Search Results for: F word

I don’t give ratings like this to amateur scripts (or any scripts these days) very often. But I’m giving one today!

Amateur Friday Submission Process: To submit your script for an Amateur Review, send in a PDF of your script, a PDF of the first ten pages of your script, your title, genre, logline, and finally, why I should read your script. Use my submission address please: Carsonreeves3@gmail.com. Your script and “first ten” will be posted. If you’re nervous about the effects of a bad review, feel free to use an alias name and/or title. It’s a good idea to resubmit every couple of weeks so your submission stays near the top.

Genre: Drama

Premise: (from writer) A young Jewish woman in occupied France escapes the Nazis by changing places with a shop owner. But as her love grows for the other woman’s husband and child, so does her guilt.

About: This is…. Amateur Week SMACKDOWN – 5 scripts, all of which have been pre-vetted by the SRF (Scriptshadow Reader Faithful), vie for the Top Prize, an official endorsement from whoever the guy is who runs this site. Good luck to all!

Writer: Michael Whatling

Details: 111 pages – NOTE: This is a NEW DRAFT from the one originally posted on Amateur Offerings, with notes incorporated from those who read it.

Natalie Portman for one of these two hot female roles?

Natalie Portman for one of these two hot female roles?

Amateur Week Smackdown is coming to an end. Going into today, Tuesday’s entry, Ship Of The Dead, is the clear leader. It didn’t quite garner a “worth the read,” since its second half didn’t live up to its first. But it was the most marketable script, and the easiest to tweak, should someone want to buy it and turn it into a movie.

With that said, I’d been saving Patisserie for last because this one had gotten the best reception from all of you guys. Word on the street was that even a French A-list actress requested the script for a read. So if all else failed, I had a feeling Patisserie would save us from a trip to The Burning Fire Pit Of Forgotten Screenplays. Let us engage our Google Translation apps, jump on the Chunnel train, and dip our heinies in a little croissant butter. Time…..FOR SOME PATISSERIE!

It’s 1941. France is occupied by Germany. This means that every French town is infested with Nazi soldiers. Soldiers who are amping up their search for Jews. This is where our story begins. A group of Jews have been rounded up and marched through the streets of a small town, chained together, for everyone to see and understand who’s in control. These Nazis want the townsfolk to know that with the flick of a wrist, they could be heading to a concentration camp near you.

Emilie is one of these Jews. She’s stuck on the line. But when a fortunate trip by one of the older men occurs, it provides her with an opportunity to escape. So she darts over to a nearby Patisserie and scurries inside, all while an owner of the shop, the beautiful and innocent Mireille, is too stunned to say or do anything about it.

When the Germans realize they’ve lost the girl, they start freaking out. Realizing that they can’t show up to the camp one girl short, they grab Mireille, who somewhat resembles Emilie, clobber her unconscious, and go on their merry way, numbers intact.

When Mireille’s husband, Andre, comes home, he finds former Jewish prisoner Emile hiding in his shop, which he’s a little more than confused by. But Andre’s a nice guy, so he gives Emile some food and lets her play with his 2 year old son while he waits for Mireille to come home. Of course, Mireille doesn’t come home. Not that day, not the next day, and not the next.

Andre’s confused at first, then angry, and then obsessed about his wife’s disappearance. Unfortunately, nobody will talk to him about what happened that day. Nobody wants to piss the German soldiers off. So they tell him to shut up and stop making trouble. Eventually, Andre comes to grips with the reality that his wife isn’t coming back. And slowly, almost by default, Elise assumes that wife/mother role in the family, even taking Mireille’s official identity.

It doesn’t take long for the Nazi soldiers to get suspicious, particularly a snide little rat named Egger, who takes a liking to both Elise and Andre’s baked goods. He notices that Andre and Elise don’t look right together, and lingers at the shop after his nightly shifts, asking questions that neither of them can easily answer. We get the feeling that sooner or later, this is all going to blow up. The question is, on which side will the casualties lie? And will Andre ever see his real wife again?

About midway through Patisserie I let out a big sigh, pushed my computer away, and took a drink of water. This is a longstanding cue for Miss Scriptshadow to look at me and say, “Good or bad?” I needed to think about that question. It wasn’t a simple answer. I finally offered a reserved, “Good.” Then I paused. “But boring good.”

I wasn’t aware what I meant by that at first. I mean, I don’t think there’s any question that Patisserie is the best-written script of the week. The writer transports you to a place and time via a mastery of prose and atmosphere that leaves most writers in the dust. Good writers seem to have this ability, where you’re not even aware you’re reading a script while you’re reading it. It all flows so naturally. It all feels so real.

But still, even though I was enjoying Patisserie, there was nothing jumping out at me. It was all very understated. “Boring good” might actually be a harsh assessment. But it was definitely the kind of good that’s hard to get excited about. So yeah, I wanted to finish the thing, but I didn’t NEED to finish the thing. And that’s an essential difference between a good script and a great one.

Well, not so fast, Carson. As I entered phase 2 of the script read, something happened. Every five pages, the script got better than the previous five pages. And I’ll tell you when I realized I had something special – it was the scene where Egger (huge spoiler) lets Andre and Emilie know he knows their secret, so they kill him. It was just a really tense well developed scene with tension and suspense and dramatic irony and surprise. Whatling had done a great job with all the previous Egger visits setting this moment up, and the result was this victorious feeling for finally taking down one of the bad guys, mixed with horror as we feared the repercussions of the act. From that point on, I was president of the Patisserie Fan Club.

But there’s nothing that could’ve prepared me for the climax. Now I’m going to get into some major spoilers here so I recommend you read the script before continuing. But here’s why I was so revved up about this. I always say that if you REALLY want to give us a character to remember, give them an impossible choice. Give them a choice where there is no right answer, and where the stakes for the choice are sky high. And if possible, place that choice during the climax.

