Search Results for: F word

Genre: Art-heist thriller/comedy

Premise: Art dealer Charles Mortdecai searches for a stolen painting rumored to contain a secret code that gains access to a Swiss bank account worth hundreds of millions of dollars.

About: Mortdecai will be directed by long time writer, sometimes director, David Koepp. This seems to be Koepp’s step into the directing big leagues, as he’ll be directing Gwyneth Paltrow, Ewan McGregor, Olivia Munn, and Johnny Depp. Mortdecai (based on a 4 book series and primed to be a franchise if it does well), was born out of the new partnership between Lionsgate and Oddlot. Oddlot is a financier/production company run by Gigi Pritzker. Pritzker is one of the richest families in the United States and owns the Hyatt Hotel chain. They’re also producing #1 Black List script, Draft Day. Lionsgate has recently evolved from a schlocky bad horror/sci-fi/supernatural mini-studio to a major player with its acquisition of Summit, which of course has one of the hottest franchises in town, The Hunger Games. Mortdecai is based on a book series by Kyril Bonfiglioli. This specific script is based on the fourth and final book in the series, which Bonfiglioli actually never finished, due to his death in 1985. It was completed by another author.

Writer: Eric Aronson (revisions by Peter Baynham and David Koepp – based on the books by Kyril Bonfigloli)

Details: 120 pages – June 20, 2013 draft

Mortdecai was adapted by a writer named Eric Aronson. Somehow, this very talented writer has only one produced credit, an abomination of cinema called “On the Line,” written in 2001, starring N*SYNC members Lance Bass and Joey Fatone. The sometimes semi-professional baseball player likes to take his breaks, waiting a full 12 years for his newest effort. Talk about patience.

To describe Aronson’s script is tough. It’s kind of like 1 part Sherlock Holmes, 2 parts Pink Panther, 3 parts Coen Brothers. The writing on display is very good, yet it isn’t afraid to moronify itself to Dumb & Dumber levels if necessary. For example, there are roughly 718,000 references to the main character’s mustache.

Basically our title character, Mortdecai, is an art thief. Or he used to be one. Or he still is one. It all depends on who you talk to. The former aristocrat with the most beautiful wife in the world isn’t doing so well these days, though. He owes Mother Britain 8 million dollars in back taxes, which means he’s only a few days away from losing his house, his car, and most likely that beautiful wife.

Lucky for Mortdecai, an opportunity arises. It seems that while being restored, a painting has been stolen. But not just any painting – “The Duchess of Wellington,” one of the most famous paintings in the world, due in part to the rumor that it may not even exist. The story goes, it was ordered destroyed by a king who didn’t like the painting, but was ripped off before the destruction could occur.

It went through many hands over the years and eventually ended up with the Nazis, and rumor has it that the Nazis coded a Swiss bank account number into the painting, which could be worth millions. The police tell Mortdecai that if he can find and bring back that painting, they’ll get rid of his tax problem.

Mortdecai accepts, employing his steady other half, bodyguard and womanizer, Jock. Along the way he finds out that others have caught wind of the painting’s re-emergence and want it as well. One of those people is nasty world criminal Emil Strago, who will presumably use the money from the painting’s secret code to support terrorism. The stakes have been raised.

Complicating his pursuit is his own wife, with whom Mortdecai is having problems. Not just because they’re broke and she doesn’t like his new mustache. But she doesn’t seem to respect him anymore. You get the sense that if he doesn’t pull this off, she’s probably going to leave him. And since she’s the biggest treasure of all, it’s very much in Mortdecai’s interest to find that damn painting before it’s too late!

I can’t stress enough how well Mortdecai is written. The kind of writing that I normally tell screenwriters to avoid turns into music when Aronson types, a possible result of his working with Joey Fatone and Lance Bass. The thing is, overly-descriptive writing tends to detract… UNLESS you’re great at it. And that seems to be the case with Aronson (and all the other writers involved). Here, for example, is an early description of Mortdecai’s mustache…

“A word about Mortdecai’s moustache — it’s a groomed affair and much care has gone into its cultivation, but there’s something a bit off about it. Simply put, everyone can agree he’d be much better off without it. Despite this, great admiration has been bestowed upon it by its owner.”

Could he have said simply, “Mortdecai’s moustache is a little off”? Of course. But there’s something about the extra attention to detail that gives us a better feel for the character. Here’s another description, this one about Mortdecai’s wife:

“The pricey authenticity of her blondeness is unimpeachable, and pleasant weather systems move in when she favors you with her wide and lovely smile.”

I mean, is that description totally necessary? No. But it’s so damn good and fun that I go with it.

In addition to the impressive description, this screenplay very wisely puts a new spin on the genre. In almost all of these art heist thrillers, there’s a painting in a museum or a rich person’s home that the main character must figure out how to steal from. Here, however, we (and the main character) don’t even know where the painting is. It’s already been stolen. In fact, we don’t even know WHAT the painting is. It isn’t revealed until later that it’s the famed “Duchess of Wellington.”

That’s another thing I liked about Mortdecai. It kept you guessing. And I believe these art thrillers are predicated on keeping you guessing. You must constantly surprise the audience. Remember, a thriller is supposed to do just that. THRILL. That doesn’t always mean thrill with a car chase or a shootout. It could mean using a reversal, a surprise, or a shocking reveal. When we find out, for example, that the painting was in Nazi hands and has a secret code embedded in it, we’re more than satisfied. This the kind of fun we came for.

