Search Results for: It

Today (Thursday) is the deadline for First Page Showdown. You submit the first page of your screenplay. I pick the five best first pages and post them tomorrow. The site votes on their favorite. Whoever wins gets a script review next Friday.

What: First Page Showdown

Send in: Title, Genre, Logline, and a PDF of the first page of your script

Deadline: Thursday, September 21st, 10:00pm Pacific Time

Where: e-mail all entries to carsonreeves3@gmail.com

Out of curiosity, I went back and looked at the opening page of the last five scripts I gave good reviews to ([xx] worth the read or higher). Here they are:

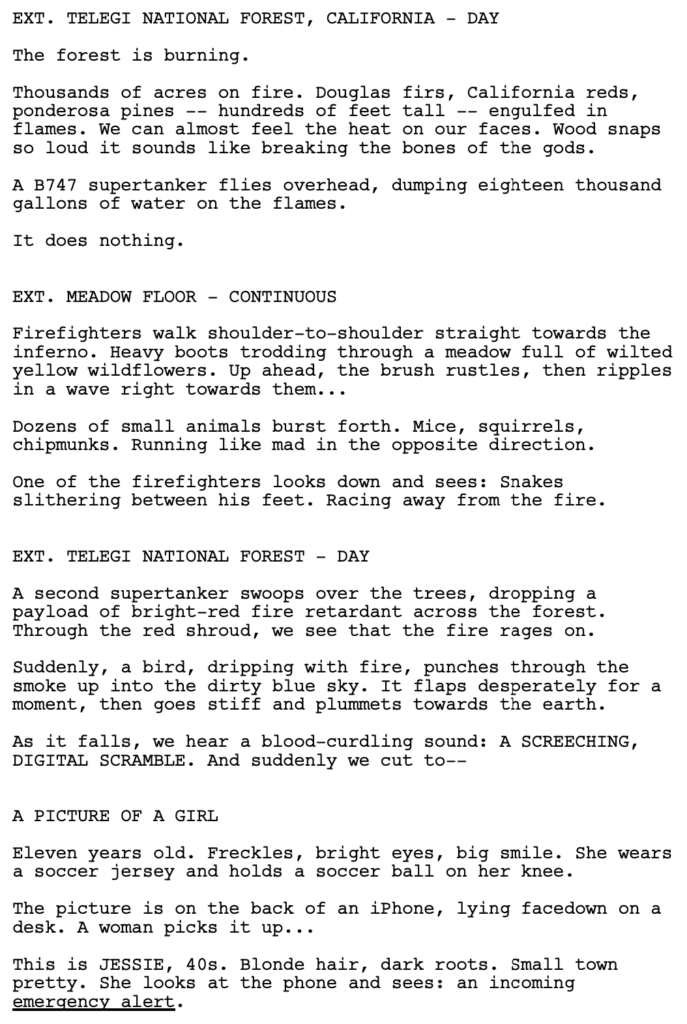

Black Kite – After a devastating wildfire wipes out a small California town, a teenage girl is missing and presumed dead. A year later, an obsessive mother and cynical arson investigator begin to suspect that she’s still alive…and in the clutches of a predator.

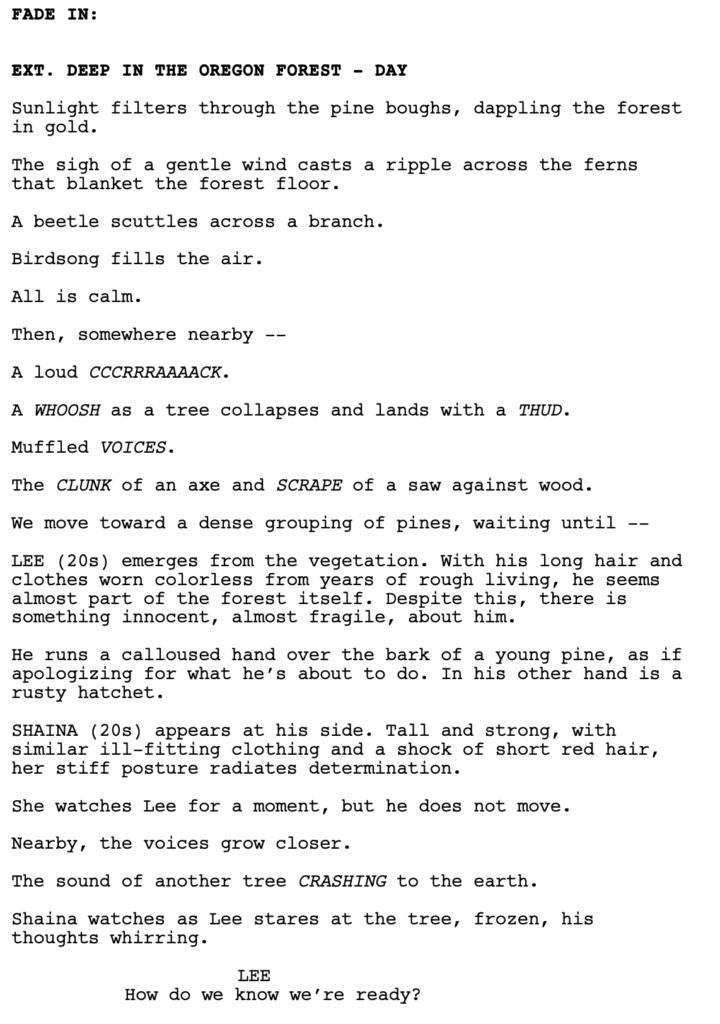

Wayward Son – When her estranged son returns and takes her grandson in the night, a veteran park ranger sets out to rescue him from the clutches of a mysterious cult deep in the Oregon woods.

