It’s not often that I really take a script to town. After reading as many scripts as I have, I have way too much respect for writers to tear down their babies just cause it makes for a good review. However, every once in awhile, I let a script have it. Enter M. Night! Sure, this is an older script, and one that’s already been reviewed on the site by another reviewer, but my buddy Colin over at Take 148 has been doing an M. Night review marathon and wanted me to finish it off for him. So head on over there and check out my review for “Labour Of Love.”

Genre: Crime Drama

Premise: (from IMDB) A newly-released ex-con seeks revenge upon his mentor who framed him for a crime he didn’t commit.

About: I said I had an Oscar winning screenwriter this week but I just remembered Up in the Air lost out to Precious at the Oscars, so I guess I don’t. Still, the co-writer of Up In The Air is easily one of the hottest scribes in town, having over 15 projects in development. That’s a nice bump for a guy who just a year ago had only two produced credits to his name, “The Longest Yard,” and “Texas Chainsaw Massacre: The Beginning.” Turner’s used his newfound buzz to not only get this latest script sold but attach himself as director. The project’s been getting a ton of heat and is said to have Eric Bana and Collin Farrell attached. Turner doesn’t believe in screenwriting books or seminars (“If you’re being taught the same skills as [everyone else], then what’s the point? Find your own answers,” he says.) However, he’s a huge reader, still reading a screenplay a day. As a young screenwriter, Turner wrote a dozen screenplays before sending any of them out.

Writer: Sheldon Turner

Details: 117 pages – January 9, 2010 draft (This is an early draft of the script. The situations, characters, and plot may change significantly by the time the film is released. This is not a definitive statement about the project, but rather an analysis of this unique draft as it pertains to the craft of screenwriting).

I have to admit, I struggle to enjoy any movie in this genre.

So why am I reviewing this script? Because people have been knocking down my e-mail door ever since the project was announced begging me to review it. There are so many people fascinated with cops, fascinated with the FBI. I don’t know why but all these movies tend to blend into each other for me. Just like I was saying in my review of Drive, in order to get my attention with one of these movies, you have to do something really different, and while By Virtue Fall takes some interesting chances, they weren’t enough to sway me from my usual reaction to these kinds of films.

The story centers around two federal agents. The first is Matthew Vanetti. He’s the Golden Boy, the one with the bright future, the one who does everything by the book. Matt’s partner and good friend is Danny Sloan. Danny is a drunk, a fuck-up, a corrupt agent who can be bought with a hot cup of coffee and a jar of applesauce. The two live on opposite ends of the spectrum, with Matthew ready to marry his soul mate and Danny barely able to keep his marriage together.

Unbeknownst to Matt, Danny is selling federally confiscated firearms to the big badass in town, Jericho Trower. Somehow – though I still don’t know if Danny does it on purpose or not – the feds find out and think Matt is responsible for dealing the guns to Jericho, not Danny. As a result, Matt gets sent off to jail for five years, losing his job, his reputation, and even his girlfriend, who apparently only loves him until he’s behind bars.

The story then follows both characters in their respective positions. The former Golden Boy slowly descending into prison life, shaving his head, blanketing himself with tats, pumping himself up, while Danny the alcoholic stumbles into a series of lucky breaks and begins ascending the Federal ranks, getting back together with his wife, and becoming a big shot at the agency.

But Danny can’t shake what he did to his best friend and partner, and has a hard time sleeping at night. He knows that if Matt ever found out the truth, he would come after him in a second. Indeed, Matt is like a caged animal waiting to be let loose. He holds everyone accountable for the deceit that put him here, and when he gets out, he’s going to make them all pay.

Besides the subject matter not being my cup of tea, my big issue with By Virtue Fall is the thin plot. There’s no inherent goal driving the story here. We’re simply watching two people’s lives laid out in front of us and while I enjoyed the ironic turns for both, it was really hard to stay interested when neither of the characters were pursuing anything.

