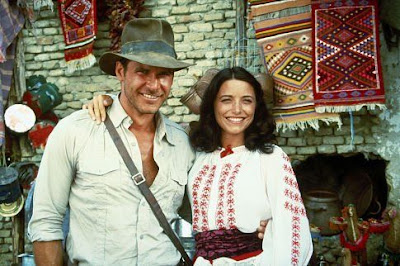

A couple of weeks back I posted my “10 Great Things About Die Hard” article and you guys responded. To quote Sally Fields: “You loved it! You really loved it!” Since I had so much fun breaking the movie down, you can expect this to be a semi-regular feature, and today I’m following it up with a film I’ve always wanted to dissect: Raiders Of The Lost Ark.

When it comes to summer action movies, there aren’t too many films that hold a candle to the perfectly crafted Raiders. Many have tried, and while some have cleaned up at the box office (Mummy, Tomb Raider

) they haven’t remained memorable past the summer they were released.

So what makes Indiana Jones such a classic? What makes this character one of the top ten movie characters of all time? Here are ten screenwriting choices that made Raiders Of The Lost Ark so amazing.

THE POWER OF THE ACTIVE PROTAGONIST

At some point in the evolution of screenwriting, a buzz word was born. The “active” protagonist. This refers to the hero who makes his own way, who drives the story forward instead of letting the story drive him. I don’t know when this buzz word became popular exactly, but I’m willing to bet it was soonafter Raiders debuted. One of the things that makes Indiana Jones such a great character is how ACTIVE he is. In the very first scene, it’s him who’s going after that gold idol. It’s him driving the pursuit of the Ark Of The Covenant. It’s him who decides to seek out Marion. It’s him who digs in the alternate location in Cairo. Indiana Jones’ CHOICES are what push this story forward. There’s very little “reactive” decision-making going on. And the man is never once passive. The “active” protagonist is the key ingredient for a great hero and a great action movie.

THE ROADMAP TO A LIKABLE HERO

Indiana Jones is almost the perfect character. Believe it or not, however, it isn’t Harrison Ford’s smile that makes Indy work. The screenplay does an excellent job of making us fall in love with him, and does so in three ways. 1) Indiana Jones is extremely active (as mentioned above). We instinctively like people who take action in life. They’re leaders. And we like to follow leaders. 2) He’s great at what he does. When we see Indiana cautiously avoid the light in the cave, casually wipe away spiders, or use his whip to swing across pits, we love him, because we’re drawn to people who are good at what they do. And 3) He’s screwed over. This is really the key one, because it creates sympathy for the main character. We watch as our hero risks life and limb to get the gold idol, only to watch as the bad guy heartlessly takes it away. If you want to create sympathy for a character, have them risk their life to get something only to have someone take it from them afterwards. We will love that character. We will want to see him succeed. I guarantee it.

ACTION SEQUENCES

When you think back to Indiana Jones, what you remember most are the great action sequences. Nearly every one of them is top notch. And there’s a reason for that. CLARITY . Each action sequence starts with a clear objective. Indiana tries to get the gold idol in the cave. Indiana must save Marion in the bar. Indiana must find the kidnapped Marion in the streets of Cairo. Indiana must destroy the plane that’s delivering the Ark. It’s so rare that we see action sequences these days with a clear objective, which is why so many of them suck. Look at Iron Man 2 for example. What the hell was that car race scene about? We have no idea, which is why despite some cool lightning whip special effects from Mickey Rourke, the scene sucked. Always create a clear objective in your action scenes.

REMIND YOUR AUDIENCE HOW DIFFICULT THE GOAL IS

High stakes are primarily created by crafting a hero who desperately wants to achieve his goal. I don’t know anyone who wants anything as much as Indiana Jones wants that Ark. But in order to build those stakes even higher, you want to remind the audience just how important and difficult it will be for your hero to achieve that goal. For example, there’s a nice little quiet scene in Raiders right before Indiana goes on his journey where his boss reminds him what finding the Ark means. “Nobody’s found the Ark in 3000 years. It’s like nothing you’ve gone after before.” It’s a small moment, but it’s a great reminder to the audience. “Whoa, this is a really big freaking deal.”

IGNORE THE RULES IF IT SUITS YOUR STORY

Part of becoming a great screenwriter is learning when rules don’t apply to the specific story you’re telling. Each story is unique and therefore forces you to make unique choices. One of the commonly held beliefs with any hero journey is that there must be a “refusal of the call.” When Luke is given the chance to help Obi-Wan, he backs down, “I can’t do that,” he says. “I still have to work on the farm.” Indiana Jones, however, never refuses the call. And Raiders is a better movie for it. Because the thing we like so much about Indiana Jones is that he’s gung-ho, that he’s not afraid of anything. So if the writers had manufactured a “refusal of the call” moment, with Indy saying, “But I have to stay here and teach. I have a dedication to the university,” it would’ve felt stale and forced. So whenever you’re trying to incorporate a rule into your story that isn’t working, consider the possibility that you may not need it.

