Search Results for: F word

Get your script reviewed!: To submit your script for an Amateur Review, send in a PDF of your script, along with the title, genre, logline, and finally, something interesting about yourself and/or your script that you’d like us to post along with the script if it gets reviewed. Use my submission address please: Carsonreeves3@gmail.com. Remember that your script will be posted. If you’re nervous about the effects of a bad review, feel free to use an alias name and/or title. It’s a good idea to resubmit every couple of weeks so your submission stays near the top.

Genre: Drama/Action/Period/Western

Premise: (from writer) When a woman is kidnapped in Texas during the Dust Bowl, her husband embarks on a harrowing odyssey where he’s forced to confront danger in the forms of Mother Nature and man and also the mysterious past he buried years ago.

Why you should read: (from writer) Who am I? I’m 28 years old, live in Boston and have a day job in PR. For the last several years I’ve been moonlighting , weekending and every-free-fucking-second-I-have-ing as a writer. I’m hell bent on breaking in, by any means necessary. Anyway, back to the script. Sunny Side of Hell is set during a time where most us who frequent SS wouldn’t have lasted a week — the Dust Bowl. My grandparents actually lived through it and their stories set the backdrop for SHOH. The script, although a first draft, has a page-turning plot, interesting characters, compelling themes and a couple twists and turns to keep everyone locked in.

Writer: John Eidson

Details: 118 pages

Scriptshadow pick for Sam: SCOTT EASTWOOD!

Scriptshadow pick for Sam: SCOTT EASTWOOD!

Oh boy. Not a period piece. When I see 1 am and “period piece” on the same computer screen, a part of my script-reading mojo dies. It’s not that I don’t like period pieces. Two of my top 5 favorite unproduced scripts are period pieces. It’s just that when you’re stuck reading a bad period piece, it’s a lot worse than being stuck reading a bad present piece. They’re slower. They’re over-described. They’re mired in that drab “history lesson” snore-y fashion.

BUT! But when they’re good, they’re good. And you know what I’ve found? I’ve found that the writers of period pieces, on average, are usually better writers than their contemporary cohorts. I know that sort of contradicts what I just said, but hear me out. When someone wants to write a period piece, they’re usually a pretty smart guy. Most history buffs are knowledgeable folks. So there tends to be more depth to their work than the average script. Whereas a lot of contemporary writers who have more marketable concepts tend to write more from a “I like movies, so I can do it too” perspective. They don’t have that same appreciation for how difficult it is to create an imaginary world. So there isn’t as much attention paid to depth and detail.

So if we could somehow MARRY these two types of writers into a high concept detail-specific super cyborg writer… why, we could print money. Hmm, a cyborg writer. Now that’s an idea. I’m gonna look into that. But in the meantime, let’s take a look at John Eidson’s script. We’ll see if he’s one of those rare writers that can make a period piece fly.

Everything’s bigger in Texas. Like dust storms in the 1930s. Yup, try to plant an orange tree back then and it’ll be more like Tropican’ta than Tropicana, if you know what I mean. You see, before there were sharknados? There were dustnados. And maybe they didn’t have Great Whites doing 360s inches from your face, but if you ever got some dust in your eye? Well, shoot. You weren’t going to be opening that eye until AT LEAST tomorrow morning.

35 year-old husband Sam is trying to make the best of a situation that’s looking increasingly dire. You can’t grow crops in dust. So he and his wife Hannah are looking at all options in the survival game. One of those options is to take a big hunk of money from the town judge, Reginal Barron (who also happens to be Hannah’s father), and move west, where they haven’t figured out how to screw up crop fields yet.

Sam would rather starve than take handouts from Asshole Von Barron, whom he figures is enacting some scheme to separate him from his wife. So he tells him to dust off. That whole skirmish becomes secondary, however, when a day later Hannah is kidnapped! Turns out someone wants their brother out of jail, and they figure they’ll use the judge’s daughter for a trade.

Sam works with Barron to do the trade, but when he gets to the drop-point, the only wife waiting for him is a couple of smith and wessons! This is the kind of three-way I don’t want any part in! Bang bang. Bang some more, and somehow everybody’s dead except for Sam. So Sam keeps following Hannah’s trail, willing to go through hell or swirling dust to make sure the “death til you part” part of his vows doesn’t happen yet.

Along the way, Sam runs into a stampede of jackrabbits (not kidding), a sickly leatherface like family (sorta kidding), and some lesbian cannibals (definitely not kidding). In the end, he’ll learn the truth about his wife, and (spoiler) have to team up with his mortal enemy to take down the big bad shocking puppeteer of this farce of a kidnapping.

Okay, I’ve watched Miley Cyrus’s “We Can’t Stop” video, so I can safely say that I’ve seen everything. But Sunny Side of Hell is like Miley Cyrus’s long lost screenplay cousin. I mean, this is one weird little script. Case in point. I’ve never seen a jack-rabbit stampede crashing a 1930s motorcycle and turning our protagonist into road goo before. So Eidson gets a point for that.