I suppose our interest is driven by seeing what Matt’s going to do to Danny and the others once he gets out, but I had trouble getting excited even for that. I mean, it’s not like Danny killed Matt’s wife and framed him for it. It’s a gun-selling charge. In the grand scheme of motivation, it never seemed like that big of a deal to me. I understand that if he was framed for something like murder that he’d be stuck in jail for a lot longer than five years, which would’ve upset the timeline, but it would’ve infused the character with a lot more motivation. It may have even opened up some new story possibilities. Matt’s framed for killing someone close to him. He gets a 50 year sentence. The only way to get revenge on the people who killed his [wife/son/whoever] is to break out. This would’ve added a lot of drive to the story. If Matt’s planning an escape, it makes him more active, which makes him more interesting, which gives the story more momentum, and that goal I was looking for.

That’s not to say there’s nothing to see here. I have a feeling that fans of The Departed (another script I felt had little driving the story) are going to like this quite a bit. It’s fun to watch the transformation of these men, especially Matt, who becomes a completely different person. And while there’s no clear character goal, I think Turner would argue that our desire to see these two finally square off in the end is what’s driving our interest. Indeed, he may have a point, and since I’m far from an expert on this genre, I’m not going to argue that.

You know one of the things I think I learned while reading this is that crime scripts have the unfortunate handicap of not reading well. There are always a lot of characters – a lot of people to keep track of – and there are usually a lot of double-crosses or intricate character interactions that occur as the script goes on. Onscreen, when you can see the characters’ faces, it’s easy to remember who’s who. But on the page, it can be really tough, so you’re always rereading things and going back in the script to confirm that what you think is happening is really happening. This happens every time I read one of these scripts, which may explain why I rarely like them.

I wanted to enjoy this. I like Sheldon Turner’s writing style. It’s just for me personally, I wish there was more plot pushing the story.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: One thing I’ll give credit to Turner for – he knows how to get big actors attached to his project. One of the things I’m paying more attention to these days is not just how to sell a script, but how to GET A MOVIE MADE. The quickest way to do that, obviously, is to write a part (or parts) that big actors want to play. A or B list attachments mean go-pictures and I think that’s what separates a lot of the top professionals from the rest of the pack. While story-wise, this script is light, it definitely has two characters that actors would want to play. Why? Well, the transformations of course. You have one character who’s a clean-cut do-gooder who transforms into a tattooed juice-head killer. And the other is a stumbling drunk who turns into a successful star for the government. Actors love shit like this, getting to play both ends of the spectrum, because it stretches their acting muscles. So I’m not surprised Farrell and Bana signed onto this.

Genre: Heist/Mystery/Comedy

Premise: Two sets of criminals try to rob a bank at the same time.

About: The follow-up script from the writers of The Hangover. The movie will star Patrick Dempsey, Ashley Judd, Pruitt Taylor Vince, Jeffrey Tambor, and even Mekhi Phifer, who I guess we can confirm from this casting still acts. Lucas and Moore are high-concept specialists, also penning big spec sellers “Ghosts of Girlfriends Past” and “Four Christmases.” The two had little success writing alone and bumped into each other while working for the producer of Beverly Hills Cop. After awhile they became the go-to guys for punching up scripts, working on properties such as “Wedding Crashers,” “27 Dresses,” “Chicken Little” and “Mr. Woodcock.”

Writers: Jon Lucas & Scott Moore

Details: 113 pages – Jan. 10, 2010 draft (This is an early draft of the script. The situations, characters, and plot may change significantly by the time of the film’s release. This is especially true with comedies. So this is not a definitive statement about the project, but rather an analysis of this unique draft as it pertains to the craft of screenwriting).

Okay so I think I’ve made it clear on the site that The Hangover is the template you should be using to write your own comedy spec. Not the idea itself obviously (there’s enough stealing in Hollywood) but the approach. It’s an original concept. It fulfills the promise of the premise. It’s got a strong goal. The execution is perfect. It’s lean. It’s funny. It’s different. It has great characters. Etc. Etc. It pretty much does everything you wanna do in a spec. So I, like many others, have been waiting to see what the writers, Jon Lucas and Scott Moore, would follow it up with. That script is here, in the form of the bank heist comedy, “Flypaper.”

I’m trying to find a base point here while reviewing Flypaper, but the truth is, I’ve never read anything quite like it. This is a comedy, a heist film, a whodunit. It’s its own thing. That’s clearly its biggest strength – the script is original. The question is, in trying to be so many things, does it end up not being anything? Good question. And the answer may not be a happy one.

