Search Results for: F word

Come back for script on Saturday.

Genre: Fantasy/Adventure

Premise: (from IMDB) The mortal son of the god Zeus embarks on a perilous journey to stop the underworld and its minions from spreading their evil to Earth as well as the heavens.

About: After discussing the original Empire Strikes Back draft before Kasdan came along and turned it into a classic, I decided it would be nice to look at something Kasdan wrote today. And it turns out he wrote a couple of drafts of Clash Of The Titans, the long rumored remake which is finally making its debut in theaters this Friday. The writer who worked on Titans before Kasdan and who is said to have really taken it to the next level, is none other than Travis Beachem, who broke onto the scene with his much beloved “Killing on Carnival Row” (which you’ll be seeing on tomorrow’s Top 25 list).

Writer: John Glenn & Travis Wright – Revisions by Travis Beachem – Current Revisions by Lawrence Kasdan

Details: 120 pages (May 28, 2008 Draft) – This is not meant to be a review of the movie. We are critiquing an early draft of Clash Of Titans, and that is all we’re critiquing, just the script.

There are a lot of shitty ideas as far as remakes going around these days. They’re remaking “My Fair Lady,” for Christ’s sakes. I’ve never actually seen My Fair Lady. But even as someone who’s never seen it, I know it shouldn’t be remade! Clash Of The Titans is not one of those ideas. It’s actually the perfect film to remake. The effects in that 1981 film were so brutal as to be unwatchable. And what better film to remake than one whose hopes and ambitions were so much bigger than what the budget and special effects could afford at the time?

But man, I did not expect to actually be wowed by the trailer. And that’s what happened. My lips parted and went “wow.” No sound was actually emitted. It was a silent “wow.” A “wow” without sound. And as everyone knows, those are always the most powerful wows.

So good it was that I decided it should have been an official summer release instead of a wimpily served up pre-summer appetizer. But eight years ago when the studios staked their 2010 summer movie plots, the biggest thing Sam Worthington had done was a “Beware Of Dingos” PSA, and thus left the studios unaware that they’d be promoting a film with the hottest movie star on the planet. All this is not to say Clash is a slam dunk. There aren’t many things I remember about the original, but one scene that’s stuck with me over the years is the Medusa scene. Not sure how it would play today but that shit terrified me as a kid. The remake must not only top that scene, but tap into the charm and heart the original, even with all its deficiencies, somehow managed to muster. Does Kasdan’s draft of “Clash Of The Titans” succeed?

Rape. That’s how Clash of The Titans starts out. With the god Zeus raping a mortal Queen. There’s a plan to all of this, of course, but this is not the Zeus I know. If he isn’t careful, he’s going to end up in a bad bad place, or worse – Celebrity Rehab.

Flash to 25 years later and we’re hanging out with the Olympians, a.k.a. the gods, who are distraught over this endless war between them and the mortals. Too many people have died and Zeus wants to put an end to it, a truce. So he calls upon his half-son, the village fisherman, Perseus (who, if you’re keeping score, is the result of the aforementioned rape) to marry Princess Andromeda, thus ensuring a bond between the land dwellers and cloud surfers that will solidify peace.

Only problem is, the snotty Princess would rather go bungie jumping without the chords than marry this half-God stick-flinger. Perseus isn’t so high on the Princess either. He’s too busy trying to figure out when he became a half-God responsible for the biggest truce of all time. A few days ago his biggest duty was deciding between worms and bait.

Complications ensue when the Bitch God Of The Ocean, Tiamut, hears the Queen tell her people that her daughter, the Princess, is hotter than Tiamut. In what may be the most jealous overreaction of all time, Tiamut charges through the gates and lets everyone in the kingdom know that unless they sacrifice the princess to the ocean, she will unleash the Kraken on the city in 30 days. Yikes. Talk about self-worth issues. Did they have shrinks in 805?

Naturally nobody wants to sacrifice the Princess, even though it’s been well-documented that she’s worthless, so they entrust Perseus to go off and find an elusive but “300-worthy” army to protect the city against the Kraken. Perseus and his Fellowship head off into the desert, navigating strange lands and strange creatures to find these modern-day marines and get them back to Jobba before the 30 days are up! Perseus isn’t keen on the journey and is way out of his league, but it’s not exactly like he has a choice.

Along the way the crew encounters beasts, elephant-sized scorpions, eye-less witches, and of course, Medusa. And with each new obstacle, the reluctant Perseus is expected to more aggressively find the leader within himself. Will he? What will the team do when the army they came for can’t fight? Will the city, and more shockingly, the king himself, buckle before the Kracken shows, offering his daughter up to save the city? Aggghhhh! You’ll have to wait until Friday to find out.

Clash of The Titans takes its cues from…well from the very times its set in since that’s when the whole “Hero Journey” thing was born. This well-tread approach, which you might recognize from movies like “Star Wars” and “The Matrix” has a “chosen one” character plucked out of obscurity and thrust into a leadership role before he is ready. He must find the strength within himself before the final battle arrives or risk losing everything…for everyone!

What was strange about Clash Of The Titans, and something I bet they addressed in rewrites, was just how uninvolved Perseus was in the story. I mean full-out blocks of script would go by without him so much as saying a word. Everyone else is dictating the journey, occasionally looking back at Perseus and going, “This okay with you?” I understand he’s not ready yet, but for the first three-quarters of this script, the guy could’ve been a painting and exuded more presence. Of course once we get to Medusa and the finale, that changes. But is it too little too late? Not sure.

The script itself was fairly straightforward, but made two interesting choices. The first was the dilemma the writers put the king in. We routinely cut back to the city during the journey, and each day they get closer, the king has to make the impossible choice of whether to save his daughter or save the city. Remember what I always say. Your script is most interesting when your characters have to make tough choices. And when I say “tough choices,” I mean choices where the consequences are extreme. What’s more extreme than the death of a city vs. the death of a daughter? So that was a nice surprise.

The other interesting choice, and one I’m not as on board with, was telling us how Medusa became Medusa. She was a pretty girl who was also raped by a God (man, those Gods are not nice – I tell ya), and it led to her becoming this hideous cursed ugly thing. And when Peseus goes in to kill her, it puts a whole new spin on the battle, since we have some sympathy for how Medusa ended up in this predicament. It was just a strange unexpected touch that added some complexity to a situation I wasn’t thinking would be complex.

So there’s definitely some good stuff in here, enough to distract us from Perseus being a fairly passive protagonist at least. Nobody nailed the story, but the hammer and the wood are within arm’s length. And really their job was to just not fuck this up. Gods and warriors and beasts and krakens inside a vessel that actually makes sense is pretty hard to fuck up. And they didn’t.

What’s great about Clash, is that it feels different from everything else being released right now. And that’s such a big advantage in this superhero-obsessed market. This could be a massive hit, sneaking (if it’s lucky) into a coveted Top 3 spot for the summer. That’s a big prediction but outside of Iron Man 2, what’s coming out this year? “Cheech and Chong’s ‘Hey, Watch This.” ???

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: What do you want your audience to feel at a given moment? This is a question you have to ask yourself if you want to convey the right emotion at the right time. Leading up to the big Medusa fight, the writers had a choice. They could tell you Medusa’s horrific backstory, in which case you’d sympathize with her. Or they could tell you nothing, allowing Medusa to symbolize pure evil, in which case you wouldn’t sympathize with her at all. In the last decade, writers have been pushed to exercise the former choice. Give your villains a backstory. Make them real and complex. And in most cases, that’s good advice. But know that it is not a blanket rule, and sometimes you don’t want your audience feeling sympathy for the bad guy. Sometimes it’s okay for the bad guy to just…be bad. I bring this up because I’m not sure I would’ve wanted my audience feeling bad for Medusa in this scenario. I want her to be terrifying, cruel, evil, and mysterious. Giving up that backstory erases some of those intended reactions. Always consider the emotional ramifications of your choices, as it’s up to you to decide what you want your audience to feel.

NO LINK!

It’s Day 4 of Alternative Draft Week, where we look at alternative drafts from the movies you loved (or hated). In some cases, these drafts are said to be better, in others, worse, or in others still, just plain different. Either way, it’s interesting to see what could’ve been. We started out with Roger’s review of James Cameron’s draft of “First Blood 2“. We followed that with my review of “The Last Action Hero.” Then I reviewed the original Ron Bass draft of Entrapment. And today we have a biggie. A really big biggie. The very first drat of The Empire Strikes Back ever written.

