So, this Friday was the much buzzed-about Severance finale. Word on the street was that it was better than even the beloved first season finale. Well, I binged the last three episodes and have, unfortunately, decided to terminate my show innie and no longer show up at the Severance offices.

There are a couple of reasons why, both screenwriting related. The first is the lack of variation in the tone of the show. It is sad slow scene after sad slow scene after sad slow scene after sad slow scene. Sure, the finale had a lot of craziness. But the three episodes before that made me want to commit show suicide with how slow and depressing they were.

Severance initially struck the perfect balance between ‘serious’ and ‘fun’ in that first season cause it had Dylan, who always provided levity. And it had this fun mystery component to it – a ragtag group of offbeat anti-heroes try to find a way out of a dungeon. But this new season was too slow and sad for my taste. The field trip episode and the “Harmony goes back to her hometown” episode destroyed the series for me. I only watched the last couple of episodes because I heard people saying the finale was so great.

The other reason the show isn’t for me is because it’s too intelligent. It’s rare that anyone says that these days. The Hollywood system seems to be designed to make sure stupidity reigns. But maybe this is why Apple TV is losing a billion dollars a year. Cause they don’t care about following the rules.

I don’t always understand what’s going on in the series or what’s at stake or what the rules are or what the heroes are trying to accomplish, and it takes away from my enjoyment. (Spoiler) In the last episode, I was struggling to understand which Mark was which and why he wanted one girl over the other and which of those versions wanted which of those girls, since every character had two versions of themselves (I think his wife actually had 26 versions of herself) that were constantly switching back and forth. Trying to figure out what was happening began to feel like work rather than fun.

By the way, I don’t begrudge anyone who loves this show. I admire how unique it is. I admire how many creative risks they take. But it’s too sad and too complex for me. That’s all. So say goodbye to Severed Carson. DING!

Back to Outie Carson!!!

And you know what Outie Carson loves? He looooovvveeeees White Lotus.

This night’s episode may as well have been titled “The Aftermath.” The entire episode focuses on the aftermath of the big party last night. For the three women friends, they’re dealing with Jacyln secretly sleeping with Valentin (despite Jaclyn encouraging Laurie to hook up with him all night). For poor Saxon, he’s got to deal with the drunken memory of hooking up with his brother – yikes. For Belinda, she finally slept with fellow masseuse, Pornchai. And Timothy, the father, was seconds away from committing suicide last night.

From a dramatic standpoint within the context of screenwriting, the aftermath is rarely interesting. Why? Because stories fly the highest when characters are going after things and being active. In the aftermath, characters are merely dealing with the memories of being active. And that can never be as compelling as the actual active stuff. Usually.

I say “usually” because there was a little movie called The Hangover built entirely around the aftermath. And I’m pretty sure that movie did okay. But note how it achieved that feat. It placed a ticking time bomb on the story (missing groom 24 hours before the wedding) that forced the characters to be active once again.

You can feel the problems present in this episode due to its dependence on the aftermath format. There’s a laziness to the scenes – a quiet slow pace (a lot of lying around) that doesn’t inspire a ton of plot movement.

The one plot development the show had was Piper’s visit to the Buddhist temple, where she’s hoping to study next year. But first she has to convince her parents, who will come along for the ride and meet the head monk. So, at least here, we have some activity. We have activity because we have a goal – Piper needs her parents to approve of the temple so they’ll send her here.

But let’s be honest. This is probably the weakest storyline in the series. So we don’t care that much. It’s a good reminder that the mechanics of storytelling can only do so much for you. You still have to create storylines we care about. And those boil down to inspired creative decisions, which Mike White is usually great at. But when you’re coming up with a dozen character storylines, some are, naturally, going to end up at the bottom.

What I did like about this storyline, though, was that the monk turned out to be helpful. We’ve been building up to this moment for six episodes and most writers probably would’ve made Piper’s meeting with the monk a disappointment. Maybe make him an asshole, or not care about her, or worse. Mike White does the unexpected, though, and has the monk be supportive, helpful, and even reenergize the dad.

The more I think about this episode, the stranger I find the decision behind episode five to be. Cause Mike White basically creates a mini-climax to the show. A lot happened last week. Which requires him to waste this entire sixth episode on rebooting everybody. I feel like there was a better way to do that. One way would’ve been to make the big party episode 4 instead. Cause that would’ve been midway through the season and a good “midpoint” plot marker. By making it episode 5, it throws the last three episodes out of balance.

There are two other lightweight attempts at adding some activity to the episode. The first is security guard Gaitok needing to get the gun back from Timothy, who covertly stole it a couple of days ago. And the second is Rick’s (Walton Goggins) Beijing trip where he’s attempting to orchestrate the murder of the man who killed his father.

In regards to Gaitok’s storyline, something about it isn’t revving on all cylinders. Technically, when I break it down, the stakes are high. Gaitok needs to retrieve the gun before his boss finds out because if his boss finds out, he’ll surely be fired. And, if he’s fired, there’s no way love-of-his-life, Mook, will go out with him.

