Search Results for: the wall

I get questions from writers all the time on things as varied as how to make a serial killer likable to how to end writer’s block. And what I’ve found is that all of these questions are stupid, just like the people who ask them.

I’m kidding! There’s no such thing as a stupid question. Most of the time at least. One of the things I’ve been asked about a lot lately is backstory. Now backstory, as most screenwriters know, is a bad word. We’ve all read or watched that mind-numbing scene where an unprompted character decides that he just has to tell the supporting character how daddy touched him when he was 19.

Backstory is the ugly cousin of exposition, a kid who’s already ugly as it is. And since exposition is often boring, the rule of thumb is to only include it when you absolutely have to. You want to extend that rule over to backstory. It is likewise evil, and therefore to be treated like a pimple on prom night. It MUST be eliminated.

I’ve found, by and large, that the longer screenwriters write, the less backstory they include. There are very successful writers, in fact, who believe that you don’t need any backstory at all. Since a movie takes place in the present, anything in the past is irrelevant.

And someone might argue, “But how can we really get to know a character if we know nothing about their past?” And Backstory Hater would reply, “The only tool you need to reveal character is choice.”

We figure out who people are by the choices they make. This is true in real life just like it is in the movies. If you’re on a first date and an elderly woman falls down in front of you, the choice your date makes is going to tell you a lot about them. If they walk around the woman, we know they’re an asshole. If they jump into action to help her, we know they’re good.

To these veterans, the idea is to create dozens of choices (small and large) throughout the script that your main character will encounter, and to tell us who he/she is through those choices. A small choice might be if your protagonist is given the option to order salad or a one pound greasy cheeseburger. Whichever one he chooses will tell us a lot about him. Ditto if he opens the door for his date or waits for her to open it while he texts away on his phone. Ditto if he chooses to drink 8 martinis or just one.

I tend to agree with Backstory Hater on this approach. I think backstory is troublesome even in the best case scenarios. The revelation of it rarely feels natural and any time we move into the past, we’re halting the present.

So are you telling us never to use backstory, Carson? Like, ever? Can we still visit our childhood friends? Reminisce about our first kiss?

No, you can’t do those things. I forbid it. But you can use backstory in one key instance: When defining what led your main character to inherit their FATAL FLAW.

A reminder on “fatal flaws.” This is the internal “flaw” that holds your character back from being whole. Even if they succeed at obtaining their goal (“Deliver R2-D2 to the Resistance to destroy the Death Star”), they will still have failed if they haven’t overcome the flaw within themselves. Why? Because there’s still imbalance within them. They’re the same person – still unhappy. Luke Skywalker’s flaw was that he didn’t believe in himself. He finally did in the end, which is what allowed him to destroy the Death Star and be happy.

Once you know your character’s flaw, you can target the specific moment from their past (their backstory) that brought it about. So in Good Will Hunting, Will Hunting’s flaw is his inability to let others in. Now that we know that, we can ask ourselves, “What happened when he was younger that stopped him from letting people in?” Well, his father used to beat him regularly. That had some impact. So that’s potentially something we could bring up in the story (which they did).

It doesn’t do the script any good if your hero babbles on about his former life as a male stripper if stripping has nothing to do with what he’s struggling with now. It’s just noise and can actually work against you, as your reader will try to find meaning and importance in a detail that contains neither. Now if your main character’s flaw is that he’s sexually promiscuous and it’s ruining his life, then maybe that stripper backstory becomes relevant.

So to summarize, avoid backstory at all costs. Try to tell us who your character is through their choices instead. But if you must include backstory, only include the details that inform your character’s fatal flaw. Since character transformation is one of the keys to emotionally engaging your reader, information about why your character is suffering from his flaw can strengthen our understanding of that transformation.

And with that, I’ll leave you with a few other tips on how to convey backstory in your script. If you must do it, do it right!

1) Have your character be forced into telling their backstory – If your character is forced into talking about their past, we’re more focused on them being forced than we are on the artificiality of a character discussing their backstory. If your character is being tortured, for example, and asked about his past, we’re not thinking, “Oh, backstory moment!” We’re hoping the poor guy lives.

2) Always keep backstory as short as possible – Just like exposition. Try to disseminate backstory in bite-sized nuggets. Instead of Indiana Jones going on a one-page monologue about the time he was almost killed by a snake, we see him react to a snake in the plane and scream, “I hate snakes.” That’s it!

3) Backstory-as-mystery is often more powerful than literal-backstory – You don’t have to tell us everything. You can hint at things. And this is actually more powerful because it forces the audience to fill in the gaps themselves. Remember in Alien when we saw that giant stone structure of an alien manning some kind of gun/telescope? Our minds were racing trying to figure that out. How boring would that have been if one of the characters knew what it was and explained it in detail to us?