But man, I mean, as for the rest, I don’t know where to stop. Because I can’t stop. And we won’t stop. I mean, know where to start. START. No, I’m not twerking right now.

So here’s the thing with this script. It’s very well-written. When you’re writing a period piece, you have to establish mood. And you do that by crafting words in a pleasingly descriptive way. A.K.A. Unlike that sentence I just wrote. Eidson is really good with description. There are a lot of paragraphs like these: “Golden stalks of wheat swaying gently from side to side, set against a great pale blue sky. The scorching sun roasts the fragile stalks.” – It’s really the perfect balance. It’s not over-described. It’s accurately described, and doesn’t give us any extra words or sentences we don’t need. That’s what I like. I don’t want the writing to be too flashy. I like it to be invisible, with just enough depth and imagery to place me in the world.

Ditto with the dialogue, which was consistently authentic. I mean, I could pick a hundred lines out of this script that sounded just like this one: “Lots a that goin’ on these days. Dust storms scaring folks outa’ here faster than a bee-stung stallion. Good for you fellers though I suppose?” That sounds to me like a real Texan from 1930s middle-of-nowhere, right?

But just like everything in this script, where there was a positive, it was coupled with a negative. There were sooooo many errors in here, and that’s WITH the “newer version” Eidon sent me. I’m not sure there’s a single correct usage of “your” in here. “Sees” is written as “see’s” for some reason. And there were just a lot of mistakes like that. So this beautiful writing was constantly being pulled down by silly mistakes.

As for the story, I have to admit I wasn’t sure what Eidon was doing for awhile. We start off with a clear goal – Sam’s wife’s been kidnapped. He must go after her. However, it’s as if the immediacy and importance of that goal are constantly thrown out the window in favor of these strange stops along the way. I have no idea why a 15 page chunk was dedicated to this strange sickly band of folks holed up in their mansion. It just felt like a completely random diversion. Ditto the lesbian cannibals.

After awhile, I began to wonder if what Eidon was trying to do was use this forum as a sort of cinematic postcard for the Dust Bowl. Because showing the scorched fields and the sickly families, at a certain point, became more important than our main character’s pursuit of his kidnapped wife. And while I sometimes found these people interesting, in the back of my head I’m going, “Why the hell is he hanging out with these people when his wife is in danger of being murdered at any minute?”

In addition to that, Eidon telegraphed his twist way too clearly. Going to be some southern spoilers here. By having the rift between Sam and Barron so out in the open and obvious, in combination with Sam showing up at the drop point only to find out it was a set-up, I mean it was pretty obvious to me at that point that Barron was the one setting him up. Yet another 60 pages go by until we’re told this. In the next draft, I’d advise Eidon to make Barron much more subtle, or maybe make him the opposite of how he is now – overly nice, so we don’t suspect him. Because that twist is supposed to be a big moment, and we were way ahead of it.

Despite all that, there’s definitely something here, if not with this particular script, then with the writer. There are two questions I ask myself after I finish a script in order to determine how I REALLY feel about the screenplay 1) Do I want to push this up the ladder (pass it on to people)? And if not, then 2) Do I want to read what this writer writes next? In this case, I definitely want to read what Eidson writes next. But right now, he’s not there yet. He needs to work on focusing his narrative and not losing sight of the plot. This drifted too far off the main road too many times, and in the process, got stuck in the dust. But the great thing about writing is you learn something with every script you write. Hopefully this only makes Eidson stronger.

Script link: Sunny Side of Hell

SCRIPT

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

WRITER

[ ] still figuring out basic English

[ ] needs to write a lot more scripts

[x] someone to keep an eye on

[ ] this guy should already be a pro

[ ] the next coming of Aaron Sorkin

What I learned: Guys guys guys. I can’t stress this enough. Please send your best stuff the first time out. When you e-mail a day later and say, “Here’s the new one. Don’t use the last one,” I die a little inside. Because I don’t understand why you didn’t make it perfect the first time. You’re basically admitting that you didn’t meticulously make sure everything was perfect the first time out, which is what you need to do! If you’ve done a major rewrite, that’s different. But whenever you’re submitting a draft of a script, make sure it’s “the one.” And remember that I’m SUPER LENIANT about this compared to the rest of the industry, who probably will delete you forever if you try and pull that stunt.

What I learned 2: There’s this new thing being done in scripts that I don’t know if I’m on board with. When a line or two of description interrupts a person speaking, and that same person speaks again, the writer doesn’t include the name above that second chunk of dialogue. So it’ll look like this (my apologies for not being able to format it correctly).

JOE

I was racing for years, Mac. YEARS I say. But it wasn’t until I got the cancer that I realized how much I loved cycling. It’s funny how that is, right? How you don’t know what you got until it’s gone? But that’s when they hit me with the whopper. It was ass cancer. Ass cancer. I would never be able to sit on a motorcycle again.

Mac looks at Joe before finally reaching over and giving him a hug. It’s emotional for both of them.

