Search Results for: F word

Genre: TV Show – Hitchcockian Thriller

Premise: A secret military program in Florida prepares soldiers coming back from the war to effectively integrate back into society.

About: Homecoming started off as a podcast and gained a lot of publicity at the time as it was the first podcast that had attracted big name talent to the medium (Catherine Keener, David Schwimmer, and Oscar Isaac were featured players on the show). Universal would later secure the rights for TV. From there, Sam Esmail (of Mr. Robot fame) came on to run the show, and Julia Roberts signed on to be the featured star. Amazon debuted the show this weekend. The original creators of the podcast, Eli Horowitz and Micah Bloomberg, did much of the writing for the TV version as well.

Writers: Micah Bloomberg & Eli Horowitz

Details: 10 roughly 30 minute episodes

I’m a HUGE fan of Sam Esmail. I’ve been reading his scripts long before he became one of the hottest names in town (as the creator of Mr. Robot). If you’re ever frustrated about whether you’re going to “make it” or not, I saw this guy spec out script after script for a good 7 years. Everybody thought he was talented, but they all felt his scripts were too voice-y or weird to get made. TV turned out to be the perfect arena for him as it allowed him to play with his weird sensibilities without having to wrap all the weirdness up in one go. So I’ve been looking forward to this as soon as I saw the trailer. I mean, the only other person who’s gotten Julia Roberts to do TV in 30 years was her ex-husband. So you knew this was heavyweight material. Or, at least, that was the assumption. Is it heavyweight material? Let’s find out.

Heidi Bergman has been brought in as a psychotherapist in a new military program that helps soldiers returning from the war. Her job is pretty simple. She sits down with each of the soldiers throughout the week and listens to their stories about the war. Her main patient is a gentle African-American man named Walter Cruz. Cruz seems to be the opposite of what you’d expect a soldier to be after returning from a war. He’s kind, he’s sweet, he’s funny. Heidi enjoys her sessions with him.

Meanwhile, Cruz’s closest friend in the unit, Abel, thinks this whole program is sketchy. They’re being kept in this mysterious building. There’s no one else around for miles. They’ve been told they’re in Florida, but he points out that they have no direct evidence that that’s the case. He goes so far as to say they’re still in the Middle East and that the U.S. created this fake facility to trick them. Cruz thinks his friend is going loco. But in the back of his head, he wonders if there’s some truth to the theory.

Occasionally, we jump forward several years, where Heidi is now working as a waitress at a dingy marina diner. It’s there where a strange investigator, Thomas Carrasco, approaches her, wanting to know about the failed program, dubbed, “Homecoming.” But Heidi’s moved on from that world and tells Carrasco as much. She doesn’t remember much and labels the entire program uneventful. Carrasco’s bosses likewise tell him to give up. But just as he’s going to close the file, he decides to dig deeper. He’s convinced that something nefarious is at the bottom of the Homecoming file.

The problem with Homecoming is its lack of a hook. It wants you to think it has a hook. A mysterious program that helped military veterans which has since been abandoned. But the program itself isn’t that interesting. The pilot tries to tempt us by implying these men have a high proclivity towards violence. One of the scenes attempts to prepare the men for the real world by staging a mock job interview. During the interview, one of the vets loses his shit and starts fighting another soldier. It’s supposed to be a highlight scene and yet the only thing I could think afterwards was, “So you’re saying military vets have PTSD and a proclivity towards violence? Wow. Cutting edge theory you’ve put together there.”

The moment I suspected this show was in trouble was the last scene of the pilot. Remember, the final scene in a pilot must work double duty. It has to wrap up the pilot, but also introduce a cliffhanger to make us want to watch the next episode. Homecoming’s final scene takes place 3 years after the program. Heidi now works as a waitress in a diner. The investigator pulls her outside to ask her what she remembers about the program. The scene is positioned as if some giant bomb is going to be dropped at any moment. He’s probing what she remembers. She tells him it was just a job. Finally, there’s a dramatic pause, and he asks, “Do you remember William Cruz?” William Cruz is the soldier she spent the most time with. Another dramatic pause. And then she replies, simply, “No.”