When we’re looking at Mireille screaming at Andre in the middle of the street, to please tell the German officers that she’s his wife, I mean… I had to do the “Readjust.” The “Readjust” is when you sit straight up, make sure you’re totally comfortable, then go back to reading. Bad scripts never get the Readjust. I remain slouched back the whole time during a bad script.

But even WITH that piece of advice I so often preach, I couldn’t believe what Whatling did with that final chapter. A German officer brings Mireille over to Andre and says she’s claiming that Andre is her husband, and that Ellie is a Jew. With Ellie standing next to Andre, the soldier demands that he tell him which one of these women is his real wife. I honestly had no idea what he was going to say. It was one of the most tension-filled climaxes I’ve ever read. It was that good. And it’s that scene that pushed this up to an impressive for me.

And you know what else made this an impressive? It’s another thing I always preach. You want your main characters to be the kind of characters that actors would die to play. Make them Academy Award worthy characters. I’m not kidding with what I’m about to say. If this script gets into the right director’s hands? If the right people are making it? I could see it garnering TWO Academy awards, one for the lead (Emile), and one for supporting (Mireille). Female actresses just don’t get the opportunity to play characters like this very often.

But there’s a lot more to celebrate here. I love how the entire movie is built on one of the most dependable screenwriting tools there is – dramatic irony. We and Emilie know what Andre does not – that his wife was taken by the Germans. And it was Emile’s fault! This provides an undercurrent of tension and suspense throughout the entire script, as we’re wondering when this information is finally going to be disclosed to Andre, and how.

And Egger – what a brilliant villain. One way I know I’m dealing with a good writer is when the villain isn’t an over-the-top evil asshole. Egger was a coward. A conniving slimy two-face who smiles and pretends he’s your best buddy, all while stealing from you. These are the villains that really stick with audiences – the ones we truly want to see go down. And boy were we happy when Egger went down.

Besides the slow first half, I really only have one complaint. (spoiler) I don’t think Emilie should give herself up in the end. When Andre tells the officers that Emilie is his wife, and he’s walking away with Mireille pleading to him on her hands and knees, I think that’s the end of your movie. It doesn’t get any more powerful than that moment. And to end on that…holy shit would that have everyone talking as they leave the theater – creating the kind of word-of-mouth that only much bigger movies with much bigger budgets and marketing campaigns can achieve. Something about Emile going back to give herself up felt like an extra ending to me.

That’s my one suggestion. But this isn’t a script that needs a lot of suggestions. It’s freaking that good!

Script link: Patisserie

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[x] impressive

[ ] genius

AMATEUR SMACKDOWN WEEK WINNER: Patisserie!!!

What I learned: There’s something about a villain who smiles while he steals from you that always gets audiences. A person who charges in and demands you give him money or he’ll shoot you in the face is boring. If that same person pals around with you for half an hour, then gently implies that for protection, you might want to fork over 30% of your paycheck? We will always hate that character more than the Obvious Guy. That’s why Egger was so genius here. He WAS that character.

Why this script SHOULD be purchased: Look, there’s no question this is a tough sell. However, there’s always going to be a market for World War 2 films. You should have no problem attaching two well-known actresses to this script, which should get you financing, which should get the film made. This ain’t going to be a The Purge return on investment. But it could be one of those “little engines that could” that battles for Academy votes come the end of the year.

Amateur Submission Process: To submit your script for an Amateur Review, send in a PDF of your script, a PDF of the first ten pages of your script, your title, genre, logline, and finally, why I should read your script. Use my submission address please: Carsonreeves3@gmail.com. Your script and “first ten” will be posted. If you’re nervous about the effects of a bad review, feel free to use an alias name and/or title. It’s a good idea to resubmit every couple of weeks so your submission stays near the top.

Genre: Sci-fi/Noir

Premise: (from writer) In the year 2068, a rough and tumble Detective who moonlights for organized crime is forced to solve a series of crimes wherein android prostitutes have been killing their clients, before a zealous US Attorney succeeds in his mission to destroy him.

About: Rarely do I review an amateur script if it’s not Amateur Friday, but I have an unwritten rule that if you send me a kick-ass query letter or have the most amazing unbelievably awesome premise ever, I will review your script right away. Such was the case with James Thoo, who sent me this hilarious query letter, which I’ve included below.

Writer: James Thoo

Details: 101 pages

Hi Carson,

So this is the first time that I’ve had to come up with two stories to sell one screenplay. One for the screenplay itself, and one for me and the process behind the writing of the screenplay, to get you to read it. I think I have both though, so here goes.

I’ve actually sold work before. Bear with me though, because I’m still pretty sure I qualify for Amateur Friday. Mostly because I am a total amateur now with zero residual ties to the film industry remaining. I started out in film (ish) as a News Editor for JoBlo.com, which is a pretty major movie news website. I got that job when I was 18. People seemed to really dig my voice before I was fired two years later for taking a few too many jabs at Eli Roth – whom I loath and whose films I avoid like I would avoid fraternity rape – who in turn emailed my boss to tell him that he was tired of me “being a persistent asshole to him.”

After that I was approached to write a screenplay by a small studio in LA, who optioned it, but never made it. I was sad about this for a while. That was kind of parlayed into being hired to write a modern adaptation of Shakespeare’s Othello for a Malaysian film studio (where I went to school; my dad moved around a lot). I had some meetings set up in LA but I declined them because I really wanted to do something in Malaysia. I had gross delusions of grandeur wherein I changed the face of the infant film industry over there and local government declared a James Thoo day and elderly women and small children alike high-fived each other amid tears of pure joy. Virgins were offered up and I chose which ones I was interested in with the flick of a cane fashioned for me from pure gold and unicorn bones. I’m sure you can imagine.

So I signed to make the Othello movie. Which would end up being perhaps not the, but certainly one of the biggest crimes perpetrated internationally, ever, and not just in film: in general. Good lord was this film an abomination.

