Search Results for: F word

Many years ago I went to one of those Screenwriting Expos.

I think that’s what it was called, actually – “The Screenwriting Expo.”

This was back in the day when the word “e-mail” was as buzzy as saying “TikTok.” “You’ve got mail” was as addictive a sound as the “ding” you hear when you get a new text. It was the original dopamine hit. In other words, it was a simpler time. And a world where the only screenwriting information you could get was from books and expos. So I was excited to be there.

However, the more I walked around the place, the more I realized it was nothing more than a giant excuse for bottom feeder industry types to hawk their wares and get you to sign up for classes or mentorships or newsletters you didn’t want to sign up for. I went from top of the world to ‘lost all faith in humanity’ in 60 minutes.

However, there was one teacher from the Expo I still remember. I don’t remember his name (for the purposes of this article, I’ll call him Jason). But what I do remember is that he was passionate, a stark contrast to the 200 other tricksters who leered at everyone as if they were giant walking wallets.

After everyone who’d signed up for the class arrived, Jason popped in a DVD of “Stand By Me,” and proceeded to pause it every so often to explain the screenwriting mechanisms that were going on underneath the surface.

It was instructional, effective, and fun, due to his outsized passion for the movie. I mean, I dug Stand By Me. But this guy really REALLY liked Stand By Me.

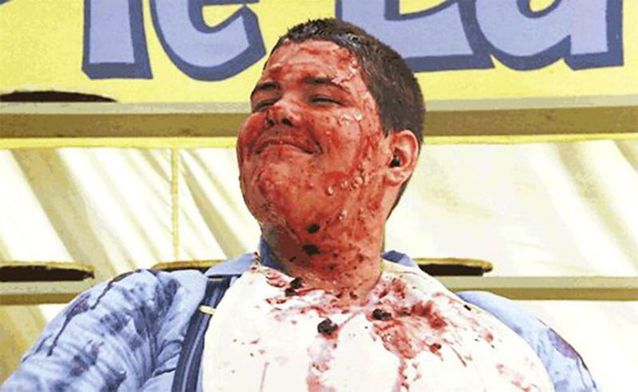

The part that he liked the most still sticks with me to this day. Jason went bonkers over Gordie’s midpoint story to his friends about a pie-eating contest. If you haven’t seen the film or don’t remember it, it’s about four 12-year-old friends who travel across the state to see a rumored dead body in the woods.

The scene in question occurs as the friends are taking a break and they ask Gordie (this is based on a Stephen King story so, of course, there has to be one writer in the mix) to tell them a story. We then cut out of the kids story and for EIGHT ENTIRE MINUTES we get a story THAT HAS NOTHING TO DO WITH ANYTHING ELSE IN THE MOVIE. I capitalize that because that’s what this teacher kept emphasizing.

“EIGHT MINUTES! EIGHT MINUTES THE STORY WENT ON! AND IT HAD NOTHING TO DO WITH ANYTHING ELSE IN THE MOVIE!”

The story Gordie tells is funny. It’s about an overweight kid who enters a pie-eating contest and the experience is so overwhelming that, at the end of it, he throws up. That leads to the other contestants throwing up. Which then leads to the audience throwing up. Soon everybody is throwing up.

Jason kept hitting on the fact that you just “don’t do this.” You don’t stop your movie for eight minutes to introduce brand new characters and a brand new story that has nothing to do with anything else in the movie. If these characters were related to our heroes, you could justify it. If these characters somehow came back into the story later on, you could justify it. But none of that happens. It’s its own self-contained movie within a movie.

Jason was so obsessed with this little scene that, over the years, I’d find myself recalling the famed sequence and wondering why he’d gotten so worked up about it. His point seemed to be contradictory. He both loved the scene but was baffled that they’d included it. I couldn’t resolve what his message was.

Flash-forward to 2020. I’m reading a script just a few days ago from a very talented writer. He’d written a road trip movie and, during the script, one of the main characters tells a story that we flash back to. The story, like Stand By Me, was eight pages long. The story, like Stand By Me, wasn’t directly connected to anything else in the plot.

The flashback was pretty good, mainly because the writer was good. But as I weighed the flashback’s impact, I couldn’t help but realize it took up a full 10% of the screenplay. 1/10th of the script was dedicated to a story that wasn’t connected to the plot. What I mean by “not connected” is if you were to eliminate the flashback, nothing else in the script would have to be rewritten. That’s the easiest way to identify if something is necessary in your script or not. If you can get rid of it and you don’t need to make a single other change anywhere? It probably wasn’t a necessary scene.

Analyzing this sequence brought me back to Jason’s Stand By Me class. Because I finally understood what he meant. If a scene is not moving the story forward, it’s either a) pausing it, or b) moving it backwards. As a screenwriter, you want to avoid both of those things. Pausing and going backwards are antithetical to keeping an audience invested. Therefore, you should avoid them.

