Search Results for: F word

Genre: Sci-Fi

Premise: The leaders of a planet journey to a new planet in a quest to gain control of a rare powerful substance called “spice.”

About: Dune is one of the biggest gambles in movie history. A 250+ million dollar production based on a 50 year old novel catered heavily to adults. It is dense and heady, two words studios detest. Nevertheless, they gave the film to “Blade Runner: 2049” director Denis Villeneuve and stacked it with the best cast this side of Once Upon a Time in Hollywood. Oscar Isaac, Timothee Chalamet, Zendaya, Jason Mamoa, Josh Brolin, Dave Bautista. The film was supposed to come out next month. But they were forced to push it to next fall due to the Corona virus. The original adaptation was done by screenwriting superstar Eric Roth. In a strange Hollywood twist, Jon Spaihts left a separate Dune TV series to write the final draft of the feature film.

Writer: Eric Roth and Denis Villeneuve (current revisions by Jon Spaihts) (based on the novel by Frank Herbert)

Details: 134 pages

My oh so conflicted Dune heart.

There isn’t a property I haven’t wanted to like more than Dune. A serious sprawling sci-fi fantasy story is something I should theoretically love. And yet every time I’ve tried to read the novels, I fantasize about getting a lobotomy.

But here’s what I’m hoping with the Dune script. I’m hoping that Roth and Spaihts have stripped away all of that boring muckety muck from the novel so that we get a cool stripped down enjoyable story. I don’t need 50 pages of backstory on how Greta Mogf’flox came to find her love for the art of noxela, that of the space ballet.

Give me a clear story, make it entertaining, and I’m in. Did that happen?

16 year old Paul belongs to a House that, I think, runs his planet. But Paul, along with his father, Duke Leto, and his mother, the prostitute Lady Jessica, only care about one thing – the SPICE! The spice is, essentially, a drug that allows for you to live a heightened life. It makes you healthier, smarter, even supernatural, since some people can use it to see into the future.

The problem is that the spice only grows on one planet – Arrakis. So all the surrounding planets come there to mine it. This is where things get confusing so I apologize if I get this wrong. I believe the people of Arrakis extend an invite to Duke and Paul, to come have a bigger controlling interest in the spice. They’re actually inviting a lot of Houses from neighboring planets there, including the House of Harkonnen, led by Duke’s rival, the 600 pound BARON VLADIMIR HARKONNEN.

Once they get to the planet, everything seems cool, if a little tense. When Duke and Paul learn that some spice miners are stranded in the desert with a potential giant Dune worm after them, they grab a hover ship and go save them. This is where they learn that mining spice is dangerous. At any moment a super worm can eat you up. I guess they like spice too!

Eventually, Paul, Duke, and Lady Jessica, learn that they’re being played by Baron Harkonnen! Harkonnen throws Paul and Jessica out in the middle of the desert while torturing Duke. He wants Duke to know that he’s eliminating his bloodline so that the Harkonnen can be the sole rulers of the spice! Talk about a spicy offer.

Back in the desert, Paul and his mom must avoid giant worms in the middle of the night. They barely survive until their clan’s top warrior, Duncan Idaho (Jason Mamoa), rescues them. They must get back to the city to stop the Harkonnen (along with the evil Emperor’s bloodthirsty army) from turning the planet of Dune into their own personal spice playground. Will they succeed? No one knows except for Timothee Chalamet!!!

I’m going to be straightforward with you here. This movie is in a LOT of trouble.

The issue is simple. It’s boring. At least for the first half of the movie it is. From there, it has some moments but mostly stays boring.

This was always my worry with Dune. I could never get into the book because I’d get bored quickly. The 1984 movie version of Dune was also boring. And now we have this film, which, even with the talent in front of and behind the camera, is stuck drawing from the same source material. So you have to wonder, is this story just boring?

Maybe we can answer that by asking what the screenwriting definition of boring is. Well, boring is in the eye of the beholder, of course. But there are certain concepts and setups and narrative choices that lend themselves to a more objectively boring experience. And Dune checks a lot of those boxes.

One, you have a ton of mythology and world-building. The more mythology there is, the more exposition you’re going to need. That means characters explaining things. The more your characters are explaining things, the less they’re ACTING UPON THINGS. Movies are about character ACTIONS. Not about WHAT THEY SAY. So if you’re doing something that’s keeping your characters from acting upon the world, you’re keeping them from engaging in a good story.

Next, you have a plot that moves slowly. There aren’t a lot of significant plot beats in your script. We cut from scene to scene without much forward movement in plot. Another way to put it is, after reading the tenth scene, a reader shouldn’t feel like they’re no closer to the purpose of the story than after reading the first scene.

Next, you have a lot of SAT scenes (Standing Around Talking). You guys know much I hate SAT scenes. It’s nearly impossible to keep an audience engaged when the only thing characters are doing is standing around talking to each other. And that’s the first 15 scenes of this script. It’s one SAT scene after another.

The only way this is going to work for audiences is if you’re one of those people who really loves deep rich mythologies. To you, it’s fun learning about this world. You don’t need a story to keep you engaged. But that’s a small percentage of moviegoers. Most moviegoers want a story.

Look no further than Dune’s fantasy movie cousin, Lord of the Rings. That film does it right. It sets up the mythology but it establishes the stakes, what the goal is, the journey ahead, how dangerous it would be, who needs to be involved, all very quickly. We then move into the journey, which ensures that the plot is always bopping along.

