Search Results for: F word

Congratulations!

You’ve finished your script. Now what???

Before I answer that question, let’s talk about productivity, since that was a common theme that came up throughout this challenge.

At one point or another, everyone battled with putting words on the page.

From what I could tell, these issues fell into two categories.

Category one was writer’s block. You could open the script but you didn’t have any ideas for what to write.

Category two was resistance. You couldn’t muster the motivation to even open the document up and write.

Of the two, writer’s block is more manageable because it’s a temporary bump in the road. You’ve reached a point in the screenplay you don’t have ideas for and because it’s harder to come up with a solution than it is to give up for the day, you often chose to give up.

This is why it’s helpful to have a page count per day. It’s a psychological hack. If you know that you have to hit a certain page count, you won’t care that you don’t have the solution. You’ll push through. But if your only criteria for writing is that you have the perfect answers, chances are you won’t write anything.

I get that some people don’t like to write this way. They’d rather write nothing than write something bad. But in the grand scope of screenwriting, it’s a lot easier to work with something than it is with nothing. So write in that imperfect scene or sequence knowing that, with some distance, you’ll be able to come back later and make it better.

The second issue – resistance – is a much bigger problem that can be broken down into its own two categories.

The first is you’re not connecting with this particular script idea on an emotional level. There’s nothing you feel passionate about in the story, whether it be thematic or the characters themselves. One of the reasons Jordan Peele was able to keep working on Get Out for nearly a decade was because he had something to say about race. If his story was just about bringing home a boyfriend to some weird parents, he never finishes that script.

Or the recent spec sale, “Shut In,” about a recovering meth addict trying to save her children from an abusive husband. I’m guessing the writer, Melanie Toast, had an intense emotional connection with that main character. She may not have been a drug addict herself but maybe she’d been in an abusive relationship before and having her heroine overcome that issue helped her find closure with that abuse from her own past.

You’re more likely to get up and write every morning when you’re connected that deeply with your material. So get in there and create some characters that you have an emotional connection to!

The second is that you have some deep blockage when it comes to writing. Maybe it’s a pursuit of perfectionism. Maybe you don’t believe that you’re good enough. Maybe you experienced some screenwriting trauma whereby you wrote something you were proud of and everyone who read it didn’t like it. Maybe you’ve beat your head on the door so many times without getting in that you think, “What’s the point anymore?”

It’s hard to sit down and write anything when you’ve got that going on in your head.

But it should comfort you to know that every artist goes through this on some level. You’re not alone. In fact, I was just watching a video the other day from a successful guy in a separate craft who I considered one of the most confident people I’d come across. And, out of nowhere, he conceded that he still struggles with a basic belief in himself. That was shocking to hear because I never would’ve guessed that with him.

The difference is he didn’t allow it to cripple him. He felt it but he didn’t let it win. Which leads me to a couple of solutions for you.

One, look into the self-critic. Writers are particularly susceptible to the self-critic because they’re in their minds all the time. This breeds a nice warm nest for the self-critic to operate in.

Eckhart Tolle is the most respected voice in silencing our inner critic but there are newer books out there which offer new tools to take the self-critic on. I can tell you from my own experience that learning how the self-critic operates has helped me become a mentally stronger individual. You’d be amazed at how much more productive you can be when you’re not spending 75% of your mental energy each day beating away the guy in your head who tells you you suck.

Finally, you may need to reevaluate how you approach writing. If you’re approaching writing in a manner by which you’ll only be happy once you become rich and successful, you are not going to become rich and successful. In addition to handicapping you mentally, artists don’t create their best stuff when their only motivation is success. They achieve their best stuff when they have something to say.

So instead of trying to write something amazing that brings you tons of money and success, write to have fun. Write for yourself. That’s the whole reason you started writing to begin with, right? Well let’s get back to that. Once that becomes your definition of happiness, everything else is gravy.

Okay, getting back on track here.

You’ve just finished your script. Now what?

Some people will tell you to leave it alone for two weeks. Let it sit there. Get some distance from it. That way you can read it objectively and see what you’ve got. I’m not sure that applies here. We’ve written this so fast that I’m not sure we know what we wrote. So if you’re not burned out, read the thing right now! See what you’ve got!