Genre: Sci-Fi Fantasy

Premise: While Han Solo goes in search of his Father-In-Law, Ovan Marekal, who has political ties with Darth Vader, Luke Skywalker heads to the Bog Planet where he meets a frog-like Jedi named Minch, who teaches him the ways of the force.

About: This is not the widely circulated “4th Draft” which has Leigh Brackett and Lawrence Kasden’s name on it. This is Brackett’s original first draft of the movie, titled, “Star Wars Sequel.” Brackett was best known (outside of her contribution on “Empire”) for scripting the films, “The Big Sleep,” and “The Long Goodbye.” She was also a prolific science-fiction writer, writing over 200 stories of various lengths in the genre. As a novelist, she wrote crime stories and westerns as well. It was in 1978 that Lucas gave Brackett the first shot at his sequel to Star Wars, which at that time, he apparently didn’t have a title for yet. This was based off the success of Brackett’s space opera novels, though she had never written a science fiction screenplay at the time. Sadly, Brackett died of cancer soon after she turned in this draft.

Writer: Leigh Brackett

Details: 128 pages (2-17-78)

So you ever wanted to watch a lightsaber duel between Obi-Wan and Yoda? Well, if Leigh Brackett had her way, you would’ve gotten it.

Sort of.

Heh heh.

Read on.

First of all, I love Star Wars. It’s movie-perfection for me. I could go on about how much I love it but I’d just be rehashing what billions of people have already said billions of times. I’m also not going to give my opinion on the prequels as movies, as that too has been discussed to death. I will, however say something about the screenwriting side of the films. I simply don’t believe Lucas wrote enough drafts of each script. I’m sure he did plenty of nipping and tucking, but every one of those films feels like the beginning of an idea as opposed to a finely tuned execution of an idea. While everyone has their opinions on why the films missed that spark, I simply wish he’d just put more time into the writing process. I honestly think Lucas could’ve figured it out if he’d given the scripts more time. But it looks like he was more interested in the filmmaking side of the prequels. And as a result, the movies are what they are.

Okay, let’s get to The Empire Strikes Back, a film many consider to be the best in the series. It’s a fascinating film to study in screenplay form because it’s a bit of a structural black sheep. It starts out firing on all cylinders, and then descends slowly, over the course of two hours, into a dark almost trance-like meditation on humankind’s obsession with evil. It breaks a ton of rules, both universally and, one can argue, in the Star Wars universe, and still comes out a great film. It is also, commercially, the least successful film in the franchise, and that’s obviously because of a lot of those rules that it breaks.

There’s been a lot of speculation as to how the story for The Empire Strikes Back came about and I’m not sure this answers that speculation, but it’s a fascinating look at the early seeds of what would eventually become one of the most beloved movies of all time. It’s also a particularly great script to read for one’s screenwriting education. You have one of the most well-known stories in history, and you get to compare it to a similar version where hundreds of different choices were made. Since screenwriting is all about choices (Do I make my character do this or that?), we can see how easy it is to make the wrong one.

Now regardless of all that, just as a Star Wars geek, this is fun. I mean, there are some real gems in here. And as messy as this first draft is, we get a few shocking moments. In particular, there are a couple of entire cities that were axed from the film. Darth Vader has a damn castle. And Yoda has a different name! What the fuck?? Anyway, let’s get to it, shall we?

We start off, just like in the movie, in the ice base. But the planet they’re on isn’t called “Hoth.” “Hoth” actually ends up being the name of the planet that houses Cloud City, which is no longer called “Cloud City.” It’s called “Orbital City.” But I’ll get to that later.

A really nice touch I liked, and something that Lucas was accused of abandoning as the series went on, was that we meet Luke looking over this huge beautiful ice ridge. He’s transfixed by its beauty. And it’s a moment very reminiscent of his moment staring up at the two suns back on Tantooine. Just like in the finished film, Luke then gets cut down by a Wampa monster, and dragged back to its lair.

The script starts deviating from the film almost immediately after that however. Han’s Jabba The Hut sub-plot has been scratched. Instead, we learn that Han’s step-father is a man named Ovan Marekal, a huge political bigwig who’s carefully aligned himself with Darth Vader to protect the people of the galaxy. The Rebels believe that if Han can get to him, he may be able to convince him to fight against Vader, giving the otherwise helpless Rebel Army a fighting chance.

The Imperial Walker sequence is also not here. Instead, after they recover Luke and hear his story about the Wampa, they determine that these creatures are a huge threat to the base. And indeed, almost right away, they begin infiltrating and killing the Rebels group by group (kinda like Aliens). If you read the fourth draft, which is much closer to the finished film, you can see that this is actually carried over into that script. So that while the Rebels must deal with the approaching Imperial Walkers, they are also getting attacked from within by the Wampa creatures, who have breached their base. It’s a way cooler scenario, but obviously scratched for budgetary reasons.

When we meet Darth Vader, we meet him in a castle on the planet of Ton Muund, a huge city planet, maybe an early version of Coruscant? The presentation of this city is much more sinister however, and was likely also scrapped for budget reasons. Interestingly enough, we meet the Emperor here for the first time, and he’s wearing a golden robe. The Emperor tells him to go find Luke Skywalker, the man who destroyed the Death Star, because he believes he possesses the force. This is a great screenplay lesson right here, as it’s a mistake a lot of screenwriters make. In the finished film, we see Darth Vader out on his ship, actively searching the universe for Skywalker. His storyline has already begun, the pursuit of his goal clearly in place. Whereas here, we meet Vader waiting around, hanging out, essentially doing nothing. In screenwiting, you want to come into each character’s storyline as late as possible. If Vader’s waiting around to begin with, then you have to waste all this time getting information to him, having him gear up, and finally see him go after his goal. In that case, he might not even get started with the pursuit until halfway through the screenplay. In the film, he’s already started, which is one of the reasons that the movie has one of the best opening acts in history. No doubt this slow start comes from Brackett’s background in novels, where you have a lot more time to explore each character’s storyline. In screenplays, that doesn’t work.

So Han, Leia, Threepio, and Chewie head off in search of Marekal, and Luke ends up flying to the “Bog Planet.” Since Ben doesn’t tell him to go here in this version, I’m confused as to how he knew to go. But he goes anyway. Once there, he immediately meets a frog-like creature named “Minch.” Lucas must have known fairly specifically what he wanted here because most of the Minch/Yoda training sessions are the same, but there are a few key differences. When Minch/Yoda is explaining the ways of jedi swordfighting, he calls on Obi-Wan, who appears, and then Obi-Wan and Minch/Yoda have a lightsaber battle. Not sure how a ghost can battle something real, but it was cool because it was Obi-Wan battling Yoda! Or Minch! Then later, when Luke takes on “Pretend Vader” as his final lesson, the swamp disappears, and the two find each other in the vastness of space. Vader, while explaining the dark side to Luke, even lifts his hand, grabs some stars, and lets them pour through his hand. It’s pretty trippy.

And then, before Luke is to leave, Ben’s ghost tells him he wants Luke to meet someone. A second later, a man appears next to Ben. It’s LUKE’S FATHER! Right. Not Vader! But his real father! Or at least, his real father in this version. Luke’s father tells him about his sister, warns him about the dark side, and then lets Luke go on his merry way. At this point I was so confused I didn’t know whether to have a seizure or pass out. But I loved it. It instantly grabbed me if only for the reason that I now had no idea how this original version of The Empire Strikes Back was going to end.

Back with Han, just like in the film, he’s looking for refuge from the Empire, who’s been chasing him, and remembers his old friend, the Baron Lando Kadar. Before I forget, one nice touch I thought Brackett added in this version, was that Chewbacca is jealous that Han and Leia are spending so much time together. He disgustedly growls whenever the two look all doe-eyed at each other, and Threepio even chimes in and makes fun of him for it. I actually think it could’ve worked in the film.

Anyway, before Han finds Cloud City, he first goes to the planet’s actual surface and finds an ancient ruined city run by Avatar like natives called the “Cloud People,” white skin white-haired aliens who ride on flying Manta-Rays. They’re the ones who tell him about “Cloud City,” which is actually called “Orbital City” here. So up Han goes, where he meets his old friend Lando Kadar, and from here on out, the plot is pretty much the same. Kadar (Lando) has made a deal with Vadar to use these guys as bait for Luke. But there are no bounty hunters here so Boba Fett does not make an appearance.

