Search Results for: F word

This was a fun experiment. It took me back to the days when I read 8 scripts a day. When you’re looking at that much material within that short of an amount of time, it’s easier to identify what doesn’t work. And the biggest thing I discovered by reading so much material back to back is how generic most screenplays are. For example, I read 30+ opening scenes that dealt with cops arriving on a murder scene. 20+ opening scenes that dealt with a bank robbery. 15+ opening scene with characters starting their day. But it wasn’t just the generic nature of the setup. It was the generic nature of the execution. A bank robbery can be a compelling scene. But not if you follow the obvious beats (Get down on the floor. Give me your money. Run out and drive away). If anything, this exercise taught me that writers aren’t aware of just how much content they’re competing with and, therefore, how important it is to differentiate your work.

The next big issue I ran into was that a ton of these scripts started slow. Let me reiterate what this challenge was about. It was about hooking me from the VERY FIRST WORD and never letting go. I don’t know why anyone would think that a slow pan across a desert horizon was a good idea. Or the 40+ script openings that focused on how light was hitting something. Or plopping me down in a room with two characters chatting away. No doubt a sizable portion of these entries were writers sending their latest script in regardless of the exercise. But for those who understood the exercise and still started slow? Or even medium? Shame on you. You knew the rules. Hook me immediately. Not hook me on page 2 and a half.

Every once in awhile I felt bad because I wanted to give writers a fair shot. So I would read past the point where I got bored. But in every one of those cases, I was proven right. The script didn’t get better. It almost always got worse. And it’s frustrating because I feel like this is my fault. We talked about this for an entire month, with me going into detail about what works and what doesn’t and, still, writers are making basic mistakes. There were so many times where I would read the first half page, stop, stare at my computer, and wonder why anyone would think this would hook a reader.

To give you some stats. 80% of the scripts, I didn’t get past the first half-page. I’d say, of the 20% where I kept reading, 70% of those I didn’t get past the second page. The most common problems were…

1) The writer couldn’t construct a sentence.

2) The writing or the scenario was confusing.

3) The writer was more concerned with setting up characters than entertaining the reader.

4) The writer was more concerned with setting up their world (exposition) than entertaining the reader.

5) There was nothing original or unique about the writing or the situation.

6) The scene was straight up boring. Nothing was happening.

That last one bothered me the most because you’d think “Don’t be boring” would be obvious. And yet time after time we’d get these scenes that didn’t contain a single entertaining element within them. No drama, no conflict, no mystery, no comedy, no dramatic irony, no dialogue that popped off the page. I thought about this a lot and wondered why were writers violating something that was so obvious to me. I think the problem boils down to too many writers assuming you “owe them.” You owe them your focus. And when you’re writing with that mindset, you don’t care about keeping the reader’s attention. I can tell you right now, that’s a deadly mindset to have. If you want the reader to like your script, you HAVE TO GRAB THEM. And the only way to do that is to assume they’ll get bored unless you’re giving them your best.

If you could construct a sentence, if you could convey action clearly, if you started with a scene that could conceivably grab the reader, you made it past page 1. But now it’s a matter of, “Are you giving me anything new?” Anything new at all. It could be a reversal (that Silence of the Lambs example I used in a previous post where we’re led to believe the person being restrained is the victim, when in actuality, they turn out to be the bad guy). It could be a strong sense of detail that pulls me into the world. It could be pure talent, like Diablo Cody’s Juno dialogue. ANYTHING. If you did that, you got past page 2. But from here, you had to prove that you could construct a compelling scenario. For example, a writer might’ve opened on a shocking murder scene. Okay, you have my interest. But if the scene doesn’t build and contain conflict and move towards a satisfying conclusion, then I immediately lost interest.

If you could set up a compelling scenario, you got me to read the whole thing. And there were about 15 entries that got me to read all 10 pages. Four of those didn’t leave me with a good enough taste in my mouth to celebrate them here. The remaining eleven were all good. So here’s what I thought we’d do. I’m going to post the eleven winners here today and we’re going to do an impromptu 10 Page Amateur Offerings (which will last through the weekend). You guys will read the eleven entries and vote on your favorite. The winner will get a review next Friday. If the writer has a full script, I’ll review that. If they only have the ten pages, I’ll do an in-depth review on the pages, focusing on things we don’t get to normally explore when covering an entire screenplay. The winner will also get a feature consultation package from me! So really think about who you’re giving your vote to.

And I want to say one more thing to those of you who don’t find your pages here. It doesn’t mean you’re a bad writer. It doesn’t mean you failed. But you do need to redefine what grabbing a reader means. Because I know a lot of you are talented. And in almost every case with you talented writers, you wrote something better than average. But you didn’t write something that grabbed me. You didn’t write like your life depended on it, I guess you could say. If there’s anything I’ve learned from this, it’s that busy people whose lives revolve around reading and hearing ideas all day don’t have any patience. And you have to write with that in mind. Like I said when all of this started, write 10 pages that are impossible to put down.