If you see potential in the story, start a new document and write down ideas for the second draft. Usually, in first drafts, we’re coming up with all these new ideas in the second half of the screenplay. A second draft is about moving some of these ideas up into the first half. For example, if you unexpectedly realized that a secondary character is a lot more interesting than you thought they were, give them a bigger storyline in the first half of the screenplay.

One of the less heralded screenplay lessons I’ve learned is the importance of identifying which characters are working and which aren’t. Don’t get locked in to who gets the most screen time just because that’s how you originally conceived them. If one of your characters is killing it, give us more of them! Likewise, if someone isn’t working, throw them out.

From there, you’re just trying to identify the 2-3 biggest issues in the script and come up with solutions for those. For example, if your main character is boring, ask yourself, “How can I make her less boring?” It might be adding a sense of humor. It might be giving her a more controversial backstory. It might be making her more active.

You’re not trying to build Rome in the second draft. You’re just trying to build upon the potential of your first draft.

I’m really happy for everyone who participated in this and wrote an entire screenplay through this exercise! You now have a great base for a screenplay that, with some intense rewriting, you’ll have ready to go by the time the Last Great Screenwriting Contest deadline rolls around.

I’ll be taking tomorrow off but I will see everyone on Tuesday with a script review. :)

Okay, it’s time for me to be… how to I put this nicely?

Parental.

I still love you but I have to teach you a couple of lessons.

I’ve noticed a good chunk of excuse-making in the comments section about why writers aren’t keeping up.

One of the biggest reasons is: Not enough time.

My response to that?

B.S.

And I can hear your resistance already. The anger is bubbling. You can’t wait to get down in that comments section and explain to me why YOUR situation is DIFFERENT from everyone else’s and how you actually truly seriously don’t have enough time to get your pages written.

B.S.

B.S. with a capital B and a capital S.

The only way you don’t have enough time to finish your pages is if there is an anti-screenwriting terrorist in your home pointing a gun at your head all 24 hours of the day and telling you that if you write anything, he’ll shoot you.

Unless that is going on, you have time.

If you are operating by the 2-Week screenwriting principle of not judging your writing, you can write 8 pages in 2 to 3 hours.

If you’re still convinced that you don’t have enough time, post every hour of your day and what you were doing during that hour in the comments section. I’m certain that the intelligent Scriptshadow community can help you rearrange some things to find two hours to write.

And if your excuse is that, sure, you do have the time, but you’re stuck and you don’t know what to write next – KEEP WRITING ANYWAY. I don’t care if you write a redundant scene or a scene that feels pointless. As long as you keep writing! Because when you write, you’re more likely to come up with ideas, and when you come up with ideas, you’ll have reason to keep writing.

“But… but… but… but…”

No buts. You know it’s true. You have time to write. Now stop making excuses and just do it.

On to something I’ve noticed a few of you having trouble with – dialogue.

Here’s the dirty little secret about dialogue.

Are you ready?

DON’T WORRY ABOUT DIALOGUE.

That’s it.

That’s the only thing you have to know about dialogue at this moment.

Why? Because there’s never been a script where more than 10% of the dialogue from the first draft made it into the final movie.

Dialogue is the most re-shaped component of a script and that’s because a) it’s easy to rewrite, and b) the more you learn about your characters over the course of a project, the better you understand what they’d say and how they’d say it. Not to mention plots are constantly evolving in rewrites, which means a lot of scenes are getting chopped, which means all those hours you spent obsessively slaving over that dialogue turned out to be for nothing cause the scenes no longer exist.

How insignificant is dialogue in the grand scheme of things? Remember how we talked about the Safdie Brothers writing 160 drafts of Uncut Gems?

Even WITH THOSE 160 drafts, they still did scripted takes AND “say whatever you want” takes with their actors. In other words, they knew that dialogue, while important, isn’t as important as your actors believing in and emotionally connecting with what they say. So after ten years of rewriting a script to death, the finished product still consisted of a ton of dialogue literally made up on the spot.