The one difference, however, is that we get our first real glimpse into the specifics behind the clones (from the Clone Wars). And they are nothing like the clones from the prequels. Lando, it turns out, is a clone from the Clone Wars. Instead of procreating, he’s been using his blood to recreate himself over and over again over time. Whether Brackett came up with this idea on her own or Lucas still hadn’t figured out what the Clone Wars were is anyone’s guess.

Luke finally gets to Orbital City, using the Cloud People to help him sneak in, and the big lightsaber duel happens. The difference here is that Luke is a fucking badass, and HE is the one lifting pieces with the force and hurling them at Vader, beating the shit out of him in their duel in every way. But it’s all a ruse, and we realize the essence of this idea was moved into the final lightsaber duel in Jedi. Vader getting mauled is a trick. He’s allowing Luke to draw on his hatred so he’ll come closer to the Dark Side. All in all, the “dark side” plays a much bigger role in this version. It’s really hit on over and over again. And the film is almost exclusively a character study on Luke’s struggle to stave off that darkness.

Nobody’s hand gets cut off here. After Vader details his ruse, Luke escapes him, hops on the Falcon, and everyone flies away to some flower planet. And there you have it!

If you’re a Star Wars fan, this is a fun read, but as I mentioned before, it’s really a great screenwriting lesson as well. After reading this and watching the movie, you can see how dramatically the script was improved by adding a sense of immediacy and by raising the stakes at every corner. Vader isn’t hanging out back at his city. He’s out actively looking for Luke! The Rebel base isn’t being attacked by puny Wampa monsters. It’s being attacked by the Empire! Han isn’t just being followed by the Empire. He’s being followed by the Empire AND bounty hunters!

Kasdan also understands the conflict between Leia and Han much better. Brackett didn’t identify that their back and forth banter could’ve added a lot of fun to the script, so she only barely touches on it. Whereas Kasdan obviously goes to town with the two, creating one of the more fun romantic back and forth’s in history.

I’ve heard that Lucas laid out the key story points for Brackett and she was responsible for everything else. This is why most of these plot points are still in the finished film, because Lucas had those in place from the get-go. But authors have written that none of Brackett’s contributions were included in the finished movie. I would actually argue that a key element of her draft made it to the final film, and that is the tone. It feels like Brackett set the tone here, and she really does take Star Wars to a darker place than the original film, which was quite a risk when you think about it. It feels like Kasdan recognized and kept that tone, using his more extensive screenwriting knowledge to build a great story on top of it. But since “Empire” is celebrated so extensively for that brave darkness, I believe Brackett should get some credit (and maybe that’s why she does have credit on the final film).

A very fun read if you’re a Star Wars fan. A very educational read if you’re a screenwriter. But as a script, Brackett’s draft wasn’t ready for the spotlight. It’s too bad she died. I would’ve liked to see where she went from here.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read (cause, like, it’s Star Wars!)

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Let’s say you have a scene with a bunch of characters. Make sure every single one of those characters has a goal in that scene. The worst thing you can do is have your characters waiting around for something to happen. That’s not what movie characters do! They DO things. They’re ACTIVE. Being active is what makes them interesting! And it doesn’t have to be something humongous. It can be as simple as trying to find the phone number of an old friend. As long as it’s SOMETHING. Comparing these two drafts, in the Brackett Draft, we meet Vader hanging out on his throne, waiting for information. Compare that to the film, where he’s in his Star Destroyer, gung-ho searching the galaxy to find Luke. Which is more interesting? Or let’s look at the rule on a much smaller scale. In Brackett’s draft, when we meet Han, he’s sort of rummaging around the base, running into people and occasionally talking to them. Compare that to the film, where he’s desperately trying to get his ship fixed so he can get the hell out of here! Which one is more interesting? At the beginning of every scene, take every character and ask yourself, “What are they doing right now? What is their goal in this scene?” You do that and you’ll have a bunch of interesting characters engaging in an interesting scene. You don’t, and you’ll have a bunch of characters standing around doing nothing, waiting for their turn to talk. Which one is more interesting?

Another thing that caught my interest – the fact that budgetary reasons may have led to the key creative choice that jumpstarted this story. I’m betting that Lucas wanted to show Vader in his castle on that city. But when he realized he didn’t have the money, he had to put him somewhere else. Where? Well, on a Star Destroyer. But then he was forced to ask, if Vader is on a Star Destroyer, what is he doing? Where is he going? Obviously, he concluded that he’d have to be going after Luke, which informed his choice to have the Empire attack the base on Hoth. Don’t know if that’s the true genesis of the idea but I’m willing to bet on it after reading this draft. It makes perfect sense. And it may be why the Prequels were so boring in places. Lucas could put his characters anywhere, and by doing that, he didn’t have to have them doing anything, much like Vader in this draft.

It’s Day 3 of Alternative Draft Week, where we look at alternative drafts from the movies you loved (or hated). In some cases, these drafts are said to be better, in others, worse, or in others still, just plain different. Either way, it’s interesting to see what could’ve been. We started out with Roger’s review of James Cameron’s draft of “First Blood 2“. We followed that with my review of “The Last Action Hero.” And today we’re taking on Ron Bass’ draft of “Entrapment.” So enjoy.

Genre: Action/Espionage/Heist/Romance

Premise: An undercover insurance agent is sent by her employer to track down and help capture an art thief. But to do so, she must befriend him, gain his trust, and help him with his next heist.

About: Ron Bass wrote the original draft for this 1999 caper, which was widely praised. But over the course of a dozen drafts, Don Macpherson & William Broyles Jr. took it in another direction, creating what some believe was a lame excuse to pair together two hot actors at the time, Catherine Zeta-Jones and Sean Connery. Ron Bass, who we’ve reviewed before, began writing at the age of six while bedridden with a childhood illness. Although he loved it, he decided on a more practical career after his college professor told him he’d never be published. He graduated from Harvard Law and began a successful career in entertainment law, eventually rising to the level of partner, but the writing bug never left. So he returned to it and had his first novel published in 1978 (“The Perfect Thief”). Producer Jonathan Sanger optioned his third novel “The Emerald Illusion”, opening the door for Bass to become a screenwriter.

Writer: Ron Bass

Details: 118 pages (1st Draft, December 2, 1996)

It would be nice if I could lay out all these stories with the same kind of detail I did “The Last Action Hero,” but, contrary to popular belief, I don’t have access to the Hollywood Development Archives. Much of what I have here is cobbled together from lore and heresay. What I can tell you about Entrapment though is this: Ron Bass’ first draft is something I’ve been hearing about forever. Supposedly, he’d whipped together a wickedly sharp romance-caper that had everyone in Hollywood talking. Unfortunately, over the course of 12 drafts, much of the greatness that was in that early draft was left on the typing room floor – or so it is said. The big complaint was that the producers had taken a cool edgy flick and turned it into a mountain of cotton candy, a lame piece of Hollywood fluff. But fluff turned out to be exactly what the masses wanted (doesn’t it always?) The movie opened on May 7th of 1999 to a surprising 20.1 million, dethroning a little film called “The Matrix” from the top spot. It ended up making 220 million dollars worldwide, but was quickly forgotten three weeks later, like a lot of movies at that time, its memory swallowed up by the behemoth of George Lucas’ long-awaited return to Star Wars, “The Phantom Menace.” Either way, no one can argue that the movie didn’t do well. The question is, could it have done more? Would this draft have made Entrapment the kind of film we still talk about today? My memory of the flick is that of a geriatric old warbler and a woman young enough to be his granddaughter, running around and flirting a lot, which, to be honest, made me very uncomfortable. I also remember tons and tons of really cheesy dialogue. So I was interested to see if this initial draft was free of all that.

Gin Baker is a young sexy insurance agent whose job it is to recover stolen paintings for high-class clients. When an expensive painting is stolen out of a 70th floor John Hancock Building condo, the crime scene’s handiwork points to one person, Andrew McDougal, an internationally known super-thief. There’s only one problem. Andrew is 60 years old and has been off the thief-circuit for over a decade. Why would he come out of retirement to steal a relatively unknown painting?