GIVE A GREAT INTRO TO YOUR FEMALE LEAD

I can’t tell you how many male writers make this mistake (and how many female writers make this mistake in reverse). You need to put just as much thought into your female lead’s introductory scene as you do your male’s. Raiders is a perfect example of this. Indiana Jones has one of, if not the, greatest introductory scene in a movie ever. If you don’t give that same dedication and passion to Marion’s introduction, she’s going to disappear. That’s why, even though her entrance doesn’t compare to Indiana’s, it’s still pretty damn good. We have the great drinking competition scene followed by the battle with German/Nepalese thugs. The girl is badass, swallowing rum from a bullet hole leak in the middle of a life or death battle! Always always always give just as much thought to your female introduction as your male’s.

ADD IMMEDIACY AT EVERY TURN

The pace of Indiana Jones still holds up today, 25 years later. Not an easy task when you’re battling with the likes of Michael Bay and Steven Sommers, directors who have ruined audience’s attention spans with their ADD like cutting. Raiders achieves this pace not through dizzying editing tricks, but through good old fashioned story mechanics, specifically its desire to add immediacy to the story whenever the opportunity arises. Take when Indy arrives in Cairo for example. The first thing he’s told when he gets there is that the Germans are close to finding the Well of Souls! What?? This was supposed to be a simple one-man expedition! Now he’s in direct competition with a team of hundreds of men??? Because of this added immediacy, the stakes are raised and Indiana’s pursuit of his goal is more entertaining. So always look to add immediacy to your action movie where you can!

IF YOU HAVE A BORING CONVERSATION, INJECT SOME SUSPENSE INTO IT

You are always going to have two person dialogue scenes in your movie. These scenes can get very boring very quickly, especially in an action film. There’s a scene after Indy and Marion get to Cairo where they walk around the city. Technically, we don’t need this scene but it does help establish the relationship between the two, which is important for later on. Now a lesser writer may have sat these two in a room and had them divulge their pasts to each other in a boring explosion of exposition. Instead, Kasdan has them walking around, and *cutting to various bad guys getting in position to attack them.* This adds an element of suspense to the conversation, since we know that sooner or later, something bad is going to happen to our couple. MUCH more interesting than a straight forward dialogue scene between your two leads.

MOVING ON FROM DEATH IN AN ACTION MOVIE

Many times you’ll run into an issue where a major character in your movie dies. Yet you somehow must make us believe that your hero is willing to continue his journey. The perceived death of Marion creates this problem in Raiders. The formula to solve the problem? A quick 1-2 page scene of mourning, followed by the hero being placed in a dangerous situation. The mourning shows they properly care about the death, then the danger tricks the audience into forgetting about said death, allowing you to jump back into the story. So in Raiders, after Marion “dies,” Indiana sits back in his room, depressed, then gets a call from Belloq. The dangerous Belloq questions what Indie knows, followed by the entire bar prepping to shoot him. After that scene you’ll notice you’ve sort of forgotten about Marion, as crazy as it sounds. This exact same formula is used in Star Wars. Obi-Wan dies, we get the quick mourning scene on the Falcon, and then BOOM, tie fighters attack them, seguing us back into the thick of the story.

INDIANA’S ONE FAILURE – CHARACTER DEVELOPMENT

Raiders is about as perfect a movie as they come. However, it does drop the ball on one front. Indiana Jones is not a deep character. Now because this is an action movie, it doesn’t really matter. However, I’d argue that the script did hint at a character flaw in Indiana, but ultimately chickened out. Specifically, there’s a brief scene inside the tent when Indiana discovers Marion is still alive. This presents a clear choice: Take Marion and get the hell out of here, or keep her tied up so he can continue his pursuit of the Ark. What does he do? He continues his pursuit of the Ark. This proves that Indiana does have a flaw. His pursuit of material objects (his work) is more important to him than his relationships with real people (love). However, since this is the only true scene that presents this flaw as a choice, it’s the only time we really get inside Indiana’s head. Had we seen a few more instances of him battling this decision, I think Raiders would’ve hit us on an even deeper level.

Tune in next week when I dissect Indiana Jones and The Kingdom Of The Crystal Skull!

Winning….

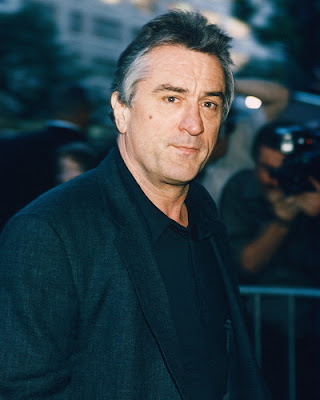

Genre: Thriller

Premise: (from IMDB) Centers on a psychologist, and her assistant, whose study of paranormal activity leads them to investigate a world-renowned psychic.

About: Red Lights is the follow-up effort of Rodrigo Cortes, the director of Buried. Not only is Cortes directing the movie, but he also wrote the screenplay. The cast is a good one, including Cillian Murphy, Sigourney Weaver, Robert De Niro, and new breakout star after her performance in Sundance darling, Martha Marcy May Marlane, Elizabeth Olsen. The movie started shooting a couple of weeks ago.

Writer: Rodrigo Cortes

Details: 124 pages – October 2010 draft (This is an early draft of the script. The situations, characters, and plot may change significantly by the time the film is released. This is not a definitive statement about the project, but rather an analysis of this unique draft as it pertains to the craft of screenwriting).