Yes, everyone, I understand that the Safdie Brothers are writer-directors and don’t need their dialogue to shine on the page. But still: dialogue should be one of the last things in the script you perfect. Once you’ve got your structure down (which usually takes about 6-7 drafts) and you therefore know you won’t be cutting many more scenes, that’s when your focus is going to shift to dialogue.

In the meantime, there’s two types of dialogue you should be writing in your first draft. Functional or fun. Functional dialogue when you’ve got exposition to convey to the writer. And fun for everything else.

So if you have a scene like in Jurassic Park where the characters are explaining the rules of the dinosaurs or how the theme park works, just get that dialogue down. It doesn’t have to be entertaining. You’ll make it entertaining in future drafts. Right now, it doesn’t matter if it’s dryer than sand. You just need to get it down.

And if you have a scene where two characters with some sexual chemistry are on their way to the next big set piece, have fun with their dialogue. Be outrageous, witty, silly, clumsy. You’re not trying to hit a home run your first at-bat. You’re trying to get a general feel for who these people are and the things they might say. These scenes can be twice as long as they’ll end up being in the final draft because you’re in exploratory mode.

With that said, I know that writing a good dialogue scene makes you feel good. And when you feel good, you want to write more.

So here are a couple of tips. One, try to have at least one dialogue-friendly character in your script, someone who likes to talk, has a lot of opinions, is clever, is funny, or all of the above (think Tony Stark, Harley Quinn, Oscar Isaac’s character in Ex Machina). Just having that character around will up the quality of your dialogue 30% without you having to do anything.

From there, look to dramatize scenes. Create some element of conflict within the scene. That conflict will force your characters to interact with dialogue that’s more fun to listen to.

For example, here are two scenes. You tell me which one is more likely to result in good dialogue.

The objective of the scene is to set up a pandemic virus that’s emerging so that the audience understands it for plot reasons we’ll explore as the movie goes on.

In our first version of the scene, Joe tells Sara why the virus is so dangerous. Sara, eager to learn, asks a lot of questions. “Where did the virus start?” “How many people have died so far?” Joe answers all the questions and when he’s finished explaining everything, Sara thanks him.

We’ve achieved what we’ve set out to do. The audience now understands the virus at the center of the movie.

Now here’s a second version of the scene. In this version, Joe and Sara have two different mindsets about the virus. Joe gets a lot of his news from conspiracy websites. He’s up to date on the latest unfounded theories. Sara, meanwhile, only trusts official fact-based data that’s been reported through official channels. The two debate each other on what’s real and what isn’t.

Note how, dramatically, this is a much more interesting way to talk about the pandemic than a simple Q & A session. The main difference is that there’s conflict between the characters and whenever you have conflict, the scene is more charged, and when a scene is more charged, it’s generally better.

This isn’t the only way to write good dialogue, of course. But it’s an example of where your mindset should be to set a stage for the most interesting conversations. You want to create a situation that has some dramatic value and isn’t just characters saying what you need them to say to set up the plot.

But don’t get too wrapped up in that. You don’t need to focus on dialogue in the first draft. You need to write the darn script. So whatever you do, keep writing. And stop sabotaging yourself. You have the time. And as long as you don’t judge your writing, you will get your 8 pages. Trust me. You just have to sit down and do it.

It is time!!!

Today is the day we start writing our scripts.

For those of you just popping in, we’ve spent the last six days prepping for this moment. Here are those posts: Day 1. Day 2. Day 3. Day 4. Day 5. Day 6.

Now you’re probably wondering, “How are we going to write a script in just 2 weeks, Carson? I know you’ve had us prep everything and we even wrote a basic outline, but writing scripts is hard. You run into problems. You run out of ideas. You get writer’s block. There are so many ways a script can get derailed.”

All of these things are true.

IF!

Your standards for a first draft are too high.

We’re going to institute something called THE 2-WEEK SCREENPLAY PHILOSOPHY to ensure that you finish this script.

The 2-Week Screenplay Philosophy is simple: You will not judge what you write.

