Search Results for: It

Today we take on the genre YOU SHOULD BE FOCUSING ON if making money is your priority as a screenwriter.

Genre: True Crime

Premise: Set in 1981, a serial killer kidnaps his latest victim, who proceeds to use religion to convince him that he is not the killer he has accepted himself to be.

About: Huge bidding war for this one that Amazon/MGM just won. It was an article in Vanity Fair. Stephen Morin’s killings are mostly forgotten over time due to several reasons, one of them being that the victim in this story, Margy Palm, wasn’t interested in selling the rights to her story to Hollywood, who she felt would turn it into some cheap surface-level story about the power of God. Only recently having gone through therapy, Palm has come to the conclusion that it’s finally time that her story be told.

Writer: Julie Miller

Details: About 6000 words long (the length of 4 Scriptshadow posts)

Sydney Sweeney is perrrrrrfect for this role.

Sydney Sweeney is perrrrrrfect for this role.

What is it that Jerry Maguire said on that fateful day of his firing?

Oh yeah.

SHOWWWW MEEEE THE MONAAAAAAAYYYY!!!

Ever since the spec boom ended, screenwriters have been looking for a substitute source of instant income, a way where they could write something and get paid for it immediately. Well, my friends, that something is here. It’s called True Crime.

True Crime has always sold. Heck, they were making these things as TV movies all the way back in the 70s. But ever since podcasts supercharged the genre, True Crime has become more marketable than ever.

From The Watcher to Dirty John to Love & Death to The Staircase to The Act to Mindhunter to Dahmer. And now you have this whole new sub-genre of shows inspired by true crime, like Only Murders in the Building, Based on a True Story, and The Afterparty.

Without mincing words, you have to be more into television than movies if you want to sell one of these things. But it actually doesn’t matter because, in order to sell them, you’re going to write an article first. Whoever then buys the article will decide if they want to turn it into a movie or a TV show.

“True Crime: True Faith,” set in Texas in 1981, introduces us to Stephen Morin, a serial killer who seems to have escaped mainstream attention due to the fact that he was killing at the same time as the much flashier hipper serial killer, Ted Bunny.

Morin targets a young pretty blonde wife named Margy Palm, who’s returning to her car from K-Mart after doing some Christmas shopping. At this point, Morin had raped and killed dozens of women, something Palm wasn’t yet aware of. But she knew once he took her hostage that he was an angry dangerous man.

And yet, as he made her drive outside of San Antonio to a more secluded area to do who knows what with her, Palm didn’t feel afraid. A religious woman, she began explaining to Morin that he had the devil inside of him and during the many times when they’d park (Morin would get hungry, for example, and randomly head to some fast food restaurant) she would attempt to cast the demons out of his head.

At first, Morin was furious that he’d been stuck with some “religious freak.” But the more Palm spoke about God, the more sense it made to the killer. Palm busted out some scripture for Morin to read and soon, the two were sharing deep intense experiences from their pasts, bonding on a level that even Palm admits, to this day, she had never experienced before.

After 8 hours of driving around, Palm had successfully converted Morin into a born-again Christian. His lifelong anger had all but evaporated. She told him that there was a preacher he needed to visit in another part of Texas and took Morin to the train station so he could go to this man and confess his sins. She gave him her scripture and off he went. The police were waiting for him at the station where he was still reading the scripture.

Morin would later go on to receive three life sentences and the death penalty. But Morin started to call Palm from prison and, unthinkably, the two became friends. Palm would come to see him 15 times over the next four years and visited him a day before his execution. Morin called those last four years the best four years of his life because he found God.

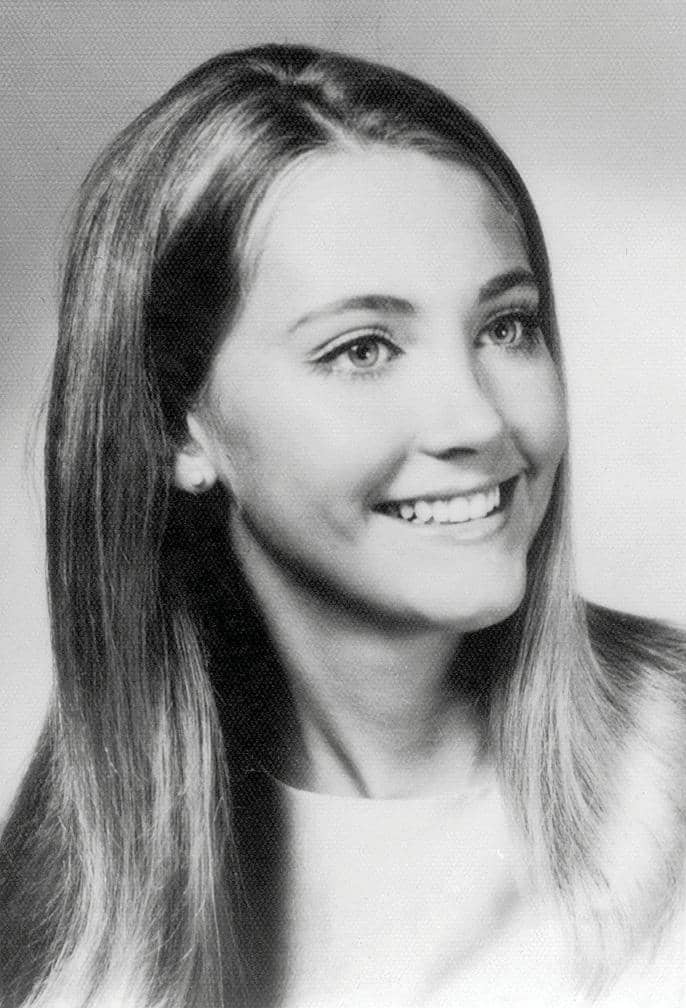

The real Margy Palm

The real Margy Palm

Time to start writing some true crime articles, right!

