Search Results for: F word

Last year, in anticipation of the upcoming Star Wars films, I invited anyone who wanted to send in their own Star Wars script to do so. I would review the Top 5, and if one was really awesome, who knows, Disney might see it and get the writer involved in a future installment of the series. I received 20 Star Wars scripts in total. This week, I will review the best of those. Monday we got Old Weapons. Yesterday we had rising shadows. Today we have the most badass lobster in the galaxy!

Genre: Sci-fi

Premise: (from me) Months after the Empire has been torn down, Admiral Ackbar and a small derelict crew chase after the last Star Destroyer, which harbors an opportunistic commander who may or may not have ties to the Force.

About: This is actually the first script I’ve received from Scott F. Butler, so I don’t know much about him other than he really likes Admiral Ackbar!

Writer: Scott F. Butler

Details: 124 pages

In the name of Salacious Crumb, I don’t know if Star Wars Week is going to survive past today. I’m getting a lot of e-mails from people excited I’m doing it, but not a lot of those people seem to be participating in the discussion. In a half-stolen line from one of the commenters, the comments section for this week is starting to look like the Dune Sea.

With that in mind, I had to make a hard decision on which Star Wars script would be the last. I couldn’t make it through another 150+ page script, so that eliminated Children of the Jedi. I liked that someone would tackle an Emperor origin story. But Holy schnikees, the first five pages are all description! Not even action description. Just description.

That left me with The Admiral’s Vendetta versus Secrets of the Ancients. Admiral’s Vendetta got a little more love in the Group Posting on Saturday, so I decided to go with that.

Strangely, our author has decided to title this episode “Episode 6.5.” I found that odd, since it relegates the script to “never having a chance” status (who’s going to spend 200 million dollars on a half-sequel?). Then again, since Disney has already mapped out an outline for the next three films, none of this week’s scripts had a shot at a direct translation anyway. It was more about finding a writer who could nail a Star Wars story and getting them noticed.

So “Vendetta” takes place six months after Return of the Jedi. The Rebels are trying to clean up the galaxy, and Admiral Ackbar (that iconic lobster looking dude with the awesome voice) has spotted the last of the Star Destroyers trying to get away. He wants to bring in the ship’s commander and, not unlike they did with all those Nazis, make him pay for his war crimes.

The commander in question is a dude named Ti Treedum, who seems to have a little of the Force in him. Treedum is actually a pretty interesting guy. He never saw eye-to-eye with the Emperor, but he doesn’t like the Rebels either. He sort of wants to start his own government, and to do that, he needs to learn how to become a Jedi, something he can accomplish with the help of one the Emperor’s Imperial Guards.

So he and this guard head out to meet up with another bad guy who, I believe, is going to help Treedum get his Jedi schwerve on. Admiral Ackbar is so set on making sure this doesn’t happen, however, he eschews the red tape that would prevent him from following them and goes rogue, teaming up with an upstart pilot named Lanza, and a pirate named Kara Kara.

They take the WA-77 pirate ship (piloted by a humanoid lizard named Slay who speaks in slithers) and are finally able to catch up to Treedum and his Imperial Guard pal. It’s there where Ackbar demands that Treedum turn himself in, but as you might imagine, Treedum has other plans. A battle ensues, which will end with the future of the galaxy in doubt!

The Admiral’s Vendetta felt like one of those scripts with good intentions that hadn’t figured itself out yet. And a Star Wars movie is not the kind of movie that works un-figured-out. There are so many aliens and so many planets and so much exposition and so many storylines, that if you’re not on top of your game and telling a confident story every step of the way, the story can quickly get away from you.

This happens with any complicated story really. For complicated stories to work, you need to workshop them. You need to give them to people after every draft and see if what you’re trying to do is making sense, if it’s all followable. One wonky or confusing plotline can doom a script. Which is why, I’m realizing, writing these Star Wars scripts is so hard.

For example, I didn’t understand what Ti Treedum was really. Was he a Jedi? Or just someone who wanted to be a Jedi? In one scene he’s able to use his force-powers to choke Lanza. In the next, he’s baffled about lightsabers. That’s fine if he’s an apprentice, someone with Jedi powers who’s trying to learn to become a Jedi (or a Sith) but that needs to be made clear somewhere.

See, with every unclear plot point, there are repercussions, “cracks” if you will, that spread out throughout the rest of the script. Because I wasn’t sure if Treedum was a Jedi, I wasn’t sure what he was trying to do. And because I didn’t know what he was trying to do, I didn’t know why it was so important for Ackbar to get him. This entire script is based on Ackbar’s need to capture Treedum at all costs. But if Treedum’s just some bumbling wannabe-Jedi, who cares? How much damage can he really do?

And that was “Vendetta’s” biggest mistake. The stakes weren’t very high (or clear for that matter). What happens if we stop Treedum? Nothing, really. We stop some unclear future problem. In Star Wars, we’re trying to stop the most technologically advanced weapon in the universe. Those are stakes. Had, for instance, we been told that Treedum was a super badass with the ability to raise armies and take over the galaxy, I would’ve been more invested in stopping him.

On top of that, there were too many meandering sequences in the story. Remember, sequences in action movies are about setting a goal, stakes, and adding urgency. They’re little mini-movies that need to be clear. In the original film, our characters get stuck in a Death Star. It’s clear their goal is to get out. That the stakes are they’ll die (along with many others). And the urgency is that someone’s always on their tail.

When we finally get to Treedum’s ship, there’s this overlong sequence where we’re just sitting around with the two ships (good guys and bad guys) talking to each other. “You surrender.” “No, I don’t want to.” It felt like a petty fight between five year olds. This is Star Wars. There should be no ships talking to each other through video-links. People need to board ships, to go after people, to get into some conflict!

And when conflict did finally arrive, it dipped up and down in waves. A sequence has to build up to a climax (again, our characters in the Death Star – they’re building towards getting out – the climax occurs when they make their run for it). There was no build here. It was, again, a lot of back and forth, as if Scott wasn’t quite sure if, or when, he should pull the trigger.

That might be the best way to describe “Vendetta.” The script always felt like it was holding back. It never had its “stuck in a trash compactor” moment. The conflict was only half-realized. I wanted these characters to engage, but it seemed like they were more interested in talking about engaging.

That’s not to say the script didn’t have its moments. It was probably the most creative of the bunch. The half-underwater city of Dac was really cool. And the port city with all the pirates where they had to find a ship, although an obvious reference to Tatooine, felt like its own unique world, which is what I’ve been looking for with these scripts.

I liked the Skull ship, the triple light speed jump, and Kara Kara and Slay. Making her the female Han Solo was a nice touch, since it’s impossible to create another Han Solo in the Star Wars universe without it looking like you’re directly ripping off Han Solo. Kara Kara felt like her own person. And that was good. But man, I wish this story had more bite!