Maybe if I had got more of these from Mom, I never would’ve got the ass cancer. Never would’ve got it…

So the name “JOE” should be above the line that starts with “Maybe…” but in this new format people are using, they don’t do it. Does this make it easier to read? That’s debatable. One less name to ingest means possibly. The thing is, whenever I see that, I THINK about it. And that’s the problem. I mentally stop for a second and THINK about how the writer’s using this unorthodox device, which takes me out of the story for a second. And as a writer, your job is to NEVER let your reader out of your spell.

Last week we discussed box office surprises and how those movies’ screenplays factored into their success. The idea is that when something unexpected happens in this industry, we, as writers, should know why it happened, so we can then use that knowledge in our own writing. Well today, we’re going to do the opposite. We’re going to look at some box office duds and see if we can’t figure out why they dudded. Again, the more knowledge we have, the better equipped we are to find success.

As I noted last week, directing, marketing and star power are all going to play a big role in a movie’s success. But everything stems from the screenplay. When you’re talking about the reasons for a box office failure (from a screenwriting perspective), you’re talking about two things. You’re talking about the concept, that 3-5 second pitch you can convey on a poster or billboard, and you’re talking about the story, since most trailers are going to convey the gist of your story within their two-minute running time. All else being equal, if nobody shows up to your movie, you can probably blame one of those two things.

The Lone Ranger

Projected Box Office: 250-300 million

Actual Box Office: 90 million

There are tons of theories on why this movie bombed. Even Johnny Depp has one (the American press conspired to destroy it). Many of these theories are probably right, but I’ll tell you something I noticed that not a lot of people talked about. When you watched The Lone Ranger trailer, you saw absolutely nothing new. Train chases, seen’em. Cowboys, seen’em. Indians, seen’em. Shootouts, seen’em. There wasn’t a single thing in that trailer that I hadn’t seen before. And if you’re writing a summer blockbuster script, and you aren’t giving us something we haven’t seen before, you may as well throw in the white flag, because audiences aren’t going to show up. The summer season is the “Thrill Season” for the movie business, and you gotta knock us out if you expect to compete. I mean look at the movie that came out last weekend, Gravity. That’s the perfect example of something new and different and fresh we HAVEN’T seen before, which is why so many people showed up for it.

R.I.P.D.

Projected Box Office: 130-150 million

Actual Box Office: 33 million

I actually thought this script was pretty good. Not great. But fun. However, the exact issue I spotted during that first read was exactly what doomed it. R.I.P.D. felt too similar to another film franchise – Men In Black. This is one of the trickiest games you play as a writer because you’re told to write something similar enough to other films that studios can envision it, but fresh enough that audiences won’t see it as old hat. R.I.P.D., in its trailer, felt too similar to a huge franchise and the reason that’s a killer is because even if you do a really good job of copying that franchise (or film), you’ll still be seen as the “lower quality” version of it. Now you can sometimes circumvent this issue if there’s been enough time between the film you’re copying and the one you’re releasing, but Men In Black 3 had just come out a year earlier, so people were bound to see this as Copycat Nation. Always have something different about your screenplay. If it’s too similar to something else we’ve seen, we’re on to the next script.

After Earth

Projected Box Office: 140-160 million

Actual Box Office: 60 million

I think the main reason this movie didn’t do well was the casting. There’s something about Will Smith doing a movie with his teenage son that gets people riled up. A father who can hand you the starring role in a giant effects-driven action movie reeks of the worst form of entitlement, right? In this country, we like to see people earn it. And while I know Jayden Smith did well with Karate Kid, I think America’s still waiting for him to prove himself before he’s ready for major action parts. With that said, this script didn’t open THAT terribly. It made 27 million dollars on its opening weekend. So if it really impressed its audiences, it could’ve made 75, maybe even 90 million dollars from word-of-mouth. So why didn’t it? Well, I noticed something about this film in retrospect that I now believe is killing all of M. Night’s films. They’re all so MONOTONE. Every character is one-note. They’re either sad, angry, or a combination of the two. The obsession with this downbeat tone results in audiences leaving the theater… down. And if moviegoers are leaving a movie down, do you think they’re running off to their friends to tell them to see the movie? Of course not. This when you had two of the more charismatic actors in the world!

Man On A Ledge

Projected Box Office: 65-75 million

Actual Box Office: 18.6 million

It’s too bad this movie bombed because I heard the original writer is a really nice guy and his script got shredded into something that barely resembled his original idea. Having said that, Man On A Ledge’s failure can be attributed to a mistake I see often in the amateur community – a confusing premise. A good premise is clear and strong and obvious to the audience as soon as they see it. A bad premise takes a lot of extra explaining, and often still leaves unanswered questions. I read Man On A Ledge AND watched the trailer and I’m still not a hundred percent on what’s going on. A guy is pretending that he’s going to jump off a building so that his friends can secretly rob the bank across the street? I mean that sorta makes sense, but with all the ways you can rob a bank, is a fake ledge-jumping decoy really the most logical option? If I don’t understand the concept, I’m not going to see the movie. So that’s one of those things where there’s no wiggle room on. This is why you wanna run your concepts by your no-bullshit crew (people who are honest with you and tell you when your stuff sucks). If they’re confused or not impressed, move on to the next idea.