And that’s the end of the pilot. That’s our big wowza cliffhanger: Heidi denying that she remembers William Cruz.

I’m sorry, but, that doesn’t get me back in the door. You need something WAY BIGGER. You need an exchange closer to… HEIDI: “I’ve already told you. I don’t remember much.” INVESTIGATOR: “Anything will help. Anything at all. Walter Cruz. Do you remember him?” HEIDI: “Why are you even asking me this? I’ve moved on.” INVESTIGATOR: “Because every soldier in the Homecoming Program… is now dead.” He stares at her, gauging her reaction. We can see she’s shocked by this but trying to hide it. “I’m sorry, I have to get back to work.” And then she goes inside.

Look, I’m not saying that’s the greatest cliffhanger ever. But at least NOW YOU HAVE A SHOW. Now I want to know what happened to these guys. Now I want to know what this mysterious program is about. And the only way I can find answers to these two questions is to keep watching. Why would I want to keep watching a show just because Julia Roberts lied about remembering one of the soldiers?

Also, the podcast format doesn’t adapt nicely to television. Or, I should say, they didn’t figure out how to adapt it to television. Obviously, a podcast is going to have a lot of talking. It needs to fill up the dead air. But TV is a visual medium. It works better when it’s showing, not telling. And to Esmail’s credit he does some cool things visually. There’s one shot early on that follows Roberts through the entire facility from above.

But there are just as many problematic moments, such as Heidi’s silly boss who calls her all the time and babbles on endlessly without ever really saying anything. I’m sure in the podcast format, this non-stop babble worked well, since it killed a lot of minutes. But watching it becomes tiring, particularly since, like I said, he’s not saying anything. He’s just filling up space with words. It wasn’t until the fifth boss-phone monologue, in the third episode, that he actually introduced a plot point, which was that they were secretly administering medication to the soldiers in their meals. Your ratio of talking to plot points shouldn’t be 1000 to 1.

I remain unconvinced that creators know what to do with the new streaming format. Are they treating it like TV? Are they treating it like movies? Because if you’re treating it like one long movie, then sure, you don’t need a big cliffhanger at the end of the pilot episode. But I’d argue that any situation whereby you leave it up to the watcher to find and click the next episode means that if you didn’t hook them, they won’t click. In other words, traditional TV rules still apply.

With all of that said, I don’t think Homecoming is a failure. It’s certainly more interesting than most of what you’ll find on TV. The score is weird. It has its share of fun visual gags (my favorite was an old warehouse with an antiquated/futuristic motion detector, so that the dusty old lamps light up and turn off one at a time as you walk through the building – BZZZZ-POP, BZZZZ-POP). Esmail loves top play around with the camera. And Roberts is always hard to look away from. I guess I wanted this to be great. And I was disappointed that it didn’t live up to those expectations. But you could certainly do worse.

[ ] What the hell did I just watch?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth checking out

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Never write scenes because you need to fill up time. Write them because they are necessary to move the plot along. This boss character who calls Heidi all the time – 95% of what he says is absolutely meaningless. He’s just there to be the babbling boss who eats up minutes. Audiences get bored quickly. Don’t make it easy for them.

Don’t do it don’t do it don’t do it don’t do it. These are the words that have been assaulting my brain every hour for the last seven days. That would be when Red Dead Redemption 2 came out. Since then, I’ve gone to Amazon.com every hour on the hour and stared at a sleek picture of a brand new Playstation 4. Don’t do it don’t do it don’t do it don’t do it. I’ve wanted a Playstation 4 forever. But I’ve specifically not purchased one because I know I’ll waste hours of time with it. That plan has worked up until seven days ago. But every time I see a commercial for that rootin-tootin freakin video game, I want to buy it. I want to roll in its digital dirt. I want to swim in its plethora of pixels. So far I’ve held off. But I don’t know how much longer I can last.

Luckily, I found a Western for this week’s amateur offerings. That’s helped some. As for the rest of the scripts, we’ve got an electric variety. Pilots. Comedies. Thrillers. Oh, and one of these “Why You Should Reads” is quite inspirational. A lesson in assertiveness and exploring every contact you’ve got, no matter how small it seems. Check it out!