And yet it never feels like he’s truly in danger of anything bad happening to him. There’s something missing from that storyline that makes the stakes feel low. One possibility is the “connect-the-dots” approach. This is when you build stakes around a series of dots that the reader must connect in order to understand the severity of the situation. For example: Joe has to let his daughter go to a concert (dot 1) so that he’s in good standing with her (dot 2), because she’s friends with another girl at school (dot 3) whose father happens to be the CEO of a compay Joe wants to work for (dot 4) that’s having an event he wants to be invited to (dot 5), etc. At a certain point, we lose interest in keeping track of the stakes. It’s always better if the stakes are upfront and clear.

As for Rick’s murder plan, that storyline actually has some potential but holy Moses is it developing slowly. Wow is that storyline moving at a snail’s pace.

All in all, it’s a tough episode for my idol, Mike White. He kind of painted himself in a corner, making his job difficult. But in spite of all this, I still think it was a solid episode. I’m fascinated by Saxson’s character and watching him realize what he did last night and how he’s going to mentally deal with that moving forward in his life.

There were also little moments I enjoyed, such as wife Victoria telling Timothy that if they ever lost all their money, she wouldn’t want to live. This is classic Screenwriting 201 stuff here, with dramatic irony driving the exchange. We know what Victoria doesn’t know yet. Which is that they *have* lost all their money. So seeing Patrick realize the effect this realization is going to have on his wife is fun stuff.

Look, Seasons 1 and 2 of The White Lotus are perfect television. I realized that could not be replicated a third time. But it’s still good. I care about a lot of these people and I’m excited to see how this ends.

Two episodes left!

By the way, everyone, THE SCENE SHOWDOWN IS THIS WEEK! You have until Thursday to get your scenes in. Here are the submission details.

What: Scene Showdown

Rules: Scene must be 5 pages or less

When: Friday, March 28

Deadline: Thursday, March 27, 10pm Pacific Time

Submit: Script title, Genre, 50 words setting up the scene (optional), pdf of the scene

Where: carsonreeves3@gmail.com

We’re getting close.

Next week is Scene Showdown!

What: Scene Showdown

Rules: Scene must be 5 pages or less

When: Friday, March 28

Deadline: Thursday, March 27, 10pm Pacific Time

Submit: Script title, Genre, 50 words setting up the scene (optional), pdf of the scene

Where: carsonreeves3@gmail.com

So I wanted to give you one last article to beef up your scene-writing skills. And the concept we’re going to tackle today is something called “The Scene Soundboard.”

I’m going to be upfront with you—I’m not an expert on soundboards by any stretch. However, I do understand that audio engineers work with these giant mixing boards packed with sliders, knobs, and controls. By adjusting specific faders or tweaking certain dials, they can manipulate the audio output.

The same thing is true with scene writing. You have these knobs. And you can either dial them up or dial them down and, by doing so, you change the intensity of the scene.

In order to understand how to do this, you must first understand how 90% of scenes are constructed. You have a character who wants something in the scene then you have a character who stands in the way of them getting it.

That person may actively not want to give it to them, or they may just obliviously be in the way. For example, on the former, a husband may want to hang out with his buddies tonight. Meanwhile, his wife wants him to come to her boss’s dinner party. The hubby’s goal is to hang out with his friends and his wife is actively trying to prevent that.

As for the latter, imagine a bank robber scoping out a bank for weaknesses (his goal) that he wants to rob later. There may be a bank manager who strolls up and starts annoyingly asking him if he wants to open an account at the bank. The manager doesn’t know this guy is casing the joint, yet he’s still in the way of our bank robber achieving his goal.

By the way, note how each situation changes the dialogue. In the first, the conversation is straightforward. The married couple is *literally* debating whether he should get to hang out with his friends. The conflict in the second conversation, meanwhile, is happening below the surface. Neither character is talking about what the protagonist actually wants to do, which means much of the focus of the scene is being conveyed through subtext.

But anyway, that’s not what today’s article is about.

Today’s article is about understanding how to amp up any scene with basic scene structure (a person who wants something and a person who stands in the way). Getting back to our original analogy, I want you to imagine this giant mixing board. On that board are these KNOBS. You can dial these knobs up a little, a medium amount, or a lot, depending on how much you want to juice up the scene.

These four knobs are…

Stakes

Resistance

Urgency

Emotion

The number one way to amp up a scene is, without question, stakes. The more that’s on the line in the scene, the more compelling the scene is going to be. It’s simple math.

Let’s say we have a character who’s going to steal something. Remember that Netflix movie, Emily the Criminal? Let’s say Emily has to steal a random guy’s wallet for her new boss. We have our goal (steal the wallet) and we have our stakes (she’s doing something illegal, which is dangerous, and the mark could potentially catch her in the act, creating a problematic situation).

But let’s say we get on our Screenplay Soundboard and dial up the stakes knob. Instead of having her try and steal a guy’s wallet, she tries to steal… A CAR. Now we’ve got some REAL consequences. Grand theft auto is no joke. And guess what? That’s the scene they went with in the movie and it ended up being the best scene. Coincidence? I don’t think so. That’s the power of dialing up the stakes knob.

Next, let’s look at resistance. Resistance is simply upping the knob that has the opposing character in the scene getting in the way of our hero achieving his goal. The more you turn this knob up, the more intense the interaction gets, which creates more conflict.