One thing I worried about after reading Buried was, “Will an audience be able to handle staying in a single enclosed space for the entirety of the movie?” The answer to that, of course, would depend on the director. So when I finally saw the film and spent 90 minutes in a coffin never once wishing we were cutting to an exterior location, I knew they picked the right guy. It’s probably not a surprise, then, that Cortes has found himself as one of the more in-demand young directors in Hollywood, evidenced by the sweet cast he’s secured for this project.

But then I found out Cortes would also be writing the movie. Directors, by their very nature, tend to put more emphasis on the visual than the written word. They’re thinking of crafting that perfect shot or that unique sequence nobody’s ever seen before, not rewriting the living hell out of a plot point until it sings on the page. There are exceptions of course (early Cameron Crowe, early James Cameron, Tarantino) but I always feel like we’re getting the short end of the writing stick when a director writes his own script, and although I love to be proven wrong, it usually doesn’t happen.

But hey, I was willing to give Red Lights a chance. The premise sounded cool and his debut American movie worked. So why not?

59 year old Dr. Margaret Matheson has dedicated her life to debunking psychics, those fakers who claim to have otherworldly powers, who are able to peek into the unseen dimensions that exist just outside our realm of consciousness. If you say you saw an alien, can talk to the dead, can read minds, can move objects with your brain, Matheson will calmly walk through your door and prove that you can’t.

She’s accompanied by 33 year old physicist Thomas Buckley, who has a little more faith in the supernatural than Margaret, but is quietly shocked as again and again Margaret is able to expose every “real” case they encounter.

While the two debunk cases including a haunted house (that turns out to be one of the daughters banging on the wall) and a faith healer (who’s being fed information about his victims through an earpiece), the most popular psychic in history, the blind Simon Silver, is gearing up for a comeback. The man used to be an iconic figure, one of the only popular psychics to have ever stood up to scientific scrutiny. When he books a series of shows, Thomas is eager to go after him. If they can prove that this guy is a fraud, they can basically prove that the whole field is a sham. But for whatever reason, Margaret refuses to mess with Silver. There’s something different about this one, something that doesn’t quite add up.

But when Silver finally agrees to allows his powers to be scrutinized by top level scientists to once and for prove he’s not a sham, Thomas will do anything to get on the committee, as he suspects Silver will try and manipulate the results. However when Silver gets wind of this man’s personal vendetta, he becomes fixated on him, and Thomas quickly realizes that he may be in over his head.

Red Lights is a funky little thriller that captivates you when it’s working and baffles you when it’s not. Imagine Fringe mixed with The Prestige and you have a pretty good idea of the script. I think the big problem here is that the story is weighed down by too many unneeded scenes, scenes that go on for too long, and scenes that are redundant. For example, you really only need one scene to establish your hero’s abilities – in this case the scene where she exposes the fake haunted house. But we also get two additional scenes reinforcing this ability. This would be fine if they pushed the plot forward in some way. But they do not. One of those scenes in particular, when they go to the preacher’s sermon, just goes on forever. It could’ve accomplished the same thing in half the time but refused to end. These are things pure screenwriters will endlessly work out until they get it right. But here, the mantra seems to be “more is more,” and as a result, it takes us a really long time to get to the plot.

In fact, I would say that the plot (take down Silver) isn’t revealed until halfway through the script . Complicating this is that it’s never entirely clear what the motivations of our main characters are for doing this. Margaret has an experience from her past that sort of explains why she’s so intent on exposing these people, but she doesn’t want to mess with Silver, so it’s not really applicable. Thomas, on the other hand, never explains why he needs to take down Silver so bad, which is problematic, since he eventually becomes the driving force behind the story. If we’re unclear on why our main character is doing what he’s doing, your story is in some trouble.

But all is not lost. What Red Lights loses in the structural department, it finds in the mood/tone department. The entire script is eerie, especially the character of Silver, who we’re constantly trying to figure out. It’s a nice little dance. Silver seems to not want to be exposed for something. Yet if he’s afraid of being exposed, how is he able to make all these otherworldly attacks on our heroes? That simple question drives our need to find out how this ends.

In fact, I would say Silver is the key to this screenplay working. Much like both characters in The Prestige or Edward Norton’s character in The Illusionist

, that central mystery of “How does he do it?” implores us to watch on. We want to know how Silver is pulling it off. So even though the story takes too long to get going, and gets bogged down in redundancy, the power of that question keeps us intrigued.

And really, this is what writing comes down to. How do you keep the audience’s interest? You should be able to randomly point to any page in your script and explain why, at that very moment, the audience will still be interested in what’s going on. Is it because you desperately want the character to achieve his goal (get the Ark in Indiana Jones), is it because you desperately want two people to be together (When Harry Met Sally

), or is it powerful mystery (Is Silver real or not?). That just might be enough for your script to work.