Okay, here are our 11 finalists! Good luck to everyone! Oh, and these are my titles for the scripts, not the writers.

Entry 1: Late For A Flight

Reaction: Biggest “Oh s&*%” moment.

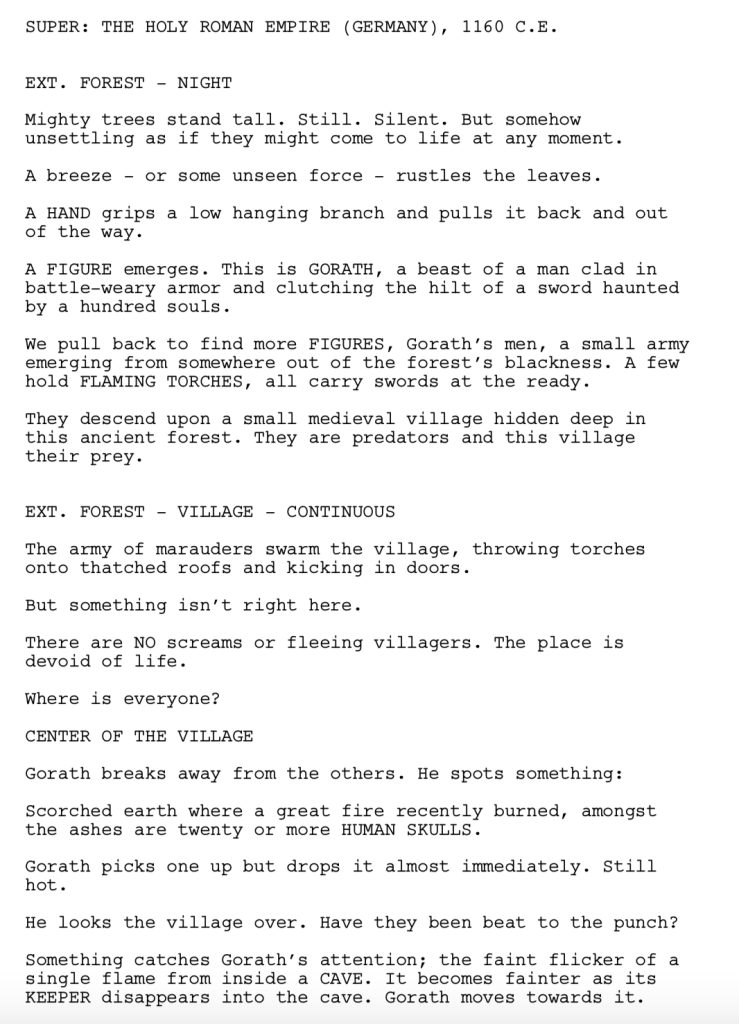

Entry 2: The Leper Cave

Reaction: Creepiest entry?

Entry 3: The Woman Who Disturbed the Rat

Reaction: Most talented writer in the bunch?

Entry 4: Cop Stop

Reaction: First entry that I read all ten pages of!

Entry 5: Waking Up in a Pool

Reaction: Top amnesia entry.

Entry 6: Confused Soldiers

Reaction: You knew time travel had to make it into a Carson contest somehow!

Entry 7: The Art of Pick-Pocketing

Reaction: Script I was most surprised I liked.

Entry 8: Pterodactyl Bliss

Reaction: Writer best suited for the current Godzilla franchise.

Entry 9: Roman Plagues

Reaction: Script that best took me back to a different time and place.