What Jason was saying was that the screenwriters for Stand By Me, Bruce Evans and Raynold Gideon, knew this. They understood that each scene must push the story forward. And that this pie eating story tangent wouldn’t do that. However, they decided that the scene was still worth it anyway. I suspect they felt it helped viewers understand Gordie better, since it showed how talented a storyteller he was and gave us some insight into him as a person (since you can get a feel for a person by the kind of stories they gravitate to).

As screenwriters, making sure every scene moves the story forward is one of the most important pieces of advice we can follow. The scripts that derail the quickest are the ones where too many scenes aren’t pushing the story forward. Think of it like a car ride. As long as you’re moving forward, you’re happy. But the second you get stopped in traffic. Or the second you get stuck behind a long stoplight, you start feeling anxiety. You didn’t get in the car to stop. You got in it to continually move forward until you got to your destination. A script read works the same way. If there’s too much stopping (scenes that don’t push the story forward), the reader gets anxious. And, at a certain point, that anxiety hits a breaking point. We’re out.

Of course, that doesn’t mean you can never write a scene/sequence that doesn’t move the story forward. Like the pie-eating contest. As long as you recognize that it’s a gamble and that, therefore, the scene has to be amazing, you should be okay. Just don’t make a habit out of including these scenes. Jason was quick to point out that every other scene in the movie pushed the story forward.

The next project from the 10 Cloverfield Lane writers!

Genre: Sci-Fi (Short Story)

Premise: Set in the future, a former serial killer is “rightminded,” the process of digitally altering the brain to take away its psychopathic tendencies.

About: This short story from 2014 sold earlier this year for the 10 Cloverfield Lane writing team, Josh Campbell & Matt Stuecken, to adapt. The short story comes from Elizabeth Bear, who’s won two Hugo Awards, one for short story Tideline, with follows a sentient war machine that is the only survivor of an apocalyptic war that has reduced the human population to cavemen. And the other for her novelette, Shoggoths in Bloom, about the famed HP Lovecraft monster, the shaggoth.

Writer: Elizabeth Bear

Details: about 5000 words (you can read it here)

This idea of serial killers getting mind-altering treatment to take away their killing impulses is not a new one. I’ve probably read five full scripts covering the same subject matter over the past decade. But that’s not necessarily a bad thing. If lots of people are gravitating towards the same idea, that means there’s something to that idea. And if no movie of worth has yet been made with that concept, then why shouldn’t you be the one to do it?

It’s a reminder, though, that a good concept doesn’t naturally translate into a good script. The reasons for why vary, but mostly it comes down to weak writers exploring the most obvious route of the idea. That’s definitely not what we get today. This story is quite complex and gets you thinking. Which may be the reason why it becomes the version of this concept that finally makes it to the finish line.

Our unnamed narrator killed 13 women. And even though he’s been caught and placed in prison, he wants to kill more. In fact, when his female lawyer tells him about this new technology that can eliminate his impulse to kill, all he can think about the entire conversation is the number of ways in which he could kill her.

It’s hubris that dooms him, however. He doesn’t volunteer for the treatment because he wants to be a better human being. Quite the opposite. He plans to keep killing for the rest of his life. He volunteers for the treatment because he believes he can beat it.

Now here’s where things get a little confusing, so stay with me. In addition to changing your brain, the government wants to push you as far away from that killer as possible. So they also change your look and your insides. It is decided that our narrator will become a woman.

Back to present day, where our female narrator, who no longer has those impulses, is jogging on the outskirts of town during winter. A few minutes after helping a driver with directions, she’s attacked from behind. The directions were a ruse. And when our narrator wakes up, she’s in a cold dark basement. The situation is not unlike the scenarios she put her own former victims through.

But it’s that familiarity with what’s happening that allows our narrator to stay calm. She slowly and methodically picks away her restraints and then waits by the doorway for her captor to return. When he does, she viciously attacks him. But seeing as she’s now a woman, she’s much smaller and much weaker than before. It doesn’t look like she’s going to defeat him. At least the 13 families of the women she killed will be happy. Unless, of course, she can find one last burst of energy and get the heck out of here.

I liked this.

Bear is a strong writer. You can tell right off the bat that she has an ease with words, sentences, exposition, prose, that make for a more advanced read than you’re used to. “This cold could kill me, but it’s no worse than the memories. Endurable as long as I keep moving. My feet drum the snow-scraped roadbed as I swing past the police station at the top of the hill. Each exhale plumes through my mask, but insulating synthetics warm my inhalations enough so they do not sting and seize my lungs.” You feel like you’re in good hands, that’s for sure.