If you’ve never played Amateur Offerings before, you’ve been deducted 4 Scriptshadow points. A vote from you could mean the difference between a screenwriter starting his career and spending the rest of it in obscurity. Read as much of each screenplay as you can. Afterwards, cast your vote for your favorite script in the comments section. Voting closes on Sunday night, 11:59pm Pacific Time. Winner gets a review next Friday. — If you’d like to submit your own script to compete in Amateur Offerings, send a PDF of your script to carsonreeves3@gmail.com with the title, genre, logline, and why you think your script should get a shot.

Good luck to all!

Title: Bricks of Glory

Genre: Sports Comedy

Logline: In the fast-rising sport of Bricklaying, an anti-doping agent and disgraced former champion must take down the champion’s former nemesis, who they suspect is using a bricklaying-enhancement drug known as “Brick Dust.”

Why You Should Read: Bricks of Glory was inspired by a real life event called the Bricklayer 500 which takes place in Vegas every year. They take the top 20 bricklayers from around the world and compete to see who can build the highest (and most structurally sound) brick wall in 60 minutes. A friend of mine’s husband won the Regional Competition in my area so I went to Vegas to watch the show and attended the World of Concrete convention as research. Man, what a trip. I mean they seriously treat this like a major sporting event! I find it so hilarious! So in my script, I completely exaggerate this and make it a much bigger, funnier, spectacle of a sport. Bricklayers use flair, like lighting their walls on fire and juggling bricks, and the competition is so fierce, they resort to taking performance enhancing drugs. I’ve put a lot of work into this script, even doing table reads with stand up comedians to help me punch up the jokes. But if you want to see what inspired it, here’s a video recap of the Bricklayer 500 which should sell it better than I ever could: https://youtu.be/zR69ZFdldH0

Title: The Boom

Genre: TV – One Hour Drama

Series Logline: In the early 2000s, dreamers, misfits, prodigies, and hustlers swarm to Las Vegas in search of fame and fortune during the birth of the poker boom.

Pilot Logline: After becoming an online poker sensation, a gambling addict goes to Vegas to try his hand at the real thing, meanwhile a tortured ex-gangbanger kidnaps his cousin, a sports-betting prodigy, and drives him to the same casino hoping to capitalize on his skills.

Why You Should Read: In 2003, an amateur poker player named Chris Moneymaker won the World Series of Poker, sparking a massive increase in poker play all over the world. College students became millionaires playing online poker and moved to Las Vegas to live it up, while the existing live pros became celebrities. The Boom seeks to leverage the unique stories and characters from this time period to create the first ever series which chronicles the lives of professional gamblers in Las Vegas. It’s an ensemble similar to The Wire in that it follows a wide variety of characters and not all of them cross paths. The pilot starts with an 11 page prologue that culminates with the event that launches the series and from then on follows two separate storylines featuring four main characters, all struggling to survive in Las Vegas at the start of the poker boom. One of the things I’m most proud of with this pilot is that non-gamblers have found it accessible—so if you don’t know a thing about poker, please don’t let it prevent you from reading!

Title: Legal Pursuit

Genre: Comedy

Logline: A mocumentary following the legal exploits of the personal injury law firm Fraud, Trick & Brown and their pursuit of fortune, fame and sometimes justice.

Why You Should Read: In America today if you accidentally nail your hand to a wall because of a faulty nail gun, you’ll want to sue the nail gun manufacturer and there are plenty of lawyers that’ll nip at your heels for the case. However, if your teenager went to the hospital for eating a Tide Pod and you want to sue the detergent company for a lack of warning not to eat it, who are you going to call? You’re going to need a more ethically flexible attorney willing to blame someone else for you.

Legal dramas tackle social injustices, changing times, and debates about what real justice is and how the law should work. Legal Pursuit is a half-hour single camera comedy that shows how the legal system sadly works and follows the attorneys of Fraud(pronounced Freud), Trick and Brown. The lawyers that’ll lie, cheat and manipulate everyone they can to defend you in court and split the settlement 70/30… 60/40… Fine: 40/60!