Let me use one of my favorite scenes ever as an example – Jerry Lundegaard meeting with the two criminals he’s hiring to kidnap his wife in the film, Fargo. Just like any scene, there was a way to write this scene with the resistance knob turned down. You could’ve made the kidnappers annoyed, but eager to get their money and, therefore, cooperative.

But that’s not the route the Coen brothers went. Instead, they turned up that resistance knob to 11, making the two kidnappers highly resistant to help Jerry. Carl is determined to get Jerry to admit he fucked up about the meeting time, leaving them sitting there around for an hour, and Psycho Gaear intermittently stares at Jerry like he’s going to kill him. This creates all sorts of conflict and makes Jerry’s goal much more challenging.

Again, a lesser writer would’ve made the two kidnappers annoying, but ultimately agreeable, so he could get what he wanted out of the scene and move on to the next one. The good screenwriter ups that resistance knob and makes it very uncertain whether Jerry is going to achieve his goal or not.

Moving on, let’s check out the urgency knob. The urgency knob is effective but, if we’re being honest, it’s the most simplistic of the four knobs. By upping this knob, you condense the amount of time that the protagonist has to achieve his goal in the scene.

So, let’s say you have a scene where a wife has a last minute change of plans and needs her husband to take their kid to school tomorrow. So they’re getting ready for bed, the wife puts forth the problem and what she needs from the husband, but he’s got his own big day tomorrow so he’s resistant.

Could you get a good scene out of this scenario? Sure, an okay one. You’ve got a character who wants something. You’ve got a character who’s resistant, which is going to create conflict. The stakes are pretty low, though, and there isn’t an obvious way to dial that knob up. So what can you do? Well, that’s when you bring in the urgency knob.

Instead of setting the scene at night, before they go to bed, where the two have all the time in the world, rewrite the variables so the wife finds out about the problem 5 minutes before she leaves for work. In other words, set the scene in the morning, with 5 minutes before everybody has to leave, and now the URGENCY of the situation is going to dial up the intensity of the scene considerably.

Lastly, we have the emotional knob. Now, the emotional knob is the hardest knob to play with. It’s way way up there in the far corner for a reason. Because unless you know what you’re doing, it can hurt you just as much as it can help you.

The way that you use the emotional knob is to move away from the logistics of the scene (goal, resistance, stakes, urgency) and go internal. Ask yourself what’s going on INSIDE the characters that could up the intensity of the scene.

There was this old teen comedy from the late 90s called Can’t Hardly Wait. It followed a bunch of characters throughout the night at a giant house party. One of the main subplots had these two characters, Denise and Kenny, both of whom were looking forward to the party for their own reasons, get stuck in the bathroom together all night.

Now, the directive for this subplot was, obviously, having these two characters fall for each other over the course of the movie. But let’s say you’re writing that story (or just a scene from that story), and the scene is dull. Whenever you go back to them, there’s something lacking. Stakes aren’t really relevant here. Urgency is a non-factor cause you want them here the whole movie. And resistance isn’t really relevant either cause neither character has the active goal (they’re both stuck in the same situation – neither of them wanting to be here).

Well, this is where you want to reach up as far as you can to the right side of the board and play with the emotional knob. Which is exactly what the writers do. They create this backstory with the characters where they used to be really great friends in middle school and then, when they reached high school, the guy moved on and got a whole new group of friends, leaving the girl behind.

Note how turning up this dial ups the conflict considerably. Now there’s this unspoken thing that one of the characters did to the other lingering under everything that they say. Now we’ve got a storyline we can keep coming back to, one that consistently gives us strong scenes.

And there you go. This is how you use your Scene Soundboard to dial up the intensity of scenes. And remember, like I said, you control the degree to which you turn up the knob. You can dial any of these knobs up a little or, depending on how intensely you want the scene to play out, a lot.

Believe it or not, you don’t always want to dial a scene up to 100. If every scene were 100, then no scene would stand out. But what you don’t want to do is write scenes where all the knobs are set to 0. And I see that far too often. As in, when I read an amateur script, 75% of the scenes are set to 0 on all four knobs. That’s unacceptable.

But that’s often because the writer doesn’t know about these knobs or how much power they have to create great scenes with them. Now you know. So, I give you permission to unleash these powers on the scenes you write for the showdown and the scenes you write for all your scripts going forward!

Genre: Sci-Fi

Premise: In the not-too-distant future, where a new technology allows an individual to project their psyche into the body of another, thus creating a body-sharing gig economy, a financially-struggling married couple accepts a wealthy man’s proposal to use the wife’s body for a single night, but soon that decision causes their relationship and lives to spiral out of control with fatal consequences.

About: Today’s writer, Mark Townend, has been at this for at least 13 years! I know this because he signed up for the newsletter in 2012. He has one feature credit, a movie he co-wrote with Anthony Bourdain titled, Bone in the Throat, about a young ambitious chef who becomes mixed up with the East End London mob when he witnesses a murder. This script finished with 15 votes on last year’s Black List.