Tripp Kennedy, an “accidentally handsome” drifter who moonlights as a pickpocket, isn’t able to keep a job for very long. That’s because he has a super-intense version of ADD that severely affects his concentration. On this particular day, we watch him stroll into a bank and start hitting on Kaitlin, a gorgeous teller who’s about to marry an extremely rich man. Tripp senses there’s a disconnect in this relationship however, and pokes around for a potential way in.

The flirting is cut short when a group of men posing as construction workers whip out their guns and tell everybody they’re robbing the place. Except that this happens at the EXACT SAME TIME as two other men (low-rent hustlers who we’ll get to know as “Peanut Butter and Jelly”) whip out THEIR guns and tell everybody THEY’RE robbing the place. What? Two sets of criminals robbing the same bank at the same time??

After some initial arguments between the bad guys about who was here first, Tripp comes forward and suggests that they both rob the same bank. The big-timers can go rob the vault and Peanut Butter and Jelly can go rob the ATM machines. Everybody leaves happy.

In the meantime all the hostages are stashed in a back room, including Tripp and Kaitlin, and proceed to argue about what the best way to handle the situation is. Should they try and escape? Should they just wait til the bad guys are finished? Well it turns out the bad guys aren’t the only people they have to worry about. That’s because our hostages start finding their cohorts murdered and stashed inside concealed places. One by one, the hostages are being offed, creating a triumvirate of chaos. Smart criminals, dumb criminals, and a homicidal maniac killer! Tripp, fashioning himself a modern day Sherlock Holmes, attempts to piece together the clues to out the killer before he or Kaitlyn become a victim.

Okay, so, where do we begin with this one? I wasn’t feeling it. The concept itself is pretty neat. Two sets of criminals try to rob the same bank at the same time. At first glance you’re thinking that could be funny. However, after that awesome opening – when both robbers announce their plans at the same time – you realize that that’s pretty much the highlight of the story. How do you keep the premise funny after that?

I think Lucas and Moore realized this so they tried to come up with a way to keep things moving for the next 100 minutes. This, obviously, is where the “killer within the bank” scenario came up. Here’s the problem with that aspect though: It feels like a completely different movie. The reason it feels like a completely different movie is because you don’t need the “dual-robbing premise” to execute it. You could just as easily have done this with only a single group bank robbery. For that reason, the two plots begin competing against each other, and the script never quite figures out which one is in charge.

This gets to the heart of my problem with the script. It’s never taking advantage of its premise. Everything that happens – all the comedy, all the story – has little or nothing to do with two sets of bank robbers trying to rob the same bank at the same time. I mean sure the two groups get into scuffles every once in awhile, but I wouldn’t call that cleverly exploiting the premise.

Tripp, likewise, is a character with problems that have nothing to do with the situation. He has mega-ADD. Okay, that’s an interesting character flaw, but how does ADD in any way play into a story about solving a dual-bank robbing heist? It doesn’t, which makes the flaw seem fancy and a fun character quirk, but ultimately empty. Look at Knocked Up for comparison. Seth Rogan’s character flaw, that he’s lazy and irresponsible, plays directly into the premise, because lazy and irresponsible are the worst things you could be if you were going to raise a baby.

There are some logistical problems as well. Nobody keeps an eye on the hostages and they’re apparently able to run around willy-nilly through the bank, which kept bringing up the question, why didn’t they just walk out the door and leave? I’m sure there was a reason for this – maybe the doors were locked or something – but because they had so much freedom, it just felt like they could do whatever they wanted, and that made their dire situation feel decidedly un-dire.

As is always the case with comedies, the humor here will make some people laugh and others cry. A big portion of the jokes are heaped on the criminals being obsessed over an online ranking system for bank robbers, to the point where every robber here is more concerned with upping their online ranking than actually stealing money. I know this is a comedy but we’re having trouble believing that this hesit means anything to anyone as it is. Robbers gunning for online rankings made the pursuit seem almost like a joke.

I must admit, however, that I loved when each set of robbers picked hostage “teams” like they were on a playground. This is exactly the kind of stuff I was looking for more of – comedy that stemmed directly from the premise. But this is the only joke I remember that did that.