You know I worried, at first, that there would be no true screenwriting lessons to come out of this week. That the only things we’d be able to learn were Star Wars specific (a sexualized teenaged lesbian relationship at the core of a Star Wars film probably isn’t the best way to go). But now that I think about it, I realize that every writer is dealing with the exact same issues these Star Wars writers are dealing with.

Whatever genre you like to write in, that genre is your “Star Wars.” Just like that iconic film, your genre has done everything already. Just like these Star Wars writers can either write clones of their favorite Star Wars films or push the franchise into new territory, you can either write clones of your favorite genre films or push into new territory.

It isn’t easy to do, to “try.” It’s so much easier to fall back on what’s been done before because it doesn’t take any thinking on your part. But if you do go that extra mile and seek out those new ideas, and you do that consistently throughout your script, I guarantee you, you’re going to write something that readers and audiences remember.

Script link: Star Wars: The Admiral’s Vendetta

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: I leave this debate to all of you. Should you include adverbs in your writing? Some writers HATE them. Indeed, they can read clunky. But sometimes they feel like the only option. For example, here’s a line from “Vendetta:”

The Gunship laserfire sprays impotently into blackness.

Should the word “impotently” be here? Or does the sentence pack more punch without it? Or does the adverb add enough of a descriptive element to justify its existence? Weigh in in the comments section. I’m eager to get a consensus on this.

To keep Star Wars Week going, post: “Team Jedi” in the comments.

If you want me to move on, post: “Team Sith,” even though you probably don’t know what that means.

Should you be aspiring to write the next Cloud Atlas?

Should you be aspiring to write the next Cloud Atlas?

Today I want to pose a question to you that’s had me stumped for awhile.

What is the difference between BAD non-traditional writing and GOOD non-traditional writing?

I’m asking this question because I meet so many writers who insist on defying convention. I read their scripts and I say, “I don’t see a focused story here. I don’t see you setting up your characters correctly. I don’t see your story starting soon enough. I don’t see you adding conflict or suspense or any of the things that traditionally keep a reader interested.” And their response to me is always, “Well I don’t want to do it like that. That’s how Hollywood does it and I don’t like Hollywood movies. I want to do it differently.”

My gut reaction is to groan, but then I realize that they have a point. There isn’t just “one way” to do something. There are lots of ways. And if I tell these writers, “No, don’t do it that way,” aren’t I stifling their creativity? Aren’t I potentially preventing a new voice from emerging? If I was Captain of Hollywood, True Detective would’ve never been made. Yet there are a lot of people who love True Detective, and that’s definitely a show that “does it differently.”

Here’s the problem though. 99% of the time I let these writers roam free, they come back with a hodge-podge of ideas, sequences, and characters in search of a script. It’s like walking into a Category 5 Screenplay Storm. Anyone who’s been tasked with reading amateur scripts where the writers ignore all storytelling convention knows what I’m talking about.

Yet these writers continue to drum up compelling arguments to defend their approach. They say, “Well I don’t want to write Transformers, or Grown-Ups, or Identity Thief, or Olympus Has Fallen. Those scripts follow all the rules and they suck.” Hmm, I think. Can’t argue with that. And yet I can’t seem to convey to them that even Hollywood’s vanilla is better than their chocolate without getting a funny look or a black eye.

Maybe we can solve this by moving away from the amateur world and into the professional one. Because in this venue, writers are having the same battle. They all want to write something challenging and unique, a convention-defying opus that will win them an Oscar. All else being equal, no one wants to write Battleship. And they seem to have hard-core cinemagoers on their side. You need look no further than the Scriptshadow comment thread to see Grendl preaching this every day – break away from convention, ignore the rules, create something original!

But let me offer you the flip side of this argument. It’s only two words long.

Cloud Atlas

Here’s a book that was adapted by and then directed by the Wachowskis (and Tom Tykwer), three of the more visionary directors in Hollywood. The result was one of the most beautiful movies of the last decade. And one of the most unfocused unsatisfying stories of the year. I’m not going to say the film didn’t have fans. But by and large, it was a failure, making only 30 million domestic. A documentary about chimpanzees made more money that year.

I bring the film up because this is the kind of thing you’re advocating when you say, “Fuck convention and write whatever you want.” You have three of the stronger talents in the business writing six narratives spanning six different time periods, with no clear connection. Set one of those time periods a thousand years in the future. Have the main character followed around by a homeless looking Leprechaun creature who spouts out indecipherable ramblings. I mean come on! There isn’t a single audience member who’s going to respond to that. It’s too weird!

And I can hear you from here. You’re saying, “Well I’d rather Hollywood produce ten failures like Cloud Atlases than one “hit” Iron Man 3.” No you wouldn’t. You wouldn’t. I dare you to sit down and try and watch Cloud Atlas’s three hour running time and not start checking your e-mail by the halfway point. I thought Iron Man 3 was pretty bad. But at least it was trying to entertain me.

My lack of enjoyment not-withstanding, the point is, two popular writers were given free rein to go crazy with a huge budget and created a piece of doo-doo. Which begs the question, is this what we want all the time? Julie Delpy written movies? Shane Carruth written movies? Another “Somewhere” from Sophia Coppola? Steve Soderbergh busting out films like “Bubble” every year?

It sounds fun in theory. Yeah! Give those guys gobs of money and let them do whatever they want. But what are the actual consequences? The consequences are film geeks getting to masturbate online about 10 minute tracking shots. But that’s where the benefits end. There would be no movie business because attendance would be down 90%. And the thing is, what you’re asking for is already here! These movies have already happened. You’ve just never heard of them because they were so bad.

Does a movie that promises to aggressively subvert the romantic comedy genre sound intriguing? Sure. But watch “I Give It A Year” and tell me you don’t want to kill yourself by the end of the first act. Diablo Cody won an Oscar. Let’s let her go wild on the page and see what happens. It happened, with a movie called “Paradise,” which I’m pretty sure is still waiting for its first customer. Francis Ford Coppola was given free rein on his last film. What did he come up with? Twixt. I’m guessing you didn’t rush over to Fandango to find the opening day showtimes for that one.

Now you may be saying, “Yeah, but I don’t like the sound of any of those movies, Carson. So of course I’m not going to see them.” That’s the problem. Millions of other people feel the same way. And if no one’s going to see these “fuck convention – I’ll write what I want” movies, then there won’t be a movie industry anymore.

On the flip side, there are definitely screenplays that have defied convention and turned out great. Pulp Fiction, Slumdog Millionaire, American Beauty. More recently, some might say American Hustle and Her. Which is why answering this question is so difficult. What makes one unconventional script good and another terrible?

I’ll give you an example from both sides. What makes the intense dramatic unconventional Short Term 12 good while the equally intense dramatic unconventional Labor Day is terrible? I suppose we can break down each script point by point, but I’m looking at the bigger picture. How do writers not bound by rules keep away from the bad and write something good? Do they just follow their heart? Should writing contain no form whatsoever other than the stream-of-consciousness rolling off the writer’s fingertips? I mean we can’t really be advocating this, right? There’s got to be a plan.