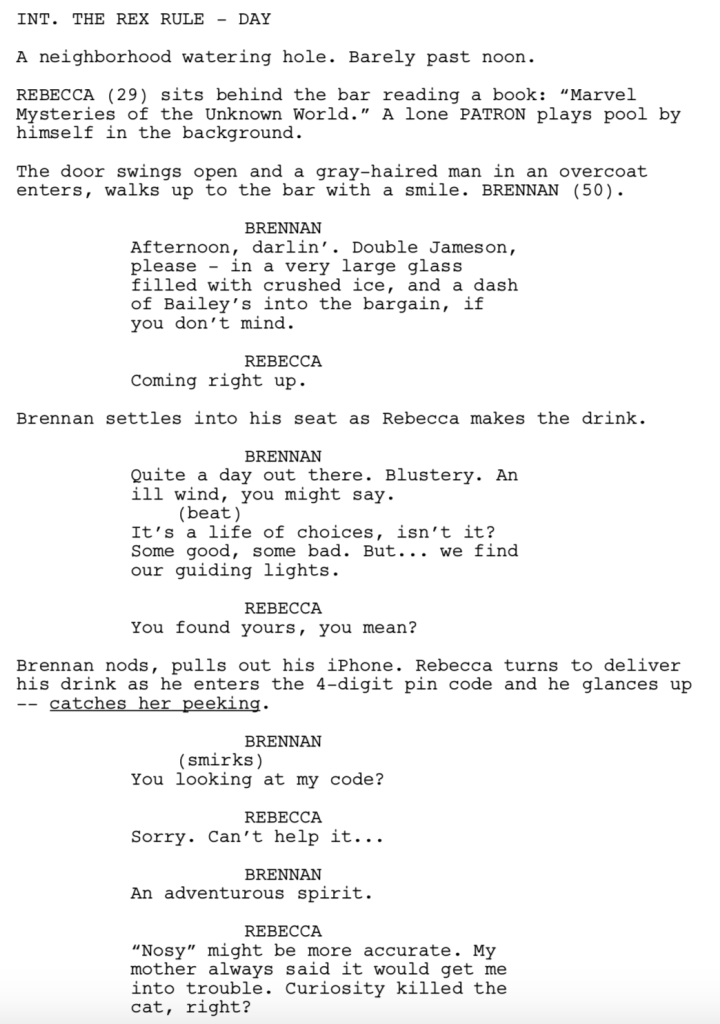

Entry 10: Don’t Take the Phone

Reaction: Fastest pages in the whole challenge.

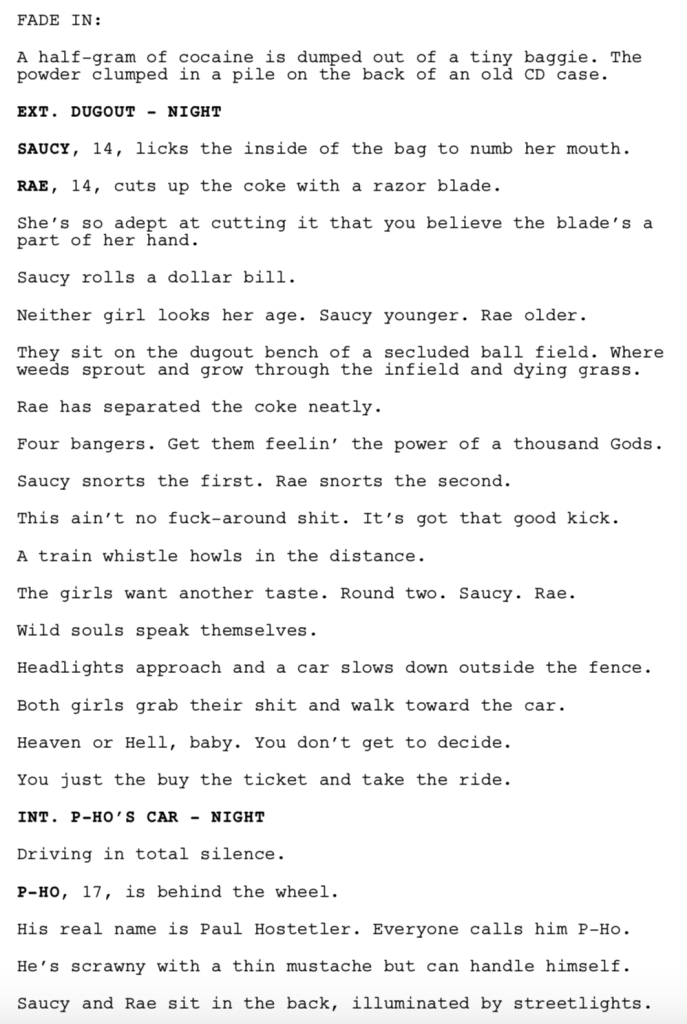

Entry 11: Cocaine Problems

Reaction: Darkest entry of the bunch.

I’ve been reading a lot of amateur scripts over the last few weeks and I continue to come across a troubling pattern. Boring scenes. I want to make something clear. You can be great with character. You can be great with dialogue. You can be great with structure. But if you don’t know what goes into writing an entertaining scene, none of that matters. After seeing this problem over and over again, I began to form a theory. I believe that one of the most well-known pieces of screenwriting advice – that you must move the story forward with every scene – has confused writers into believing that scenes are merely vehicles to get from point A to point B. Instead, you should be looking at scenes as their own individual movies. They must be entertaining in their own right. And as much as it can be done, they should have their own beginning, middle, and end.

The primary boring setup I encounter is the “talking heads in a room” scene. Whenever you have characters in a familiar generic room (living room, office, bedroom, kitchen, motel room) talking to one another, you should be worried. This is not an ideal setup for creating an entertaining scene. That doesn’t mean you can’t do it. Only that you are in danger of writing a boring scene. Why? Because you’re in a familiar setting and you’re depending on keeping the reader invested solely through your characters’ conversation. And if your storyline hasn’t pre-loaded this scene with drama, you’re stuck with two people droning on to each other.