Sounds simple, right? But when you dig into it, it’s an extremely powerful mindset. The reason we often struggle to write is because we’ve set the bar too high. Many writers are cursed with the perfectionism gene. We want every scene to be great. When it isn’t, we get down on ourselves, spiraling into a belief that our idea is terrible and that the script doesn’t work.

That’s not going to cut it for the 2-Week Script. We have to be okay with subpar writing. Our goal is to GET OUR STORY DOWN ON THE PAGE. Then, later on, we can allow our analytical selves to identify the weaknesses in our script and come up with strategies to fix those weaknesses in rewrites.

But now, we can’t worry about that.

Let me be clear about this. If you are unhappy unless you write a great scene, you will not finish this exercise. It is imperative that you let go and allow the scenes to write themselves.

This does not mean don’t think about how you’re going to craft a scene. But you have to hit a certain number of pages a day. So if you get stuck not knowing what to do, write the most basic version of the scene and move on.

Speaking of pages, it’s time to get down to the nitty gritty. We have to make two decisions moving forward. How we package our daily goals and how we schedule our writing for each day.

Let’s begin with the packaging. You need to write either 4 scenes or 8 pages a day. After 14 days, that will bring us to 112 pages. Note that both of those numbers are the same thing. 4 scenes at an average of 2 pages per scene is 8 pages. Psychologically, however, they’re different. Since 4 is a lower number, it will seem easier to achieve for some. But if the number 8 doesn’t scare you, it’s fine to use that as your daily goal.

I understand that each script is unique and that each writer is unique. So not everybody is going to be writing 2 page scenes. In those cases, page count might be better for you. But if you ask me, I think 4 scenes is the easier measurement. Cause 4 scenes is easy. I can write a scene in 10 minutes. So can you. Not if you’re super-judgmental, you can’t. But if you let go, you can write scenes very quickly. I see no reason why you can’t write 4 scenes in two hours.

That brings me to our second component, scheduling our writing time.

One of the biggest reasons writing doesn’t get done is because writers don’t set specific times to write. They go off of “feel,” using the crutch of, “I’m an artist. I need to be inspired.” WE AIN’T GOING TO DO THAT HERE.

I am giving you three scheduling options to choose from.

OPTION 1: Write your 4 scenes or 8 pages in the morning. You can take a shower, eat breakfast, and have coffee. Spend 10 minutes checking up on the coronavirus news. But after that, you have to write.

OPTION 2: Write your 4 scenes or 8 pages at night. You’re living a little more dangerously here. But I’m aware that some of us are creatively dead in the morning and that the artistic juices don’t come alive until later. I’m fine with this as long as you pick a set time. DO NOT GO OFF OF “FEEL!”

OPTION 3: Split it in half. 2 scenes or 4 pages in the morning. Then 2 scenes or 4 pages at night. The reason I’m throwing this option in there is because anybody can write 4 pages. I mean, come on. It’s so easy. This is a screenplay. There’s 3 times as much white space as there are actual words. The “split” option is another psychological hack to help writing feel more manageable.

And that’s pretty much it. There’s no magic pill to this stuff. It’s about getting the pages down. My suggestion is to do the 4 scenes in the morning. That way, you get it out of the way and you feel good about yourself for the rest of the day. If you wait til the evening, you allow anxiety to seep in, you worry about running into problems you can’t solve and “What happens if I can’t think of anything and I don’t finish my four scenes?” Working in the morning gives you some room in case the unexpected happens.

As for how I’m going to structure the posts over these next two weeks, I’m not going to talk about general script issues every step of the way because every script is unique. Someone writing Avengers is going to have different problems than someone writing Get Out. So what I’m going to do is keep an eye on the comments section and see what you guys are struggling with. If I find consistent themes or things that resonate with me, I’ll post about them.

But mainly these next two weeks are about getting the pages written. And I know you can do it. Don’t judge yourselves. Writing is fun. Let whatever comes out, come out. You are going to surprise yourself. Now get writing!

You’ve been dreading it.

That word.

That evil enemy of all screenwriters.

The seven-letter word that may as well be the seven circles of Hell.