Ah-haaaaa. I believe that may be the clue we’ve been looking for.

If we’re going to do something as radical as defy convention, it only makes sense that we have a plan. Now that I think about it, the successful “unconventional” screenwriters I’ve spoken with always knew why they did what they did. They understood their unorthodox choices and made them for a reason. The people whose unconventional scripts aren’t so good are those who can’t answer any questions about their choices. They seem tripped up when you ask them even the simplest question, like “why did you choose this plot point here?” or “why did Character A do that?” They never had a plan, which is why their scripts tend to feel so aimless and frustrating.

So what I’d say to everyone planning on writing that next great unconventional screenplay, learn everything you can about this craft and then have a plan when you write. It doesn’t have to be everybody else’s plan. It just has to be yours. And know why you’re doing shit. The more control you have over your choices, the more logical your script is going to be, and the easier it’s going to be for your reader to digest. If you think that advice is for wimps and you want to fly by the seat of your pants, that’s fine. But don’t be surprised if you leave a lot of confused readers in your wake.

What about you guys? What do you think the key is to writing an unconventional screenplay?

Genre: TV Pilot – Sci-fi/Thriller/Drama

Premise: In the near future, a robot is accused of murder for the first time ever. A young defense attorney must find out how to defend him, despite there being no precedent for the case.

About: Tin Man was written by Ehren Kruger, one of the biggest screenwriting names in town, as he’s written almost all of the Transformers movies. He also penned horror favorite, The Ring, and busted onto the scene with the awesome thriller, Arlington Road. While the draft I read of Tin Man is listed as a traditional pilot, I’m seeing on IMDB that Tin Man will be more of a TV movie. Not sure what that means, but this seems to be part of a new protective network trend designed to take risks without admitting failure. If the show doesn’t do well, they just say it was a one-off. If it does do well, they turn it into a series. Tin Man will air on NBC this year.

Writer: Ehren Kruger

Details: 54 pages – undated

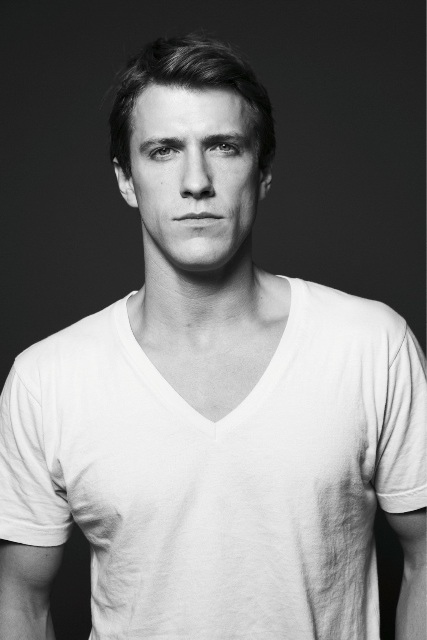

Up-and-coming actor Patrick Heusinger will play the Tin Man!

Up-and-coming actor Patrick Heusinger will play the Tin Man!

Man, I had to work a long time and weed through a TON of pilots to find one that wasn’t a procedural. I saw everything from a detective who’s going blind and uses his other senses to solve crimes, to a lawyer who’s secretly an alien. Procedurals are the reason I’ve been uninterested in TV for so long. I never understood why you’d watch a show whose story didn’t evolve in subsequent episodes.

It wasn’t until serialized shows started making a big push after Lost that TV became interesting. But Hollywood loves its procedural television and doesn’t want to move away from it anytime soon. There seems to be two reasons for that. One, procedural television is a lot easier to write for on a long-term basis. Just give a lawyer a case to argue, a doctor a patient to save, or a detective a murder to solve, and you can write episode after episode after episode. The engine (goal) that drives each episode is built right into the format!

Two, it’s much easier for procedural shows to pick up new viewers. Understanding the show doesn’t require you to know what happened five episodes ago, whereas in a serialized show, like Breaking Bad, that’s not the case. We need to know that Walter killed that crazy ass drug dealer to understand why these two drug kingpins are after him this week.

This is, of course, changing. If you start hearing about a good serialized show, you can always “binge watch” it on Netflix and catch up to the series in the process. And you have to remember, we didn’t used to have huge DVD sets of an entire series, or the entire show a click away on Amazon or Itunes. So even when a show is over, it can still make a lot of money from old viewers as well as new ones. In other words, these days, TV is more receptive to the serialized format than ever.

Which is a good thing. Because the sooner we can get away from networks putting procedurals about cops in wheelchairs on television (Remember Ironside???) the better.

With that said, this still doesn’t solve that other issue: how to WRITE these serialized shows. When you write a serialized show, you have to come up with a new story engine EVERY SINGLE EPISODE. Think about how hard that is. With Grey’s Anatomy, all they had to do was say, “We just got a man in the East Wing who’s showing signs of pregnancy,” and that episode is taken care of. Coming up with original plot lines time and time again for shows like Lost and Breaking Bad is a lot more challenging than it looks.

Anyway, that’s a rather long rant that doesn’t have a whole lot to do with today’s pilot, so why don’t we switch gears and get to that.

Tim Man takes place in the near future and follows a robot named Adam Sentry (who looks 30 years old in human years). Adam is the creation of trillionaire (yes, with a “t”) Charles Vale, who owns a huge robotics company. Adam is Vale’s de facto robot Butler, and takes care of every aspect of his life, which is relevant, because Vale is sick and going to die soon.

Turns out it isn’t the cancer that gets him though. Vale is murdered in his home one evening. And who’s the only one in the house with him at the time? That’s right. Adam. So Adam is taken to the police station and read his Miranda Rights. Which sounded like a good idea at the time until the police realize that they can’t read Miranda Rights to a bunch of bolts and wires. That would imply he’s human.

And thus the United States Court System must figure out how to proceed with the first ever robot accused of murder. Do they try him? Do they turn him into scrap metal? There’s all sorts of implications here, since if you try a robot, that implies robots are equal to humans, and then you start giving them rights, and pretty soon they’re running the world and then you have Terminators and then you have the Matrix.

Adam surprisingly asks for a dying breed to defend him, a HUMAN defense lawyer. Katie Piper sees this as an opportunity to bust out of being a glorified secretary and takes the job. But she learns the hard way that the Vale corporation doesn’t want Adam anywhere near a trial. They want him terminated. So when (spoiler) they try to kill him, Adam has no other choice but to resist everything that was programmed into him, and go on the run. He knows that his one shot at not being shut down, is finding out who killed Charles Vale, and why.

All you can really ask for from a show/script/movie is that the writer execute the idea in a way that isn’t obvious. I mean, you still want them to fulfill the promise of the premise. People who bought tickets for The Terminator because they heard it was about a killer cyborg want to see scenes where a cyborg kills people. But on the whole, if an idea is executed exactly as expected, it’s boring.