Runner Runner

Projected Box Office: 60-70 million

Actual Box Office (as of October 9, 2013): 9 million

Runner Runner is what I refer to as a middle-of-the-road script. It’s a decent read, it keeps things interesting enough that you turn the pages, but it doesn’t do an inch more. In other words, it’s generic. And to me, generic is the worst crime you can commit as a writer, because it’s the opposite of everything a writer should be: committed, hard-working, always challenging himself, never satisfied. These qualities ensure you’ll keep writing until you’ve got that fresh new concept, that fresh new scene, or that unique character that nobody’s seen before. A driven writer knows when a section of his script is average or derivative and keeps working on it until it pops. Runner Runner is the opposite of that and audiences don’t need an entire movie to see that. They can pick that up by watching the trailer. So when Runner Runner’s trailer displayed 2 minutes of generic characters, lines, and imagery, of course we’re not going to show up and pay ten bucks for it.

Cloud Atlas

Projected Box Office: 80-100 million

Actual Box Office: 27 million

When agents or producers tell you that your 180 page epic sci-fi script doesn’t have a market, and therefore, there’s no point in sending it out, this is what they mean. There may be 2 or 3 directors who could’ve done a better job than the Wachowski Siblings with Cloud Atlas, and it wouldn’t have mattered. It still would’ve made 25-40 million. That’s because serious takes on esoteric science-fiction fare don’t make money. We’ve seen it with movies like The Fountain. We’ve seen it with movies like Solaris (2002). Even Blade Runner didn’t do that well. If you want to survive in sci-fi, you have to go more mainstream. Robots trying to assassinate people. Guys waking up every 8 minutes in a train after it keeps blowing up. Giant Robots battling monsters. And the thing is, you can still explore some dark themes in those scripts. You’re just not being pretentious about it or over-complicating the narrative. It should be noted, though, that you can make your pretentious esoteric sci-fi flicks if they cost very little (like Primer). There IS an audience out there for these films. It’s just not very big.

There’s an old saying in Hollywood that no one sets out to make a bad movie. And, for the most part, I believe that. It’s in everyone’s best interest to make a good movie because it ensures they’ll keep getting work. BUT, I still think there are a lot of lazy people in Hollywood who aren’t trying as hard as they think they are. Being honest with yourselves when something isn’t working and figuring out a solution (particularly at the script stage) can be the difference between a good and a bad movie, or in some cases, stopping a movie that’s going to lose everyone money.

This is your chance to discuss the week’s amateur scripts, offered originally in the Scriptshadow newsletter. The primary goal for this discussion is to find out which script(s) is the best candidate for a future Amateur Friday review. The secondary goal is to keep things positive in the comments with constructive criticism.

Below are the scripts up for review, along with the download links. Want to receive the scripts early? Head over to the Contact page, e-mail us, and “Opt In” to the newsletter.

Happy reading!

TITLE: Noir of the Dead

GENRE: action horror/comedy

LOGLINE: A former gangster must once again take up the gun and unite rival Prohibition enemies in order to fight off marauding, mutant zombies.

WHY YOU SHOULD READ: “I wrote this script with the intention of having fun with some familiar tropes…Prohibition gangsters, zombies, a mad scientist, the lethal femme fatal. The script ended up in a digital sock drawer…until I dusted it off and entered it into the ScreenCraft Horror contest, where it made the finals. My prize was development notes from someone named Pat at LD Entertainment…and I’m actually embarrassed to repeat some of his complements, where the writing was compared to Billy Wilder and I.A.L Diamond…and now my girlfriend thinks I write like Willy Wonka and I’m sure Scriptshadow readers will think I write more like Lester Diamond. But some judges and a studio guy liked it, maybe a few others will too. You never know.

Can we have a word on zombie scripts? The other day I saw my 6 yr old niece playing some zombie game on her kid’s i-pad, and apparently it’s the most popular game. I had an apocalyptic vision of millions of kids growing up already hooked on zombies. Zombies ain’t going anywhere. Disco may be dead, but the undead…well, the undead never die.”

TITLE: Submerged

GENRE: Contained thriller

LOGLINE: Trapped in a shrinking air pocket deep beneath the ocean’s surface, the survivors of a plane crash battle to stay alive long enough for the rescue teams to locate them.

WHY YOU SHOULD READ: “This is my eighth screenplay, all in the action thriller genre. Submerged adheres rigidly to all of the spec script rules laid out on Scriptshadow – it is a low-budget, contained thriller with a marketable concept, set in a unique location, featuring a proactive protagonist who must conquer a potentially fatal flaw to succeed. And it all happens in a reader-friendly 94 pages!”

TITLE: Coin

GENRE: Thriller/Heist

LOGLINE: A brilliant young thief is forced to rob an auction in the heart of Manhattan, but, when the rules change, his mission becomes a life and death struggle to find his tormentor before he kills his mother.