Desperate for business in this bad economy, each client is a potential win that will keep the lights on for one more week, get them that fancy electric car, pay off their new boat or afford them a vacation to Hawaii. Oh! Legal fees, surprise witnesses and experts need to be covered too! Enjoy! And if you don’t, I’d love to hear thoughts from the SS community to help make this the best it can be.

Title: THE SHADOWED

Genre: Horror-Western

Logline: An outlaw and his gang must team-up with a company of Texas Rangers to battle with the resurrected ghosts of vengeful Navajo braves besieging an isolated border town.

Why You Should Read: My script was shortlisted in The Tracking Board’s Launch Pad competition, allowing me to become a TB Alumni. I wrote the script after chatting with stuntman Ian Van Temperley, who hoped to be able to do the horse stunts for The Shadowed if it ever went into production. Whilst doing the stunts for the TV series Galavant, Ian Van Temperley shared my Shadowed script with the show’s creator Dan Fogleman. Dan read the script and wrote back saying this: “Dan Fogelman here from Galavant. I wanted to let you know that I read your script and was very impressed! The best thing about the script was the outlaw character Wakes, along with how well your action sequences were not only crafted, but written. It’s a very hard thing to do well, and you clearly know how to describe them. Most action sequences get hard to follow and hard to “read” – that’s not at all the case here. You have a great main character and a terrific action movie here. I enjoyed reading it.”

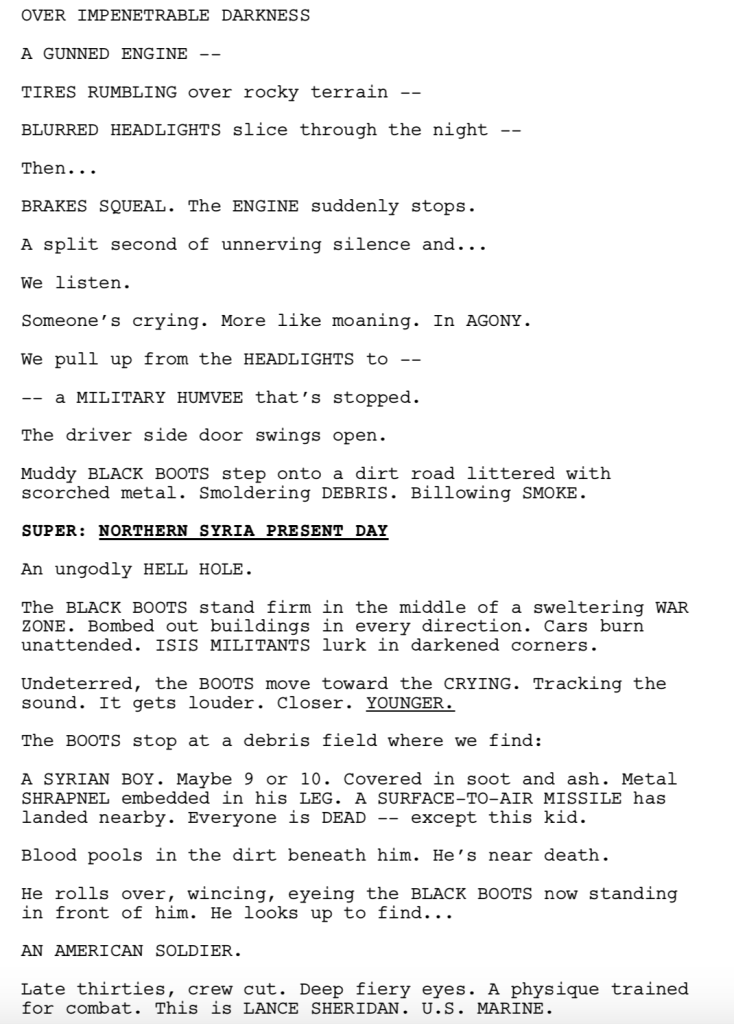

Title: Endangered 6

Genre: Thriller

Logline: After a widowed U.S. war vet and his estranged daughter check into a Manhattan hotel to reconnect, they soon find themselves alone and trapped in the building only to discover they’re at the center of a terrorist conspiracy that will kill hundreds on the streets of Manhattan, but they’re the only ones who know… or have the power to stop it.