Finally worth noting is that Mortdecai uses a time tested tool that rarely malfunctions. That is, of course, George Lucas’s favorite device, the MacGuffin! This is when you place one very important thing out there in your story THAT EVERYBODY WANTS. And then everybody goes after it. The reason the MacGuffin works so well is because it immediately makes every character ACTIVE. This means the script will always be packed with energy and purpose. Mortdecai’s after the painting. His wife is. Emil Strago is. The British police are after it. The Russians are after it. It’s kind of hard to fuck this up because no matter who you jump to, they’re always in an immediate active state. They’re always pursuing a goal. The MacGuffin isn’t for every story, but in the right story (Star Wars, Indiana Jones, Pirates of the Caribbean), it can turn your script into a beast.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[xx] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Seeing as the quadrology of books this script was based on was completed in the 70s and this weekend’s “Winter’s Tale” was based on a book published in the 80s, it doesn’t sound like a bad idea to scour Amazon and GoodReads for highly rated, long-since-forgotten books that don’t have options on them for potential adaptation material. Having an adapted screenplay carries with it a little more cache than an original script, since it’s already been proven in another medium. The problem is all the current stuff is snatched up. But tons of stuff in the 90s, 80s and 70s has been forgotten. Lots of opportunity there.

What I learned 2: The second of today’s “what I learned’s” has nothing to do with Mortdecai, actually, but a TV show!

So last night, Miss SS and I were watching The Bachelor and out of nowhere, a monster of a screenplay lesson popped up and helped Miss SS understand something she’d previously had a hard time grasping. I’ve been trying to tell her forever now how important it is to KNOW YOUR CHARACTERS before you write a script. Write down their bios, get into their past, know what’s led them to this point in their lives. She saw this approach as a creative handicap, though. She likes to discover her characters through dialogue, as they go through her story. Know too much, she said, and it stifles the creativity.

For those of you who don’t watch The Bachelor, it’s a reality show based on the very realistic notion of one man dating 25 women, eliminating them one at a time until there is one left. He then proposes to the final girl, only to break up with her a few months after the show has ended.

In this season, there’s this girl named Clare. Clare is 32, prickly, a little bitchy, jealous, passive-aggressively catty towards the other women, and always looks like she’s seconds away from having an emotional breakdown. Around this season’s bachelor, Juan-Pablo, she’s overly-flirty, eager-to-please, comes on too strong, and carries with her just a wisp of desperation. For all of these reasons, she’s not a household favorite.

Well tonight, Clare unloaded a bomb during one of her interviews. She is one of six sisters, and the only one who hasn’t yet married. “Ohhhh!,” Miss SS said. “No wonder she’s so desperate and catty. At 32 years old, the pressure to find a man must be intense.” That’s when the teachable moment occurred to me. “That,” I said, “is exactly the same thing you’re doing when you dig into your characters’ pasts before you write a script. If you know background stuff – like your unmarried character having 5 sisters, all of whom are married – you’ll be able to write that character way more specifically than had you known nothing.” Clare is the embodiment of a well-written character (despite the fact that she’s “real”). Every single aspect of her is informed by this delicate and pressure-filled reality of being “the last of the sisters.” That seemed to hit Miss SS. “Ooh,” she said. “You should put that on the blog.” And so I have!

Genre: Thriller/Horror

Premise: After suffering a devastating miscarriage, a young woman and her fiancé travel to Italy where she meets his family for the first time, but her grief turns to shock when the local doctor declares that she’s still pregnant.

About: This scored 10 votes on the latest Black List. Writer Christina Hodson still doesn’t have a produced credit, but the former development executive turned screenwriter is churning out lots of product in the hopes of getting there. She wrote previous Black List script, “Shut In” (a creepy script about a woman who must take care of her catatonic son), is adapting the thriller, “Unfogettable,” (about a man whose new wife is being harassed by his ex-wife) and also adapted the novel “Good People,” with James Franco starring (about a couple in debt due to expensive fertility treatments, who stumble across a solution when they find money in a deceased tenant’s apartment). Hodson making the Black List has been pointed out by some to be a rarity, after it was revealed that only 20% of the Black Lists selections are from female writers. While many declare this cause for alarm, when this very topic was brought up during Ladies Week on Scriptshadow, a commenter pointed out that if you go by the number of females who comment on Scriptshadow (few), any disparity in the male-female screenwriting community shouldn’t be surprising at all. If there aren’t that many female writers participating in the screenwriting community, why would it be surprising that they make up a small percentage of said community? This is a debate that will continue on until someone figures out the actual percentage of female writers pursuing screenwriting. Only then will we know if 20% on the Black List is a disproportionately low number.

Writer: Christina Hodson

Details: 96 pages

Winter’s Tale tagline: It’s 1846! No, it’s 2014! My horse can fly! Love is forever!

Winter’s Tale tagline: It’s 1846! No, it’s 2014! My horse can fly! Love is forever!

There is a new phenomenon sweeping the entertainment industry that’s making Gangnam Style look like Flappy Bird. It’s called Winter’s Tale! The runaway sweeping fairytale-slash-romance-slash-time-travel-slash-immortality flick from Akiva Goldsman killed it at the box office, finishing number 5 for the weekend. So many people have gone to see Winter’s Tale, they now have a name for those who have seen it five times or more (Winter’s Tailies). I’ve only seen the movie twice myself but I can confirm it’s every bit as heart-wrenching and mind-bending and utterly-baffling-that-someone-decided-to-make-it-ing, as has been rumored. The character-naming alone is downright historic. I mean, who hasn’t dreamed of naming their characters stuff like “Pearly Soames”? Or “Dingy Worthington”? Or “Cecil Mature”?