WHY YOU SHOULD READ: “The script was inspired by your French Week review of the Untitled Hlavin project. To its credit, it’s an interesting departure from the normal heist story. Exhibit A. The object being sought is a coin and, although it is valuable, the protagonist stands to make zero dollars for his efforts. Not your standard 80/20 split. Already, things are different. Exhibit B. The protagonist is, for all intents and purposes, retired. Sure, he’s young. But he’s seen the flaw of his ways and changed. Exhibit C. The story is more about the journey than the goal as it explores his life and relationships as he figures out what his next moves will be. He has a good heart and it shows. Together with all of the twists and turns and backstabbing double-crosses, he’s never able to tell who’s with him and who’s not. It all adds up to thrilling adventure that pushes him to the limits of his abilities and wits, climaxing in a thrilling showdown you won’t see coming.”

TITLE: The After-Afterlife

GENRE: Comedy

LOGLINE: Terrified that there may not be life after the afterlife, a group of ghosts must convince the world that ghosts exist by revealing themselves to the crew of a cable ghost show on the night before their haunting place is bulldozed to the ground. It’s something that’s way easier said than done. It is a basic cable show, after all.

WHY YOU SHOULD READ: “In a word: story. This is a story first and foremost. It’s a funny story, but story always, always, always takes precedent over funny. Then, in many words: I wrote with a partner for many years, and we even scored well in a multitude of contests including Nicholl (Semifinals twice) and the Austin Film Festival (Finals). But now I’m trying a few solo scripts, and need to know if I’m good on my own, or if I should beg my partner to take me back.”

TITLE: Shifting.pdf)

GENRE: Supernatural Horror/Drama

LOGLINE: A teenage girl balances high school life with keeping her lycanthropy at bay.

WHY YOU SHOULD READ: “I’ve worked for the city as a 911 call taker for the last, going on seven years. You hear stuff. One minute it’s a guy who robbed the local Best Buy (make that tried) of a PS3 console, tripped and fell in the parking lot, busting his head open in the process — now he’s got a brief hospital visit to look forward to, followed by a slightly longer stint in jail — the next it’s a man playing with his pet puppy, which ended up biting clean through his penis (do. not. ask.), and EMS has to walk him through how to contain the bleeding while his girlfriend laughs uncontrollably in the background.

Not to mention, of course, random conflicts among senior citizens involving tasers.

It can put your mind in a place. Which brings me to “Shifting”. I think I wrote this as a way of staying sane in my most unsanest of professions, but also out of genuine affection for werewolf cinema. Even ‘Bad Moon.'”

Submit Your Script For A Review!: To submit your script for an Amateur Review, send in a PDF of your script, along with the title, genre, logline, and finally, something interesting about yourself and/or your script that you’d like us to post along with the script if it gets reviewed. Use my submission address please: Carsonreeves3@gmail.com. Remember that your script will be posted. If you’re nervous about the effects of a bad review, feel free to use an alias name and/or title. It’s a good idea to resubmit every couple of weeks so your submission stays near the top.

Genre: Sci-Fi/Thriller

Premise: (from writer) When a homicide detective learns that the murderer of a Senator was the victim of a high-tech setup, he then uncovers a conspiracy that makes him question everything he believes in, even himself.

Why You Should Read: (from writer) “In 2003 I had a “concept” for a Sci-Fi movie but had never written a screenplay. My wife saw a news piece for a screenplay community on the Internet, where you could upload your work and get constructive reviews and help. I read the first ten pages of the “Terminator” to get an idea of formatting. Using Word templates and a few reference books, I knocked out the first draft of in a week. The formatting was terrible and the story was littered with mistakes. But I pushed on and learned/developed the craft though constructive feedback and hard work. — My ideas were always a little high concept (and budget) so I began to get interested in short scripts and independent film, to both learn and give me a chance at getting produced. 10 years later I’ve just started a draft of my 19th feature script and finished short script 120. So I guess it’s fair to say I’ve been bitten by the bug of screenwriting. I’ve had short films screened in Cannes, won and placed in contests (thrilled that Kenneth Branagh read and selected one of my scripts). But am I any closer to breaking into the business? Hell no! But I’m enjoying the journey and learning as I go.”

Writer: Sean Ryan

Details: 100 pages (August 7, 2013 draft)

I coulda swore I reviewed this script on the site before. I know I’ve given Sean notes on it. But a search back through the archives shows that it’s never been reviewed. But even if it had, I’m interested to see how my notes and the subsequent drafts Sean’s written have improved the script. Sean’s sent me plenty of updates via e-mail so I know he’s been working on it forever. Which leads us to the “21st draft” reference on the title page. Definitely don’t want to keep that there. Readers have this weird thing where if they see you’re on some really high draft, they’re put off. Therefore, it’s always in your best interest to imply that you’re on your 2nd or 3rd draft. That way, they’re always impressed. “Wow, you pulled this off in 2 drafts?!” Lying is bad. Unless you’re a struggling screenwriter.