Why You Should Read: I’ve been honing my craft for a while and have a few specs on the hard drive to show for it. This one was a finalist last year in a thriller screenplay contest and I’d like to see how it might do here with the Scriptshadow crowd. When I set out to write this my goal was to write a fast paced thriller with a broken relationship between a father and daughter at its emotional core. It’s Panic Room on steroids. Hope you feel the rush too!

Here are 10 lessons born out of the mistakes I’ve seen in the last 10 scripts I consulted on.

TAKE AT LEAST ONE BIG CHANCE – The most common script I read is the by-the-book script. It’s set in a familiar genre – horror, thriller, western – and it stays very comfortably within the rules of that genre. It never strives to do anything unique. There’s a fear of coloring outside the lines. These scripts can be decent. But they can never be great. Take one big chance. We know how I felt about Hereditary, but they definitely took a huge chance (spoiler) by killing off the daughter the way they did in that film. And people in The Matrix only fight via… Kung-Fu? I don’t think the average writer realizes how big of a risk that choice was.

PUT SOME BAD IN YOUR GOOD CHARACTERS AND SOME GOOD IN YOUR BAD CHARACTERS – When you hear the words, “on the nose,” in reference to one of your characters, you know you’ve failed. Here’s how to prevent that. For your heroes, give them shades of darkness. And for your villains, give them shades of goodness. “Good” character in The Looming Tower, Jeff Daniels, was determined to rip through red tape to take out terrorists and protect America. In the meantime, he was sleeping with several women besides his wife. That’s how you write a complex character.

FIGURE OUT A WAY TO MAKE YOUR HERO ACTIVE – One of the hardest things for a script to overcome is a passive hero. Audiences don’t like passive people. Active people drive stories. So whatever you can do to make your hero active, do it. I just read a military script where the main character was a soldier. And throughout the story, he was passively doing as told. Technically, this makes sense. Soldiers have to follow orders. But it doesn’t work for the story cause the hero is forced into the background. Chris Kyle was a soldier in American Sniper. But I’d never call him passive. Figure something out so that your hero is active. Cause it’s too hard to make a script work otherwise.

DON’T BE AFRAID TO CHANGE THE GOAL DURING THE SCRIPT – Movies can become boring if we know the goal from the first page to the last. There’s ways around this (namely, writing great characters). But if you want to hack the problem, change the hero’s goal at some point during the story. This keeps the reader on their toes, as it keeps the story fresh. For example, Star Wars starts out with the goal of delivering R2-D2 to Princess Leia’s home planet. But later, the goal switches to destroying the Death Star.

LAZY FIRST SCENES – This one drives me nuts because it’s one of the first things they teach you when you get into screenwriting. Write a killer first scene. Hook the reader immediately. And yet, in 9 out of the last 10 consulting scripts I’ve read, the writer didn’t follow this advice. I’m not saying all the scenes were bad. Some were pretty good, actually. But only one gave me the impression that the writer understood just how important the first scene is. He really went for it. I would implore you to think of your first scene as its own separate screenplay. Because it basically is. It’s the resume that lets the employer know that you’re worth knowing more about. You should be treating your first scene like it’s a life or death scenario. If you don’t hook the reader, you die.

DON’T OVERREACH – Be realistic about what you’re capable of. One of the problems writers make is they pick a really complex script or really complex subject matter, and they either don’t have the chops to nail it yet, or they don’t want to do the research required to make something like that work. For example, if I came up with an awesome idea about black market Russian nuclear warhead sales during the Cold War, I would never write it in a million years because I know I would have to do so much research to make that story feel even remotely authentic. I literally know three words in Russian. I couldn’t point out Moscow on a map of Russia if you gave me five guesses. And I’m going to write an intricate story about nuclear espionage in Russia 40 years ago? Part of being a good screenwriter is understanding your limitations. Yes, you want to be pushing yourself. But don’t be unrealistic. The best scripts are often scripts where the writer is insanely comfortable in the genre and story they’re telling.