Flypaper is the equivalent of trying to pack a honeymoon’s worth of clothes into a carry-on bag. There’s just too much going on. The competing storylines confuse the audience, the comedy doesn’t take advantage of its premise, and the stakes aren’t high enough for the robbers. My hope is that they have a specific vision based off of all the broad comedy here that somehow comes together when it hits the screen. Maybe they even cut out one of the competing storylines in the final draft. I hope it gets fixed cause I like Moore and Lucas as writers. I think the high concept comedy is struggling and these two are a couple of the only guys who still get it. This draft just wasn’t doing it for me.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: A good way to create a comedic protagonist is to look at your concept and ask, “Who’s the worst person I could put in this situation?” So for Knocked Up, which is about responsibility, your main character is going to be extremely irresponsible (an unemployed loser). For Liar Liar, which is about truth, your main character is going to be a habitual liar (a lawyer). For Happy Gilmore, about the upper crust overly polite game of golf, your main character is going to be a loud-mouthed dickhead who hates the sport more than anything. That’s something I wanted to see with Tripp in Flypaper.

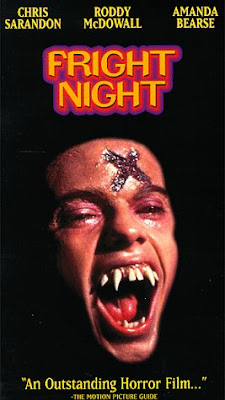

How did anyone survive without Scriptshadow on Monday? I think one guy wrote in from Germany saying he was going to kill himself cause I didn’t post a review. Or maybe he said he was going to kill me. Either way, I’m sorry but I really needed a break. I’ll try to make it up to you this week with a script from a very high profile comedy writing team and another script from an Oscar winner. Requests for the latter script have been flooding my inbox for weeks. I’m tempted to tell you how it went right now but what fun would that be? Heh heh heh. Roger Balfour isn’t going to make you wait though. Here he is with a review of Fright Night.

Genre: Horror

Premise: When a teenager learns that his next door neighbor is a vampire, no one will believe him.

About: Craig Gillespie is helming this modern retelling of this 1985 horror theater classic, that was written and directed by Tom Holland and starred Chris Sarandon, William Ragsdale and Roddy McDowall. Marti Noxon (Buffy, Angel, Grey’s Anatomy, Mad Men) has retweaked the story for a new generation. Leading the cast is Colin Farrell, Anton Yelchin, Christopher Mintz-Plasse, Toni Collette and David Tennant.

Writer: Marti Noxon

I remember watching repeats of the original Fright Night on the local tv station, which is probably the perfect way to watch a vampire movie that plays as a sort of paean to the genre with its Horror Movie-obsessed protagonist and his Horror TV Host mentor. I re-watch it every October, as it’s perfect for Halloween not just because it’s a scary movie, but because it’s nostalgic. There’s a spirit in the story and performances that harkens back to Dark Shadows, Drive-In Creature Features and Christopher Lee Hammer Horror flicks. Just the perfect movie to watch on a cold autumn night when the neighborhood is decorated with jack-o-lanterns, skeletons and fake cobwebs.

[ ] wasn’t for me

[xx] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Teaser prologue. If you’re writing a horror story, whether it be a monster movie or a ghost story, it’s usually wise to kick things off with a quick teaser that hints at the menace your story will be about. In Fright Night, there’s a three page sequence that’s about a teenager trying to survive a deadly and mysterious attack on his suburban family by an unseen threat. We see glimpses of something tearing apart bodies. We see glimpses of something…not human. Your first act will be all about establishing your setting, characters, world and story. These things usually are a slow-build up, so it’s smart to kick things off with a short sequence that shows your monsters or ghosts without showing your monsters or ghosts. Build a tense scene showing something horrible happening at the hands (or fangs) of your menace, but don’t give it all away. Create mystery, move along to your story, then when it’s right, show your creature, monster or ghost in all their creepy glory.

Sad news. We’ll be taking Monday off. You see, here in the states, we have something called “Labor Day,” which celebrates Americans working by, um, not making them work. I wholeheartedly endorse this decision and will show my support by not working either. So go catch up on some reading and we’ll be back Tuesday with something to talk about. Enjoy the holiday!