I don’t know about you, but I want to be surprised. I want the writer to be ahead of me. And Tin Man unravels slightly differently than I expected, which was refreshing. I think I was expecting a straight-forward boring delivery about the increasingly frequent debate (in sci-fi screenwriting) of whether robots should be given equal status to humans.

We get a little of that, but we also get this plucky human defense lawyer, a “dying breed,” who’s using this opportunity less as a noble cause and more as a way to advance her career. When that happened and I realized I wasn’t going to be preached to, I was on board.

And I liked the implication that Adam was holding a bunch of proprietary information, since he was Charles Vale’s personal robot, and what that could mean for the company if he went to trial and was forced to divulge those secrets. And therefore them wanting to kill him before he made it to trial. All of a sudden, there were a few more layers to the story than I expected. The stakes were higher than just “should we try robots?”

And the pilot didn’t end how I expected it to either. I assumed this was the beginning of a drawn out court case that would last half the first season. But at the end (spoiler), Adam escapes and we’re essentially introduced to a future version of The Fugitive. I was surprised at how closely this mimicked that premise, but it’s a recipe that definitely works, and thank god it keeps us away from procedural territory.

I don’t know if I had any problems with the script other than, maybe, it doesn’t feel ground-breaking enough? It feels a little too familiar? Robots seem to be the new craze in TV. We have Almost Human. Extant, coming up on CBS, and I’m sure at least a couple of series on SyFy.

This idea of people mimicking robots… I don’t know how else to put it but it feels like an easy way to squeeze a high concept into a small budget. Which is fine. Budget-wise, it’s a smart move. But I feel that audiences are becoming hip to this approach, which is why shows like Almost Human reek of cheapness. Occasionally showing the metal skeleton other underneath the skin after the robot gets cut—we’re kind of tired of that, seeing as we saw it all the way back in The Terminator.

I suppose it’s all in how its shot, the vision and what the production value is, but I need more than just “robots in human skin” these days to get excited about a series.

With that said, I think Kruger is a good writer. You may not agree when you see those Transformers credits, but the impression I get there is that he’s writing with 50 heads over his shoulder. In this case, with Tin Man, I see something solid. It’s not spectacular, but it’s a good pilot.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: You don’t HAVE to write a strict “serialized” show or a strict “procedural” show. You can heavily serialize something (like Lost) or you can write a procedural with serialized elements, like The X-Files. The X-Files had plenty of standalone procedural shows, but then would have shows that solely dealt with the mythology. So don’t feel like you have to go only one way or only the other when making the procedural/serial choice.

Inception’s first act is pretty awesome.

Inception’s first act is pretty awesome.

It surprises me that people have trouble with the first act because it’s easily the most self-explanatory act there is. Introduce your hero, then your concept, then send your hero out on his/her journey. But I suppose I’m speaking as someone who’s dissected a lot of first acts. And actually, when I really start thinking about it, it does get tricky in places. The most challenging part is probably packing a ton of information into such a small space. So that’s something I’ll be addressing. Also, I’ve decided to include my second and third act articles afterwards so that this can act as a template for your entire script. Hopefully, this gives you something to focus on the next time you bust open Final Draft. Let’s begin!

INTRODUCE YOUR HERO (page 1)

Preferably, the first scene will introduce your hero. This is a very important scene because beyond just introducing your hero, you’re introducing yourself as a writer. A reader will be making quick judgments about you on everything from if you know how to write, if you know how to craft a scene, and what level you’re at as a screenwriter. So of all the scenes in your script, this is the one that you’ll probably want to spend the most time on. It’s also extremely important to DEFINE your hero with this scene. Whatever the biggest strength and/or weakness of your hero, try to construct a scene that shows us that. Finally, try to convey who your hero is THROUGH THEIR ACTIONS (as opposed to telling us). If your hero is afraid to take initiative, give them the option in the scene to take initiative, then show them failing to do so. A great opening scene that shows all of these things is the opening of Raiders of the Lost Ark.

SET UP YOUR HERO’S WORLD (pages 3- 15)

The next few scenes will consist of showing us your hero’s world. This might show him/her at work, with friends, with family, going about their daily life. This is also the section where you set up most of the key characters in the script. In addition to setting up their world, you want to hit on the fact that something’s missing in their life, something the hero might not even be aware of. Maybe they’re missing a companion (Lars and the Real Girl). Maybe they’re putting work over family (George Clooney in Up in the Air). Maybe they’re allowing others to push them around (American Beauty). It’s important NOT TO REPEAT scenes in this section. Keep it between 2-5 scenes because between pages 12-15, you’re going to want to introduce the inciting incident.

INCITING INCIDENT (pages 12-15)

Introducing the inciting incident is just a fancy way of saying, “Introducing a problem that rocks your protagonist’s world.” This problem makes its way into your hero’s life, forcing them to act. Maybe their plane crashes (The Grey), they get someone pregnant (Knocked Up), or their daughter gets kidnapped (Taken). Now your hero is forced to make a decision. Do they act or not? — It should be noted that sometimes the inciting incident will arrive immediately, as in, on the very first page. For example, if a character wakes up with amnesia (Saw, The Bourne Identity) or something traumatic happens in the opening scene (Garden State – his father dies), the hero is encountering their inciting incident (their problem) immediately.

HELL NO, I AIN’T GOIN (aka “Refusal of the Call”) (roughly pages 16-25)

The “Hell No I ain’t goin” section occurs right after the inciting incident and basically amounts to your character saying (you guessed it), “I’m not goin anywhere.” The reason you see this in a lot of scripts is because it’s a very human response. Humans HATE change. They hate facing their fears. The problem that arises from the inciting incident is usually a manifestation of their deepest fear. So of course they’re going to reject it. Neo says no to scaling a building for Morpheus and gives in to the baddies instead. This sequence can last one or several scenes. It’ll show your hero trying to go back to what they know.

OFF TO THE JOURNEY (page 25)

When your character decides to go off on their journey (and hence into the second act), it’s usually because they realize this problem isn’t going away unless they deal with it. So in order to erase this eternal snowfall, Anna from Frozen must go off, find her sister and ask her to end it. This is where the big “G” in “GSU” comes from. As your hero steps into that second act, it begins the pursuit of their goal, which is to solve the problem.