I know some of you are like, “ehhh, I don’t know. I just want to write scripts, Carson. I don’t want to write short stories or articles or any of that nonsense.” I get it. We writers are creatures of habit. But let me say this. One of the things I would’ve changed when I was a young screenwriter was not being so stubborn. I thought I knew how to do it and I was only going to do it that way. I know that if I was more open to other ideas and trying new things, my path would’ve been different.

There’s a reason these articles are selling beyond them being true crime. Much like short stories, they’re easily digestible to busy industry people. Which means that when agents send these packages out, people are more willing to read them because the time investment is much smaller.

So, how do you find a good true crime story to write about?

It’s not that different from looking for any concept. You’re looking for fresh angles that haven’t been explored yet. You’re looking for interesting characters, meaty parts that actors would want to play. And as I tell you all the time, you’ve discovered a gold mine if the true crime story has some element of irony to it.

One particular sentence stuck out to me in this article. “I became friends with a serial killer.” Take a good long look at the line. That line is the face of irony. You’re not supposed to be friends with a serial killer. Serial killers are evil. Especially ones who wanted to kill you. And yet that’s the primary relationship here – one where this offbeat friendship emerges from the most unlikely of circumstances.

I can imagine how they might adapt this into a TV show. You start off with this scene in prison where Palm has come to visit Morin. We don’t know who these people are yet or the context under which they know each other. But they’re laughing. They’re having a good time. And then we smash-cut back to that fateful day where he grabs her in the parking lot and forces her into the car.

You could have a lot of fun juxtaposing those two worlds. And, actually, you could write this as a movie as well, if you wanted. Any time you see a tight timeframe, that’s ideal for a film. That 8 hours that Morin kidnaps Palm for… that’s a perfect timeframe for a movie, especially if you could convince us that she really was in danger and that he’s going to kill her.

But this one comes back to the characters. Good memorable characters are sooooooooo hard to write. They’re so hard to write. It amazes me whenever one shows up in a movie. And it shocks me when one shows up in a screenplay, where you’re even less likely to run into well-written characters.

Morin goes through this clear arc as a character that is perfect for a story. But he’s also volatile. The article points out that one second he’s sharing his biggest regrets to Palm and the next he’s screaming at her for being rich and having a perfect life. Then you have Palm, who’s the perfect underdog. She’s the overmatched girl who should die just like the 30 girls before her. But she’s ACTIVE and takes a different tactic than you’re supposed to take. And it ends up working and… who’s not going to root for that character?

Also, the same rule for storytelling applies today as it did 100 years ago: If you have at least one dead body, you’ve got yourself a story.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[xx] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: So many writers revert to guns and violence for their characters to solve problems. But I promise you that it is ALWAYS more satisfying to the audience and to the reader if the character OUTWITS their opponent. That’s what this story is about. It’s about a woman who outthinks her captor.

Today, Thursday, is the last day to send in your logline for the Halloween Logline Showdown. If you have a great horror script, get that logline in! I’m determined to find a great horror screenplay before this Halloween month is over.

What: Halloween Logline Showdown

Send me: Logline for either your Horror or Thriller script (Pilot scripts are okay!)

I need: The title, genre, and logline

Also: Your script must be written because I’ll be reviewing the winning entry the following week

When: Deadline is Thursday, October 19th, by 10:00pm Pacific Time

Send entries to: carsonreeves3@gmail.com

So what will I be looking for when I review the winning horror script next week?

To answer that question, we need to understand why writing a horror script is so tricky. Horror is one of those genres that’s primarily director-driven. Case in point, when was the last time you heard of a great horror screenwriter? Yet you know the names of John Carpenter, Wes Craven, James Wan, George Romeo, and the list goes on. The only horror screenwriters you’ve heard of are the ones who direct.

I’m not trying to scare you. I’m only saying that writing a good horror script is a bit like cooking a pizza. We all know what makes a good pizza. Great crust, lots of cheese, a delicious tomato sauce. And yet when we try to make pizza, it’s a far cry from what we eat at the restaurant.

So what I thought I’d do is provide you with the ten things that I find most important in a horror script, starting with the most important and ending with the least important. Let’s get into it.

One – It’s got to have three scary-AF scenes – Nothing else matters in your horror script if it’s not scary. And the place you scare people the most is in your set pieces – the big featured scenes in your script. I’m talking about the girl emerging from the well in The Ring, the “Do you like scary movies” opening scene from Scream, the sister decapitation from Hereditary. You need three of these in your horror script. These are so important that even if you have a terrible screenplay, there’s a good chance that by including these three great horror scenes, someone will want to make your movie. Because a truly scary scene can live on forever regardless of the quality of the movie (see the hospital scene in Exorcist 3). Producers know this. So use all your time to come up with these scenes.

