Search Results for: F word

Earlier this week, I pointed out that two out of three of Demonic’s first scenes were “sitting down and talking” scenes. I said that I knew, as soon as I watched those scenes, that the movie was doomed. “Sitting down and talking” scenes are the worst types of scenes you can write. They’re stagnant. They’re visually uninteresting. They lack imagination. And they’re just straight up uninspired.

And yet, as several of you have pointed out, you see them ALL THE TIME in movies. How can I possibly say to NEVER use “sitting down and talking” scenes when there are so many of them? To answer this, we have to understand why the majority of “sitting down and talking” scenes are shot.

They’re shot because they ARE THE CHEAPEST AND EASIEST SCENES TO SHOOT. So what will often happen is that a day is running long, you need to get the scene in, so you scrap your more elaborate idea and settle for a “sitting down and talking” scene. This happens all the time. It’s important to note that nobody wants to do this. They’re forced into it by circumstance. So when you see that, that’s often the reason – time and money.

But here’s the thing – as a spec screenwriter, you never have to worry about that. It’s not your job to save money or time. It’s your job to write the most entertaining script possible. In other words, you have zero excuse to write a “sitting down and talking” scene.

I’m sure many of you are thinking of dozens of “sitting down and talking” scenes that you’ve liked and that it’s unlikely were dictated by a rushed production schedule. The opening scene between Zuckerberg and Erica in The Social Network. The fake orgasm scene in When Harry Met Sally. Vincent and Mia at Jack Rabbit Slims in Pulp Fiction. DeNiro and Pacino in Heat.

If it’s such a bad idea to write a “sitting down and talking” scene, why do these scenes exist? It basically comes down to philosophy. If there’s a designed PURPOSE to sitting your characters down to talk, it’s okay to write a “sitting down and talking” scene. Where it’s not okay, is when you don’t know what to do, so you fall back on sitting your characters down and having them talk to each other.

When it comes to the When Harry Met Sally scene, that scene is building up to a huge moment – when Sally fakes the orgasm. Let me ask you a question. Does that scene work if they’re in the car together? No. It requires them being in a big public space with a lot of people around. In other words, the scene was designed around that restaurant. So sitting down and talking made sense.

With Vincent and Mia, the Jack Rabbit Slim’s sequence is a stand-in for a sex scene. The dancing is them having sex. Quentin uses the dinner portion, then, as foreplay. Them eating at the table is all about the sexual tension building between them so that it can explode out on the dance floor. Again, sitting down and talking is by design. It’s not because Quentin couldn’t think of anywhere to put his characters.

Another time when it’s okay to sit your characters down to talk is when the situation warrants it. For example, if you’re writing a romantic comedy and you’re building up to the first date, it makes sense that your characters might sit down at a restaurant for their date.

But this is where things get tricky because I’d argue that you could come up with something more interesting than a restaurant date. Set the date up for the restaurant, but when they get there, they find out that the restaurant doesn’t have them down for a reservation. So they can’t eat there. What do they do? I don’t know, but you’ve already created a much more interesting date than had you sat them down at a table to talk for an entire scene.

Do you see what I’m getting at? Yes, you can write “sitting down and talking” scenes. But there are always better options out there. And those are the options you should be exploring.

Often, the reason we write “sitting down and talking” scenes is due to a mistake we made before we started the script. A story without a proper engine will leave your script sputtering along, fertilizing the pages with very little to do. When there’s nothing for your characters to do, you’re going to start sitting them down to talk – anything to fill up pages.

Look at Raiders of the Lost Ark. Do you remember any scenes in that movie where two people are sitting across form each other just to chat? There might be two or three. But I’m going to bet that, if there are, there’s tons of tension in those scenes, which still makes them entertaining.

The reason Raiders of the Lost Ark doesn’t have many sitting down and talking scenes is because the story engine is so powerful. There’s some of the best GSU (goal, stakes, urgency) in any movie ever. Goal – Find the ark, Stakes – if you don’t, Hitler uses it to destroy the world, Urgency – you got to find it before Hitler does, and he has his entire army looking for it.

When you have strong GSU, YOUR CHARACTERS ALWAYS HAVE SOMETHING TO DO. They don’t have time to sit down and talk. That’s why sitting down and talking scenes are bad. They’re a symptom of a deeper problem – that your story doesn’t have a powerful enough plot engine.

Now things get trickier when you’re writing character pieces. By their very nature, character pieces don’t have giant story engines. I don’t know if movies like Moonlight or Minari have any story engine at all. Also, since those movies are more character driven, the set pieces are built around character interaction. And if your characters are constantly interacting, it’s only a matter of time before they’re sitting down to do so.

When you find yourself in this place, you have to have a creative mindset. Only sit your characters down to talk as a last resort. For example, let’s say you want to write a scene between two characters at a coffee shop. What if you, instead, had them talk on the way to the coffee shop? Or on the way to somewhere else?

Sure, if you have a wife and a husband discussing a problem, you can sit them down at the breakfast table and have them hash the problem out. Alternatively, you could make it so the husband is late for work, and the argument is happening as he rushes to get his clothes on, get the kids ready, and get out the door. That’s a much more interesting way to approach the scene.