Well that’s what Gin is going to find out. She travels halfway across the world and finds McDougal (or “Mac”) at a major art auction. She uses plenty of skin and her big smile to lure Mac in, but he’s immediately wary of her, knowing this game is full of people pretending to be someone they’re not. But Mac’s not immune to the temptation of flesh either, and allows Gin into his circle, at least for the time being. After an impromptu theft, the two head back to his suite for some seriously age-inappropriate sex.

I’m not going to mince words. This portion of the script is awful. It amounts to two people trading cheesy supposedly sexually-charged barbs in the same 1-2 “setup and payoff” rhythm you’d get from a Sesame Street skit. There’s no spontaneity, no originality to the dialogue. It’s just “setup” “payoff” “setup” “payoff” over and over again. For example, Mac would say to Gin something like “Better get an umbrella. I hear it’s going to rain.” Her reply: “That’s okay. I like being wet.” Or Gin would say, “Escaping those guards will be hard.” Mac’s reply: “I’d rather be hard than soft.” That’s not real dialogue from the script. But it might as well be. This is what you have to trudge through in these first 50 pages.

This is exacerbated by the overuse of commentary in the action, where every single nuance, every single eye flicker, every inner thought is supplied in detail in between the dialogue. Here’s what I mean:

MAC

I stole your suitcase when I left you at the bar. I have since sent it on to the States, with three chips, well hidden.

Are you following.

MAC

Since you aren’t there to claim it, the bag will sit at Customs. Safe. Unless…

No smile. No smile at all.

MAC

They receive. An anonymous. Tip.

Jesus Fucking Christ.

GIN

That’s entrapment.

MAC

No. Entrapment’s what cops do to robbers.

We can feel her heart pounding from here.

That’s what it’s like for the entire script, or at least the first half. The biggest problem with this, especially when combined with the endless flirty dialogue, is that it makes the entire romance come over as if it’s trying too hard. We feel like it’s being forced down our throats: These two like each other! They really fucking like each other!!! And I understand that this is a first draft and that the tone and originality of the dialogue will be worked out over time, but it’s just I heard such good things about this script and I’d assumed that meant addressing my main problem of over-the-top cheesiness.

The structure during this portion of the screenplay is a mess as well. Although we know that Gin is trying to retrieve the original stolen painting, we never met the person who had the painting stolen, and therefore don’t really care whether they get it back or not. Nor is there any specific urgency in obtaining the painting, no timeframe or time limit. For that reason, the only reason for the story to exist is to listen to an over-sexed Nursing Home patient and a playmate with grandfather issues to banter mindlessly amidst an occasional fuck.

It isn’t until Mac (spoilers here) “reveals” to Gin that he’s an art thief and wants to include her on his next job that the story picks up. But even here, as he trains her for the job, the plot device feels like an excuse to give these two more time to exchange sexual innuendos and flirtatious quips. The training sequences, which involve stuff like jumping out of planes, are devoid of any tension, because there are no stakes at all. We aren’t told what Mac’s after and therefore don’t care if he succeeds. It’s all really boring.

But then…

It’s as if Bass all of a sudden realized what his story was about (more spoilers) and the script does a complete 180. There’s a couple of well-executed twists, the primary of which is Gin revealing that she’s not really an insurance agent, but a thief. Her job is cover, as well as a sly way to figure out where and how to get the very paintings she’s supposed to be protecting. And that while Mac thought he’d been testing her to see if she was capable of pulling off his job, all this time she’d actually been testing *him* to see if *he* was capable of pulling off *her* job. And that job is what brought me back on board – the plan to steal 8 billion dollars.

And this is where the draft and the film differ. Whereas the film places the climactic heist in the Petronas Towers of Kuala Lumpur, Bass’ draft focuses on the 1997 Hong Kong change-over back to China. While the execution of this storyline is superior to the film version, I can’t help but notice that it’s a change that needed to happen. You can’t release a technology-heavy movie in 1999 about 1997. It would be like making 2012 in 2013.

Whatever the case, the last 50 pages of this script are really well-constructed. The twists are executed to perfection. The multi-stage heist (which includes invading a mountain guarded by an army) is both inventive and exciting. We see things we’ve never seen before in this type of movie. And whereas the first half of the script has zero tension, the pursuit of 8 billion dollars really gives the second half the kick in the ass it needs, since the stakes for pulling off the biggest heist in the history of the planet are naturally pretty high.

So to me, Bass’ draft is two separate screenplays, the lame first half and the sizzling second half, which I’m sure can be attributed to this being his first crack at the story. What isn’t solved, unfortunately, is the lame back and forth cheesy dialogue between the two main characters. That was always the big issue for me. And my impression was that this draft would come off as a smarter edgier version of what we saw in theaters. That wasn’t the case.

But you can’t deny the fact that this ending rocks, and if I were 20th Century Fox, I’d extract the big Tapei Mountain Sequence and put it into one of their other big franchises, cause it really is well done. The 8 billion dollar heist is also nicely executed. My experience tells me it should be impossible in real life, but Bass sold it well and I bought it.

Anyway, another interesting peek into development, and an excuse to run to the video store, grab Entrapment, and do some serious procrastination on whatever script you’re working on. But you’ll have to beat me there, cause I’m going right now. :)

P.S. If you’re a fan of these kinds of films, don’t forget to check out my old review of Lovers, Liars, and Thieves.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Chemistry between your romantic leads is essential, but chemistry isn’t as simple as nailing the casting. It needs to start on the page. Now there are exceptions to every rule, but one that’s fairly consistent is: keep your leads from kissing and/or having sex until the third act. Why? Because chemistry is built on the unknown, on our curiosity of if they’re going to consummate the relationship. Think about how sexually charged your relationship is with that certain guy or girl. Why is it that way? Cause you haven’t done anything about it yet! Once you “do it,” the unknown disappears. That sexy spark which permeates through every sentence goes bye-bye. Characters in screenplays are no different. Making them sleep together = losing the fun. Gin and Mac sleep together within the first 40 pages here (I don’t remember if they did this in the film or not) and there’s no doubt that something is lost in the process. Now I’m not saying this is a blanket rule. In a movie like “The Notebook,” for example, which is a memoir that takes place over an extended period of time, the plot dictates that we experience that first kiss and that first sexual experience fairly early. But here, in a movie like Entrapment, which is basically built on the chemistry of the leads, that choice is disastrous, cause you eliminate the big thing we’re all wondering if they’re going to do or not. Interest over.

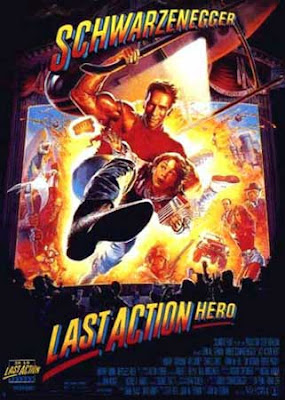

It’s “Alternative Draft Week” here at Scriptshadow, where we look at alternative drafts from the movies you loved (or hated). In some cases, these drafts are said to be better, in others, worse, or in others still, just plain different. Either way, it’s interesting to see what could’ve been. Yesterday, Roger reviewed a James Cameron draft of “First Blood 2.” Today, I’m reviewing one of my favorite spec stories of all time, Penn and Leff’s draft of “The Last Action Hero.”

Genre: Action-Comedy

Premise: A high school kid finds himself inside the world of his favorite action star’s new movie. He uses his extensive knowledge of action films to help the hero, Arno Slater, navigate the story and beat the bad guys.

About: Zak Penn and Adam Leff wrote this as their very first screenplay and sold it soonafter. It was subsequently rewritten by Shane Black, which is the draft that made it to theaters. The story goes that those who originally championed the project felt that a cool edgy flick was turned into a silly watered down PG-13 piece of garbage. There are still hurt feelings about the project to this day. Penn has gone on to write the two X-Men sequels, Elektra, and The Incredible Hulk. Leff wrote another script with Penn, PCU, as well as Bio-Dome.

Writers: Zak Penn and Adam Leff

Details: 124 pages (9/9/91 draft)

The Last Action Hero saga is one of my favorite Hollywood stories, and something I’ve written about before. This shows exactly how a seemingly good idea (relatively speaking) can get stirred and shaken and slammed around in Development to the point where it becomes an utter piece of shit, resulting in the kind of movie that convinces the average movie-goer that anyone can write a Hollywood film. For those who don’t know about the way it all went down, settle in and enjoy yourselves. This is a good one.

