Search Results for: F word

What’s that old saying?

Turn lemons into lemonade?

Well by gosh, that’s what we’re going to do here at Scriptshadow.

We’re indoors for the next few weeks. Let’s make the best of it.

I know a lot of you are hard at work on your Last Great Screenplay Contest entries. So feel free to follow this journey for fun. But for the rest of you, we’re going to write a screenplay…

IN TWO WEEKS!

I know, I know. Sounds impossible, right?

Don’t worry. I’m going to guide you through every step. I’ll be here for the good and the bad, the highs and the lows. Trust me, it won’t be as hard as you think.

And just to be clear – I know that nobody’s going to write the next Citizen Kane in two weeks. But what you can do is write a first draft that contains the bones for a great screenplay. We’ve heard tons of successful writers tell this exact story. Jon Favreau wrote the first draft of Swingers in a few days. Sylvester Stallone wrote the first draft of Rocky in what? A week?

And with me by your side, I’m going to make sure you don’t make any of the classic mistakes writers make when writing quickly.

Now the actual writing doesn’t start until Monday. But we’re going to get started right now.

“Whoa, Carson. Give me time to… like… breathe. You’re throwing a lot at me here.”

Good. This process is going to feel a little uncomfortable and that’s a good thing. The only way this is going to work is if you push yourself outside of your comfort zone.

We need to come up with a concept.

Maybe you already have an idea you’ve been sitting on for a while, itching to write. Maybe it’s an offbeat concept that’s always scared you a little bit. This is the perfect opportunity to bust that idea out and write it because what’s the downside if it’s bad? You lost two weeks. No biggie.

But for those of you hoping to write something specifically marketable, you’re going to come up with five loglines for potential screenplays… BY TOMORROW.

“But… but Carson… writing… takes… time. Come up with five ideas in one day?? That’s impossible!!!”

Stop.

Just stop.

One of the primary directives of this experiment is to eliminate negative thinking. Eliminate doubt. Doubt slows you down. We don’t have time for it. We have to write a script in two weeks.

You’re going to come up with five loglines and then, tomorrow, you’re going to e-mail five of your friends OR five people on Scriptshadow OR post your loglines in the comments section and you’re going to get a consensus on which is the best idea. That’s the idea you’re going to write.

One of the BIGGEST mistakes screenwriters make is starting with a weak idea. It’s hard for even the best screenwriters to make a weak concept work. You want to give yourself the best chance to succeed. This, more than any other decision you make, is going to have the biggest impact on whether your script is good or not.

A word of advice. Don’t pick ideas that have too much mythology, require too much research, or have too many characters or storylines. While it’s possible to write one of those scripts in two weeks, they tend to take longer than that.

So any fantasy concepts like Lord of The Rings – throw them out. The Big Short, a script that would require extensive research about the 90s stock market – throw it out. The Godfather, Gladiator, World War Z, Avengers. These will be tough scripts to write in two weeks.

Simple concepts with low character counts will be the easiest to write. Rocky. Get Out. A Quiet Place. Ladybird. Parasite. Marriage Story. Joker. Swingers.

I don’t want to stifle creativity so if you have an idea that doesn’t fit this mould and it still appeals to you, by all means, write it. Just be aware that the more characters there are to track, the more time it will take to work out the plotting. And the more complex your plot, the more likely it is you’re going to run into walls. Walls are where screenplays become tough. You hit a thick one you don’t have answers for and that can keep you away from the computer for days. We’re only going to finish a script in two weeks if we’re writing EVERY SINGLE DAY so keep that in mind.

One of the themes you’re going to hear me hit again and again these two weeks is LACK OF JUDGEMENT. Judgement is the main reason for writer’s block. For those of you who struggle with that, these two weeks are going to be a revelation. Because it’s not about writing something great. It’s about writing something period. And then, when it’s over, we can look back at what we’ve written and decide if it has potential to keep working on. If it doesn’t, that’s okay. We only lost two weeks. And we didn’t even lose much because we were going to be home with nothing to do anyway.

So that’s all you have to worry about today. Either pick some idea you’ve been sitting on for a while or come up with five loglines. Tomorrow’s comment section will be dedicated to sharing your loglines so that fellow writers can give you feedback on which one is best. However, if you want to get a head start, feel free to post your loglines in this comment section. I only ask that you post all five of your loglines in a single comment. Don’t keep gumming up the comments section every time you come up with a new idea. “Is this good?” 30 minutes later. “What about this one??” Let’s avoid that.

Another theme you’re going to hear me hitting over and over again is: Let’s have fun. A lot of times we get bogged down in the frustrations that come with writing. We’re throwing that to the wayside here. We originally got into writing because we enjoyed it. And these next two weeks, we’re going to get back to that mindset. Let’s have some fun and write a script! It’s not going to be any more complicated than that.

I already know some of you are itching to leave a comment about how this is bad for screenwriting. Nothing good is ever written in two weeks. You’re going to come up with reasons why you’re different and why you can’t do this. That’s fine. I will give you one day, here in this comment section, to get those thoughts out. Cause I get it. Writers are often pessimistic creatures. But after today, those comments won’t be allowed. I will delete them.