I’m talking about the…

Outline.

Look, I’m not going to debate you on whether it’s good to outline or not. For this script, you’re going to outline. And the good news is, it’s not going to be some elaborate ordeal. All you’re doing is taking everything that you’ve already written down and organizing it into a slightly more structured document.

A script is roughly 50 scenes. That’s assuming it’s 100 pages long with an average of 2 pages per scene. You might be writing longer scenes, like Quentin Tarantino does. That’s fine. You can easily calculate how many scenes you’ll write if your scenes average 5 pages per scene. 20 scenes.

The reason this is a nice number to know is that, now, when you lay out your outline, you can number the scenes and know how many scenes you’ve already imagined and how many you have left. Also, you’ll know where you’re missing scenes. You might have a bunch of scenes packed up in the first act and very few scenes after that. That should be an indication you need to add a few more scenes later on.

We want to make this outlining as simple as possible so here’s what I’d recommend doing. Divide it into four sections (First Act, Second Act A, Second Act B, Third Act). Each section will consist of 8-14 scenes depending on your writing style and the type of movie you’re writing. If you’re writing like Tarantino, closer to 8. If you’re writing like Michael Bay, closer to 14. Then, just start putting the scenes down chronologically and numbering them.

Since time is tight, all I care about is getting the bare essence down in the outline. But if you want to give yourself notes or write down some dialogue you had for the scene, by all means, go for it. You already have four scenes, since all of you did the checkpoints exercise. So put those in first. Then start filling in everything else.

By the way, I know that for some people, it’s confusing what constitutes a scene. If a couple is having an argument in their living room, then one of the characters storms upstairs, the other follows, and now they argue in the bedroom, does that constitute one scene or two? Generally speaking, if there’s a location change, it’s a new scene. But if the scenario naturally flows from one location to another, you can easily count it as one scene. Sometimes it’s up to the writer to decide. Kind of how it can be arbitrary where to break and start a new paragraph in a novel. I would constitute the above character argument as one scene. But if there was a small pause where both characters caught their breath in the middle, you could easily argue that it would be two scenes. The point is, don’t get too caught up in all that. What matters is we get as many scenes into the outline at possible.