GRAB US IMMEDIATELY

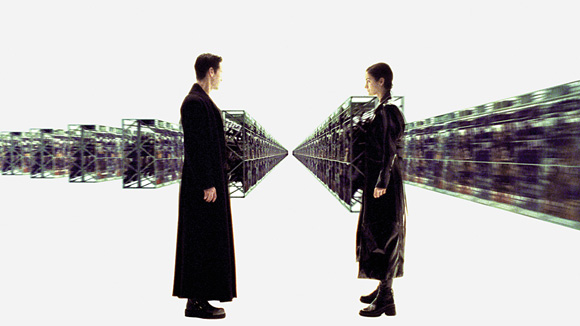

Now that you know the basic structure, there’s a few other things you want to focus on in the first act. The first of those things? Don’t fuck around! Readers are impatient as hell, expecting you to be bad writer (since you’re an amateur) and judging you immediately. So try and lure them in with a kick-ass scene right away and don’t let them off the hook (each successive scene should be equally as page-turning). This doesn’t mean start with an action scene (although you can). It could mean a clever reversal scene or an unexpected twist in the middle of the scene. Pose a mystery. A murder. Show us something that’s impossible (people jumping across roofs – The Matrix). Use your head and just make us want to keep turning the pages even if our fire alarm is going off in the other room. Achieving this tall order WHILE doing all the other shit I listed above (set up your hero and his flaw), is what makes writing so tricky.

MAKE IT MOVE

It’s important that the first act move. Bad writers like to DRILL things into the reader’s head over and over and over again. For example, if they want to show how lonely their hero is, they’ll show like FIVE SCENES of them being lonely. And guess what us readers are doing? We’re already skimming. Typically, a reader picks things up quickly if you display/convey information properly. Show that your hero is bad with women in the first scene, we’ll know they’re bad with women. There are some things you want to repeat in a script (a character’s flaw, for example) but you want to slip that into scenes that are entertaining and necessary for the story, not carve out entire scenes that are ONLY reiterating something we already know. This is one of the BIGGEST tells for an amateur writer, so avoid it at all costs!

ENTERTAIN US WHILE SETTING US UP

You’re setting up a lot of stuff in your first act. You’re setting up your main character’s everyday life, their flaws, the love interest (possibly), secondary characters, the inciting incident, setups for later payoffs. For that reason, a first act can quickly turn into an information dump. That’s fine for a first draft. But as you rewrite, you’ll want to smooth all this information over, hide it even, and focus on ENTERTAINING US. Nobody’s going to pat you on your back for doing everything I’ve listed above. That stuff is EXPECTED. They’re only going to pat you on the back if your first act is entertaining. Think of it like this. Nobody wants to know how a roller coaster works. They just want to ride on it.

EVERY SCRIPT IS UNIQUE

One of the hardest things about writing is that every story presents unique challenges that force you to improvise. Nobody’s going to be able to follow the formula I laid out to a “T.” You’re going to have to adjust, improvise, invent. That shouldn’t be scary. You’re artists. That’s what you do. Just to give you a few examples, Luke Skywalker is not introduced in the beginning of Star Wars. Marty McFly doesn’t choose to go on his adventure. He’s thrust into it unexpectedly (when his car jumps back to the past). Some films, like Crash, have multiple characters that need to be set up. This requires you to set up a dozen little mini-stories (for each character) as opposed to one big one. Some scripts start with a teaser (Jurassic Park) or a preamble (Inception). The point is, don’t pigeonhole yourself into the above unless you have a very straightforward plot (like Taken, Rocky, or Gravity). Otherwise, be adaptable. Understand where your story is resisting structure, and be open to trying something different.

IN SUMMARY

That’s probably the scariest thing about writing, is tackling the unknown. So what do you do if you come upon these unique challenges? What do you do with your first act, for example, if the inciting incident happens right away, as it does in The Bourne Identity? Do you still break into the second act on page 25? Well, I know the answer to that question as well as some other tricky scenarios, but they’d require their own article (short answer – you break into the second act a little earlier, around page 20). What I’ll say is, this is one of the big things that separates the pros from the amateurs. The pro, because he’s written a lot more, has encountered more problematic scenarios and had more experience trying to solve them. The only way to catch up to them is to keep writing a lot (not just one script, but many, since each script creates its own set of challenges) and figure out these answers for yourselves. The good news is, with this article, you have a template to start from. And remember, when all else fails, storytelling boils down to one simple coda: A hero encounters a problem and must find a solution. That’s true for a story. It’s true for individual characters. It’s true for subplots. It’s true for individual scenes. If you follow that layout, you should do fine. And if you want to get into more detail about this stuff, check out my book, which is embarrassingly cheap at just $4.99 on Amazon! ☺

THE SECOND ACT!

Character Development

One of the reasons the first act tends to be easy is because it’s clear what you have to set up. If your movie is about finding the Ark, then you set up who your main character is, what the Ark is, and why he wants to get it. The second act isn’t as clear. I mean sure, you know your hero has to go off in pursuit of his goal, but that can get boring if that’s the ONLY thing he’s doing. Enter character development, which really boils down to one thing: your hero having a flaw and having that flaw get in the way of him achieving his goal. This is actually one of the more enjoyable aspects of writing. Because whatever specific goal you’ve given your protag, you simply give them a flaw that makes achieving that goal really hard. In The Matrix, Neo’s goal is to find out if he’s “The One.” The problem is, he doesn’t believe in himself (his flaw). So there are numerous times throughout the script where that doubt is tested (jumping between buildings, fighting Morpheus, fighting Agent Smith in the subway). Sometimes your character will be victorious against their flaw, more often they’ll fail, but the choices they make and their actions in relation to this flaw are what begin to shape (or “develop”) that character in the reader’s eyes. You can develop your character in other ways (via backstory or everyday choices and actions), but developing them in relation to their flaw is usually the most compelling part for a reader to read.

Relationship Development

This one doesn’t get talked about as much but it’s just as important as character development. In fact, the two often go hand in hand. But it needs its own section because, really, when you get into the second act, it’s about your characters interacting with one another. You can cram all the plot you want into your second act and it won’t work unless we’re invested in your characters, and typically the only way we’re going to be invested in your characters is if there’s something unresolved between them that we want resolved. Take last year’s highest grossing film, The Hunger Games. Katniss has unresolved relationships with both Peeta (are they friends? Are they more?) and Gale (her guy back home – will she ever be able to be with him?). We keep reading/watching through that second act because we want to know what’s going to happen in those relationships. If, by contrast, a relationship has no unknowns, nothing to resolve, why would we care about it? This is why relationship development is so important. Each relationship is like an unresolved mini-story that we want to get to the end of.

Secondary Character Exploration

With your second act being so big, it allows you to spend a little extra time on characters besides your hero. Oftentimes, this is by necessity. A certain character may not even be introduced until the second act, so you have no choice but to explore them there. Take the current film that’s storming the box office right now, Frozen. In it, the love interest, Kristoff, isn’t introduced until Anna has gone off on her journey. Therefore, we need to spend some time getting to know the guy, which includes getting to know what his job is, along with who his friends and family are (the trolls). Much like you’ll explore your primary character’s flaw, you can explore your secondary characters’ flaws as well, just not as extensively, since you don’t want them to overshadow your main character.