Moving on, my big issue with the previous draft of SWAP was that it was too generic. I liked the idea, but I thought Sean was making some very obvious choices. When you have a good idea, especially one like this, which allows for a lot of intricate story directions (literally any character in the story can be anyone else), you have to take advantage of it. Let’s see if Sean’s done his job.

39 year-old Detective Mitch Chance has been assigned to one hell of a weird case. Some dude just shot up the inside of a mall, killing a Senator in the process, but now claims that he didn’t do it. He’s on every security cam in the building, yet he says he has no memory of it happening. And a lie detector test confirms his claim. Somehow, this killer believes he didn’t kill.

While everyone else chalks it up to the dude being crazy-time, Mitch can’t get the case out of his head. And things get weirder when he’s contacted by a mystery man to meet in secret. The man tells him to look deeper into the shooter, implying that he didn’t kill those people. But how can someone who’s been video-taped mowing everyone down with an AK-47 NOT be the killer? It’s impossible! Or is it?

Mitch realizes he’s onto something big when he and his family are attacked, presumably because someone knows he’s digging. Naturally, he starts digging deeper, eventually learning that the government is running a secret program called “SWAP” where they can jump into people’s bodies and control them. This allows them to do things like jump into a terrorist’s body thousands of miles away and have him kill all his terrorists buddies, which sounds good to me. But you get the feeling that the naughty government is now using the technology for much less patriotic purposes.

What follows is a complicated game of chess where we’re never sure who’s who. Who’s in who’s body? Mitch is able to jump into bodies in the government’s secret facility, and the government is able to jump into the bodies of everybody close to Mitch (and even Mitch himself). It starts to get really complicated, as nobody can trust anybody. Will Mitch be able to navigate this puzzle and take down the SWAP program? Or will he be yet another victim?

So, what’s the verdict??

This was a tough call. First of all, I really like Sean. You’re never going to find a nicer, more dedicated writer than him. The problem with that is, since I WANT to like the script so badly, I don’t think my judgment was 100% objective.

I will say, though, without question, this draft was better. One of the things we talk about a lot on this site is “dramatic irony.” Although it’s more complicated than this, it basically means the reader is aware that one character is keeping a secret from the other. SWAP, then, has the potential to be a dramatic irony gold mine, since there are a ton of scenes where WE know a character is hiding inside another character, but the other characters in the scene do not know that. To that end, I thought Sean did a good job. Every scene had that extra layer of deception driving it, which kept things pretty entertaining.

What hurt the read for me, though, was that there was a certain thinness to everything. And I saw this being discussed in the comments the other day – this idea of a “fast read,” and how readers are always looking for “fast reads.” And SWAP was just that. The writing was really sparse (rarely was there a paragraph over two lines long) and therefore really easy to get through (I think I read the script in an hour).

But here’s the thing. There’s such a thing as being TOO fast of a read. Sometimes we need that thick description of a major character (“Tall and blond” isn’t enough). Sometimes we need that dark warehouse described in detail in order to create atmosphere. But more importantly, we need the relationships to be more complex. And I’m not saying it’s easy. This is a thriller. It’s tough to keep the story moving quickly – like all the readers want – yet still explore relationships. But it IS possible. Taken, the prototype for a lightning fast thriller, actually sets up a complicated family dynamic in its first act, with a father trying to reconnect with his daughter amidst his ex-wife re-marrying. I wanted SOME kind of emotional storyline like that to latch onto here.

Personally (and I’m not saying this is everyone), I need to be able to connect with the characters in more than a surface-level way to get involved in the story. And again, Sean doesn’t do a bad job here. Mitch’s daughter is almost killed. We see his desire to keep his family out of harm’s way. But I wanted something specific. Maybe Mitch’s daughter is older (15) and starting to pull away from her father. Or Maybe Mitch and his wife have been having problems and she’s thinking of divorcing him. I just reviewed the new Johnny Depp project, Mortdecai, in my newsletter and that’s exactly what they did. Our main character’s wife was pulling away from him, and you got the feeling that unless he succeeded in his goal, she was going to leave him.

These were the things bouncing around in the back of my head while I was reading SWAP, and when I’m reading a great script, there’s nothing bouncing around in the back of my head. I’m just enjoying the story.

I think Sean’s done a good job mastering the structural component of screenwriting. He’s got a good feel for plotting and keeping the story moving. But if screenwriting prowess is measured on a 1-10 scale, I think mastering this aspect only gets you to level 5 or 6. The next step – that leap up to 7 and 8 – requires you to master character development and character relationship development. Learning how to not only build that into your story, but do so in a way that doesn’t slow the story down, is what gets you to a place where agents and producers start noticing you. So this one flirted with a “worth the read,” but didn’t quite make it there. Still, I hope to see more stuff from Sean in the future. But only those 2nd and 3rd drafts. :)

Script link: SWAP

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: I looked back at my notes for SWAP (when I did a consultation with Sean) and saw this line: “Remember, for every question that’s answered, a new one should be posed.” – I want to commend Sean for listening to that advice. This new draft did a better job of replacing answered questions with new questions. But I bring this up because I’ve read a lot of scripts lately that DIDN’T do this. If you’re going to give us the answer to one of your key mysteries, ALWAYS pose a new one. This way, you’re always dangling a carrot in front of the reader, giving him a reason to keep walking. The second there’s no carrot, is the second we turn around and head back home.