Moving forward, it’s going to be about staying positive so that we can get a screenplay written. It’s going to be a blast. I can’t wait to see what you come up with. :)

Genre: TV Pilot – Drama/Sci-Fi

Premise: When a young genius Russian programmer is accepted into a tech company’s top secret program, codenamed “Devs,” he ends up getting more than he bargained for.

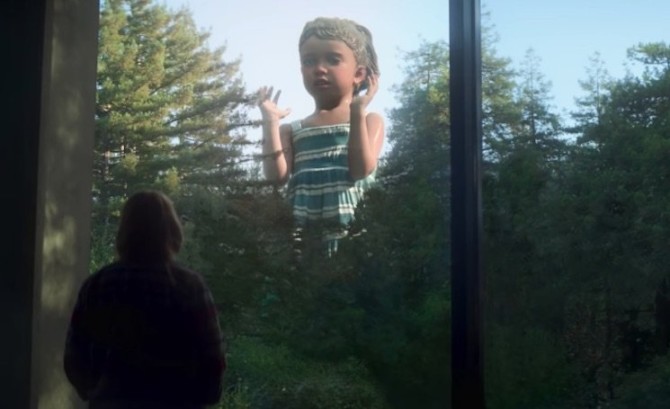

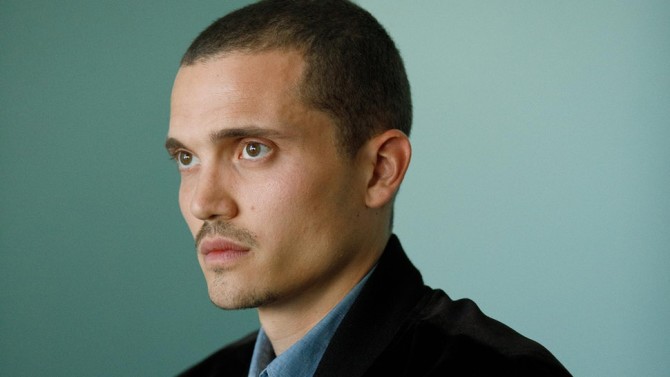

About: It’s so like Alex Garland to put his show on Hulu. I mean, who puts any show on Hulu?? They produce 3 shows a year and all of them blow. Garland is one of my favorite writers. He wrote the novel, The Beach, which still holds up today. He wrote and directed Ex Machina. He made the trippy sci-fi flick, Annihilation. He wrote 28 Days Later. Sunshine. Like a lot of creators, Garland is finally making the jump to television with his new show, Devs.

Writer: Alex Garland

Details: 1 hour

One of my favorite quotes came from Alex Garland when he was on the interview circuit for his first directing effort, Ex Machina. The journalist asked him, “You’ve been a writer for so long and here you’ve finally gotten behind the camera. I’d imagine it’s an invigorating change, being able to take your words and translate them to the images you had in you head. What is it you like about directing?” Garland’s response: “Nothing.”

I don’t know if Garland isn’t aware of how the promotional game works or if he just doesn’t care. Either way, I’ll follow him because, the way I see it, Garland is one of the top 5 writers in the business. He has an intrinsic understanding of what a hook is. But he never explores them in obvious ways. He’s like a non-smiling JJ Abrams. Literally. There is a GIANT LITERAL MYSTERY BOX in the show – the Devs building, a building that’s about to change the life of the man who’s been accepted into its program.

(SPOILERS)

Sergei works for a San Francisco tech company led by Forest, a reclusive tech CEO. After Sergei demonstrates to Forest that he is able to predict the movements of a single-celled organism seven seconds into the future, Forest informs Sergie he wants him to join Devs, his mysterious passion project.

Sergei and his girlfriend, Lily, are besides themselves. It’s impossible to get into Devs. That night, Forest takes Sergei to the Devs building, a giant oddly-shaped box in the middle of the forest surrounded by large gold pillars being used as shields to ensure that nothing can be digitally transmitted out of the building.

The inside is even more impressive, with an electromagnetic floating people mover that takes you to the inner offices of the building. There, Sergei is given his computer station and when he looks at the Devs code, he stares up at Forest in shock. “This can’t be real,” he says. Forest assures him that it is.

After Forest leaves, Sergei starts acting strange. He seems to be having an internal breakdown. Finally, we see him position his watch to face the screen. Sergei is digitally recording the code! Late that night, when Sergei leaves the building, he finds Forest waiting for him with his head of security, Kenton. After Forest tells Sergei he knows exactly what he did, it’s lights out for Serge. Kenton throws a bag over his head and suffocates him.

The next day, Lily, who also works at the company, comes looking for her boyfriend. She meets with Kenton, who tells her they’re lucky they have so many cameras all over the place as it will be easy to find out where he went. Sure enough, the cameras show Sergei leaving Devs, coming to the main campus, then simply heading off into the city. Kenton assures Lily that he’ll pop up sooner or later.

Later, Lily finds a strange game on Sergei’s phone. When she clicks it, it becomes clear it’s not a game at all, but rather a covert messaging system. Sergei, it turns out, was working for the Russians. Before Lily can process that, she’s called in to see Kenton again, who shows her a disturbing video. It’s Sergei. He came back, headed straight to one of the on-campus parks, then poured gasoline on himself and lit himself on fire. Lily can only watch with horror as her boyfriend commits suicide.

Garland is a writer who understands screenwriting. Period. He just gets it, man.