Conflict

The second act is nicknamed the “Conflict Act” so this one’s especially important. Essentially, you’re looking to create conflict in as many scenarios as possible. If you’re writing a haunted house script and a character walks into a room, is there a strange noise coming from somewhere in that room that our character must look into? That’s conflict. If you’re writing a war film and your hero wants to go on a mission to save his buddy, but the general tells him he can’t spare any men and won’t help him, that’s conflict. If your hero is trying to win the Hunger Games, are there two-dozen people trying to stop her? That’s conflict. If your hero is trying to get her life back together (Blue Jasmine) does she have to shack up with a sister who she screwed over earlier in life? That’s conflict. Here’s the thing, one of the most boring types of scripts to read are those where everything is REALLY EASY for the protagonist. They just waltz through the second act barely encountering conflict. The second act should be the opposite of that. You should be packing in conflict every chance you get.

Obstacles

Obstacles are a specific form of conflict and one of your best friends in the second act because they’re an easy way to both infuse conflict, as well as change up the story a little. The thing with the second act is that you never want your reader/audience getting too comfortable. If we go along for too long and nothing unexpected happens, we get bored. So you use obstacles to throw off your characters AND your audience. It should also be noted that you can’t create obstacles if your protagonist ISN’T PURSUING A GOAL. How do you place something in the way of your protagonist if they’re not trying to achieve something? You should mix up obstacles. Some should be big, some should be small. The best obstacles throw your protagonists’ plans into disarray and have the audience going, “Oh shit! What are they going to do now???” Star Wars is famous for one of these obstacles. Our heroes’ goal is to get the Death Star plans to Alderaan. But when they get to the planet, it’s been blown up by the Death Star! Talk about an obstacle. NOW WHAT DO THEY DO??

Push-Pull

There should always be some push-pull in your second act. What I mean by that is your characters should be both MAKING THINGS HAPPEN (push) and HAVING THINGS HAPPEN TO THEM (pull). If you only go one way or the other, your story starts to feel predictable. Which is a recipe for boredom. Readers love it when they’re unsure about what’s going to happen, so you use push-pull to keep them off-balance. Take the example I just used above. Han, Luke and Obi-Wan have gotten to Alderaan only to find that the planet’s been blown up. Now at this point in the movie, there’s been a lot of push. Our characters have been actively trying to get these Death Star plans to Alderaan. To have yet another “push” (“Hey, let’s go to this nearby moon I know of and regroup”) would continue the “push” and feel monotnous. So instead, the screenplay pulls, in this case LITERALLY, as the Death Star pulls them in. Now, instead of making their own way (“pushing”), something is happening TO them (“pull”). Another way to look at it is, sometimes your characters should be acting on the story, and sometimes your story should be acting on the characters. Use the push-pull method to keep the reader off-balance.

Escalation Nation

The second act is where you escalate the story. This should be simple if you follow the Scriptshadow method of writing (GSU). Escalation simply means “upping the stakes.” And you should be doing that every 15 pages or so. We should be getting the feeling that your main character is getting into this situation SO DEEP that it’s becoming harder and harder to get out, and that more and more is on the line if he doesn’t figure things out. If you don’t escalate, your entire second act will feel flat. Let me give you an example. In Back to the Future, Marty gets stuck in the past. That’s a good place to put a character. We’re wondering how the hell he’s going to get out of this predicament and back to the present. But if that’s ALL he needs to do for 60 pages, we’re going to get bored. The escalation comes when he finds out that he’s accidentally made his mom fall in love with him instead of his dad. Therefore, it’s not only about getting back to the present, it’s about getting his parents to fall in love again so he’ll exist! That’s escalation. Preferably, you’ll escalate the plot throughout the 2nd act, anywhere from 2-4 times.

Twist n’ Surprise

Finally, you have to use your second act to surprise your reader. 60 pages is a long time for a reader not to be shocked, caught off guard, or surprised. I personally love an unexpected plot point or character reveal. To use Frozen, again, as an example, (spoiler) we find out around the midpoint that Hans (the prince that Anna falls in love with initially) is actually a bad guy. What you must always remember is that screenwriting is a dance of expectation. The reader is constantly believing the script is going to go this way (typically the way all the scripts he reads go). Your job is to keep a barometer on that and take the script another way. Twists and surprises are your primary weapons against expectation, so you’ll definitely want to use them in your second act.

IN SUMMARY

In summary, the second act is hard. But if you have a structural road-map for your story (you know where your characters are going and what they’re going after), then these tools should fill in the rest. Hope they were helpful and good luck implementing them in your latest script. May you be the next giant Hollywood spec sale! :)

THE THIRD ACT!

THE GOAL

Without question, your third act is going to be a billion times easier to write if your main character is pursuing a goal, preferably since the beginning of the film. “John McClane must save his wife from terrorists” makes for a much easier-to-write ending than “John McClane tries to figure out his life” because we, the writer, know exactly how to construct the finale. John McClane is either going to save his wife or he’s going to fail to save his wife. Either way, we have an ending. What’s the ending for “John McClane tries to figure out his life?” It’s hard to know because that scenario is so open-ended. The less clear your main character’s objective (goal) is in the story, the harder it will be to write a third act. Because how do you resolve something if it’s unclear what your hero is trying to resolve?

THE LOWEST POINT

To write a third act, you have to know where your main character is when he goes into the act. While this isn’t a hard and fast rule, typically, putting your hero at his lowest point at the end of act two is a great place to segue into the third act. In other words, it should appear at this point in the story that your main character has FAILED AT HIS/HER GOAL (Once Sandra Bullock gets to the Chinese module in GRAVITY, that’s it. Air is running out. She doesn’t understand the system. There are no other options). Either that, or something really devastating should shake your hero (i.e. his best friend and mentor dies – Obi-Wan in Star Wars). The point is, it should feel like things are really really down. When you do this, the audience responds with, “Oh no! But this can’t be. I don’t want our hero to give up. They have to keep trying. Keep trying, hero!” Which is exactly where you want them!

REGROUP

The beginning of the third act (anywhere from 1-4 scenes) becomes the “Regroup” phase. This phase often has to deal with your hero’s flaw, which is why it works so well in comedies or romantic comedies, where flaws are so dominant . If your hero is selfish, he might reflect on all the people he was selfish to, apologize, and move forward. But if this is an action film, it might simply mean talking through the terrible “lowest point” thing that just happened (Luke discussing the death of Obi-Wan with Han) and then getting back to it. Your hero was just at the lowest point in his/her life. Obviously, he needs a couple of scenes to regroup.

THE PLAN

Assuming we’re still talking about a hero with a goal, now that they’ve regrouped, they tend to have that “realization” where they’re going to give this goal one last shot. This, of course, necessitates a plan. We see this in romantic comedies all the time, where the main character plans some elaborate surprise for the girl, or figures out a way to crash the big party or big wedding. In action films, it’s a little more technical. The character has to come up with a plan to save the girl, or take down the villain, or both. In The Matrix, Neo needs to save Morpheus. He tells Trinity the plan, they go outfit themselves with guns from the Matrix White-Verse, and they go in there to get Morpheus.