With all that said, there are times when you do want to sit your characters down to talk. The biggest of these is when you’ve built up a ton of tension between characters and don’t want any distractions for when they collide. The most obvious example of this is the DeNiro Pacino diner scene in Heat. I had no problem with that being a “sitting down and talking” scene because the movie had done such a great job building up to that moment.

Again, to be clear, this scene is BY DESIGN. It’s not because the writers didn’t know what to do and, therefore, sat the characters down to talk to each other. It was carefully orchestrated. Their sitting down and talking is crucial to the design of the movie.

A few last points about these scenes. If you’re a dialogue master, you’re allowed to write more of these scenes than the average writer. Tarantino has quite a few “sitting down and talking” scenes in his movies. But he’s also one of the top 5 dialogue writers in the world. And great dialogue neutralizes the boredom that typically occurs during a “sitting down and talking” scenario.

The worst type of “sitting down and talking” scene is the exposition “sitting down and talking” scene. If you do that more than once in your script, I guarantee you the reader will stop reading. That is the epitome of a lack of creativity – when you’re so boring that the only scene idea you can think of is your characters sitting down and talking, and then, on top of that, you bore us to death with a bunch of exposition.

Finally, in television, you’ll have more sitting down and talking scenes. They have less time and less money in television so they have no choice but to shoot more of these scenes. But that doesn’t give you a free pass to make the scene boring. If anything, it should challenge you to make the scene entertaining in spite of these restrictions. Make sure there’s tons of conflict or tension or sexual tension or unresolved problems between the characters invovled. White Lotus does a great job of this. When the characters sit down for, say, dinner, they’re rarely on the same page with each other, which creates lots of unresolved conflict that plays out during their conversations, keeping things entertaining.

Can you write “sitting down and talking” scenes? Of course you can. But only if they’re by design and only if you’ve done everything in your power to come up with a better option but came up empty.

Good luck!

Genre: Slow-Burn Thriller/Period

Premise: Set in the 1930s when a giant dust cloud had settled over Oklahoma, a mentally unstable mother and her two children must survive both the dust and a mysterious person using the cover of the dust to infiltrate her home.

About: This script finished with 7 votes on the 2020 Black List. Karrie Crouse is relatively new on the scene. She wrote on HBO’s Westworld.

Writer: Karrie Crouse

Details: 105 pages

Readability: Slow/Clunky

One of my favorite horror movies is The Others. I absolutely love that movie. There was nothing spookier than that trio in that house, with the sick kids who couldn’t endure sunlight. I loved it. Which is why I chose this script. Cause it sounded like an update to that formula. Was it? Or was it dust in the wind?

Margaret Bellum and her family live in the Oklahoma Panhandle in the year 1933. They live in a farm house in the middle of nowhere and have been dealing with a never-ending dust drought that’s already killed one of their kids, who breathed too much dust.

Currently, Margaret is getting her kids, Rose (16) and Ollie (7) ready for their father’s extended absence. He’s got to go to work. Which means these three will be on their own. Well, unless you count the dust as a person, which it might as well be. It’s all anybody in the town talks about.

Speaking of the town, the rumor is that a creepy man has made his way into the area and is appearing inside peoples’ houses, sometimes stealing, other times killing. The assumption is that the dust has driven him crazy. Margaret isn’t convinced that the rumor is real. Although maybe she’s just telling herself that because the alternative is too terrifying to accept.

After the father leaves, Margaret becomes obsessed with all the little cracks in her house that are letting in dust. So she cuts up all her clothes to stitch up those cracks. And yet, the dust keeps getting in. Her obsession starts to worry her daughters, who are not down with a crazy mommy. But what can they do?

Margaret also starts thinking that someone is sneaking into the house at night and stealing things. Just when it seems like she’s imagining it, she catches the man in question, Wallace, a preacher who says he knows Margaret’s husband. Wallace somehow convinces Margaret that he’s good people. But she later receives a letter from her husband that says, “By the way, watch out for a psycho preacher.”

Margaret and her children are able to get rid of the Wallace problem. But now they’re back to square one – Margaret going crazy and all that darned dust! As we creep towards the climax, we get the sense that Margaret might do something drastic to herself and her children. Will the town step in before it happens? Or might the kids finally realize that, in order to survive, they’ll have to turn against their crazy mommy?

It’s appropriate that today’s script is titled, “Dust” because that’s what you feel like you’re looking through when you read it – layers and layers of dust. We talk so much on this site about character and plot and structure and dialogue. But we rarely talk about the words on the page and how they’re constructed to create an engaging reading experience.

The Oklahoma Panhandle circa 1930 is an interesting setting for a movie. A constant onslaught of dust makes for all sorts of unique challenges. Unfortunately, the script is plagued – at least early on – with a writing style that’s hard to follow. I’ll give you a few examples.

“A DINGY HALO OF DUST radiates out from a clean WHITE CIRCLE where Rose’s head blocked her pillow from dust.”