4) Show your backstory. Don’t tell your backstory – The old show-don’t-tell movie rule is multiplied ten-fold when it comes to backstory. It’s always more powerful if you show us. In Bridesmaids, our two main characters walk past our heroine’s failed cupcake shop. There was tons of backstory in that one image.

5) Have others bring up backstory, not your hero – The less your hero is talking about their own backstory, the better. Always think of a way where someone else brings it up. This is why the “resume” scene works so well in movies. It’s an easy way for the interviewer to read off your hero’s backstory without the viewer getting suspicious.

6) Some genres are more accepting of backstory than others – Backstory doesn’t work well inside the faster-moving genres like Thriller and Action. But in a slower drama, it’s expected that some backstory will be offered.

7) A good place to include backstory is the first scene – The biggest problem with backstory is that it INTERRUPTS the present story. Therefore, if you give us a flashback before your present-day story’s begun, you’re not interrupting anything. This is why you see so many movies start with flashbacks and then cut to: “15 years later.” If you’re going to do this however, cover ALL of your backstory in that single scene. Don’t keep giving it to us 70 minutes later.

8) If you can find a way to make backstory entertaining, you now have super powers and all bets are off – This is what the pros do. They’ve figured out all the tricks to hide backstory inside of entertainment. And if you can do that, none of these rules matter because you’ve learned to make backstory just as entertaining as present story. Look at the scene where Clarice goes down to talk to Hannibal Lecter for the first time in “Silence of the Lambs.” Remember the moment when they show Clarice a picture of one of Hannibal’s victims? That’s a writer giving us Hannibal Lecter’s backstory. But we’re so focused on the anticipation of seeing this monster that we never consider for a moment that the writer is doing this. Master this technique and you will be unstoppable!

Genre: Biopic

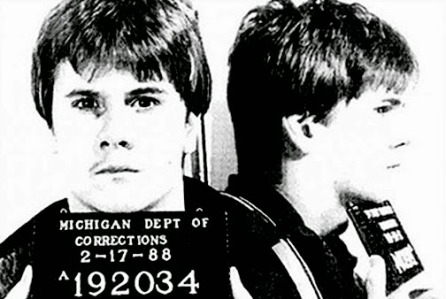

Premise: At age14, Richard Wersche Jr. became an informant for the FBI. He spent the next two years helping take down the biggest drug gang in Detroit, Michigan.

About: There are THREE “White Boy Rick” projects in development, although this one, by most accounts, is the best of the bunch (so far). What’s interesting here (and a reminder for writers who like biopics but are afraid of copyright issues) is that writer-bros Logan and Noah Miller sold this as a spec. They didn’t have any rights to Wersche’s story. To be clear on that, nobody requires you to get the rights to a life in order to write a script about them. You can write the best biopic you can, and leave the “rights” issues to the production company and/or studio that buys the script. Logan and Noah Miller are probably best known for their 2013 indie film, Sweetwater, a Western that starred Ed Harris and January Jones.

Writers: Logan & Noah Miller

Details: 136 pages (undated – but the script went out in February of this year)

When not one, not two, but three production companies are all racing to make a movie about the same person, you figure that person’s life has to be pretty extraordinary. For that reason, I went into this screenplay with some high expectations. And you know what they say about high expectations?

It’s 1986 and 14 year-old Richard Wersche Jr. has the geographic lack of fortune to be born in one of the worst cities in America – Detroit. Detroit used to be the chest-puffed-out capital of the automobile industry. That is until the Japanese started making cars that were cheaper and better.

When that industry broke down, Detroit became a haven for gangs and drugs. But where there is chaos, there is opportunity. And Richard Wersche’s father got the idea to start selling guns to gangs. It’s not exactly legal, but it keeps food on the table. And who’s dad’s best employee? Wouldn’t you know it. It’s his son, little White Boy Rick.

One day Dad gets a knock on the door from the FBI. They know that if there’s anybody who’s got a beat on these gangs, it’s the man selling them guns. So they offer money to dad if he can give them the inside scoop. However, to their surprise, it isn’t Dad who knows everything about every customer, it’s his son, 14 year-old Rick.

As soon as the Feds realize that Rick’s a mini-Einstein, they employ him to infiltrate the drug community. This leads to Rick meeting the Curry Brothers, the number one dealers in the city, and three of the most dangerous motherfuckers you’ll ever cross paths with. The Curry Brothers like Rick. He’s an anomaly. A little white teenage brat who thinks he knows it all. That’s enough to embrace him and make him a key piece of the enterprise.