Two – This is an extension of number one. You must draw your scares from what’s unique about your script. One of the biggest problems with horror movies is that they’re all cliche. Everybody uses the same ten scares (creepy dream sequence, someone behind you in the bathroom mirror, the injured woman running away from the killer, etc). The best way to avoid this is to utilize what’s unique about your concept because those scenes are less likely to be in other people’s horror films. A great example of this is the foot-breaking scene in Misery. Annie is obsessed with this man. She’s imprisoned him in her house. He tries to escape. So, in order to make sure he doesn’t try again, she violently breaks his feet with a hammer. That scene is very specific to that situation. Whereas, if you’re writing a cat jumping out of a cabinet, that’s a scene that can literally be in any horror movie. If your horror scene could be in any horror movie, DON’T INCLUDE IT!!!

Three – Strong Characters – I’m going to drop a controversial Carson-bomb here. But I think character development in horror films can go too far. The Babadook is a good example. I liked The Babadook. It’s a solid movie. But it places so much emphasis on character development that it ends up overshadowing the horror. That movie is 70% drama and 30% horror. Whereas a good horror movie should be 70% horror and 30% drama. With that said, too many writers make the mistake of putting nothing into their horror characters. This is a script-destroying move because if your horror characters are too thin, we won’t be afraid for them when they’re in scary situations. And having the audience care for your characters when they’re in danger is the whole ball of wax when it comes to horror. The reason horror works is because we sympathize with the characters! Therefore, when they’re in danger, we feel like we’re in danger. So make sure we like the characters, we care about them, they’re going through something internally (struggling with self-acceptance, for example) as well as externally (they’re getting bullied at school). They have some sort of unresolved relationship with another character. And that’s it. Keep it simple.

Four – A killer (terrifying) monster/villain – For a lot of horror films, the monster is the concept (Mama, Freddy Kreuger, Pennywise, Slotherhouse). So you want to spend a significant amount of time coming up with your monster. Not to mention, a great monster takes care of the marketing all by himself. Just look at The Nun. All you have to do is put the Nun’s face on a poster and you’re finished. To find your horror script’s monster, I suggest you look to the past. Look up monsters and scary stories from all parts of the world throughout time and you’ll find some really gnarly things. I’ve found that building your horror monster from the ground up (figure out their past and let it inform their present) works better than trying to come up with a scary image (a clown with no eyes) then trying to retroactively shape their origin. But that’s just me.

Five – Be shocking – This is a bit controversial as I know not everyone will agree with me. But I read enough scripts to know that if you don’t do anything above and beyond the usual, it’s likely your script will be forgotten. And with horror, the way to be remembered is to be shocking. As someone brought up the other day, the girl in The Exorcist has a scene where she stabs herself in the vagina with a crucifix. How do you not leave that script never forgetting that moment? And if you doubt that, ask yourself, who is the most talked about horror director at the moment? It’s Ari Aster. And that’s Ari’s whole strategy. He shocks you. Look up his first short film if you don’t believe me. To shock readers, you have to be willing to write about things that make you uncomfortable. But I promise you if you shock us, as long as it’s organic to your story, you’re going to leave an impression.

Six – A unique setting – Again, what you have to remember is that horror is the most ubiquitous genre there is. You’re competing against more scripts than in any other genre by far. So you need to look for any way you can to separate your script from their scripts. The setting is a great way to do this. Because if you can come up with a unique setting, you won’t be operating in the same locations and situations as all the writers before you, which will give you new avenues to find unique scares. “The Thing” is a great example of this. It’s not set in a cabin in the woods like 10 million other horror scripts. It’s set on a remote base in Antarctica. That immediately gives it opportunities to find fresh scares.

Seven – Effort – You might be noticing a theme here. Horror scripts get swallowed up in cliche for a number of reasons. To combat this, you need to exhibit outsized effort when venturing into this genre, something very few writers do. You are not going to be able to zip through the writing process of a horror script and write something good. I guarantee your script will be littered with cliches if you do. You need 7, 8, 9, 10 drafts to weed out all the familiar stuff and add those deeper more imaginative ideas that come from having a high bar and pushing your creative limits. You should be treating your horror script like Martin Scorsese treated his Killers of the Flower Moon script. He did not stop rewriting until he found something he liked.

Eight – Build tension slowly – A lot of great horror does not come from the act of the [scary thing] jumping out at you. It comes from the build-up to that moment. So, when it’s applicable, cue the reader that a scary moment is coming then draw out the lead-up to that scare for as long as possible. If there’s something in the corner of the dark bedroom, for example, don’t have it scurry over right away. Have your character try to make out its features, unsure of it’s a monster or just clothing, have them turn on their lamp only to see that there’s nothing there. Have them turn the lamp back off and turn over to go to sleep. But then they hear a skittering and shoot back up, looking around. There, in the other corner… is that a body? Are my eyes playing tricks on me ? You get the idea. The lead-up is what super-charges the scare.

Nine – Concept is nice, but not essential – In my experience, a horror script does not have to have a great concept. This is because horror is the only example where the genre itself is the concept. People come to horror movies to be scared. So as long as your trailer looks scary, you’re good. A scary nun. A scary doll. A haunted house. An invisible evil husband. Taking your boyfriend home to meet the weird parents. A girl is possessed. A spooky entity follows you around. Zombies. More zombies. Lots and lots of zombies. This is not to say a clever horror concept (The Sixth Sense) is bad. Quite the opposite. If you can come up with a great concept in the horror genre, you’re unstoppable. But you don’t NEED a great concept to write a good horror script.

