Search Results for: F word

Amateur Friday Submission Process: To submit your script for an Amateur Review, send in a PDF of your script, a PDF of the first ten pages of your script, your title, genre, logline, and finally, why I should read your script. Use my submission address please: Carsonreeves3@gmail.com. Your script and “first ten” will be posted. If you’re nervous about the effect of a bad review, feel free to use an alias name and/or title. It’s a good idea to resubmit every couple of weeks so your submission stays near the top.

Genre: Drama

Premise: (from writer) A man embarks on a relationship with a 9/11 widow after claiming to have lost his brother in the attacks.

Writer: Edward Ruggiero

Details: 107 pages.

I actually read Nine-Twelve awhile ago and always wanted to review it for Amateur Friday. So when the writer, Ed Ruggiero, sent me a new draft, I thought, “Perfect.” Don’t worry. That doesn’t mean I’m not checking all the submissions you guys are sending me, just that I don’t like them! No, I’m kidding. But I do want you to remember there are a lot of submissions. If your concept is just “okay” or “decent,” it’s probably not going to be picked. I mean sure, it might be amazing, but I could use that same logic for each of the hundreds of other “okay” or “decent” concepts. So why should I pick yours over theirs? You know? I’d rather pick a concept that gets my juices flowing – that has a little more POP.

Artie Grossman is in his late 30s and doesn’t have much to show for it. He has some inheritance money, which he’s learned to squeeze every penny out of, and when he’s not taking money out of his dead parents’ bank account, he’s pulling charity scams on local businesses. Oh yeah, Artie’s not a good person. He’s pretty much a piece of shit. He’s negative. He’s dishonest. And as we’ve already established, he’s a thief. Yup, a total winner.

But not everything about Artie is pathetic. He actually takes care of his dysfunctional brother, Dicky, who’s so terrified of the real world that he rarey goes outside. Artie’s working with Dicky a day at a time to get him back into society. So we got a pathetic asshole thief and a guy who’s afraid to leave his apartment. Talk about a gene pool. I’m not sure even Axe Body Spray could make these two attractive.

That is unless they LIE. And Artie is one hell of a liar. After spotting a homely but beautiful woman on the subway, he follows her across the city into a random support group, a support group he soon realizes is for peole who lost family members in the 9/11 attacks. Spurred on by this woman’s unique energy, he joins in, and quickly finds himself recounting a story about how his brother died in the attacks. It’s moving and powerful and total horse shit. But the woman, Kerry, buys into it, and afterwards the two recount their 9/11 memories with one another.

Turns out Kerry lost her husband in the attacks, and hasn’t been on a date since! She just can’t let go. Particularly because she had a chance to answer her husband’s final phone call, but carelessly sent it to voicemail, figuring she’d talk to him later. She was a different person back then. Not a very good one. And she’s paid the price for it ever since.

However now, with Artie in the picture, she gets out there and starts to feel good again, which you’d think would make her frustrated mother happy. But it turns out her mother doesn’t trust this new guy. She feels there’s something suspicious about him. A mother’s intuition is always right! But Kerry’s too wrapped up in remembering what it’s like to feel happy again so she ignores all the warning signs (number 1 of which is – don’t date guys without jobs).

What starts out as just a meaningless little jaunt becomes serious, and before you know it, Artie is all in, which is strange. He’s never been all-in before. And when you’re all in, all your secrets have to come out. You can try to hide them, but your significant other’s going to find out sooner or later. So what’s Artie’s solution to this? To run away with Kerry. Go somewhere as far away as possible. In other words, avoid the problem. But this appears to be one of those problems that’s never going to go away.

Dramatic Irony.

We know something about our hero that the romantic lead does not. That he’s lying to her about the worst thing imaginable. It’s dispicable. It’s unthinkable. And it’s great writing. Because this entire relationship is built on a lie that we’re aware of, a lie that we know, if told, will destroy the relationship, we want to stick around and see what happens when Kerry finds out. Dramatic irony creates suspense. It creates anticipation. It keeps our ass in the seats.

The question is, can one instance of dramatic irony carry an entire film? Reading this a second time, I found myself impatient, particularly during the second act. It felt like not enough was going on, and I realized just how much the script was leaning on that dramatic irony. It was the ONLY thing driving the story forward, and the longer I read, the more I realized it wasn’t enough.

In contrast, let’s look at Good Will Hunting. We have the same thing going on in that story. Will is lying to Skylar. To impress her, he tells her he’s well-off and has a huge family, when he’s actually poor and an orphan. There’s not as much at stake with the lie as in Nine-Twelve, but you’ll notice that that’s only one part of the story. We also have Will’s relationship with Sean (the therapist) that needs to get resolved, his inner conflict, his future as a math genius, his issues with Ben Affleck’s character. There are more developments in that screenplay, more subplots, and therefore the entire movie doesn’t feel like it’s resting on a single wooden beam.