It all started back in 1991, when Zak Penn and Adam Leff, two college students, thought they could slap together a screenplay and sell it for a million bucks. The idea was to write a screenplay spoofing the action films of the 80s. They called it, “Extremely Violent” and it was about an Arnold Swarchenegger-type action star whose world was rocked when an extremely movie-savvy 15 year old magically crossed from the real world into his film. They thought it would be great to have a guy saying all the things that the audience was thinking, such as, “You should go save your wife now before they use her as a pawn against you later!” Basically the action equivalent of Scream before Scream was made.

The two had one of those “friend of a friend” contacts in the business, who read the script and liked it enough to recommend it to an up-and-coming agent by the name of Chris Moore (yes, Project Greenlight Chris Moore). For those who argue that Hollywood is all a game of luck and chance, this next portion of the story is your ammo. Being Hollywood’s Golden Boy at the time, Moore had hundreds of scripts he was supposed to read, and probably the lowest script on the totem pole was some garbage by a couple of college kids who obviously only got their script on his desk through a friend trying to help them out. Since Moore rarely had any time to read anyway, it was likely this script would never be read. But it just so happened that on that day, his lunch date canceled, and he had nothing to do for an hour. “Extremely Violent” was sitting on the top of the pile, so he thought “What the hell?” picked it up, and started reading it. He instantly fell in love with it. Thought the tone and the story were perfect. And it immediately become his number 1 priority project.

So Penn and Leff got the call of a lifetime (which they, of course, thought was normal, having no Hollywood experience). A big agent loves your script. They’re going to try and sell it. The script goes out, and low and behold, it SELLS for hundreds of thousands of dollars! Two college kids are living the dream. It’s true! Anybody can write a screenplay! (that’s the sound of me sighing)

But Moore didn’t want to just sell this thing. He wanted to get it made. So began the next step, which was to package the script with the kind of talent that would bring buzz to the project. Of course at that time, there was no bigger name in the writing world than Shane Black, the author of such films as Lethal Weapon and The Last Boy Scout. Now the irony here was that Penn and Leff wrote the script parodying Black’s writing style (in the same way that the movie parodied action films). But all that was white noise. Moore knew if he could get the hot Black onboard in some capacity, the film would have a shot at getting made. So they sent him the script, and low and behold, Shane loved it! He immediately decided he wanted to produce the project.

Now even though Shane was on as producer, the unspoken hope of everyone was that Shane would rewrite it. With Shane being the hottest writer in town, a script written by him was guaranteed to be made. Although Shane resisted at first (he’d never rewritten anyone before) there was a key piece of the puzzle that needed to be addressed. For this project to be a sure-fire go-picture, they needed an A-List star. And the obvious choice to play the main character in the movie was the biggest movie star in the world – Arnold Swarchenegger. The likelihood of Swarchenegger signing on to a script written by two nobodies was slim. But if Shane Black rewrote the script….then maybe – just maybe – they could nab him. And so the rewrite process began.

Everything started off wonderfully. Shane told Penn and Leff that all of their ideas were welcome. He would send them pages, get their take, and a collaborative effort would be made to bring this thing home. After the very first exchange of pages however, Penn was livid. He felt that even in these small doses, Shane had already ruined a lot of the key things that made the script work. After a couple more meetings, things became so heated that fights almost broke out. In retrospect, the reason for this is fairly obvious. You had a writer who had never rewritten anyone before. And you had a writing pair that didn’t understand how the development process worked (just the fact that they were *invited* to participate in the rewrite should’ve been cause for celebration). Since there was obviously no way the project could continue this way, Penn and Leff were told to take a hike.

Here is Penn’s explanation of why the changes Shane made were so terrible…”They added mobsters. They’re taking the movie out of the strict action movie genre and trying to make it a parody of many different kinds of movies. Some of it’s a parody of James Bond movies, some of it’s a parody of action movies, and some of it’s a parody of buddy camp noirish movies. It’s pretty astounding to see how badly they screwed it up,” Penn said, laughing.

Zak felt that Shane shifted the parody of the hero to much more of the Mel Gibson-Bruce Willis archetype. The “wisecracking, angry down-on-his-luck cop, which is a pretty enormous change and pretty much pervades every line of Arnold’s dialogue. I think, frankly, that it hurts the movie tremendously, because the whole point of the movie was the counterpoint between the kid who’s smart and like us, and the other character who’s a fantasy character, who’s an idiot, who’s literally one-dimensional.”

Shane shot back that Penn can say what he wants, but the reality is that his draft is the one that got Arnold on board, and therefore ultimately got the movie made. Now whether the script got Arnold on board because Arnold genuinely liked it, or because Shane was the biggest writer in town and his vision was more trusted, we’ll probably never know (unless anyone’s got a direct line to the Govenator). But this brings up a larger issue, and one of the major failures of the development system – which is letting an actor influence or change key aspects of a story. Most actors don’t understand how to craft a story, just like most writers don’t understand how to craft a performance. Any time you allow an actor to change major story elements, you’re playing with fire, and this is exactly what happened when Swarcheneggar demanded changes.

Arnold was initially disappointed that his character was too “two-dimensional” and wanted his character to be deeper. On the surface this sounds like a smart request. “Three-dimensional character” is a buzzword the industry lives by. But the whole point of Arnold’s character WAS that he was two-dimensional. That’s why he does all these dumb things. That’s why he needs the help of a 15 year old kid. That’s the exact thing the movie is making fun of, the fact that these action characters are so two-dimensional. So by adhering to this request, the writers and producers were knowingly making the movie worse. Of course, what was the alternative? Let the biggest action star in the world walk? Of course not. You gotta do what he says.

The final straw in the original writers’ eyes was to change the kid’s age from 15 to 12. This ended up sanitizing the harder edge they were going for and officially turned the movie into a kiddie film. The thought behind the choice was, younger kid equals broader appeal which equals larger box office, but the opposite actually happened. The audience sniffed out that the producers were trying to please everybody, and stayed away in droves (though I’m not convinced this decision wasn’t influenced by the fact that the John Conner character from Terminator 2 – released just two years prior – was closer in age and tone to the Danny character from Penn and Leff’s draft – maybe they were afraid the characters would come off as too similar?).

But I think the ultimate question here is, was the spec draft really any better than the script that became the film? Or was this a misread from the get-go, a silly idea that never should’ve been turned into a movie in the first place? Interestingly enough, Chris Moore still talks about the project, haunted by the fact that it turned out so bad. He still believes it could be made into a great movie, and looks forward to the day when everyone’s forgotten it, so he can remake the thing and try again.

THE REVIEW

Now I was told the draft I read was the original spec but looking at the title page, it’s titled, “The Last Action Hero.” Since we know the original spec was titled, “Extremely Violent,” this may be one draft removed from that spec. Chances are it was probably an attempt to clean up the script before they sent it out to the big names, like Shane Black. Anyway, something to keep in mind.

“The Last Action Hero” introduces us to 15 year old Danny, a clever but introverted kid who embraces his loner label by escaping into the beautiful city of New York, or, more specifically, an old rundown movie theater where he watches as many movies as they’ll play in a day. His favorite films are those starring super action star “Arno Slater,” whose new movie, “Extremely Violent” is coming out next week.

The reclusive projectionist of the theater (and Danny’s only friend) sets up a private screening for him so he can watch “Extremely Violent” before anyone else. During the screening, a tear in the screen causes a cosmic merging of reality and fantasy and sucks Danny into the very movie he’s watching. Before he knows it, he’s standing right next to his hero, Arno Slater!

The two are immediately attacked by the film-within-a-film’s bad guys, “The Twins,” and not only do the Twins promise to kill Arno, they promise to kill his new friend (Danny) as well! For this reason, Danny and Arno have to stay together so Arno can protect him.

Danny figures this is probably a dream and decides to ride it out. He warns Arno that because of the collateral damage he caused in his previous action scene with The Twins, he’s about to be screamed at by his always-angry captain, but Arno doesn’t know what he’s talking about (he’s a movie character and therefore has no idea what’s coming around the corner, even though it’s obvious to all of us). He’s completely shocked then when they get back to the station and he’s screamed at by his captain! Danny was right! But how did he know that? This is followed by another typically 80s action movie scene where Arno goes home to his purposefully cliché wife who only exists to dress his wounds and tell him everything’s going to be okay.