Ten – Plot don’t matter as much as you think it does – I want to be clear when I say, you would like to have a solid plot in your horror script. But it’s not mandatory. We know this because nobody has ever watched a horror film in their lives and come out saying, “Man, I loved that plot.” It’s just not a part of the genre’s lexicon. I told you last year when I watched Friday the 13th for the first time in two decades how shocked I was at the lack of any noticeable structure. It was just a barely-cobbled together string of scenes where a killer tried to kill teenagers at a camp. And that went on to become a half a billion dollar franchise. Again, if you have a great plot – AWESOME. It’s only going to help your horror screenplay. But you should be spending more of your time on scary set pieces and likable characters than an amazing plot.

DEALS DEALS DEALS! – I’m offering a $150 discount on both my feature script consultations and pilot script consultations. I’m also offering a 3-pack of logline consultations for just $50! If you’re interested, e-mail me at carsonreeves1@gmail.com and mention this article!

You have to give it to Hollywood.

The town does have a sense of humor.

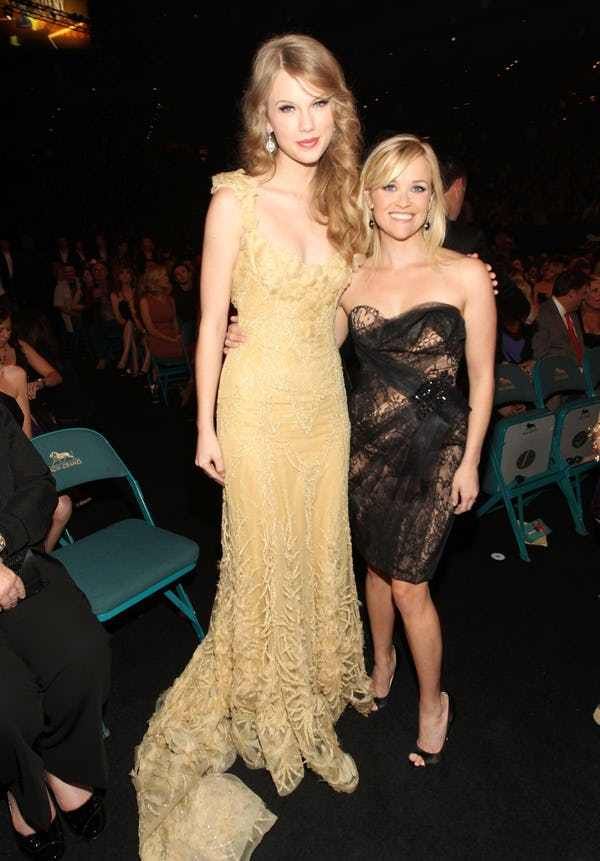

I mean why else would you plop a Taylor Swift concert movie right in the middle of Horror Season?

The tall gangly crooner does possess a certain “Ichabod Crane” quality, which may have been the secret sauce to getting her film to 100 million dollars. People showed up, fully expecting a Conjuring-like experience. And some of them got it. Looking at 50,000 Swifties blathering through tears is scarier than anything I saw in The Exorcist. But most were like, “Wait, this woman is just singing for 2 hours?”

But in all seriousness, the gigantic haul of Taylor Swift’s film, when seen through the lens of a year that also celebrated Barbie’s titanic box office, has begged the question: Is it time we start writing more for female audiences?

It used to be that men generated all the box office. Young men in particular. Then the post-Bridesmaids era combined with the #metoo movement demanded the industry focus more on female-centric films. They did, to mixed results, but certain films (Captain Marvel, Wonder Woman) proved that the ladies liked to show up. But those were films that catered to both men and women.

This 1-2 Barbie-Swiftie punch has rewritten the box office code. Now, you can make movies for JUST WOMEN and still eclipse 9 figures.

So, this means write movies only for women, right?

Ehhhhhh, let’s dial back the estrogen on that one. The Marvels, a movie designed not just to attract women, but to actively repel men, is coming out on November 10, and its box office tracking is placing it at as the lowest Marvel movie opening ever, less than The Incredible Hulk. Unless they can figure out a last second way to give Slenderman, err, I mean Taylor Swift, a cameo in the film, it’s gearing up to sink the comic book studio faster than the Andrea Doria.

As Taylor Swift would say, “I’m not that… innocent.”

Taylor said that, right?

While the Taylor Swift movie may have been too scary for me, I did want to check out a festive movie this weekend so I went with Poe’s suggestion and fired up, “Totally Killer,” on Amazon.

The film, a slasher version of “Back to the Future,” focuses on Jamie, a high school student whose mother is murdered by the Sweet 16 Killer, a notorious masked serial killer who, 35 years ago, killed 3 teenage girls.

Jamie utilizes the help of her nerdy friend who happens to have built a time machine to travel back to the year 1987. She figures if she can identify and take out the serial killer, she can not only save those three girls, but she can save her mom.

Along the way, she runs into her 16 year old mother, who turns out to be a total bizatch. She’ll have to team up with her, though, to stop the murders. But the other girls are so incredibly stupid that they practically walk into their deaths, no matter what Jamie does. Still, if she can identify the killer, she can hopefully stop the death of her mom.