The movie then follows this little 14, then 15, then 16 year old kid as he’s pulled back and forth between the government and this gang, both of them taking advantage of and exploiting Rick. But Rick figures out a way to rise above it all. And when the Curry Brothers finally get caught with their hands in the crack jar, Rick’s there to take their place, becoming the biggest dealer in the city.

But then there’s no one left for the Feds to take down except for, ironically, the boy who got them there. So Rick is thrown into prison for the rest of his life, and not a single one of those Feds who used a minor to do their jobs ever got punished for it. Rick is still behind bars today, waiting for justice to be served to the men who took advantage of him.

I don’t know if White Boy Rick is a great script so much as it is a great real-life story. And this is what I keep telling you guys is the dirty little secret of screenwriting. If you find that awesome idea or that awesome character, the script will write itself.

I mean we have a 15 year-old taking down some of the biggest drug dealers in the country. He becomes a millionaire, making more money a month than, as he points out, the president of the United States. He ends up running the biggest cocaine trading pipeline between Miami and the Midwest. He’s used by both sides of the system. He USES both sides of the system. It’s no secret why three separate companies are rushing to turn this man’s story into a movie.

White Boy Rick also taught me that utilizing an “impending sense of doom” shouldn’t be limited to horror films. Here, the impending sense of doom is the main story element driving us to keep reading. We know that Rick can’t walk this line forever. Either the bad guys are going to figure out he’s playing them or the good guys are going to stop needing him, and when either of those things happen, he’s toast.

To that end, this script did a great job. I wanted to see how Rick would fall.

If the script has faults, though, it’s its unabashed desperation to land Scorsese as a director. Because Scorsese has made this film so many times now, what was once a unique product has become pure formula. Not unlike the “boy meets girl, boy loses girl, boy gets girl back” formula that drives a rom-com, the Scorsese Tragedy has its own familiar beats. And while Rick was an amazing character, you couldn’t help thinking of Goodfellas, or The Wolf of Wall Street, or Casino, when you read White Boy Rick. It almost feels like one of those scripts was chosen and these new words were simply pasted on top of the old ones, starting with the obligatory first act of pure main character voice over.

It’s a writing crutch we all fall back on. When we write a movie, the first thing we do is go back and watch all the similar movies to see what they did right. The problem with this approach is that, whether you’re aware of it or not, those story beats are seeping into your soul, and without you even realizing it, you’re soon copying those beats into your script. So sure, you may be doing what made that other movie work, but you’re doing so at the expense of originality. You need to deviate from the script sometimes, pun-intended.

Despite the familiarity of the formula, I’d still recommend this script because the title character is so freaking fascinating. You can’t believe this really happened. And the Millers did an excellent job of making Rick likable. This guy did some horrible things. He ran a drug organization that indirectly killed hundreds (maybe thousands) of people. Yet the Millers cleverly present Rick as the victim, the teenage boy who was taken advantage of by everyone in his life, even his own father.

And maybe that’s the lesson to take away from this. When you have an idea this good or a character this good, you can make a lot of mistakes in your script and the script still works. If you have a flimsy or light premise like, to use a random example, Enough Said (that rom-com with James Gandolfini and Julia Luis-Dreyfus), the tiniest mistake (a boring twist) could derail the entire story. White Boy Rick proves what happens when you have the ultimate subject. Much like Rick in real life, the script becomes bulletproof.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: A common mistake I see in monologue-writing is the writer getting too wrapped up in what the character is trying to say, and then delivering an overly-rewritten on-the-nose monologue that’s boring as hell. Monologues are always more memorable when they’re unique, or, like a good story, deviate from the expected path. To that end, I loved this monologue in White Boy Rick. In it, one of the FBI agents asks Rick if he knows who Nancy Reagan is. Keep in mind that the point of the monologue is to convey how important it is (to both Rick and us) that the government win the war on drugs. Most writers would’ve written a very straight-forward dull message about how the war on drugs is destroying America and if they don’t do something soon, the fabric of the country will be permanently destroyed. Here’s how the Millers write it instead. AGENT TURNER: “Well, it turns out that the First Lady is very fucking angry these days. She’s so fucking angry that she’s declared war. A War on Drugs. You know what that really means? That means that if she doesn’t get what she wants, if she doesn’t win this fucking goddamn war, the President doesn’t get any pussy. She locks his dick out of her vagina. And that’s bad for the country. Hell, it’s bad for the whole fucking world. Because when the President of the United States of America ain’t getting laid, he gets really fucking frustrated, and the next thing you know the nukes start flying and we’re buried in World War III with the fucking Russians.”