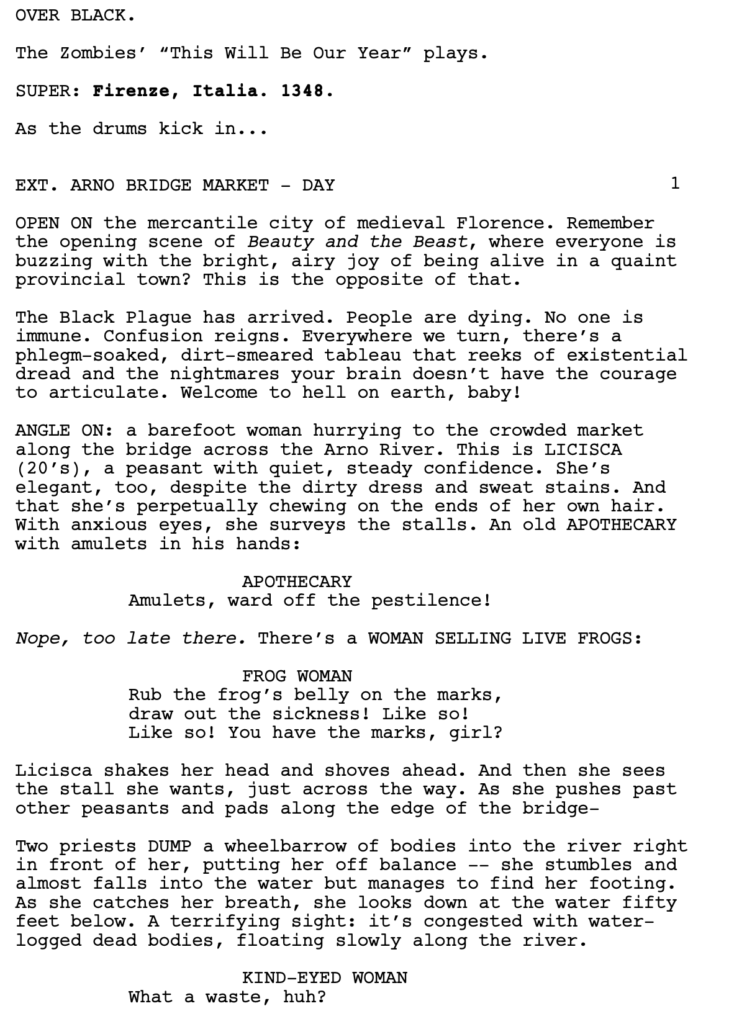

The Decameron – During the Black Plague, a group of rich Italians head off into the countryside to party out the plague in a beautiful villa.

Wild – A werewolf living on a remote farm with her older sister takes in a thief on the run just 72 hours before the next full moon.

The Pack – A documentary crew in contention at the Emmys for their film about wild Alaskan wolves is hiding several big secrets about their troubled 3 month shoot.

You’ll notice that not all of them start with a great first page. I’d say that both Decameron and Black Kite start strong. Wayward Son starts out all right. A little bit of mystery there. Wild throws in the “scar necklace” which makes me want to keep reading so that one was pretty good. And The Pack starts off fairly weak. This would seem to dispel the myth that a strong script is synonymous with a strong first page. Which would seem to indicate that our little showdown this month is irrelevant.

Ahhhh, but it so very much is relevant, my friends.

You see, a script read can be broken down into two categories. Those categories are, “Hafta Read” and “Give It A Shot.” “Hafta Read” is when the reader has to read the whole script whether he wants to or not. Every script I read for the site is a Hafta Read because I need to be able to discuss the story in the review!

However, nobody in the industry has a screenplay review site. For that reason, many of them read scripts from a “Give It a Shot” perspective. They’ll read the whole script if it’s good. But if something rubs them the wrong way early or they just don’t like what they’ve read, they’ll give up on it. And they’ll do it quickly.

Some of you might be confused about when this happens because, say, if a production company wants coverage on a script and gets their secretary to write that coverage then that secretary is in a “Hafta Read” scenario. There are many instances throughout the industry where someone has to read the whole script.

But a lot of scripts make it into peoples’ hands through favors. And unless the reader is close with the writer, those favors almost always exist as “Give it a Shot” reads. This just happened to me recently. I went to visit extended family and one of my family members who knew what I did had a friend who had written a screenplay and asked me if I could check it out for them.

So I did. But I did so under a “Give it a Shot” pretense. If it was good, I’d keep reading. If it wasn’t, I was out. Particularly because I had a ton of work to do at the time. It was clear to me right away that the writing wasn’t up to professional standards. So I didn’t make it past page 5. And I was being generous. I probably went 3 pages longer than I needed to.

Favors are so prevalent when it comes to reading something that most of the scenarios you’re going to be in are of the “Give it a Shot” variety. You’ll cold e-mail a manager who likes your logline and says he’ll check out your script – send it along. I guarantee you, you are not in “Hafta Read” territory with that manager. They’re giving you five pages tops.