While I eventually understood the image this sentence describes, it goes about describing it in an inefficient and confusing manner. A “dingy” halo of dust. Isn’t that redundant? Isn’t all dust dingy? Or is dingy being used to add another layer of dirt? It’s confusing. This is followed by the adjective “radiates,” which seems like the worst possible way to describe dust. Which makes me think I’m reading it wrong. Which forces me to go back and read it again. Which is never a good sign for a screenplay.

It seems like we’re trying to say that there’s a spot on the pillow where there’s no dust because that’s where Rose’s head was. So why not just say that?

“There’s a halo of dust around the center of the pillow where Rose’s head was lying.” That’s it. That’s all you need.

Here’s another sentence from the same page:

“MILK pours into the cup, Margaret quickly places a saucer ON TOP of the cup.”

Sentences become unnecessarily complicated when you shift the action from the person to the object. Milk can’t pour itself. It needs someone to pour it. So starting with milk pouring itself results in a reading hiccup. We *will* understand what you mean. But not without some effort.

This is followed by a comma, and then a brand new sentence. Why is there a comma? The sentence has come to an end. You need a period there.

Why not just, “Margaret pours some milk then places a saucer on top of the cup?” Isn’t that a million times clearer?

A page later, Margaret’s daughter talks about meeting her grandparents. Margaret replies, “They want to meet you too. Maybe next summer. If the crops come in.” Which is followed by the description line, “Margaret quickly moves to the door. Clearly a sore spot.”

How unnecessarily confusing can a simple one-two beat be? The ‘sore spot’ is in relation to the grandparents. But if you read that sentence, you’d think it was referring to the door.

I bring this up because it’s a classic example of a writer trying to be too cute. You’re telling a story. Yet you’re doing everything in your power to get in your own way. Just tell us what’s happening.

I understand that screenwriting contains its own shorthand. For example, you might say “GUN APPEARS, pointed at John’s face,” as opposed to, “Ray yanks his gun out of his holster and shoves it in John’s face.” But you have to be careful with this stuff because, as the writer, you have a lot more information than we do. What you think is clear isn’t always clear.

Because of all these clunky faux-pas, “Dust” exists in this hazy netherworld where the reader only grasps about 70% of what they’re reading. You’re constantly having to go back and re-read pages because you realize, by the end of the page, you’ve forgotten everything you’ve read.

Despite this issue, the script does rebound when Wallace enters the picture. Whenever you insert a potential danger into a home, you create a looming dread that builds all sorts of suspense. We’re terrified of who this guy might be and what he’ll do when he finally reveals his true colors.

Also, some of the stuff with Margaret going crazy, particularly her obsession with sealing up every little crack in the house to keep the dust from getting in, was interesting. I was curious whether she was going to get herself back on track or completely crack.

But these cylinders take so long to get turning that we’ve already made up our mind by that point. Even if I wanted to be engaged, it’s hard to turn it on after 50 pages of a ‘waiting around’ narrative that doesn’t have the easiest writing style to follow.

For all the issues I found in yesterday’s script, Emancipation, this script doesn’t come close to that one in terms of storytelling and writing. There’s such a clear directive in yesterday’s story whereas, with Dust, you get the feeling that the writer is trying to figure out their story as they write it.

So this is another no-go for me, guys.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: When it comes to screenwriting sentence construction, the default approach should be starting with the subject. For example, you would say, “Joe runs” as opposed to, “Running along the sidewalk is Joe.” It’s not that the second example is wrong or should never be used. But it’s usually harder for the reader to follow. Not to mention, when it comes to screenwriting, you’re trying to say as much as possible in as few words as possible. When you start your sentence with something other than your subject, you usually have to use more words.

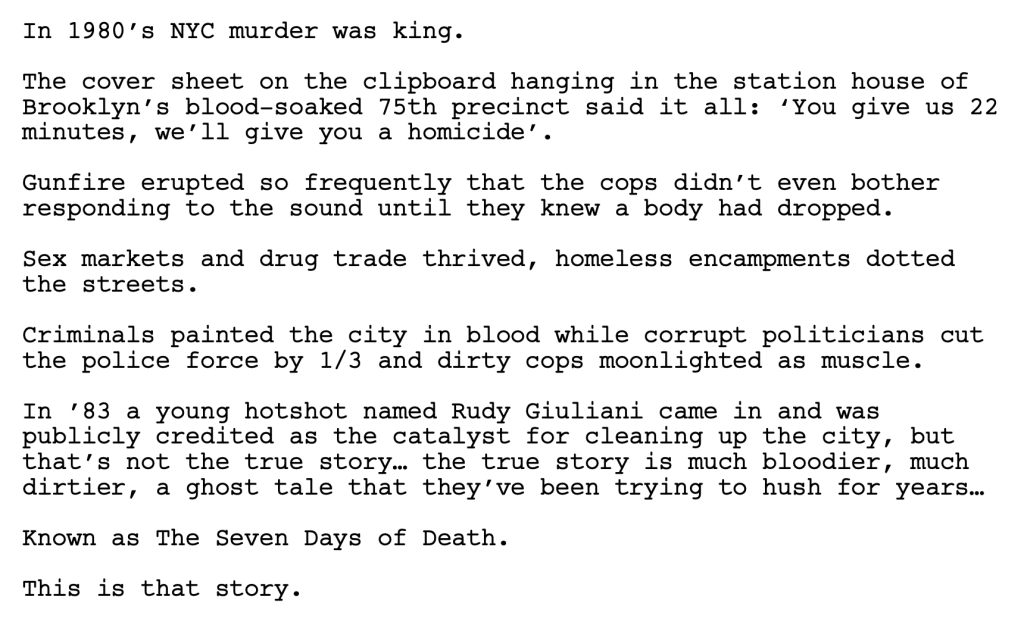

Genre: Action Thriller

Premise: Her father clinging to life in the hospital, a young assassin heads deep into 80s New York City to find the man that put him there, killing everyone along the way.