Let’s talk about the execution. Like I mentioned above, I’ve seen this idea before. What is Bear doing better than everyone else? That’s simple. She’s integrating irony into the execution. This isn’t yet another “helpless woman gets kidnapped by a serial killer” story. It’s about a serial killer who gets kidnapped by a serial killer. In other words, there’s a heavy dose of irony baked into the setup.

Now I’m not going to say the setup is perfect. Bear conveniently hurries through the explanation of why our narrator needed to be changed into a woman. Methinks Bear knew that the later kidnapping played better if our protagonist was a woman so just sort of threw some science fiction gibble gabble explanation in there as to why part of the treatment was changing the killer’s gender. But it’s one of the only weak parts of the story and since almost everything else was so well done, I didn’t allow it to destroy my suspension of disbelief.

Bear’s skills come into play the strongest when she has to write exposition. Exposition is the writing equivalent of fresh breath. When someone has it, you don’t think about it. But the second you smell bad breath, your romantic interest in that person nosedives. Same is true for exposition. Done well, you don’t notice it. Done poorly, and it’s all you think about.

There’s this sequence early on where the lawyer is explaining to the narrator (when he’s still a man) the process of “rightminding.” It’s an exposition-heavy exchange that would’ve tripped up a lot of lesser writers. But Bear does something clever. She intersperses the lawyer’s exposition with the thoughts of our narrator, who is thinking of the many different ways he’d love to kill her. It takes an average exposition-heavy scene and makes it interesting.

But the real accomplishment of this story is the complexity in which we see the main character. On the one hand, the protagonist is the only person we sympathize with. We’re in their head with them. So we want to see them survive. On the other hand, we know who they were. That they killed 13 women. So there’s also a part of us who wants to see this kidnapper kill our protagonist.

When everything is too straight-forward, it’s often boring. You want complexity of thought to be involved in parts of your story. It’s the same thing I talked about yesterday, with the amazing script, “Ambulance.” When all four parties converge on that ambulance, I was rooting for all for them, even though they weren’t on the same team. That’s when your script starts transitioning from 2-D to 3-D. It’s worth looking for storylines that create that kind of complexity.

One last gripe – the ending. Which I will kind of spoil here.

For all of their outstanding writing abilities, these talented award-winning short story writers all seem to have the same weakness, which is that they wimp out on the ending. They’re terrified of giving you a definite end, so they all cut out before a clear ending occurs. I’m sure lots of writers will defend this move. But what they can’t defend is that if I know exactly what your ending is going to be before you write it, you’ve chosen the wrong ending. And I knew Bear wasn’t going to tell us whether our narrator lived or died. So even though you picked the literary acceptable ending that English Professors would give you an A on, you failed the reader test. And we’re the ones who matter.

So PLEASE don’t make that same mistake with the movie version. Because this one has potential.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Never underestimate the power of movement. – This story starts with the narrator talking to us during a jog. The narrator’s thoughts themselves aren’t the most interesting in the world. Not to mention, there’s exposition in there. But it didn’t bother me as much as it usually does because the main character was moving. They were going somewhere. Even if that somewhere was just the end of the jog. I don’t know what it is about movement but it helps speed up otherwise slow sections. I suppose it’s a psychological thing. But I knew it was working when I thought how much more boring her thoughts would be had she been giving us them while sitting down on her couch. I was reminded of this while reading a recent screenplay that had a large flashback scene early on. You know how much I hate flashbacks. But the character who was sharing the flashback was in a car driving with his friend. The mere fact that we were going somewhere made that flashback more bearable.

Genre: Comedy?

Premise: (from IMDB) When an all-powerful Superintelligence chooses to study average Carol Peters, the fate of the world hangs in the balance. As the A.I. decides to enslave, save or destroy humanity, it’s up to Carol to prove that people are worth saving.

About: A lot of people will focus on the terrible Rotten Tomatoes score of Superintelligence (26%). But Superintelligence actually achieves a rarity for any comedy, which is to get a worse audience score (23%) than critic score. Audiences are always more forgiving with comedy than critics. Which means this must be a really really really really really bad movie. Melissa McCarthy teams up, once again, with her husband, Ben Falcone, who directed the film and basically wrote it as well. This winning combo has created Tammy, Life of the Party, and The Boss.

Writer: Steve Mallory (but from what I understand, Falcone and McCarthy basically told the writer what to write)

Details: 2 hours of hell

First of all, you’re probably wondering why I’m reviewing this. I’ll tell you. This is one of the worst pieces of professional entertainment I’ve ever seen. Normally, I’d take that in and move on with my life. But I can’t. I can’t because if there’s one thing that bothers me about this business, it’s when someone with less-than-zero talent gets millions of dollars to make movies.