Here’s the thing. These scenes are almost always the result of a faulty plot. If you’ve come up with a movie idea that doesn’t have momentum? That doesn’t force your character to go out into the world and do things? If your plot is passive or inert? Then chances are your characters are going to be sitting around in a lot of boring rooms talking to each other. And because there’s no engine driving your story, everybody’s going to be relaxed and talking about boring things. Let me ask you a question. How many familiar generic rooms was Indiana Jones in in Raiders of the Lost Ark? One? Two maybe? That’s because HE WAS TOO FREAKING BUSY TRYING TO FIND THE ARK OF THE COVENANT!

Don’t worry, don’t worry. I’m not saying you can only write entertaining scenes if you write action adventure movies. I’m just using that as example to explain that when you come up with a story that has a strong engine, that pushes your character to do things, there will be less instances where they’re sitting around.

Now the truth is, there will be scenes where your characters need to talk to each other in a boring room. In fact, there are some great scenes in cinema history that take place with two characters in a room. But not unless you know what you’re doing. And for that reason, I want to introduce a concept that will help you avoid this problem. It’s called SCENE TENSION. Whenever you write a scene, you want to ask where the tension is coming from. If there’s no tension, or the tension is weak, there’s a good chance you’re writing a boring scene.

Let me give you a basic example. A guy and a girl are discussing plans for the weekend. I wouldn’t want to write this scene regardless but let’s pretend, for whatever reason, that it’s necessary for the plot. If you were to write this scene in a living room with the two characters sitting down, it would be boring. To fix this, ask yourself where you can introduce some scene tension. What if the guy is late for a flight? He doesn’t have time to talk about this. He’s running around, feeling his pockets for his keys, checking his phone for his ticket. Meanwhile, this conversation is important to the girl and she’s trying to sort it out, but he can’t focus. This creates a natural conflict, which, in turn, makes the scene entertaining. I’m not saying this a great scene. But it’s magnitudes better than the first version.

Let’s look at another example. A mom is cooking breakfast for her children. I’ve read this scene hundreds of times. You can certainly write the scene so that the mom asks her kids how they’re doing. The kids ask for help on their homework. In other words, not a very interesting scene. However, if you look to add scene tension, maybe the mom just got a call in the previous scene from work, where it was revealed that they’re going to make layoffs today. Now the exact same scene involves an anxious mom who’s not paying attention to her kids cause she’s wondering if she’s going to get fired. Meanwhile, the kids are getting upset that their mom isn’t paying attention to them, and, as a result, the dialogue becomes more charged, more interesting.

Jerry Maguire is a master class in scene tension but look at the famous scene where Jerry Maguire comes to Dorthy’s house and tries to get her back. A writer could’ve very easily written a scene with Jerry and Dorothy alone in a room. But Cameron Crowe adds this divorce woman’s group – the worst possible people in the world to have around when you’re trying to get your wife back. The ultimate scene tension.

Or here’s one I saw the other day. A character was trying to have a conversation with someone else. But he kept getting important texts from someone, creating all sorts of tension in the scene. “Should we talk about this another time?” “No! No no no. I’m paying attention.” I’m not saying you always need a gimmick for a scene. Don’t let that be your takeaway from this article. I’m just using bigger examples to get my point across.

Actually, the most common way to add scene tension is through the characters themselves. You have a million options of who your character is in any moment. The most dangerous option you can go with is “fine.” If two characters in a scene are fine – if there is nothing bothering them, nothing eating at them, nothing pressuring them, nothing causing any level of unrest or anxiety, you are at risk of a scene heart attack. Actually, no. Heart attack implies it would be exciting. You are at risk of a scene coma. Which is why it’s critical you identify at least one character in the scene who’s exhibiting some level of unrest. That, then, will be the tension that keeps your scene entertaining.

I’ll give you a couple of examples. At work, a guy and a girl need to discuss relevant exposition that sets up important plot points later on. They go to the break room, maybe grab some chips from the vending machine, and chat away. Potential for a boring scene = high. IF, however, the guy has a secret crush on the girl, that “unrest” or “anxiety” adds tension to the scene. The exposition goes down a lot smoother because we’re focused on the subtext of the conversation.

And it can be even more subtle. Take Clarice’s first meeting with her boss, Jack Crawford, in Silence of the Lambs. That scene is a straight exposition scene, setting up Buffalo Bill, the serial killer. Now this isn’t the best example because a scene setting up a serial killer is kind of an interesting scenario. However, screenwriter Ted Tally still uses scene tension here. Clarice wants to impress her boss. She’s trying to prove that, even though she’s young and a woman, she’s worthy of this assignment. That “unrest” within Clarice creates the scene tension.

Let me now give you an example of a scene without scene tension. Guardians of the Galaxy 2. When Starlord meets Ego and Ego starts showing him around the planet, we get a very boring scene. The scene is exposition-driven but they forget to add any scene tension so the scene just drones on aimlessly as Ego explains tons of backstory and exposition to Starlord.