As I mentioned, the film industry in Malaysia isn’t very developed and so there are a lot of restrictions. One of which is on run time, which shouldn’t really be a problem, but quickly becomes one when your director (who has final cut) has been subsisting for the past month on a steady diet of marijuana, self-praise and Terrence Malick films. As such the film was an unmitigated disaster. Back story and some pretty substantial plot points were extradited for inconsequential, self masturbatory lingering shots of snakes and foliage and shit. The producer also pulled a Street Fighter: The Legend of Chun Li and added in some voice-over that he had written himself, which was also added to all promotional materials, because, you know, why not?

Beyond all reason the film actually won a couple of awards and got an extended cinematic run but I was so disillusioned with the whole thing that I tried to take a page out of Tony Kaye’s book and change the writing credit to Humpty Dumpty. When I couldn’t make that happen I never wrote again. There was a funny instance of me picking up a film magazine one day and flicking to the review section where I went straight to the verdict and saw four out of five stars. I was pretty proud. And then I glanced over at the next page and saw Alvin and the Chipmunks. Five stars. There’s probably some similar stories to mine floating around, but I should point out that all of this happened when I was 22 years old. I don’t think that there are many people you meet who effectively, completely burnt out as writers by the age of 22. That was over 5 years ago now.

So yeah, I’ve been working since, as Editor in Chief of an online news portal in Malaysia, which consists largely of curating news aggregation and editing for a team of mongoloids who wield the english language with the kind of accuracy a drunk shows a urinal. These guys are like the anti-grammar. It is mind numbing. Up out of nowhere, 6 months ago I started writing again. I had a sudden bout of genuine inspiration. And I found my passion again. Maybe it is totally misplaced and whatever minor talent I once had is long gone, and whatever I came up with this time around is total garbage, but here it is nonetheless. I’d truly appreciate it if you would take the time to read my screenplay and then decimate it publicly on your blog.

In all honesty, I’m not an every day reader of Script Shadow, but I do check in a couple of times a week. I really think you’re doing a wonderful job, and I hope my relative lack of dedication to your lessons does not preclude me from writing a script that you appreciate. Or don’t hate. Let’s see…

You can’t read a query letter like that and not think, “This guy’s gotta be good.” I mean he obviously has a natural ability to tell stories and be funny, and if you have that, you’ve got a shot. But then I opened the first page of “Keep Us Safe.” My heart sank. James’ intro page suffered from “Wall of Text” syndrome. It’s a disease that’s commonly found in young writers who are still learning the craft. Their main source of reading entertainment up to this point has been books, so they start off writing their scripts like books, packed with way too much description.

And readers HATE this. They hate it. I hate it. Because it’s going to tack 45 more minutes onto my reading time. Which would be fine if those minutes were spent word-smithing together an enhanced story. But 80 out of 81 times, the opposite is true. The excessively long passages gum up the story, making the script the literary equivalent of the 405 at 6pm on a Friday. However, I still had some confidence in James. I knew he could write. Yeah, the first page was wordy, but it wasn’t “I can’t string a sentence together” wordy. The descriptions painted a strong picture. So I figured – Let’s still give this James guy a shot, Carson.

The year is 2068. The location is Los Angeles, CA. Shades of Blade Runner abound. Also some shades of A.I. In fact, if I were to describe “Keep Us Safe,” I’d say “It’s Blade Runner meets A.I meets I-Robot.” Tommy Patterson is a crooked cop for hire. The man can be bought for a 5 dollar footlong (or a 50 dollar footlong in the year 2068). However, despite being described as such, he seems to be very un-crooked in his policing – as we meet him chasing down a nasty drug dealer. Which was confusing. If you’re introducing a character who’s dirty, you probably want to show him doing something dirty. And if Patterson IS doing something dirty here, it isn’t clear.

Afterwards, Patterson’s told by his boss, Police Chief Martin Deinard, that the newspapers know he’s dirty and are going to destroy his reputation. Which means Deinard has to demote him (I was a little unclear on why he didn’t just fire him), giving him, in his words, the worst jobs in the precinct. Strangely then, Patterson’s placed on homicide for a string of cop murders perpetrated by a rogue android prostitute. I don’t know about you, but that sounds like the coolest assignment ever!

Patterson’s case takes him to the maker of these prostitute-bots, Lux Kubotu Robotics, where he learns that a high-profile employee recently quit. It’s the CEO’s belief that the employee may have implanted some code that made the robots killers. So he bounces around from bars to nightclubs, talking to a lot of seedy folks, trying to trace down this dude, eventually learning that someone HE knew actually sent this robot into the red light district to take down Patterson himself, who was known to frequent the area. Patterson will have to go back into his own ranks, then, to take this asshole down.

I’ll be the first to admit this summary may not be 100% correct but that’s only because I couldn’t always tell what was going on. And this takes us back to all that text I was complaining about earlier. You see, many writers believe that writing a ton of description gives the reader MORE information. However it often works the opposite way. The reader’s focus starts drifting. Or meaningless things (like the smell of the air) are highlighted, imposing on the reader that he doesn’t need to read all the text as it doesn’t contain relevant information, resulting in him starting to skim. Or the plethora of words start to get jumbled around, confusing the essence of what the writer is trying to say. Let me give you an example. Here’s the beginning of an early scene in the police chief’s office…

Patterson slumps into a leather couch that occupies the far corner of the office. He rests his head in his open palm and leans into the shadows.

On an extravagant mahogany chair in front of the main bureau sits a man, broad, rough around the edges but trying to make clean: D.A. HENRY CAHILL. He turns his seat to face Patterson, who nods familiarly in his direction.

POLICE CHIEF MARTIN DEINARD is all business. He wears a flawless pinstripe suit with a transparent brace around his neck the catches hair as his PERSONAL BARBER trims at the grey, close around his head.

He stands by the window of his office and looks down at the city. He sighs and turns to Patterson with a TABLET PC in his hand. The Barber follows his every move. He tosses it into his lap and Patterson caches it instinctively, twisting it to read what is being shown.

