (with a ‘b’) of ideas. If you’re not trying your hardest, I guarantee you your idea’s bad. Here’s an example of a really well thought-out idea.

Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind – After their relationship fails, a couple undergoes a procedure to have the memories of each other erased, only to realize halfway through that they made a mistake. They then must race through every memory in their relationship to avoid losing each other forever.

2) A fresh angle/take – One of the easiest ways for me to identify a seasoned screenwriter over a newbie is a fresh take on an old premise. Newbies are still in that mindset where they’re re-writing the movies they grew up on. Veterans realize that to make an impression, they must find a new way into the movies they grew up on. One of the best examples of this is Memento, which took the old noir investigative thriller and turned it on its head.

Memento – A man with short-term memory loss utilizes a system of tattooing the clues of his wife’s murder on his body to find the man who killed her.

3) Clarity – A good idea is one where all the elements come together clearly and harmoniously. The idea is simple to understand and you’re able to imagine the movie immediately. I read a lot of ideas where the writer is throwing numerous pieces of the puzzle at us, but the pieces don’t fit together. I’ll give you two romantic comedy ideas to explain what I mean, one with a clear and powerful idea, the other with a murky and cluttered one.

Pretty Woman – A buttoned-up businessman in town for the biggest deal of his life hires an unrefined prostitute to pose as his girlfriend for the week, sparking an unexpected romance.

Aloha – An Air Force pilot returns to Hawaii to oversee the launch of a top secret military satellite while attempting to reconnect with his newly engaged ex-girlfriend as well as exploring a romance with the company woman who’s been assigned to keep tabs on him.

4) A complex/interesting main character – “I’m not interested in super hero movies or high concept stuff, Carson. Does that mean I’m screwed?” No. You’re not screwed. But, if you don’t have a highly marketable idea, you better have a compelling complex-as-shit main or key supporting character. That’s because your character will now become your pitch. Therefore, if they don’t sound interesting, that means you’re not giving us a great idea or a great character. What else is left? Are you going to wow us with your deft ability to hide exposition? Nightcrawler is a good example of this.

Nightcrawler – Louis Bloom, an unpleasant sociopathic loner with a gift for salesmanship, revolutionizes the practice of nightcrawling – taping violent accidents and selling them to news shows – by risking death every night to be the best in the field.

5) Irony – Another way for you guys who hate Hollywood movies to come up with a great idea is to utilize irony. The most basic form of movie irony is to make your hero the exact opposite of what’s required of him. So you wouldn’t write a story about an atheist who starts his own atheism support group. You’d write a story about an atheist who takes a job as a Christian preacher to make ends meet. Because irony is such a powerful element in making ideas pop, it’s another easy way to separate seasoned writers from newbies.

The Social Network – An antisocial Harvard freshman with no friends ends up creating the single largest friend network in the history of the world.

6) Strange Attractor – One of you had the perfect reaction to a recent Amateur Offerings idea. The commenter, assessing an idea that sounded like every action movie ever, said that the logline was the equivalent of “beige wallpaper.” And I thought that was perfect. You want to avoid the “beige wallpaper” version of movie ideas. One way to do this is to include a “strange attractor,” which is a unique element that stands out like a red rose in a desert. Even if your idea isn’t perfect, the strange attractor will get a reader’s attention. Say you want to write a survival movie. You can write about a man stuck on a life raft after his boat sinks, which has no strange attractor. Or you can go with something like this…

Life of Pi – When a ship transferring zoo animals to a new country sinks, a young boy is stuck on a lifeboat with a dangerous tiger.

7) Ill-equipped main character – One of the easiest ways to make your idea more interesting is to include a main character who is extremely ill-equipped for the mission at hand. This will make the character an UNDERDOG, which is one of the most salable elements in idea creation. And really, this gets to the heart of what makes any story good, which is that the journey must be difficult. What better way to make the journey difficult than to make the main character as ill-equipped for that journey as possible?

The King’s Speech – The King of England, a rampant stutterer, must overcome his speech impediment to give the most important speech in history, one that inspires the world to stop Adolf Hitler.