I love seeing movies break out and do a lot better than they’re supposed to. Hollywood likes to think that they have it all figured out. They’ve got formulas. They’ve got formulas FOR their formulas. They can give you opening weekend numbers for a film six months before they’ve even shot it. As the industry continues to move closer to the way the rest of American businesses are run, a specific understanding of how each product is going to do is vital to their business plan. But every once in awhile, something still surprises them. And it absolutely KILLS them. Because even if a film does ten times better than they think it will, somebody fucked up – why didn’t they know that would happen?

This is why I love trying to figure out why a movie broke out. Obviously, directing and marketing and star power are going to be huge factors in any movie’s success. But it always comes back to the screenplay. Every trailer, every poster, every marketing campaign, every great acting performance – all of those things stem from the screenplay. And when it comes to the screenplay, there are two things determining a film’s success at the box office: The first is concept. You gotta give us an idea that will make us come to see the film. And the second is execution. This will determine if people come back again and if they tell their friends to see it.

Now what surprised me as I looked back at the box office over the last couple of years was that there was no out-of-nowhere mega breakout hit. There was no Paranormal Activity or The Blair Witch. No My Big Fat Greek Wedding or Slumdog Millionaire. So maybe the studios ARE getting better at knowing what works and what doesn’t (or maybe it means they’re not taking enough chances). However, there were plenty of movies that over-performed. Here are five of them, and what they can teach us about screenwriting.

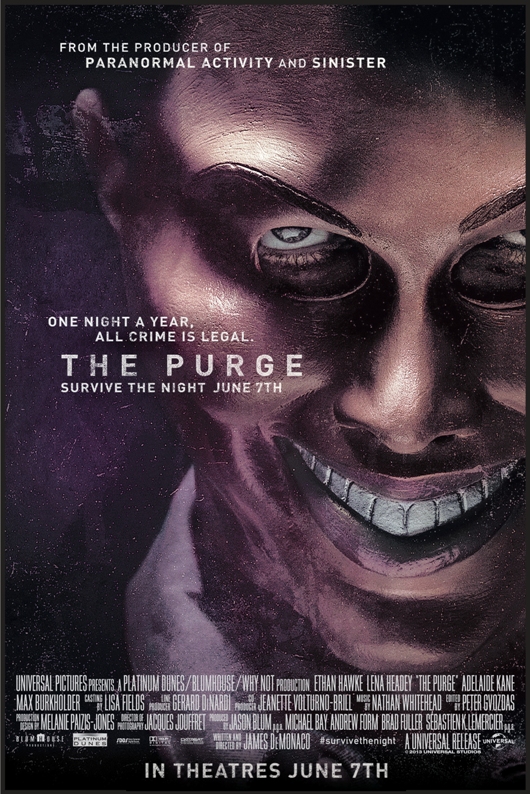

The Purge

Projected box office: 20-25 mil

Actual box office: 65 mil

What The Purge teaches us is that the clever high concept idea will never die. If you can come up with a cool exciting premise, somebody will buy your screenplay, it will be turned into a movie, and that movie will do well. The Purge asks the question, “What if for one night every year, there were no laws? You could commit any crime you wanted?” That’s why people went to see this movie, because of its concept. To demonstrate the value of this, consider a near replica film that came out later in the summer, You’re Next. Both films were about a family stuck in a house being hunted by people with masks. But You’re Next didn’t even come close to doing The Purge’s box office, despite being a better movie. Why? Because it didn’t have that catchy concept. It’s why I beg and plead with you guys that before you spend the next 6 months to 2 years writing a screenplay, make sure your concept is something people will be excited to see. Not “want to see.” But BE EXCITED to see.

We’re The Millers

Projected box office: 60 mil

Actual box office: 142 mil

I reviewed this script way back in the day and wasn’t impressed. It felt flat and generic. However, I always thought the idea was good, so I’m not surprised people showed up on opening weekend. But the reason this movie went from a solid opening weekend to nearly 150 million dollars was the script, the script, the script. The script REALLY improved, becoming less about random funny jokes, and more about the relationships and the growth of the characters. When you write a comedy, you want to focus on change. You want all of the characters to grow and become better people by the end of the story. Amateur screenwriters think this is cliché and cheesy and avoid it. Professional screenwriters know it’s the trick to make the movie feel complete, feel like it was worth the ride. If the people we’re watching can change, we think we can change. Which makes us feel good, which makes us talk about the movie fondly afterwards. Which makes our friends want to see it. We’re The Millers buttered itself up in heart. It was about a non-family becoming a real family. It wasn’t just funny. It made you feel good.