The image rotates to fit the screen and he sees a middle-aged man, thin, strong, definite jawed, no-nonsense, like he was carved from granite. If anything, maybe like a younger more idealistic Deinard himself.

Holy Word Explosion Batman! Here we have five huge paragraphs (note that the paragraphs have been thinned out due to the format change: they are 3, 4, 4, 5, and 4 lines respectively in the script) to set up a scene. We never need this many paragraphs to set up a scene unless extremely complicated and/or relevant things are going on. Honestly, this is how I would rewrite it…

Patterson slumps in a leather couch. He’s surrounded on either side by D.A. HENRY CAHILL, a slimy crooked type, and POLICE CHIEF MARTIN DEINARD, who’s being tended to by his personal barber.

The chief stares out at the city, cutting off the barber momentarily to hand Patterson a tablet PC. On it is a middle-aged man, a no-nonsense type, who looks like Deinard may have looked like 20 years ago.

Now I understand that you want to convey SOME atmosphere and description in your writing, but you want to do so in moderation because this is screenwriting, not novel writing. Check out The Equalizer or When The Streetlights Go On to see writers convey atmosphere yet still keep their prose sparse.

Because “Wall Of Text” Syndrome has a trickle down effect. It leads to what’s known as “Reader Mind Slip.” This is when a reader’s mind gets overloaded with unimportant information, so they stop paying attention. When this happens, they can’t keep up, as they’re constantly having to re-read paragraphs that they only sorta grasped the first time, which leads to frustration, which leads to them eventually saying “Fuck it” and charging through, even when they don’t entirely understand a scene. From that point on, they’re operating in “Murkyville” territory. They sort of understand what’s going on, but don’t get all of those finer points you’ve meticulously plotted in there. Which is why it’s so important to keep your prose sparse and only tell us what we need to know. You want to avoid “Reader Mind Slip” at all costs.

There are other problems here as well. The story played out too predictably. I felt like I’ve seen it before. The love story comes in too late, making it feel like an afterthought. But if I were James, I would just focus on thinning out his prose for now. Learn how to say a lot more in a lot less. Because obviously, James can write. I mean he can string a sentence together. Even though the writing was thick, it was never bad. And a lot of the dialogue was right up there with professional-level dialogue. But none of that stuff matters unless the story is easy to grasp, and right now all this text is getting in the way.

Also, I have a personal plea for James. Write a comedy script! From your e-mail, you obviously have the chops for it. It seems like it suits your sensibilities better anyway. In fact, write about that experience you had going to Malaysia. It sounds hilarious. I’ll be the first in line to read any comedy you write. And don’t let this review get you down. You seem a bit sensitive. You obviously have talent, I just think you need to tweak your writing approach a little. I wish you luck my friend.

Script link: Keep Us Safe

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Your query letter is a key part of your marketing. The tone should reflect you, but more importantly, your script. So if you have a heavy drama, be professional and serious in your query. If you have a comedy, be funny! By the same token, try not to act one way in your query then give a script that’s completely the opposite. After James’ hilarious query, I was hoping for a comedy. So it was a little confusing getting a dark sci-fi script.

What I learned 2: Beware pages that look like walls of text. Beware multiple pages in a row that look like walls of text. But most importantly, beware of a FIRST PAGE that looks like a wall of text. It will put your reader off right away.

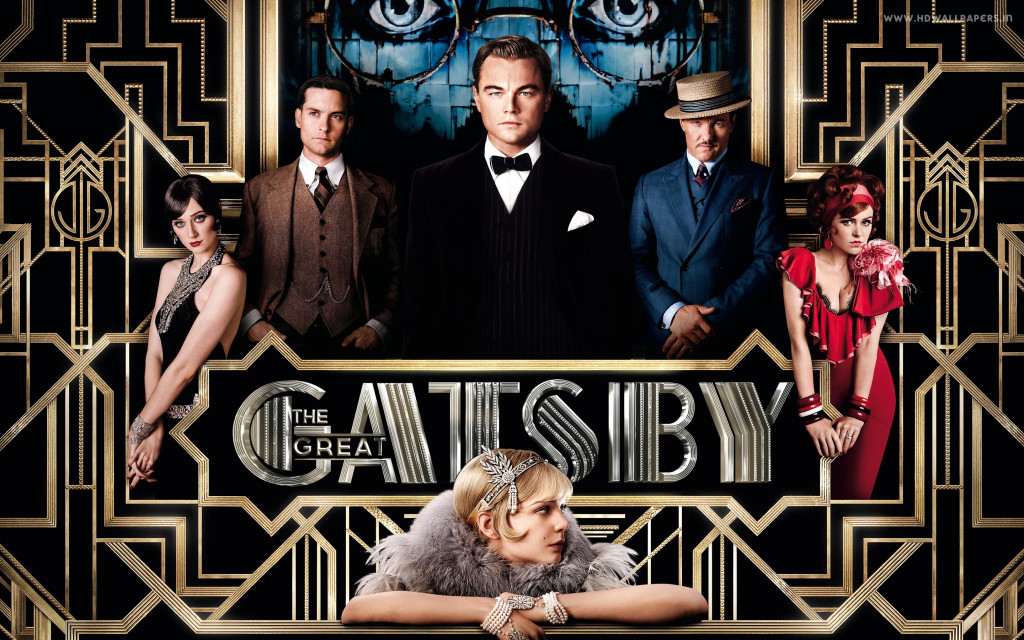

The Great Gatsby had the best use of 3-D I’ve ever seen. But how many dimensions did the actual storytelling have!?

Genre: Drama/Period

Premise: Set in the 20s, a former writer moves next to one of the wealthiest men in New York. When the man, a shadowy figure known as Jay Gatsby, invites him to one of his famous parties, he finds his life forever turned upside-down.