I’m not dumb. I understand that untalented people weasel their way into every industry. And, truth be told, they only make up about 10-15% of those industries. But their level of ineptitude is so extreme, that it always feels like a lot more than that. And Ben Falcone has to be the single most untalented writer and director I’ve ever seen get this many opportunities in Hollywood.

Of course, he has an ace up his sleeve. He’s married to Melissa McCarthy, who, ironically, is one of the most talented people in the business. I’m a huge Melissa McCarthy fan. Go to Youtube right now and search “SNL Melissa McCarthy.” There’s a reason no SNL host has more video views than her. She’s hilarious. And that’s what makes this all the more frustrating. Falcone’s lack of talent isn’t just dooming him. It’s taking down someone who actually has talent. Someone who should be making much better movies.

I’m going to try to summarize the plot of Superintelligence for you. But I’m giving you advance warning that the nonsensical nature of everything you’re about to read is going to make it sound like I didn’t understand it. No, this was the actual plot.

Carol Peters – the nicest person in the world – lives in Seattle and is trying to find a non-profit job. She’s having some trouble and, yet, that doesn’t seem to play into the plot at all. In other words, if she fails to get a job, it doesn’t sound like it will affect her life in any way.

Why does this matter? Because, later, the Superintelligence will buy Carol a 5 million dollar apartment, a 100,000 dollar car, and put 10 million in her bank account. But since Carol has never needed or wanted money, these developments feel random and unimportant. I’m sorry. I’m getting ahead of myself.

Out of nowhere, the first ever self-thinking AI contacts Carol, presenting itself as James Corden, since Corden is Carol’s favorite TV personality. The AI says it’s going to destroy humanity in 72 hours. Why? No idea. Never says. Probably best we not get into the specifics as we will then find out that if he destroys humanity, he also destroys himself, which would make absolutely no sense. But what in this movie does make sense?

First, AI James Corden says, he wants to learn about humanity. And he’s ID’d Carol as the perfect guinea pig. Why did he pick Carol specifically, though? No idea. To Falcone’s credit, this question is asked like 50 times in the movie. And yet, nobody answers it. Even AI James Corden answers it once and we don’t understand his explanation. ANYWAY!

To learn about humanity, AI James Corden asks Carol what she would do if she only had three days to live, since she does. She says make things right with her ex-boyfriend, George. Coincidentally, in the only attempt at writing an actual screenplay, George is moving to a new city in three days. So Carol better hurry up! Wait a minute. Do we even need a ticking time bomb with the George relationship if the earth is going to blow up in 3 days? Oh, who needs logic in screenwriting? MOVING ON!

As if understanding just how bad this script is, AI James Corden attempts to help out, giving himself a motivation for why he wants these two to be together. He wants to “better understand humanity” you see. And seeing if Carol can rekindle her relationship with George will somehow… achieve this? Maybe?

Quick plot summary break here cause I’m about to explode with anger. This script is so bad that I am positive it would finish fifth in voting an any Scriptshadow Amateur Showdown. That’s how bad this. It can’t even beat an average amateur screenplay. One of the primary issues with a bad script is that every screw is loose. It’s not clear why James Corden is going to blow up the world. It’s not clear why he wants Carol and George to rekindle their relationship. It’s not clear what Carol’s financial situation is or why she can be eternally jobless and not have to worry about money. Every single aspect of the script is vague. That’s bad writing. And for screenwriting this bad to be produced? Shame on these people. Seriously. Shame on them.

Sorry, I got distracted again. Where were we with the plot? Oh yeah, so the US Defense Department gets wind of the AI and is going to turn off the entire internet except for one small computer, trapping the AI there and then killing it, which is the only well thought out plot point in the entire movie. But AI James Corden gets wind of this and makes it impossible to turn him off.

However, at the last second, he has a change of heart when Carol does something unexpected (she doesn’t tell George about the impending doom). This makes AI James Corden realize that he has a lot to learn about humanity, so, okay fine, he’ll keep them around for a while. The End.

First of all, James Corden. You need to do better. You’re very talented but you’re George Clooney level at picking your projects. Have your agent start picking them for you.

Okay, maybe I can take a break from being so angry and use this opportunity to teach some lessons here. Unlikely but I’ll try.

Concept. When a concept is weak, nothing you write will matter. A concept is what forms your movie. It is the initial structural beam. Without a strong one, you’ll spend your entire script in “search mode,” where you’re searching for the story. Guess what, you won’t find it. You need to have done the work in the concept stage.

Superintelligence is not a concept. It’s a concept fragment. The only part that has concept potential is the superintelligence part. But then you need something that the superintelligence interrupts that is clever or ironic or has some form to it. A superintelligence studying an average person is not a concept. A superintelligence studying the dumbest person in the world still isn’t a movie-level concept, in my opinion, but it’s better. The irony of the highest intelligence trying to learn from the dumbest intelligence has some irony baked into it.