The reason writers screw this up so often is because they’re focused on getting the scene in their head down on the page, and as long as they’ve done that, they’re happy. For example, the plan might be to set up Character X in this scene. Or, like the Guardians example above, the plan might be to convey Relevant Exposition Y. They believe if they merely execute that plan, they’ve written a “successful” scene. And I can understand that. It is hard to write a scene where you get all the necessary exposition down in a way where it’s readable. But it’s only the beginning. You still have to entertain. Always. In every scene. Entertain. Never forget that.

And I want to finish off by reminding you that if you create plots with active heroes who go after things, you will encounter this problem way less. That’s because your hero is too busy to sit around in rooms chatting with people. He or she is out there trying to achieve their goal. But if you are writing a character piece, then you need to be an expert on scene tension. It’s gotta be in your writing DNA. Or else your script is DOA.

Genre: Thriller

Premise: (from Black List) When Grace and her husband Jay retreat to an empty vacation island to escape his grueling political campaign, Grace begins reliving traumatic experiences from her past, forcing her to question what is real.

About: Today’s writer came out of nowhere. Up to this point, he’d been writing and directing his own short films. But “Grace” got him onto last year’s Black List, where he finished 16th out of the 73 scripts. Marc Evans is producing the film over at Paramount.

Writer: Will Lowell

Details: 103 pages

I’m going to say something controversial.

If your script ends with your main character in an insane asylum, implying that the series of events we just watched were all in the hero’s head, you’ve probably written a bad screenplay.

Insane asylum endings aren’t much lower on the cliche ending totem poll than your hero waking up and realizing it was all a dream.

I say this as someone who has read in the neighborhood of 100 screenplays where the main character isn’t sure if they’re crazy or not and then, ultimately, ends up in an insane asylum.

While I don’t believe it’s impossible to write a “Am I Going Crazy” script, I’ve found that most of the writers who tackle them have done less than 10 minutes of research on what being “crazy” actually means. There are dozens of different variations of mental illness, all of which have unique side effects. There’s no such thing as blanket “crazy,” although you’d think so after reading a script like this.

It’s hard to trust myself to a writer who hasn’t done their due diligence in accurately portraying the driving force behind their entire story.

Grace Byrnes watches his Senator father hang himself from their summer mansion when she’s 9 years old. Right before he jumps, he smiles at her. After this happens, Paul Sheridan, her father’s political fixer, makes Grace swear that she’ll never tell anybody what happened here. They want to frame the father’s death as a heart attack. Sure, Grace says. She’s 9 so she does what she’s told.

Cut to 23 years later and Grace is the wife of Jay Connors, an all-star Democratic Governor who’s on the fast track for becoming the president of the United States.

Everything is going well in Grace and Jay’s marriage except for the fact that Grace has inexplicable feinting spells. It’s getting to the point where the media has picked up on it, and Jay is afraid it might affect his political aspirations. So he decides to take a week off and bring Grace to a place that feels like home so she can heal – her old summer house!

They show up at the house, which hasn’t been used in 23 years but is somehow still livable. And, almost immediately, Grace starts seeing things. Is that a man she saw behind a tree? Is that a man who walked behind her in the hallway? Is that a man in the upstairs window? Is that a man at the end of the bed? You could’ve just won the Fields Medal and not be able to keep up with how many times there’s a man just outside of Grace’s vision, who she then turns to, only for him to disappear.

Grace thinks she’s going crazy but refuses to check herself into a psychiatric ward because her mom rotted away in one. Eventually, Paul shows up at the house. Oh yeah, Paul is now Jay’s political fixer. One afternoon after they think Grace is asleep, Grace hears Paul and Jay discuss that this is all a setup to get Grace to agree to be admitted into the psyche ward so she’s not a liability on the campaign trail. Everything Grace has seen is a ruse! Now that Grace has uncovered Paul’s Scooby-Doo plan, she has to escape! But she’s going to have to outwit the craftiest political strategist on the East Coast to do so.

This was a bizarre read.

I get the feeling that this is a ten year old script that the writer dug up off of an ancient hard drive. The movie centers around a political figure yet there isn’t a single mention of the most influential tool in politics today – social media. There is never a tweet. Never a gram. Never a youtube video. So right from the start, something felt off.

What might have happened here – and I give the writer credit if it’s true – is that he determined the script could be marketed as part of the #metoo movement. If it takes 20,000 screenplay skill points to make the Black List, a #metoo angle gives you a free 10,000 points. So if the writer identified this and took advantage of it by digging up an old script, good on him. Screenwriting isn’t just about writing. It’s about market savvy. It’s about taking advantage of the system. He did that. So kudos.

But the script itself is too simple and too repetitive. And too repetitive. And too repetitive. After the 6,328th time that Grace saw a man out of the corner of her eye, I felt like I was the one going insane.