About: This script finished with 7 votes on last year’s Black List. It comes from a new writer, Jason Markarian, who is repped by the spec sale king, David Boxerbaum. The script is not yet set up anywhere.

Writer: Jason Markarian

Details: 104 pages

Readability: Relatively fast

It’s funny.

I was chatting with a writer the other day and the topic of titles came up. He didn’t like the title of his script and wanted to know if I had any better options.

I’m notoriously bad with titles. Like most people, the only time I know a good title is when I hear it.

And make no mistake, titles matter. A good title can not only create curiosity about a script, it can build anticipation for the story (“Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind”).

The question is, how do you find good titles? The closest I’ve come to an answer is: IT’S RIGHT THERE IN YOUR SCRIPT. Often the title of your script is hiding inside the script itself. It might be a word. It might be a phrase. It’s anything that when you read it, you perk up and think, “Hmm, that’s catchy.”

Look no further than “Bella” as an example. “Bella” isn’t a very good title. I’m not against the “protagonist name as title” option. But it’s pretty safe and, so, isn’t going to get anyone excited to read your script. In fact, it’s probably going to do the opposite. It’s going to make your script sound just like every other script.

So imagine my surprise when I read the opening page and saw that the title WAS RIGHT THERE FOR THE TAKING. Let’s see if you guys can spot it. Here’s the page…

We’ll cover what that infinitely better title is in a second. But first, let’s check out the plot of Bella.

Our movie starts with Bella infiltrating a 1982 New York disco where “Staying Alive” by the BeeGees is blasting onto the dance floor, except Bella is doing everything in her power to have nobody stay alive. She kills almost everyone on the dance floor and we gradually learn that these are mostly (but not all) mobsters.

You see, someone riddled her cop father with bullets (he’s currently clinging to life at the hospital) and she’s going to pull an Inigo Montoya on his ass. The big difference between Bella and Inigo Montoya, though, is that INIGO MONTOYA DOESN’T ALSO DECIDE TO KILL 500 OTHER PEOPLE ON HIS WAY TO KILLING THE SIX-FINGERED MAN.

Yes, this is a bloody script. Very bloody. Pretty much all Bella does is kill people. How much killing are we talking about? Well, at one point, because there is apparently not enough time in the movie to cover all the killing, the screen divides up into 16 different squares so we can make sure to get all of Bella’s kills in.

Bella teams up with her former NAVY SEAL priest who taught her everything, and her former bad boy boyfriend, Jericho, to infiltrate every pocket of New York’s seedy underbelly to find out who shot dad. This eventually puts her on DEETS’s radar. Deets is a cop who’s determined to stop the bloodshed.

After Bella successfully evades him for most of the second act, he locates her and the two prepare for battle. But when Bella gets the chance to kill him, she doesn’t because he’s a cop just like her father. And that would make her a hypocrite. Bella saving his life seems to spark something in Deets, who shifts his priority from taking down Bella to taking down his corrupt police department! So that’s what he does, exposing all of the bad meanie police in this town. The end.

If you answered, “What is ‘Seven Days of Death,’ Alex,” you win! That definitely should’ve been the title.

To say that “Seven Days of Death,” aka, “Bella,” is an overly-stylized script would be like saying TikTok is a minor player in the social media market. Here’s a page from early in the script to give you an idea of what we’re dealing with.

Here’s the thing about overly-stylized scripts. If they’re not written to perfection, they come off as try-hard. By that I mean you can see how hard the writer is trying to be cool and stylized and irreverent.

Now you may ask, “What’s so bad about try-hard? It’s a fun writing style. People should lighten up and enjoy it.” The problem with try-hard is that the reader becomes acutely aware of the writing. Which means they’re NOT focused on the story. And I’d argue the reader should always be focused on the story, not the person writing it.

I’ll admit that this isn’t an across-the-board opinion. Plenty of people enjoy highly-stylized scripts. I’ve enjoyed a few of them over the years. But no matter how good you are at writing them, they cast a long “Please love me and my writing” shadow over the screenplay that’s hard to shake.

With that being said, was the script good?

Let’s start here. One of the things I promote on this site is exploiting your concept. Identify what’s unique about your concept (hopefully you thought about this when you came up with the script idea) and give us scenes that can only take place inside of that concept.

This is 80s New York. What can you show us that’s unique to 80s New York? Well, there’s a scene early on where a guy is getting his rocks off at a Peep Show joint. But as he opens the window curtain, he does not see a naked woman but rather Bella killing bad guy after bad guy. The scene is specific to the time and place of the concept.