Writer: Mark Townend

Details: 99 pages

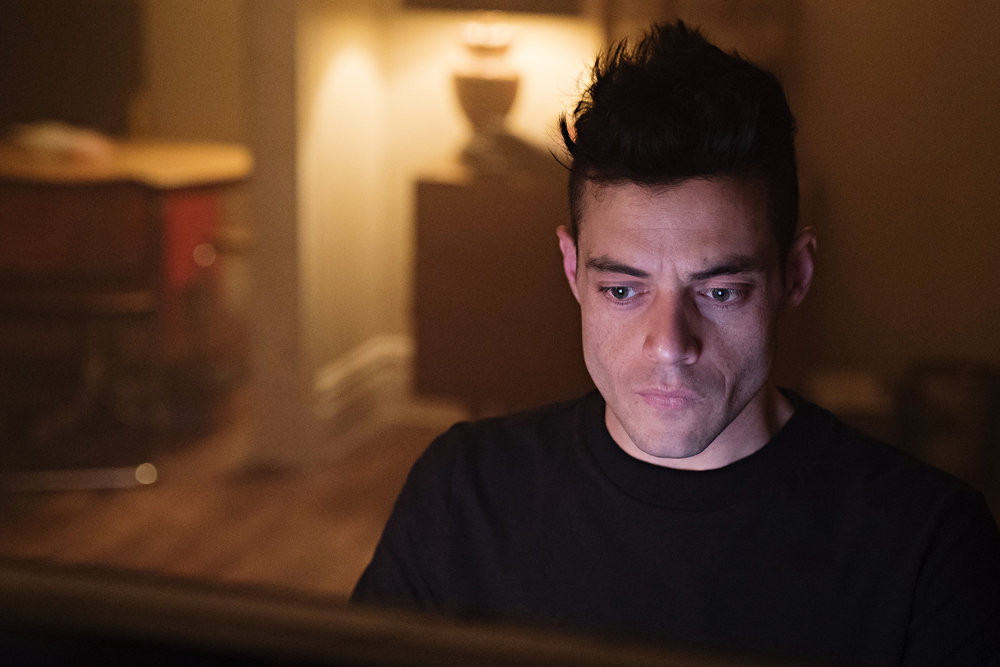

Rami Malek for Mike?

Rami Malek for Mike?

We’re going high concept today!

And I don’t want to waste any time getting into it.

So let’s go!

Mike and Jodie are a young struggling married couple drowning in debt. Jodie doesn’t seem to like Mike that much, bristling at even the smallest, most mundane, statements he makes.

One day Jodie’s ex-boyfriend, Sean, who’s become rich beyond anyone’s wildest dreams, calls Jodie and wants to have dinner. He’s going to bring his girlfriend, Shelby, and encourages Jodie to bring Mike.

After some reminiscing, Sean hits Jodie with a whopper. Despite looking great, he has Stage 4 cancer. He and Shelby have been discussing what he might want to do in his final days and he told her he would love to have one more night with Jodie. Shelby is game for this, with one stipulation.

You see, in this near future that the script takes place in, a new technology has swept the nation – Timeshare – where you can rent people’s bodies. Shelby would “rent” Jodie’s body for the night, allowing Sean to be with “Jodie” one more time, but it wouldn’t be cheating because Shelby would be inside that body. Oh, and Sean would pay them 7 million dollars for this rental.

Jodie feels a little weird about the whole thing but Mike gives her the okay and away we go. The very next day, Jodie spends a night with Sean and comes back home. Immediately, it’s clear that Mike is having second thoughts about the whole thing. He keeps imagining the two having sex. And when he catches Jodie sneaking out to see Sean for dinner, he really freaks out.

So Mike does a Timeshare of his own, jumping into some other man’s body so he can be at the restaurant and listen in on the date. It’s inconclusive what the two discuss but, at this point, Mike is in full-on meltdown mode.

Things descend rapidly from there, with Jodie visiting Sean at his highrise condo. But something happens during their meeting and Jodie *supposedly* shoves Sean out the window, where he plunges 40 stories and dies.

(spoiler) I say *supposedly* because we quickly find out that Mike pulled a timeshare and jumped into Jodie’s body and killed Sean. And now he’s letting Jodie take the fall for the murder! When Jodie realizes this, she puts one last plan together to take Mike down. But she’s going to need Shelby’s help to do it.