That’s the thing with “Give it a Shot.” It means something different to every reader. For some it might mean giving the script 10 pages, others 5, and still others, 1. And the less close the reader is to the writer, the lower that number gets. If I get a script from a friend of a cousin of a friend, I have .0001 level of commitment to that person. So when I open that script, I’m ready to bail if you don’t hook me by THE FIRST PARAGRAPH.

I bring all this up to remind everyone reading this post that it’s highly likely that any industry person you can get your script to is a “Give it a Shot” situation. And because of that, writing a great first page matters. Cause the reality is that these people will be putting outsized importance on your first page and using it to determine whether they like you as a writer and if they want to keep reading.

Even if you have a few people in your rolodex who will give you “Hafta” reads, what happens if they like your script and decide to pass it up to the more important people, the ones with the power to greenlight, the ones with the money? All of a sudden you’re right back in “Give it a Shot” territory, and what are you going to do? Tell your contact to hold off while you write a new first scene? Why not write a good first page already so you can win over both of them?

Okay, Carson. But some of those scripts you gave good reviews to were able to overcome average first pages. So how did they find success? Look, there is a “luck” component to all this. Sometimes you give your script to the right person at the right time and they’re looking for something exactly like that so they’re giving your script a lot more leeway than on a normal read. And if you get somebody with power who likes your script, your script all of a sudden has buzz and becomes a “Hafta Read.”

Even if I wasn’t reviewing scripts for the site, I would still consider the top 5 Black List scripts “Hafta Reads” because they’ve been vetted and that gives me enough confidence to read through any trouble spots the scripts might have.

But most of you aren’t there yet. I wouldn’t even consider low-tier professionals in Hafta Read territory.

You know, the bar for opening pages used to be a lot lower. Even back in the 90s, when the competition was fierce, most readers just wanted to see that the first page was well-written. That the writer could construct proper sentences, the prose was easy to read, and the eyes moved down the page quickly.

But these days, with our mega-ADD addled brains, that’s no longer enough. You need to have that AND you need to have something compelling going on, something that pulls the reader in right away. It’s a lot to ask of one page but if you were hoping for a quiet relaxed career in the writing world, go be a librarian. This is professional screenwriting. It’s where the big boys play. The bar is high.

It’s going to be interesting to see what pages make the cut for tomorrow’s Showdown. Maybe I surprise myself and include a page where nothing is happening but the writing is outright stellar. I just don’t know. But I’ll tell you this. I’m excited to find out. And I’m even more excited to see how good the winning script is.

Today’s article taught me a tremendous lesson about creating memorable main characters.

Genre: Article – Drama/Crime

Premise: Covers the unique job of Gary Johnson, a Houston cop who specializes in going undercover as a hit man to entrap murders-for-hire.

About: This article, which was written all the way back in 2001, was snatched up by indie super-director, Richard Linklater, who cast Glen Powell hot off the success of Top Gun: Maverick. He went and made the movie, which just premiered at Toronto Film Festival, and sold to Netflix for 20 million bucks, the biggest acquisition deal of the year. Linklater read the article all the way back in 2001 but couldn’t find an angle for it. It wasn’t until longtime collaborator Glen Powell came along (the two have worked together on three projects) that a movie emerged, as Powell zoomed in on the final three paragraphs of the article, which focused on a female client who wants to kill her boyfriend.

Writer: Skip Hollandsworth – article; Glen Powell and Richard Linklater – script

Details: about 4000 words

I’ve said it once. I’ll say it again a million times.

One of your primary jobs as a screenwriter is to look for stories that have a familiar element, then spin that element in a slightly different direction.

I’m not using the word “slightly” frivolously. That’s an important part of the equation. If you attempt to spin the familiar element too aggressively, it becomes unfamiliar, and audiences can’t connect with it.

Get Out spun a familiar setup – “Guess Who’s Coming To Dinner” – into a horror movie. Easy to understand. Beau is Afraid is a horror movie told through the lens of extreme anxiety. Nobody understood it.

Then you have the opposite mistake, where there’s no spin at all. That’s when you get movies like Blue Beetle. The exact same superhero origin story we’ve seen a million times already and, by the way, it involves a power suit that, literally, every superhero wears now.

We’ve seen a million versions of hit men. So it was a smart idea to flip that and say, “What if the hit man wasn’t really a hit man? What if he was a cop pretending to be a hit man in order to capture bad people trying to murder others?”

That’s a great starting point for a movie.

The article, appropriately titled, “Hit Man,” isn’t so much a story as it is a summary of the unique life of Gary Johnson. Johnson wanted to work in psychology but when he moved to Houston, he didn’t get his dream job. So he took some psych-adjacent work at a local Houston police office and stumbled backwards into his first murder-for-hire plot. A woman wanted to off her husband because he had taken to complaining too much about her spending. When a friend alerted the police, they threw Johnson into the fake hit man job simply because they had no one else.

Johnson went in with preconceived notions that he was going to have to put on some elaborate fake persona but the reality was the woman just wanted someone to hear what she was going through. Johnson listened, he secured the money for the hit, and the wife was immediately arrested.

Word spread that Johnson had an effective unassuming way about him that got people to open up, a crucial component to convicting these criminals, since you needed them to say, “I want to kill my spouse” for the arrest to hold up in court. So began a strange illustrious career of Johnson going on three hundred murder-for-hire calls in the span of 20 years.

The only call that went sideways was when a woman wanted her abusive boyfriend killed and when Johnson looked into her claim, he learned that the guy was, indeed, abusive. So he decided to help her instead of incriminating her. Which is the kernel of the story that seems to have inspired the movie.