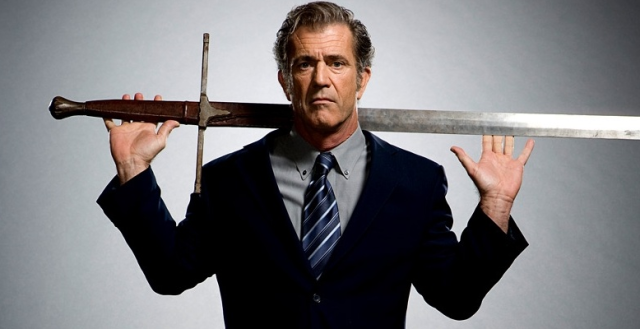

In a fascinating display of courage, Mel Gibson brings us a hero who is the exact opposite of American Sniper’s Chris Kyle.

Genre: Biopic

Premise: The story of the first conscientious objector (a World War 2 soldier who refused to pick up a gun) to win the Medal of Honor, America’s highest award for courage under fire.

About: It’s like Braveheart week here at Scriptshadow! Mel Gibson the director is finally back and that’s a great thing. Gibson is one of the best living directors out there. He just doesn’t make a lot of movies. But Hacksaw Ridge will be his next. What’s extra cool about this draft of Hacksaw is that Braveheart writer Randall Wallace revised it! The original writer is 62 year old Robert Schenkkan, who’s probably best known for writing the 2002 film, The Quiet American with Michael Caine, although he definitely has some WW2 experience, writing for “The Pacific” mini-series a few years back. Vince Vaughn, Andrew Garfield, and Sam Worthington will star.

Writers: Robert Schenkkan (revisions by Randall Wallace)

Details: Marc 12, 2013 draft

You know, it took me awhile to figure out why American Sniper became such a huge hit. But I finally got it. The majority of modern-day war films are liberally slanted. The overwhelming message is that war is bad and it destroys the soldiers who engage in it.

That’s precisely why those movies never made money. Conservatives didn’t want to see them because they depicted war badly. And liberals didn’t want to see them because liberals aren’t interested in war.

American Sniper may not have been a “rah-rah” war film. But it definitely celebrated its subject, Chris Kyle, for killing a hell of a lot of people. Finally, conservatives had a reason to go to the theater. They were no longer being preached to that “war was bad.” And you’re never going to get more liberals to a theater than when a war film is being celebrated by conservatives.

So it seems odd amongst Eastwood and writer Jason Hall’s formula for success that Mel Gibson would bring to market the anti-Chris Kyle. We’re going right back to the liberal slant here. Desmond Doss is a man who joins the army at the beginning of World War 2 and refuses to pick up a gun.

These people are known as “conscientious objectors” and they’re actually supported by the United States government. There’d be a bit of hypocrisy if our country fought for the freedom to have our own beliefs and yet forced counter beliefs on the soldiers we sent out to obtain that freedom. The thing is, nobody actually REFUSED to touch a gun as a soldier. Nobody, that is, except for Desmond Doss.

Hacksaw Ridge spends its first act setting up Desmond’s home life back in the Virginia Mountains, with his depressed father, followed by him falling in love. The first part of the second act has Desmond training to be a soldier. It’s in this section that we see just how anti-gun Desmond is, and how he avoids violence altogether. In fact, when another soldier beats his ass, he just curls up in a ball and takes it.

Desmond’s plan, if you can call it that, is to be a medic. In his view, medics don’t need guns. Because the truth is, Desmond WANTS to be a soldier. He wants to help his country win the war. He just doesn’t want to have to kill anybody to do it.

FINALLY, after we pass the midway point, we get to the meat of the story – Hacksaw Ridge. This is a specific ridge on Okinawa Island that needs to be secured to take the island. The island is a key waypoint in the war. If they take the island, they can use it as a major launching point to attack Japan. In short, take Hacksaw Ridge, win the war (stakes!!!).

This sets up the final act, which is the star of the script by a billion. When Desmond’s company is brutally attacked by the Japanese and the rest of the company runs to safety, Desmond stays back and retrieves every single fallen soldier. All without ever firing a gun! It is for this display that he wins the Medal of Honor.

From a screenwriting perspective, Hacksaw Ridge is a unique challenge. In movies, we like main characters who DO THINGS. Who are ACTIVE. Who are BLAZING THEIR OWN TRAILS. To center a movie around someone whose key action is a negative one (RESISTING) is a tough sell.