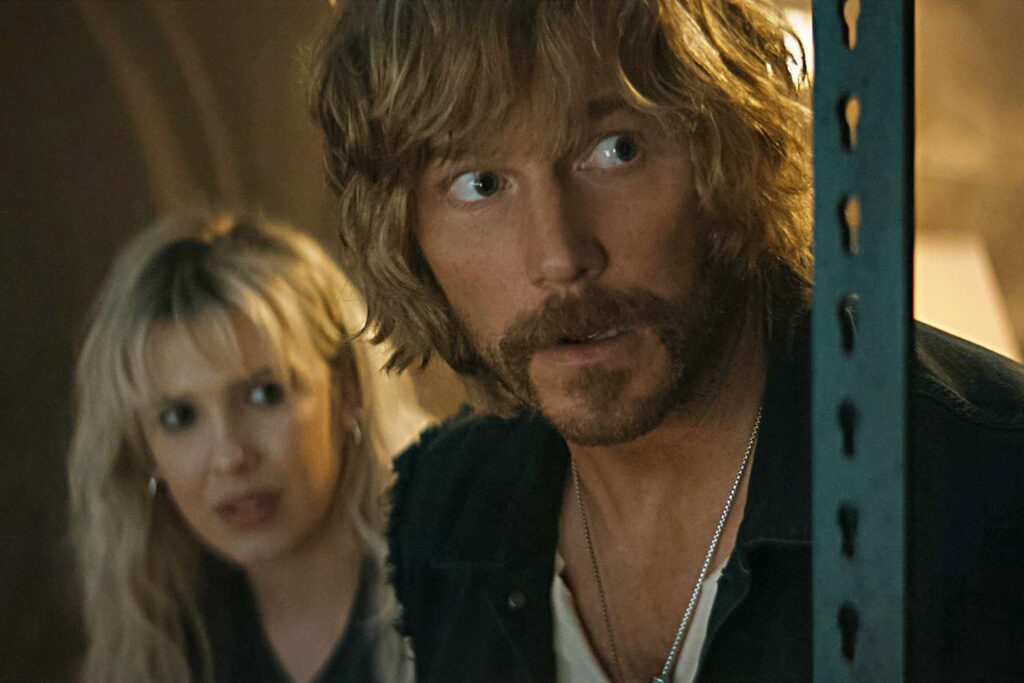

Katherine Waterson for Jodie?

Katherine Waterson for Jodie?

The pillar that sets up your story – the very concept your script is based on – must be the strongest pillar of all. If it is weak, if will be unconvincing, and the entire script will far apart.

I didn’t believe this setup at all.

It doesn’t make sense. You have an old girlfriend. You’re dying. You want to have one last date (as well as sex) with her, so you tell your current girlfriend this and she agrees to it. Right there, I no longer believe in the story. I mean, come on. There’s no way Shelby is agreeing to this. The fact that your boyfriend wants to bang the body of his ex would be a non-starter for 99% of the female population.

But even if you go along with that, Sean’s *request* doesn’t make sense either. It’s not like he’s paying 7 million dollars for the body of some gorgeous influencer – Olivia Dunne – who he’s never met before and just wants to have sex with her.

He’s specifically requesting his ex-girlfriend, a person he was (and may still be) in love with. Which means you don’t just want her body. You want HER. You want to spend time with that person again. So getting a Timeshare where you only get her body and not her mind makes no sense.

And those two things create such a shaky setup that anything you build on top of it crumbles.

The next big problem is Mike. I liked Mike’s character description (which I’ll get into in the ‘what I learned’ section) but Mike is an incredibly unrewarding protagonist to follow. He’s dumb. He’s thin-skinned. He’s selfish. We don’t like anything about this guy yet he’s our avatar throughout the story.

Although Jodie has her issues too, she’s much more sympathetic than Mike. So, what happens is, we see this whole story through Mike’s eyes, then when all the secrets are exposed about who was in whose body, we switch over to Jodie as the protagonist for the final act.

I don’t think you can do that. You ask us to watch the movie through one character the whole time, then you say, “Psyche! It’s actually this other person’s story.”

I just watched a movie, Companion, that dealt with this situation much better. Cause it had a similar problem. Due to people not being who they really were, we had to kind of jump around to different characters taking the lead. However, the writer never forgets that we need to see this story through Iris’s eyes. So even though we occasionally jump over to Josh’s POV, we always come back to Iris.

None of this is to say that the script doesn’t have potential. I actually like this idea. I like any idea where you’re playing with different personalities being in the same body. Because it’s high concept, which means the script gets more traction, actors get to play two or more different parts, which means heavier interest from talent, and it opens the door for all sorts of clever plot developments.

But that’s the trick, isn’t it? It’s got to be clever. If you write these types of scripts with a hammer, they get crushed. You have to use a scalpel and a steady hand the whole way through because the audience is expecting the movie to be smart.

For that reason, these types of scripts are the ones that need to be rewritten the most. Cause all of your first ideas (Mike was in Jodie’s body when she killed Sean!) are going to be ideas that the audience predicts. You need to use every draft to throw those first ideas out and go deeper. Go twistier. Go more unexpected!

Companion is a great example of this. It’s a really clever movie where all the reveals come right when they need to. You know this because we never see them coming. Meanwhile, Timeshare was way too clunky in its execution. There was never a plot beat I didn’t predict. And there was never a plot development where I thought, “That was deftly crafted.”

I mean we’re talking this needs 7 to 8 more drafts to fully unlock its potential. You need to go down some dead ends in a few drafts. Figure out what the story is really about in the next couple of drafts. And then bring it all together in the final three drafts. It may be worth that investment, though. This *does* feel like a movie to me. But it’s just not where it needs to be yet.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: On page 5, we get this description of Mike: “Mike likes the world to see him as a nice, enlightened guy. But he’s also frustrated, insecure, and desperately wants to “matter.” And sometimes those things get the better of him.”