The first action scene in Dune doesn’t happen until the mid-point and I couldn’t even tell you what it was about. They hear some miners are in trouble. So they race out and save them. Encounter a sand worm. And survive.

Um, okay. That’s a scene. But here’s the problem. When they come back from that scene, EVERYTHING IS EXACTLY THE SAME. The story hasn’t moved forward. All that’s happened is they went off on this little side quest to save some people and now it’s back to bickering with the bureaucrats. Why am I 65 pages in to a 130 page script and I still don’t know the goal of our main characters??

Once Barron Von Fatso starts deceiving Paul and his family, things get a *little* more interesting. But not much. At least someone is finally acting (it’s a villain instead of a hero but, hey, something is better than nothing). But this plotline had its own issues. For example, we’re told from the start that Barron is up to something. So his deception was the most predictable twist ever.

Then, the plot is still static. Everything is happening in this one 50 mile range. Nobody’s going anywhere. We’re all standing around, ordering things, yelling at each other, people are sent out to the desert, they come back in from the desert. Contrast this with Star Wars or Lord of the Rings or even yesterday’s film, Love and Monsters. We’re moving forward in these movies. Dune, this purportedly giant universe, keeps all its characters in this tiny little area and has them play hide and seek with each other.

Ultimately, Dune is doomed by an old Scriptshadow mainstay. Burden of Investment. A high Burden of Investment is when the amount of information the reader is required to remember so outweighs the reward of remembering that information, that the experience doesn’t feel worth it. Or a more simplistic way to put it is, when a screenplay feels more like work than play, you’ve failed.

I will always respect the world-building that Frank Herbert did. I know how long that takes. But you still have to know how to tell a story. I’m not convinced that Herbert knew how to do that. Which is why everyone has such a tough time adapting this material.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Side-quests. Avoid “side-quests” in screenplays. They may be fun to do in video games. But if you’re sending your characters off on a 15 page sequence (12% of your entire movie), it better move the story forward. Here, we get Paul and his father going to save some stranded miners. Sure, it’s an okay scene. Yay for our heroes being heroic. But it didn’t move the plot along one inch. Contrast this with Obi-Wan and Luke going to Mos Eisley. That sequence moves the story forward because they’re trying to find a pilot in order to get to Alderaan. It actually gets them one step closer to their final goal. Maybe that’s why this script is a big fat fail. There’s no goal!!! Or, if there is, it’s buried underneath so much gobbledy-gook that only hardcore Dune lovers have put in enough effort to figure it out.

Genre: Period/Supernatural

Premise: (from Black List) A young slave girl named Lena has telekinetic powers she cannot yet control on a plantation in the 1800s.

About: This script finished on last year’s Black List. The writer, Sontenish Myers, an NYU grad, received the Tribeca Film Grant to make the film. The Tribeca Film Grant provides film budget grants for under-represented groups.

Writer: Sontenish Myers

Details: 114 pages

The other day I was talking to someone who is not in the screenwriting world. They like movies but they’re by no means obsessed with them like you and I are. Anyway, she was curious about my job, particularly when it came to deciphering the difference between a good script and a bad script.

“It’s all subjective, right?” She said.

This is not the first person I’ve run into who believed that the only difference between one script and another is the subjective nature of who reads it. The variable these people never consider is that a script must meet a basic standard of quality before it can be judged subjectively against other scripts. If it has not met that standard, then it is objectively not as good as other professional screenplays.

I don’t know if everyone here remembers Trajent Future and his bullet time dreams. But that classically bad amateur script was objectively worse than its professional brethren.

The question I then get is, how do you objectively know the difference between a beginner script and a professional script? Well, that answer is long and varied because there are a lot of things one must learn to write a professional-level script. But we’re going to go over a couple of ways to spot a problem script today to give you a feel for how readers assess these things. Let’s take a look.

The year is 1802 and 11 year old Lena is a slave on a cotton plantation with her mother, Alice. We learn early on that Lena can make things levitate. Like bottles or buckets of water. As a kid, she has fun with the power despite the fact that her mother keeps reminding her that if anybody finds out about this, they’re dead meat.

One day the decision is made to bring Lena inside and make her a house slave. So she and her mother are split up. Lena then tries to befriend all the other house slaves (all of whom are older) to mixed results. She also struggles to keep her telekinesis under control.

Then, one day, when she’s out getting water, a mysterious black woman approaches her and takes her back to her secret underground home. She’s seen Lena use her powers and wants to help her hone them. This interaction leads to the best exchange in the script. “Why do you live down here?” “Down here I’m free, up there I ain’t.” “Freedom is a lot smaller than I thought.”

In addition to Lena’s weekly telekinesis lessons, she also finds a 14 year old slave – Koi – who ran away from a neighboring plantation. Lena introduces Koi to the mysterious underground witch woman who feeds him and prepares him for his next journey.

After weeks of daily chores and strengthening friendships with the other house slaves, Lena’s worst nightmare comes true – her mother is sold. Lena slips away to Koi and the Telekinesis Witch and demands that they do something – use their powers to get her back. But will the two help Lena? Or do they consider the task too risky?

“Stampede” is an example of a common beginner concept mistake. A writer will give a character a power and believe that that power has given them their story. Unfortunately, it doesn’t work like that. Giving Lena telekinesis doesn’t give you a screenplay. All you’ve done is give your character a trait, not unlike the ability to play baseball or be a really good businesswoman. What about your story? What is going to happen that will make that trait interesting? That will put that trait to the test? Most beginner writers don’t know the difference between the two and therefore cobble together a disjointed narrative while occasionally going back to the power in the hopes that it will do some heavy story lifting.