And to be honest, that kept me from liking Desmond Doss. Nobody likes the weirdo who refuses to fall in line because of his weird beliefs. I mean seriously, remember the kids whose parents wouldn’t let them dress up for Halloween because of some weird belief?? We weren’t hanging out at those kids houses after school. And it’s also hard to root for someone who doesn’t stick up for himself. When someone tries to fight Desmond, he curls up into a ball and waits for the beating to end???

I actually found myself siding with Desmond’s superiors most of the time. When they said to him, “Just grab a fucking gun,” I was like, “Just do it!” It’s not like he had to fire it. Just hold it for appearances and don’t ever shoot it. There seemed to be ways around this issue that he wouldn’t entertain simply out of stubbornness.

But I’ll tell you what saved this script. The ending. The ending here is fucking awesome. It IS the movie. And you know afterwards why this is called Hacksaw Ridge, a seemingly insignificant title for 75% of the movie.

The ending is great because Desmond Doss finally becomes a hero. He finally DOES something. He’s finally ACTIVE. He’s not just being an annoying pain in the ass refusing to pick up a gun for trivial reasons. He’s the ONE soldier who stays back when his company is gunned down while all the other soldiers – the same ones who were calling him out for his weirdness – ran back to the safety of their camp. And he saves every single soldier who’s still alive despite an entire Japanese company dug in trying to gun him down. It’s a fucking fantastic scene.

In particular, there’s this moment where Desmond has machine gunners off to his left and a sniper off to his right while trying to get to a soldier who’s right in the crosshairs of that line of fire, and he somehow pulls it off. It’s one of the best scenes I’ve read all year.

And it goes to show, if you’re going to write 90 minutes of average and 20 minutes of great, MAKE SURE THAT GREAT IS AT THE END. Because I left this script ready to see Hacksaw Ridge. And I would not have felt that way if this had been structured like Saving Private Ryan, where the movie’s best scene was placed at the beginning.

Hacksaw Ridge shows the power of a true hero. We’re not so sure about this Desmond guy for ¾ of the screenplay, but the second he becomes the bravest man on the battlefield, we love him.

And I’ll finish with a suggestion for Mel, since I know he cares so much about what I have to say. This whole movie is dedicated to this idea that Desmond refuses to pick up a gun. So there should be one scene in the film where the SPECIFIC ACT OF HIM NOT HAVING A GUN saves him. Where, if he had a gun, he would’ve been killed. I don’t know how you do that. But I firmly believe that whatever your hero’s perceived “weakness” is, at a key point in the story, that weakness should become a strength.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Here’s a thing that you should never do in a script. Never tell us your character is “unique” or “different.” We should be able to draw that conclusion on our own. That means coming up with actions or situations or choices that SHOW us your character is unique or different. Early on in Hacksaw Ridge, after Desmond stares at a painting for an inordinately long time, the writers write something to the effect of, “And that’s when we realize Desmond Doss is very different from other human beings.” No. No. Don’t ever do that. Convey weirdness through action, through choice. Go watch Nightcrawler to see how this is done right. The early scene where Louis Bloom makes an awkward proposal to be employed by a man sells you on his weirdness. Gilroy never had to write, “Man, this Edward Bloom is really weird. We see that weirdness in everything he does.” That’s a big no-no and usually indicates that you subconsciously know your hero isn’t as weird as you want him to be. So you literally have to TELL the audience to get it across.

What I learned 2: When a potentially melodramatic scene approaches, consider going with the OPPOSITE line of dialogue than what your instincts are. For example, there’s a scene where Desmond’s father is telling him that he doesn’t want him to go to war. But Desmond has already committed to it. An amateur writer would’ve had the father say something to the effect of, “I love you more than anything. Don’t do this.” Instead, Schenkkan and Wallace have the father say: “You’re a terrible son. I hope they kill ya,” and walk away.

Is this new show FX’s answer to Game of Thrones???

Genre: TV Pilot – Period

Premise: Set in the 14th century, a former knight of the English army infiltrates his old kingdom with the hopes of destroying it from the inside-out.

About: There aren’t many writers who are doing better than Kurt Sutter. The man moved to LA in 2000 and quickly got a writing job on hit show, The Shield. After that, he created Sons of Anarchy. He married Peggy from Married with Children. His script, “Southpaw” was just turned into a movie starring Jake Gylenhaal, and now he’s debuting his new series, The Bastard Executioner, this fall on FX. In a strange twist no one saw coming, goofball crooner Ed Sheeran will be cast as a character on the show. The Bastard Executioner debuts this fall on FX.