The biggest clue that this isn’t a concept is that you would have the exact same movie without the superintelligence part! This movie is about a woman who reconnects with an ex-boyfriend. You didn’t need the superintelligence for that. Like we already established, you didn’t even need the 72 hours before planetary destruction since George was moving out of town in 72 hours himself. EXACT. SAME. MOVIE.

Sure, you wouldn’t have had the AI buying Carol a car or a nice apartment. But like we established, those things had zero impact on our heroine. If our protagonist had been dirt poor and always wanted money, those purchases would’ve mattered. It could’ve been a Cinderella type situation or a “be careful what you wish for” film. But that’s how bad the screenwriting was here. They didn’t even know to marry the character situation to the concept. They were two completely different things that they attempted to mash up against each other the whole movie in some desperate attempt at comedy.

This shows what happens when there is no oversight, no pushback, no conflict, in development. That’s the thing I don’t understand with writers. They’re afraid of feedback. Afraid someone is going to tell them their idea sucks or their character sucks. BUT THAT’S EXACTLY WHAT YOU WANT!!! You want pushback. You want people to say, “No, that doesn’t work.” “No, that’s boring.’ Because then it forces you to go back in there and come up with something better. That’s how good movies are made.

The reason you can tell that nobody pushed back here is because everything that occurs in this movie occurs easily. Carol lives an easy life. We know the AI is never going to hurt Carol. We know Carol isn’t going to encounter much resistance getting back with George. There isn’t a lick of genuine conflict at any stage at any point in this movie.

It’s so badly written that I believe this script should be commemorated by all major film schools as the defining example of how not to write a screenplay. Every single choice in this script is wrong. I’m serious. Every one. If you made the exact opposite decision on every one of these story choices, you would likely come up with something great. That’s how misguided this was.

I don’t know how you can be this bad. You have to try to be this awful at something.

This goes down as one of the worst movies I’ve ever seen in my life.

[xxx] What the hell did I just watch?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the stream

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: If you want to pay something off, you actually have to set it up. I didn’t know that people were so dumb that they’d need to be told this. But apparently, it’s the case with Ben Falcone. So there’s a scene around the midpoint where Carol takes George to a Seattle Mariners game and former Mariner great Ken Griffey Jr. comes to say hi to them and George nearly has a seizure. Ken Griffey Jr. is saying hi to him! Oh my God! This is amazing! He takes like 50 selfies with him and can’t stop talking to him. There’s only one problem with this moment. It was never set up. We were never told, before this moment, that George was a Ken Griffey Jr. fan. We were never told he was a Mariners fan. Heck, we were never even told he liked baseball!!! Which made this freakout session bizarre. Had a, you know, real screenwriter been in charge of this, they would’ve mentioned several times early on how big of a Mariners and Griffey Jr baseball fan George was, which would’ve helped this scene play a lot better.

Genre: Comedy/Drama

Premise: Two scientists must go on a press tour to answer questions about an impending asteroid collision that will destroy all life on earth.