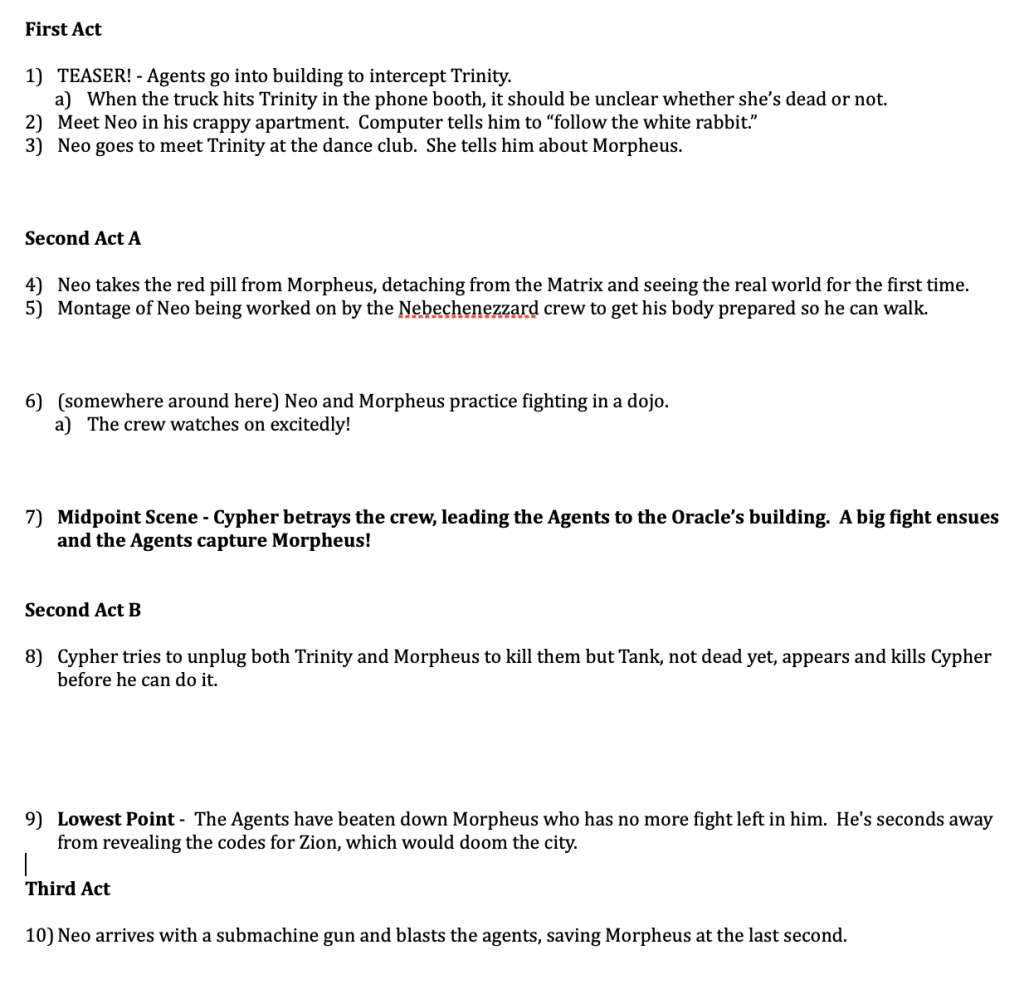

Here’s a general idea of what you should be going for…

As you can see, I’ve got 10 scenes figured out for a script I’m working on called “The Matrix.” Doing the math, that’s roughly 20-30 pages worth of scenes. Which gives me a good indication of how many more scenes/pages I need to get my full 100-110 page screenplay. Notice I’m leaving space between areas where I don’t know what’s going to happen yet. That’s so I have a visual indication of where I need to fill stuff in.

Just to be clear, don’t worry if you don’t have everything figured out yet. A big part of writing is discovering things along the way. So you’ll get new ideas as you’re writing Monday, Tuesday, and Wednesday, which will help you start filling in some of the thinner sections of your outline as you go. And, of course, if you don’t jive with this outlining method, feel free to use your own. Just remember that we’re all trying to do something different this time around to see if there’s a better approach than what we’ve been using in the past. So I encourage you to give this a shot.

Wow, six days later and we’re ready to start writing!

I’ll begin the official WRITE A SCREENPLAY IN 2 WEEKS posts Sunday night at 11pm Pacific time. That’s where I’ll tell you, specifically, how you’re going to approach this to easily finish a screenplay in two weeks.

Seeya then!

Today is Day 2 of Prep to write a screenplay in 2 weeks. You can read the announcement for the 2 Week Screenplay Challenge here.

We’re five days away from FADE IN and we’ve got a ton of work to do. By this time tomorrow, you need to know what script you’re writing.

Yesterday, I told you to prepare 5 loglines for scripts you want to write. Then, either e-mail five friends of yours and ask them to rank the ideas from best to worst. Or post the loglines right here in the comment section and have the Scriptshadow community rank them for you. Whatever gets the most votes, I’d suggest you write that idea.

If you want my personal opinion, my logline service is still cheap. $25 for a rating, a 150 word analysis, and a logline rewrite. I will reintroduce the 5 loglines for $75 deal through the weekend. E-mail me at carsonreeves1@gmail.com if you’re interested.

Like I said yesterday, committing to an idea will be the most important decision you make in this challenge by far. Good ideas inspire exciting stories. Weak ideas are like swimming with cinder blocks tied to your feet. Every scene is a chore. Finding the next plot beat is akin to finding toilet paper at the supermarket.

How do we define a good idea versus a bad one? While it may seem like how good an idea is is in the eye of the beholder, there are things you can do to improve an idea’s potency. A good idea is one that does a lot of the writing for you. Common factors include a strong main character goal, a heavy dose of conflict in the way of your hero’s journey, and the stakes feel big. That’s important – that this story feel like major consequences are involved. If you want to add even more charge to the idea, contain the time frame. Create a sense of urgency (the goal must be achieved soon or else…).