Another thing I want to talk about here is rewriting. Now, to be honest, I don’t remember the notes I gave Ed on this script, so I’m not saying he’s guilty of this. But when he said he had a new draft, I know I was expecting…I don’t know, just more changes. It feels here like just a few scenes were changed and another couple added.

It’s something I’ve noticed a lot of lately as I’m reading more and more rewrites. Not much has been rewritten! Changing a few scenes here and there isn’t a rewrite. A rewrite may entail redeveloping the theme, eliminating or combining characters, adding new subplots, eliminating entire subplots. coming into the story 30 pages later, changing the setting so it better matches your concept, changing your character’s fatal flaw. If all you’re doing in a rewrite is adding or taking away scenes, you’re probably not doing enough (unless it’s one of your final drafts).

Having said that, there’s something about this script that got to me. I like the way Ruggiero writes. He has a unique point of view. I love how he’s not afraid to make his hero dark. I understand that that’s going to turn some people off, but while I didn’t like what Artie was doing, he did keep me interested. I wanted to see if he was going to change or not. If he was gong to move on from this disgusting person.

I also liked the touch of humor. There was something funny about Artie. I can imagine a young Bill Murray absolutely killing this role (who *is* the next Bill Murray by the way). So I guess my final suggestion would be to inject this script with MORE STUFF. In the meantime, the voice is unique enough and the writing good enough that it warrants a read. But I still feel like something’s been left on the table in this rewrite.

Script link: Nine-Twelve

What I learned: What I’m looking for in a concept breaks down to three things. The first is a high concept (i.e. Time travel, aliens, monsters – any big idea combined with a unique situation). The second is something with some clear conflict. Two warring families is more interesting to me, for example, than a generic guy trying to find love. The third and final one is irony. If there’s an ironic component to the concept, I get excited. Look at the irony in this logline. A man pretending to have lost someone in 9/11 starts a realtionship with a 9/11 widow. That same concept isn’t nearly as compelling if, say, a man who just lost his arm starts a relationship with a 9/11 widow. There’s no irony there!

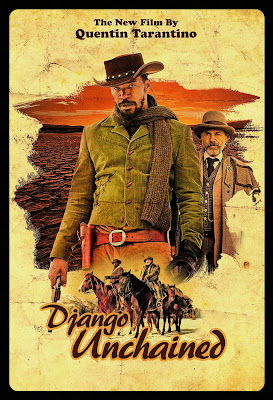

Genre: Tarantino

Premise: (from IMDB) With the help of his mentor, a slave-turned-bounty hunter sets out to rescue his wife from a brutal Mississippi plantation owner.

About: This is the next Quentin Tarantino film, coming out Dec. 25. Django Unchained stars Jaime Foxx as Django, Christoph Waltz as Dr. Schultz, Leonardo DiCaprio as Calvin Candie, and Samuel Jackson in the fearsome role of Candie’s 2nd hand man, Stephen. QT has wanted to do something with slavery for awhile, but not some big dramatic “issues” movie. He wanted to do more of a genre film. Hence, we got Django Unchained!

Writer: Quentin Tarantino

Details: 167 pages, April 26th, 2011 draft

These days, much of the time, I read scripts with a workman-like focus. That’s not to say I don’t enjoy reading. I love breaking down screenplays. But there’s always another script to read, another friend or consult or review to get to. Which means I have to stay focused, I have to get everything done.

Rarely do I read a script where I turn off the script analysis side of my brain and just enjoy the story. It happens two or three times a year. With Django, it actually went beyond that. Halfway through the script, I was so pulled in, I canceled everything and made a night of the second half of Django. I cooked dinner. I opened a nice bottle of wine. I pushed back deep into the crevice of my couch. I ate, drank and read.

Okay okay, so I didn’t actually cook anything. It was a lean cuisine meal. And I popped open a bottle of coke, not wine. I hate wine. But the point is, Django Unchained was that rare reading experience where the rest of the world disappeared and I just found myself transported into another universe.

And you know what? I’m not sure why the hell this thing worked so well. It was 168 pages. There was usually more description than was needed. Many scenes went on for ten pages or longer. BUT, Tarantino found a way to make it work. What that way is, I can only guess. Maybe it’s his voice? The way he tells stories makes all these no-nos become hell-yeahs. And that’s not to say he bucks all convention. There’s plenty of traditional storytelling going on here. It’s just presented in a way we’ve never quite seen before.

Django’s a slave who’s recently been purchased by a plantation owner. Part of a bigger group, the slaves are being transported to the new owner’s farm. There are a lot of nasty motherfuckers in this screenplay, guys way worse than the brothers pulling Django along this evening, but these men are still the kind that need a good bullet in the head to remind them of just how shitty they are.

Enter an upper-class German gentleman who appears out of the woods like a ghost. Dr. King Schultz is as smart as they come and as polite as you’ll ever see, and he’d like to ask these brothers which slave here goes by the name of “Django.” Predictably irritated, the brothers tell him to take a hike or take some lead. While respectful, Dr. Schultz doesn’t like to be told what he can and cannot do. So he smokes one of the brothers, disables the other, and makes Django a free man.