Oh! And guess who makes a cameo in the film! (Close your eyes if you’re going out to watch the movie this week and don’t want to know). None other than Jaden Smith’s dad! No word on who he plays, but estimates are on the flying unicorn that’s become so popular in the trailer. Whatever the case, you have to wonder what kind of dirt Akiva Goldsman had on Mr. Smith, Colin Farrell, and Russell Crowe to force them to be in this movie. Clearly something unsavory is going on here.

And if we’re being honest about unsavoriness, I have to admit I haven’t actually seen the film. Sadly, I am not three viewings away from being a Winter’s Tailie. So that was a lie. But a good lie. Because, I mean, come on. There’s no way this movie can be good. In fact, I’m convinced it was made by accident. Some editor in the Warner Brothers’ editing room has been randomly splicing together outtakes from the last 20 years’ worth of Warner Brother’s films and during the recent regime change, someone assumed that the finished product was a film they were releasing. That’s the only excuse for this film being released, right?

So how does all this factor into today’s script review? Well, Seed looks to be inspired by the classic Roman Polanski film, Rosemary’s Baby. Which was, of course, about a woman who has the devil growing inside of her. And since hell would freeze over before anyone were to go see Winter’s Tale, I figured they were a perfect fit to blog about.

Seed introduces us to a chick named Leila. Leila is 29, and one of those lucky gals who was able to snag a hot Italian guy. And she didn’t even have to use Tindr to do it. Tomaso, 33, is a hunk and a half, prime-rib Valentine’s Day meat, you might say, and head over heels in love with Leila. What he’s not in love with, though, is his past. Tomaso had such a bad experience back in his home-country, Italy, that he’s never gone back.

Unfortunately, Tomaso’s father is dying and the family thinks he should come say his goodbyes. Not only does Tomaso hate his dad, but he and Leila are having their own problems. He inadvertently impreg-sauced Leila, who’s since found out that the baby has died inside of her. Because surgery to remove the stillborn fetus is too expensive, all she can do is wait for it to pass through her body naturally.

The thing is, because the two have zilch in their bank account, they can’t even afford rent, so they figure they can kill 2 birds (and one father) with one stone, by going to Italy, saying goodbye, then mooching a room and meals for a couple of months while they look for some more permanent options.

When they get there, though, Leila is shocked to learn that Tomaso’s family is extremely rich. They live in a picturesque, sprawling vista at the top of a hill, and are quite famous in the area.

Tomaso’s father was a well-known “new-age” author in Italy, and preached about spirituality and one-ness and all that other new age gobbledy-gook that women love. But at his deathbed, we get a hint of why Tomaso hates his old man so much. With his last breath, the dad reaches up and rape-kisses Leila! It’s unsettling, and Leila is so not cool with it. Strangely enough though, a day later, the doctor says that that supposedly dead fetus in her isn’t dead at all. It’s growing! Yaaay!!! Or… not yay?

What happens next is pure Creepy Factor 9000, as Tomaso’s older sister Myrra starts teaching Leila the ways of her father, and Leila starts buying into it. She doesn’t think to question the people who live off the family’s land, who sleep in nearby housing, and who are starting to look an awful lot like a cult. Tomaso sees where this is going and does his best to convince Leila to leave with him. But Leila decides she’s staying, that she’s having her baby here. Regardless of what that baby is!

I really like Christina Hodson as a writer. I liked her script, Shut In. She knows how to come up with a concept and exploit it. That’s what screenwriting is all about. It’s finding a cool concept that people will want to pay to see. Then it’s figuring out all the scenes and characters and situations you can milk from that idea, so the audience (or reader) feels like they got their money’s worth.

The worst thing that can happen is when you promise an audience something, then give them something else (or barely give them anything at all). I recently re-watched the 1999 film The Haunting (with Catherine Zeta-Jones and Owen Wilson) wanting to see a film that really exploited the haunted house concept. Instead I got a bunch of over-the-top effects and a rambling storyline. When that happens, you feel gypped.

In this case, Hodson’s trying to write the next Rosemary’s Baby, and she just might have pulled it off. By taking the story out of the U.S. and into Italy, then involving a cult, you have enough external dressing to distract you from the fact that this is basically a remake. It’s a smart move. We’re all basically re-hashing plotlines from the movies we love. The problem is, if our creations are too similar to the movies they’re inspired by, they feel like inferior copies. So you have to change the key ingredients involved so they feel fresh.

Rosemary’s Baby happened in the most populated city in the world. So where does “Seed” take place? The countryside! It seems like a small change but because it changes every aspect of the visual surroundings, it’s actually quite dramatic.

If I have any issue with Seed is that it’s unapologetically formulaic. I mean, there are strong and unique choices made here, as I mentioned. But the way the story evolves and the way it sits squarely within its pigeon-holed genre, it feels a teensy bit generic. The thing that I’m realizing these days with the ever-evolving VOD market, is that these genre movies are being measured on whether they’re big enough to have a theatrical release or if they’re going straight to VOD. If they’re going to have a theatrical release, there needs to be something special in them (an amazing role for an actor, a unique twist that’s never been seen before, or a unique voice that an esteemed director is going to want to do something with).

I can honestly trace the moment studios got scared of giving films like this wide releases back to the film, The Rite. The movie simply didn’t have the muscle to be released on 3000 screens, and opened weakly as a result. Since then, something’s changed. Studios are more cautious when deciding which path to take these movies on.