THE CLIMAX SCENE

This should be the most important scene in your entire script. It’s where the hero takes on the bad guy or tries to get the girl back. You should try and make this scene big and original. Give us a take on it that we’ve never seen in movies before. Will that be hard? Of course. But if you’re rehashing your CLIMAX SCENE of all scenes?? The biggest and most important scene in the entire screenplay? You might as well give up screenwriting right now. If there is any scene you need to challenge yourself on, that you need to ask, “Is this the best I can possibly do for this scene?” and honestly answer yes? This is that scene!

THE LOWER THAN LOWEST POINT

During the climax scene, there should be one last moment where it looks like your hero has failed, that the villain has defeated him (or the girl says no to him). Let’s be real. What you’re really doing here is you’re fucking with your audience. You’re making them go, “Nooooooo! But I thought they were going to get together!” This is a GOOD THING. You want to fuck with your audience in the final act. Make them think their hero has failed. I mean, Neo actually DIES in the final battle in The Matrix. He dies! So yeah, you can go really low with this “true lowest point.” If the final battle or confrontational or “get-the-girl” moment is too easy for our hero, we’ll be bored. We want to see him have to work for it. That’s what makes it so rewarding when he finally succeeds!

FLAWS

Remember that in addition to all this external stuff that’s going on in the third act (getting the girl, killing the bad guy, stopping the asteroid from hitting earth), your protagonist should be dealing with something on an internal level as well. A character battling their biggest flaw on the biggest stage is usually what pulls audiences and readers in on an emotional level, so it’s highly advisable that you do this. Of course, this means establishing the flaw all the way back in Act 1. If you’ve done that, then try to tie the big external goal into your character’s internal flaw. So Neo’s flaw is that he doesn’t believe in himself. The only way he’ll be able to defeat the villain, then, is to achieve this belief. Sandra Bullock’s flaw in Gravity is that she doesn’t have the true will to live ever since her daughter died. She must find that will in the Chinese shuttle module if she’s going to survive. If you do this really well, you can have your main character overcome his flaw, but fail at his objective, and still leave the audience happy (Rocky).

PAYOFFS

Remember that the third act should be Payoff Haven. You should set up a half a dozen things ahead of time that should all get some payin’ off here in the finale. The best payoffs are wrapped into that final climactic scene. I mean who doesn’t sh*t their pants when Warden Norton (Shawshank spoiler) takes down that poster from the wall in Andy Dufresne’s cell? But really, the entire third act should be about payoffs, since almost by definition, your first two acts are setups.

OBSTACLES AND CONFLICT

A mistake a lot of beginner writers make is they make the third act too easy for their heroes. The third act should be LOADED with obstacles and conflict, things getting in the way of your hero achieving his/her goal. Maybe they get caught (Raiders), maybe they die (The Matrix), maybe the shuttle module sinks when it finally gets back to earth and your heroine is in danger of drowning (Gravity). The closer you get to the climax, the thicker you should lay on the obstacles, and then when the climactic scene comes, make it REALLY REALLY hard on them. Make them have to earn it!

NON-TRADITIONAL THIRD ACTS (CHARACTER PIECES)

So what happens if you don’t have that clear goal for your third act? Chances are, you’re writing a character piece. While this could probably benefit from an entire article of its own, basically, character pieces still have goals that must be met, they’re just either unknown to the hero or relationship-related. Character pieces are first and foremost about characters overcoming their flaws. So if your hero is selfish, your final act should be built around a high-stakes scenario where that flaw will be challenged. Also, character piece third acts are about resolving relationship issues. If two characters have a complicated past stemming from some problem they both haven’t been able to get over, the final act should have them face this issue once and for all. Often times, these two areas will overlap. In other words, maybe the issue these two characters have always had is that he’s always put his own needs over the needs of the family. The final climactic scene then, has him deciding whether to go off to some huge opportunity or stay here and takes care of the family. The scenario then resolves the character flaw and the relationship problem in one fell swoop! (note: Preferably, you are doing this in goal-oriented movies as well)

IN SUMMARY

While that’s certainly not everything, it’s most of what you need to know. But I admit, while all of this stuff is fun to talk about in a vacuum, it becomes a lot trickier when you’re trying to apply it to your own screenplay. That’s because, as I stated at the beginning, each script is unique. Indiana Jones is tied up for the big climax of Raiders. That’s such a weird third act choice. In Back To The Future, George McFly’s flaw is way more important than our hero, Marty McFly’s, flaw. When is the “lowest point before the third act” in Star Wars? Is it when they’re in the Trash Compactor about to be turned into Star Wars peanut butter? Or is at after they escape the Death Star? I think that’s debatable. John McClane never formulates a plan to take on Hanz in the climax. He just ends up there. The point is, when you get into your third act, you have to be flexible. Use the above as a guide, but don’t follow it exactly. A lot of times, what makes a third act memorable is its imperfections, because it’s its imperfections that make it unpredictable. If you have any third act tips of your own, please leave them in the comments section. Wouldn’t mind learning a few more things about this challenging act myself!

Gone Girl had a disappointing final act. So Fincher had author Flynn rewrite it for the movie. Will it save the film?

Gone Girl had a disappointing final act. So Fincher had author Flynn rewrite it for the movie. Will it save the film?

In the five years since this site began, it’s hard to believe that I STILL haven’t written an article about the third act. I think it’s because the third act is kinda scary. It’s easy to set up a story. The middle act is tough, however I’ve written a couple of articles demystifying the process. But with final acts, it feels like every one is a little different. They’re sort of like their own little organisms, evolving and changing in indefinably unique ways, packed with previously established variables that are constantly fighting against one another, and it’s hard to bring all of that together in a streamlined package.

Blake Snyder does a really good job breaking down the third act, and his methods are a good place to start, but what I’ve found is that his approach mostly applies to comedies and romantic comedies, where the audience is aware of the exaggerated structure of the moment (hero loses the girl, is at his lowest point) but doesn’t mind. They come to see these movies because they like laughing and seeing the guy get the girl, so they don’t need some genius plot point to keep them invested.

With that said, I think it’s a good idea to have a baseline approach to your third act. It’s the same thing as if you’re building a house. You want to get the blueprints in order. But you still need to keep the option open of adding a breakfast nook over here, or moving the kitchen over to the other side of the main room. So here’s how a prototypical third act should be structured. It doesn’t mean that your act should be structured the same way. It just means it’s a starting point.

THE GOAL

Without question, your third act is going to be a billion times easier to write if your main character is pursuing a goal, preferably since the beginning of the film. “John McClane must save his wife from terrorists” makes for a much easier-to-write ending than “John McClane tries to figure out his life” because we, the writer, know exactly how to construct the finale. John McClane is either going to save his wife or he’s going to fail to save his wife. Either way, we have an ending. What’s the ending for “John McClane tries to figure out his life?” It’s hard to know because that scenario is so open-ended. The less clear your main character’s objective (goal) is in the story, the harder it will be to write a third act. Because how do you resolve something if it’s unclear what your hero is trying to resolve?