I went into this article expecting to talk about concept. But the biggest thing that came out of it for me was the second paragraph. Here it is…

The man lives alone with his two cats. Every morning, he pads barefoot into the kitchen to feed his cats, then he steps out the back door to feed the goldfish that live in a small pond. He takes a few minutes to tend to his garden, which is filled with caladiums and lilies, gardenias and wisteria, a Japanese plum tree, and rare green roses. Sometimes the man sits silently on a little bench by the goldfish pond, next to a small sculpture of a Balinese dancer. He breathes in and out, calming his mind. Or he goes back inside his house, where he sits in his recliner in the living room and reads. He reads Shakespeare, psychiatrist Carl Jung, and Gandhi. He even keeps a book of Gandhi’s quotations on his coffee table. One of his favorites is “Non-violence is the greatest force at the disposal of mankind. It is mightier than the mightiest weapon of destruction devised by the ingenuity of man.”

The reason this paragraph spoke to me is because, in the last four screenplays I read, I didn’t have any feel at all for the main character. I knew, generally, who they were. But I didn’t *know* know. It’s hard to write a good story if the reader doesn’t have an innate feel for who your hero is.

The primary reason this happens in a screenplay is the writer’s reluctance to add detail. Threre’s a distinct lack of detail in the character’s appearance (an athletic frame tells a completely different story about a person than an obese frame). But, more specifically, there’s a lack of detail in their everyday life. As I read this second paragraph, I was overwhelmed by how quickly I knew this person. The fact that he has two animals he takes care of. The fact that he has this small pond with goldfish that he feeds every morning. That he tends to his garden. The fact that he meditates. Then he reads.

This morning routine tells us SO MUCH ABOUT Johnson. Just the fact that he has a morning routine and doesn’t wing it, tells us that he’s responsible. That he takes care of multiple animals tells us he’s loving. Meditation tells us he values giving time to himself. Reading Carl Jung and Gandhi tells us that he’s an intelligent man.

I probably know this character better in 10 lines than I do any character I’ve seen in the last 20 movies, despite spending two hours with each of them.

The next thing that caught my eye was this paragraph describing Johnson:

In law enforcement circles, he is considered to be one of the greatest actors of his generation, so talented that he can perform on any stage and with any kind of script. If he is meeting a client who lives in one of Houston’s more exclusive neighborhoods, he can put on the polished demeanor of a sleek, skilled assassin who will not sniff at a job for less than six figures. If he is meeting a client who lives in a working-class neighborhood, he can come across like a wily country boy, willing to whack anyone at any time for whatever money he can get.

In other words… ACTOR BAIT! This is one of things you should be looking for when reading an article or a short story that you’re considering turning into a screenplay. You’re looking for the kind of roles that actors would die to play. You should naturally extrapolate that out to the screenplays you write as well. Roles like this allow your main character to become different people which is the ultimate actor catnip.

I find it interesting that Linklater was unable to see the movie angle here. Because it’s pretty obvious. Here’s the last part of the article…

But not long ago Johnson did something out of character for him. He got a call about a young woman who had been spending mornings at a Starbucks in Houston’s Montrose area, talking to an employee there about the cruel way her boyfriend had been treating her. There was no way to escape him, she said. Her only hope was to find someone to kill him. She asked the Starbucks employee if he knew someone who could help. The employee called the police, who put him in touch with Johnson.

But before Johnson contacted her, he did some research into her case. He learned that she really was the victim of abuse, regularly battered by her boyfriend, too terrified to leave him because of her fear of what he might do if he found her.

This is what I call the “but then” hook. You don’t have a movie unless you have a “but then.” Of course it’s going to be fun to watch this police detective inhabit various costumes as he impersonates a hit man. Sooner or later, though, something needs to occur that gives us a plot for our movie! That’s the “but then.” “But then” this woman comes along who it turns out ACTUALLY NEEDS A HIT MAN. Cause her boyfriend is dangerous.

Now you can start to play with narratives, such as, does Johnson become romantically entangled with this girl when he starts to protect her? And who is this boyfriend? Is he a nuisance? Or is he connected to a more dangerous, potentially criminal, network? In which case, is Johnson now in over his head? Now you’ve got a movie.

Finally, when you’re looking for movies that don’t exist in the bigger flashier genres that keep Hollywood afloat (Sci-Fi, Fantasy, Action, Horror, Adventure), there must be the threat of death. You need those LITERAL life-or-death stakes. Cause you’re not giving us any flashy special effects to look at. You’re not scaring us to death. You’re not wowing us with your bottomless imagination. So you need to have the highest stakes possible. People hiring people for murder is a life-or-death situation.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[xx] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Give your main character a morning routine and make it as specific as possible. This morning routine doesn’t have to be in your script. But you at least need to write it out for yourself. Because one of the most telling parts of who someone is, is what they do when they wake up. Do they go on a five mile run? Do they go order 5 sausage and egg McGriddles from McDonald’s? Do they tend their garden? Do they go straight to social media? Do they have an elaborate half-an-hour skin care routine? Note how each of the things I just listed paints a different kind of character. You can create that same effect when describing your own character’s morning routine.

Is “Suits” a perfectly constructed pilot?

Recently, I read an article that the two biggest streaming shows in America were Gray’s Anatomy and NCIS.

I’ve never personally met anyone who’s seen an episode of NCIS so, naturally, this was confusing to me.