About: So if the frustration of coming up with a title for your script is beating you down, note that as far back as 1925, writers were still battling the issue. Believe it or not, F. Scott Fitzgerald was set on calling his novel “Trimalchio in West Egg.” It was only after friends convinced him that the title was non-specific and un-pronounceable that he turned to the title we know today. Something tells me had he not made that choice, none of us ever would’ve heard of the novel. Which makes me wonder: How many unknown classics are out there because of bad titles? Speaking of, here’s a little known fact: Gatsby was not a hit when it was first published. It was actually a bomb, leaving Fitzgerald to die believing he was a failure. It was only during World War 2 when schools started using Gatsby in their curriculum that it went on to obtain the status it has today. Baz Lurman and his longtime writing collaborator Craig Pearce adapted the novel for the screen.

Writer: Baz Luhrman and Craig Pearce (based on the novel written by F. Scott Fitzgerald)

Details: 2 hours and 20 minutes long

I love this shit!

A non-comic-book, non-franchise, non-sequel, non-YA-novel-adaptation, non-Johnny-Depp, non-Pixar CHARACTER PIECE comes out in the most competitive part of the year and cleans up 50 million at the box office. Now THAT is encouraging. It makes me believe in the purity of the screenplay again. True, it did have one of the biggest movie stars in the world and the script is an adaptation of a book. But The Great Gatsby is hardly what I’d call a surefire hit. It’s a character study from the 1920s!

Now believe it or not, I’ve read The Great Gatsby. I realized a few years back that there was an off chance I might run into a literary snob at a party who saw screenwriting as an inferior type of storytelling, and this literary jerk-off might corner me with the inquiry, “And what book have YOU read recently, Carson? Or do you even READ books?” In which case I could answer, “Oh, I actually recently read The Great Gatsby. I try to revisit a classic every month or so.” And then I’d triumphantly march off, leaving a bunch of startled partygoers in my wake, amazed at my unending literary know-how. This moment hasn’t happened yet. But it will. Oh trust me – it will.

Now for those of you who ignored your reading assignments in high school or don’t revisit the classics every month like I do, The Great Gatsby is about this guy named Nick Carraway, a writer turned bond trader who moves to Long Island. While Nick is a man of modest means, he seems to have tons of friends who are uproariously rich – like his cousin Daisy, Daisy’s bestie Jordan, and Daisy’s husband Tom (a polo star).

Coincidentally, Nick’s shack is located next to another rich man, Jay Gatsby. Though he holds the biggest parties in town, nobody seems to know who Gatsby is or what he looks like. Well, one day the mysterious Gatsby sends an invitation to Nick to join one of his parties, and despite senators and mayors and celebrities and sports stars attending, Gatsby only seems interested in speaking with Nick.

Fast-forward a bit and we find out that the reason Gatsby is so keen on gaining Nick’s friendship is his secret past with Nick’s cousin, Daisy. It appears the two fell in love many years ago when Gatsby was a poor nobody soldier. The two couldn’t be together because of his lack of wealth, though, so Gatsby went about amassing as much wealth as possible over the last half-decade (most of which came from underground bootlegging) and has come back bigger and richer than everyone in town, all in the hopes of snagging Daisy, a task that’s become tricky seeing as she’s now married. In the end, the lives of all of these rich (and not so rich) folks will collide (literally) in an explosive finale, one in which Daisy will decide who she wants to spend the rest of her life with, Tom or Gatsby.

There is so much screenwriting shit to talk about here, I’m not sure where to begin. Let’s start with this: Gatsby should not have worked as a screen story. It does too many things that should sabotage a narrative, the most egregious of which is having its main character be the least interesting character in the movie. Yes, Nick Carraway doesn’t have jack going on. He’s meager, insular, reactive, boring. The man’s got nothing going on in his life of interest. No intriguing backstory or flaw to talk about. Yet he’s the one taking us through this tale. What’s the deal?

The deal is that he’s a “narrator,” a device that worked quite nicely in the 1925 literary world, but which has since lost its luster. Why? Because at some point someone realized that a narrator who has absolutely nothing to do with anything is probably not main character material. If Gatsby was being written today – ESPECIALLY as a spec – undoubtedly the story would be told through Gatsby’s eyes. This is the man enduring all the interesting shit in the movie. This is the man being active, making things happen. He has the most character development, the most layers. Think about it. He’s the most powerful man in New York, yet the most insecure person you’ll ever meet. He’s draped in the most expensive clothes and vehicles and houses you’ve ever seen, yet he’s unable to see himself as anything other than a penniless nobody. He projects a fantastic life, yet it’s all a lie. He has all this money, but it was all made illegally. It’s no wonder this book has lasted as long as it has. Gatsby is the definition of a fascinating character.

Here’s where the movie ran into trouble though, and I’m not sure if it was entirely the writing or the actors portraying the characters– almost everyone here wilts in the shadow of Gatsby. There’s Nick, of course, who’s only there to offer up exposition. There’s Tom Buchanan (Joel Edgerton) who couldn’t be more of a cliché asshole husband if he tried. And Carrie Mulligan….hmmm, I’m starting to think her time is up. There’s something very…forgettable about her. She has these beautiful sad eyes, which make you want to pick her up and carry her to safety. But she can’t seem to parlay those eyes into any kind of charismatic or memorable performance.

The character who had the most potential within the second string was Jordon, Daisy’s friend, who was always leading Nick around everywhere. However, Fitzgerald created this strange dynamic by which Nick was never allowed too deeply into these characters’ lives, preventing any sort of compelling relationships to occur. Even when the opportunity presented itself, Nick always seemed to pull away from it, as if to say, “Oh, wait, you want me to actually be IN the movie? No, thank you. I’m just going to watch from afar.” It was one giant tease watching him walk around with the flirty Jordan over and over again, only for NOTHING to happen. It almost convinced me that Nick was asexual.