I want to draw your attention to two scenes in particular.

The first occurs after Forest’s head of security, Kenton, kills Sergei. The next day Lily comes to Kenton’s office asking if he knows anything about Sergei’s disappearance. Now we watched Kenton kill Sergei. But Lily doesn’t know that, of course. Garland has prepped the perfect scenario for dramatic irony.

As a reminder, dramatic irony is when we know something that a key character, many times the hero, does not. We know this dude killed Sergei but Lily does not, creating an underlying sense of anger and frustration that our hero, this person we care about, is being lied to. Any time you can get the reader feeling emotion – good or bad – you are doing something right. Because the main source of boredom is having zero emotional reaction to what you’re reading.

But Garland doesn’t stop there. He DOUBLES DOWN on the dramatic irony. During their conversation, Forest comes into the office. Kenton “informs” Forest that Sergei, Lily’s boyfriend, went missing after he left Devs last night. Forest feigns concern and asks what happened. Forest and Kenton then go through a little performance whereby they pretend to figure out where he might be. It’s like taking dramatic irony and hooking it up directly to a nuclear reactor.

For all you TV writers out there, dramatic irony is one of the most important skills you’ll draw upon. The reason for this is that there are lots more talking heads scenes in TV shows than features and dramatic irony is one of the easiest ways to make a talking heads scene interesting.

The next scene I want to draw your attention to is the scene where Sergei is killed. Sergei has just finished his shift in the Devs building, using much of that time to record the code via his secret watch-recorder. Sergei exits the building, which is in the middle of a forest, and is surprised when Forest emerges from the shadows (yes, Forest emerges from the forest).

Now Forest already knows he’s going to kill Sergei (or have Kenton kill him). When he reveals to Sergei that he knows Sergei recorded the code on his watch, it’s pretty much a done deal that Sergei’s going to die.

But where’s the fun in killing off a character the second we learn they’re going to be killed? Screenwriting is about suspending. You want to imply that something bad is going to happen and then you want to draw it out. The fun occurs in the audience squirming around during the ‘drawing out’ process. Which is exactly what happens here. Forest goes on an extensive monologue about how human lives are on rails and that they’re pre-determined to do what they do. Only after finishing his point does he order Kenton to kill Sergei.

But I’m not done documenting Garland’s genius. Garland uses a scene in the second episode to establish a pattern-disruption which ensures that audiences have no idea what to expect moving forward. That’s not talked about enough in dramatic TV writing. Most shows are predictable. The way you hook people is by taking major plot beats and mixing up the pattern of expectation. Sometimes you give them what they expect. Other times you don’t. This ensures that they never know what’s coming, which is key in one’s enjoyment of any story.

(spoiler) In episode 2, Kenton confronts Sergei’s Russian contact, Anton, in a parking garage at night. Kenton informs Anton that he knows he’s trying to get Lily to complete Sergei’s job and he wants him to stop. But unlike Sergei, Anton is not afraid of Kenton, and as the two continue their tense interaction, it’s clear that Anton has done his homework and knows everything about Kenton. By the end of their conversation, you’d think Anton even knew Kenton had followed him here. Then, in a flash, Anton whips out a knife and stabs Kenton in the gut. Shocked, all Kenton can do is flail. In that moment, we know that Kenton is going to die.

Sticking with the mantra that drawing big moments out is one of the keys to good writing, Garland milks the fight for all it is worth. As it teeters back and forth, Kenton surprisingly fights his way back to even ground. Anton is younger and stronger, but Kenton won’t go down easily. When it’s all said and done, Kenton surprisingly emerges as the winner, a bet we wouldn’t have taken at the beginning of the fight.

Why am I telling you all this? Because now Garland has established that you DO NOT KNOW what’s going to happen going forward. Sure, we knew Sergei was a goner. But with this fight, the winner wasn’t who we thought it would be. This means that every tense moment moving forward in the show, you’re going to be anxious. You’re going to be unsure. It can go either way. And that’s what makes any story exciting – the unknown. The main reason why there’s so much boring stuff out there is the predictability of the storytelling. You don’t get that here.

Notice none of what I’ve discussed even includes one of the coolest things about this show – the Devs project! What is it? What is it going to be used for? Is it just a camera into the past? Or can it do the same for the future? Is the goal to be able to travel into other time periods? Another mistake TV writers make is that they only focus on this plot stuff. But the cool plot stuff becomes a lot cooler when you have cool characters moving within it. That’s why this show is so great.

TV feels like the perfect landing spot for Garland. This guy explores complex themes. Complex people. Complex ideas. Film doesn’t do any of that well. Film is more about the ride. Even character pieces can only focus on one or two aspects of character growth in a film. TV allows you to take all those things and dig into them. And whereas many feature writers moving into TV give us shows that burn bright early but die after a few episodes, Garland is ready for this drawn out format. Remember that he started off writing novels. So he understands long-form storytelling better than most.

My only worry with Garland is that his stuff is a little TOO heady at times. Whereas JJ Abrams could learn a thing or two from Garland about sophistication in theme and character development, Garland could learn a thing or two from Abrams about embracing the fun parts of your idea more. The good news is, this show is on Hulu and Hulu has nothing going on so you’d think they’d greenlight a second season just based on that. You have a cool hip cinephile-loved director making a show for you. Keep him happy.