Do I have some issues with it? Sure, of course. Besides the issues I mentioned above, this is yet another script where there’s very little conflict going on in the central relationship (Margaret and Thomas). But Red Lights is a spooky script with an intriguing antagonist that has enough mystery and a unique enough story rhythm to keep you guessing til the end. I’d say it’s worth the read.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: When I see a script that’s this long (125 pages), the first thing I think is, I’ll bet anything there’s too much fat here. But I always ALWAYS allow the writer to prove me wrong. If I read that first act and the writer isn’t reintroducing his character three times, if he isn’t staying in scenes for 2-3 pages too long, if he’s not writing scenes that don’t push the story forward, if we get to the inciting incident early, I gladly tip my hat and say, “Okay, you proved me wrong.” But after reading hundreds of 125+ page screenplays, you know how many times that’s happened? Once. These huge page counts go hand in hand with these mistakes. I mean, do you really think it’s a coincidence that in a 125 page screenplay, the plot doesn’t emerge until page 60? So if you’re going to write a 125 page script, prove that you need all 125 of those pages! Don’t rewrite the same scene in a slightly different location ten pages later. Don’t write scenes that establish the same things about your character you’ve already told us. Don’t write scenes that aren’t pushing the story forward. You have to be sparse. You have to be diligent. You have to get to your story quickly. Cortes has a little bit of an excuse because he may be shooting stuff he knows he’s going to cut, but in the spec world, you don’t have that luxury.

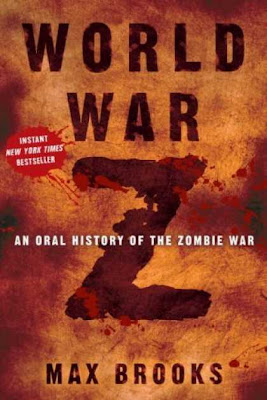

Genre: Zombie/Political

Premise: Five years after zombies nearly destroyed mankind, a government official is tasked with finding out the truth about how the zombie uprising started.

About: World War Z is based on the best-selling novel of the same name and is the unofficial sequel to the writer’s first book, The Zombie Survival Guide

. Brad Pitt’s Plan B Productions took on Leonardo DiCaprio’s Appian Way for film rights to the book, with Pitt snagging the rights in a high six figure deal. Marc Forster (The Kite Runner

, Stranger Than Fiction

, Quantum of Solace

) is tabbed to direct. This is a 2008 draft but apparently the project hasn’t been greenlit yet, as they’re still fine-tuning the script. Despite this patience, many people have told me how much they love this draft from Michael J. Straczynsky. Straczynsky has been writing forever, working on such TV shows as The Twilight Zone

, Jake and The Fatman

, Murder She Wrote

, and Babylon 5

. He broke through into the A-list writing group, however, after penning Clint Eastwood’s Anjelina Jolie-starrer “Changeling

.” He recently worked on the big Marvel tentpole pic, Thor.

Writer: Michael J. Straczynsky (based on the novel by Max Brooks)

Details: 118 pages – revised 3rd draft, April 23, 2008 (This is an early draft of the script. The situations, characters, and plot may change significantly by the time the film is released. This is not a definitive statement about the project, but rather an analysis of this unique draft as it pertains to the craft of screenwriting).

It’s fair to say I had absolutely no idea what I was walking into when I picked up World War Z. But ever since that Dead Island trailer hit, I’ve been in zombie mode, searching out anything and everything “zombie.” Then I remembered, probably the most recommended screenplay from e-mailers to me over the past year has been World War Z. I never picked it up because the title implied a generic ride. A bunch of zombies attacking the world. Uhhhh, isn’t that every zombie movie ever made? Little did I know that World War Z would be the single most original execution of a zombie premise I’d ever encountered. I mean this is truly a unique direction to take a zombie film in. The question, of course, is “How unique is too unique?” When do you stray so far from the appeal of a genre/concept that you’re no longer giving the audience what they want? That’s a question all of us face when trying something different, and it’s one that will determine the success of World War Z.

Government official Gerry Lane is being informed by one of his friends in the CIA to get the fuck out of Philadelphia. Like, now. The reason for the immediacy is the tens of thousands of zombies that are storming towards the city. Nobody knows how the situation got this bad this fast, but at this point, it’s everyone for themselves. So Gerry grabs his wife and two kids and hightails it into the country.

Typical zombie movie right? Now we watch as Gerry and other survivors stave off zombies, possibly in a remote town somewhere, ultimately succumbing to their doom?

Uhhhhh no. Not even close.

After succeeding in their escape, we flash-forward five years, to where the zombie threat has been neutralized. The world’s actually begun to reestablish some normalcy. That’s when Gerry gets a call from an old co-worker. They want to set up a small two-person committee to investigate how the zombie outbreak was able to happen. In short, a blame-game. It’s time to hold some people accountable for this mess.

So Gerry teams up with the no-nonsense Moria and they head off to China, where it’s believed that the outbreak began. But almost immediately, Gerry realizes the investigation isn’t on the up and up. The people they’re being booked with are low-level bureaucrats who know nothing. And even the big names they get to talk to aren’t spilling the beans. Strangely, Moira seems okay with this. And that’s when Gerry realizes this whole thing is a sham – a PR stunt meant to make it *look* like they did something. But there’s no desire here to tell the truth.