Look at Robert Ben Garant and Thomas Lennon, two of the biggest comedy writers in the business. Well, their recent film, Hell Baby, went straight to VOD. Talk about a tough reality. However, then there’s The Conjuring, which probably went through this vetting process as well. In the end, The Conjuring was based on a real story, which makes the horror genre a lot easier sell to audiences. That was its X-factor.

Ironically, I believe Hodson’s other script, Shut In, does have this quality. It’s unique and different and I could see some weirdo hot-shot up-and-coming director wanting to do something fun with that.

None of this is a bad thing, of course. I still think this script rocks. But I’m learning that, with the market getting more and more competitive, particularly with horror films, you need to bring something big or different to the table to get that coveted theatrical release.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[xx] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Every writer needs an opposite-sex bullshit detector. If you’re a guy, give your script to a girl after you’re finished and have them “bullshit proof” all the female characters. Ditto if you’re a woman. Have a guy read your script with the focus on, “Would a guy ever act like this or do these things?” If you don’t, those characters are bound to come off a little false.

Get Your Script Reviewed On Scriptshadow!: To submit your script for an Amateur Review, send in a PDF of your script, along with the title, genre, logline, and finally, something interesting about yourself and/or your script that you’d like us to post along with the script if reviewed. Use my submission address please: Carsonreeves3@gmail.com. Remember that your script will be posted. If you’re nervous about the effects of a bad review, feel free to use an alias name and/or title. It’s a good idea to resubmit every couple of weeks so your submission stays near the top.

Genre: Dark Comedy

Premise (from writer): A colorful but washed-up bad boy recounts his epic rise and fall in Hollywood on an online video blog.

Why You Should Read (from writer): Imagine walking into Dylan’s Candy Bar in NYC and receiving a grab-bag of delicious wonderment– a daze of brilliantly colored candies in odd shapes, colors, and textures. In fact, when you first open the bag a pop of glitter explodes in your face. You suddenly get slapped on the back by Christopher Walken, then an adjacent clown blows a bull-horn in your left ear. You’re not quite sure what just happened, you don’t 100% understand… but you think you like it. That’s how reading this script feels.

Writer: Mayhem Jones

Details: 86 pages

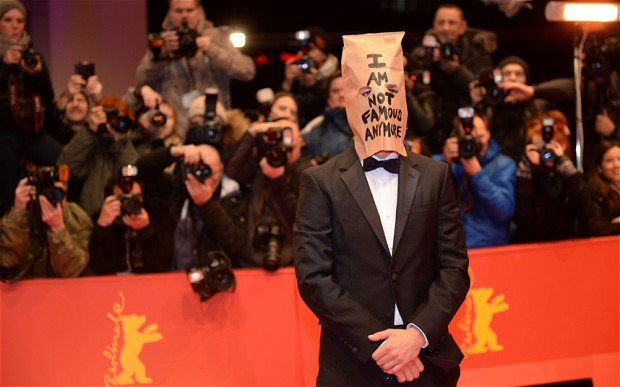

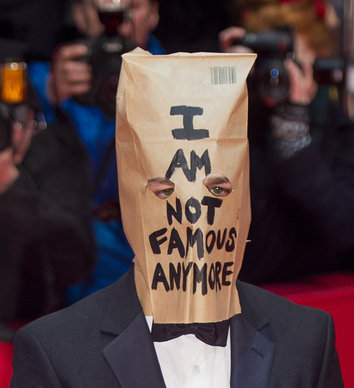

Today’s script seems apropos in the wake of Shia LaBeouf’s very public celebrity meltdown. He’s sorry. For what, he’s not saying. What’s eerie is that today’s protagonist, in a script written many months ago (I’m assuming), has a shockingly similar meltdown. Granted, there’s a little Charlie Sheen thrown in for good measure, but it’s weird. Then again, “Dexter Strange” is written with the kind of raw energy that one might assume could be birthed in a Red Bull infused 24 hour writing marathon. So maybe, just maybe, it was conceived in the wake of Shia’s “I Am Sorry” campaign. However, whereas Shia seems to speak by not speaking, Dexter Strange seems to speak by… speaking a lot. A really lot. There’s a lot a lot of speaking in this script. To give you a little preview, here’s a line from Dexter…

“If we work made-up jobs to earn made-up money, then the fact I’m an actor means my made-up job is a made-up job where I make-up being other made-up people in a made-up job I make-up to make made-up money.”

If you’re not prepared to read a lot of sentences like that, then Dexter Strange slash Shia LaBeouf slash Charlie Sheen probably isn’t for you. Was it for me? Let’s find out!

44 year old Dexter Strange is a former movie star. He’s still sexy. He’s still good-looking. But things aren’t going well for him lately. At the moment, he’s sitting in front of his computer, live video streaming his breakdown, which includes lots of drugs, lots of booze, and a couple of hookers shimmying about in the background.

The nice (or un-nice) thing about Dexter is he’s very forthcoming about his meltdown. Like he wants you to know all of it. He will talk and talk and talk and talk until there’s nothing left to say, then he’ll talk some more. Most of his talking has to do with his philosophies on life (there’s a lot of stuff like the “made-up jobs” observation above). Interspersed between these talkings, we get flashbacks of Dexter’s rise to fame.

If you can call it that. Dexter’s rise is surprisingly general. We only get these snippets of it here and there, like when he meets his agent, when he dumps his girlfriend, and when he fake-marries a trashy Lindsey Lohan clone. It’s what’s so strange about this script. For all the exceedingly specific dialogue and voice over, we’re not seeing nearly enough of Dexter’s life.