That I liked. And Markarian does a lot of that.

But for every moment like this, there was another moment that felt familiar. For example, when Bella needs to up her kill game, she goes to the cemetery, digs up a grave, opens the coffin, and we see it’s filled with guns. Wasn’t this in one of the Terminator movies? And a dozen other movies? And every action script I’ve read in the last half decade? If you’re going to be the cool stylistic ‘look-at-me’ writer, you need to be original. You can’t recycle cool moments from other movies.

Also, like a lot of these overly-stylized scripts, the writer realizes, at a certain point, that clever phrasing and balletic night club shootouts aren’t going to be enough to keep the reader emotionally invested. We’re going to have to tell an actual story here with actual characters. And so the tone of the script shifts as the writer tries to play catch-up with all the emotional beats that weren’t laid out in the first half of the movie.

It’s a bit confusing for the reader, who now feels like they were given the bait and switch. Which the writer ALSO begins to realize, which sends them back into stylistic mode, giving the script a schizophrenic feel.

I wouldn’t call Bella bad. I just think it wants so badly for your to love it that, like anything that covets attention, it eventually becomes a turn-off. In the writer’s defense, this script is written to be a movie. And, with the right director, it could be a “John Wick meets Joker” type situation. It just wasn’t my jam.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: I like movies where the pursuer also becomes the pursued. It can get a little monotonous if your “John Wick” character is doing all the chasing. To spice up the narrative, create a character who chases your John Wick. That’s what Markarian does here. Midway through the screenplay, Deets starts tracking Bella while Bella tracks down her guy.

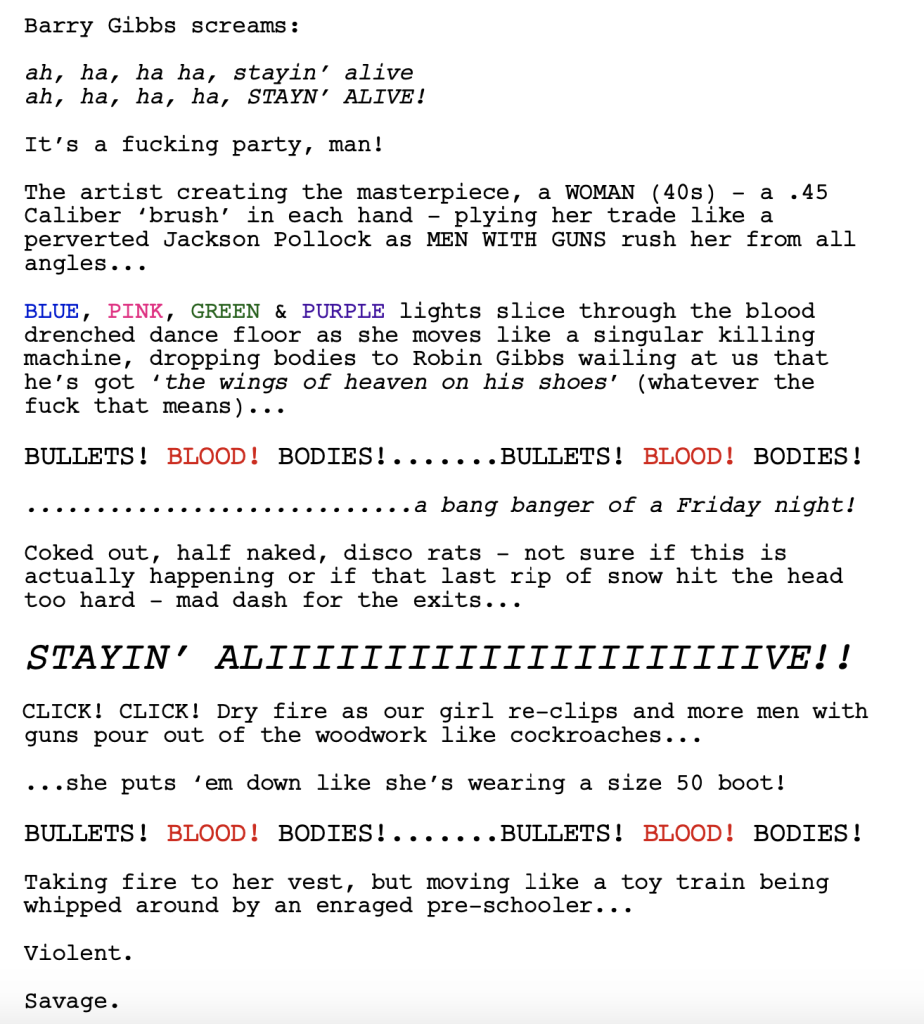

Genre: Horror/Comedy/Action

Premise: In modern day Detroit, Dracula’s eponymous servant, Renfield, is fed up with his abusive boss. So he puts in motion an exit strategy.

About: This is a project that came together two years ago with horror superstar Robert Kirkman (The Walking Dead) coming up with the idea. It’s part of the new Universal mandate to explore their ‘monster’ IP as a set of unique films as opposed to an interconnected universe (a la Avengers). The project is written by Ryan Ridley (Rick & Morty), will be helmed by Chris McKay (Tomorrow War), and will star Nicholas Hoult. It’s important to note that this is the 2019 draft so the script has likely evolved since then.