Well, if they wanted that kind of report, they shouldn’t have asked Gerry to write it. Gerry goes off the map, visiting and talking with people he shouldn’t be talking to, and begins to connect the dots to a shocking truth which proves that most countries, especially the U.S., knew how bad the zombie threat was and refused to do anything about it. But when Gerry finds the elusive recluse Radecker (spoiler), the man secretly in charge of devising a plan to save the world in case of a zombie attack, that’s when the real shit hits the fan, as it’s discovered just how many people were sacrificed to save others, all because a government was too damn lazy to deal with the problem when it was manageable.

During this time, the powers-that-be keep telling Gerry to ease up, implying that if he doesn’t, his family will stay stuck out in the unprotected zones. But Gerry pushes on til the bitter end, determined to find out what really happened, so the people who did this can be held accountable for their actions.

The great thing about World War Z is exactly what I hinted at at the beginning of the review. It’s different. It’s really different. In fact, you can’t believe you’re actually reading an international procedural about the investigation of the aftermath of a zombie apocalypse. That alone kept me turning the pages, because I just had no idea where it was all going. I say it to you guys all the time but here’s more proof of it. Find an angle to a genre that hasn’t been done before. Assuming the concept is solid and the execution is there, you’ve put yourself way above your competition because you’ve given readers something they rarely see – SOMETHING DIFFERENT.

At the same time, I can see why they’re having some problems with this one. The lack of any imminent danger for any of the major participants in the story, namely from…well…zombies, is probably having some studio execs scratching their heads. There’s a sequence of flashbacks during the script where we see Gerry and his family trying to survive during the apocalypse, which has some potential, but instead the scenes are used to explore a strange subplot with their sick daughter that doesn’t go anywhere.

Although I was enjoying the investigation, that question kept popping up in my head. “Where’s the danger?” While Gerry gets a few slaps on the wrist and some stern talking to, I never once felt like he was actually in danger for doing what he was doing. And that definitely needs to change. In particular, a lot more could have been done with the family. The threats coming from the U.S. are that his family won’t be let back into the safety zone if he keeps pushing. But if his family was safe enough for Gerry to leave them there in the first place, how much danger could they really be in? I thought they needed to do a lot more, like threaten the family’s life, so that Gerry would have to make a tough decision (this could have also led to the family going on the run in a zombie-infected countryside with the government chasing them – allowing zombie lovers to get their zombie fix).

Another issue I had was that the central relationship between the two investigators was boring. He and Moira had nothing going on between each other and therefore all of their discussions amounted to on-the-nose surface-level arguments about their duties as investigators. Obviously, Gerry has a family, so maybe you can’t create a relationship between the two. But what if they had a past? What if they had an affair or a one-night stand, anything so that one of the two wanted something the other didn’t (conflict). That would’ve made all their external decisions more interesting, since they would’ve conflicted with their internal feelings.

For example, I just watched the indie film “The Disappearance Of Alice Creed.” (Major spoilers ahead). In that film, the main character has a relationship with the girl they kidnapped *and* with his partner. He, of course, is keeping this secret from both. So when his partner says they’re going to leave the girl in an abandoned warehouse, where she might die if they’re unable to come back, that decision is extremely complicated for him. He must act as if he doesn’t give a shit, while at the same time working out how he’s going to save his girlfriend if things do, in fact, go wrong. That’s the kind of shit you want to be putting your characters through. Have their external decisions conflict with their internal decisions. I thought World War Z could’ve created a more interesting dynamic between Gerry and Moira if they’d played with the relationship more.

But in the end, this script won me over because despite the lack of conflict between the investigators, I found myself sympathizing with and admiring Gerry’s plight. It’s said that World War Z may be based on the Hurricane Katrina response, and much like we wanted people to be held accountable in that situation (and in 9/11, and in the mortgage crisis), we have that same feeling here. Nobody likes when a government takes advantage of its people, and so there’s a natural instinct to see justice served. And the mystery into the zombie uprising itself – while no Chinatown – was still pretty damn interesting. For that reason, World War Z is definitely worth the read.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Are you exploring your central relationship to its fullest potential? Whenever you pair two people up for an entire movie, you want to create some sort of interesting dynamic between them. The resulting conflict is what fuels the audience’s interest to watch them then for the next two hours. In a comedy, it might be as simple as them hating each other (Rush Hour). In a romance, it might be an obstacle keeping them apart (The Notebook

– she’s getting married to another man). In a boxing movie, it might be your brother/trainer sabotaging your career with his drug problem (The Fighter

). You want to create as interesting a dynamic as possible between the two leads because ultimately your movie is going to live or die on that relationship. Despite Seven having some wonderfully memorable sequences

, I think something that really kept it from reaching true classic level was that the relationship between Pitt and Freeman’s character had so little going on in it.

Genre: Comedy

Premise: 24 year old Ronnie Epstein wakes up after a night of drinking to learn he drunk dialed 200 people. He’ll spend the next 24 hours dealing with the consequences.

About: Drunk Dialing was one of the ten finalists for the 2010 Nicholl Screenwriting Competition.

Writer: Sebastian Davis

Details: 101 pages – 4/08/10 draft (This is an early draft of the script. The situations, characters, and plot may change significantly by the time the film is released. This is not a definitive statement about the project, but rather an analysis of this unique draft as it pertains to the craft of screenwriting).