I would also like to introduce a new concept that has a major effect on how appealing your idea is to others. It’s called CREATIVE POTENTIAL and you want your ideas to have it. Sure, you can put a John Wick like character in your lead role and say he has to kill the evil bad guy within 28 hours or his family will be executed. That hits all the beats I mentioned above. But with zero creativity behind the setup, it doesn’t leave a lot of openings to give the story anything people haven’t seen before. Nor does it offer opportunities for surprising plot revelations. It’s a bland straightforward idea that lacks anything to distinguish it from the pack.

So what’s a good idea that contains all these things?

Jurassic Park, duh. I know it’s an oldie, but it’s a goodie. A group of people gets stuck on an island of dinosaurs. Goal = escape. Stakes = their lives. Urgency = they’re being chased so they have to achieve the goal NOW. Conflict = dinosaurs are trying to kill them. Creative Potential = a freaking island of dinosaurs. There are so many fun creative plot things you can do with this setup.

Okay, what about a bad idea? An idea that doesn’t “write itself.”

I’m going to say Marriage Story. I know I just used that as an example yesterday of an easy script to write but now I’m having second thoughts. The idea doesn’t have a goal. It doesn’t have any stakes really. The damage to this couple is already done at the start of the story. The narrative is used to get us to the legal finish line of the divorce. There’s clearly no urgency here. The script’s sole dramatic engine is the conflict between the central characters, which admittedly works well. But because you don’t have any real goal pushing the narrative, coming up with scene ideas for this must have been a nightmare. It’s always easy to see how they got there in the rear-view mirror, but I suspect there were a lot of long nights of Noah Baumbach staring at the blank page not knowing what to write next. Goal-less characters are responsible for driving many a writer insane.

And here’s another good idea…

This one a longtime Scriptshadow reader alerted me to from a previous contest – “It’s Christmas time in Berlin, 1944. A serial murderer is on the loose, and a confounded police detective springs a famed Jewish psychologist from Auschwitz to help him profile and catch the killer.” – The script would go on to sell to Fox. We’ve got our goal – catch the killer. We’ve got stakes – people are dying. We’ve got urgency – the longer it takes to catch him, the more people die. We’ve got some great conflict at the center of the story – A German police officer and a Jewish psychologist working together during one of the most tense times in history. And the creative potential of this idea is off the charts. You know you have a good idea when anybody who reads it can start thinking up fun scenes to write.

Finally, here’s one of Magga’s loglines from yesterday, which I had issues with. I hope Magga is okay with me critiquing it because your other idea, Shalloween, sounds great.

LIVE FOREVER – At the height of the britpop craze, demand for the Oasis live experience was so high that several cover bands got national reputations in England. This is the story of a fictional one.

Where is the goal in this idea? I suppose it’s for this fictional cover band to perform live? Okay. I guess that’s not terrible. But if I have to dig to understand the goal, then I don’t know what the stakes are. I can’t find the urgency. I’m not seeing any conflict in this logline, which gives me no sense of what the second act is going to be about. It also feels weird that the first half of this idea is about a real time and real people and the second half introduces a fictional element. Who cares if some fictional Oasis cover band gets to play live? This would be so so so much better if this was a true story.

But look, don’t feel bad if your idea isn’t loved. Picking ideas is an inexact science. The reasons we fall in love with an idea don’t always match up with how the rest of the world perceives them. Our hero may remind us of a fresh take on our favorite movie character of all time, “John Smith” from the movie “Takedown.” Meanwhile, everybody else just sees a generic straight-to-video action thriller. This logic can be applied to Live Forever. Magga may love Oasis and that’s why they’re passionate about writing a movie about them. But all we see is a confused story with a weak narrative.

That’s why I want you to share five movie ideas instead of one. At the very least, you’ll be working with an idea that beat out four others. So, if you want to participate, post your five movie ideas below in the comment sections. Please include titles and genres.

You must pick a movie idea by tomorrow because tomorrow we have to start prepping to write the script. We only have five days for prep. So let’s get to it!