I can promise you this. Totally Killer was a lot better than the Jack Skellington biopic at theaters this weekend. I mean the Taylor Swift movie.

The movie had a surprisingly edgy sense of humor. There’s a subplot with a couple of dopey 80s cops who do nothing but hang around and chat. Our introduction to them has us eavesdropping on their first conversation: “Old people, sick people, and people with dogs.” There’s a pause and the other cop says, “That’s the order you hate people in?” “Yep.” Not gonna lie. I LOL’d hard.

And conceptually, it’s kind of perfect. Something I’ve told you guys from the get-go is that every screenwriter gets into the game to rewrite their favorite movies. The mistake they all make is that they literally rewrite their favorite movies. So there’s no originality. And the script looks like a big fat ripoff.

Totally Killer shows you the way around this. You take your favorite movie and you move it into another genre. Here, we obviously have Back to the Future. But the writers frame it within the slasher genre. This allows them to copy a lot of the BTTF beats without looking like copycats.

But even beyond that, it’s a surprisingly effective combination. One of the many genius aspects of Back to the Future was how quickly it moved. I’ve found that whenever anyone tries to copy the movie (Peggy Sue Got Married) or replicate that same Michael J. Fox energy (Teen Wolf), the movies just sit there. It shows you just how hard it is to keep the pace up in any plot.

By adding a slasher element to the blueprint, Totally Killer’s plot hits the ground running. The second Jamie ends up in 1987, she’s got to prevent three murders from happening. I thought the writers did a really good job with that.

The movie only has two faults, one small and one big. I thought it could’ve leaned more into the offensive world of the 1980s. It would be a TOTAL SHOCK for a 16 year old girl from 2023 to go to school in 1987. Every safe space she knew would’ve exploded in front of her. And while Totally Killer does some of that (a boy shoves Jamie by the chest as she loudly declares, “Unwanted touch! Unwanted touch!” And the guy doesn’t care nor does anyone sympathize with her), I always say that you need to wring every last drop out of what’s unique about your concept, especially with fish-out-of-water scenarios. Let’s have some TRULY offensive 1980s things happen here.

The bigger issue is one that keeps this from being a classic, and that’s the main actress. She wasn’t right for the role. She’s too dour. Too restrained. Too low-key. Too sarcastic. There’s a reason Back to the Future is one of the top 20 movies of all time. It’s how charming the main actor is.

Totally Killer is kind of like seeing how Back to the Future would’ve played had they kept Eric Stoltz in the lead. The actress, Kiernan Shipka, is meant for more serious rolls. I mean you can see flashes of this being a great film if they had only cast a more charming actress, although now that I’m thinking about it, the female equivalent of Michael J. Fox may not exist. Heck, they haven’t been able to find an equivalent for Michael J. Fox on the guy’s side either.

But if we’re keeping score for the feel-good horror movie of the 2023 Halloween season, Totally Killer gets my vote.

Before we wrap up today’s ode to Peter Cushing, I mean Taylor Swift, I have to exit with a gripe. Rotten Tomatoes needs to place new rules on their horror scoring. There is no other genre they get wrong more than horror. And it’s usually WAAAAAAY over-praising horror content.

After Totally Killer, I was in a good mood. I wanted to pop in another fun horror movie or show, something that could both spook and spike my funny bone. I kept seeing ads for Chucky, the TV show adaptation of the 1980s cult classic, Child’s Play. What caught my eye was the out-of-this-world Rotten Tomatoes scores. We’re talking above 90% for all three seasons!

I thought, this show can’t possibly be that good. But I gave it a chance anyway cause why not. My friends, I watched the pilot for this show. I know certain animals that could’ve directed a better episode of television. It’s not that the show was bad. It’s that it was LIFELESS. From the casting to the production value to the acting to the scene-writing. It was soooooooo so so so so so so boring.

I was unexpectedly pissed that I’d been tricked so badly, since I knew I smelled a rat from the start. I just have to remember that it doesn’t matter what kind of score a show gets. IF IT IS NEVER TRENDING ON SOCIAL MEDIA and IF NO ONE ON THE INTERNET IS WRITING ABOUT IT, it’s bad. That’s all you need to know. I had never seen Chucky mentioned once on social media and I’d never seen anybody write about it. From now on, that’s my gauge for whether to check out a show. I suggest it be yours as well.

Okay, did anybody see the Stephen Merchant film this weekend? I mean Taylor Swift film? What did you think?

I stumbled across this video recently while performing a most impressive act of procrastination. I was half-listening at first but as Gervais’s calm soothing British tone gesticulated across me, I found myself subconsciously nodding. I restarted the video and listened more closely.

I’m convinced that what Gervais says here is the single most important factor to writing things that people care about. So much so, I would argue that nobody reading this article today can become a professional writer until they go through this transformation of understanding. They have to accept it, understand it, then execute it, so they can graduate to the other side.

To give you the TLDR of the video, Gervais says that he started out writing fun silly stuff – cop movies where the cop “didn’t play by the rules.” And whenever he turned these scripts into his teacher, the teacher would tell him, “This isn’t any good. Write what you know.”

But Gervais was convinced that people didn’t care about boring truthful everyday stuff. He wanted the fun stuff. The stuff that’s on TV. The stuff he saw in the movies. So he kept writing what he wanted. And he kept getting bad grades.