For those interested in discussing structure, Gatsby does offer some talking points. Just the other day we were talking about the “mystery box.” Well, much of Gatsby is driven by the mystery box. The first mystery box is Gatsby himself! What does he look like? Why does he hide in his own parties? Who is this man?? People are constantly talking about him in hushed whispers. There are rumors, guesses, assumptions, all different, all in constant flux.

Once we meet Gatsby, there’s another mystery box (remember – always replace an answered mystery with a new mystery box!). Gatsby seems to want something. We just don’t know what. Eventually, it’s revealed to be Daisy. Finally, there’s one more mystery box, and that is: How did Gatsby accumulate his wealth? This is a big one because the man seems to be one of, if not the richest, men in New York. Everyone wants to know how he became this way.

After all the boxes are opened, the writers realize they need a final force to drive us to the end of the story. Instead of another mystery, however, they choose a goal – for Gatsby to steal Daisy away once and for all, but more specifically, for her to tell Tom that she never loved him. It’s sort of an awkward goal and I’m not quite sure if wanting someone to say a string of words is weighty enough to drive a climax, but it does end up working, as it leads to the most powerful scene in the movie, when Gatsby and Tom battle over Daisy in a steamed up New York apartment.

More importantly, from a screenwriting perspective, there’s something to learn here. You can drive your story forward with a series of mysteries, then insert a late arriving goal to take the story home. Not every movie is going to be Raiders of the Lost Ark, where the goal is established right away. A “late arriving goal” is perfectly fine, as long as you find other ways to keep your readers interested before we get there (in this case, using a series of mystery boxes).

It would behoove me not to mention the amazing use of 3-D here, the best use of it I’ve ever seen. Not so much from a technical standpoint, but from a motivation standpoint. All these other movies seem to use 3-D for the wrong reasons, as a way to make explosions seem more explosion-y. Here, it’s used to bring us back to the early 20th century. I felt like I was inside this world, however exaggerated it may have been. The costumes, the set design, the shots of the cities – it’s all immaculately put together and we’re pulled inside that world, almost to the point where we feel like we could touch it via three dimensions. Add a smashing soundtrack to the mix and this was one of the best pure cinema-going experiences I’ve had in a long time. My only complaint is an over-long second act (did this really need to be 140 minutes long??). But the pure spectacle on display almost made you forget about it.

Script

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

Movie

[ ] what the hell did I just watch?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[xx] worth watching in the theater for sure!

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: A great reminder that many of the most fascinating characters in history are those steeped in irony. Gatsby is powerful but insecure. Successful but a crook. Irony often creates struggle inside a character, and struggle within one’s self is often the most interesting struggle for an audience to watch.

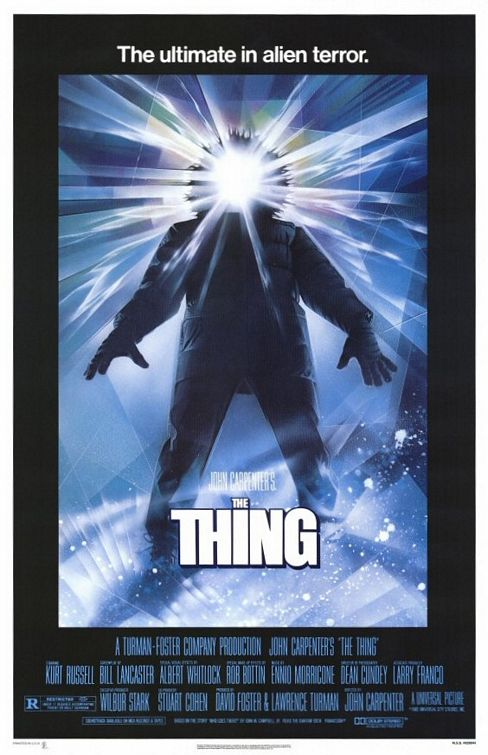

The Thing is probably one of the scariest movies ever made. People haven’t always seen it that way since it’s not set strictly in the horror genre. But man, I remember watching this film as a kid and being freaked the hell out. When the spider-legs grew out of that man’s decapitated head and began walking around? That image is still burned into my brain. The screenwriting situation behind “The Thing” is kinda interesting. Bill Lancaster, the writer, is Burt Lancaster’s son. His credits include only 2 other movies, “The Bad News Bears” (the original), and “The Bad News Bears Go To Japan.” He also wrote the Bad News Bears TV series. That was back in 1979. He didn’t write anything after that and died of a heart attack at the age of 49 in 1997. I’m baffled as to why Bill didn’t write anything else when he showed a clear mastery in two completely different genres. Was this his choice? Hollywood’s choice? Did the pressures of having a famous Hollywood father play into it? I’d love to know more. But since I don’t want to depress the hell out of all of you, I’m going to break down The Thing.

1) Use Clip-Writing to spice up action sequences – Clip-Writing is when you write in clips, highlighting primary visual queues. Clip-Writing can be very effective in action scenes as it helps the reader focus on the centerpieces of the battle, fight, or chase. We see it in The Thing when a Scandinavian crew has followed an infected dog into an American base.

CLOSE ON A .357 MAGNUM

As it efficiently breaks through a windowpane and into the cold. A steady hand grips it firmly.

THE SCANDINAVIAN

Getting closer. Kablam! Suddenly, his head jerks back. He falls to his knees and then face down into the snow.

NORRIS AND BENNINGS

Stare blankly, but relievedly at the fallen man. The dog whimpers in pain.

2) If Dialogue isn’t your strong suit, look to show more than tell – There’s actually some good news if you’re not a great dialogue writer. It means you’ll be forced to SHOW rather than TELL us things, which is really what you should be doing anyway. I noticed from reading and watching “The Thing” that a lot of the dialogue from the script was cut. Carpenter chose instead to focus on the visuals and the actions. For example, there was a scene early in the script where they’re walking to the helicopter and there’s a lot of explanation going on of what they’re doing. Carpenter cut a lot of that out, focusing instead on them simply getting in the helicopter and leaving. We know what’s going on. We don’t need a big long talky scene to explain it.