Writer: Kurt Sutter

Details: 64 pages

Uh, you had me at “Edward the Longshanks.” Looks like Sutter is just as big of a fan of Braveheart as I am, with Bastard Executioner taking place right after Longshanks rein. And just like Mel Gibson did before him, Sutter’s plan is to take an uncompromising look at the period.

How uncompromising?

Well, let me just say that there are men, as in servants, literally wiping other men’s asses in The Bastard Executioner.

Believe it or not, what I will hereby refer to as “the ass-wiping scene,” is one of the most important scenes in all of The Bastard Executioner. In it, a Baron is sharing his tax strategy with one of his co-workers while having a bowel-movement. Afterwards, a servant rushes over to wipe his ass.

Why is this scene important? Because it conveys to the audience that this was a different time. And that immediately helps sell the unique reality that is The Bastard Executioner. If everything we saw in this show was something we saw in other shows, or in our own lives, then there’s nothing unique to take us back to 14th century England. This one scene showed us: “This is a different world.”

Mel Gibson did this too in Braveheart. In an early scene when William Wallace was a child, his father dies in battle. Afterwards, we see the family cleaning the dead body for burial on their own. It was a reminder that back then, you didn’t have funeral parlors down the street. You had to do the dirty heartbreaking work all by your lonesome. Again, it SOLD the time.

So what about the rest of “Bastard?” Any good? Will this, indeed, be the next, “Game of Thrones?”

I don’t know about that. But there’s some pretty sweet stuff here. Basically, the show revolves around this ex-English knight named Wilkin Brattle whose fellow knights betrayed him and left him to die.

Unbeknownst to them, Wilkin survived and joined a small group of Scottish farmers, content with living a “normal” life. However, when the Brits raise the taxes on the Scots, Wilkin and a small band of friends start killing the tax collectors and taking the money back to the families.

The evil Baron Erik Ventris, the very man who betrayed Wilkin (and assumes him to now be dead), starts sniffing around for who this group of bandits could be, and eventually traces them back to Wilkin’s village. He and his knights kill every woman and child there, including Wilkin’s pregnant wife (we actually get a scene where the wife’s stomach is cut open and the unborn baby’s hand hangs out, lifelessly – youch!).

An understandably un-thrilled Wilkins then assumes the identity of an executioner who just moved into town, and infiltrates the very kingdom he used to fight for. A man who’s now responsible for dishing out death to those souls the British find guilty, will presumably begin a careful campaign of destroying the kingdom from the inside-out.

Sutter seems to be a better TV writer than he is a feature writer. And, actually, this pilot reminded me just how much easier it is to be original in television writing. You could feel Sutter being confined when writing, “Southpaw,” the restrictions of the boxing genre bearing down on him until he inevitably found himself giving us yet another variation of the Rocky format.

But here, you don’t know what the fuck is going to happen (spoilers follow). Almost everyone who you think is going to be a major character on the show dies. Right there. In the very first episode!

Wilkin’s pregnant wife, for example. Dead. Baron Erik Ventris. Dead. The executioner, Gawain Maddox, who’s probably the most interesting character in the entire pilot – DEAD. And it really made this first chapter of Sutter’s show exciting.

Sutter also uses a couple of timeless writing tricks to keep us invested. First, he sets up a “rebels versus the evil establishment” storyline. The British are stealing money from the Scots under the façade of “taxes.” We can’t help, then, wanting to see the Scots retaliate. A little movie called “Star Wars” used the “rebels” approach effectively as well.

Then they have the English brutally (and I mean BRUTALLY) kill the farmers’ wives and children. This turns our need for retaliation into a need for full-on revenge. I mean, seriously, who’s not going to want to read on after that scene?

But Sutter doesn’t stop there. He knows that that the more you hate the English, the more you’ll root for his characters. So he creates this backstory whereby Wilkins was betrayed by his fellow knights and left for dead.

He also doesn’t just make Wilkins wife a wife who’s killed by the English. He makes her a PREGNANT wife. It’s a seemingly small thing but Sutter is using every little trick in the book to make sure you feel anger towards Baron Ventris and the English.

Speaking of the wife, Sutter makes the wise choice of having us get to know her before she’s killed (which happens around the midpoint). I’ve seen writers write dead wives into the beginning of their stories, or even make them backstories, but those never hit as hard as if we get to know the character first. Heck, I was convinced that the wife was going to be one of the main characters of the show. So when she was killed off, I was devastated. And, of course, I wanted revenge!

The main issue I had with Bastard Executioner was the ending. (Major Spoiler!) While killing off Baron Ventris was a surprise, it immediately removed the giant villain from the story. So there was a certain part of me that thought, “He achieved his goal. Story over.”