8) A Primary Source of Conflict – Remember guys, that a screenplay is broken down into three acts. Act 1 is SETUP. Act 3 is RESOLUTION. That leaves us with one act left. Which act is that? It’s the act of CONFLICT. A movie idea without conflict isn’t a movie idea. It’s the beginning of a movie idea. One of the reasons Hancock was so forgettable was because it only ever figured out the beginning of its idea – a drunk superhero. It needed a strong conflict to turn it into a fully-fleshed out idea.

Murder on the Orient Express – When a murder occurs on an extended lavish train ride, a detective must find the killer amongst 13 suspects before the murderer strikes again. (the conflict is the detective’s investigation – that’s what will take up the second act).

9) Genre-Mixing – This is one of the oldest tricks in coming up with fresh ideas. You simply take one genre and mix it up with another one. Since most writers tend to stay in one genre lane, the Frankensteinien results of genre mixing give way to some interesting ideas. Some of the more common genres that are mixed are horror and sci-fi, comedy and sci-fi, thrillers and horror. But don’t stop there. Get weird if you want. Mix a musical with a western. Mix adventure and film noir. At the very least, you’ll have an idea that stands apart from all that cliche garbage everyone else is coming up with. And here’s a bonus tip: The less the two genres go together, the more unique the idea will be. Mixing the romance and serial killer genres, for example.

Westworld (mixes Western and Science-Fiction genres) – A robot malfunction creates havoc at a futuristic amusement park that allows its participants to live in an artificially constructed Old West.

10) Relatively High Stakes – There’s a reason I used the word “relatively” here. That’s because not every movie is about saving the universe, nor should it be. However, the importance of your hero’s journey must contain consequences relative to that journey. Otherwise your idea sounds unimportant. One of the reasons the movie “Wild” didn’t catch on was because there were no clear stakes. A girl hikes a trail to find herself. What happens if she doesn’t find herself? Err… she’s upset? The relative stakes in that movie are non-existent. The Sweet Hereafter, another character-driven indie film, was dripping in stakes.

The Sweet Hereafter – A teenage girl who survived the most horrific school bus crash in history is the key witness in a class action suit against the state, but isn’t sure she wants to tell the truth about what happened that day.

There you have it, guys! The road map to all your future movie ideas. I encourage you to practice these tips and share the results in the comments section. The readers of this site are good at explaining why loglines or concepts aren’t working. So this is as good of an opportunity as you’re going to get at practicing idea generation and receiving valuable feedback.

If you want to get my personal opinion, I charge $25 for 200 words of feedback on loglines. I also charge $75 for a pack of 5 loglines. E-mail me at carsonreeves1@gmail.com with the subject line: “LOGLINE” to sign up. You can also hire me to consult on feature screenplays and pilots. I’ll give you $50 off with the subject header: “CONSULTATION 50.” Hope to hear from you soon!

I want to apologize in advance. I have a huge day ahead of me so I don’t have time to do a full screenplay review. Plus I’m still basking in the wonderful light of yesterday’s great screenplay. I don’t want to ruin that buzz by injecting some Max Landis script into my brain about time-traveling clowns that attack a skyscraper.

But I still want to leave you guys with a screenwriting tip.

So, I’ve been watching the second season of Aziz Ansari’s Master Of None. I’m four episodes in. For those who aren’t fans of Ansari, you should at least check out Episode 4, “First Date.” It’s a great example of what I tell you to do every day – find a fresh take on an old idea. Aziz and co-creator Alan Yang take the time worn cliche of a first date and infuse a modern spin into it. It was great.

However, the three episodes that preceded First Date weren’t very good. And as I was watching them, I was trying to figure out why. Aziz and Yang had set the first two episodes in Italy and the third, which deals with religion, back home. A common problem I noticed was that everything in these episodes felt staged. You could feel the actors reading their lines. You could see them trying to hit their marks.

For example, there’s a moment where Dev’s friend Alan comes to visit him, and the two go to the grocery store to talk. The scene was so staged and so artificial, they might as well have shown the entire production team behind them. Or there was a scene where Dev’s entire family goes out to eat at a restaurant. You could practically see the actors waiting for their turn to say their line.