I was also confused when, amidst a bottomless pit of shows on Netflix, many of which have had giant advertising campaigns, that the show that had become the most popular was one that had ended four years ago, “Suits.”

We have been led to believe that the TV landscape is dominated by prestige television shows such as Breaking Bad, Succession, Game of Thrones, and White Lotus. But the reality is, shows like Gray’s Anatomy, NCIS, and, yes, Suits, are the shows that truly get the ratings. Just not the love.

I decided to find out for myself if Suits was worthy of all the hype or if it was merely a curiosity brought about by the world’s obsession with Megan Markle (who plays a major character on the show). What follows are my thoughts.

Suits is set in New York City and follows a law firm led by Jessica Pearson, who’s trying to figure out if she should hand the firm down to her best lawyer, Harvey Specter. The problem is Harvey (a young George Clooney doppelgänger) is an arrogant blowhard who only cares about himself.

Harvey is on the lookout for a new lawyer, which is where Mike Ross comes in. Mike is a super-genius who’s had his life derailed by a couple of bad decisions and is in such a bad place that he actually agrees to deliver a suitcase full of drugs for money (that he plans to use for his sick grandmother, of course).

Mike goes to a hotel to make the drop but susses out that he’s being set up and makes a run for it… right into Harvey’s lawyer interviews. Mike stumbles his way into Harvey’s office where he accidentally opens the suitcase and all the drugs fall out.

Intrigued, Harvey asks Mike why he has a suitcase full of drugs and Mike tells him the truth. Further discussions lead Harvey to learn that Mike is beyond a genius and could run circles around all the Harvard applicants in the lobby. The kid is so raw, Harvey almost turns him away. But, in the end, he decides to take a chance on him. This leads to Mike’s first big case, a sexual harassment lawsuit.

Let’s cut to the chase.

Good writing is good writing is good writing.

It’s what I always tell people. Good writing prevails above all. It is almost impossible to find something that’s well written and completely ignored. Because good writing is rare. So when it arrives, it tends to birth a good product.

When it comes to TV, there are three writing ingredients that must thrive. The characters, the dialogue, and conflict. If you are good at these three things, you will be good at writing for television.

Cause TV isn’t so much about plot. Especially episodic shows like this one (case of the week). Plot is more for movies. The reason for that is, a movie needs a conclusion. And that’s where plot leads us. It gives us a goal and then, at the end of the story, we either succeed or fail at achieving that goal.

TV doesn’t need to end. It keeps going. So while there is plot in each individual episode (try to win the case), the plots are devoid of the kind of stakes that really matter. Cause who cares if Harvey and Mike win this week’s sexual harassment case? There’s going to be another one, just like it, next week.

For that reason, audiences come to TV shows more to hang out with the characters. Which is why all your TV writing should start with creating great characters.

Mike is a perfect character. Why? Two reasons. He’s an underdog and he’s super smart. These are two things that audiences DIE FOR. They love underdogs more than anything. This guy who didn’t even graduate law school being thrown into one of the biggest firms in New York — we love watching sh*t like that.

On top of that, audiences love characters who are smarter than everyone. There’s an early scene where Mike sniffs out that two men in the hallway (pretending to look like a bellhop and a guest) may be cops and he’s been set up with this drug delivery. So he asks the bellhop, “Hey, I was thinking about taking a dip later. How’s the pool here?” “It’s one of the best in the city, sir. You’ll love it.” Then we do a quick flashback of Mike earlier walking past the pool and a sign that says, “Pool closed for the summer.”

So we immediately know that Mike is smart. He uses his power of observation to stay ahead of everyone.

Then you have Harvey. I still don’t know exactly what the line is between hateable a$$hole and lovable a$$hole, but I know that audiences love lovable a$$holes. As long as the a$$hole is on our side.

One trick I’ve learned is to put our lovable a$$hole in the room with people who are worse than him. There’s an early scene where a client tries to railroad Harvey for not getting him everything he wants in their deal. But Harvey stays calm and outsmarts the guy, winning the conversation. In other words, if your hero is a bully and you want to make him likable, just add a bigger bully.

When it comes to dialogue, one thing I’ve noticed that these episodic TV shows live by is metaphors. They’re always using metaphors in the dialogue, which helps make the dialogue clever.

So, in the above scene where the client yells at Harvey, Harvey takes out a receipt of funds transferred and tells the guy that any threat to terminate their contract doesn’t matter because the firm has already received his money. The guy huffs out and it’s revealed that the piece of paper was a pointless memo. Harvey was lying.

Harvey’s boss then asks him, “How did you know he wouldn’t look closer and realize you were lying?”

Think for a second how you would write Harvey’s response. Because most beginner writers would write something like, “He’s a bully. And bullies never look closely at the details.”

It’s a lame lifeless line.

Here’s the line that Harvey actually uses in the pilot: “Cause a charging bull always looks at the cape, never the man with the sword.”

Now, is this the most brilliant line in the world? No. But it’s better than, “He’s a bully. And bullies never look closely at the details.” The metaphor automatically upgrades the line into something with more pop.

With TV, you really have to be on your dialogue game. If you are not a dialogue person, definitely stay away from this medium. It’s easier to get away with a lack of dialogue prowess in features because features are more plot driven, depend on exposition more (which is more technical), and are more about showing as opposed to telling. So you don’t have to write as much dialogue if you don’t want to.