The ending is OKAY. And I say that because I thought Jay was going to be the killer. And it ended up being Paul. So I was surprised by that. But this is the most simplistic execution of an idea I’ve read all year. There’s nothing new or fresh here at all. And that sucks because I actually like these “couples out in the middle of nowhere one of them might be a killer” scripts. But this one didn’t do it for me.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: I find character descriptions fascinating. They’re a lot like loglines. Even if you’re good at screenwriting, you may be terrible at character descriptions. I think that’s because a) most screenwriters don’t read enough scripts to see how it’s done, and b) most screenwriters don’t make it a priority. But let me tell you why character descriptions are so important. One of the hardest things to do in screenwriting is write characters that leave an impact. And a character introduction is the starting point of that process. If it’s weak, it’s almost a guarantee the character himself will be weak. You want to start off on the right foot. Here are five character introductions from recent scripts I’ve reviewed (including today). Not all of them are good. I want you to see how impactful a good character intro is. And the best way to see that is to place it up against a bad one.

Dressed in paint-stained working clothes, caretaker BILL MCCABE (50s) has the unkempt appearance of a man who hasn’t had human contact in months.

ATTICUS ARCHER. 55. Silver hair. Oxford jacket. He methodically checks his watch, as he always does when a plan is unfolding. He has everything under control.

A curl of lights and camera crew surround a reporter, BINGBING (late 20s, the kind of woman who makes you think you’ve done something wrong with your life).

LIZ ROE, 40, sharp and self-possessed with an approachable beauty and ironic smile, contemplates her outfit in the mirror.

A WOMAN sits in the driver seat of an old beige HONDA, staring off into oblivion. This is ELIZABETH (29) – a listless shrinking violet, desperate to be known and undetectable at the same time. She looks PAINFULLY BORED.

Which one did you like best? For me, the winner is Liz Roe, which came from yesterday’s script, Our Condolences. Note how the description is both thoughtful (it uses specific words like “sharp” and “self-possessed”) yet to the point. Usually when I get a character description that’s thoughtful, it’s too long. Ideally, you want it to be descriptive but also succinct.

I also like Bill’s description (from today’s script). His outfit, “paint stained working clothes,” tells us a ton about him. But it’s that second half of the description that really paints a picture.

Note how when the writers try to get too writerly (“a listless shrinking violent”) or cute (“the kind of woman who makes you think you’ve done something wrong with your life”) you leave the intro unsure. Be clear. Be succinct. Use clean words that illicit an image. You do that and you’ll write a good character description.

Genre: Article/True Story

Premise: After having a stroke, a prominent Los Angeles doctor begins rapping, eventually taking his talents to the heart of the Los Angeles street rap scene.

About: This Atlantic article was discovered and picked up by producer Michael Sugar (Spotlight). Sugar will produce the film for Netflix. John Hamburg (I Love You, Man and Why Him), will adapt and direct the film. Jeff Maysh, who likes to write articles that have the potential to become movies, wrote the article. Here’s another of his articles about a unique catfishing story. And another about a wedding used as a drug dealer sting. Neither have been optioned yet. Maybe someone here will change that.

Writer: Jeff Maysh

Details: Article appeared in The Atlantic on January 16th.

We’re doing something different today. As I’ve talked about freely over the last year, spec sales are down, which means you have to be more strategic in the way you approach breaking in. If you’re not writing a contained horror, contained thriller, or guy/girl with a gun spec, you need to be open to new avenues besides the straight spec script.

One of those avenues is to write articles or short stories and post them on the internet, or look for popular articles and stories and try to get the rights to them. This brings up a larger question about what makes a good movie idea. When you read a short story, news article, or Twitter rant, how do you know if it has the weight to be adapted into a feature film? I have the answer for you. But before I go there, let me break down this article.

Dr. Sherman Hershfield was a neurologist in the 1980s and 90s. Then, during the 90s, he started having blackouts. Later, those blackouts would turn into a stroke. And when Hershfield came out of the stroke, something was different. Without trying, everything he said came out in rhyme. Unable to practice medicine anymore, Hershfeld began obsessing over poetry, and, eventually, rap.

One day, when someone heard him rapping on a bus, they told him he should check out Leinhart Park. They had an open mic for rappers there. Anybody could get up and spit rhymes. The only catch was that Hershfield was a 50-something Jewish man. And Leinhart Park was the area where Rodney King got beaten up. To say the area was skeptical of rich white men would be an understatement.

Hershfield went anyway. But when he got onstage, he was far from an immediate sensation. He was more a poet than a rapper. The only reason he didn’t get kicked off that first night was because the crowd felt sorry for him. But Hershfield wasn’t fazed. He began studying the history of rap and practiced every day. Even as his Beverly Hills family became embarrassed of him, he didn’t stop.