You see, Dr. Schultz is a bounty hunter. He gets paid lots of dough for the carcasses of wanted men. And it appears he’s looking for Django’s former owners, three rusty no-good brothers (there are lots of siblings in Django Unchained) who’ve changed their names and are hiding out on some plantation. Dr. Schultz will pay Django a nice sum if he can identify these men so he can kill them.

Now these men also happen to be the men who raped and branded his wife, Broomhilda. So yeah, Django knows who they are all right. He’ll help the strange German. Plus, with the money he earns, he can go off and search for his wife, who’s since been sold off to another owner. Django doesn’t know who or where, but Schultz tells him he’ll help him find her.

Away the two go, infiltrating the plantation where the brothers are hiding out, and Django gets some sweet revenge on his former slavers. The two are such a great team that Schultz recommends they extend their contract and start making some real money upgrading to the big names, the kind of names that need two people to take them down. Besides, he persuades Django, if they’re going to save Broomhilda, Django has to be in tip top shape.

So the two go off, hunting wanted men, and in their downtime, Schultz teaches Django how to read and shoot. Eventually, Django becomes the most educated badass cowboy around. And it’s a sight to see. And a sight people aren’t used to seeing. When townsfolk observe an educated free black man riding into their town on a horse, they think it must be some kind of joke. And at first, Django feels like a joke. But after awhile, he starts seeing himself the way Schultz does, as a man who deserves to be respected.

Once they’re ready, the two come up with a plan to save Broomhilda. Unfortunately, Broomhilda is being held by one of the nastiest plantation owners in all the state, a detestable villanous soul named Calvin Candie, and Calvin Candie won’t just see anybody. If you want his attention, you have to pony up. Which means Schultz and Django must pretend to be looking for a fighter in one of Calvin’s favorite hobbies – Mandingo fighting. Basically, these are slaves forced to fight other slaves for white men’s entertainment.

In their scam, Schultz will play the rich interested party, and Django will play the “Mandingo expert” he’s hired in order to find the best fighter. Calvin could give two shits about the two until Scultz says the magical words, “Twelve thousand dollars.” Now Calvin’s ready to talk, and he decides to take them back to his plantation where the talking acoustics are a little nicer, the amusement park-esque estate known as “Candyland.”

While at Candyland, the two covertly scope out Broomhilda’s whereabouts, except that Calvin’s number 2 guy, groundskeeper Stephen (who’s, surprisingly enough, Calvin’s slave), suspects something is amiss with these men, and starts to do some digging. It doesn’t take him long to figure out their intentions, intentions that have nothing to do with buying a Mandingo. He lets his boss know, and for the first time since we’ve met Django and Shultz, the tables have turned. They’re not in control of the situation anymore. Once that happens, our dynamic duo is in major trouble. And it’s looking unlikely that they’ll find a way out of it.

Let me begin by saying that a big reason this script is so awesome is because of the GOALS and the STAKES. There’s always a goal pushing the story forward, which is extremely important in any screenplay but especially a 168 page screenplay. If your characters don’t have something important they’re going after, a solid GOAL, then your story’s going to wander around aimlessly until it stumbles onto a highway and gets plastered by a semi. A gas tanker semi. A gas tanker semi that explodes and starts a forest fire.

The first goal is Schultz’s goal of needing to find these brothers. Once that goal’s taken care of, the true goal that’s driving the story takes center stage – Django needs to find and save his wife. But, you’ll notice that even when we’re not focused directly on that, we have little goals we’re focusing on. It may be to kill one of the many wanted men they’re hunting. It may be to learn to read or fight or handle a gun, so that Django can be equipped for his final showdown. QT makes sure that we’re always driving towards something here, and he does it with goals. Goals that have stakes attached to them. How can the stakes be any higher than your wife’s safety and freedom?

But that’s not the only reason. Outside of Mike Judge, I don’t know any writer who can make his characters come alive on the page better than Tarantino. He just has this knack for developing unique memorable people. I can go through 5-6 scripts in a row and not read one memorable character. This script has like two dozen of them. It’s amazing. Sometimes it’s because he subverts expectations – Dr. Schultz is a German in an unfamiliar land who’s as dangerous as fuck yet always the most polite man in the room. Sometimes it’s through irony – A slave bounty hunter hunting the very white people who enslaved him. And sometimes it’s just a name – Calvin Candie. I mean how perfect a name is that? How are you going to forget that character?

I tell writers NEVER to overpopulate their screenplays with large character counts because we’ll forget half the characters and never know what’s going on. But when you can make each character this memorable? This unique? You can write however many damn characters you please.

And the dialogue here. I can’t even tell you why it’s so awesome because I don’t know. There are certain elements of dialogue you can’t teach and QT is one of the lucky bastards who possesses that unteachable quality. But I will tell you this, and it’s something I’ve become more and more aware of in subsequent Tarantino movie viewings. He depends on a particular tool to make his scenes awesome, and it’s the main reason why he can write such long scenes and get away with it.