I know I was happy watching this. So much so, I can’t wait for the rest of the season.

[ ] What the hell did I just watch?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the stream

[x] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: One of the most misunderstood aspects of screenwriting is when to write monologues. There are two assumed places where one must do so. The first is when a character explains some deep affecting story from their past that shaped them. These monologues tend to start like this: “When I was a kid, my dad used to say…”. The second occurs near the end of the movie where the main character says to either the co-lead or a group of people what they learned and try to encapsulate the message of the movie in one big speech. While the latter is preferable to the former, I’d advise avoiding both. They’re cliche-traps that scream “Newbie writer here!” The best time to use monologues is in the example I used above. Create a sense of impending doom then draw the scene out. Whatever you want to say, have the controlling character (in this case, Forest) deliver it in a monologue during that moment. The issue with monologues is that they are inherently inorganic. People rarely stop and give some grand sweeping speech about something. The impending sense of doom hides that inorganic component better so you don’t notice it as much.

Genre: Thriller/Period

Premise: After finding themselves stranded on the wreckage of a Helldiver bomber in the middle of the ocean, an American aviator and a Japanese Kamikaze pilot must work together to survive their greatest threat yet — a 22-foot great white shark.

About: This script finished with 9 votes on last year’s Black List. Like a lot of writers on last year’s agency-absent Black List, this is writer Ben Imperato’s breakthrough screenplay.

Writer: Ben Imperato

Details: 91 pages

If you’re anything like me, you’re still reeling from the beating Barb put on Madison last night. If you don’t know what I’m talking about, that would be because you have a life. If you do know what I’m talking about, OMG CAN YOU BELIEVE THAT HAPPENED? I thought the whole family was going to break up by the end of the night. I think we can all agree that the real winner was Hannah Anne.

Anyway.

World War 2? Sharks? Hero and Antagonist working together? Sounds like the perfect spec script to me. Let’s find out if it’s any good.

Edward Moretti’s plane spirals out of the sky and into the Pacific, landing upside-down. He and his gunner, David, are barely able to get out of the cockpit without drowning. But within minutes of their miraculous survival, David realizes he was shot during the air battle. He dies within minutes, leaving Edward all alone.

Not to worry because Edward has his good friend, Flashbacks, to keep him company. We cut back to right before the war where Edward and his perfect pregnant wife talk about how great their future is going to be.

Four days into this nightmare, Edward receives another guest, Hiro, a 17 year old Kamikaze pilot who happens to be the one who shot them down. Unfortunately, he got hit during the battle and ditched his plane as well. Furious that Hiro killed his friend, Edward battles Hiro, who takes him on with his katana sword. The fight ends in a stalemate and the two draw a line along the bottom of the plane and make a rule that each person has to stay on their half of the line.

Just after things calm down, a giant angry shark begins circling the plane. At one point, it’s able to grab onto Edward’s leg and tear half of it off. Feeling bad for Edward, Hiro starts to work with him, trading some water he has for a fish Edward caught. We flash back to Hiro’s past as well and learn that he was kinda conned into sacrificing his life to help the Emperor win the war.

After a few more battles with the shark, three Americans in two rafts pick Edward and Hiro up. These men have long since gone crazy. And if you needed proof, they’re carrying along with them the head of a Japanese soldier they killed. When they try and go after Hiro’s head as well, Hiro fights back and Edward helps him defeat his own men! The two head back to the plane, and after a couple of final flashbacks, take on the shark in a climactic battle.

This is a good idea for a movie.

I like whenever two people on opposing sides have to work together. And like I always tell Scriptshadow readers: If in doubt, add a shark.

But a setup is just that. It sets the concept up. From there, it’s up to you to execute.

I want to highlight an early line in the script because it was a telling moment for what was to come.

David, the gunner who’s been shot, is dying in Edward’s arms. This is what he begins to say: “Hey Eddy… My wife. My kids. Tell them…”

When these moments come up early in a script, my ears go up like antennas. Because it’s a common scenario. The soldier who’s dying in another soldier’s arms and wants the other soldier to tell his wife/girlfriend/family/kids one last thing. It’s here where I learn whether this writer understands how to give me something new or whether he’s going to repeat the same lines that we’ve always heard.

So how does David’s line end? Here’s the full exchange: “Hey Eddy… My wife. My kids. Tell them… Tell them I tried to get back.” “Tell them yourself.”

Sound familiar? Yes. It’s the same exchange we always hear in these interactions. And when I read that, a small part of my script-reading self died. Because I know from experience that if a writer can’t even give me a fresh take on a line, then how are they capable of giving me a fresh unexpected story experience?

How SHOULD you handle a line like this? First off, I would avoid writing the exchange in the first place. If there’s a moment in your script that’s so cliche that comedy films have made fun of it, that’s a good indication you should avoid writing that moment. Didn’t they have an entire scene making fun of this in Tropic Thunder?

Anyway, moving on.

The flashbacks confirmed to me that this wasn’t going in any direction that was going to be entertaining. Flashbacks are always a sign in movies like this that the writer can’t think of enough story to fill up the present so they pad it with flashbacks.