I love this description because it doesn’t bury itself in writerly phrases and metaphors that hide who the character is. It just tells you who Mike is in simple clear terms. So many times, I get writers trying to be writers in their character descriptions and, in the process, describe some totally vague person. For example, someone else might write Mike’s description like this….

“Mike, a speeding train of a man with a ten-ton glob of frantic gray matter pulling at his nervous system 24/7 is always trying to be a man’s man when he’s more like a half-inflated basketball…” Like, what does that even mean?

Look, there are some writers who can put together the perfect metaphor to describe their character. But, if you’re not one of those writers, just TELL US WHO YOUR CHARACTER IS IN SIMPLE TERMS. I promise the script will benefit.

Did I just read… a good comedy script???

Genre: Comedy

Premise: An unemployed doofus who lives with his mother is asked to pose as a couples therapist for a sports agent to covertly manage the agent’s wife, only to stumble into a new career as a shrink.

About: This was a big spec sale that came together earlier this month. Miramax beat out a bunch of other suitors. The production company is Boulderlight, who just produced the awesome, “Companion,” so let’s keep an eye out for them in the future, since someone over there seems to have an eye for good writing. Writer Brandon Cohen has actually been writing in Hollywood for over ten years. Most of his work has been on kid’s shows.

Writer: Brandon Cohen

Details: 110 pages

My choice for RJ is Ben Schwartz

My choice for RJ is Ben Schwartz

I met with a producer recently and we were talking about how bad comedy scripts have gotten. We racked our brains to try and remember even one good one from the last five years.

Well, I got news for you. TODAY I FOUND ONE.

I don’t know how it happened. I don’t know where this writer came from. I’m just happy to have been able to laugh out loud for two hours.

RJ is one of those 30-something lovable losers who’s so self-involved that he doesn’t even realize that his relationship is crumbling around him. His girlfriend forces him to take couples therapy sessions which confirms what she already knows – this guy sucks – so she leaves him.

RJ Doordashes and lives with his mother, giving him few prospects for a next romantic adventure, but gets lucky when an old friend invites him to a UFC event. It’s there where he meets Jordan, a manager for a UFC superstar named Sean (think Connor McGregor). While in his friend’s suite, he meets Izzy, a beautiful perfect girl he instantly falls for. But she leaves before he can shoot his shot.

Later, RJ and Jordan get to talking about his recent therapy sessions and, jokingly, how he believes that his girlfriend was giving the therapist extra money under the table to side with her. This is a lightbulb moment for Jordan, who’s been having problems with his wife. He comes up with this idea where RJ can pretend to be a couples therapist and side with him during their sessions so his wife gets off his back.

RJ is reluctant at first until Jordan offers him 500 bucks a session. Therapist it is! RJ has no idea what he’s doing but, of course, does any therapist know what they’re doing? RJ fakes his way through a bunch of mumbo-jumbo advice, always siding with Jordan, and soon he’s getting referrals from other guys in the UFC agent/manager space.

All of this is going great until Sean comes to him for a session. And who is Sean’s girlfriend? IZZY! RJ must now make Sean believe that he’s supporting him in the sessions while, at the same time, not piss off Izzy, who he’s secretly in love with. There is literally no way this can end well. Which is exactly why we keep reading until the end! :)

I’ve been reading a lot of comedies lately.

And I’ve learned that comedy, in screenplay form, boils down to getting five things right. Those are….

SET PIECES

FUNNY CHARACTERS

CONFLICT

MINING THE UNIQUENESS OF YOUR PREMISE

and

VOICE

If you can nail three of these five things, you’ll write a funny script. Nail four of them, you’ll write a really funny script. Nail all five and you’ll write a hilarious script.

Set pieces are the showcases of your comedy so that’s where you need to focus most of your efforts. Sure, you can spend time trying to come up with funny lines spread throughout your screenplay. But it’s the set pieces that audiences will remember so that’s what you want to spend most of your time on.

And a set piece doesn’t need to be some big elaborate thing. It just needs to be concept-relevant and funny. My favorite set piece in this script was RJ’s first therapy session. He has no idea what he’s doing. He’s making things up as he goes along. We’re waiting for him to screw up and get caught. It’s hilarious.

Next requirement – the characters who have the most screen time in your story need to be as funny. That sounds obvious but a lot of writers screw this up. They create sort of funny characters then try and force funny lines into their mouths. This makes sense when you consider that writers are also trying to create fully fleshed-out characters who arc over the course of the story. So they end up prioritizing that over making them funny. In the process, they’re fighting that character the whole script trying to make them act funnier than they are.

This is a comedy. You have to focus on laughs. Prioritize a hilarious character over a deep character. Cause when you do that, you don’t even have to try to be funny when you write scenes for that character. They just naturally say funny things. RJ naturally says funny things because he’s a lovable doofus who’s pretending to be an expert in something he’s a moron in. So every single thing that comes out of his mouth is funny.

Next we have conflict. When it comes to conflict, your bread and butter comedy comes from two-handers where the characters constantly bicker, like Deadpool and Wolverine. But conflict can also come in the form of anything that is out-of-balance. In this case, RJ is lying about who he is. So, in every scene, there’s potential for him to get caught. He’s always having to talk around things, which creates conflict.