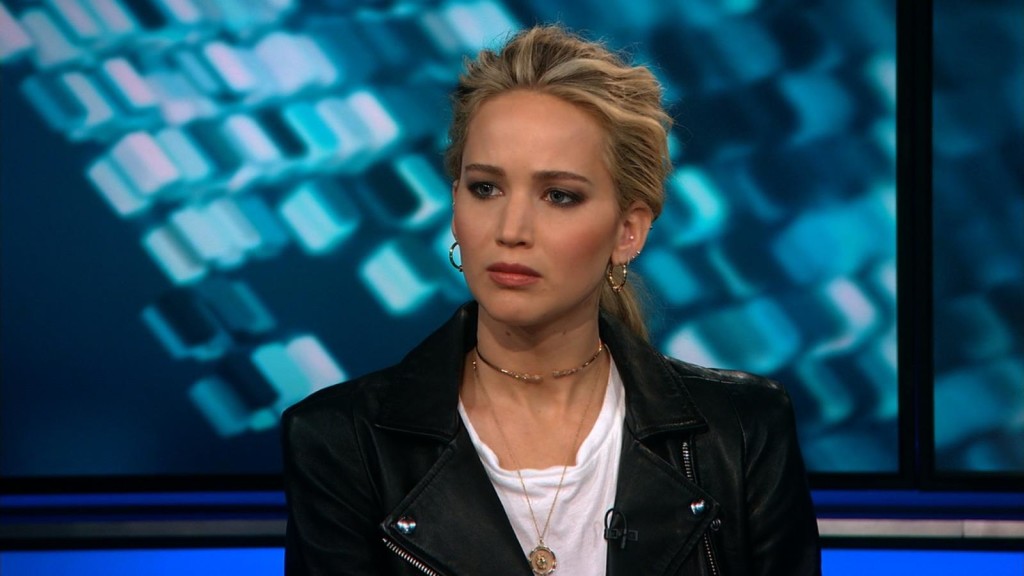

About: Big one today, guys. Some might even say it’s an extinction-level script. This is the big Adam McKay Netflix project that’s to star Leonardo DiCaprio, Jennifer Lawrence, Jonah Hill, and Timothy Chalamet. Of his return to comedy, McKay said, “I don’t think it’s a ‘Step Brothers’-type of comedy. I would compare it more to somewhere between the Mike Judge stuff and ‘Wag the Dog.’ A hard funny satire is what we’re going for.”

Writer: Adam McKay

Details: 125 pages (Jan 2020 draft)

There aren’t too many scripts I get excited for these days. I’ve read so many screenplays and so many writers that I pretty much know what to expect when I open a script. That all changes today. Today’s screenplay combines a guy who I believe is one of the most talented in Hollywood, Adam McKay, with a unique idea. It also has an interesting cast. I mean, who would’ve thought that Leonardo DiCaprio and Jennifer Lawrence would ever work together? I can’t think of two people more polar opposite. All of this implies that we’re getting something special. Famous last words, right? Let’s jump into it.

Scientist Kate Dibiasky works for tenured Michigan State professor Randall Mindy. During a party, Kate does a little work and, while tracking a comet, watches it collide with an asteroid, which then sends the asteroid on a collision course with earth.

Kate tells Randall, who confirms with everyone in the department that, yes, this thing is going to hit and destroy earth in six months. So they call the White House and get a meeting with the president, but to their dismay, the president says they want to sit on this information for three weeks, as they don’t want to throw any wild variables into the upcoming election.

Since every second passed is one more second the world isn’t stopping this asteroid, Kate and Randall go on a publicity tour to warn the world, in the hopes that it motivates our government to stop this thing. Except the exact opposite happens. Nobody takes them seriously. Even on the big shows, their interviews don’t trend. Everyone thinks their story is cute but, you know, not likely to be true.

As Kate gets angrier and angrier, Randall starts to cozy up with the White House, despite the fact that they’re not doing anything. Which makes Kate even angrier! Eventually, even the president can’t deny that this asteroid is coming for them. And so they FINALLY come up with a plan to send nukes at the thing and knock it off course.

But during the launch, just as the nuke delivery guy has made it to space, he TURNS AROUND. What’s happening, Kate demands. Well, it turns out the Elon Musk-like Peter Isherwell has discovered over 4 trillion dollars worth of gold and diamonds on the asteroid. He’s made a deal with the White House to use a series of drone-nukes that will latch onto the asteroid at strategic spots, blow it up into small pieces, which they can then mine from the ocean.

The problem with this plan is that the asteroid is now so close that if something goes wrong, they won’t have another shot to destroy the thing. Will they be able to pull this mission off? Or is everyone going to die because no one will acknowledge that this great big asteroid is really going to hit us?

One of the first questions that popped into my head while reading this was, “Why did Leonardo DiCaprio agree to make this movie?” The character of Randall isn’t like anything he usually does. I don’t remember the last time DiCaprio did comedy. I guess he’s sort of comedic in Tarantino’s movies. But I don’t think he’s ever done satire, has he?

Anyway, it all became clear when I realized this movie was an allegory for global warming. It’s about the fact that there’s this giant asteroid coming at us but nobody wants to “look up.” They all stare at the ground and ignore it in favor of the latest tick tock drama or what sexual misgiving the newest supreme court nominee engaged in 30 years ago. Global warming is DiCaprio’s passion (even if he likes to fly private jets everywhere). So if you share DiCaprio’s passion for this subject matter, you too, will probably enjoy this.

As a story, though, I had trouble getting into it. Satire has never been my thing. So that’s part of it. But the bigger part is that I didn’t care about Kate or Randall. And isn’t that what it always comes back to? It doesn’t matter if you have a great plot. It doesn’t matter if you’re passionate about the subject matter. If we’re uninterested (or even casually interested) in your characters, it’s not going to work.

Kate is one-note. All she does the whole time is be pissed off. That’s it. She tells people about the asteroid and when they don’t take it seriously she throws up her hands and says, “I’m done.” When you repeat the same beat over and over again for a character, that character becomes boring quickly.

Randall is a little more complex. He’s got this cheating scandal going on and he eventually turns to the dark side by cozying up with the president. But I never got a handle on him at all. At least with Kate, I could designate her. She was “the angry character.” You could give me all the time in the world and I still wouldn’t be able to tell you what kind of person Randall was.