At first I thought they may not have had the locations for long and had to cover everything in one take. Or the actors were still getting warmed up for the new season. But then I realized the problem wasn’t either of these things. The problem was in the writing. And it’s actually a mistake every writer makes multiple times in a screenplay.

What is it?

They hang their characters out to dry.

Hanging your characters out to dry means placing them in a scene with no purpose. No one is trying to get anything (a goal), and therefore the only thing driving the scene is dialogue. Now Master of None gets away with this better than others because Aziz and Yang write funny dialogue. But even if you’re funny, leaving your characters out to dry kills the scene.

The reason your actors’ movements and lines are so staged is because the characters don’t have any purpose in the scene. They’re literally at a supermarket, as actors, to film a scene. They’re not at the supermarket, as characters, to get anything.

The simple solution to this is to always have some kind of goal driving the scene. It could be the overall goal of the story that’s brought them to that location. Or it could be a more immediate goal that’s brought them there. The idea, then, is to have them attempt to achieve their objective, then make their dialogue secondary.

For example, there’s a later plot point where someone steals Dev’s wallet. Had you taken Dev and Alan and placed them in that same supermarket because they think the man who stole Dev’s wallet works there, now you’ve given the characters an objective in the scene. They can exchange virtually the same dialogue as they did before, but with this added element of snooping around, trying to find their man.

The thing with TV, however, is that it’s not as plot-heavy as features. So you’re not always going to have juicy plot points to play with. However, if you don’t have plot pushing the scene, make sure you have conflict. Which leads us to a second option to save your scenes: Add an issue between the two characters.

You’ll actually see this in reality TV a lot. Whenever they put two (or more) characters in a scene, they always make sure they have an issue to settle. Maybe one of them was spreading rumors. Maybe they got in a fight last night. Maybe there’s some unrequited romantic interest. Or maybe they just don’t like the way their friendship is going at the moment and want to address it. An issue gives a scene a point, as the drive to address the issue will create conflict and compel us, the audience, to see it resolved.

You never want to hang your characters out to dry. You can’t place them in a scene with no purpose. And no, exposition doesn’t count as “purpose.” Having characters talk about the big wedding that weekend isn’t entertaining. Make sure the characters either have a goal for being where they are or they have an issue to resolve. There ARE other ways to make scenes work, but these two options should take care of the majority of your scenes.

This has been a strange year at the box office. Did you know that the number 1 comedy of the year so far is the geriatric knee-slapper, Going in Style? Which has made 43 million dollars?

Surefire hits like Pirates of the Caribbean have imploded. Dusty superheroes like Wolverine have come back to life. And mega-franchises like Fast and Furious are doing two-thirds of the local business they used to, with studios not giving a shit since all they care about now is global.

Now, if we’re being honest, none of these movies I’ve mentioned affect you, the screenwriter reading this website. The writers who write these films have fought their way up a Game of Thrones like ladder that, hopefully, one day, you’ll find yourself climbing as well.

But right now, all you want to do is get your foot in the door, preferably in as little time as possible. And there are three ways to do that. The first is to write a great script that features either a great concept, an exceptional understanding of character development, or a unique voice, and parlay that into a high Black List showing. This will get you an agent and get your script out to a bunch of people so that everyone knows your name.

The second is to write a spec in one of the big genres (action, adventure, sci-fi), which might get you a starter writing gig on one of the franchises your script is written in. You probably won’t get a credit but you will be working. This is what happened, for example, with Nicole Perlman. She wrote a spec about the Challenger shuttle crash, and that allowed her to get first shot at another “space” gig, Guardians of the Galaxy (Perlman did manage to get that credit and is now scripting Captain Marvel).

Finally, there’s the third – and fastest – way to break in. Write a horror spec and direct it yourself. This is, by far, the quickest way for a screenwriter to get into the industry. I’ve seen it time and time again. The Duffer Brothers, the guys who did Stranger Things? Their breakout spec was a horror flick called “Hidden” that they directed right before the now famous Netflix show.

Even if directing doesn’t interest you, consider making it interest you. It’s so freaking cheap to make a movie these days. It’s still relatively expensive, I guess. But if the wannabe writer-directors of the 90s who had to scrape together a million bucks to shoot a film on 16mm time-traveled to today and saw how cheaply we could make a good-looking feature film? They would scold us for the excuses we make not to.