But also we have some traditional conflict in that Sean is an a-hole and is constantly putting pressure on RJ to do what he wants, which, of course, hurts Izzy.

Next up we have mining the uniqueness of your premise. Too many comedy writers write a movie with a premise – say, two geeky teens build a robot version of a popular kid to make them popular at school too – then write up a bunch of jokes that have nothing to do with that premise. There will be jokes about aliens, about weddings, about prison, about sexual preference, none of which focus on the core concept’s conceit – that two guys have built a fake popular guy in robot form and are trying to use him to ascend the social hierarchy at school.

Cohen did it right. A good 75% of the comedy in I Can See You’re Angry is built around RJ pretending to be a therapist.

Finally, you have VOICE, which boils down to “a funny way to see the world and talk about it.” To understand comedic voice, watch comedians. Note, specifically, the STUFF THEY TALK ABOUT and HOW THEY DELIVER IT. Nate Berghatze likes talking about really basic everyday stuff, such as ordering DoorDash and hiding it from his wife. Meanwhile, Ryan Long has built his entire routine around political hypocrisy. Two very different subject matters.

Then you have delivery. Aziz Ansari is known for his energetic almost manic delivery style. Whereas Anthony Jeselnik speaks verrrrryyy slooooooow. He’s not afraid to pause for an eternity before he delivers a punchline.

Conveying voice in comedy scripts is similar. What do you like to talk about and how do you like to talk about it. The style in which you combine those two things should feel different from the way others do it. Cause if you sound like everyone else, telling the same jokes in the same manner, you won’t make readers laugh and everyone will forget your script quickly.

The only thing I didn’t like about I Can See You’re Angry was the last third of the script. There was something forced about going to Sean’s lake house. When you start to exert too much of your agenda on the plot, you lose that organic feel that made things so originally effortless. Organicness is especially important in comedy because the best comedy comes from natural situations.

But even with that, this was still a good script and it’s given me hope that, as long as a good writer is writing it, good comedy is possible.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[xx] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: A great comedy tool is exaggeration. And it’s simple to use. You just dial things up to a 1000. A trick on how to get the most out of it is to give an exaggerated line to someone who’s, otherwise, even-keel. It will then come out of nowhere, which is what makes it funny. When RJ is starting to make a lot of money as a therapist, he comes home to tell his mom that he’s finally going to change their lives for the better.

RJ:

Listen, Ma, things are about to

change around here.

LORRAINE:

If you take away my internet, I’ll

burn the house down with me inside.

I talk about exaggeration and other comedy tools in my dialogue book. If your dialogue is weak, DEFINITELY spend 10 bucks on my book. It will change how you write dialogue forever. That, by the way, is not an exaggeration. :)

Genre: Sci-Fi/Action

Premise: In a [sort of] post-apocalyptic world, a young woman teams up with a truck driver to traverse through a robot wasteland to retrieve her brother, who has been taken by an evil CEO and used as the brains of his internet company.

About: This was the 320 million dollar big swing from the Russo Brothers for Netflix and they brought back their Avengers screenwriters, Christopher Markus and Stephen McFeely, to help them write it. The movie is based on the iconic sci-fi art of Simon Stålenhag and stars Netflix superstar, Millie Bobby Brown, and worldwide superstar, Chris Pratt.

Writers: Christopher Markus & Stephen McFeely

Details: 2 hours long

I’m going to be straight up with you. This review’s going to get ugly. So, before it does, let me cast some compliments on The Electric State. Hollywood is obsessed with IP to the point of making a generation of moviegoers bored out of their minds.

Kids these days – at least the ones I know – don’t watch movies. And why would they? Studio films don’t have any soul left in them and I suspect they don’t have many people making them who actually love movies. They’re just doing a job. And when everybody is just “doing a job,” you get really bland product.

So I respect the Russo Brothers for, at least, trying something new. This is tricky material here. It’s a weird world with weird rules and a hard-to-wrestle-down mythology. I love that they’re trying to explore uncharted territory.

But there’s the irony.

Within that exploration, they went back and based almost all of their choices on the very IP they’re running away from. So the most original big budget movie of the year feels like the most cliched.

I still want Hollywood making weird sci-fi movies. But they have to bring in the kind of talent who can guide those movies to strong places. I used to think the Russo Brothers were that talent. But I’m not sure anymore.

It’s the 90s. Errr….. sort of. Because in these 90s, there was a robot uprising. Except I lived through the 90s and I don’t remember any robot uprisings. So I’m not sure what “period” we’re setting this movie in. Anyway…

A young woman named Michelle lost her younger brother in this robot war. But several years later, the government has squashed the rebellion and now keeps all robots inside designated fenced-off areas.

One night, a robot appears in Michelle’s backyard, just like E.T. (and I mean *just* like E.T. – as in they steal the exact same shot from that movie) and the robot claims to be Michelle’s dead brother. Well, sort of. You see, for reasons that are never made clear, the robot can’t speak normally. He can only speak in pre-programmed soundbites. Every other robot can speak normally. But not this one. Kind of convenient since, if he could speak normally, he’d be able to tell Michelle where his real-life body was and that would’ve cut 90 minutes out of the movie.