In the end (big spoiler alert), Dexter doesn’t make it. He kills himself. And I guess that means this lands somewhere between a cautionary tale, a tragedy, and a satire. Does it succeed at any of these? Honestly, I’m not sure. But what I am sure of is that it’s a hell of a ride while we’re trying to figure that out.

The first thing that comes to mind when you read “Dexter Strange” is not the story, or even the character. It’s the writing itself. It’s very fast, energetic, confident, delirious, crazed, as well as a number of other adjectives I can’t think of at the moment.

For the most part, I liked that. Because I’m used to reading a lot of boring writing when I pick up a script. Whether you like this story or not, the writing stays with you. And when the writing stays with the reader, that means the writer has a shot in this business. (#VOICEISIMPORTANT)

The problem with this type of writing, though, is that it’s very “look at me.” It’s more about the writing than the story, and while that works for awhile, it almost always becomes tiring. And in cases like this, where the writing is SO big and SO “in your face,” it can become irritating. I mean here’s one of Dexter’s many monologues, this one on page 13: “What is your thing? Ordaining pastors? Protected sex? Hey. Why don’t you blow my fuckin’ mind for once? You’re– we’re on Rumspriga now, OK! You can wander a little from the farm. Step astride the buggy. Halt churning that goddamn butter. Or do you miss–(flaps arms) BA-CAW! Runnin’ around with the chickens? BA-CAW! Marty. Remember Marty? No-name nothin’ feed corn farmer? Seriously. Inferior corn. Can’t even grow shit fit for human consumption– and he’d kill to be in your loafers right now. But who’s my best friend? Who drove me to Los Angeles, not even a blink, for an agent meeting? Do me a solid by doing me proud. Pretend Marty’s watching us right now– you’re on a screen! Hey, Marty! We’re on TV. Let’s do it. The rabbit hole beckons. Just a taste. A lick. A toe-dip. Here, a puff—“

It’s hard for a reader to take that kind of crazy for 90 minutes.

Assuming that works for the reader though, you’re still fighting an uphill battle with this structure. The script is essentially a ranting character intermixed with flashbacks of his rise to fame. There’s no real story here. We’re not pushing towards anything. We’re recalling everything. What I mean by that is, there’s nothing more to gain. There’s no goal. There’s nothing our character wants. Everything that’s relevant has already happened. And that means the story is only going backwards. A “backwards” story is hard to tell, because most audiences want to go forward. Ripley doesn’t recall the tough life that she had growing up. She goes to that planet to destroy the aliens. In “Dexter Strange,” we’re just remembering a very sad man’s life where very sad things happened.

Now if you want to play this as a tragedy, that’s a different deal. But the thing with tragedies is we still need that building-up period. We need the happy stuff. The good times. A world that our character can fall from grace from. In Goodfellas, Henry Hill achieves a hell of a lot and lives a wonderful life before he starts to fall. As does our friend Tony Montana in Scarface. In “Dexter Srange,” there’s never really any good times. Dexter is screwed pretty much from the beginning (he’s forced to give a producer a hand job on his very first meeting for a role).

When you throw in a main character who’s hard to like (this guy’s an asshole to pretty much everyone), well, you’ve made things really hard for yourself.

You guys know me by now. I don’t respond to stuff that’s all negative, all sad. And to drive that point home, I stopped reading this a couple of times to go read THIS post. That tells you how much this was getting me down.

But I don’t think Mayhem should be discouraged here. She’s created a character that an actor would love to play. And she clearly has a ton of talent. I often gauge a writer’s ability with the question, “Could the average writer do this?” There is nobody else in the world who could’ve written this script but this writer. So that’s saying something. Now if she could just harness her powers and bring that talent to something a little more accessible, I’d be in.

Script Link: The Tragic Life Of Dexter Strange

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Style over substance only works for about 15-20 pages before the reader starts to check out. Doesn’t matter how good of a wordsmith you are, how good you are with prose. 15 pages with all glitz and no story? Readers start skimming.

A friend of mine gave me a script last week with that desperate look in his eyes. You know the look I’m talking about. That tired bloodshot I’ve-been-crying-for-seven-days Shia LaBeouf “I Am Not Famous Anymore” eyes-behind-the-paper-bag look? I looked at my friend and said, “Are you okay?” All he responded with was: “Second act… (then he shook his head) second act.” That was it.

For centuries, screenwriters have stood on the precipice of that second act, looked out at its grand canyon of unknowns, and given up right then and there. I honestly believe that the second act is what sends 80% of the writers who come to Hollywood, looking to break in, back to where they came from. Because when you think about it, the first act is easy. You’re just setting up your concept and your protagonist, something you probably already knew just by coming up with the logline.

But the second act is different. That’s because the second act is where you actually have to BE A WRITER. You have to know how to, you know, craft a story n’ stuff. That takes two things. Practice and Know-how. I can’t do the practice for you. But I can give you the know-how. Now what I’m about to tell you is assuming you already know the basics of structure (and if you don’t, you should buy my book, dammit. It’s only $4.99 right now!). First act is 25% of your screenplay, second act is 50%, third act is 25% (roughly). You should know how to give your protagonist a goal (find the Ark, defeat the terrorists, get your life back on track, a la Blue Jasmine) that is driving him through the story, as well as understand how to apply stakes and urgency to that pursuit. Assuming you’re on top of that, here’s the rest of what you need to know.