Basically, Tarantino hints that something bad/crazy/unpredictable is going to happen at the end of the scene, and then he takes his time building up to that moment. Because we know that explosion is coming at the end, we’re willing to sit around for six, eight, ten pages until we get there. The anticipation eats at us, so we’re biting our nails, eager to see what’s going to happen. In these cases, the slowness of the scene actually works for the story because it deprives us of what we want most, that climax.

For example, there’s a scene in the second act where the young man who’s bought Broomhilda and since fallen in love with her, takes her out for a night on the town. He unfortunately walks into one of Calvin Candie’s establishments and before you know it, Candie himself has invited him over to his table to play poker with the big boys. Broomhilda knows something’s not right, but the poor soul is too flattered to listen to her. This scene goes on and on and we see that Candie is becoming more and more sinister, and we just know this isn’t going to end well. We know something terrible is going to happen. So of course, we’re on the edge of our seats dying to see in what terrible way it will end.

Tarantino also did this, most famously, in the opening “Milk Scene” of Inglorious Basterds. A German Commander shows up at a farm house looking for fugitive jews, and we just know this isn’t going to end well. That’s why the German commander can ask for something as unexciting as a glass of milk. That’s why he can talk about mundane things for minutes on end. Because we know this isn’t going to end well, yet we’re dying to see how it does end. Go through Django Unchained again and you’ll see that there are LOTS of these scenes, and one of the biggest tricks Tarantino has in his toolbox. He keeps going back to it, and it works every time.

But what I think really separates Tarantino from everyone else is that you never quite know where he’s going to go. You can predict most movies out there down to the minute. But with QT, you can’t. And it’s because he already knows where you think he’s going to go, so he purposely goes somewhere else. Take the opening scene, where we see a polite white man being kind and cordial to a slave. Not prepared for that. Or when we see that Calvin Candie takes his orders from a black man, his slave, Stephen. Or how when Broomhilda is first purchased, she’s actually purchased by a shy young white man who quickly falls in love with her and treats her kindly. I was always trying to predict where Tarantino would go next, and I was usually wrong. And even better, the choice he ended up going with always ended up in a better scene.

My complaints are minimal. There was only one area of the script that felt lazy. (spoiler) Late in the third act, Django’s life is spared because, apparently, he’ll experience a much worse death “in the mines.” This allows him to be transferred off the plantation, which of course allows him to trick his transporters and go back to save Broomhilda. Come on. No way the Candie family doesn’t torture and kill him right there. No way they let him go off to the mines. So I was disappointed by that because it felt like a cheap way to give Django his big climax. With that said, the big climax was phenomenal. Average Joe Writer would have had Django go in there Die Hard style. QT took a slower more practical approach, and created a much better finale because of it.

So you know what? I can’t believe I’m doing this since I haven’t done it in two years before a month ago, but I’m giving another GENIUS rating. This script is freaking amazing. It really is. I don’t know if the Academy knows what to do with a movie like this, but if we’re talking writing alone, this script should win the Oscar. And, heck, it should win for best film too.

What I learned: Always look for ironic moments in your screenplay. Audiences LOVE irony. Django, a slave, must play the role of a slave driver near the end of the film. He must treat other slaves like they’re dirt. He must talk to them like they’re dirt. It’s tough to watch but also fascinating, since he himself was, of course, a slave a short time ago.

Genre: Drama

Premise: When a large natural gas corporation comes into a small town to buy up its natural gas deposits, a few resistant residents make the reps pursuit a living hell.

About: This is the script that Matt Damon and longtime “The Office” co-star, John Krasinski, wrote together. This would be the first script of Damon’s since Good Will Hunting. The film has been shot and I believe is coming out later this year.

Writers: Matt Damon and John Krasinski

Details: 113 pages – undated

Ben.

And Matt.

And Matt. And Ben.

And John?

From The Office?

Wait a minute. What’s going on here? A love triangle?

Alas, it seems the most famous bromance of the last 15 years is officially kaput. Matt has moved on to someone younger and prettier. Not sure how Ben feels about this, but maybe making the dark and brooding Argo was his way of dealing with the pain.

I’ll be honest, when I heard about Promised Land, I was worried for a couple of reasons. First off, two actors writing a script? I mean, I don’t want to stereotype or anything, but what do actors know about writing? Is that any different from Aaron Sorkin saying, “I’m going to go star in my own movie?” Even if Damon had written a script before, he certainly doesn’t have the time today that he did before Good Will Hunting. And who’s to say Krasinski can write? Why do all of these actors all of a sudden think they’re Ernest Hemingway?

And then there was the whole political thing. Damon’s not shy about voicing his political views, and I’d been told this script was a political statement about something called “Fracking.” Ugh, so now I was being preached to by an actor about his political stance on something that sounded like a bad debate topic? Kill me now.