3) Only have your characters speak if they have something to say – This is an extension of the previous tip, and an important one. Your characters should be talking because they have something to say, not because you (the writer) have something to say. You might want to write a big monologue about how your character lost his sister or your opinion on the earth’s eroding ecosystem. That’s great. But would YOUR CHARACTER say that? I don’t think enough writers really ask that question. There’s nothing worse than reading a bunch of words coming out of a character’s mouth that you know are only there because the writer wanted to include them.

4) ALWAYS WORKS “There’s something else you should see” – I don’t care how bad of a movie or script it is, variations of this line ALWAYS work: “There’s something I need to show you.” You will have the audience in the palm of your hand until you show them what that character is referring to. With The Thing, that line brings us to a giant mutated gnarled mass of a body. If you can milk the time after the statement until the actual reveal, even better, as our anticipation will grow.

5) MID-POINT SHIFT ALERT – The Thing has a great midpoint shift. The first half of the script is about the discovery of this alien organism invading the base. Remember, a good midpoint shift ups the stakes. So the shift here is when they learn that any one of them could be the alien entity. It’s no coincidence that this is when The Thing really gets good. A great mid-point shift will do that.

6) Carefully plot how you reveal information – Always be aware of what order you reveal your information in and how that affects the reader. One omission or one addition can completely change the way the next 30 pages reads. For example, here, the movie starts with an alien ship crashing. This gives us, the audience, superior knowledge over the characters. We know they’re dealing with an alien. This means we’re waiting for them to catch up. Now imagine had Lancaster NOT included this opening shot. Then, everything that happens is just as much a mystery to us as it is the characters. I don’t want to rewrite a classic, but the opening act may have been a little more exciting had we not received the spaceship information. We’d be equal amounts as baffled and curious as the characters.

7) SHOW DON’T TELL ARLERT – In the script, the characters have about a page and a half dialogue scene talking about how if the alien makes it to civilization, it could destroy the entire world. It’s not a bad scene. But they replaced it in the movie with a simple shot – Blair staring grimly at a computer chart that states: If the organism reaches one of the other continents, the entire world population will be contaminated within 27,000 hours.

8) Foreplays not Climaxes (Aka Don’t reveal all your fun stuff right away) – I see this all the time with amateur writers. They’re so excited about the cool parts of their script that they can’t wait to write them! So when it’s time, they drop all their reveals on you simultaneously, like a giddy kid who’s been waiting to tell you about his trip to Six Flags all day. For example, the Americans find the Norwegian crew’s video tapes from their destroyed camp and start watching them to figure out what happened. An amateur writer might have slammed us with all the crazy reveals immediately (alien ship, alien body). But Lancaster takes his time with it, showing the Norwegians having fun on the tapes, basically being boring. It isn’t until a handful of scenes pass that we see the Norwegians blow up the ice and discover the alien ship. If you throw all your climaxes at us at once, we get bored. Give us some foreplays beforehand.

9) Lack of Trust = Great Drama! – Once characters stop trusting each other, the drama in your story is upped ten-fold. You now have characters who are guarded, suspicious, not saying what they mean, probing. This ESPECIALLY helps dialogue, since it’ll create a lot of subtext. Whether it’s because they think another person is secretly a shape-shifting alien or because they think their husband cheated on them with their best friend, it’s always good to look for situations where characters don’t trust one another.

10) Use Cost/Value Ratio to determine whether a scene is necessary – There was an entire cut sequence in The Thing where the dogs escaped the compound and MacReady went after them with a snowmobile. It was a nice scene but it wasn’t exactly necessary. Producers HATE cutting these sequences after they’ve been shot because it’s cost them millions of dollars. Which is why they try to cut them at the script stage. This is where you can benefit from pretending you’re a producer. Simply ask yourself, “Is the VALUE of this sequence worth the COST of what it would take to shoot?” But Carson, you say, why should I care about the budget? I’m not the director or producer. That’s not the point. The point is, you’ll start to see what is and isn’t necessary for your script. If you say, “Hmm, would I really pay 5 million bucks to shoot this chase scene that doesn’t even need to happen?” you’ll probably get rid of it, and your script will be tighter for it.

These are 10 tips from the movie “The Thing.” To get 500 more tips from movies as varied as “Aliens,” “When Harry Met Sally,” and “The Hangover,” check out my book, Scriptshadow Secrets, on Amazon!

So over the last few weeks, you guys have seen me bring a certain term up time and time again: CLARITY. Or, more specifically, lack there of. Clarity isn’t as sexy to talk about as character arcs or the first act turn, but unclear writing is a way-too-common problem for beginners and low intermediates, particularly because they’re not aware it’s a problem in the first place. Tell them you didn’t understand something, and they think the onus is on you. They believe that if it makes sense in their heads, it should make sense in yours.

The problem is that what works inside your gray matter doesn’t always work on the page. For example, say you’re writing about a movie that jumps back and forth between Present Day and the Old West. As the writer, you’ve been prepping this dual-time story forever. So by the time you start, everything about it makes complete sense to you. Your first scene, then, follows a detective walking into a murder scene. After the scene is over, you cut to a whorehouse in the Old West. Now to you, this cut makes perfect sense. To a reader being introduced to the story for the first time, however, it’s confusing as hell. How did we get from a murder scene to a 19th century brothel??? The solution to orientating the reader is quite simple. Just insert a title card that says “1878 – The Old West.” Now the cut reads as structured and intentional, as opposed to random and bizarre. It seems quite obvious but beginner writers often don’t know to do this.

And that’s the problem. If a script contains as little as three or four confusing moments in the first act, the script is shot. It gets too confusing for the reader to follow along. I mean sure, we have a vague sense of what’s going on, but the particulars are hazy, and the particulars are what make a script a script. Now the more I started thinking about this problem, the more I realized there weren’t any articles out there specifically addressing it. Which seemed strange to me because it’s an issue that comes up three or four scripts a week in my reading. Hence, why I decided to write today’s post. I want to give writers the tools to BE CLEAR in their writing. So here are some guidelines to follow that should keep your screenplay easy to understand.