CLARITY ISSUES – Clarity should be a given. I should never be confused about how two people know each other, where we are, what’s going on in a scene, what the basic geography is. I find that the writers who have the biggest problems with clarity are the ones who don’t read a lot of scripts. Make sure you’re reading scripts! And read AMATEUR SCRIPTS too. That’s where you’ll be confused yourself. You’ll then be less likely to make those mistakes in your own script.

HALF-BAKED MYTHOLOGY – There’s a huge difference between extensively built mythology and half-baked mythology. Watch The Matrix. Then go watch Tom Cruise’s The Mummy. Notice how carefully woven together the mythology of The Matrix is. You know that there are zero holes. It’s been broken down then built back up a hundred times (the first film, not the sequels). The Mummy, meanwhile, is all over the place. Nothing really makes sense. We’re not quite sure what the rules are. So if you’re writing a fantasy or sci-fi or horror script, do the work on the mythology. If you half-ass it, believe me, the reader will know.

NOT ENOUGH CONFLICT IN SCENES – The scripts that I have to fight to stay awake during are the ones where there’s little conflict going on. There’s no major conflict between the characters. There’s not a lot of conflict in the dialogue. There’s not a lot of conflict in the plot. Things tend to go easily for the characters. They don’t have to overcome major obstacles. Or, if they do, the obstacles are easy to defeat. Look to add conflict in every single scene. Remember that the reader feels a need to keep reading as long as there’s something unresolved. So if there’s conflict (an unresolved issue) in every scene, there’s always a need to keep reading.

EXPLOIT YOUR CONCEPT – Whatever your concept is, exploit the hell out of it. That’s what’s unique about your script. So you shouldn’t be focusing on other stuff. Every ten scripts or so, I’ll read a script with a really high-concept premise, but it reads like every other script I’ve read, namely because the writer’s inserting generic copy scenes from similar movies as opposed to exploiting the premise. Watch the trailer for the new film “Isn’t It Romantic.” The idea is that a woman wakes up in a romantic comedy world. You can see here that every scene of the trailer highlights that. Whether you like the idea or not, you can’t deny that the writer is mining it for everything its got. That’s what you need to be doing with your idea.

Genre: Horror

Premise: (from Blood List) Based on TRUE EVENTS. In response to this “astonishing” increase in demand for exorcisms, the Vatican opens a secret exorcism training academy where a young, gifted nun defies the church leadership to join her colleagues in the battle of good versus ultimate evil.

About: Today’s script finished numero TWO on this year’s Blood List. Robert Zappia has been writing for over 25 years, and actually wrote an episode of Home Improvement, which made him the youngest writer ever to write an episode for a number 1 rated show.

Writer: Robert Zappia (story by Earl Richey Jones & Todd Jones & Robert Zappia)

Details: 100 pages

It used to be that exorcism scripts were the best bang-for-your-buck sub-genre out there. Think about it. All you needed was a camera, a bedroom, and an actress willing to act crazy and you had a movie. These 500,000 dollar productions could fetch up to 30 million bucks at the box office. 600% return on your investment? Who doesn’t want that?

But either the public got sick of exorcisms or screenwriters ran out of ideas, because I can’t remember the last exorcism movie that was any good. Something-Something Emily Rose Exorcism? Is that what that one was called? It seems that audiences have gotten hip to the fact that someone writhing around in agony and screaming bad words isn’t must-see cinema. But with every dead genre, there’s an opportunity for a clever writer to reinvent it. Has today’s author done so? Let’s find out.

There has been an “unprecedented” rise in reported demonic possessions. This has resulted in the Pope setting up exorcism schools across the world. One of those operates in the United States. And this is where we meet Sister Ann, a nun in an affiliate church who doesn’t follow the rules. Ann, as is the case with all women, isn’t allowed to take any exorcism classes. But she does anyway!

One of the teachers, Father Quinn, takes exception to this, and warns Sister Ann that if she comes to another class, she will be expelled. Sister Ann ain’t no pushover, so she makes her case, but in the end agrees to leave it alone. That is until one of the priests runs into danger during an in-patient exorcism. Sister Ann runs into the room and bullies the demon back inside the patient, saving the priest’s life.