All of this is somewhat roundabout to today’s article focus. But I promise it will come together at the end. In regards to writing horror films, there were two horror films this year that took big risks, each coming at the genre in a unique way. One of those went on to become one of the most profitable films in history. The other didn’t even make it to its second weekend. And I want to discuss why one sailed and the other failed, despite the fact that both scripts were good.

The surprise hit was Get Out (script review), which has currently grossed 175 million dollars.

The unfortunate dud was A Cure For Wellness (script review), which made 8 million dollars.

Here’s another shocker. A Cure For Wellness was directed by a 20 year veteran director who had helmed some of the biggest movies in Hollywood. And Get Out was directed by someone who had never directed in his life. Not even a short movie.

Both of these projects did what I tell you guys to do: Find a fresh angle into a genre. The horror genre has ghosts, zombies, vampires, torture porn, contained horror, and they play those cards over and over again. What are you going to do that makes the genre feel fresh?

A Cure For Wellness is about a businessman who goes to a faraway bizarre treatment center to retrieve a co-worker for the company and gets stuck there. Get Out is about a black man who goes to meet his white girlfriend’s parents for the first time. As you can see, the stories share some DNA. Hell, they even both have a scene where a car hits a deer (seriously, screenwriters, please stop writing this scene).

So why is it that 20 times as many people chose to see Get Out as did A Cure For Wellness? Don’t give me the cheat answer. “A Cure For Wellness looked dumb, Carson. Get Out looked good.” One of your jobs as a screenwriter is to understand SPECIFICALLY why movies do well and why they fail, so that you can use that knowledge to make a more informed decision when coming up with your next concept.

The number 1 screenwriting mistake I see, by far, is misconceived concepts. Concepts that aren’t movies but that screenwriters, for some reason, think are movies. You guys see a few of them every Saturday on Amateur Offerings. So the large majority of you reading this have made far worse miscalculations on your concepts than A Cure For Wellness. Why is Get Out the better concept? Why is it that when people saw the Get Out trailer, they wanted to see the movie whereas when they saw the A Cure For Wellness trailer, they didn’t?

I’ll give you a hint. There’s one other film this year that defied expectations in a big way. Logan. The Wolverine franchise was dead. The movies sucked. No one was showing up anymore. Then Logan comes out and does 100 million more than the last film off a much smaller budget. How did it accomplish this? What did it do differently? Think…

The answer, if you guys haven’t figured it out yet, is that Get Out focused on character. A Cure For Wellness focused on plot. When you watch the Get Out trailer, you see a human situation, a loving but difficult relationship, then later that relationship in danger. When you watch A Cure For Wellness’s trailer, there’s a wall between you and the characters. Hell, you don’t even know the main character after you’ve finished the trailer. You see his face. You know he has to get somebody. But you don’t know anything about him. Therefore you don’t care about him. Therefore you have no interest putting up your hard-earned money to find out if he succeeds or not.

I said I’d get to the point eventually so I will. If you want to break in as a screenwriter – the fastest way to do it is to write a horror spec EXPLORING THE HUMAN CONDITION IN SOME WAY and then direct it yourself. Plot is important. But audiences don’t connect with plot. They connect with people who experience the same life problems that they do. Which brings us right back to yesterday. Vivien is such a dark script. It has its own challenges in drawing an audience but that is exactly the kind of chance you should be taking. Not writing some silly horror movie. Write a horror movie where you’re deeply exploring people and the human condition. This is how you connect with audiences.

Now there’s a caveat to this. You have to understand how to do good character work. You can’t just show two people in a relationship have a fight and think you’ve done your job. You have to find a theme, you have to create conflict within the characters (Am I good enough for this girl?), conflict within the key relationship (race), characters have to arc. That stuff takes practice. But once you understand this stuff, you become a screenwriting superhero. You can now do things that 99.999999% of the population cannot. So that’s my advice to you guys today.

But ONLY if you want to get into this business quickly.

Write a horror spec EXPLORING THE HUMAN CONDITION IN SOME WAY and then direct it yourself.

Good luck!