Finally, we have conflict. Conflict is very simple to create. You put two people in a room who don’t see eye-to-eye, either about what’s happening in the moment, or in how they view the world in general. Or you give characters little goals and then throw obstacles in front of those goals.

The reason obstacles are great is not just to create conflict – which they do – but because they give your characters opportunities to shine, which is both entertaining and make us like the character more.

So that moment where Mike walks up in the hotel hallway and sees the bellhop and the fake guest — that’s an obstacle. Notice how Mike using the “is the pool open” bait shows him dealing with the obstacle in a clever way, which makes us like him more. The cops-in-disguise then chase him, which is where the conflict comes from.

Also, in the very next scene, when Mike interviews with Harvey, there’s conflict in that scene as well. Harvey clearly likes Mike. But he can’t hire someone who hasn’t even graduated law school. So there’s this tug-of-war where he challenges Mike with a series of problems that Mike passes one by one. Mike eventually wins him over and the conflict is resolved.

So if you’re good at these three things – character, dialogue, conflict – you can be a TV writer. And Suits is a great show to study for how to do it right.

[ ] What the hell did I just stream?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the stream

[x] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: I don’t know if there’s a better setup than taking someone who’s perceived as “not intelligent” (or who has street smarts, or who does things differently than you’re supposed to) and putting them in a scenario where they’re competing against the “smartest people in that industry.” It’s built perfectly for us to feel a sense of satisfaction every week when our supposedly “dumb” hero outsmarts the “smart” guys once again.

Genre: Action/Revenge/Comedy

Premise: Blasting out of prison after being double-crossed by the Mastermind of a heist, a Demolition Expert uses his genius with explosives to enact revenge on the Caper Crew who set him up while simultaneously picking up the pieces of his personal life.

About: The controversial screenwriting talent, Colin Bannon, he of the many wild high concept ideas, is back with another script. This is one of two scripts Bannon had on last year’s Black List.

Writer: Colin Bannon

Details: 115 pages

Colin Bannon reminds me of Mattson Tomlin and Max Landis, two writers who unapologetically seek out big juicy concepts then proceed to write them as fast as possible.

What Bannon has going for him is that he’s the most talented of the “high concept three.” How do we know this? Cause he’s written the best script of the trio – “Birdies,” a pitch-perfect deconstruction of weirdo influencer families. It’s that script that gives me hope every time I open a Colin Bannon script. But I’ll be honest. I haven’t seen Bannon put in that level of effort since Birdies.

Let’s see if that changes with The Demolition Expert.

Gus Bender is the demolition expert on a team of heisters. We meet him with his buddy, Joey Fix, “the mastermind” of the heist, as they break into the “Mind Lab” skyscraper where the CEO, Lazlo, keeps all his most precious items.

They coordinate with Wolf (hacker) and Smoke (driver), as well as their inside man, Stick (a master pickpocket). Using their time-tested abilities, they make their way into Lazlo’s abandoned office where Gus uses a new bomb of his that doesn’t create an explosion to break into Lazlo’s vault. They quickly take 60 million dollars worth of diamonds and they’re out.

Back at the warehouse rendezvous point, where they bring the stolen items to the investor, Gus goes to grab something in the back room, and when he comes back, everyone is gone. Seconds later, a SWAT team shows up and arrests Gus, who goes to prison for ten years.

During that time, Gus plans his revenge. But you have to understand that a demolition expert’s revenge is a little different than a normal citizen’s revenge. Gus is going to blow up everyone who screwed him over, one by one.

He starts with Lazlo’s personal assistant, Travis, who he blows up in a bank. He then moves to the investor, Bank, and blows up his entire casino. He then sets his sights on Smoke, who’s become her own tech CEO. But it’s clear that Gus isn’t getting any satisfaction from these kills. The only person he truly cares about blowing up is Joey. But first he wants to find out why Joey made him the fall guy.

It turns out that Joey will be selling a violin he stole from Lazlo (they waited 10 years for the heat to die down) at a high-end private auction in a few days. Getting to that auction is the only chance Gus may have to enact his ultimate revenge, a revenge that will make even Oppenheimer jealous.

Welcome to one of the wackier screenplays I’ve read all summer.

This one is ka-raaaaazy with a capital “K.”

Where do I begin?

Let’s start here. When Gus is in prison, he gets beat up every day by his giant cellmate. And, every beating, he gets a tooth knocked out. He collects these teeth in a little tin. We have no idea why.

When he finally gets out, he tricks Travis into thinking they’re going to take down Joey together. But Gus only has revenge on his mind. So, while they’re driving, Gus guns their car into a bank, bangs Travis’s head against the dashboard dozens of times until all his teeth are gone. Then Gus brings out the tin of his teeth from prison and shoves them into Travis’s mouth. He then jumps out of the car, leaves the building, detonates the car bomb… ALL SO THAT THE POLICE WILL IDENTIFY TRAVIS AS GUS BECAUSE HE HAS GUS’S TEETH.

I don’t know if that’s the most genius thing I’ve ever read or the most ridiculous, lol. But it’s a great indication of what kind of script you’re getting into with The Demolition Expert.

There is no shortage of zaniness here.

When Gus finds Wolf, it turns out she’s started a mindfulness app that measures your resting heartbeat to keep you “mindful.” So what does Gus do? He hooks a bomb up to the app (somehow ahead of time), and then corners her, explaining that if her heart rate exceeds 183, the bomb blows up. This makes Wolf nervous, so her heart rate keeps rising, which Gus draws her attention to, which makes her heart rate rise even more. And now it’s a desperate race to calm herself down.