That’s not to say flashbacks couldn’t have worked. If each character’s past would’ve been engaging and unique and shocking, I would’ve been all for them. But both Edward and Hiro’s flashbacks were as straightforward as you get. Blah blah blah wife has a miscarriage. Blah blah blah, Hiro’s too young to join the Navy but does anyway. It’s clearly padding.

What this script probably needed was to focus on this relationship on the plane. That’s your concept. That’s what brought people to see the movie. So the more time we’re spending with these two facing problems and troubleshooting them together, the better.

The best moment in the script happens when the crazy American officers arrive because it was the only time in the script that went off the obvious narrative path. If you were making a short film from this movie, that’s the sequence you would build the short around.

With that being said, I can still see this getting made. I can still imagine the trailer. I can see people watching the trailer and getting excited over the movie. But this needs an A-List screenwriter who knows what he’s doing to put in a full-on rewrite to bring out the parts of this story that make it such a fun idea.

I will say one thing. Years ago, there weren’t a lot of places that could make a movie like this. It would’ve been a mid-budget 40-50 million dollar deal because you’re shooting on water. And water is both unpredictable and expensive. If you shot on a real body of water, it’s a logistical nightmare and you’re constantly at odds with the weather. If you shot in a tank, you’d have to fake the backgrounds and that never looks realistic in the daytime.

However, with this new Stagecraft technology you can probably shoot a movie like this for 3-5 million dollars. The reason that’s important to note is because when you write a screenplay, your odds of selling it are directly linked to how cheap it would be to make. The cheaper your script is to make, the more production houses there are you can sell to. Go study how Stagecraft works because it’s opening up opportunities to make movies that used to be pipe dreams. Certain conditions have to be met (A central still location like a floating plane is perfect for Stagecraft) but as long as they are, there are huge opportunities for indie filmmakers that were not there 10 years ago.

Helldiver wasn’t a bad script. The execution was just bland and predictable. The idea needed to be pushed and it was only nudged.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: “I love you.” Another cliched line we’ve heard a million times in movies. So how do you make it work? Also, how do you make the response work? Shall we take a trip down Star Wars memory lane to find out? When Princess Leia says, “I love you,” the original response from Han Solo was written as “I love you too.” They tried to shoot it. It didn’t work. So they tried rewriting the line. Didn’t work. Rewrote it again. Didn’t work. Take after take after take, new lines written, same reaction. Didn’t work. Finally, Director Irvin Kershner told Harrison Ford to say whatever. Ford, exhausted by this point and wanting to go home, hears “I love you” and replies, “I know.” The line becomes one of the most famous film lines of all time. But it would’ve been boring and cliche had the line been delivered as originally scripted. How they came about “I know” is the same way you should go about your writing during common moments. Whatever you come up with first is probably going to be lame. Whatever you come up with second is probably going to be almost as lame. It’s only when you keep digging deeper and deeper that the response becomes something totally unexpected, maybe even nonsensical, and yet it will be a million times more original than your first pass. That was my issue with the “Tell my family I tried to get back,” “Tell them yourself,” exchange. It is the epitome of a first pass. Seasoned writers don’t make that mistake.

Hey guys, Carson here! Today I’m posting a story from a long-time Scriptshadow reader who went through a harrowing experience to say the least. Those of you who frequent the comment section already know his story. But for those who don’t, get ready. Because this is going to make your blood boil. I did not think there were people like this out there. Here is the latest update on… the Con Queen of Hollywood.

Some of you probably know me already. I’ve been a regular here at Scriptshadow since before it had the dot net. That might have even been before Carson had his very first In-N- Out burger. That’s like the stone age! I’ve also had my fair share of AOWs over the years, so I’ve taken my beatings, and fought the good fight. I can say beyond a shadow of a doubt, that it’s because of Carson, and the incredible community of brilliant commentators he’s nurtured over the years, that I am the writer I am today. I’d also like to thank Carson for the opportunity to write this post. This is coming full circle for me, and it’s very, very surreal.

Those of you who are active or lurk in the comments might be familiar with some of this story, but in recent months there have been some major developments that I promise will blow your mind if you haven’t been keeping up.

In July, 2015, my friend Dave and I wrote a script called “Shadows Below,” and made it onto AOW. But I was young. Naive. A mere level 3 writer on Carson’s writer-scale as indicated by this post.

So when I lost the AOW, I threw down the gauntlet! My submarine script had to be better than that damn music biopic! It just had to be! So Carson, saint that he is, reviewed it anyway… and it wasn’t worth the read.

I was devastated. I was so sure the script was great, and it wasn’t. What was I doing wrong!? But before I knew what to do with it, I got a response from one of my queries, Jing Huilang, a film development executive at a website I’d found: thechinafilmgroup.com (Don’t worry, the site’s defunct now).

After submitting answers to lengthy essay questions, she requested a copy of the script, including a forty page mood board, a synopsis, and a strategy pitch. Everything seemed professional. Legit. And before I knew it, Dave and I were on an airplane on the way to Jakarta, Indonesia, to take a meeting with a panel of producers from the company.

There was just one catch.

We had to book our own airfare, and pay for the expensive driving service employed by the company. In cash. But not to fear! They were going to reimburse us. Suffice to say…

We were about to get conned.