Character Development

One of the reasons the first act tends to be easy is because it’s clear what you have to set up. If your movie is about finding the Ark, then you set up who your main character is, what the Ark is, and why he wants to get it. The second act isn’t as clear. I mean sure, you know your hero has to go off in pursuit of his goal, but that can get boring if that’s the ONLY thing he’s doing. Enter character development, which really boils down to one thing: your hero having a flaw and having that flaw get in the way of him achieving his goal. This is actually one of the more fun aspects of writing. Because whatever specific goal you’ve given your protag, you simply give them a flaw that makes achieving that goal really hard. In The Matrix, Neo’s goal is to find out if he’s “The One.” The problem is, he doesn’t believe in himself (his flaw). So there are numerous times throughout the script where that doubt is tested (jumping between buildings, fighting Morpheus, fighting Agent Smith in the subway). Sometimes your character will be victorious against their flaw, more often they’ll fail, but the choices they make and their actions in relation to this flaw are what begin to shape (or “develop”) that character in the reader’s eyes. You can develop your character in other ways (via backstory or everyday choices and actions), but developing them in relation to their flaw is usually the most compelling part for a reader to read.

Relationship Development

This one doesn’t get talked about as much but it’s just as important as character development. In fact, the two often go hand in hand. But it needs its own section because, really, when you get into the second act, it’s about your characters interacting with one another. You can cram all the plot you want into your second act and it won’t work unless we’re invested in your characters, and typically the only way we’re going to be invested in your characters is if there’s something unresolved between them that we want resolved. Take last year’s highest grossing film, The Hunger Games. Katniss has unresolved relationships with both Peeta (are they friends? Are they more?) and Gale (her guy back home – will she ever be able to be with him?). We keep reading/watching through that second act because we want to know what’s going to happen in those relationships. If, by contrast, a relationship has no unknowns, nothing to resolve, why would we care about it? This is why relationship development is so important. Each relationship is like an unresolved mini-story that we want to get to the end of.

Secondary Character Exploration

With your second act being so big, it allows you to spend a little extra time on characters besides your hero. Oftentimes, this is by necessity. A certain character may not even be introduced until the second act, so you have no choice but to explore them there. Take the current film that’s storming the box office right now, Frozen. In it, the love interest, Kristoff, isn’t introduced until Anna has gone off on her journey. Therefore, we need to spend some time getting to know the guy, which includes getting to know what his job is, along with who his friends and family are (the trolls). Much like you’ll explore your primary character’s flaw, you can explore your secondary characters’ flaws as well, just not as extensively, since you don’t want them to overshadow your main character.

Conflict

The second act is nicknamed the “Conflict Act” so this one’s especially important. Essentially, you’re looking to create conflict in as many scenarios as possible. If you’re writing a haunted house script and a character walks into a room, is there a strange noise coming from somewhere in that room that our character must look into? That’s conflict. If you’re writing a war film and your hero wants to go on a mission to save his buddy, but the general tells him he can’t spare any men and won’t help him, that’s conflict. If your hero is trying to win the Hunger Games, are there two-dozen people trying to stop her? That’s conflict. If your hero is trying to get her life back together (Blue Jasmine) does she have to shack up with a sister who she screwed over earlier in life? That’s conflict. Here’s the thing, one of the most boring types of scripts to read are those where everything is REALLY EASY for the protagonist. They just waltz through the second act barely encountering conflict. The second act should be the opposite of that. You should be packing in conflict every chance you get.

Can someone PLEASE write a buddy-cop movie about Shia’s bag and Pharrell’s hat?

Can someone PLEASE write a buddy-cop movie about Shia’s bag and Pharrell’s hat?

Obstacles

Obstacles are a specific form of conflict and one of your best friends in the second act because they’re an easy way to both infuse conflict, as well as change up the story a little. The thing with the second act is that you never want your reader/audience getting too comfortable. If we go along for too long and nothing unexpected happens, we get bored. So you use obstacles to throw off your characters AND your audience. It should also be noted that you can’t create obstacles if your protagonist ISN’T PURSUING A GOAL. How do you place something in the way of your protagonist if they’re not trying to achieve something? You should mix up obstacles. Some should be big, some should be small. The best obstacles throw your protagonists’ plans into disarray and have the audience going, “Oh shit! What are they going to do now???” Star Wars is famous for one of these obstacles. Our heroes’ goal is to get the Death Star plans to Alderaan. But when they get to the planet, it’s been blown up by the Death Star! Talk about an obstacle. NOW WHAT DO THEY DO??

Push-Pull

There should always be some push-pull in your second act. What I mean by that is your characters should be both MAKING THINGS HAPPEN (push) and HAVING THINGS HAPPEN TO THEM (pull). If you only go one way or the other, your story starts to feel predictable. Which is a recipe for boredom. Readers love it when they’re unsure about what’s going to happen, so you use push-pull to keep them off-balance. Take the example I just used above. Han, Luke and Obi-Wan have gotten to Alderaan only to find that the planet’s been blown up. Now at this point in the movie, there’s been a lot of push. Our characters have been actively trying to get these Death Star plans to Alderaan. To have yet another “push” (“Hey, let’s go to this nearby moon I know of and regroup”) would continue the “push” and feel monotnous. So instead, the screenplay pulls, in this case LITERALLY, as the Death Star pulls them in. Now, instead of making their own way (“pushing”), something is happening TO them (“pull”). Another way to look at it is, sometimes your characters should be acting on the story, and sometimes your story should be acting on the characters. Use the push-pull method to keep the reader off-balance.