Look at Get Out. The beginner screenwriter version of that is a black man dating a white woman. That’s it. The writer hasn’t thought beyond that. But the veteran screenwriter knows that all he’s done is set up the characters. He still has to come up with a story. So he adds that the girl is taking the boyfriend to meet her parents for the weekend and something bad is going on at their home. We never get anything like that in Stampede. It’s a narrative with no singular focus.

To be honest, I think this script would’ve been a thousand times better without telekinesis. The telekineses only serves to distract from the more poignant story about a young slave. It also makes the reader keep waiting for the telekinesis to become a bigger part of the story. And since it’s only a minor component, we never get that payoff. That makes the power a story distraction rather than a story ally.

Also, it seemed like there were better directions to take the story. But, in another common beginner mistake, the writer always took the path of least resistance – the path that made it easiest to write. You want to do the opposite. You want to go in those directions that are scary for you and harder on your character. If the slave owners would’ve discovered Lena’s powers, for example, maybe they try to use them for their own nefarious goals. Teaming up a slave and slave owners is where you’re going to find those messy but more interesting storylines.

But the biggest problem with the script is that the narrative isn’t purposeful. There is no goal. There are little, if any, stakes. And there’s definitely no urgency. Combined with the fact that the hero is stuck in one location, the story feels passive. There’s nothing for the characters to do. This leads to the writer coming up with all these small side stories, like the witch, like the 14 year old slave boy, like the friendships with the other slaves, that have no narrative thrust. There are no engines beneath these stories so whenever we’re participating in them, we’re asking ourselves what the point is.

How do you give a script narrative thrust? Simple. You create a big goal with high stakes attached. At around page 90 in this script, Lena’s mother gets bought by another slave owner and taken away. I’m not going go into some of the ancillary problems with this plot choice (we hadn’t seen the mom for 65 pages so we didn’t feel anything when she was sold). But what you could’ve done that would’ve been a lot better for the plot is to have the mother bought on page 25, the event that forces Lena to be moved into the house. Now you have a clear goal – Find and reunite with her mother again. It really is as simple as that. And that doesn’t mean you have to send her off on the journey. The entire movie can be her planning her escape and how she’s going to get to her mother and then the final act is her executing the plan.

Finally, you need your super-power to connect to your story better. Or else it just feels random. And that’s how this power felt. What does lifting bottles up have to do with anything in this subject matter? There’s literally zero connection – plot wise or theme wise. This tends to be another beginner mistake. The young screenwriter gets so hung up on the thing that they personally think is cool (in this case, telekinesis), that they never consider whether it’s relevant to the story they’re actually telling.

Last week, with The Paper Menagerie, the mother character had the power to make origami animals that came alive. That power had a ton to do with the story. It was cultural. It was the only way she knew how to connect with her son. They were a poor family so those animals were the only toys he had. They were also his only friends. And the animals ended up having messages within them that gave us our surprise ending. In other words, the power was organically connected to the story. We never got that here.

This script was just way too messy for me. I’m kinda shocked it made The Black List.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Period stories tend to work best when they’re set during a time of transition. All I could think while reading this was how much more intense it would’ve been had it been set in the months leading up to the end of slavery. The slave owners would’ve been more on edge. There’s uncertainty in the air. There’s more anger and, therefore, more potential for violence. This script was definitely missing an edge. That could’ve provided it.

Genre: Sci-Fi

Premise: An archeologist father and his young daughter must attempt to decipher an ancient alien message on a distant planet.

About: This is the big package that is bringing back a lot of the same team from “Arrival,” as this is another thinking man’s sci-fi story. The short story comes from Ken Liu. Shawn Levy of 21 Laps is the one who purchased it.

Writer: Ken Liu

Details: Short story about 15,000 words (an average screenplay is 22,000)

I’ve been all over Ken Liu since reading his amazing short story, The Paper Menagerie. When I heard he’d be teaming up with the new king of Hollywood, Shawn Levy, to adapt his short story, The Message, into a movie, I couldn’t remember any project announcement that got me more excited this year!

But one thing I’ve realized as I’ve studied Ken Liu is that he’s realllllyyyy smart. Intimidatingly so. Check out this answer he gave in a recent DunesJedi interview regarding his approach to science fiction versus fantasy…

“I think of all fiction as unified in prizing the logic of metaphors over the logic of persuasion. In this, so-called realist fiction isn’t particularly different from science fiction or fantasy or romance or any other genre. Indeed, often the speculative element in science fiction isn’t about science at all, but rather represents a literalization of some metaphor. I like to write stories in which the logic of metaphors takes primacy. My goal is to write stories that can be read at multiple levels, such that what is not said is as important as what is said, and the imperfect map of metaphors points to the terra incognita of an empathy with the universe.”

I’ll have to get a doctorate in Smartness at MeThinkGood University before I’m fully able to digest all of that. But the parts I did understand speak to one of the debates we’ll have later on. “The Message” has a lot of pressure on it as it’s coming after the perfection of The Paper Menagerie. Let’s see if it delivers.

Our story takes place in the way-off future. Our narrator, an exo-planet archeologist, flies around the galaxy to ancient civilizations in order to learn about extinct alien races. They’ve found a lot of these civilizations. But, so far, nobody has been able to find a LIVING alien race.