The Hunger Games

Projected box office: 125-175 mil

Actual box office: 408 mil

The Hunger Games might seem an odd movie to include on this list, but not in any producer’s wildest dreams did they think this film would hit 400 million. Many people chalk this up to the YA novel phenomenon (which has only begun to hit us, for better or worse) but don’t fool yourselves. Hopeful YA books-turned-movies Beautiful Creatures and The Host couldn’t crack 30 million. So Hunger Games was by no means a sure thing. To me, there were a couple of key ingredients to the film’s success. First, IRONY. With film, the right ironic angle can be like audience crack. And here, it’s as ironic as irony gets. Kids fighting in a game to kill each other. Kids aren’t supposed to fight to the death, so we’re intrinsically drawn to that idea. But I think a lesser known ingredient to the film’s success was the simplicity of Hunger’s idea. Remember that in this day and age, you gotta be able to sell a movie to an audience within seconds, which is why so much emphasis is put on the logline. If you can’t explain your screenplay in one simple sentence, how are producers and studios going to explain it on a billboard? Or in a 30 second TV spot? All you need to know about The Hunger Games is that a game is being held where kids are trying to kill each other. You immediately understand the film. I must’ve seen that Beautiful Creatures trailer 7-8 times and I STILL can’t tell you what that’s about. It’s too confusing. The Host was a little clearer, but not really. This girl is taken over by an alien host. But why? And what happens then? It doesn’t sell itself easily. Back to the crème de la crème of YA adaptations, Twilight – a girl falls in love with a vampire. Simple and to the point. I’m not saying that every single script you write needs to be boiled down to one easy sentence. I’m saying that if you’re writing the kinds of movies you hope to sell to a mass audience, they do.

Argo

Projected box office: 60-70 million

Actual box office: 136 million

Argo is one of wackier studio movies I’ve seen do well. Its success can be broken down into two key categories. First, it’s a combination of two subject matters that aren’t supposed to go together. Making a Hollywood movie meets saving Americans in Iran. Those two worlds don’t mesh. That intrigued people enough to show up. But Argo’s box office came mainly from word-of-mouth. In other words, it succeeded because of its well-executed story. So you might be surprised to know that the film has the most traditional structure of all the films on this list, and maybe even the top 20 films of 2012. Argo is a case study in GSU. You have the goal – go save the Americans in Iran. You have the stakes – if they get caught, they’ll be held hostage or worse. You have the urgency – they only have permission to be in Iran for a few days. So they have to do this fast. I don’t mean to promote my book here or anything, but this is about as clean a setup for a story as there is. GSU, or traditional structure, may have been used by thousands of films throughout history, but THAT’S BECAUSE IT WORKS. It’s the best way to tell a story, hands down.

Silver Linings Playbook

Projected box office: 65 mil

Actual box office: 132 mil

Got to give it to David O. Russel. He took two films with indie premises (The Fighter and Silver Linings) and turned them into big box office hits. That isn’t easy to do. While there’s no doubt Silver Linings Playbook benefited from the casting of two hot actors (Bradley Cooper and Jennifer Laurence), that’s not the reason it made so much money. Cooper’s “The Place Beyond The Pines” didn’t make any money. Nor did his “The Words.” And I’m still looking for a single person who saw Jennifer Lawrence’s “House At The End Of The Street.” There’s a lot more at play here. In fact, Silver Linings does a couple of really smart things. First, it takes a genre and flips it on its head. A romantic comedy between two depressed crazy people. This is one of the easiest ways to make your spec stand out, by giving us a new take on a genre. Never forget that. Second, it gives us two really interesting characters. A bi-polar OCD semi-autistic guy with anger issues, and a clinically depressed slutty neurotic girl. We don’t ever get to see those characters on the big screen, and we definitely don’t get to see them going after each other in a romantic comedy. So that was new and exciting. But what I loved about Silver Linings was that it knew it needed boundaries. It knew that crazy doesn’t work without a focused narrative. Cooper’s character’s goal to get his ex-wife back coupled with the dance competition narrative is what allowed these characters to be so nuts without the film running off the rails.

And so there you have it. My belief on why those movies did well. With that said, it’s also important to admit when you don’t know jack shit. And there were a few movies that succeeded over the last couple of years that have straight up baffled me. Like Lincoln. That film made 180 million dollars. I didn’t think it’d break the million dollar mark. The script is all talk talk talk. Zero action. The trailer made me think of something I was forced to watch during History class. I know Spielberg directed it and Daniel Day Lewis acted in it, but the similar-in-tone (and theme) Amistad didn’t do any business, and while Day Lewis is an amazing actor, he’s hardly box office gold. So I have zero idea how that movie did well and am open to suggestions. I’m surprised “42” made 95 million. That film looked really generic (though they did market it well). Didn’t think Ted would get anywhere near 220 million. Uber-generic Safe House’s success still shocks me. So yeah, I still have questions. But that’s what makes analyzing these movies and their success so fun.