Danny becomes acutely aware that this world he’s in operates exclusively under movie conventions, and realizes he can prevent a lot of the unnecessary danger and violence that Arno would encounter. He points out that the real issue isn’t the Twins, but the big ultimate conspiracy. If they can figure out the conspiracy now, they don’t even have to deal with The Twins or any other nonsense. In essence, they can cut straight to the end. All this does though is make Arno’s head hurt because he doesn’t think three moves ahead. He thinks like an action-movie hero, in the here and now. And the here and now usually involves shooting a bunch of bad guys and figuring out the consequences later.

This sort of back-and-forth is the central conflict of the story. Danny tries to teach Arno how to think three steps ahead and avoid all unnecessary violence, and Arno resists, preferring to shoot the hell out of anyone who gives him a mean look (again, very similar to Terminator 2, which makes me think that a lot of Black’s changes were out of his hands – he had to make them to differentiate the dynamic between the two films).

The Last Action Hero is actually a good idea for a movie. Part of the fun of watching popcorn films is predicting what’s going to happen next, which, even if you’re a minor movie buff, is fairly easy. To create a character who essentially says what all of us are already thinking is the kind of device that plays well if done right. Especially back in the 80s when every action film was so mindlessly predictable.

But my biggest problem with the script is that it doesn’t take advantage of this opportunity. For example, when Danny and Arno go back to the precinct, Danny observes, “You’re about to get chewed out by your captain.” Where is the drama inherent in a random observation like that? Why aren’t we using Danny’s “powers” to create drama? For instance, it would be much more interesting if, say, he offered: “No no. You can’t go back to the precinct. Your captain’s going to yell at you and take away your badge and then you won’t be able to stay on the case!” Now Arno has to make a decision. Does he listen to the kid or ignore him? Because a choice is involved, the moment is dramatic. Same goes for the following wound-dressing scene. It’s sorta funny to see a paper-thin female lead exist only to dress Arno’s wounds, but if it’s just observational, then all we’re doing is spoofing action flicks a la “Scary Movie.” Danny doesn’t even need to be there for that. And if Danny doesn’t need to be there, what’s the point of having him in the first place?

This eventually changes later in the script when Danny starts calling the shots. He tells Arno they need to go get his wife so the bad guys can’t use her as a pawn later (which is kinda funny because the wife is so used to being used as a pawn that she actually resists being protected before she needs to be). And then, instead of going into a lair full of bad guys where he’ll surely get hurt, Danny advises Arno to go to a public place and call 50 policeman for backup so there’s no way the bad guys can possibly hurt him. Now we’re taking advantage of the concept, but it was a full 75 pages into the story, and in my opinion, too late. By that point, I’d checked out.

I’m also surprised, taking into account the nature of the story, Penn was so pissed about Black’s decision to turn Arno into more of a “Gibson/Willis” archetype. Swarchenegger wasn’t known for being a cop in his films, so the fact that Penn and Leff made him one already went against how we identify Swarchenegger. So Black extending that into the Gibson/Willis arena was at the very least a natural progression of what they’d already started.

Anyway, my guess is that “The Last Action Hero” is one of those scripts that was lucky to be written in the golden age of specs, when a great concept was all you needed for a sale. It likely wouldn’t have a chance in today’s stingy market. Though in fairness you could say that about most specs of yesteryear.

So which draft do you like better? Or should this script even have been purchased in the first place?

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Well first of all, I think you need to exploit your concept to the fullest. Whenever you come up with a great movie idea, you want to sit down and write out all the possible scenarios that will best take advantage of that idea, then include all the “hits” from that list in your script. But because this script is really about deconstructing clichés, it’s a good reminder to always perform a “cliché check” run-through of your script. Read through it with the specific intent of asking yourself at every stage, “Will the audience know what scene is next?” “Will the audience know what line is next?” Because stories have a certain pattern, there is going to be an inherent predictability to your story. But the key moments should be unexpected and original.

For those who want to hear Zak’s reaction to the ordeal, follow this link.

The story behind “The Last Action Hero” comes from the book, “The Big Deal,” by Thom Taylor, which details the development process on a number of spec screenplays. You can find the book on Amazon here.

Michael Stark is here for the sequel of, “Ten Books That Need To Be Turned Into Movies.” His taste gives the list a distinct new flavor. Because there’s so much script-book crossover reading, I’m wondering if I shouldn’t start putting up some book reviews on the site. Any book fans out there that would like to write some reviews for the site? Maybe you could submit something to me. In the meantime, get those lists ready cause tomorrow (Wednesday) at noon, I’m putting up the “Reader Script Faves” post. Get your top 10 scripts lists ready. :) Here’s Michael Stark…

That ever-so-polite-and-gracious Roger Balfour neglected to tell you faithful readers who gave him the idea for his little book report a few weeks back. It generated a ton of discussions (that’s what Script Shadow lives for) and a few other fringe benefits for good old Rog.

After his alter ego got all that brainy, literary, cyber tail, here I am in the internet bookstore I run out of my house, lonely, unappreciated, looking through my dusty tomes for a few suggestions for part deux.

Here are my ten:

1. High Rise by J.G. Ballard

“As he sat on his balcony eating the dog, Dr Robert Laing reflected on the unusual events that had taken place within this huge apartment building during the previous three months.”

“As he sat on his balcony eating the dog, Dr Robert Laing reflected on the unusual events that had taken place within this huge apartment building during the previous three months.”

Think The Lord of the Flies set in The Towering Inferno.

Now, this is by the guy who wrote Crash. Not the Academy Award winning, Paul Haggis, real life in LA, multi-culti/multi-cast/multi-storied Crash, but the Crash about Symphorophiliac sickos who can only get off by getting themselves into sensational, limb-losing car accidents.

Yup, that Crash. Ballard is kinda the English Gentleman version of Chuck Palahniuk.

High Rise is pretty sick too. Probably would need David Cronenberg directing to pull it off. I think the nightmares I got after reading it is what got me off the concrete island of Manhattan and into a nice, little house in rural Georgia.

Written in 1975, the social relevance is timeless. Cram too many people in a fabulous high-rise apartment complex with all the amenities and modern conveniences (gym, shops, pool, high-speed elevators, an Urban Outfitters, etc) that you pretty much never have to leave …

And, then, let the building go to total shit …

And, then, watch what happens to the inhabitants.

It’s like the Tipping point. Once the building starts breaking down, society starts breaking down too. Class systems emerge and begin warring against each other. Floors vs. Floor.

Eventually, none of the condo owners are going to work or even stepping foot outside the building. They remain inside to fight and protect their turf. When food sources start to dwindle, the annoying barking dog across the hall suddenly becomes fair game. And, perhaps, a few weeks later, the gal who snubbed you in the laundromat.

It’s George Romero directing an episode of Big Brother.

Okay, I’m not the only freaky fan who wants to see this on film. Producer, Jeremy Thomson, has owned the rights for nearly thirty years! Someone, please, help the guy out!!!

2. THE TOMB by F. Paul Wilson

“The Tomb is one of the best all-out adventure stories I’ve read in years.” – Stephen King (President of the Repairman Jack fan club)

“The Tomb is one of the best all-out adventure stories I’ve read in years.” – Stephen King (President of the Repairman Jack fan club)

Nuff said. Who can argue with Uncle Stevie?

Repairman Jack isn’t the fix it guy you call when your old Norge is on the fritz or the john is overflowing, but he’ll definitely crawl through some pretty serious shit for a client. It’s like hiring Burn Notice’s Michael Westen and getting all the Ghost Busters along for the ride.

The Tomb was the first of a planned 15-book cycle (not including some short stories and young adult novels) featuring Jack, the Manhattan Mercenary for the Little Guy that can’t help but take cases that are gonna veer mid-way through off into the supernatural.

Jack, not unlike Lee Child’s Jack Reacher, lives pretty much off the grid. He doesn’t have a last name, vote, pay taxes or talk to census-takers. Unlike most action/adventure heroes, he’s pretty much an average guy without super powers or military training. He’s just naturally good at bashing bad guys whenever the Joe Franklin Show isn’t on.

In The Tomb, Repairman Jack is asked to retrieve a stolen necklace. Of course, his client neglects to tell him about the ancient curse it carries and the Bengali demons it’ll ultimately unleash. And, that said demons – the Rakoshi — would be going after the adorable daughter of Jack’s extremely hot ex-girlfriend.