One day after performing, Hershfield met rap legend and now mentor KRS-One. KRS-One saw a passion, but more importantly, a unique point of view, in Hershfield. He was bringing a different kind of battle to his music. KRS-One schooled Hershfield on the technicalities of rap, and now when Hershfield went to Leinhart, crowds were looking forward to his performances. He would eventually adopt the moniker, “Dr. Rapp.” Unfortunately, Hershfield’s health began to deteriorate, and after a series of seizures, he would pass away. Still, everyone who knew Hershfield admitted that he was never happier than in those final years where he found and honed his passion of rapping.

So what are you looking for when you option an article?

Two things.

A great story.

Or a fascinating character.

Every once in a blue moon, you’ll find the HG (the Holy Grail). That’s when you find a great story AND a great character. But one is good enough.

Dr. Rapp has the great character. I mean look at all the things that are going on with Hershfield.

You have irony. A rich white doctor who goes to the poorest areas of the city to rap.

You have a fall from grace. A man whose career was derailed by a stroke.

You have a fish out of water story. A white man inside a world he’s totally unfamiliar with (or as someone else put it: “It was like Larry David had wandered into a Snoop Dogg music video.”).

You have an underdog. An older white man trying to make it in a profession dominated by young African American men.

And on top of all of that, you have a role an actor would die for. Why? Because it’s not a role actors of this ethnicity and age ever get to play. When you have a role that actors have never gotten to play before, they swarm to it.

With that said, I knew this had a good character based on the press report alone. An older white man rapping is a unique role. My question going in was, “Is there a story here?” It doesn’t have to be a great story. But there has to be a place to go with the narrative. What’s the destination?

I’m not convinced Dr. Rapp has that yet. But it has some pieces to work with. For starters, I like Leinhart Park itself. It feels like the area is its own character, an entire community of unique personalities. I also like this mentorship between KRS-One and Dr. Hershfeld. I’m immediately thinking of Kevin Hart and Bryan Cranston in The Upside. You’d do something like that.

Where the adaptation has me worried is the stakes. It doesn’t sound like Hershfield did anything outside of become a mini-celebrity within a sub-community. Is that enough? He didn’t make an album. He didn’t break out into the mainstream. What will the culmination of this journey be? That’s the problem with these people you’ve never heard about before. There’s usually a reason you haven’t heard of them.

I suppose you can take the feel-good life-lesson route. Hershfield is dying but he still wants to rap because it soothes the soul. But that still doesn’t tell me where the story’s going to end. What’s the big rap-related event going to be? That question becomes more important when you take into account who’s adapting the material. This is the writer who made one of the worst comedies of the last few years, Why Him. How is he going to nail a character-driven comedy-drama without a clear plot? Even Why Him had a clear end point (the end of the weekend, when the parents were leaving).

But there’s potential here. This might be a case where the right actor comes along, creates a classic character, and that’s all that matters. We’ll see!

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Audiences like watching cultures collide. Remember that the best stories contain conflict at their core. So it’s not surprising that someone would be interested in making a movie where a rich white man attempts to become part of the inner city culture. The conflict is ready to go before you’ve written a word.

Next Monday: Captain Marvel Review! I have a feeling it’s going to get bloody!

Reading through the entries of the First Ten Pages Challenge has been trying, to say the least. I’ve encountered a lot of bad dialogue. I can’t say I’m surprised. Bad dialogue and amateur screenwriting go together like almond butter and marmalade. But I was not expecting to be this underwhelmed. There are a lot of things that go into bad dialogue, the biggest of which is that screenplay conversation utilizes a different set of rules than real life conversation, and new writers have trouble understanding that. For example, if you and I were to grab coffee together, we might chat for 45 minutes. But if we were to grab coffee in a movie, that same conversation would only be 3 minutes.

A huge part of what makes conversation “realistic” is the randomness of it. We discuss one topic, segue to another, go off on a tangent, come back to the original topic. Our thoughts are unrehearsed, rough, messy. In a screenplay, scenes serve a purpose. They need to move the plot forward. Which means the characters must be goal-driven. They might need to convince someone to help them with a task, for example. This means the conversations are artificially focused. Yet they must still feel like real life – they must feel like that 45 minute conversation. Learning to do this takes time and practice. Even when I tell writers what to do they still have trouble implementing it. But that doesn’t mean I’ll stop trying. Here are six dialogue pitfalls I keep running into and how to avoid them.

1) ON-THE-NOSE DIALOGUE – On-the-nose dialogue is when characters say exactly what’s on their mind. “How are you today?” “I feel really bad.” That’s an on-the-nose conversation. Changing the answer to something like “I feel wonderful” with a sarcasm parenthetical fixes the problem. “I was over at Sarah’s. She’s so cool.” “I don’t like her. She’s not a nice girl. Do you have to hang out with her?” “Why are you so mean, mom!” These words could’ve been plucked straight out of the characters’ minds they’re so on-the-nose. To avoid this, look for ways around obvious responses. “Oh my god. You should’ve seen Sarah go off on Mrs. Jensen today. She owned her.” Notice how she says the same thing, that she likes Sarah, without literally saying that she likes Sarah. “Sarah whose mother destroyed the Thompson’s marriage?” Same thing. The mother is saying she disapproves of Sarah without literally saying she disapproves of Sarah. “Love you, mom. I’ll be in my room.” The daughter is showing she doesn’t approve of her mother’s opinion without literally saying she disapproves of her opinion.