And then I read Promised Land. And I really fracking liked it.

Closing in on 40, Steve Landsman is ready to take that big leap in his career – the one that comes with the free car, the top level medical benefits, and the bank-busting salary. He’s going to be a vice-president in one of the biggest natural gas companies in the world. All he’s gotta do is close this one last town, McKinley, NY, which should be as easy as the drive down from Manhattan.

For a little background, these natural gas companies are trying to pick up the ball that the oil companies dropped. We’re so dependent on oil-rich countries, many of which drive up the prices cause they hate us so much, and yet we have our own huge energy supply right here in our own back yard – natural gas!

This gas is buried deep in deposits all over North America, and all it takes to extract it are these big wells that the natural gas companies build. Problem is, most of the land where you find these deposits is privately owned, which means you have to pay the owners lots of money to allow you to drill on their land. Which usually isn’t a problem. Throw a million bucks at Honey Boo Boo and Co. and chances are they’re going to help you build the drill themselves. Assuming they don’t eat it first.

That is until McKinley, New York. You see, Steve and his partner, 55 year old Sue Thomason, are thrown a curve ball when one of the local science teachers, a man who used to teach at M.I.T., starts educating the townspeople on the dangers of “fracking.” It turns out that the side effects include gas-tainted drinking water, to the point where you can light an icy glass of H2O on fire! Escaped gas can also end up killing farmland and animals. You can say the word “natural,” all you want. But it’s still gas.

To make things worse, an environmentalist named Dustin moves into town representing a group called “Athena.” It turns out the science teacher spiel was only the tip of the iceberg. Dustin starts giving the town a full-on crash course in the harms of fracking. All of a sudden, money doesn’t seem so important to these folks anymore.

Back at headquarters, the company starts worrying that Steve isn’t up to the task, and considers sending in a clean-up team. Knowing that would be the end of any vice-presidential standing in the company, Steve refuses the help and ensures HQ that he can get this done. However, he has a big fight ahead of him, as it seems like with every passing hour, the town is less and less interested in buying what it is Steve’s selling.

Promised Land possesses some good old-fashioned storytelling in its bones. I loved that even though this was a “small” “independent” project, it still relied on tried and true storytelling tools, particularly GSU. The goal was to make the deal with the town’s residents. The stakes were Steve’s promotion (and potentially losing his job). The urgency was the town vote coming up. It just goes to show that simple storytelling techniques can work magic when integrated naturally.

I’ve also found that these “big city know-it-alls” vs. “small town hicks” storylines usually work. The conflict is already built into the situation. It’s a very familiar conflict at that, so it doesn’t take much for an audience to get invested. And what I liked about Promised Land was that it put you inside the shoes of the “bad guy” during that situation. That’s not easy to do because it’s hard to like the bad guy. What I think made it work though is that Steve believed he was doing good. He’s making these people rich. When he realizes maybe that’s not the best thing for them in the long run, that’s when he starts questioning himself, resulting in some inner conflict he must deal with. Any time your character has to battle with something inside himself, you’ve probably got yourself an interesting character. In all the bad scripts I read, the characters are usually too simple and have nothing going on inside. Not every hero will be struggling with something inside, but if it works for your story, I’d suggest doing it.

The script also introduced new plotlines right when it needed to. One of the common problems with amateur scripts is that they run out of story somewhere in the second act. Introducing new developments is a great way to keep the second act alive. So with Promised Land, the key development was the introduction of Dustin. Now, instead of just having to worry about the people of the town, Steve had to worry about this whole other organization, making his job even more difficult. And the way Dustin weaved his way into the very fabric of the town, even going so far as to steal Steve’s girl, made him a great bad guy.

Although I’m not going to spoil it here, I also loved the twist ending, which I didn’t see coming at all. Twist endings in scripts that don’t usually have twist endings are often the best kind, because you’re so not expecting them at all. I mean we’re not talking a Sixth Sense twist level here. But it was still a nice surprise.

I don’t have many complaints about Promised Land. I thought the love story between Steve and Alice could’ve been better handled. It felt like the writers weren’t sure where to go with it. And I thought they could’ve done more with the science teacher, Yates. It’s such a great surprise when they find out he’s some legendary professor teaching high school science here for fun. But then he sort of fades into the background, allowing Dustin to take center stage. Yates never got his moment.

I admit, going into this I expected some pretentious self-important story about the dangers of fracking. Instead I got an accessible entertaining story that nailed exactly what it was trying to do.

What I learned: Remember, if you have a main character who’s tough to like, introduce an oppositional character who we hate even more. We’ll like our tough-to-like character if only to see him topple this annoying asshole. This was the role that Dustin played in the story.

I recently caused a minor fracas by suggesting that screenwriters aren’t “writers,” per se, but rather “storytellers,” and that if you want to become a successful screenwriter, your focus should be on telling stories rather than writing. I’m afraid that some of you took me a little too literally and assumed I meant that there’s no actual “writing” involved in screenwriting.