Finally, he figured he’d pull a fast one on the teacher. As it so happened, every day, his mother would go next door to take care of an elderly woman and sometimes Ricky would go with her. It was the single most boring thing you could write about, in Gervais’s opinion. But it was something “that he knew.”

So he wrote about a day following his mom over to this elderly woman’s house. And he went into excruciating detail. He wanted to make sure that he was writing EVERY SINGLE THING HE KNEW about this experience in order to prove to his teacher that the teacher was wrong and that writing about this sort of thing only led to boring people to death.

I think you know where this is going. When he got the grade back, he’d received his first A. And that’s when the lightbulb went on for Gervais. It isn’t about all the fantastical larger-than-life craziness. It’s about humans connecting with other humans. You achieve this by writing what you know. And because you’re writing what you know, you are writing THE TRUTH. And THE TRUTH is the single most important part of getting readers to connect with your writing.

This isn’t the first time I’ve heard a writer share this story. I hear a lot of writers say this was the moment they finally understood writing. Neil Gaiman talks about how nobody cared about his writing until he started “telling the truth.”

But what is “the truth?” What does “the truth” look like?

It starts with, like Gervais says, “What you know.” For there is nothing you know more truthfully than your own life.

I used to teach tennis, as some of you know. So let’s use that as our theoretical backdrop. We’ve got Writer 1, who took a couple of tennis lessons when he was a kid and wants to write a movie about a tennis pro. Then we’ve got Writer 2, who taught tennis for ten years, and wants to write a similar movie (me).

The first scene of Writer 1’s movie is probably going to be our tennis pro showing up at the Beverly Hills Country Club or a similar upscale tennis place. He’s got his tennis whites. He’s got a 5 o’clock shadow. He makes some funny quips to a few co-workers, as well as the hottie tennis pro he’s dating. She asks if they’re still having lunch later. Of course. He rushes out to teach his first lesson, a sexy MILF who’s giving him googly eyes the second he steps on the court. He tries to teach her but she can’t help but make a bunch of sexual innuendos during the lesson. Afterwards, she proposes that all future lessons take place at her private tennis court. He has to practically slip out of her grip to get away from her. And that’s the first scene.

Now, let me tell what a morning with me was like as a tennis pro.

I would ride my bike to work because my car was always broken. I had timed it so I got to work at exactly 8am. That way I could technically say that I was on time, even though it would take me another five minutes before I got on the court and started my lesson, to a client who was in no way interested in or trying to flirt with me. They were just mad because their lesson was going to start late.

Now, I didn’t teach at Beverly Hills. I taught at Westwood Tennis. A park. Which meant that I would have to wake up the homeless person sleeping in front of the tennis shack door every morning and tell him to get out of the way so I could go inside.

After he took his sweet time, I would go inside and begin looking for the necessary tools I needed to teach my lessons. One thing you have to realize about tennis pros is that they’re always breaking their strings. Cause they’re playing all day. We all had 3 or 4 rackets but we would eventually break the strings on those rackets too. And since we’re all so lazy, we don’t get them restrung. Instead, we use the demo rackets, which we’re not supposed to use cause those are reserved for clients to help motivate them to buy said overpriced rackets. Since all the pros would snatch these demos – because they’re all breaking their strings too – the demo racket strings would break as well.

When this happened, we’d start using the kid’s demo rackets. These rackets were much smaller and way flimsier and, most importantly, they didn’t look professional. Half of them were girl’s rackets for 10 year olds that had Disney themes on them. Which meant that, it wasn’t uncommon for me to walk on the court with a tiny pink Little Miss Mermaid tennis racket. This when I would occasionally have to play with advanced players. That never went over well.

But the racket wasn’t even the main problem. The main problem was the tennis balls. All us pros were responsible for our own tennis balls. We had to buy them ourselves. And when you have to buy 50 cans of tennis balls at $3.50 a pop, that adds up. Especially when all of the annoying beginner players keep hitting the balls over the fence where they would vaporize to never be seen again. This would annoy me to such a degree that, for a while, I had a rule, that if any of my lessons hit the ball over the fence, they had to stop playing immediately and go retrieve it. They weren’t allowed to come back until they found it.

With the constant dwindling tennis ball supply there was a lot of ball thievery going on. If a pro had gotten so lazy as to not buy new balls in a long time, their ball cart wouldn’t have enough balls for a lesson. So if we were the one with the depleted cart (which I often was) we would steal balls from the other tennis pros’ carts when they weren’t around. Tennis ball stealing became so rampant that each pro started buying multiple locks to lock the top of their tennis ball carts so you couldn’t steal their balls

This never stopped me. I would reach my hand down through the sides of my fellow tennis pros’ carts, scraping the insides of my arms to the point of bleeding as I fished out one agonizing ball at a time until I had enough to teach my lesson. It got so bad that everyone would mark their balls with their initials in permanent marker. This did not deter me if I needed balls bad enough. You can’t show up to a lesson with 15 balls. You’ll be done feeding balls within 2 minutes.

I could go on. But I think you get the point. The first writer writes the generic version of being a tennis pro because they don’t know any of the truths that go into teaching tennis. They’ve never done it before. Whereas I have over a million unique details of what goes on as a teaching pro. And most of them are surprising. I doubt any of you would’ve guessed that that was an average morning for a tennis pro.