2) TRY-HARD DIALOGUE – Try-hard dialogue is dialogue where the writer is trying to make every line epic. It’s writing like Diablo Cody or Aaron Sorkin when your skills are more in line with Freddy First Draft or High Concept Harry. “The world’s a Smith and Wesson and the trigger-happy troglodytes are waiting for the right meat puppet to pump full of common sense, ya hear?” No. I don’t hear. Ever. If you’re one of the .00001% of writers who can pull this type of dialogue off, go for it. For the rest of us, know your limitations. There’s nothing more cringeworthy than a sixth grader trying to convince people he’s a CEO.

3) EXPOSITION-HEAVY DIALOGUE – Exposition is any dialogue that explains mythology, backstory, character, or plot. “Did you hear the Southern California zombies have all been confined to 3B Island?” Mythology exposition. “I still can’t believe dad got turned. It seems so surreal.” This is backstory exposition. “At least he left you his alcohol addiction to help cope with it.” Not a terrible line, but this is conveying that the character is an alcoholic, which makes it character exposition. “We just have to keep it together until the wedding’s over.” “72 hours of misery and we’re free.” This is setting up our plot – the wedding – making it plot exposition. Here are a few things to remember with exposition. One, you sign your own death warrant. If you write something that requires a ton of explaining, like, say, Lord of the Rings, you will be spending the majority of your script writing exposition. If your concept is simple, like Taken, exposition won’t be a problem. Two, cut all exposition by 30% AT LEAST. This will make the reader’s job easier. I’ve found that you can always cut more than you think you can. And three, SHOW exposition. Don’t TELL it. So if a character is an alcoholic, you should never have them say they’re an alcoholic. You should show them drinking.

4) BORING DIALOGUE – Boring dialogue is an epidemic. It can best be described as conversation without life. It is plain, unimaginative, and functional. “Did anyone tamper with the evidence?” “No, it’s clean.” “Get it down to Owens by this afternoon.” “Will do boss.” “And good job.” “Thanks, that means a lot.” That has to be the most boring dialogue I’ve ever written. The best way to combat boring dialogue is to infuse each character with a defining trait. “Sarcastic.” “Juvenile.” “Passive-aggressive.” “Snarky.” “Suave.” “Overly-optimistic.” “Sensitive.” You’d then write their dialogue with that trait in mind. That doesn’t mean EVERY line will exhibit a sarcastic or suave tone. But it will generally be how the character reacts. For example, the “sensitive” character might answer, “Did anyone tamper with the evidence?” with “Why would you ask that?” Which is a way more interesting answer. Go ahead, rewrite this dialogue (extend it if you want to) in the comments using defining traits. Make sure to let us know which traits you used afterwards.

5) WEAK CHARACTERS – The most overlooked reason for weak dialogue? WEAK CHARACTERS! Lame average people don’t have anything interesting to say in real life. So why would that change for fictional people? Show me a movie with great dialogue and I will show you key characters in the movie who were either funny or unique or offbeat or polarizing. That doesn’t mean every character in your script has to be a Tower of Crazy. But a few of them need to stand out. One great character (Hannibal Lecter or Captain Jack Sparrow or Queen Anne in The Favourite) can be the difference between a movie with average dialogue and a movie with great dialogue.

6) DIALOGUE WITHOUT CONFLICT – The great thing about conflict is that it can generate kick-ass dialogue all on its own. You don’t even need great characters if you do it right. As I’ve told you before, a scene that always works is having one character who wants to talk and another character who doesn’t. That dynamic always generates an interesting conversation. Or look at the movie Swingers. The characters disagree with each other in EVERY SCENE. Mikey thinks they should be nice to the girl. Trent thinks they should be assholes. Or elephant-in-the-room conflict. There’s an elephant in the room that your characters aren’t discussing. That bleeds into the conversation, as each line is like taking a step through a minefield. If your dialogue is weak, chances are you’re not adding enough conflict.

Carson does feature screenplay consultations, TV Pilot Consultations, and logline consultations. Logline consultations go for $25 a piece or 5 for $75. You get a 1-10 rating, a 200-word evaluation, and a rewrite of the logline. If you’re interested in any sort of consultation package, e-mail Carsonreeves1@gmail.com with the subject line: CONSULTATION. Don’t start writing a script or sending a script out blind. Let Scriptshadow help you get it in shape first!