Writing is, of course, an essential part of telling any story on the page. If I write, “Jason, bloodied and wheezing, stumbles through the airplane wreckage, blinded by the smoke,” that’s a hell of a lot more descriptive and exciting than “Jason walks through what remains of the airplane.” To that end, writing is essential. It’s our job to pull a reader into our universe, and how we weave words together to create images and moments is a large part of what makes that process successful.

However, here’s the rub. Unless you’ve created an interesting enough situation to write about in the first place, it won’t matter how well you’ve described that moment, because we’re already bored. And that’s what I mean by “storytelling.” One must create a series of compelling dramatic situations that pull a reader in for the writing itself to matter.

So to help clarify this, here is how I define writing and storytelling and how they relate to screenwriting. Because this is my own theory, I’m not saying these are universal definitions, only definitions to help explain the points I’m making in the article.

Writing – When I refer to “writing,” I mean the way in which everything in the story is described, the way in which the picture is painted. While important, you can give me the greatest description ever of a character, the greatest description ever of that character’s house, the greatest description ever of the way he goes about his nightly routine, and the greatest description ever of a car chase he gets into later…and I can still be bored out of my mind because you haven’t preceded any of these things with a story I care about.

Storytelling – “Storytelling,” on the other hand, is the inclusion of goals and mysteries that create enough conflict, drama, and suspense to pull an audience in and make them care about what they’re watching. For example, that immaculately described car chase above is boring unless, say, the character driving has 10 minutes left to get across town and save his daughter, with the cops, the mob, and the government trying to stop him.

So how does one “tell a story?” What’s the secret to storytelling? Well, I feel storytelling can be broken down into a couple of simple components. The first is G.O.C. (Goals, obstacles and conflict). In most stories, you have a character goal – a hero who’s trying to achieve something. In order to make their pursuit interesting, you must throw obstacles at them, things that get in the way of them achieving their goal. Naturally, because obstacles prevent our hero from doing what he wants, conflict emerges, and conflict is what leads to entertainment, since it’s always interesting to see how the conflict will be resolved. If a character wants something and gets it without having to work for it, there’s a good chance your story (or at least that part of your story) is boring. John McClane’s goal is to save his wife, but the terrorists in the building provide obstacles to doing so, which creates conflict.

The other major component of storytelling is mystery. If you don’t start with a character who has a goal, you should be working to create a mystery. “Lost” built an entire show around this. From the “Others” to the “Hatch” to the “numbers entry.” We kept watching that show because we wanted answers to those mysteries. Note, however, that mysteries always eventually lead to character goals, since sooner or later a character will be tasked with figuring out that mystery (their goal). “The Ring” is a good example. A mystery is created with this video tape which kills people in 7 days. Naomi Watts’ character, then, has the goal of finding out the origins of the tape, and seeing if she can stop it from killing people.

A writer’s mastery of these two components, the goal and the mystery, are often what defines him/her as a good storyteller and determines whether their screenplays will be any good.

What I often run into on the amateur level is the opposite. I read tons of scripts where writers put all their efforts into immaculately describing their worlds, their characters, their scenes, and everything involved in painting the picture for the reader, but without any conflict or drama or suspense. It’s the kind of stuff that makes you go, “This person is a great writer!!” But in the end, there’s no immediate goal, there’s no compelling mystery. So it’s just boring shit happening. Really well described boring shit happening, but boring shit happening nonetheless. I know a lot of writers send their scripts out and get this recurring note back: “We loved the writing but the script wasn’t for us.” It confuses the hell out of the writer. “If the writing is great,” they ask, “Why the hell wouldn’t the script be for them??” It’s because your story is boring as hell! There’s not enough storytelling!

What you must do to prevent this is make sure you’re storytelling on three different levels: on the concept level, the sequence level, and the scene level. What I mean by this is that your overall concept must have a story built into it, each sequence in your script must have a story built into it, and your scenes themselves must have stories built into them. The second you’re not telling a story on one of these three levels, you’re just writing. You’re describing shit or recounting shit or laying out shit. You’re not storytelling. Let’s take a closer look at these three levels using the film, “Aliens,” as an example.

CONCEPT LEVEL – The concept of Aliens has a great story behind it. There’s a mystery: A remote base on a faraway planet has gone silent and they suspect that there may be aliens involved. This mystery leads to a goal. Ripley and a team of Marines must go in and figure out what’s happened, possibly having to wipe out the aliens. An intriguing setup for a story.