Writer: Ryan Ridley

Details: 98 pages

Readability: Very Slow

This is a pretty neat idea.

Take one of the most famous characters of all time – Dracula – and introduce a part of him that most people don’t know about – his servant, Renfield. Because the nature of servitude is humorous in a modern context, you make it a comedy.

For those of you trying to come up with a concept that lands with people, it’s always good to use characters who are known to audiences. I don’t see “Renfield” being nearly as compelling if Renfield is serving some vampire named Jake. The fact that we’ve got THE BIGGEST MOST RECOGNIZABLE vampire of all time is what gives the concept pop.

Now let’s see if the script is any good.

We’re in Detroit, Michigan, one of the worst cities in the United States. It’s here where we meet Renfield, a 40-something aging-hipster type, in his weekly support group for co-dependents – people who are stuck in abusive relationships that they don’t have enough self-esteem to leave.

After listening to one of the women in the group talk about how her partner sucks, we follow Renfield to an apartment, see him eat a cockroach, gain superhuman powers, then kill the man who we realize is the significant other of the girl in the group. While this is happening, ANOTHER person comes into the apartment – a hitman who also wanted to kill the significant other, and Renfield kills him too.

Renfield then takes the significant other’s suitcase, which it turns out is filled with drugs, as well as the significant other’s body, and brings it back to the sewers, where his master, Dracula, sucks him dry. Renfield then goes home to his apartment. What he doesn’t know is that because of that suitcase, the city’s biggest drug lord, Ella Lobo, is now after him.

Cut to a cop with a serious anger problem named Rebecca. Rebecca is tasked with figuring out what happened in this apartment. She eventually realizes that this Renfield guy is involved. Which means the cops are after Renfield too. When she catches up to Renfield, he falls in love with her, but she hates him because she thinks he’s a serial killer. Their relationship gets even more complicated when he informs her that he’s been Dracula’s servant for the past 100 years and he gains superpowers when he eats bugs.

After the cops catch and throw Renfield in jail, Rebecca really wants to take down the Lobo family and, therefore, breaks Renfield back out of jail and teams up with him. But, wouldn’t you know it, as this is happening, Ella Lobo makes a deal with Dracula, which means that Renfield and Rebecca aren’t just going to have to take down the Lobos. They’re going to have to take down the master himself!

I’ve only seen a few episodes of Rick and Morty but the fact that this is what today’s screenwriter is known for is telling. From the couple of times I’ve watched the show, I’ve found the jokes to be fast and furious and come from everywhere. That crazy disjointed nature is part of why so many people love the show.

But while that may work in half-hour animation, it does not work in a 100 minute feature. As you’ve heard a million times on this site, features need focus (FNF) and “Renfield” doesn’t have any. It doesn’t seem to know what it wants to be. The engine driving the story changes every ten pages.

You can chalk some of that up to an early draft. But I’ve read a lot of first drafts that eventually became movies and what I’ve learned is that if the foundation isn’t solid in that first draft, the story never gets good no matter how many drafts you do.

I mean we start off with Renfield killing people for his master. So far, so good. Then we learn Renfield eats bugs to generate superpowers. That is not a very good idea. Then we have a bag of drugs dictating the plot. Okay, so we’ve just gone from an original concept to a generic one. Then we switch main characters for a while and Rebecca becomes our lead. At this point, the script is off the rails. Now Renfield is considered a serial killer by the FBI so everybody tries to capture him. I’m happy that the writer really liked Silence of the Lambs but that is the wrong plot development for this script. Oh wait, now it’s a team-up movie! Renfield and Rebecca become a buddy-cop team to take down the bad guys.

Again, you can get away with this type of concept-jumping in half-hour animation because the time is short and the level of emotional investment is low. But with a 100-minute movie, you have to build up investment in the characters, as well as the plot, and that requires patience and focus. If you start jumping around to any plot point that you fancy in that moment, the audience will tune you out. Which is what happens here.

Another person who read the script told me they couldn’t even get out of the first act due to how scattered the plot was.

At least one part of the script works: Renfield’s co-dependency support group. If you remember, I told you the other week that you want to be doing MORE THAN ONE THING in your scenes. That’s what the co-dependency group does. First, it cleverly establishes that Renfield is in a bad relationship (with Dracula) that he is trying to get out of. Second, this is also where he finds his victims for Dracula. He gets the names of these support group members’ evil significant others, seeks them out, and takes them to his master.

When I read that, I said, “Okay, this could be good.”

But literally everything that follows doesn’t work.

Just this idea that he eats a cockroach or a centipede and, all of a sudden, becomes a superhero… I’m sorry but that’s not a good idea. How do you even rationalize that connection? That bugs can provide powers? At least with Ratcatcher 2 (from The Suicide Squad) she had an entire backstory about how she learned to control rats. It was baked into her character. This just felt like one of those exhausted 3am throwaway ides – “What if he like…. GAAINED SUPERPOWERS WHEN HE ATE BUGS???”