THE LOWEST POINT

To write a third act, you have to know where your main character is when he goes into the act. While this isn’t a hard and fast rule, typically, putting your hero at his lowest point at the end of act two is a great place to segue into the third act. In other words, it should appear at this point in the story that your main character has FAILED AT HIS/HER GOAL (Once Sandra Bullock gets to the Chinese module in GRAVITY, that’s it. Air is running out. She doesn’t understand the system. There are no other options). Either that, or something really devastating should shake your hero (i.e. his best friend and mentor dies – Obi-Wan in Star Wars). The point is, it should feel like things are really really down. When you do this, the audience responds with, “Oh no! But this can’t be. I don’t want our hero to give up. They have to keep trying. Keep trying, hero!” Which is exactly where you want them!

REGROUP

The beginning of the third act (anywhere from 1-4 scenes) becomes the “Regroup” phase. This phase often has to deal with your hero’s flaw, which is why it works so well in comedies or romantic comedies, where flaws are so dominant . If your hero is selfish, he might reflect on all the people he was selfish to, apologize, and move forward. But if this is an action film, it might simply mean talking through the terrible “lowest point” thing that just happened (Luke discussing the death of Obi-Wan with Han) and then getting back to it. Your hero was just at the lowest point in his/her life. Obviously, he needs a couple of scenes to regroup.

THE PLAN

Assuming we’re still talking about a hero with a goal, now that they’ve regrouped, they tend to have that “realization” where they’re going to give this goal one last shot. This, of course, necessitates a plan. We see this in romantic comedies all the time, where the main character plans some elaborate surprise for the girl, or figures out a way to crash the big party or big wedding. In action films, it’s a little more technical. The character has to come up with a plan to save the girl, or take down the villain, or both. In The Matrix, Neo needs to save Morpheus. He tells Trinity the plan, they go outfit themselves with guns from the Matrix White-Verse, and they go in there to get Morpheus.

THE CLIMAX SCENE

This should be the most important scene in your entire script. It’s where the hero takes on the bad guy or tries to get the girl back. You should try and make this scene big and original. Give us a take on it that we’ve never seen in movies before. Will that be hard? Of course. But if you’re rehashing your CLIMAX SCENE of all scenes?? The biggest and most important scene in the entire screenplay? You might as well give up screenwriting right now. If there is any scene you need to challenge yourself on, that you need to ask, “Is this the best I can possibly do for this scene?” and honestly answer yes? This is that scene!

THE LOWER THAN LOWEST POINT

During the climax scene, there should be one last moment where it looks like your hero has failed, that the villain has defeated him (or the girl says no to him). Let’s be real. What you’re really doing here is you’re fucking with your audience. You’re making them go, “Nooooooo! But I thought they were going to get together!” This is a GOOD THING. You want to fuck with your audience in the final act. Make them think their hero has failed. I mean, Neo actually DIES in the final battle in The Matrix. He dies! So yeah, you can go really low with this “true lowest point.” If the final battle or confrontational or “get-the-girl” moment is too easy for our hero, we’ll be bored. We want to see him have to work for it. That’s what makes it so rewarding when he finally succeeds!

FLAWS

Remember that in addition to all this external stuff that’s going on in the third act (getting the girl, killing the bad guy, stopping the asteroid from hitting earth), your protagonist should be dealing with something on an internal level as well. A character battling their biggest flaw on the biggest stage is usually what pulls audiences and readers in on an emotional level, so it’s highly advisable that you do this. Of course, this means establishing the flaw all the way back in Act 1. If you’ve done that, then try to tie the big external goal into your character’s internal flaw. So Neo’s flaw is that he doesn’t believe in himself. The only way he’ll be able to defeat the villain, then, is to achieve this belief. Sandra Bullock’s flaw in Gravity is that she doesn’t have the true will to live ever since her daughter died. She must find that will in the Chinese shuttle module if she’s going to survive. If you do this really well, you can have your main character overcome his flaw, but fail at his objective, and still leave the audience happy (Rocky).

PAYOFFS

Remember that the third act should be Payoff Haven. You should set up a half a dozen things ahead of time that should all get some payin’ off here in the finale. The best payoffs are wrapped into that final climactic scene. I mean who doesn’t sh*t their pants when Warden Norton (Shawshank spoiler) takes down that poster from the wall in Andy Dufresne’s cell? But really, the entire third act should be about payoffs, since almost by definition, your first two acts are setups.

OBSTACLES AND CONFLICT

A mistake a lot of beginner writers make is they make the third act too easy for their heroes. The third act should be LOADED with obstacles and conflict, things getting in the way of your hero achieving his/her goal. Maybe they get caught (Raiders), maybe they die (The Matrix), maybe the shuttle module sinks when it finally gets back to earth and your heroine is in danger of drowning (Gravity). The closer you get to the climax, the thicker you should lay on the obstacles, and then when the climactic scene comes, make it REALLY REALLY hard on them. Make them have to earn it!

NON-TRADITIONAL THIRD ACTS (CHARACTER PIECES)

So what happens if you don’t have that clear goal for your third act? Chances are, you’re writing a character piece. While this could probably benefit from an entire article of its own, basically, character pieces still have goals that must be met, they’re just either unknown to the hero or relationship-related. Character pieces are first and foremost about characters overcoming their flaws. So if your hero is selfish, your final act should be built around a high-stakes scenario where that flaw will be challenged. Also, character piece third acts are about resolving relationship issues. If two characters have a complicated past stemming from some problem they both haven’t been able to get over, the final act should have them face this issue once and for all. Often times, these two areas will overlap. In other words, maybe the issue these two characters have always had is that he’s always put his own needs over the needs of the family. The final climactic scene then, has him deciding whether to go off to some huge opportunity or stay here and takes care of the family. The scenario then resolves the character flaw and the relationship problem in one fell swoop! (note: Preferably, you are doing this in goal-oriented movies as well)

While that’s certainly not everything, it’s most of what you need to know. But I admit, while all of this stuff is fun to talk about in a vacuum, it becomes a lot trickier when you’re trying to apply it to your own screenplay. That’s because, as I stated at the beginning, each script is unique. Indiana Jones is tied up for the big climax of Raiders. That’s such a weird third act choice. In Back To The Future, George McFly’s flaw is way more important than our hero, Marty McFly’s, flaw. When is the “lowest point before the third act” in Star Wars? Is it when they’re in the Trash Compactor about to be turned into Star Wars peanut butter? Or is at after they escape the Death Star? I think that’s debatable. John McClane never formulates a plan to take on Hanz in the climax. He just ends up there. The point is, when you get into your third act, you have to be flexible. Use the above as a guide, but don’t follow it exactly. A lot of times, what makes a third act memorable is its imperfections, because it’s its imperfections that make it unpredictable. If you have any third act tips of your own, please leave them in the comments section. Wouldn’t mind learning a few more things about this challenging act myself!