Just before he’s about to explore his latest planet, the narrator learns that his wife has died and he must now take care of their 11 year-old child, Maggie. He’s never even met Maggie so how do you say “awkward” in archeology-speak? Due to the fact that they’re going to blow up the latest ancient civilization planet soon, the narrator doesn’t have time to drop his daughter off and must bring her along.

Together, the two walk around the pyramid-infested city, which died off over 20,000 years ago. Their goal is to decipher “the message.” There are a lot of hieroglyphics everywhere and he’s convinced they’re all trying to say something. With the help of Maggie, who’s also into archeology, they do their best to decipher all the mysterious pictures.

Meanwhile, Maggie passive-aggressively needles her father about prioritizing his work over staying with the family and raising her. Why the heck does he care more about long-dead alien civilizations than his own family?? It’s a good question that takes a back seat when the dad finally cracks the message (spoiler). The message is that this is a highly radioactive area. Stay away. Stay away. Stay away.

This means they are both dying quickly. The dad can put Maggie in stasis which will halt the radiation poisoning until they get her to a hospital. But since the ship was damaged during landing, the dad will need to manually fly it back up into the atmosphere. By that point, the radiation poisoning will have reached a point of no return. He’ll die. Which means that just as this father-daughter relationship was about to get started, it’s already over. The End.

You would think ancient alien civilizations would be ripe subject matter for a movie. A sweeping shot of the long dead alien city alone is a money shot for your trailer. And yet the last two Alien movies proved that maybe ancient alien civilizations aren’t as cool as we thought they were. And this latest dive into the subject matter isn’t giving me a lot of confidence that that trend won’t continue.

Then again, Liu always seems to be more interested in the human element of these stories than he does the science element. If the character stuff works, it’s going to make the ancient civilization plot work by proxy. Unfortunately, the character stuff doesn’t work. Which is surprising considering that Liu wrote such a great parent-child storyline in The Paper Menagerie.

Today’s story proves that there’s a razor thin line between emotional effectiveness and melodrama. When the emotional component is working, it’s like magic. Our stories seem to come alive right from under our fingertips. When it’s not, it’s frustrating because you’re never completely sure why. It *should* work. A dad and the daughter he’s never met before are forced to team up to solve a puzzle. She doesn’t like him. He doesn’t understand her. The subtext writes itself.

However, something about this relationship feels on-the-nose compared to Menagerie and therefore never connects with the reader. I think I know why. If you look at The Paper Menagerie, the mother-son relationship was built around a very specific issue – she refused to speak English. He refused to speak Chinese. The story was about lack of communication. It was specific.

The Message doesn’t have that. There isn’t a specific problem in their relationship. It’s general. He ran off on his family so this is the first time they’re together. General is derived from the same tree as Generic. When you generalize in storytelling, you are often being generic. That’s what this felt like. Your average generic daddy who has to take care of a daughter he never knew he had story. Hollywood comes out with five of these a year. So if you don’t work to specify the relationship in some way, like Liu did with Paper Menagerie, the story is never going to take off.

More importantly, the emotional beats aren’t going to have the same oomph. This is why it’s so easy to shoot for a big emotional scene only to have the reader rolling their eyes.

Getting back to what Liu was talking about in that interview, he says that fictional writing should be all about the metaphors. I’m not sure I’ve heard an author say that before. I suppose it could be a short story thing. But I got the impression he was talking about all fiction. I vehemently disagree with that approach.

I got the sense that this ancient civilization had a metaphorical connection with the dad’s fractured relationship with his daughter. But I couldn’t make out what that connection was. Maybe someone can help me out. But even if I did understand the metaphor, it would not have made me connect with these characters any better. It would not have fixed the fact that the plot is basically two people walking around an empty city the entire time. Those are genuine story weaknesses that could’ve been improved if the focus was more on the storytelling and less focused on metaphor.

I’ll go to my grave saying that telling a good story should be the priority of every script you write. If you want to win new friends in your English class, go metaphor-crazy. But if you want to write a story that people actually enjoy, focus on the storytelling. Drama. Suspense. Irony. Unresolved Conflict. Problems. Goals. Obstacles. Stakes. Inner transformation. Urgency. And here’s the catch. You have to do all of these things IN A WAY THAT’S NOT DERIVATIVE. The story, along with the elements within the story, have to feel fresh and specific. The Message didn’t pass that test.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Work vs. Family is one of the most powerful character flaws available to writers. This is because it’s such a universal flaw that everyone understands. Even if you don’t yourself have the flaw, chances are there’s someone close to you who does. Which means you understand it. That’s what you’re looking for with character flaws. You’re trying to find flaws that all human beings can relate to. Here, the father chose work over raising his child. Liu didn’t nail the execution (in my opinion) but I still see this character flaw working in a lot of stories. I know writers often struggle to find a flaw for their main character. Well, this one is one of the easier flaws to show and execute as a character arc. So keep it in the hopper.