I’ve seen a few of these “dunk dial” premises floating around over the last couple of years and I’m not surprised why. It’s a great premise for a comedy. I mean who hasn’t woken up after a night of exceeding their adult beverage limit, only to find they’ve sent out ill-advised e-mails or made ill-advised calls to the last people they should’ve made them to? I’m still dealing with the consequences from a night five years ago where my friend somehow managed to mass text “I miss you,” to all 500 contacts on my phone. Old girlfriends, work contacts, friendships that had fallen by the wayside…I even had the number of one of my clients’ ten year old son on my phone for some reason. Boy did I have some explaining to do after that one.

But the question remains the same as it always does with these funny premises. What about the execution? Is Drunk Dialing the perfect connection? Or is it a dropped call?

24 year old Ronnie Epstein has just woken up in Tokyo. Now THAT’S what I call a night. To make matters worse, he checks his phone and realizes he made 200 calls last night! Calls to his boss, calls to his old girlfriend, calls to people he hasn’t seen in years. This is ugly. But before he can enact Operation Damage Control, the third strike hits – a petty thief steals his phone!

As Ronnie stumbles outside, he realizes he’s not in Tokyo, but rather Little Tokyo in LA. Before he can process that thought, Mary-Lou Whitman, a hot chica in a pink corvette and a girl Ronnie spent one night with five years ago, screeches to a halt in front of him. He called her needing help last night and, voila, here she is.

Mary-Lou explains to Ronnie that he changed her life when, after making love five years ago, he told her that she should do this kind of thing as a profession. So she followed his lead and is now a porn star! In fact, they’re going to the set of her latest porn film right now.

In the meantime, we flashback to 3 years earlier when Ronnie was a college student/street artist. Back then he had the hottest girl, DJ Keoko, by his side, and the two spent every second partying and living it up. But when it was time for Keoko to pursue a job in another country, Ronnie chose to let her go and stay in LA. This fateful decision led to a series of safe choices, culminating in him becoming a floor mat salesman.

Anyway, we jump back to the present where Ronnie’s old friends keep popping up out of nowhere, responding to Ronnie’s drunk dials from the night before. They include Marcus, an ibanker who drained the bank accounts of some angry Wall Street investors, and an Irish drug dealer, whose questionable dealing habits have him mixed up with the Irish mob. And then, of course, there’s Keoko, who keeps asking Ronnie if he meant what he said on her voice mail last night, a question Ronnie can’t answer because he doesn’t remember what he said.

Naturally, Ronnie will have to save his job, ditch his clingy new/old friends, and get the girl, all before the day is done. Can he do it? Or has he drunk dialed his way into oblivion?

Drunk Dialing was a tough script to get a handle on. While I was reading it, I wasn’t sure if we were exploring the most interesting version of the story. In particular, the flashbacks to college seemed to intrude on the pace and rhythm of the script, giving what should have been a straightforward operation a herky-jerky unsure-of-itself feel.

Flashbacks are dangerous. It’s just so hard to get them right. And when you think about it, unless we’re talking about a well-crafted Oscar-bound mystery film from Argentina, audiences are usually interested in what’s happening *right now,* not a week ago or a year ago or five years ago. They want to see our hero encounter problems this minute, because those are the problems that are affecting his immediate goal – not what happened back in 2008. Now, of course, the past can shed light on your character, giving us a better understanding of them, but most of the time, all that work and page space you put into those flashbacks can easily be handled by a quick present day exposition scene.

On the plus side, if you like “24 hour crazy fucking night/day” comedies, Drunk Dialing is for you. Our hero is running all over the place, staving away various lunatics he drunk-dialed the night before, and doing so with characters we haven’t seen in these types of films before (I can’t remember ever seeing I-bankers or the Irish Mob in this kind of movie). The comedy’s really broad, so you’re either going to love it or hate it, but there are definitely some funny moments.

Besides the flashback choice, the structure’s pretty solid. We establish that our hero’s in line for a promotion, creating stakes for the main character. Our character has a passion he’d rather pursue (street art), which means he has some inner conflict he’s trying to resolve during the film. He’s got a girl he’s trying to get back – yet another goal that’s pushing him and the story forward. And the script has a very young hip feel, almost like Scott Pilgrim, but easier to digest. I can see a bunch of high school and college kids wanting to check this out.

But here’s the thing. Of all the genres I read, comedies are the sloppiest of the lot by far. And I guess it makes sense. Writers think, “It’s a comedy. Who cares about making the story perfect?” As a result, I end up reading all these comedies with tremendous potential, but that never make it to the finish line. It’s like the writers stop at the 17k mark and say, “That’s probably good enough.” It’s rare that I see a writer try to craft a comedy with the same attention to detail that they might craft, say, a drama. That’s why it’s so rare to find a great comedy spec. Cause the writers are only giving you 60-70%.

And while Drunk Dialing makes it closer to the finish line than most, it still feels like one of those comedies that bowed out before finishing the race. The pieces don’t quite fit into a whole. I don’t feel like the script has been reworked and reworked into the best possible version of itself. It’s basically a string of funny set-pieces. Maybe the past stuff was an attempt to create something more meaningful, but it’s not fleshed out enough in its current form. It needs more work.