Escalation Nation

The second act is where you escalate the story. This should be simple if you follow the Scriptshadow method of writing (GSU). Escalation simply means “upping the stakes.” And you should be doing that every 15 pages or so. We should be getting the feeling that your main character is getting into this situation SO DEEP that it’s becoming harder and harder to get out, and that more and more is on the line if he doesn’t figure things out. If you don’t escalate, your entire second act will feel flat. Let me give you an example. In Back to the Future, Marty gets stuck in the past. That’s a good place to put a character. We’re wondering how the hell he’s going to get out of this predicament and back to the present. But if that’s ALL he needs to do for 60 pages, we’re going to get bored. The escalation comes when he finds out that he’s accidentally made his mom fall in love with him instead of his dad. Therefore, it’s not only about getting back to the present, it’s about getting his parents to fall in love again so he’ll exist! That’s escalation. Preferably, you’ll escalate the plot throughout the 2nd act, anywhere from 2-4 times.

Twist n’ Surprise

Finally, you have to use your second act to surprise your reader. 60 pages is a long time for a reader not to be shocked, caught off guard, or surprised. I personally love an unexpected plot point or character reveal. To use Frozen, again, as an example, (spoiler) we find out around the midpoint that Hans (the prince that Anna falls in love with initially) is actually a bad guy. What you must always remember is that screenwriting is a dance of expectation. The reader is constantly believing the script is going to go this way (typically the way all the scripts he reads go). Your job is to keep a barometer on that and take the script another way. Twists and surprises are your primary weapons against expectation, so you’ll definitely want to use them in your second act.

In summary, the second act is hard. But if you have a structural road-map for your story (you know where your characters are going and what they’re going after), then these tools should fill in the rest. Hope they were helpful and good luck implementing them in your latest script. May you be the next giant Hollywood spec sale! :)

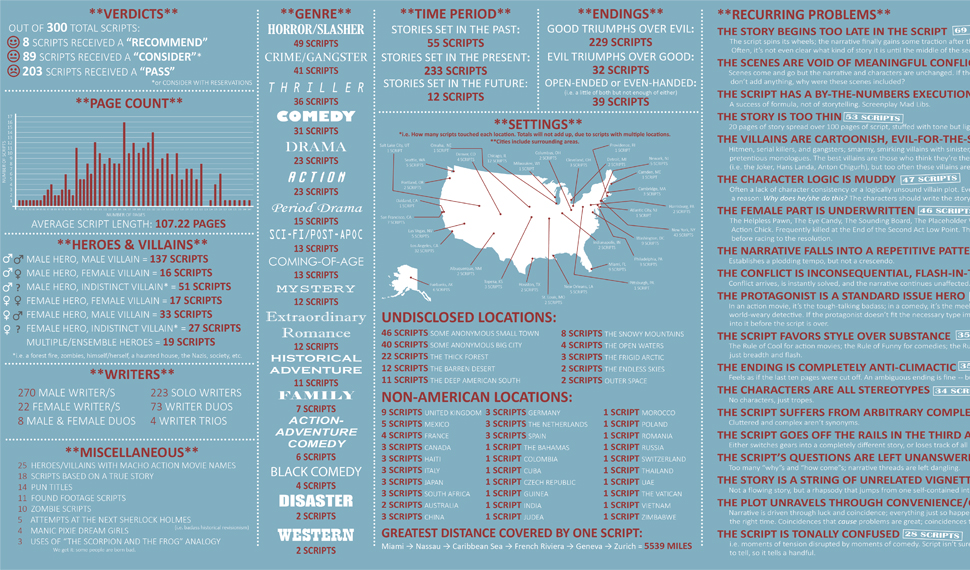

One of the best things to happen to the screenwriting community was this info-graphic. An industry reader read 300 scripts and tracked very specific data on all of them, which allowed him to create a breakdown of all the faults he found. Yeah yeah, that’s kind of depressing. But it’s also helpful! Because guess what? I see these exact same things all the time too and I just say, “Ahhhhhh! Why can’t writers NOT DO these things??” If they understood these pitfalls, screenplays across the world would be so much better. Of course, everybody’s in a different place and we’re all learning at different rates, so yeah, I guess you have to take that into account. But not after today fellas and gals. After today, you are NOT going to be making these mistakes ANY MORE. So, here’s our mystery infographic maker’s TOP 5 mistakes he encountered while reading 300 screenplays, along with my own precious surefire ways to avoid making those mistakes yourselves.

BIGGEST PROBLEM – “The story begins too late in the script.”

(69 scripts out of 300)

Oh my gosh golly loggins, yes, yes AND YES AGAIN. This is SUCH a huge problem in amateur scripts. It’s the radiation poisoning of script killers. What I mean by that is it’s a slow painful way to kill off a script, as the story keeps going, and going, and going, and nothing resembling a story is emerging. This usually happens for a couple of reasons. First, writers can get lost in setting up their characters and world. Sure, setting that stuff up is important, but if you’re not careful, 30 pages have gone by and all you’ve done is set everything up! You haven’t actually introduced a plot. Also, new writers, in particular, use three or four scenes to make a point, whereas pros know to make the point in one. Readers don’t need to be repeatedly told things to get them. Yes, Mr and Mrs. Johnson are having marital problems. But showing four separate fight scenes to get that point across is kinda overkill, don’t ya think?

THE FIX

The first act is the easiest act to structure and, therefore, one you should structure. Somewhere between pages 1 and 15, give us an inciting incident. That means throw something at your main character that shakes his life up and forces him to act. I was just watching the most indie of indie films, “Robot and Frank,” about an old man losing his senses, and his son gets him a robot to take care of him. Guess when the robot shows up? Within the first 12 minutes! So even in an indie movie about old people, the story is STARTING RIGHT AWAY. If they’re doing it, so should you!

SECOND BIGGEST PROBLEM – “The scenes are void of meaningful conflict.”