Titles are one of the most under-analyzed elements of screenwriting. That’s because titles don’t truly become important until the movie is being marketed. And since titles are only a few words, potential script buyers know they can easily change them. However, a good title can make a great first impression, getting a reader excited before they’ve even opened up your script. A *great* title can even get someone to greenlight a movie (as it famously did with the title, “Monster In Law”). So it’s worth carving out some time to come up with the best title possible. Here are a few all-timers…

Cool Hand Luke

No Country For Old Men

Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind

Slumdog Millionaire

The Devil Wears Prada

One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest

Things to Do In Denver When You’re Dead

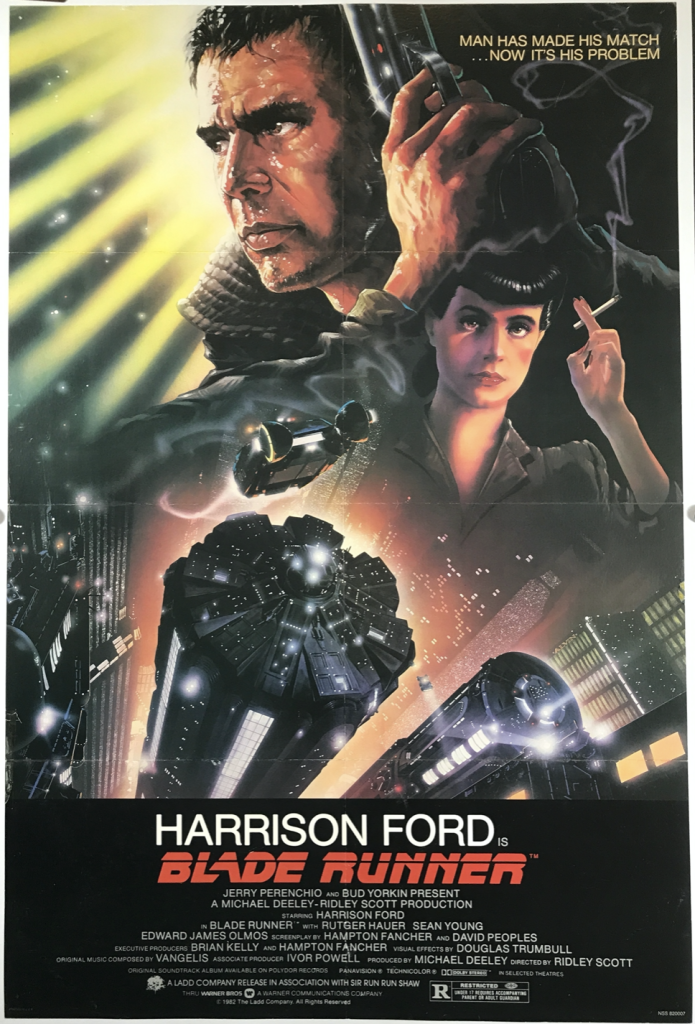

Blade Runner

Apocalypse Now

Kill Bill

Inception

Trainspotting

Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy

Full Metal Jacket

The Last Picture Show

Jaws

Back to the Future

Dude Where’s My Car

Midnight Cowboy

To Kill A Mockingbird

Touch of Evil

On that note, I’ve found that talking about titles in the abstract doesn’t do much for screenwriters. In order to understand what makes a title good or bad, you need to SEE the title. So what we’re going to do today is look at 25 titles from The Last Great Screenplay Contest and I’m going to give each of them a 1-10 rating, as well as some insight into how I came to that rating. I’m also going to include the genre because you can’t really get a feel for a title unless you know the genre.

By the way, if your title shows up here and I give it a poor rating, that has no bearing on whether I liked your script or not, as I’ve gone into every script so far only focused on the first 10 pages. Today’s article is about titles and titles only. Feel free to share your thoughts about each of these titles below and how you’d rank them. Let’s get to it!

Title: We’re Doing Just Fine

Genre: Black Comedy

Analysis: Solid title. It’s not going to win any awards but the combination of the genre and the irony of the title (“Just” conveys that they’re doing anything but fine) imply that the writer gets comedy. To see how this title could’ve gone south, look what happens when we give it a more straightforward treatment: “We Are Not Doing Fine.”

Rating: 7 out of 10

Title: Out of Time

Genre: Time Loop/Thriller/Action

Analysis: “Out of Time?” Really? Come on!!! A time loop thriller titled, “Out of Time?” You couldn’t come up with anything more original than that?

Rating: 2 out of 10

Title: The Commune

Genre: Contained Horror

Analysis: The problem with titles like this is that they imply you’re not tuned into the business you’re trying to break into. I think there have been a dozen movies titled, “The Commune.” I’ve probably personally read 20 scripts titled, “The Commune.” It’s a very very common title. It’s your job as a writer to know this because I guarantee you every industry person you send this title to is going to dismiss the script based on its generic nature.

Rating: 2 out of 10

Title: BIG TROUBLE IN BRECKENRIDGE

Genre: Action/Sci-Fi & Fantasy

Analysis: You want titles like this to have some contrast, some fun. Look at its inspiration: Big Trouble in Little China. See how much better that reads with the contrasting of the words “Big” and “Little?” Overall, the title inspires more of a visual than most of the titles today but it’s random and not very well thought out.

Rating: 5 out of 10

Title: The Good People

Genre: Horror

Analysis: A fairly decent title. Maybe a teensy bit too bland? But I could see this inspiring some reads with a good logline.

Rating: 6 out of 10

Title: Way

Genre: Drama/Romance/War/Historical/Action

Analysis: There’s information. There’s not enough information. And then there’s this. “Way?” This title literally feels like a mistake was made – that the writer was in a rush and mistakenly forgot to put the whole title in. Yikes.

Rating: 1 out of 10

Title: Candyflip

Genre: Drama/Thiller

Analysis: Easily one of the most original titles submitted. Gets you thinking. Wondering what the movie is about, which is good. I’m a little thrown by the “drama” tag. If this was a straight thriller or action movie, I think the title would work even better. But definitely one of the best on this list.