Only one man showed up for our meeting. He went by the name of Anand Sippy, and he was a vice president. The blowoff was masterful. The script wouldn’t get past the Chinese censorship board. Have a nice flight back to New York! That’s exactly how it went for everyone else he lured there. A quick flight in, a quick flight out, and he’d pocket the driving fees. Thing is, he always found his own targets, but this time was different. I had reached out to him. Like a fish that jumped onto his boat. It was the perfect scam. But when he told us the project was dead, I pivoted. Wait! What if it was a sci-fi, I pitched! In a fantasy world, where the politics weren’t real. Then we could get past the board! In retrospect, as I offered him the chance to turn his short con into a long one, the look he gave me was downright diabolical.

Dave and I spent months going back and forth to Indonesia, all with the singular purpose of developing the treatment for Shadows Beyond, a fantasy based on our original screenplay. Every step of our journey was dictated by a detailed daily schedule, one which we had to adhere to religiously. Our pace was grueling. Days and nights packed with work on little sleep. We took long trips all over the country, studying local myths and legends, while meticulously documenting every location with pictures and notes.

It was awesome. It all seemed like the legitimate procedures of a professional film studio. There was a lot of paperwork! All with official CFGC seals and stamps. Nearly a dozen different employees in their own e-mail chains, and each of them diligently keeping track of every aspect of the process. It fooled everybody.

And it was all orchestrated by Huilang, the female voice over the phone. The maestro. She made our schedule, and she checked on us at every opportunity. Calls every morning. Texts while we were out. Nightly development sessions. Her honey-sweet dragon-lady voice is forever engrained in my memory.

She spent hours every day talking with my mom, my dad, and my sisters. She embedded herself into my family, and used them to manipulate me, making false promises of my bright future with the company, while dangling the ever looming threat of our project getting canceled should we make even the slightest misstep. It was a work of genius…

And it ended my friendship with my best friend.

After Anand got the treatment approved, before we’d set up a trip to China to write the script, we were to have one last meeting with him in Jakarta to sign the deal memo.

So when we were both in the hotel lobby, ready to leave, and they changed the plan to have Dave go ahead and meet with him separately before they’d meet with me, it came as a surprise.

I remember it vividly. Staring out the window, listening on my phone to the Mets play the Royals in the World Series as Dave drove away. I don’t remember what day it was, but I remember the Mets lost.

Hours later, when it was finally my turn, I was driven to a fancy office building. My fifth time there. At least. And this wasn’t a run-down shanty where some shady Indonesian con artist was grifting tourists. I might have mistaken it for an attorney’s office on Lexington avenue, if not for the armed soldiers standing guard outside. A secretary escorted me past security up to the fourth floor, where I was greeted by Dave’s bright grin as he exited Anand’s office. It was going well! Green light, baby! Our movie was going to get made.

So imagine my shock, when after an uncharacteristic motivational speech from Anand about how I could do anything, highlighted by his history as a poor street sweeper from India who’d overcome adversity, he told me that the deal was canceled, effective immediately. I couldn’t even go back to the hotel. It would be a violation of their company’s security protocols since I no longer worked for them. The driver had already gone to the hotel to collect our luggage, and we were to be taken straight to the airport, never to return…

And never to be reimbursed.

But why, I protested! I was furious. Confused. It didn’t make any sense! “Dave will tell you on the way to the airport,” he told me. “Goodbye.” I looked to my friend for answers, and he was smiling, as if to reassure me all would be well.

In the car he confirmed that unspoken look. It was my sister’s fault! But not to worry! We can fix it! At Huilang’s behest, my brilliant sister, who at the time was a vice president for a major financial institution in Manhattan, was attached as our manager. She had been corresponding with Huilang on a daily basis for months, but somehow that relationship soured, and unless we legally cut her from the project, the deal was off! Oh, no!

I was heartbroken. But fine. If that’s what they wanted, then that’s what they’d get. We always did everything they asked of us. Failure was not an option. It was at the airport, waiting for our flight due to depart in sixteen hours, when the house of cards came crashing down. I called my sister, prepared to break the bad news, when she floored me with news of her own.

It wasn’t my sister they wanted out, it was Dave. They didn’t want him to write the script. They thought he’d cause problems. They even claimed he said horrible things about me and my family in his meeting. What a contradiction! Who was I to believe? I knew in my heart that my best friend would never lie to me. But my sister had it in writing. She even forwarded me the e-mails. Dave was resting peacefully on a bench, arms and legs wrapped around our luggage. He was no Judas.

On the surface it seemed a paradox, but in that moment, I saw it for what it truly was. There was only one explanation.

I was being conned. And this was the blowoff.

The subsequent fallout of the next few months was more devastating than the [x] Wasn’t for me. I was wounded. So was my family. Emotionally. Financially. Dave never spoke to me again. My mom felt humiliated. How could she, a Brooklynite with street smarts, fall for a con artist!?

But I wasn’t left with nothing. I had the treatment. And fueled by both the inspirations of the supportive scriptshadow community, and the occasional mockery, I persevered, and the treatment transformed into a script. A high budget, four-quadrant fantasy, that would be nigh but impossible for an unproduced writer to sell. It felt good to finish it. It was special. A gem that ought never have existed, if not for the glory of the con. And once it was done, I moved on to the next script, and the next.