By the way, if you want to see a real world example of Writer 1 in action, go watch the pilot episode of “Based on a True Story” on Peacock. The main guy character is a tennis teacher and they write him almost exactly the way Writer 1 wrote it. There’s zero truth to it and you’ll notice how detached you feel from his tennis storyline for that reason.

I suspect this is why I hate shows like Ahsoka right now. I don’t feel any truth at all when I watch that show. Granted, it’s much harder to write what you know if you’re writing fantasy or sci-fi or an action film that takes place in Casablanca. You’ve never been to Casablanca so how are you going to make that sound truthful?

Well, the answer to that is, YOU’RE NOT. You really aren’t. No matter how hard you try. What you should do instead is pick a concept that covers subject matter you know well. The chances of you writing something that will resonate with others will go up exponentially.

But we also have to be realistic. Some writers like writing fantastical stories. And it’s unrealistic to think that you’ll never run into story sequences that don’t have some elements that you’re unfamiliar with. So what do you do if that’s the case?

The answer, believe it or not, is simple. While you won’t be able to write about subject matter that you know, you can always write CHARACTERS THAT YOU KNOW. And if you’re writing characters you know, the character side of your story will be truthful.

This is why it’s a smart idea to base your main character on yourself. Or some aspect of yourself. That way, you’ll be able to write them truthfully. I always tell writers, figure out what your biggest struggle is at this moment in your life. Then have your main character going through the same thing.

If you’re struggling through a hard divorce, your hero should be struggling through a hard divorce. If you’re struggling with belief in yourself, your hero should struggle to believe in himself. If you’re trying to emerge out of the shadow of a successful parent? Yeah, I think you get what you have to do.

Then apply this same approach to as many characters in the story as you can. Base some on other parts of you. Maybe there’s another part of you that’s frustrated that you can’t stand up for what you want. So give that flaw to a supporting character. And for the rest of the characters, base them on people you know or who you’ve met throughout your life. Figure out what represented those people and simply transfer it over to your characters.

If you can do this with your characters, you can write big elaborate screenplays and still have them feel grounded and truthful. Cause all your characters will act with an underlining sense of truth. And you’re writing what you know. If you want to see this in action, check out James Gunn’s studio movies. He’s good at writing gigantic fanciful movies yet still finding the humanity in all the characters. I’m convinced he does that by writing what he knows and always staying truthful.

I can promise you this. If you write a giant action plot for a subject you’ve never had any personal experience with and then you ALSO don’t build your characters around truth, your script is dead in the water. This is something all writers have to figure out if they want to write great stories.

So get to work!

And I’ll be back tomorrow to finally review our second place script for the First Page Showdown!

Reviewing “Seven” in my newsletter brought me back to a time when screenwriters could change their lives overnight. All they had to do was a write a good screenplay and – BOOM – they were millionaires.

Those sales then did double-duty for them, as their names would be splashed all over the trades. This would result in everyone in town wanting to meet with them. Which would establish contacts for these writers that they could use to write high-paying work for the next decade.

What happened to that world and how can we get it back?

A number of things happened. For starters, the internet screwed up the agency’s con. A big part of how scripts got sold in those days was that an agent would send a script out (hard copies, remember, not pdfs) to 7 studios and because all parties were isolated from one another, studios would freak out, afraid to lose a hot spec to a competitor, and therefore bid on that script out of fear, regardless of it it was any good.

Once the internet arrived, Roy Lee, a producer now at Warner Brothers, created an online chat room where assistants could share their thoughts on scripts. Therefore, when a script went out this time, it got photocopied quickly and, within hours, everyone was reading it. These assistants now had a central location to share their thoughts on the script, which would allow a quick consensus on if a script sucked or not.

And here’s the open secret about agency-endorsed screenplays (both then and now) – most of them are bad. Now, that badness was being exposed. So that previous strategy of scaring studios into bidding on bad material didn’t work anymore. This killed a lot of sales that would’ve gone through in the previous era.

Another thing that happened was that the studios all agreed not to share sale numbers anymore. They did this because the news stories about scripts selling for 2 million dollars were driving up script prices. So if you stopped telling people how much a script sold for, the trades were less likely to write a big story about them. And this would allow the studios to bring script prices down to a reasonable level.

I still don’t understand why agents agreed to this. It’s in an agent’s best interest to promote a big spec sale because it will get their client more work as well as themselves more money. The conversation may be more nuanced. I know that, sometimes, a script would sell for a lot less than expected and, in those cases, the agents would want the script price to be vague. That way they could hint that it was bigger than it was.

But just the fact that the trades no longer posted these numbers hurt the script sale business immensely.

But now we get to the biggest reason spec script sales plummeted – THE SCRIPTS WERE BAD. Go ahead and read some of these old million dollars sale scripts. Or just go back through my archives. They’re in there. These scripts were average at best. And so, when they got made, they didn’t make enough money. And when that happened enough times, the studios said, “We’re not following that carrot anymore. We know where that carrot leads.”

The inflection point was 2014’s Transcendence, with Johnny Depp. That was a spec script. That was an expensive movie. And it just SAT THERE. Nothing happened in that screenplay (which I erroneously gave a decent review to). So nobody showed up. And I specifically remember the drop-off of script purchases that occurred after that movie’s first weekend. And the market never recovered.