Later still, Gus finds Smoke, the getaway driver, who is in the middle of a NASCAR race. He hacks into her headset and explains that he’s rigged her car to blow up if it goes below 200mph. “It’s like SPEED,” he tells her. “But faster.” He then explains that her only salvation is to leave mid-race and get to Santa Monica, never dropping below 200 mph. An impossible feat that she attempts to achieve anyway.

Again, I don’t know what to make of these choices. I don’t want to be disrespectful but they often feel like something a 16-year-old would come up with. Maybe that’s good. Cause that’s the demo you want coming to the movie. But even when you’re writing for younger people, the craziness has to have some level of sophistication to it.

Look at Pixar movies. They’re written for 10-year-olds. But if 10-year-olds had written those movies, they’d be packed with a bunch of farting and burping and silly ideas that didn’t make sense.

I mean, Michael Bay makes an appearance in this movie. Or there’s a moment where a demolition expert, Mary Beth, approaches Gus and tells him that they did the same thing to her. She then offers him to join her on an island for the rest of his life. A woman he’s known for 30 seconds. That’s not sophisticated writing. That’s first draft writing.

That careless recklessness permeates the script.

And yet, to Bannon’s credit, it never totally derails the experience. There’s just enough of a “good time at the movies” feel to the script that you overlook its weaknesses. This is clearly Bannon’s modern-day take on Speed and it’s probably how a modern-day version of Speed would look like. There wouldn’t just be one scenario (a bus that couldn’t drop below 50 mph). The social media generation needs more stimuli, which is what The Demolition Expert gives you. It entertains you with multiple bomb situations.

Every audience member has their own threshold for suspension of disbelief. Some of us need airtight logic to keep our diselief going. Some of us only need jokes and silliness. The Demolitions Expert is much closer to the latter than the former. But, then again, so was Speed. So mileage will vary here.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Scenes that cut between more than two characters involved in a complex situation that needs a lot of description are going to leave a lot of readers cold. These scenes work great on screen. But on the page, they require a lot of concentration to follow. It’s more about us figuring out what’s going on than it is about us being entertained. So this opening heist scene in The Demolition Expert was work to me. It was not enjoyable. I prefer simplicity. The opening scene in Drive covers similar subject matter but it focuses on one singular character in one singular situation – a getaway driver driving away.

Obviously, in Mission Impossible and Fast and Furious type movies, you will sometimes need to write these scenes. But I encourage writers to both simplify them and zero in on the most entertaining component of the scene and feature that. We’d rather read about Ethan Hunt dangling from wires in a secured CIA computer room where one bad movement gets him and his team caught than cutting between 10 different characters all chiming in, where we only understand half of what all of them are contributing. Reading should NEVER FEEL LIKE WORK. It should ALWAYS FEEL LIKE PLAY. Let that mantra guide you.

Do we have a new Top 25 script on our hands!!?

Genre: Thriller

Premise: After a devastating wildfire wipes out a small California town, a teenage girl is missing and presumed dead. A year later, an obsessive mother and cynical arson investigator begin to suspect that she’s still alive…and in the clutches of a predator.

About: Dan Bulla is one of the newer writers on Saturday Night Live, joining the longstanding sketch show in 2019. He also wrote an episode of the Pete Davidson show, Bupkis. This script finished on last year’s Black List.

Writer: Dan Bulla

Details: 111 pages

Mark Ruffalo for Nick?

Mark Ruffalo for Nick?

It is the most wonderful time of the year.

No, I’m not talking about the return of football. I’m talking about the U.S. Freaking Open! I’m currently bouncing around between watching 128 first round matches, having the time of my life.

It was during this trip to nirvana that I thought to myself, “You know what would be nice? Reading a script about a forest fire!” Hey, I can’t defend how my mind works. It does what it wants to do and I try and keep up.

Little did I know I’d be stumbling into a bona fide banger of a screenplay!

40-something Jessie lives in Avalon, California – one of those small Northern California towns in the middle of endless forests. And on this morning, it’s a bad day in Avalon. A massive forest fire creeps up out of nowhere, causing a mad dash to get out of town.

Jessie and her husband, Ken, are assured by the local police that the high school has been evacuated, meaning that their daughter, Wendy, is okay. Still, they barely escape and get to the rendezvous point, where they learn the devastating news that Wendy secretly ditched school that day.

Cut to Wendy and a couple of her friends goofing off in the forest when the fire approaches. They make a run for it but get split up, and Wendy finds herself on a road that is blocked in both directions. Just before she’s about to die, a red pickup truck arrives and a man named Randy saves her.

Cut to a year later and we meet Nick, a private fire investigator. Nick is in Avalon to meet Jessie, who says she has evidence that the fire was not, indeed, caused by a downed electrical generator, but rather by arson. Nick has a lot invested in Jessie’s claim because he’ll receive a giant windfall of cash if he can get the electric company off the hook.

Unfortunately, Jessie seems flat-out crazy these days. She lives in an RV in this shell of a town, collecting burned-up debris in the hopes of proving there’s more to this fire than meets the eye. Nick knows that her theory is weak from the get-go and considers turning around and leaving immediately. But Jessie’s emotional plea to help her figure out how her daughter died gets Nick to stay.