Rating: 8.5 out of 10

Title: When Tomorrow Starts Without Me

Genre: Thriller

Analysis: I like this one! It definitely gets you thinking, which is always good. Why would tomorrow start without our hero? There’s a mystery there I want to know the answer to.

Rating: 7 out of 10

Title: Tigers

Genre: Thriller

Analysis: I’m going to break my code and provide a little insight on this one. It’s got a really good premise and it made it into my “Maybe/High” pile. “Tigers” doesn’t tell us nearly enough about this story. It’s just too darn generic and doesn’t provide the level of curiosity a good script like this deserves.

Rating: 3 out of 10

Title: A Violent Noise

Genre: Drama/Action

Analysis: Too obvious. When you think “noise” you think loud, so a “violent” noise isn’t that far off. Which smacks of redundancy. Look for contrast in these types of titles. “A Violent Whisper” feels like a title I’ve heard before so I’m not claiming it’s amazing. But it’s definitely better than the on-the-nose “A Violent Noise.”

Rating: 4 out of 10

Title: The Arcanum

Genre: Fantasy/Action

Analysis: It’s a fantasy-sounding title. So I’ll give it that. But it loses points due to the fact that I have no idea what an “arcanum” is.

Rating: 5 out of 10

Title: Lotus

Genre: Psychological Thriller

Analysis: On the plus side, intriguing mysterious single-word titles can work. Especially in genres like horror, sci-fi, and psychological thriller. The trick is picking a word that is genuinely intriguing but also original. Hard to do. I think that’s where “Lotus” stumbles. It uses a word that has me intrigued. But I feel like I’ve seen too many titles like it before, which puts it in the good but not great category.

Rating: 6.5 out of 10

Title: Dark Lands

Genre: Action/Fantasy

Analysis: Easily up there with one of the most generic titles you can come up with for a fantasy film. Fantasy is one of the more imaginative genres out there. You need to give us a title that displays some level of that. Let’s get that imagination going, man. Not use something from Tolkien’s trash bin.

Rating: 2 out of 10

Title: Dolly

Genre: Horror

Analysis: One of the more effective things you can do with a title is to juxtapose it with your genre. That’s what we’re doing here. “Dolly” is a positive, almost jovial, word. So when it’s contrasted against horror, it creates intrigue. Conversely, if your horror script is titled, “Axe Murderer,” that’s pretty darn boring.

Rating: 7 out of 10

Title: Goodnight Nobody

Genre: Contained Thriller/Horror

Analysis: If we’re going on title alone, I’m not sure I get this. Maybe it’s a play on “Goodnight everybody?” I think that’s a phrase. But the turn-of-phrase doesn’t play off the original phrase organically enough to feel clever. – Now, I also happen to know that this script is about snakes. Why you have a script about snakes and don’t imply that anywhere in your title, I don’t know.

Rating: 3.5 out of 10

Title: Skin

Genre: Sci-Fi

Analysis: This is one of those rare occasions where the sparse, almost innocuous, title works perfectly in conjunction with the genre to imply something cool. Skin can imply so many things in the sci-fi genre, both literal and metaphorical. So I’d give this title a positive grade.

Rating: 7 out of 10

Title: Getaway

Genre: Horror/Thriller

Analysis: It’s not the worst title. The word “getaway” implies characters taking action, which is always good for movies. It creates an image in the reader’s head of what the movie is about. But I think I’d tell the writer, is this the best you can do? Yeah, it’s solid. But there’s definitely an unimaginative quality to it. Here’s a pro-tip for everyone. With movies, the title doesn’t have to be as splashy because it’s being displayed along with the trailer, or along with a billboard. So we have additional visual context to what the movie is about. With a script, you don’t have that. So it’s in your interest to come up with something that grabs the reader.

Rating: 5 out of 10

Title: The Little Friend

Genre: Horror

Analysis: This is one of the weaker titles I received. It doesn’t provide any working visual in my head of what the movie is. It actually achieves the opposite. It makes me think of weird things like a friend who’s 18 inches tall. If this was a comedy, that would work better. But it’s a horror film. And nothing about this title scares me. Make sure you’re thinking about the image your title is putting into the reader’s head.

Rating: 1 out of 10

Title: Hexagram

Genre: Action Horror, Supernatural Thriller, Contained

Analysis: Ahhhh! The dreaded triple-genre genre. Stay away from triple genres, people! Two at most! This title is just boring. I’ve come across hundreds just like it. Pentagram, Hexagram, Octagram. Well, maybe not Octagram. But you can be a lot more imaginative than using “Hexagram” as your title.

Rating: 2 out of 10

Title: The Player Agent

Genre: Sports/Biopic

Analysis: Something about this title reads weird. I want to put an apostrophe-s after “Player” so it reads, “The Player’s Agent.” I don’t know what a player agent is supposed to be. Like, he’s good with women and sports agenting? Is he an athlete and an agent? I suppose if that’s the case, it makes sense but no title should create this much confusion.

Rating: 4 out of 10

Title: Better

Genre: Psychological Thriller/Horror

Analysis: Too little info. There are simple one-word titles and then there are words that provide so little insight into the story, they’re pointless. But I have some good news for the writer, Rosario, so that this analysis goes down a little easier. Your script made it into the Maybe/High pile.