Which leads us to the post’s big question: How do we bring spec script sales back?

For one, trades have to write about them again. One of the reasons spec scripts became so big in the first place was all the stories that the trades would write about them. If someone sold a big spec, there’d be a giant Variety article that would go into detail about the writer – where he came from, how he conceived of the idea. It was exciting! I still remember reading that article about those valet guys who wrote a spec about valets that made a million bucks. Those stories drive interest in screenwriting. We need them. And nobody writes them anymore.

I’ve thought about writing them myself. But there is some conflict-of-interest. When I have made some calls to get info and developed relationships with those buyers in the past, it would get complicated when I would then have to review the script (or another script from the same production company). I’d notice that I was a little easier on the material than I would normally be. But it’s something I should consider because that sacrifice could be worth the industry having a place where they can consistently read the latest screenwriting success story. Let me know in the comments if you think I should do this. It might mean not being able to review those scripts, though.

We need to publish script sale numbers again. Agents and managers should be promoting those numbers like crazy. It’ll lead to their clients making more money on future projects! Which means more money for them! I don’t care if these spec sale prices are low at first (250 grand, 350 grand). They will grow over time if we keep our foot on the gas and keep writing about these sales.

But the biggest thing you, the writers, need to do is write THE RIGHT SCREENPLAYS and then do a GREAT JOB WRITING THEM. These scripts don’t only have to be as good as the mega-franchise movies. They have to be better. Cause they don’t have any IP behind them. So if you’re a studio taking a chance on one of these scripts, the script has to be really impressive.

Ever since the spec sale business died, the primary measuring stick for a screenplay has been The Black List. And The Black List has become the opposite of the spec sale business. It’s become the Nicholl Fellowship List. It promotes intellectual screenplays over commercial screenplays. It still serves the purpose of getting writers recognized. But it doesn’t help the spec sale trade at all.

To revive the spec sale trade, you have to start with the kind of movie template that actually makes money. Former spec script mainstays like Comedy (The Hangover), Dark Thrillers (Silence of the Lambs), Romantic Thrillers (Fatal Attraction), and Romantic Comedies (Notting Hill), have been relegated to streaming services. Which means you can still make money off of them. But it’s not going to be for a big paycheck.

The movies that spec writers can still write these days and realistically sell for big money include the Action movie (Beekeeper), Action Comedy (Spy), Horror (Us), Buddy Cop movies (Central Intelligence), Guy/Girl with a Gun movies (John Wick), Fun Slasher movies (Scream), Heist (Ocean’s 11), Biopics (Elvis), Based on a true story World War 2 movies (Saving Private Ryan), Contained Thrillers (The Mist), Fun Undercover Cop movies (the original Fast and Furious, Point Blank), Ensemble Big Concept (Knives Out) and to some extent, the general high concept script, as long as it’s upbeat and therefore would sell a lot of tickets (think Jurassic Park or Free Guy).

This is not to rule out updating old templates, like the Submarine movie (Crimson Tide), the Action-Crime movie (Heat), Hitchcockian Suspense movies (Gone Girl), The John Carpenter movie (Escape from New York), The John Hughes movie (elevated teen fare), the big-budget Western (The Magnificent Seven), the pirate movie (Pirates of the Caribbean). Or just that bonkers wowza idea that’s never been done before.

To be honest, you could still write a rom-com that sells for a million bucks *if* you find a clever way to reinvent the genre. Actually, that’s the best way to sell any script for a million dollars. Reinvent the genre. Reinvent any of the movie-types I listed above and you can be a millionaire. I’m not kidding.

Once you’ve got your concept, the hard work begins. This is where the article comes full circle because “Seven,” in many ways, is the perfect spec script. It’s not only a clever idea. But it’s one of the few spec scripts I’ve read where it’s clear that the writer gave 100% on every page. There’s zero laziness in “Seven.”

The core reason that the spec boom died out was that the movies that resulted from those scripts didn’t consistently deliver. And that’s cause the scripts were weak. Most of the value in those scripts was concentrated in the first act. Which meant audiences would go to the theater, enjoy the heck out of the first 30 minutes of the movie, then became increasingly bored with every passing ten minutes. They’d leave the theater with zero energy and wouldn’t recommend the movie to anyone.

So if you want to revive big spec sales, it’s up to you guys. It’s up to you as to how much you want to work on your screenplays. This is why I tell writers, field-test your concept so you know it’s good. Cause if you do that, you know you can spend a year making your script perfect (e-mail me at carsonreeves1@gmail.com – $25 for a logline eval). Cause you already know people are going to want to read it whenever you finish.

Then, get feedback after each draft (figure at least six drafts)! Figure out which characters aren’t working. Make them better. Figure out where readers are losing interest then upgrade the plot in those areas. Even out your tone with each successive rewrite. Stay open to new exciting directions you can take your screenplay, even if it means extending your original deadline. Your goal should be to write something where you can honestly say, “I can’t make this any better.”

The thing you will never be able to control is writing an objectively great screenplay. You just never know how people are going to react to a story. But what you can control is writing the best possible screenplay YOU’RE CAPABLE OF WRITING IN THIS MOMENT IN TIME. I felt that way with “Seven.” I don’t feel that with many other scripts I read.

Let’s change that.

Then let’s sell some damn million dollar scripts.