57 out of 300 scripts

It personally took me a long time to figure this out. “Oh wait,” I realized when I used to spend 72 hour shifts plastered on my laptop screen, “you mean two characters sitting around and talking about life isn’t interesting??” Or a series of scenes with my main character enjoying life could become boring to someone?? It wasn’t until I realized that every single scene needed to have conflict on SOME LEVEL that I truly understood what “drama” meant. Every single scene needs drama, and you can’t have drama without conflict.

THE FIX

Whenever you write a scene, you need to ask yourself, “Where’s the conflict here?” If there isn’t any, add some. I’m going to help you out. Two of the most powerful forms of conflict you can draw on are over-the-table and under-the-table. Over the table is more obvious. Think of two characters confronting each other, a girlfriend who’s just found out her boyfriend has cheated on her. She storms into his apartment and starts yelling at him. They fight it out. Assuming we’re interested in the characters and you’ve set this moment up, it should be a good scene. The far more interesting conflict to use, however, is under-the-table. This is when characters are pushing and pulling at each other, but underneath the surface. For example, let’s say this same girl comes home, but instead of telling her boyfriend what she knows, she acts like everything’s fine. They have dinner, and she slowly starts asking questions. They seem innocent (“What did you do yesterday? Can I use your phone to call a friend?”) when, in actuality, she’s trying to get her boyfriend to admit his guilt, or catch him in his lies. Of the two options, under-the-table conflict is always more fun, but as long as there’s SOME conflict in the scene, you’re good (note, there are other forms of conflict you can use. These are just two options!).

THIRD BIGGEST PROBLEM – “The script has a by-the-numbers execution.”

53 out of 300 scripts

Has someone been spending too much time trying to fit their story into Blake Snyder’s beat sheet? Have you become so obsessed with The Hero’s Journey that you’re starting to pattern your breakfast after it? We were just talking about this yesterday with The Lego Movie script. If you follow formula too closely, it becomes extremely hard for your script to stand out. When I see this, it’s almost always coupled with a boring writing style. The combination leaves the script with no unique identifying value. It is the “anti-voice” script, the equivalent of one of those knock-off Katy Perry songs. The writers most susceptible to this actually are NOT new writers, but writers on their 4th or 5th script. That’s because new writers don’t know about rules yet. It’s the writers who are starting to put in the work and learn how to tell a good story, who then follow the advice a little too literally.

THE FIX

You have to break a few rules. Your script will never stick out unless you take some chances. And actually, the rules you break define your script. For example, using an unlikable protagonist. It goes against conventional wisdom, but if you have a good reason for it and it works for the story, then take the chance. The most susceptible writers to this kind of mistake are SCARED writers. Writers who fear taking chances. They want to play with their story in their safe little bubble. I say surprise yourself every once in awhile. Try something with a plot point you never would’ve normally done. See where it takes you. If you’re surprised, there’s a good chance the audience will be too. And if this is a serial problem for you (everyone’s always telling you your scripts is very “by-the-numbers”), I suggest writing an entire script that’s completely weird and totally different from anything you’ve done before. Tell a story like 500 Days of Summer, where you’re jumping around in time, or Drive, where you’re crafting the story with actions as opposed to dialogue. You’re not going to grow unless you take chances.

FOURTH BIGGEST PROBLEM (tie) – “The story is too thin.”

53 out of 300 scripts

This is usually a problem that begins at the concept stage. Someone picks an idea that doesn’t have enough meat in it. Sofia Coppola’s “Somewhere” is a good example of this. “A guy spends time with his daughter.” When there’s not enough meat, there isn’t enough for your characters to do, and so long stretches of the script go by where nothing happens. Since you’re not a writer-director like Sofia and therefore don’t have funding to make these movies, your scripts can’t afford this pitfall. What it really comes down to is an absence of plot points, the major pillars in your scripts that slightly change the story or the circumstances surrounding your characters, sending it in a different direction.

THE FIX

First, make sure your concept packs a lot of story opportunities. A script like Inception – where teams of people are travelling inside minds – there’s ample opportunity to cram a ton of story into those 120 pages. Also, keep your plot points close together. Something that changes the story slightly or keeps it charging forward should be happening every 10 to 15 pages. So let’s say you’re writing a script about a guy who wins the lottery. On page 20, his ex-girlfriend who dumped him may show up at his door. On page 32, he finds out he’s being sued by someone who says he stole the lottery ticket from him. On page 46, he gets robbed coming out of the bar. Make sure things keep happening consistently during the script to avoid the “thin” tag.

FIFTH BIGGEST PROBLEM – “The villains are cartoonish, evil for-the-sake-of-evil.”

51 out of 300 scripts

This is almost exclusively a beginner mistake. Beginners remember their favorite villains as being over-the-top and quirky in one particular area (an accent, an eye-patch) and think, “Perfect! That’s all I need to do for my villains too!” So they only focus on how the villain acts on the OUTSIDE as opposed to what’s going on on the inside.

THE FIX

With villains, you have to start on the inside. I KNOW people hate doing all this work, but I’d strongly suggest busting out a new Word Doc and writing down as much as possible about your villain. Find out where he grew up, what his childhood was like (was he bullied? Abused? Ignored? Alone? A victim of affluenza?) Any of these could explain why he became the way he did. The more you know about your villain, the less cliché he’s going to be. And remember, the villain always believes he’s the hero. He truly believes in his cause. One of the easiest ways to lead your villain to the cliché troth is to assume he knows he’s bad and loves it. Villains are much more horrifying when, like Hitler, they actually believe what they’re doing is right.