SEQUENCE LEVEL – Having a strong overall story concept is great, but you need to find a way to keep that concept interesting for 120 pages. If the characters in Aliens just go in and kill the aliens, your story is over within 30 pages. This is where sequences come in – 10-20 page chunks that have their own little stories going on. These sequences are going to have their own goals and their own mysteries. In other words, you must be telling stories within these 15 page segments. For example, the first goal is to get into the base and find out what happened. They get in there, find out everyone’s gone, and discover some traces of a battle. In the next sequence, the aliens attack, and the goal is for Ripley to get to the soldiers and save them. The next sequence introduces a new goal – figure out what to do about this. They decide to go back up to the ship and nuke the place. Except when the ship comes down to get them, it’s sabotaged by the aliens, leaving them there. — The point to remember is: with each sequence, introduce new goals and new mysteries to keep the story entertaining. If you’re not doing that, you’re just writing.

SCENE LEVEL – Storytelling at the scene level is where I can tell whether I’m dealing with a pro or an amateur. Good writers work to make every scene have some sort of mystery or goal driving it. There’s a situation that needs to be resolved by the end of the scene, and the scene isn’t over until that happens. Again, we’re talking about the same tools here. Goals and mysteries. The goal could be as simple as “making sure the area is secure,” which is what the Marines’ initial job is when they go into the base. Or the mystery can be as simple as “what happened here?” which is what drives the following scene – the characters trying to put the pieces of what happened together through the clues they find.

Each of these levels of your screenplay should be telling compelling stories or we’re going to get bored. I run into really interesting story concepts all the time that turn into boring screenplays because the writer doesn’t know how to tell stories on the sequence or scene level. It’s like they figure, “I came up with a cool idea for the movie. I’m finished.” NO! You have to come up with a cool idea for every sequence! Every scene! Think of each of those as MINI-MOVIES, all of which have to be just as compelling as the overall idea. Because I’ll tell you this: if you write three boring scenes in a row in a screenplay, you’re done! The reader’s officially given up on you. Try to tell a story every time you walk into a scene.

There are obviously smaller tools you can use to enhance your storytelling as well. You can throw unexpected twists in there, suspense, dramatic irony, a character’s inner journey. But if you’re a beginner/intermediate, focus on the basics first. Goals and mysteries. Goals and mysteries. Always remember: No matter how good of a writer you are, how strong your prose is or how well you can describe a scene, unless you’ve set up a story where we give a shit about the characters in that place, it won’t matter. Screenwriting is not a writing contest. It’s a storytelling contest. The sooner you realize that, the faster you’ll succeed in this business. I PROMISE YOU THAT.

Genre: Sci-fi/Comedy

Premise: A hapless and broken hearted barista is visited by two bad-ass soldiers from the future who tell him mankind is doomed, and he alone can save them.

About: This script from British writer Howard Overman sold in March of last year and made it onto the middle of the Black List, right next to Desperate Hours! Overman has been a longtime British TV writer, writing such shows as “Merlin,” creating the show “Vexed,” and winning a 2010 BAFTA Television Award for Best Drama Series for “Misfits.”

Writer: Howard Overman

Details: 116 pages – February 2011 draft

Wait a minute.

Hold up here.

Are you telling me that I just read a comedy script…that was funny? And that I liked? Has Scriptshadow slipped into Bizarro World??

Not only that, but a good comedy that was low-brow (the longest running joke in the screenplay is literally a shit joke)?? I always complain about low-brow comedies. Scripts that have nothing to offer other than jokes.

Aha! But Slackfi DID have more to offer. It had a story (with unexpected twists and turns ‘n stuff!) and even some character development. By the way, what does that mean exactly? “Character development?” I see that phrase thrown around a lot and I’m not always convinced that the people who throw it would know how to catch it if it was thrown back.

Character “development” is any instance of your character developing into a different person. This can be through overcoming a flaw, overcoming the past, or in the case of The Slackfi Project, overcoming a relationship.

But I’m getting ahead of myself. Which is fine, I suppose, since there’s time-travel in Slackfi. However, I don’t get the nicest responses when I dislike time-travelling scripts these days. So thank God I enjoyed this one.

20-something Josh sleepwalks his way through his coffee shop job. The guy can whip up a mean vienttia grand-aye half-whip double-sauce cinnamon-style frappe mocha-chino (apologies to all if I’m getting the terms wrong. I’m not a coffee person) but is bored out of his gourd while doing it. Josh is the kind of person where smiles go to die.

But at least he has a reason for it. His girlfriend, Zoe, dumped his stupid ass a few months ago and now toys with him. She wants to hang out, but then she doesn’t. She wants to go on dates, but then she cancels. She wants to have sex, but then the next morning thinks it was a bad idea. God was not a nice dude for creating people like this but they’ll be around for as long as people don’t have the balls to walk away from them, and unfortunately, Josh’s testicles haven’t grown to “walk away” proportion yet.

So how does one deal with devil-chicks like this in the meantime? By playing video games with one’s apartment-mate of course! Josh and his buddy, Apollo, are quite a team, getting high while ridding the alien planet Tressor of the dangerous race: Plekisaurians. But when Apollo says he’s grown up and wants to do more adult things with his life, poor Josh finds himself with only one friend left, his overweight guinea pig, Mr. Tibbs!