When Father Dante sees this, he asks Sister Ann to secretly come perform an exorcism on his pregnant sister. The school did not find sufficient evidence to label her sickness a possession, which is why he can’t go to anyone else. Sister Ann goes, only for things to go disastrously wrong. Ann gets kicked out of school. But only a few weeks later, they come back to her. It seems as if someone is possessed by a demon Ann has a special relationship with. Will this be her redemption? Does she want it to be?

What’s DIFFERENT about this script? That’s the first question a reader asks. And actually, it’s better if the reader doesn’t have to ask it. They should know immediately. They should feel this is different without having to ask why. There’s two things that are different here. A female exorcist and the movie takes place in an exorcism school. The next question the reader asks is, “Is that enough?” Is it enough to build a movie around a female exorcist in this setting?

I’ll say one thing. It’s smart. This is the market we’re in right now. Find the female angle. And it’s best if the angle exploits something that, traditionally, women haven’t been able to do. A female buddy-cop team-up isn’t that inventive because women have been able to be cops for a long time. But women have never been allowed to perform exorcisms. So it truly is giving us something fresh.

The final question a reader asks is, “Does it work?” And, ultimately, that’s the only question that matters. You can make all the arguments you want about why your idea is awesome. But if it doesn’t work on the page, it doesn’t work. To that I’d answer, Devil’s Flame sorta works? But not for the chances taken above. More so for the exorcism scenes, which are fun. There’s a scene, for example, where a possessed girl’s long matted hair has been slung around and shot deep into her throat. The priest is pulling on the hair, like a rope, grip-pull, grip-pull, trying to get it out, trying to prevent the girl from choking, until we finally see a demon’s hand emerge from the mouth, holding the other end of the hair, pulling as hard as it can back into the body.

Sweet.

The problem with Devil’s Flame is that the setting where the majority of the film takes place isn’t scary. We’re at an Exorcism School, and therefore all the possessed patients are kept in well-guarded, carefully insulated observation rooms. It’s a far cry from some of the exorcism scripts I’ve read where the priest has to travel to an isolated house in the middle of Romania or something. Out there, no one can hear you scream. Here, you have the entire school on call if something goes wrong.

And to Zappia’s credit, he knows he has to offset that. So he makes the exorcisms really intense. Almost to the point where I’d forgotten where we were. But still, it’s hard to make something scary when the setting is built specifically to make it not scary.

Zappia tries to remedy this by giving Sister Ann a backstory that has her seeing ghosts and demons around the halls. And to a certain extent, it works. But it doesn’t work as well as when we’re in the middle of nowhere, which is a staple of good horror. For example, Get Out doesn’t work if it’s set in the city. It only works cause it’s in this quiet isolated town where you get the feeling that all the neighbors are helping the bad guys.

I also think that further drafts could explore the theme of why priests don’t believe women can do this job. There’s a moment in the last possession where the demon possessing the person is saying these horrible awful things to Ann about her sexual past. And I felt like that should’ve been explored early and often – this belief that women can’t “handle” what the demons throw at them. Ann then being able to stand up to and conquer the demon in that way, would’ve placed emphasis on this theme of not underestimating women.

This is a tough call because the script has its strengths. But, in the end, it didn’t take enough advantage of its unique attractor, the female exorcism angle. Bump that up and there’s something here.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Hollywood is looking for more female-driven movies. If you’re going to take advantage of that, do it like Devil’s Flame did. Find a job that women aren’t supposed to do, and make it about the first woman to do it. That’s better than finding a movie that had a famous male role and switching it to female. For example, you want to avoid Rodney Dangerfield in Back to School being changed to Melissa McCarthy in Life of the Party.

Great teasers are expected in horror scripts – When you write a horror film, you HAVE to write a great teaser scene. It’s expected. The teaser in 2018’s Halloween was the most memorable scene in the film. And the same can be said for this Halloween – a boy wearing a mask murders his naked sister in POV. If a horror script gives me a lame teaser, it’s a guarantee that the rest of the script is going to be lame as well.