Another problem with the script is one I hadn’t considered, which is that you have this looming shadow over the whole story that is Dracula. He is the reason we’re here. As I stated earlier, the movie doesn’t work if Renfield is a servant to Random Vampire Jeff. It works because he’s a servant to the biggest vampire of all time.

And therein lies the problem. We want Dracula. But the more Dracula you show, the more you overshadow Renfield. So what do you do? Neither Kirkman nor Ridley seems to have the answer. Oddly, Renfield doesn’t even live with Dracula. Dracula lives in the sewer system while Renfield lives off in some apartment somewhere. So they’re not even around each other for 90% of the screenplay. That seems like a miscalculation in a movie about a master and servant.

I’m not the comedy expert but I’m thinking your comedy is going to come from your actual concept – which is that Renfield is the servant to Dracula. The comedy isn’t going to come from some 30 year old drugs-in-a-suitcase plotline.

Some of the choices here are kind of baffling to be honest.

You may have noticed that I’ve added a new category to my reviews – READABILITY. Why did I do this? I realized that one of the most important qualities for a script is HOW EASY IT READS. I’ve read 150 page scripts that were breezy reads and 90 page scripts that felt like my eyes were sinking in quicksand. As spec screenwriters, your script’s ‘readability’ should be a top priority.

Readability refers to having a clear and concise writing style. For example, some writers love to be clever. But cleverness only complicates the read, especially if you’re not very good at it. So be clear and concise. You also want to say as much as possible in as few word as possible. Most of the things you say in six lines you can say in three. And finally, some writers have a natural ability to blend words together in a way that’s pleasing to read. All those things make for an easier reading experience.

“Renfield” was clunky. It was unclear. There were giant paragraphs for days. And this is a comedy script. Comedy is the one genre where the readability has to be light-speed. If it’s even medium, its’ not going to work. So “Renfield” was really disappointing on that end.

I wish I had more good things to say about Renfield but unless they’ve come up with a completely different take on the subject matter since this draft, I’m going to say that this project has an uphill battle. The one argument you can make is that it’s comedy and, as we all know, comedy is subjective. I know tons of people who LOVE Rick and Morty so it may be that I just don’t get the comedy here. Which wouldn’t be the first time (I had a lot of these same criticisms for the “Ted” script, for example, and that movie went on to be a mega-hit). So we’ll see. I just wish there was a clearer vision on the page.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: “MARK, 50s, a gentle giant a la John Carrol Lynch, the leader of this support group.” Don’t use obscure real person references in your screenplays. Nobody knows bit actors’ names. Even if they did, when you make references like this, it looks amateur. This is a Screenwriting 101 mistake.

Genre: Crime/Thriller

Premise: A single mother who’s about to be kicked out of her recently deceased father’s home becomes a hostage during a bank robbery that ends in shocking fashion.

About: HBO Max is not playing around anymore. They want their own IP. Which is why they bought up Black Choke. I’m thrilled about this development. The more buyers there are in this town, the more opportunity there is for screenwriters like you to sell scripts. And not just any scripts – ORIGINAL MATERIAL. Which, as we know, is sorely lacking in Hollywood. Black Choke sold last week and comes from Doug Simon, who’s previously appeared on the Black List with his contained thriller, “Breathe,” about a family who’s quarantined in a special underground tank after the world’s air becomes unbreathable.

Writer: Doug Simon

Details: 119 pages

Today’s script is an update on the 1998 movie, A Simple Plan. And dare I say, its execution is even better. Let’s take a look!

30-something Nina Trainer is barley making ends meet. She works two jobs, one of those as a maid. All so she can barely put food on the table for her young son. Nina needs a big break soon since the bank is about to re-claim her home.

40-something Sara, a security officer at that very bank, has seen better days. She was once the best cop on the force, until she tried to save some people from a burning car and has never been the same since.

One rainy day, two men in masks break into the bank and steal half a million dollars from the vault. While this is happening, a dumb teller tries to intervene, resulting in the robbers killing both him and the bank manager. Sara was shot as well and is barely hanging on.

As the robbers exit, they’re forced to take a random person in a rain parka so they don’t get shot by the police. They then speed away. Once inside the van, we pull away the parka hood to reveal… Nina! She was coming to the bank for one last ditch effort to stop them from taking her home.

Later, when they’re driving up the hills, trying to figure out what to do with Nina, she pounces, and the truck goes plunging down the hill killing everyone inside except for… Nina! As Nina is about to call the police, she notices that there’s a car with two dead people and HALF A MILLION DOLLARS inside. Free money! Money that will solve all her problems.

She takes the money, finds and steals a car, and drives home. Nobody saw Nina inside her parka so she’s Scott free. That is until her awful ex-husband, Ray shows up. Ray spots the money and wants in. Because she knows he’ll call the cops otherwise, she’s forced to bring him into the fold.

Meanwhile, Sheriff Keene heads over to the hospital to find that his old partner, Sara, is hanging in there. He wants to know what she saw during the robbery so they can find out who these dudes were. Not to mention the person in the parka they kidnapped. But Keene doesn’t know the half of it. You see, Sara was in on the robbery. And she quickly figures out that whoever her accomplices kidnapped now has the money. She just needs to find that person… and get the money back.