Until one night when he’s visited by the duo of Wolf and Tiger, a badass male-female team who claim to be from the future! They tell Josh the world is a week away from a pandemic that will kill 6 billion people. Josh is the only one who can save them because he delivers sandwiches to the lab where they test guinea pigs, who are responsible for the virus. “Deliver sandwiches?” Josh responds. But he’s a barista. Wolf and Tiger look at each other, then double-check the address. Oops, they’re in the wrong apartment. They meant to go to Apollo’s apartment!

“Sorry,” they say, and leave. Bummed beyond all reasonable definitions of the word, Josh happens to run into Wolf, Tiger and Apollo the next day, when they’re attacked by micro-chipped bad guys from the future called Replicants. Apollo is killed, leaving Wolf and Tiger with no choice but to go with Plan B, Josh!

Unfortunately, while gearing up for the big attack on the lab, the police get a hold of Josh and explain to him that Wolf and Tiger are a couple of whack-jobs who escaped from the nuthouse. They made up this whole thing about the future based on their obsession with the Terminator and Matrix franchises, and right now, they’re being escorted back to Crazy City.

At this point, Josh doesn’t know what to believe. Are these two really crazy, in which case he should move on with his life? Or in doing so, is he killing six billion people? It isn’t until Josh confirms that his own guinea pig – MR. TIBBS – is a secret spy for the replicants, that he shifts into high gear! He must find a way to break Wolf and Tiger out of the nuthouse, come up with a plan to get into the lab, and then….well and then massacre hundreds of guinea pigs so they can’t spread the disease. All while his annoying ex-girlfriend keeps trying to ruin his life!

Okay, so let’s get back to that character development thing I was talking about. When you write a script, you want to ask yourself, “How is my main character going to develop? How are they going to change?” If they’re not developing into anything new or different, that means they’re staying stagnant. And for the most part, stagnant is boring.

Overman uses a relationship to develop his hero, Josh, coupled with a flaw. The relationship is obviously his one with Zoe. He allows her to treat him like shit and is afraid to move on. Overman cleverly creates a scenario at the end of the script, then, where Josh is at the lab with Zoe outside the contamination door. He has a choice of either letting her in, which saves her but kills 6 billion people, or leaving her out there to die and moving on with his life.

Remember, this is one of the best ways of conveying development in your character. You give them a choice near the end of the story that basically asks: “Have you overcome your flaw or what?” (Spoiler) In this case, Josh leaves Zoe out there (thank God!) and he’s officially developed into a better person.

BUT, I have a suspicion some of you don’t care. Why? Because I know how a large reading contingent HATES loser wimpy main characters. That’s an issue that’s long escaped me – how to straddle that line. In order to develop your character into a strong person, he must first be a weak person. So how do you make someone weak but still likable? I have to admit Josh was a little too much of a loser for my liking, but the rest of the story was so clever and funny that I still rooted for him.

That’s the other thing I liked here – the story. Most comedies I read have a VERY thin premise that’s stretched to the gills. A joke that should’ve ended on page 7 has been beaten to death for 110 never-ending pages. Slackfi actually had a story that was carefully plotted.

Which reminds me – one of the telltale signs of a good writer is what they do with their midpoint. The midpoint should shift things around a bit, turn what was essentially one story into a slightly different story. I always use the example of Star Wars. It starts out being about some people delivering a message, but then turns into those same people trying to destroy a huge base. In the midpoint of Slackfi, we find out everything Josh has been told is a lie, and that Wolf and Tiger are in the nuthouse. It changes from Josh following along to Josh having to come up with a plan to break out Wolf and Tiger and then save the world.

Anyway, this was a funny little script, and evidence of what I was saying Friday about storytelling being more important than writing. The writing in Slackfi is nothing to write home about. Many of the sentences are stilted and simplistic. Overman also has a bad habit of doubling up on beats, making many moments redundant (i.e. we’ll see Josh get rejected by Zoe and Overman will follow the action by writing something like, “Josh is stung by getting rejected by Zoe” – an unnecessary sentence). But the STORY ITSELF for Slackfi is fun and keeps you reading.

So I recommend this script. It’s a cool little sci-fi project that’s marketable enough to be brought to the big screen. And I couldn’t help but think it would be a perfect double-feature with amateur favorite Keeping Time!

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

What I learned: The midpoint is a great place for passive characters to become active. — Preferably, your hero will be active from the outset (like Indiana Jones). That’s because movies like active characters. But some stories necessitate that the hero start off passive. Starting off passive is fine. What you don’t want is for your hero to be passive for the entire script. At some point, you want them to start driving the story. Through Slackfi and Star Wars, I realized that the midpoint is a great place to do this. Luke doesn’t start taking charge until the midpoint (when he comes up with an idea for how to save Princess Leia) and Josh doesn’t start taking charge until the midpoint (when he has to rescue Wolf and Tiger and come up with a plan to save the world). So consider this option the next time you write a story that begins with a passive hero.

.jpg)