This is why I remind writers, early on in their script, to figure out your character’s defining trait. Joker wants to fit in with the world. Jordan Belforte is addicted to excess. In Run, the mother loves her daughter too much. I don’t have any idea what Randall wants. And that hurts the story because if you have one character who’s too thin and another who’s undefined…. You don’t have a movie.

I’m going to make a grand assumption here and guess that McKay was so set on exploring his theme that he overlooked the people delivering it. This happens to all writers. Whenever we start a script, we have a specific reason we want to write it. Maybe it was the concept, a character, a theme, we want to tell a breakup story because we just went through a devastating breakup. Whatever it is, it’s often specific. What happens, though, is we develop a blindspot to everything else in the story. Those other variables aren’t the reason we wrote the story so we don’t care about them as much.

The script does have some funny moments. There’s a whole thread about “impact deniers.” Congress doesn’t initially approve the “Save The Planet Bill” due to partisan politics. The woman Randall has sex with gets off on being told the specific scientific ways the asteroid is going to destroy the planet. And there was the occasional funny line, such as this exchange in an early interview on a news show – Kate: “Well, it became apparent that the large asteroid’s orbit was changed by the hit, the collision… and it is now on a course to directly and catastrophically hit earth in just over five months.” Newsperson: “Now how big is this rock? Could it damage say, someone’s house?”

Also, even though I wasn’t that invested in the story, I did want to read til the end. There’s something to be said about a strong hook and wanting to see how that hook is resolved. I genuinely did not know, until the last 15 pages, if McKay would have earth get its s%$# together or kill everyone off. So at least I was uncertain where the story was going, which is more than I can say for most of the scripts I read.

But I don’t know, guys. I’m neutral on the script’s theme. The main characters were average at best. I didn’t laugh as much as I hoped to. And satire is one of my least favorite genres. When you add all those things together, you get my lukewarm response. It seems like a good movie to put on Netflix though. I’m not convinced something this off-center could have been produced for theatrical distribution. What do you think?

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Spec screenwriters should stay away from the satire genre. It’s one of those genres, like dark comedy, where the execution bullseye is microscopically small. This tends to be a “showoff” genre anyway. A genre for those who like to prove how smart they are. But even if you’re good at it, the chances of you sticking the landing on one of these scripts is incredibly small. Therefore, I’d steer clear.

A funny thing happens when you read a ton of scripts in a row. Especially the way I did it over the weekend. I needed to finish all the entries and I was running out of time since I had to post the semifinalists Monday, so I had zero breaks. As soon as I finished ten pages of one script, I put it in a pile and immediately opened up the next one.

When you’re reading that much, an almost “Matrix-like” clarity comes over you about what really matters in the first ten pages (and, by extension, the script). I realized that all I cared about were two things. One, give me an entertaining scene that grabs me. And two, introduce me to somebody I care about. If you do one of those two things, I’ll read on. If you do both of those things, I’m *excited* to read on.

Let’s unpack this because we talk about these things all the time, but I’m not sure everyone knows why they’re important other than they hear people like me say they are. Too many screenwriters approach the craft from a subjective point of view. They think that because they are writing something, the script will automatically be interesting. It is their belief in themselves that guides their decisions.

So, for example, if they like ‘driving and talking’ scenes, they might start the script with a married couple driving and talking and simply assume that because they like that scenario, other people will as well. But two people talking while driving without anything else going on is a poor scene prompt. In all likelihood, it isn’t going to yield an interaction that a third-party (the reader) would enjoy.

The mental shift writers need to make is to stop seeing their script from their own selfish point-of-view and start looking at it from an OBJECTIVE point-of-view. Transport yourself into the reader’s head then ask if what’s on the page is entertaining *to that person.* It is from this perspective that you will more likely generate a strong scene.

From there, you either come up with a new, more entertaining scene prompt, or you can reimagine the current scene in a more entertaining way. The best way I’ve found to do this is to inject a problem into the scenario. A problem achieves three things. It forces your characters to act. It forces your characters to make choices. And it creates conflict between characters. Because, often, when two (or more) people are faced with a problem, they have different ideas about how to deal with it. And those ideas conflict with one another, resulting in an interesting dialogue.

So if we’re going with this car scene. What if, instead of them driving in the car, we start with them on the side of the highway, their car having broken down. This is our “problem.” Already, it’s a more interesting situation because we’re curious how they’re going to resolve the problem. And what good writers will do is they’ll add factors that pressure the characters, which make the situation even worse.