Not long ago, a writer sent me a bank robbery script for a consultation, and my big note to him was that the script didn’t have a hook. It was just characters committing a crime. He came back with a good point. He said, “Did The Town have a hook? Did Hell or High Water have a hook? How bout Heat?” I had to concede that he was right.

However, while a story hook isn’t necessary to sell a screenplay or get a film made, they’re the screenwriting equivalent of having your own publicist. Every time you send your query out, there’s this cool hook dangling there, making it impossible not to request the screenplay.

By not having a hook, you basically cut down the number of people who request your script ten-fold. Let’s run the numbers. If you send a query out for a screenplay that has a great hook, you might get 8 out of 10 requests for the script. If you send a query out for a script that doesn’t have anything resembling a hook, you’ll be lucky to get one request.

In other words, you’re playing 8 lottery tickets instead of 1.

Does that mean you should only write scripts that have a big hook? The short answer is yes. Especially if you’re an unknown. But there’s a bigger point to be made here, which is that, the less of a hook you have, the better the script needs to be. Since less people are going to read it, those people will have to be louder in their endorsement of the script. And they’re not going to be loud unless you blow them away. Let me now ask each and every one of you here at Scriptshadow, how many times are you BLOWN AWAY by a script?

Conservatively…. Once a year? Once every two years maybe?

But this gets into an even DEEPER question, which is, should you assume that you’re the exception? Should you assume that you’re the one writer a year who writes the script that BLOWS PEOPLE AWAY? And therefore, because you are that exception, you don’t need a hook? Theoretically, we should all feel this way, right? If we don’t believe in our writing, who will?

But my whole thing is, why make things harder for yourself? They’re already hard. The odds are already stacked against you. Why not do something that makes things easier for you? You can still believe in your writing. You’re just making sure that more people get a chance to read it!

I bring all of this up because today’s script has a fairly basic premise (it’s got a *bit* of a hook but nothing I haven’t seen before) and despite its pedestrian setup, it’s one of the rare instances where the writing is so good, it makes up for the lack of a hook.

For starters, Doug Simon does an incredible job making you fall in love with Nina Trainer. I’ve talked about using bully scenes to make your hero sympathetic before. If you show a bully picking on your hero early on in the screenplay, we’re going to have sympathy for them.

But you don’t have to approach the bully setup literally. In Black Choke, when we meet Nina, she’s a maid riding up the elevator to clean an office floor. When the elevator doors open, we see a group of drunk laughing office workers who’ve just finished up the day with a party. They stumble into Nina – to them a faceless maid – who then comes out onto a trashed office floor, cake and ice cream scattered about, no thought whatsoever for who has to clean up their mess. This is going to take all night. These jerks have effectively bullied Nina, just in a non-traditional way.

Now, normally, you’d look at this and say, “Who cares? Everyone knows you have to make your hero likable or sympathetic. That’s screenwriting 101. This should hardly be considered ‘good writing,’ Carson.”

But here’s where the skill is. Later in the movie, Nina is going to be doing some bad things. She’s going to be stealing half a million dollars, for example. She’s going to be killing someone. When your hero is going to be doing some truly despicable things, your average “save the cat” or “kick the dog” trick isn’t going to be enough. You have to come up with something that’s going to make us love this character no matter what they do. Which is why this opening is so good. We see this woman being dehumanized by these jerks to such a degree that we’re going to love her no matter what.

Simon also does a kick-ass job of keeping us guessing in a plot where we already know he’s trying to trick us. Pretty much every major story beat had a surprise development in it. Hill achieved this by setting up each plot beat so that you’d only ever assume one outcome. That way, when the other outcome occurred, you were shocked.

When Nina’s ex-husband, Ray, finds out about the money, he becomes the most important variable in the story. Nina can’t do anything without figuring out how to keep Ray happy, since he knows the secret and has to be involved. Now, as a screenwriter, I would tell you that this is dramatic gold. Keep Ray front and center because he complicates Nina’s journey so much. Therefore, when Ray’s accidentally killed later (in a really fun scene), it’s a total shock because the twist HELPS rather than HURTS Nina.

But then Simon hits us with another twist. It turns out Ray told his current girlfriend, Eliza, about the money. She calls Nina, wanting her cut. Which means Simon was able to both give us a shocking twist AND keep the exact same amount of pressure on Nina, by supplanting Ray with Eliza.

There’s a lot more good here I could write about. This script is really clever and really fun. My only complaint is that there are too many characters. I’m not convinced the script needed so many people. But, boy, it’s so well-done. If you want to write a crime script without a hook, check this one out. It shows you where the bar is.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[x] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: I used to dislike small town crime movies. They didn’t have that sheen a big city crime movie has, like “Heat” with Los Angeles. But now I know why they work. They work because the small town setting means everybody knows each other. And when everyone knows each other, you can have a lot more fun with the characters. For example, bank security guard Sara is trying to help Sheriff Keene find the money. Normally, this is a standard pairing. But their scenes are charged because they used to be partners, and when they were partners, they were sleeping together. That’s harder to do in a big city crime movie where the individuals are more separated. So if you’re trying to decide between the two, know that the big city crime movie will feel bigger. But the small-town crime movie has more character possibilities.