A CLEAR GOAL – One of the simplest ways to write a clear story is to set up a big goal for your main character in the first act. In Trouble With The Curve, we establish that Eastwood’s character must correctly scout a minor-league player or lose his job. In yesterday’s script, The Almighty, I was never clear on what the ultimate goal was. Stop Lucifer maybe? But we had to get through a lot of gobbledy-gook to get to that point, and even then, I wasn’t sure if that was the ultimate goal. So, as a beginner, instead of having a bunch of changing or shifting goals during your story, keep it simple. Your hero should be going after one thing (Indiana Jones goes after the Ark). Following this one rule is going to take care of most of your clarity problems.

GET RID OF UNIMPORTANT SUBPLOTS – Lots of writers will add subplots that feel completely separate from the main storyline. So instead of enjoying them, readers spend the majority of the time trying to figure out what they’re doing there in the first place. This detracts from the primary story (the main goal), making the story difficult to follow. Subplots are good. Just make sure they’re plot related.

GET RID OF UNIMPORTANT CHARACTERS – I can’t tell you how many times I stop reading a script to ask the question, “Who is this person???” Characters that have only a minimal effect on the story should be ditched or combined with other characters. The more characters there are in a script, the harder it is for the reader to keep track of everyone, and the more confused they get. They’ll start mixing people up, forgetting who’s aligned with who, and just outright forget characters. This is a big reason for reader confusion.

REMINDERS – Depending on how complicated your story is, you may need to remind your reader every once in awhile what the goal is. Even if your story isn’t complicated, you’d be surprised at how quickly a reader can lose track of why we’re on this journey. In The Hangover, Bradley Cooper’s character is constantly reminding us that they need to find Doug. For simple stories, you may only need to remind the audience twice. For complex ones, you may need to remind them as many as six times. Feel out the complexity of your story and determine the number from there. But a good reminder of what we’re doing and why is always helpful to the reader.

STAY AWAY FROM FLASHBACKS, FLASHFORWARDS AND DREAM SEQUENCES – In the hands of beginners, these devices are script suicide. I’m not even sure what it is, but when new writers attempt them, they almost always occur at random times and result in total confusion. I just read a script two weeks ago that started with a woman getting married. The very next scene had that same girl walking into a pharmacy and flirting with a different guy. Questions: Why was our protagonist going to a pharmacy right after her wedding? And why was she trying to pick up a guy hours after getting married? Eventually I figured out that this was a flashback. But how was I supposed to know??? This kind of thing happens ALL THE TIME, even with more advanced writers. So the best solution is to just keep your story in the present. Use these devices if they’re necessary for telling your story (Eternal Sunshine Of The Spotless Mind). But make sure that they’re properly notated and that there really is no other way to do it.

KEEP YOUR WRITING SIMPLE – I was just discussing this with a writer the other day. He’d written this huge lumbering opus and peppered every paragraph with 20 adjectives and 90% more description than was needed. Even when I did manage to understand what was being said, it felt like I’d run a marathon through quicksand. After awhile, it became so laborious to read through even the most basic scenes, that my mind tired out, and it became difficult to follow what was going on. Therefore, it wasn’t that the information wasn’t on the page. It was that we had to dig through a pile of words to get there. Do that too many times and the reader gives up. And when that happens, your script becomes unclear by reason of exhaustion.

MAKE SURE EACH SCENE HAS A CLEAR GOAL – Believe it or not, there are tons of writers out there who can’t even write a clear scene. ONE CLEAR SCENE. And it’s usually because they don’t have a gameplan. They just sort of write what comes to mind. So make sure going into a scene that you’re doing four things. First, make sure you have a goal for the scene. For example, you want your two leads to meet. Second, make sure the scene moves the story forward. In other words, the scene should be required to get your protagonist (either directly or indirectly) closer to his ultimate goal. By “indirectly” I mean, yes, Indiana Jones wants the Ark, but the scene where he goes to Marion is required because she has a piece of the puzzle required to find the Ark. If she doesn’t have that piece, this scene isn’t moving the story forward, and therefore isn’t needed. Third and fourth, make sure both characters in the scene have a goal. So in the Marion Intro scene, Indiana’s goal is to get that puzzle piece, and Marion’s goal is to keep it from him. This basic setup should ensure that every scene you write makes sense.

IF YOU DON’T TELL US, WE WON’T KNOW – In your mind, Indiana might be standing right next to Marion, but if you don’t tell us, how are we supposed to know? In your mind, the bar might be full of people. But if you don’t tell us, we might assume it’s empty. In your mind, the bad guys are in the room adjacent to our hero, ready to strike. But if you don’t convey that, we may assume they’re in a room all the way across town. Writers leaving out basic information is one of the quickest ways to scene confusion. For example, I just read a script where two friends were sharing secrets about a guy named “Joe.” But Joe was right there in the room next to them! I was so confused. How could they secretly be talking about a guy who was right there??? The writer later explained that Joe was actually on the other side of the room, so he couldn’t hear them. Well how the hell was I supposed to know that? Again, it’s a matter of assumption with a lot of beginners. They assume things are obvious. But the reality is, if they don’t tell the reader, how the heck is the reader supposed to know?

Now in the end, sound storytelling principles have the biggest effect on clarity: A strong goal. A hero we want to root for. An interesting story with exciting developments. Escalating stakes. If you do that, you’ll keep the reader’s interest. If you don’t, the reader will get bored and start checking out, missing things because they’re just not into your story anymore, and hence start getting confused. And one last thing. When you’re finished, give your script to a friend to read and just ask them if it all makes sense. Drill them on parts of it. Ask them questions. Make sure it’s all clear. Then, and only then, should you unleash your screenplay into the world.