I guess I’m not entirely sure, then, why he chooses to sneak into the kingdom and pretend to be an executioner. I suppose it’s to bring down the rest of the English and I’m sure that new villains will be introduced as the show goes on. But as of this moment, I’m not dying to get to the next episode. And that wouldn’t have been the case if Baron Ventris had lived.

However, the “secretly infiltrate the kingdom as an executioner” storyline wouldn’t have worked if Ventris was still alive because, obviously, Ventris would’ve known Wilkins wasn’t an executioner. So part of me wonders if Sutter painted himself into a corner here. Did he so badly want this Bastard Exeuctioner storyline that he literally killed off the best part of his story to get it?

I don’t know and we’ll have to see where the story goes from here. But this definitely didn’t have that same “cliffhanger” quality that the pilot for Game of Thrones had, where we end with a brother and sister fucking and the brother throwing a young boy off a tower. That’s something where you’re desperate to see what happens next. Here, part of me feels like the big problem has already been taken care of.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Sometimes we want things so badly in our screenplays, that we sacrifice other parts of the screenplay to get them. It’s your job as a writer to step back and look at the big picture. Decide whether making other parts of your screenplay worse are worth it just to make this part better. Time will tell whether Sutter killing his main villain off in the pilot was the right way to go, but as of this moment, he may have wanted to find a way to keep him, even if it meant sacrificing how Wilkins infiltrates the kingdom.

Yesterday I pulled a Forest Gump. I went out for a quick jog and then just… kept going. And going and going. Until I ended up at some place called Tito’s Tapas. I met a young lady there named Margo and we spent the next three hours discussing Euler’s Equation. We came to the conclusion that the answer was 12. I then hitched a ride back home in a shared-ride Uber that ran out of gas in West Hollywood. So I bought an Astro Burger, took the bus home, and promptly fell asleep for the next five hours. Which is why I don’t have a fresh review for you today. Instead, I’ll share with you a review from my newsletter (sign up here!). Hope you enjoy!

Genre: Comic-Book/Action

Premise: After an evil gangster tortures and maims an innocent man, that man turns into a fast-talking psychotic superhero who will stop at nothing to get his revenge.

About: Hollywood works in mysterious ways. Rhett Reese and Paul Wernick lit the world on fire with their unexpected hit, Zombieland. All of a sudden, everyone associated with that film was the hottest thing in town. But after an ill-advised trip into the G.I. Joe franchise and a failed attempt at turning Zombieland into a TV show, Reese and Wernick found themselves right back where they started: desperate for Hollywood’s attention. Here’s where things get funny. After Zombieland, Reese and Wernick wrote Deadpool, an off-beat superhero script that quickly became one of the most beloved scripts in Hollywood. But writing something everyone loves and writing something that a studio wants to plunk down 150 million dollars for are two different things, and after doing some test footage, 20th Century Fox deemed the material too off-kilter, effectively killing the project. Then, five years later, that test footage leaked online and quickly became persona geek grata, with thousands of online chants that all said the same thing: “Why the hell aren’t they making this movie???” In the five years since the script was written, super-hero films had become the prom king of genres. And it just so happened, studios were now looking for new angles into the genre (remember what I was talking about yesterday? Angles!). Dare I say they were looking for superhero movies that were a little… off-kilter. So Fox grabbed box office mysterioso Ryan Reynolds to play the lead and Deadpool was off to the races.

Writers: Rhett Reese and Paul Wernick

Details: 112 pages (April 12, 2010 draft)

I’d always been curious about this screenplay because whenever the topic of “best unmade screenplays” came up, Deadpool was mentioned.

Now the history of “best unmade screenplays” is a funny one. Before Scriptshadow, there were about 30 scripts over the last 30 years that you’d always hear were “the best unmade screenplays in Hollywood.” These scripts had taken on an almost mythical status, and I was desperate to get my hands on them.

But what I quickly found was that the scripts weren’t all that good. They had a good scene here and some interesting ideas there, but as entire screenplays, you could clearly see why they were never made.

Like that famous script, The Tourist. That screenplay was an idea-machine but it read like a B-movie version of a bad David Lynch film. It just wasn’t good at all. And I realized that a lot of these scripts were propped up by the mere fact that no one could read them.

It’s like hearing about those playground basketball legends from the 70s. In 1979, Bats Jackson scored 55 points in one game. Ten years later, people recall that it was 75 points. By 2015, he’d scored 130 points and performed a triple back flip slam dunk and rode off on a triceratops.

Point being, it’s a lot harder to write a “best unproduced script in Hollywood” these days. Too many people have access to the scripts and therefore, can sniff out the bullshit.