Anyway, Michelle pairs up with the robot to travel across the country to find her brother. Along the way, she’s forced to utilize the help of a truck driver named Keats. Keats is a rebel in that he often teams up with robots, even though robots are bad! So he and Michelle go into the Restricted Zone, despite it being littered with violent robots and, what do you know, win them over.

An entire team of robots then joins the duo in attacking Sentre, the big bad internet company that is holding her brother and is also the primary entity keeping the robots down. Michelle wants her brother back and the robots want their life back. Final battle. The end.

This is a great time to remind everyone that writing screenplays is a series of creative choices. One of the reasons it’s so difficult is that if you make the wrong creative choice regarding a couple of the key pillars in the story, there’s no way to save the script. You’re done.

For example, if you create a really unlikable main character, that creative choice is going to be in our face every single scene.

The problem with The Electric State is that it gets nearly all of the key creative choices wrong, starting with the setting. It doesn’t make sense to create a period piece about a time that never happened. I’ve never seen a successful movie that’s done this and I have no idea why anyone would think it’s a good idea. Because what you’re doing is you’re saying, “Nothing matters because none of this really happened.” If you would’ve, simply, set this 5 years in the future, it would’ve solved so many problems with the script.

The next creative choice The Electric State screwed up was the tone. If there’s one good lesson that came out of the superhero era, it’s that you don’t betray the source material. The further you stray from it, the worse the movie usually gets. So, by turning Stålenhag’s dark art into a plucky fun action-adventure movie, the movie never stood a chance. That wasn’t the story that Stålenhag intended to tell. And you can see that in every frame of the movie, which is fighting itself, trying to turn a cat into a dog.

Next up, the amount of borrowing in this movie is next-level embarrassing. From E.T. to Transformers to Guardians of the Galaxy to The Phantom Menace. It’s one movie after another where you recognize a character or a plot beat.

If you’re writing something and you’re constantly saying to yourself, “Yeah, it’ll be just like [that great movie]” and “Ooh, this character will be like that character from [that great movie.],” that’s BAD. Cause people are going to see those things and think of those movies, which are better by the way, than your movie. And the more you do that, the less your movie becomes your movie anyway. Instead, it becomes a pastiche of movies.

You get one clean rip off another famous movie and that’s it. But even then, you have to be careful. For example, you can’t base your hero off of John McClane in a terrorist action-thriller. The setup is too similar to Die Hard. But if you made a sci-fi movie about a cop on another planet, *that* character you can base on John McClane, because it’s a different genre and different setting.

What you don’t want to do is what Electric State did, which was make a sci-fi movie that borrowed from a bunch of other sci-fi movies.

On top of that, there was a whole lot of stuff in this script that didn’t make sense. Why couldn’t the E.T. robot – the one who says it’s got Michelle’s brother inside of it, speak when every other robot spoke?

How are we on a post-apocalyptic journey when the world is fine? Everything is running smoothly. Yet the movie is treating the journey like it’s happening in the “Quiet Place” universe.

And the movie didn’t even get the BASIC stuff right. The most basic thing you need out of a movie like this is to create an interesting unresolved dynamic between the two characters who are around each other the most – in this case, Michelle and Keats.

Yet I couldn’t tell you the first thing about their relationship. They have so little to actually discuss that they could’ve existed on their own separate journeys and nothing would’ve changed.

You have to build a compelling storyline into any character combination that has a lot of screen time together. There wasn’t a single issue between Michelle and Keats other than they occasionally annoyed each other. Compare that to Deadpool and Wolverine, who seemed to have generations of beef with each other that they had to bury in order to work together. That’s how you create a compelling unresolved relationship.

What happened to the Russo Brothers, by the way? I started to wonder if they were always this bad. But that Captain America sequel they directed was awesome. That was a great movie with great set pieces. And the two Avengers movies were good too.

But since then, they made The Gray Man, Cherry, and Citadel. And now this, their worst movie of all.

So, if this silly version of the story was so bad, what should they have done to fix it? Well, there was this sci-fi book published in 1972 called Roadside Picnic about how time stops and then when it starts again, humanity realizes that aliens came here and lived here for a long time before finally leaving. They’ve since left all these remnants and the book follows people who go looking for those remnants.

Just like Stålenhag’s work, it’s dark post-apocalyptic stuff and fits the same vibe as his drawings. I know the budget would’ve had to have been lower. But I’m positive the movie would’ve been better. Because even with 320 million, the Russos didn’t create one memorable set piece. Not one! In a big sci-fi action movie! That’s crazy. At least with the darker version, you could’ve explored better characters and thematic elements that connected with people. This was just silly garbage.

How bad are we talking here? Here’s how bad. If you told me you had Netflix and you wanted to know which movie you should watch tonight, The Electric State or that Meghan Fox is a robot Hand that Rocks the Cradle ripoff, I would tell you that you would have an infinitely more entertaining time watching the Meghan Fox movie.

[x] What the hell did I just watch?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the stream

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Use previous great movies as inspiration. But don’t steal actual elements from them. For example, if you have a time machine in your script, don’t make it a car, cause people are going to think of Back to the Future. Be inspired by the broad strokes, never the key individual elements.