For example, if this were a married couple, maybe Doug, the husband, dragged his feet all morning even though, Lucy, his wife, stressed to him how important it was that they be on time today because she has a huge meeting. So they’re already late as it is, and now their car has broken down, and she’s got a huge meeting. Look at how much more interesting the dialogue is getting. He might want to call AAA to get the car towed first but, since she’s in such a hurry, she wants to get an Uber, now! That’s what they’re arguing about.

And we can go even further. Maybe they have a 4 year old daughter they’re taking to pre-school. And it’s burning up outside. And she’s in the back of the broken car and now she’s burning up. And so Lucy is already furious that Doug has put them in this position but now their daughter’s safety is in danger. You can see how introducing a problem and then building little agitators into that problem can take a boring car driving scene and turn it into this intense compelling opening.

I’m not sure writers who see writing through a subjective lens can come up with that scene. It’s only writers with an objective mindset that come up with scenes that entertain others. Now there is a writing philosophy out there that goes something like, “Write whatever you want and, if you like it, others will too.” While I’m not going to completely dismiss that philosophy, it relies more on luck. When you completely dismiss the audience and write for yourself, you tend to come up with blander, less dramatic, more pretentious stories.

And, by the way, you shouldn’t be thinking this way ONLY for the opening. The opening may be the most important scene since it’s the scene that either hooks the reader or doesn’t. But you want to take that attitude into every scene in your script. Ask yourself, is the reader being entertained right now or am I assuming they’re enjoying themselves because I’m writing words for them and I’m a good writer?

The other way to hook a reader is to introduce a character who’s instantly intriguing in some way. They are a ‘hook’ in and of themselves. This is the harder route to go, for sure, because character is the hardest thing to get right in screenwriting. Most characters in scripts read like characters when they need to read like people.

There are lots of theories on how to construct a character that feels real and lively and compelling. But I’ve found the starting point is always a commitment to creating a compelling character in the first place. I know that sounds obvious but it actually isn’t. Most writers come up with an idea, start writing the script, and figure out the characters along the way.

If you want to write a strong character, you must think of them apart from your story. This is how Wes Anderson created one of his most famous characters ever, Max Fischer, from “Rushmore.” He and Luke Wilson started with Max, tried to make him as weird and unique as possible, and only then did they come up with a story for him. I dare anybody to go watch that movie and not come away mesmerized by that character.

So you first have to make that mental commitment. Then use your first scene as a resume that lets the reader know what they’re going to be getting. I have a couple of examples for you. The obvious one is “Joker.” Joker, the movie, doesn’t even really have a plot. It’s just this really weird damaged person trying to fit into society who keeps getting kicked down. And that’s how we meet him. He literally gets kicked and beaten down. You want to keep reading after that opening scene SPECIFICALLY to see what happens with that character.

Another example is Cassandra from the upcoming movie, “Promising Young Woman.” That script starts out with a really drunk woman at a bar who gets picked up by a seemingly cool guy who then tries to take advantage of her back at his place, only for her to reveal she’s stone-cold sober and exposes his motives. This woman goes around doing this all the time. But what really makes her interesting is that she doesn’t know where the line is. Is she a hero? Or is she a villain? That’s when you really get into “interesting character territory,” when the answer to that question isn’t easy.

By the way, you’ll note that both Promising Young Woman and Joker started with entertaining scenes. Joker has his sign stolen that he’ll have to pay for if he doesn’t get it back. And we’re pulled into Cassandra’s situation because we’re worried for her. We see this wounded animal at a bar and think she might be in danger. That’s the ideal way to do it. Start with an entertaining scene AND a compelling character. Those always turn out to be the best scripts.

This topic is obviously more nuanced than 1500 words allow. There are scenarios where two people in a car talking can be entertaining, such as if you have strong dialogue skills able to carry a scene all by themselves. And there’s a discussion to be had about how writing for yourself can lead to some off-the-wall weird stuff you’d never be able to tap into if you’d focused solely on pleasing others. So I’m not saying you have to do it the way I’ve laid out.

All I can tell you after reading that many pages in a row is that the scripts that suffered the most were the ones that started with a weak or common scenario and had bland or simplistic characters. Your two most important components are your story and your characters. If you can’t make either of those pop in the first scene, why would anyone keep reading? This article is a game plan to tackle that. I’ll leave it up to you whether you want to use it or not.

Carson does feature screenplay consultations, TV Pilot Consultations, and logline consultations. Logline consultations go for $25 a piece or $40 for unlimited tweaking. You get a 1-10 rating, a 200-word evaluation, and a rewrite of the logline. They’re extremely popular so if you haven’t tried one out yet, I encourage you to give it a shot. If you’re interested in any consultation package, e-mail Carsonreeves1@gmail.com with the subject line: CONSULTATION. Don’t start writing a script or sending a script out blind. Let Scriptshadow help you get it in shape first!