Over the years, people always told me I should write a movie about my experience. I was in the perfect position. I’d reached out to numerous people who were also conned, and was even involved in group private investigations to track the perpetrators down and bring them to justice. But it wasn’t movie material, I protested. What was so cinematic about a couple writers touring Indonesia while writing. It lacked that x-factor, and I had fancier projects on my mind, determined to put it all behind me.

Until this article dropped in the Hollywood Reporter.

The Con Queen of Hollywood. Hundreds of people conned over the years. Major players in Hollywood impersonated by a mysterious woman over the phone. Big names. And it was all the same scam. She was collecting a fortune in drivers fees. Wow! It was finally hitting the headlines. I immediately called Scott, the article’s author, and started a dialogue with him to discuss my story, and everything I’d managed to learn.

It wasn’t until the following year that the bottom dropped out, when Scott published this article on the Con Queen.

That’s right! It was all one person. But not only that. It was a man! Huilang’s voice, the one that was in my ear, all day, every day, for months, was a man the whole time. But not just any man. Anand Sippy. The vice president we’d met with time and time again. He played every part. All the paperwork. The accountants. The higher ups at the company who were quick to keep us in check with harshly worded emails. The woman who’d turned my family and friend against each other, who’d acted as a creative mentor through a lengthy development process. The woman masquerading as legends like Kathleen Kennedy and Amy Pascal. It was him. All him. He was the mastermind behind it all.

I immediately got on a call with my friend Raza, who I’d co- written a bunch of scripts with, and we both had the same thought at the same time: now this is a movie.

Everything was happening at once. This bombshell information coincided with me being contacted by Jigsaw Productions, Academy Award winning Alex Gibney’s company, who were working on a podcast about the Con Queen and wanted to interview me.

What I found out, surprised me. I was one of the first people who got conned by this guy. Only a few other writers fell victim to the scam in 2015, and since mine was the only long con, I met him, in person, more than anyone else. Mine also had me traveling all over the country, so it meant he made the most money off of me. After I got conned, his scam changed. China Film Group was no more. He moved on from writers, and turned his sights on social media influencers. Photographers. Actors. All done over the phone. As a woman. Never in his real voice. Never with an in-person meeting. All with a new plot in mind. One born from my experience.

He had them go on tours. Via the trusty driver, he made out like a bandit. My determination to turn a no into a yes, had changed the game for everyone.

During this whole process, Raza and I wrote the script and decided to center it around the Con Queen himself. Making it a biopic on him. What drew him to lead this life? Why impersonate these powerful women? Being a victim of his nefarious schemes, and the one who interacted with him the most, I felt confident in telling his story and breaking down his character as I wrote. It was certainly cathartic in a way, but most importantly, it’s an engaging script about a man facing a complete crisis of identity, lashing out his worst instincts on those who would fall into his web of lies.

But there is a softer side to him. One that I saw in that final meeting with Anand Sippy. A rags to riches story. A hard worker. A man whose criminal genius one can almost admire.

Although getting conned like this was obviously a rough patch in my screenwriting career, I can only hope that this recent string of publicity can lead to some sort of justice. If not through the retribution of the law, then through the redemption of art.

Verifiable entertainment entities can request a copy of the script by contacting me: gregorymandarano@aol.com

Also, this Monday, March 9th, Jigsaw is releasing the first two episodes of a podcast series entitled, “Lies We Tell.” One of which is about the Con Queen, and features my interview. If you’re interested at all in this story please give it a listen and support the great work they do over there at Jigsaw.

“Lies We Tell,” can be found on the Luminary app.

I finally finally FINALLY got to see Uncut Gems this weekend and, Holy Moses, it did not disappoint. This would have been my number one movie in 2019 had I seen it in the theaters.

After watching the film, I do what I always do when I see something good, which is watch a thousand Youtube videos about the making of the film. And one such video caught my interest because it stated something I’d never heard before.

Until this moment, the script I’d heard had the most rewrites was Good Will Hunting. Nobody kept track. But rumors push it somewhere between 60-100 drafts. Well, it turns out Uncut Gems puts that number to shame. The Safdie Brothers, who directed the film, wrote 160 drafts of the script over a ten year period.

Now before you feel guilty about having submitted your script to The Last Great Screenwriting Contest with only three drafts, it’s important that we distinguish why some of these Uncut Gems rewrites were made.

When you’re directors or you’re a screenwriter working with a team of people trying to get a movie made, you’re constantly sending the script out to talent and every time you do that, it’s advantageous for you to cater the script to the actor you’re sending it to.

The Safdie Brothers point out that they went through numerous NBA stars to try and find the professional basketball player character in their movie. Since they’re Jewish and Howard (the main character) was Jewish, they had Amare Stoudemire as the original character since he is Jewish himself.

But then they heard that Kobe Bryant was looking to do some acting. Kobe is a completely different person than Amare. Not to mention, he existed in another stratosphere of stardom. Naturally, they had to rewrite the character to reflect this difference.

In the end, Kobe decided that he didn’t want to act. He was more interested in directing. So that casting choice fell by the wayside. Now imagine going through that over and over again. Anybody who’s tried to get a movie made understands this hell.

At this stage in the game, though, as an amateur writer trying to get noticed, you don’t have to worry about these kinds of rewrites. But then how many rewrites should you be writing?