Deadpool was one of the few scripts that seemed to survive this internet-age scrutiny. So I wanted to see how it fared.

Wade Wilson is an angry dude. And he has a right to be. He has to wear a suit and mask wherever he goes because he’s been burned, maimed, and mutilated to the point where even catching him in your peripheral vision would send you vomiting into the nearest storm drain.

We meet Wade (as his alter-ego, Deadpool) slamming into a car going after some guy named Francis, a local bigshot gangster who’s just been released from prison after ten years. As Deadpool tells us (in his ongoing voice over), he’s been waiting for this day forever. Finally, he gets to do to Francis what Francis did to him.

What did Francis do to him? Well, many years ago Francis chained him into his own little personal torture bay, and constructed a series of machines designed to torture Wade as much as a person can possibly be tortured without dying. Remember the Pit of Despair in The Princess Bride. It’s like that times a billion.

Francis even created the perfect torture device. A water tank that would drown Wade, but then, as soon as Wade was about to pass out, pump oxygen into him to keep him conscious, so he could go right back to drowning again, until the point where Wade was about to go unconscious, where he would pump more oxygen into him again, repeating that process for… OVER A YEAR.

So when we jump back to the present and Wade learns things like he’s been diagnosed with cancer, you understand why he’s not that phased. This man has been through way way worse.

The script essentially uses a parallel timeline structure where we follow Wade in the present as he goes after Francis and then cuts back to the past, where we see Francis enslaving Wade. We also see how Wade met the love of his life (Vanessa the hooker) and eventually transformed into his alter ego, Deadpool. Will Deadpool finally get Francis? The script’s online in plenty of places if you want to find out.

So why is this script so admired? Well, it’s got a lot of geek-friendly things going for it. The story itself is actually very simple. This isn’t Avengers where superheroes are trying to save the world. This is a revenge story. A guy wants to kill the guy who maimed him.

But it’s the way the story is told and the flash in its delivery that makes it stand out. Reese and Wernick knew if they told this simplistic story linearly, it would induce mass sleepage. Much better to introduce a mystery in the present (why does Deadpool want to kill this dude so badly??) and dole out hints to said mystery throughout the flashbacks.

The script is also very self-aware. Wade plays with an action figure of himself from one of the Wolverine movies, is absolutely infatuated with Hugh Jackman, collects Deadpool comic books, and at one point, even watches the first act of his own movie (yes, this movie) in his apartment.

The script is ruthless in its violence (note the drowning torture device I mentioned earlier), has an ongoing commentary track in the form of Wade’s comedic voice over, and does things that you just don’t see in superhero movies. For instance, we get a hardcore fucking scene with a superhero.

And then there are things that are just… weird. And that’s good. Like I always say, you have to take some chances with your screenplay. If you’re playing it straight down the middle, expect to see a lot of bored faces staring back at you.

Here we have Deadpool sawing his arm off in one scene and then that same arm growing back later. What?? Deadpool also casually hangs out with Colossus, an 8-foot tall man made out of pure steel. Which would seem normal in a superhero movie except for the fact that everybody else in this story is a flesh and blood person.

Couple all this with some balls-to-the-wall action starring a superhero who uses katana blades to dismember evil villains, and you get the kind of thing that 16 year-olds like to brag that they snuck into. It basically checks all the boxes on the geek checklist.

And yet…

Something was missing. I think all these devices are fun but if there isn’t an authentic core to the movie, if all it is is a bunch of wackiness, then how do you connect to it? How do you care? That’s what I kept waiting for. To care.

There’s something to be said for being relatable. If an audience relates to a character or his situation or his problems or his flaws, they’re much more likely to care what happens to him. Deadpool’s issues were so unique to his particular predicament (being tortured for no reason) that even though the man was dished out some extreme injustice, I didn’t really care if he succeeded in his revenge or not.

And also, the scope of the story bothered me. I don’t know if I’ve been conditioned in superhero movies to expect a goal with some actual consequences, but the fact that Deadpool ONLY wanted to get this one little tiny bad guy made this all feel so small. I didn’t feel like the story mattered enough.

I can admire this screenplay but it’s so jokey, so meta, so focused on the external rather than the internal, that that’s all I could do, is admire it. I never felt it. And that’s what kept this from being great. Still, this is worth the read just for how nuts it is.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: If you have a really really simple story, like here, a man trying to enact revenge, consider infusing an offbeat structure into your screenplay. Offbeat structures can KILL a complex storyline (you don’t want to make something that’s complex even more complex). But for simple plots, they’re perfect. Here, we jump back and forth between the past and the present, using the flashbacks to inform the audience on how we got to this point of our hero wanting to kill our villain.