Rating: 4 out of 10

Title: Bring Me The Head of Harvey Valentine

Genre: Action/Adventure

Analysis: One of the few titles I’ve received that really goes for it. It wants to make a statement with its title and I like that. It’s one of the more memorable titles I received. My only pushback would be that it’s not that original. I’ve come across that phrase enough that it doesn’t do a lot for me. Even the name is unoriginal. Had the name been something more outlandish, that would’ve helped the title a lot.

Rating: 5.5 out of 10

Title: Almost Airtight

Genre: Horror

Logline: I would avoid using words like “Almost” in your title for anything other than comedy scripts. The word has a flimsy implication and therefore doesn’t line up with horror. Words like “Maybe,” “Almost,” “Basically,” – these are comedy title words.

Rating: 4 out of 10

Title: Do Us Part

Genre: Rom-Com

Analysis. Obviously, we’re playing off the phrase, “Til Death Do Us Part,” but not in a way that’s clear. It took me a coupe of reads to understand it. This feels like one of those situations where the writer is trying to be too clever by half.

Rating: 3 out of 10

Title: Get Woke

Genre: Buddy Comedy

Analysis: Anything that makes fun of a current public ideology is ripe for a comedy title. The trick with comedy titles is that, while they don’t need to make you laugh, they need to imply a world where you can imagine laughing a lot. Which this title does.

Rating: 7 out of 10

Now that we have our 25 titles, let’s rank them. Yes, I know these don’t perfectly reflect my ratings but this is how I ranked them from memory. From worst to best!

25 – The Little Friend

24 – Hexagram

23 – Dark Lands

22 – Way

21 – The Commune

20 – Out of Time

19 – A Violent Noise

18 – Tigers

17 – Better

16 – Goodnight Nobody

15 – The Player Agent

14 – Getaway

13 – Do Us Part

12 – Arkanum

11 – Big Trouble in Breckenridge

10 – Almost Airtight

9 – Bring Me The Head of Harvey Valentine

8 – Get Woke

7 – Dolly

6 – Skin

5 – Lotus

4 – When Tomorrow Starts Without Me

3 – We’re Doing Just Fine

2 – The Good People

1 – Candyflip

Is this the best sci-fi fantasy short story ever written?

Genre: Short Story – Drama/Fantasy

Premise: A young half-Chinese half-American boy struggles to connect with his Chinese mother, who doesn’t speak English.

About: This is a multiple award-winning short story by Ken Liu from his short story collection, “The Paper Menagerie and Other Stories.” You can find it on Amazon. I don’t think the short story can be found anywhere online, unfortunately.

Writer: Ken Liu

Details: Around 4000-5000 words

Ken Liu is really starting to blow up. The team that made 2018’s, “The Arrival,” is turning one of his short stories, “The Message,” about an alien archaeologist who studies extinct civilizations and reunites with a daughter he never knew he had, into a film. AMC is developing a series based on his short stories called Pantheon. You also have Game of Thrones creators David Benioff and D.B. Weiss, adapting Ken Liu’s English translation of the epic sci-fi novel, “The Three Body Problem,” (which won the 2015 Hugo Award for Best Novel, making it the first translated novel to have won the award) for Netflix.

When I started looking into Liu, I learned that his big blow-up moment came upon the release of the short story, The Paper Menagerie. That story achieved something that had never been done before, which is sweep the Hugo, Nebula and World Fantasy writing awards. Everybody says this short story is amazing.

Which has inspired a secondary question as I go into this review. If this is his best work, why isn’t anyone trying to adapt it? There might be an obvious answer to this by the time I finish (some stories just aren’t easy to adapt) or, if not, maybe this article will be the impetus for someone finally buying it.

With that in mind, let’s do this!

(by the way, this story is best enjoyed without knowing anything so I’d suggest reading it first if possible)

Jack is a young boy who lives in Connecticut with his American father and Chinese mother. Jack informs us right away that his father found his mom “in a catalog” for Chinese women looking for American husbands. Even at this young age, Jack considers this weird and something to be ashamed of.

Because his mother was a Chinese peasant, she doesn’t know any English. She tries. But the words never come out right and she becomes embarrassed. Because his father makes him, Jack learns Mandarin, but he resents that his mother isn’t trying harder to learn English, and therefore refuses to speak her native tongue.

However, Jack’s mother finds another way to communicate with her son. One of the skills she learned from her village was creating special origami animals that are alive!

His family, being poor, couldn’t afford the fancy toys at the time (like all the Star Wars figures) so these origami animals became his toys. He would play with them for hours in his room, never tiring of them.

But when he became a teenager, his resentment for his mother skyrocketed. All this time and she still hadn’t properly learned English, meaning she couldn’t have a conversation with anyone, even her own son. Jack began talking to his mom less and less and even boxed away all her origami animals and threw them in the attic.

During his college application process, his mom gets sick. Her insistence to not be a bother to anyone had meant, by the time she checked in with a doctor, her cancer had spread too far to be treated. Even at this moment, Jack could not muster up any emotion for his mother. Here he was about to pick a college and his mom was still finding a way to mess it up. When he goes out to school in California, his mother dies.

Years later, Jack’s girlfriend finds his old box of origami animals and after she leaves for the day they, once again, come alive. Jack plays with them and it’s just like he was a kid again. Then he spots something on his favorite animal. As he unfolds it, he realize his mother has written a note inside. But it’s in Chinese. So Jack goes to someone who can translate it for him, and the woman reads his mother’s letter to Jack, which tells him the full story of her devastating childhood and how her life was meaningless until he showed up in it.