Chicago may have hosted the Night Stalker and Harry Dresden, but NYC and the Boroughs are the perfect stomping grounds for Jack and “The Otherness” monsters he keeps finding himself pitted against.

Jack has been able to get himself out of a lot of tough scrapes, but hasn’t been able to budge from development hell. According to Wilson, six screenwriters have had at this potential franchise over the past 12 years.

Possible solution: Episodic TV ala the Dresden Files? I’m just saying…

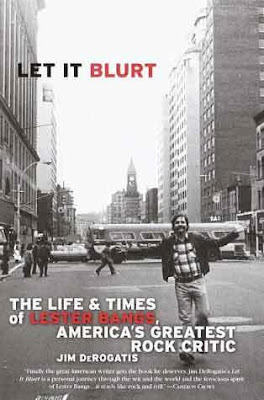

3. Let it Blurt by Jim DeRogatis

“The only true currency in this bankrupt world is what you share with someone else when you’re uncool.” — Lester Bangs

“The only true currency in this bankrupt world is what you share with someone else when you’re uncool.” — Lester Bangs

A lot of people got introduced to the wisdom of Lester Bangs when Philip Seymour Hoffman played the world-weary bear of a rock critic in Cameron Crowe’s Almost Famous.

I grew up reading Lester’s rants in Creem magazine, back in the early 80s, when music really, really, really sucked. And, this wonderful, wonderful man introduced me to an exciting, new type of soundz that was only a 45-minute train ride away from my nice, safe Long Island home. He changed my life. Changed millions of others too.

He wasn’t just a rock critic. He was the Hunter S. Thompson of the music world. I mean, Lord, the guy could write a 30,000 word screed of a record review that talked to your soul. So, why isn’t he in the Hall of Fame? Bangs pretty much championed heavy metal and punk when Rock n Roll seemed to be on its last legs.

I know they’ve been trying to develop Please Kill Me, the Oral History of Punk into a movie for the longest time. I’ll help you guys out. If you suits wanna make a flick about the time period when punk rock broke, ya do it by focusing on the man who coined the fucking term. You shoot it through his eyes and ears.

Bio pics ain’t easy. And, movies about writers seem to be the ultimate taboo in Hollywood. But, the life of Bangs is the exception. He partied faster and louder than any of the rock stars he wrote about. Growing up with a fervent Jehovah’s Witness of a mother, Lester would grow up to evangelize just as hard and passionately about the Devil’s music she despised.

The book starts out with Bangs jamming onstage with the J. Geils band in a packed out arena, the critic, playing what else? — An electric typewriter! TAT TAT TAT along with the noize. Now, if that ain’t a great opening sequence, I don’t know what is.

Ya got his ongoing battle against the corporate suits making shitty albums, his longstanding feud with Lou Reed and a cast of supporting characters that include Alice Cooper, Patti Smith, Iggy Pop, The Ramones and the Clash. Who the hell wouldn’t want to be in this movie, playing their favorite rock icon?!! Who wouldn’t want to play Lou Reed? Who wouldn’t wanna be Bangs?

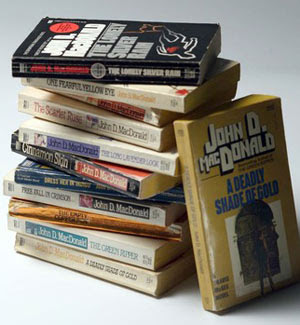

4. The Travis McGee novels by John D. MacDonald.

Again, you gonna argue with Uncle Stevie?

Some of you kids will know John D. Macdonald for penning the book that would become Cape Fear. But, Man, the prolific sonofagun penned 78 freaking books! Most of them extremely worthy of your time.

Travis appeared in 21 of them. Ask any mystery fan. This is the guy they most want turned into a celluloid hero.

And, yeah, they tried before. And, failed. First in 1970 with Rod Taylor. Then, again, in 1983 with Sam Elliot, for a failed TV pilot. The first clue that they fucked it all to hell was when they moved the famed local from Fort Lauderdale to Southern California. Sheesh!

Unlike other detectives, McGee is neither a cop nor a gum shoe. He’s a “salvage consultant” who recovers your lost or stolen property for half their value. He is a tough guy, knight-errant, beach bum, sex therapist and philosopher. Like Carl Hiaasen many years later, MacDonald uses his character to make comment on the corruption and trashing of his home state.

McGee lives on a houseboat, “The Busted Flush”, that he won in a poker game and drives a custom Rolls Royce, Miss Agnes, that has been transformed into a pick-up truck. His best friend is Meyer, a hairy economist who often provides the Holmesian deduction skills to solve their cases. Ha! His boat is called The John Maynard Keynes.

Fiercely independent, McGee would retire after every case. Then take on a new client only after the money had run out -– or if the client was an old friend (the man had honor) or was exceptionally hot (the man was also pretty horny). Each case had enough corrupt businessmen and sadistic killers to keep things interesting.

McGee is also a product of his times. Half paternal figure and half Hugh Hefner. I guess he’s the fictional character most of us bookworms wish we could be. I’d live on a houseboat too if it weren’t for my blasted allergies!

A rumor has it that Leo is damned close to playing him. YEA!!!! Wish fulfillment. Just keep it in Florida, dudes. Or a lot of librarians are gonna be after you.

5. Carter Beats the Devil by Glen David Gold.

Remember how much Script Shadow raved about the unproduced script, Smoke and Mirrors? Well, who the hell doesn’t love period pieces with magicians?

Remember how much Script Shadow raved about the unproduced script, Smoke and Mirrors? Well, who the hell doesn’t love period pieces with magicians?

If Captain Carson would’ve let me, I probably could have populated this entire list with tomes and bios about showmen, tricksters and prestidigitators.

That’s my thing. I love magic. My first paying job as a tween was doing kiddie magic shows.

So, Carter edged out Robertson Davies’ Fifth Business for the conjuring book I most want to see on the big screen. Good job, Mr. Gold. Beating out the Canadian Gabriel Garcia Marquez is a pretty freaking impressive feat.

And, it’s his first freaking novel too.

I’m enamored … and fucking jealous.

Early 20th Century San Francisco. Famed illusionist Charles Carter, has to flee the country after the President, Warren G. Harding, mysteriously dies after volunteering for one of his tricks.

In his act, in front of a sold out crowd, he had chopped the president into little pieces, cut off his head and fed him to a lion, before restoring him to prefect health.

Now, that’s a tough act to follow. Try that David Blaine!

This book has got every trick in the book. Sideshows, handsome FBI agents, beautiful blind chicks, impossible escapes, The Marx brothers, caged beasts, fast motorcycles, the invention of television and plenty of schemes and scoundrels with devastating secrets.

How does it end? Pretty much in the show to beat all shows. Carter must indeed beat the devil to save the ones he loves.

Shit. The whole book is just that magical.

From what I’ve read, Magic-loving Tom Cruise (He had Mandrake, Houdini and Blackstone pics in development too) still has the rights to the book.

Thus, unless Robert Towne starts waving a magic wand soon, escape from development hell looks hopeless.

6. Secret Dead Men by Duane Swierczynski.

A few weeks ago, Roger put Swierczynski’s Severance Package on his list of adaptations he’d most like to see.

Yup, I’d love to see that one get made too, but Secret Dead Men is my fave. It’s the one they’re gonna have to reunite Spike Jonez and Charlie Kaufman to pull off. It’s one of the most surreal, metaphysical novels I’ve ever read.

And, it’s framed as a detective thriller.

Del Farmer ain’t your ordinary hardboiled, private dick. Instead of collecting fingerprints, he collects the souls of the recently departed to help his investigation of the Association, a mob outfit right out of Richard Stark’s Point Blank.

Farmer keeps all these souls in his” brain hotel” and if a particular skill set is required, he’d let the right dead man for the job control his bod to get it done.

Quel perverse! Sartre meets Sam Spade.

See, some years back, journalist Del was murdered by the Association. So, he has some motivation to see this case through. He had been picked up by a soul collector who, when he decided to walk towards the light, handed the keys to the brain hotel over to him.

The idea may be a tad too unique for mainstream audiences. But, the budget doesn’t have to be too big. An Indie perhaps? A Dexter styled series? Who knows, maybe the French will pick it up.