I realize this is a gray area. A draft to one person may be quick and dirty while a draft to someone else might be a full-on teardown. One writer may even vacillate between those two kinds of rewrites, depending on what stage the script is in. There are also specific types of “passes.” You can do a dialogue pass where you go in there, read all the dialogue, and try and spruce it up. You might do a character pass where you focus on a specific character in a rewrite and try to make everything about him/her pop more.

But let’s say we’re averaging all of these together – both the long arduous structural rewrites and the quick and dirty dialogue polishes. I’d say that you need at least ten drafts to bring out the best in a script. And it’s probably closer to 20.

But there’s good news. There are things that can knock this number down. For every three screenplays you’ve written, knock one draft off your total number of drafts per screenplay. That’s due to you knowing more and getting more right early on. Knock two drafts off if you do extensive outlines. And one draft off if you do character bios.

The cause for the longest rewrites usually come from structural problems and the writer not having a good feel for the main characters. You can alleviate some of that if you do the work beforehand.

However, there’s a truth about screenwriting that not a lot of people like to talk about that tends to stretch your workload into the 15-25 draft territory. And that’s that the original concept you went into the script with will often change.

At some point, you’re going to realize that there’s a better version of your story. And in order to get to that version, you need to do a page 1 rewrite. It’s one of the worst parts of writing a script. Cause you think that the last five drafts of writing the script were now pointless.

And the sad part is that a lot of times, we’ll hold on to that original idea simply because we don’t want to face reality. But it’s not as bad as you think. Your story is radically changing, yes. You’re starting over, yes. But because of those previous drafts, you know this world WAAAAY better than you did when you first started. So the new version of your script will be more populated with a lot more specificity.

It’s funny because that very topic comes up in the 160 Draft Safdie Brothers video I watched. Josh Safdie talks about how he used to lie as a kid and he learned that the more specific he could make the lie, the more details he could add, the more believable the lie would be. Cause people would think, “There’s no way that could be untrue. There’s just too much detail.” So he incorporated that approach into their movies. The more detail you add, the more we’re going to believe this story is really happening.

But getting back on topic, if there’s no way you can imagine writing 15-20 drafts of a script, you have to adjust your approach even more. For example, you will need a super detailed outline. You will need to pick a subject matter that you’re familiar with. For example, with Jason Gruich who wrote Cop Cam, he *IS* a cop. If he wasn’t a cop, people are going to be pointing out all the errors in procedure and how police precincts don’t work that way. Those things require more drafts to fix.

You’ll also want to pick simpler stories. John Wick is going to be an easier script to write than Mission Impossible. Why? Cause there are less moving parts. That’s where screenwriting gets tough – when you’re managing multiple storylines, when you’re managing multiple character threads. But the real time wasted is having all those plot and character threads come together in an invisible way.

I suspect one of the reasons Uncut Gems took so many drafts to write was it’s a very dense plot (even though the movie is good at hiding it). Howard loans out the “uncut gem” to Kevin Garnett, who leaves his championship ring for collateral. Howard then pawns that ring in order place a bet on a basketball game. He needs the uncut gem back from Garnett the next day in order to enter it into the auction where he hopes to cash it in for a million bucks. Howard has a wife who’s pushing for divorce. He’s got a mistress who he can’t decide if he wants to run away with. And he also has outstanding debts with three different bookies around town, not to mention a side business of employing a dude to bring rich athletes to his jewelry store. I don’t care who you are. You do not figure that out all in one draft.

And I think that’s the way you have to look at it. Yeah, draft-writing is mainly problem-solving. You’re fixing plot developments that don’t work. You’re adding texture and depth to your weaker characters. You’re juicing up your final act with a better location. But draft-writing is also the primary process for discovering new ideas. Every time you write a new draft, you get new and better ideas that you can put into the script. The more you do that, the better the script gets.

And believe me, I can tell. I can tell when a writer hasn’t put a lot of work into a script. Yesterday’s script was a clear four-draft script to me. It’s that point where the writer understands what his movie needs to be but he hasn’t been with the script long enough to integrate all the changes needed to execute that vision.

With all this being said, if you’re 20+ drafts into your script, you have to start asking if you’re making the script better with each new draft. Sometimes writers write drafts that only make things different, not better. And that’s a dangerous pitfall to fall into.

How do you know when you’re finished? When there are no more drafts to write? That’s never an easy question to answer. For each writer, it’s different. For each SCRIPT it may be different. But for me it was when the time it’d take to write a draft was more laborious than the percentage of improvement a new draft would bring. And that was usually around 15 drafts. So I think that’s a good gauge to start asking if the script is good enough to keep rewriting. Cause sometimes it isn’t and you have to let a script go. But if something feels good and you have that feeling that it’s almost there, then by all means, keep writing those drafts.

I’ll throw the question to you guys. How many drafts do you write?

Carson does feature screenplay consultations, TV Pilot Consultations, and logline consultations. Logline consultations go for $25 a piece or $40 for unlimited tweaking. You get a 1-10 rating, a 200-word evaluation, and a rewrite of the logline. They’re extremely popular so if you haven’t tried one out yet, I encourage you to give it a shot. If you’re interested in any consultation package, e-mail Carsonreeves1@gmail.com with the subject line: CONSULTATION. Don’t start writing a script or sending a script out blind. Let Scriptshadow help you get it in shape first!