Okay.

I challenge anyone to read this story and not start bawling from the get-go. This is the saddest story ever. But good sad. “Gets to the heart of broken mother-son relationship” good sad.

I read a lot of screenplays that try to make you cry. Rarely do they achieve it. People think all you need to do to make a reader cry is give someone cancer. Have them die before ever saying “I love you” and people will eat it up. Making people cry is surprisingly difficult. There’s something about the act of trying to make someone cry that keeps them from crying. It’s almost like they know what you’re up to. For emotion to hit on that level, it has to feel like real life. Not like a writer trying to manipulate your emotions.

But one thread that seems to be present in a lot of cry movies is an unresolved family relationship. It could be a man and his wife, a father and daughter, a sister and brother, or, in this case, a mother and son.

I’m not going to pretend like I know the exact code for why this worked because I think nailing an emotionally brilliant story is always going to be a “lightning in a bottle” scenario. But I found it interesting that Liu reversed the typical roles in this kind of story. Instead of the parent being the one who disassociates from the child, it’s the child who pulls away from the parent. And for, whatever reason, that’s more heartbreaking. A child isn’t supposed to despise his mother.

That’s also a big reason why we’re turning the pages. Whenever you set up an unresolved scenario between two characters, we’re naturally going to want that relationship to be mended. It’s painful to walk away from something this emotionally powerful without knowing how it ends. Just by setting this scenario up, you’ve ensured that we’re going to read the full story.

But where Paper Menagerie separates itself from the 10 million other stories that have also tried and failed to make you weep, is this “strange attractor” in the origami animals. The story isn’t just mom and son arguing every day, which is the typical scenario I encounter in similar setups. The mom speaks to Jack through the animals. They become the only way the two communicate. And that adds a special element that elevates the story.

Another small detail was the meanness of Jack. Now, normally, you don’t want your main character to be mean. Once you cross a certain threshold of un-likability for your protagonist, the reader dislikes them and no longer cares about their journey.

What this does is it scares writers into always writing nice protagonists. The problem with that is that there’s nobody on the planet who’s perfect. We’re all flawed. We all have unpopular opinions. Mean thoughts. And if you take that arena away from your hero, you also take away their truth. You are now constructing something that doesn’t exist. And readers pick up on that.

The reason why it works here is because WE UNDERSTAND WHY JACK FEELS THIS WAY. That’s the key to making “mean” protagonists work. As long as we understand where their anger or meanness comes from, or, even better, we can relate to it in some way, then the meanness is going to work.

Jack is lonely. He is half-Chinese in a town where there are no other Chinese kids. Everyone knows his mom was purchased. When friends come over, his mom never speaks because she doesn’t know English. As a kid, this is embarrassing. Cause you have to deal with the effects of that every day. Of course you’re going to have resentment towards your mother. Once you’ve grounded the central story emotions in that reality, you’re golden. Because now we believe what we’re reading to be true and our focus shifts to, “Will this broken bridge ever be mended?”

Finally, I want to talk about the big final letter. The “final letter” scenario is actually something I see quite a bit in screenplays. Everyone thinks they’re being original when they do it but, trust me, it’s not original. And most of these writers fail gloriously with these letters. The reason being that they write something too obvious. “I always loved you. I think you’re going to become an amazing person. I wish we could’ve been closer but I’ve learned with time we will always be together spiritually… blah blah blah.”

This letter hit on some of those things, but it wrapped them around two key choices that elevated the letter beyond your typical “end of movie letter moment.” The first was she told the story of her childhood. Again, most writers are thinking literally: “I need to have mother tell son how she feels.” That’s obvious and rarely works. So to instead talk about her childhood shifts the focus away from her feelings about him and tells us about her. It was unexpected and her background was so detailed and interesting that it was almost like a story in itself we wanted to know the ending to.

The second thing Liu does (spoiler) is that the letter doesn’t end on a happy note. It isn’t one of those, “Go out there and seize the day!” endings. It’s more of a, “I was devastated we could never communicate and I always wished you gave me more of a chance” endings. That simple shift takes this from a perfect wrapped–in-a-bow Hollywood ending to something more realistic, more true to life.

I see now why everyone went nuts for this. It’s almost a perfect story. I don’t think they can turn it into a movie though. It works because its short form allows it to stay hyper-focused on the relevant variables (the mom, the origami animals). Once you extrapolate that and add a bunch of other plot, the concept becomes distilled and the animals don’t make as much sense.

I don’t know. Maybe someone would be able to figure it out. I’m surprised no one’s tried. Like I said earlier, maybe they will now.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[x] genius

What I learned: Ken Liu has an interesting philosophy in how he treats his first draft. He calls it the “Negative First Draft.” Here is his explanation to tor.com. – I usually start with what I call the negative-first draft. This is the draft where I’m just getting the story down on the page. There are continuity errors, the emotional conflict is a mess, characters are inconsistent, etc. etc. I don’t care. I just need to get the mess in my head down on the page and figure it out.The editing pass to go from the negative-first draft to the zeroth draft is where I focus on the emotional core of the story. I try to figure out what is the core of the story, and pare away all that’s irrelevant. I still don’t care much about the plot and other issues at this stage.

The pass to go from zeroth to first draft is where the “magic” happens — this is where the plot is sorted out, characters are defined, thematic echoes and parallels sharpened, etc. etc. This is basically my favorite stage because now that the emotional core is in place, I can focus on building the narrative machine around it.