Bodies in motion – I like when scripts start with something HAPPENING. The characters are IN MOTION, on their way to something. In contrast, bad scripts often begin with characters sitting around. Nobody wants anything. Nobody’s trying to do anything. This sets the tone for a slow dull movie. Get your characters moving after the teaser, preferably doing something that sets the story in motion. After the teaser in Halloween, we cut to Dr. Loomis and a nurse in a car driving to the mental institution to talk to Michael. We’re off to the races already!

Save the Cat still works! – If you’re ever in doubt about whether your hero is likable enough, give them a Save the Cat! scene. It doesn’t even have to be some big production. Like saving an old woman from getting hit by a car. With Laurie, it’s a simple scene where she runs into the boy she’s babysitting that night. The boy clearly loves Laurie, and she’s adorable with him, adhering to all of his demands (watch a movie, make jack-o-lanters, read to him, make popcorn). It’s a short scene, but just like that kid, we now love Laurie as well. The scene speaks to the power of simplicity in storytelling, as pretty much every choice in Halloween is a simple one.

Build build build – In a horror movie, you don’t want your killer to start killing people right away. You want to BUILD towards it. Tease it. Draw out the suspense. Someone’s broken into the local hardware store and stolen a bunch of stuff. Laurie sees a strange figure in a mask standing across from the school. Then a couple of additional times, behind a bush, and in her yard. We’re building building building before the terror is unleashed.

The scariest things don’t have to be complicated – The reason Michael Myers is still terrifying after 40 years is that he’s so simple. A killing machine in an expressionless mask who never says a word. I bring this up only because people think today’s characters have to have really elaborate backstories and motivations. And while that works when done well, sometimes all you need is a simple terrifying monster.

Horror works best under a tight time constraint – Halloween takes place in less than a day. The majority of it takes place in real time. That’s when horror cooks the hottest, when the threat is so immediate that your characters have to deal with it NOW.

Integrate both active and passive storylines – One of the problems with these horror-slasher screenplays is that the victim is passive. Laurie doesn’t know that this man is after her. So she can’t go after anything herself. All she can do is live her life, and unfortunately, our lives are pretty boring. The solution to this is to add an active storyline. This is usually done by bringing in a policeman or detective who’s chasing the bad guy. Halloween does it with Dr. Loomis. He knows Michael will go back to Haddonfield, which is why he goes back there, to try and catch him. This allows you to cut back and forth between Laurie’s passive storyline and Dr. Loomis’s active one.

Dramatic Irony Alert – Remember that dramatic irony is when the audience knows something the character does not. It’s a device you should be using a lot as a horror writer. After Michael kills the guy who’s gone to grab a beer for his girlfriend, Michael puts on a sheet and walks upstairs to the girlfriend, who’s waiting in bed. She giggles when she sees her “boyfriend” in the sheet, and asks for her beer. WE know this isn’t her boyfriend. SHE does not. Hence the dramatic irony. This allows us to squirm and scream, desperately hoping she’ll find out before it’s too late.

The False Kill – Nearly every horror movie has a false kill of the monster/killer near the end of the film. Unfortunately, audiences have gotten hip to this and don’t believe it anymore. “Make sure he’s dead!” they’re screaming as the hero ignores this obvious advice. So if you’re going to do this these days, you want to use every trick in the book to convince the audience the monster is dead. That way, when they come back, we’re genuinely surprised. Unfortunately, Halloween is not one of these movies. Laurie weakly stabs Michael, who falls down behind a couch, and Laurie assumes he’s dead without even checking. Of course, only minutes later, he’s back on her trail.

We’ll forgive a basic plot if we like the hero – Yesterday I said that a cool plot cannot survive weak characters. The opposite is also true. A bad plot can be saved by strong characters. And when I say “characters,” I’m really talking about your hero. This might be the biggest screenwriting hack of all. If you give us a hero we really like, we’ll pretty much forgive everything else. Everything in Halloween is predictable. A killer escapes a mental institution. Some teenagers are baby-sitting that night. The killer finds them and kills them one-by-one. That’s basic horror movie 101. But we like Laurie so much that we don’t need a big fancy plot with lots of twists and turns. All we want is for her to survive. If that happens, we’ll have enjoyed the experience.