The next day, Jessie shows Nick a mysterious gray line she found in the burnt-up forest. Now Nick is interested. This line implies that the fire was started by arson. Which means somebody planned this. He further figures out that Wendy may not have died after all. Could these two things – the arson and Wendy’s disappearance – be related? And, if so, who, in town, has her? Nick and Jessie will have to team up to find out!

Let me say that this is the first script I’ve read in months where I thought I was a lot earlier in the script than I was. I thought I was on page 60 and it turned out I was on page 85! Usually, it’s the opposite. I think I’m on page 60 and I’m on page 20.

That’s screenwriting code for: this script was awesome.

I liked the script even before I opened it. It’s a fresh concept. We don’t usually see serial killers and wildfires in the same story space. It’s a unique combination. More importantly, it rewrites the investigation narrative. Usually, when we read about a killer or an abductor, it takes place in a city, which means that every investigatory beat in the story is one we’ve already seen before.

Here, the investigatory beats are all unique because we’re in a bunt out town in the middle of nowhere. We’re not going to apartments in Brooklyn asking cousins when the last time they saw Jenny was. We’re in a forest examining dead animal carcasses. I can’t emphasize enough how important this is. Readers read the same stuff OVER AND OVER again. So if your plot provides a world with a bunch of fresh scenarios for your characters to engage in, you’re up on every other screenwriter in the business.

As always, these scripts depend on authenticity. I always say to writers – if you’re writing about a specialized subject matter, you better know a lot more about that subject matter than I do. If I think we know that subject matter evenly, I’m done with your script. Cause I know you didn’t do any research, which means you’re not trying. I don’t have time for writers who don’t try.

I LOOOVED the opening forest fire scene here. It was SOOOOO intense. And the level of specificity to it was impressive (the way this fire spreads sounds eerily similar to what happened in Hawaii recently – and this script was written a year before that happened). There’s this moment where they’re desperately trying to get out of this logjam of cars and they finally break through and they’re racing against the smoke and they look over and there are these deers who are right next to them, also trying to escape. It felt so specific, like the writer was fully tuned into the sequence.

The writer also knows how to navigate the nuts and bolts aspects of storytelling. For example, there’s this early scene with Nick where the writer wants to establish that Nick knows what he’s talking about. You do this in screenwriting because it gets the reader on the character’s side. Readers LOVE when the character knows something that the average person doesn’t.

There’s this moment where Jessie is trying to convince Nick that a bottle rocket was the cause of the fire. Nick takes a look at the bottle rocket and the affected area and says this: “There’s deep char on the right side of the trees. Minimal char on the left. Burns rising, right to left, steeper than the slope. Branches all bent in the same direction. Foliage freeze. That means the wind was blowing right to left at the time of the fire. No odor. No sign of accelerant. It’s burned on top, untouched on the bottom. That tells me that a fully formed, advancing fire swept over this area, right to left, at about six miles an hour. The bottle rocket didn’t start the fire. It’s just some litter you found in the woods.” If there was any doubt that this guy is a fire expert, this assessment puts it to rest.

And then there’s this little moment early on that told me I was dealing with a guy who KNOWS SCREENWRITING. Jessie gets Nick to stay one more day by telling him that, tomorrow, she’ll show him a piece of evidence that will prove the fire was created by arson. The day comes, Nick shows up at her place, and says, “Where’s the evidence?” And she says, “Change of plans. First you’re going to tell me what happened to my daughter.”

The words “change of plans” should be a part of every screenwriter’s vocabulary. Why? Because YOU NEVER WANT THE READER TO GET COMFORTABLE. You don’t want them having a sense of where the story is going all the time. “Change of plans” throws the reader off. Cause now we’re going in a direction that wasn’t a part of the original plan. It’s exciting.

Not that you have to use those exact words (“change of plan”) every time. It’s more about you, the writer, occasionally changing things up so you don’t stay on that same predictable path the whole story.

Oh, one more thing. In a lot of the scripts I read, the bad guys never get the deaths they deserve. They get these quick weak deaths where they don’t suffer at all. This bad guy gets a terrible death and it’s awesome.

All this adds up to a really good screenplay. One of the best – maybe even the best – scripts on last year’s Black List. Definitely check it out!

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[x] impressive (Top 25!)

[ ] genius

What I learned: There comes a time in a lot of scripts where a character will remember something about their loved one and share that experience with another character. These memories are one of the best ways to separate yourself from the average writer. Cause most writers have these boring on-the-nose memories they have their character recall.

“Oh, I remember when Wendy was 7 and she fell in the pool and she didn’t know how to swim and so I jumped in after her and I pulled her out and she wasn’t breathing and I’ll never forget giving her mouth to mouth. I thought for sure she was going to die. But, then, at the last second, she let out a breath. And it was at that moment that I knew my daughter was a fighter.”

Note how unimaginative that is. Note how 99 out of 100 writers would’ve been able to write the same thing. Real memories are unique. They have weird details. They don’t go according to plan. And they rarely line up with the five cliched memories that most writers use in these instances. Note how different, even a little bit odd, the chosen memory Dan Bulla uses for Jessie when she shares a story about Wendy…

“One time, I sat in the living room all night, waiting for her to come home. Just absolutely fuming. She finally snuck in just before sunrise. Didn’t see me sitting there in the dark. She shut the door. Locked it without making a sound. Then she went upstairs, straddling the steps so the stairs wouldn’t creak. And I didn’t say anything. I just watched her. And I remember feeling lucky. Lucky to witness that. Because I was seeing her. The real her.”