But hey, you know my standards are impossibly high for comedies. What did you guys think?

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Having one of your leads move/leave/fly to another state/country at the end of your movie is one of the easiest ways to create a ticking time bomb. For that reason, it’s a great device to use. But you can’t use the “race to the airport” scene at the end of a movie anymore. You just can’t do it. It’s become a cliché within a cliche and if you put it in your screenplay, 80% of the people who read it are going to groan. Be creative. Look for other ways to write the climax. I read a script not long ago where a guy was going to the airport to stop his girlfriend from leaving but his car broke down. He realized he could still catch her at her place. So the final scene is him running through the suburbs trying to catch her before she gets in the cab, rather than running through an airport. It’s a small change but it’s different from what we’re used to seeing, so it works. Always avoid cliché choices, particularly at the end of your screenplay.

Here we are, only three days away from the 2011 Academy Awards. I’m so excited! Yeah, I know, I know. The Oscars are worthless. It’s a popularity and “Who You know” Contest. Blah blah blah. But every time I begin to think that way, I look at the candidates, and you know what? They’re pretty damn accurate most of the time. I mean look at the Best Picture Category. Are there any movies that didn’t make the cut that you think should have? Well, actually, there is. But I’ll get to that in a second.

Anyway, I got some bad news. I’m not going to be live-blogging on Sunday. It’s not cause I don’t love you guys. It’s because live-blogging is hard! Last year they kept screwing up the presentation order, forcing me to write out my prediction and thoughts for each category within five seconds, post each thought, then post an opinion thought after the result. Inevitably something would go wrong and I would have to go back and clean it up, all while the next category was starting, forcing me to simul-post. And let me tell you, I’m not good with simul-posting. I mean come on. Aren’t these Oscar producers thinking of the hard work and dedication bloggers everywhere are putting into this?

For that reason, you’re going to be getting my predictions in all the big categories right here and now. Naturally, all I really care about is the screenwriting competition, but I have some pretty strong opinions on these other categories as well. There’s something about the acting and directing categories in particular that bring out the nasty in me. People who’ve endured my past thoughts on Matt Damon and George Clooney know this well. Anyway, let’s dig in here. Feel free to leave your own pick in the comments section. I know I’ll be coming back here Sunday night to celebrate my 8 for 8 victory.

BEST PICTURE

Black Swan

The Fighter

Inception

The Kids are All Right

The King’s Speech

**The Social Network**

127 Hours

Toy Story 3

True Grit

Winter’s Bone

To me, Inception and Black Swan are the most cinematic experiences of all these ten movies. But the name of this category is not “most cinematic.” It’s “Best Picture.” Toy Story 3 is probably the most complete movie in this group from top to bottom. It’s got the best story. It’s got the best characters. It creates the strongest connection between itself and the audience and has the fewest flaws. Buuuuuut…it’s a cartoon and something wouldn’t feel right about a cartoon winning this category. The King’s Speech has really come on late in this race and is a great “1a” choice. It would be my personal pick for Best Picture. But when it’s all said and done, The Social Network has the most buzz, and probably the most money, behind it. You can already smell the victory. But before I leave this category, I’m still trying to figure out all the love for The Fighter. I thought the movie was okay but I mean, come on, isn’t it just an excuse for Christian Bale to let out all that repressed energy he had to hold back during the Batman films and win himself an Oscar? Here’s why this movie fails for me though. I keep comparing Mark Wahlberg to Sylvester Stallone in Rocky on the charisma scale. Wahlberg’s a solid 3 and Stallone’s a 10. I just didn’t care if he won that fight at the end or not. Oh, and the one tragedy here is WHERE IS THE TOWN!?? That should’ve gotten in over The Fighter, Inception, 127 Hours and Winter’s Bone easily. Grrrrr. Bad Academy! Anyway, Social Network for the win!

PERFORMANCE BY AN ACTRESS IN A LEADING ROLE

Annette Bening (The Kids are All Right)

Nicole Kidman (Rabbit Hole)

Jennifer Lawrence (Winter’s Bone)

**Natalie Portman (Black Swan)**

Michelle Williams (Blue Valentine)

I don’t have a chicken in this fight but I do have a…swan. Heh heh. Get it? No? Okay, I’m saying I’m picking Natalie Portman to win. That movie is so haunting and it’s the best job Portman’s done in forever. It almost makes me forget Queen Amidala. Almost. I’m still trying to wrap my head around the inclusion of Miss Boring Face from Winter’s Bone though. Is there a single moment in that performance where you think, “Wow, great acting?” And while I loved The Kids Are All Right, I’m not sure Annette Bening had much to do either. She was fun. But it’s not an academy award performance.

PERFORMANCE BY AN ACTOR IN A LEADING ROLE

Javier Bardem (Biutiful)

Jesse Eisenberg (The Social Network)

**Colin Firth (The King’s Speech)**

James Franco (127 Hours)

Jeff Bridges (True Grit)

Whaaaat? Jesse Eisenberg for best actor? He acted like an asshole for two hours! I would’ve nominated his turn in Zombieland over this. Javier Bardem’s film is flying way too under the radar for him to win anything. That leaves Firth, Franco, and Bridges. Bridges won last year

so he’s not winning twice in a row. And Franco can’t hang with these actors. So Firth takes the prize. That was easy.