They are a country of philosophy majors.

7. Vixen by Ken Bruen

“Ask any modern crime writer who they’re paying attention to in the world of crime fiction, and they’ll all point their fingers across the Atlantic at Ken Bruen.” – Roger Balfour, Script Shadow Review

“Ask any modern crime writer who they’re paying attention to in the world of crime fiction, and they’ll all point their fingers across the Atlantic at Ken Bruen.” – Roger Balfour, Script Shadow Review

I’m a big time Bruen fan. Hell, I love noir. But, this guy serves it up nice and lean for a change. And, I sure as hell don’t wanna see the knife he used to do it with.

Here’s a Whitman Sampler from Vixen:

A loud bang went off in Doyle’s ear and he instinctively pushed the phone away. When the noise had subsided he asked:

‘Was that it?’

He heard a low chuckle, then:

‘Whoops, the timing was a little off but we’ll be working on that. What you have to work on is getting three hundred grand together to make sure we don’t bomb again. I mean, that’s not a huge amount, is it? So you get started on that and we’ll try not to blow up anything else in the meantime. We’ll give you a bell tomorrow and see how you’re progressing. Oh, and in case you’re wondering, the movie playing at the Paradise was a Tom Cruise piece of shit so we kind of did the public a service. You be good now.’

Sold yet?

Then read the fooking book. This ain’t a fooking library.

Vixen is U.K. Noir with the sexiest, ruthless, female serial killer/ bombmaking/blackmailer that ever plagued England!

Trying to capture her is London’s gritty answer to Ed McBain’s 87th Precinct, the bent (in all the various definitions of the word) coppers led by the amicably amoral Inspector Brant.

Unfortunately, one of his bent coppers, Elizabeth Falls, gets into a bit of a far too unhealthy relationship with the witchy woman they’re pursuing.

Thus, we have two great, demented female roles up for grabs.

Thankfully, Hollywood has already sat up and noticed Bruen. His London Boulevard has started filming with The Departed scribe, William Monahan, directing Colin Farrell and Keira Knightley.

The script for Blitz, currently in pre-production, has been reviewed here on Script Shadow. Worth the search, Mate.

8. Positively 4th Street by David Hajdu

“We should start a whole new genre. Poetry set to music. Poetry you can dance to. Boogie poetry! “ – Richard Farina to Bob Dylan

“We should start a whole new genre. Poetry set to music. Poetry you can dance to. Boogie poetry! “ – Richard Farina to Bob Dylan

Imagine Next Stop, Greenwich Village mixed with Bound For Glory.

Uh, not really, but writing ten book reports in a row is starting to get awfully hard! It’s showing right?!! Damned slave driver, Carson. I told him six books. Six fucking books. But, No…….!!!!

Okay, where was I?

Yup, I’m pitching another music bio. But, this time, it’s a four way street.

For you youngsters who have no clue about the title, 4th street chronicles the 60s folk music scene with Bob Dylan, Joan Baez and Richard and Mimi Farina going from playing tiny coffee houses to inspiring an entire generation of young lefties like me.

You’d think it would be Dylan, but the most fascinating and filmable character in this bio pic is Richard Farina, the bohemian poet who often got lost in own web of roguish tall tales. He married Joan’s sister, Mimi, the haunting beauty when she was just seventeen. He, like Dylan, had of course, courted both sisters.

With my mental moviola, I can shut my eyes and imagine the scene where he has to talk his jealous, teenaged bride out of shooting him with his own pistol.

Or the scene of Baez, barefoot in the rain, debuting at the Newport Folk Festival and becoming an overnight sensation.

Or the ones of Dylan playing his headgames on the fragile Joan would just make great cinema.

Four fucking great roles. There’s more then enough talent, egos and love triangles to work with. To get a small taste how charismatic and magnetic Farina was, please click here.

9. The Catcher Was A Spy by Nicholas Dawidoff

Think The Pride of The Yankees meets The Tailor of Panama.

Think The Pride of The Yankees meets The Tailor of Panama.

Sports and Spies. Now, that’s a doubleheader.

Moe Berg was neither an exceptional ball player nor an exceptional operative, but this story would have made a nice project for the Coen Brothers. Hell, it’s pretty much Burn After Reading with the Yiddishisms of A Serious Man.

Berg was definitely the smartest guy ever on the ball field. He graduated from Princeton and Columbia Law School. He claimed to read ten newspapers a day and was fluent in a dozen languages. Guess he had the time, as he spent most of his major league career for the Dodgers and the Sox on the bench.

But, baseball brought Berg to Japan and after Pearl Harbor, his home movies of that trip landed him some intelligence gigs for the OSS. A nice, Jewish ballplayer working for Wild Bill Donovan, trying to capture Nazis seems pretty irresistible. No?

So, the catcher parachutes into Yugolsavia and would hop around Europe on assignment to kidnap any scientists he could find.

He apparently didn’t catch any.

And, when the Cold War heated up, he sold the same Schtick to the CIA, to bring over Russian scientists.

He apparently came up short there too. Both times, however, he stuck the taxpayers with some rather hefty expenses.

After baseball and the spy game, Berg spent the rest of his life, pretty much freeloading off friends and family. Trading these great stories for meals and a night on the couch.

Berg turned out to be a charming guy who talked a dammed good game, but was pretty much a flake and a fraud.

Or was he?

His big fish boastings (real, imagined or just a wee bit embellished) would be a hoot to watch. Unfortunately, Confessions of a Dangerous Mind might have killed any hope of this bio ever getting to the silver screen.

Cause, how many movies about entertainers with a secret spy life can they make?

10. A Confederacy Of Dunces by John Kennedy Toole

“When a true genius appears in the world, you may know him by this sign, that the dunces are all in confederacy against him.” – Jonathan Swift

“When a true genius appears in the world, you may know him by this sign, that the dunces are all in confederacy against him.” – Jonathan Swift

They’re probably gonna screw it up. They’re probably gonna screw it up. They’re probably gonna screw it up. They’re probably gonna screw it up.

But, what the Hell? Ya might as well try, try try.

No pressure, Suits. You’ll just piss off a loyal legion of fans and the whole city of New Orleans if you do screw it up.

Many have tried and failed. From Harold Ramis to direct John Belushi in the 80s. And Brit wit, Stephen Fry, taking a whack at the screenplay in the 90s. Both John Candy and Chris Farley have also been cast at various times, making the project seem positively cursed.

Last I heard, things were all set to shoot with a Soderbergh script, David Gordon Green directing and Will Ferrell to wear the famous green, flapped hunting cap.

He’s gonna have to pack on a few pounds to properly play the role. Cause, it’s a huge role in sooooo many aspects.

Dunces is not only a cult classic comedy but considered a true cannon of Southern Lit. It also comes with a rather tragic backstory. The manuscript was literally fished out of the garbage by Toole’s mom after the author had committed suicide. It took 11 years to get it published, championed by writer Walker Percy (One must read the moving forward he wrote for the book) and would then go on to posthumously win the Pulitzer Prize.

All without the help of Oprah.

Thus, sans Oprah, the movie can now simply be titled: Dunces – Not, Dunces: Based on The Novel, A Confederacy of Dunces By John Kennedy Toole.

Damned mouthful, Oprah.

Okay, I digressed. Like Catcher in the Rye, this is a lot of folk’s all time favorite read. Something you can return to year after year and still end up smiling and laughing out loud.

It’s set during the swinging sixties in New Orleans, a place that has known a lot about swinging since its foundation. All hell breaks loose when Ignatius Jacques Reilly goes with his mom to the department store to buy a string for his lute.

His hysterical run in with the store’s policeman starts this picaresque adventure as Reilly travels further down New Orleans’ underbelly in search of a job, meeting some of the most colorful characters this side of the Catalogue of Cool.

Percy describes Ignatius as a “slob extraordinary, a mad Oliver Hardy. a fat Don Quixote, a perverse Thomas Aquinas rolled into one.” He is the most stubborn, misanthropic, intestinally challenged, pop-culture loathing anti-hero literature has ever seen.

So, who the hell is good enough to be able to play that? Cast your votes here.

Zach Galifianakis? He is a southerner after all.

Guys, if you do manage to pull off this adaptation, we’re gonna sell a ton of green, flapped, hunting caps this Halloween.