PERFORMANCE BY AN ACTOR IN A SUPPORTING ROLE

**Christian Bale (The Fighter)**

John Hawkes (Winter’s Bone)

Jeremy Renner (The Town)

Mark Ruffalo (The Kids are All Right)

Geoffrey Rush (The King’s Speech)

This is always the best race since supporting roles don’t need to anchor the movie and therefore tend to be the flashiest. While I thought The Fighter was pretty average, Bale definitely did something unique with his part. Having said that, I really liked Renner in The Town. When he looked into people’s eyes? I honestly believed he could kill them. John Hawkes gets a nomination for grabbing a 17 year old’s hair. Ruffalo’s role doesn’t have enough sizzle factor. And Rush is good but for some reason isn’t getting a lot of mileage from this role. I want Renner to win but Bale’s got this locked up.

PERFORMANCE BY AN ACTRESS IN A SUPPORTING ROLE

Amy Adams (The Fighter)

Helena Bonham Carter (The King’s Speech)

**Melissa Leo (The Fighter)**

Hailee Steinfeld (True Grit)

Jacki Weaver (Animal Kingdom)

Say what you will about David O. Russel. I’m not sure he even knows what the word “narrative” means. But the guy always gets some unique performances out of his actors. So I’m leaning towards the two people he directed in this category, Adams and Melissa Leo. I know Hailee Steinfeld is the new young “it” girl, but I’m not buying it. The dark horse here is Jacki Weaver. I thought she was really good. But that movie’s so small. I don’t think enough Academy members have seen it. Three months later and I’m still remembering Melissa Leo’s performance from The Fighter, so I’m taking an underdog shot with this one and going with her.

ACHIEVEMENT IN DIRECTING

**Darren Aronofsky (Black Swan)**

David O. Russell (The Fighter)

Tom Hooper (The King’s Speech)

David Fincher (The Social Network)

Joel and Ethan Coen (True Grit)

This is a GREAT category. You have some real monsters in this group. But I think we can kick Russell and Hooper out easily. That leaves us with visionary titans Aronofsky, Fincher, and the Coens. You know, I still don’t know what people base the criteria of best director on. Is it for the overall vision? Is it for the amazing performances? It seems to me that the best directing decisions probably happen in the heat of the battle behind closed doors. But I think it’s safe to say Fincher isn’t stretching his muscles here. And out of the remaining competitors, Aronofsky is taking way more chances and way more of those chances are paying off. So I’m saying Aronofsky for the win, a win he rightly deserves.

ADAPTED SCREENPLAY

127 Hours (Simon Beaufoy and Danny Boyle)

**The Social Network (Aaron Sorkin)**

Toy Story 3 (Michael Arndt, story by John Lasseter, Andrew Stanton and Lee Unkrich)

True Grit (Joel Coen and Ethan Coen)

Winter’s Bone (Debra Granik and Anne Rossellini)

There’s about as much suspense in this category as there was in the movie, Blue Valentine. I never saw 127 Hours as a strong screenplay and find it odd that it was nominated. Like I said back in my review, it’s a film way more than a script. Toy Story 3 is great and all but it does suffer a little from not being fresh. True Grit’s alright but nothing special. Winter’s Bone…I mean, this just seems like a lazy pick to me. A very standard story. Very sparse. I don’t know what it is about the screenplay that would get anyone excited. That leaves, of course, our clear cut runaway winner, the best reading experience I had of 2009, The Social Network. A-duh.

ORIGINAL SCREENPLAY

Another Year (Mike Leigh)

The Fighter (Paul Attanasio, Lewis Colich, Eric Johnson, Scott Silverand Paul Tamasy)

Inception (Christopher Nolan)

The Kids are All Right (Stuart Blumberg and Lisa Cholodenko)

**The King’s Speech (David Seidler)**

This is a really interesting category. Inception must be in here for imagination, because it violates so many good screenwriting principals and is so lazy in its storytelling practices that it’s hard to argue for its inclusion. The Fighter is just a complete mess on the page, often confused about which character’s story it wants to tell, and concludes its turbulent 120 pages with a last second fight we’re all of a sudden supposed to care about. Can you imagine if Rocky would’ve found out he was fighting Apollo Creed 20 minutes before the end of the movie?? Okay okay! I’ll stop ragging on The Fighter. Of all the films in the two screenplay categories, Mike Leigh’s is the only one I haven’t seen or read, so if that script is brilliant, my apologies for missing it. The two best scripts on this list by far are The Kids Are All Right (old review here) and The King’s Speech (old review here). Personally, I love both of these scripts. And because there’s more to juggle, I believe The Kids Are All Right is the better script, but The King’s Speech is the one that makes you feel better inside after it’s over, and for that reason, that’s my pick. And how awesome would it be to have a 76 year old screenwriter win the Oscar!!

I’ll be reposting this on Sunday to keep the debate going. Oh, and for anyone who’s interested, here’s a link to all 10 of the Oscar nominated screenplays.