Search Results for: star wars week

Welcome to Amateur Week! All week we’re reviewing scripts from amateur writers that got the best response from this post. We’ve already had one script perform REALLY WELL in “Fascination 127.” Will “Chase The Night” be the next big amateur script to celebrate? Let’s find out!

Genre: Drama

Premise: (from writer) On his 25th birthday, a troubled orphan receives information about his estranged mother, sending him into a world of corruption as he investigates the circumstances behind her life and death.

About: I knew this one depended on how unique and compelling the choices were behind the main character’s investigation. That’s what sorta worried me about this logline – that a specific compelling circumstance wasn’t mentioned, but rather a general blanket set of circumstances which were implied. The logline felt a little cold in that respect. But I liked the emotional component of the story, so I was interested to see if it connected on that level.

Writer: Thomas A. Schwenn

Details: 115 pages

Status: AVAILABLE

Star Wars Tuesday. Blood List Wednesday. Disciple Program finishing #1. Halloween yesterday. How is “Chase The Night” supposed to follow all this? Good question. And I’ll tell you my biggest concern reading the logline. I thought it sounded a little boring. That’s not to say it *would* be boring. Just that the logline made it sound that way. Remember, your logline is like the billboard or trailer for a movie. It’s the only thing you have to promote your screenplay. So like a great billboard or trailer makes us want to see the movie, a logline has to make us want to read the script! It has to sound exciting!

Just to remind everyone, faulty loglines can be broken down into two categories. The first is that you haven’t adequately conveyed the excitement of your script. There is no excuse for this. If your script is exciting, you better workshop the HELL out of your logline to make sure it’s perfect and conveys the coolness of your script. The second issue is much more concerning. The concept itself stinks. This goes well beyond workshopping a logline. It means scrapping the entire script. Because no matter how you dress up your logline, how many times you reword it, it’s still going to convey an idea that isn’t very good in the first place. Which is why I always say, get your logline figured out first. Because eventually you’re going to be using that to market your script, and if it doens’t work now, it’s not going to work then.

Actually, I’ve seen this lead to a long-standing trend of trying to dress loglines up into something the script isn’t in order to get reads. You realize, “Ooh, if I stress the ghost aspect more in the logline, even though it’s barely in the script, it’ll sound better!” This is how I would classify Monday’s script, “Pocket Dial,” which promised a lot of modern technology relationship humor in its logline, but didn’t give us any of that in the actual screenplay. Not only is that going to piss readers off, but my question to these writers is, “If that makes your logline better, why didn’t you write that script in the first place?”

Okay, enough bitching and moaning. It’s supposed to be a happy day, a day in which we gorge on all the candy we accumulated last night. Oh, not that I went trick-or-treating last night. No, not at all. Why would someone my age go trick-or-treating? That’s ridiculous for you to even suggest that. I’m just saying that if I *was* a kid and I *did* trick-or-treat yesterday, that I would have a lot of candy that I’m eating right now – or that *that kid* would be eating right now. Not me. Cause I didn’t go trick-or-treating……Man, is it hot in here?

25 year old Tommy Young is not a happy compadre. He carries an old picture around with him showing a young woman, who we’ll come to know as Mariah, hanging out with two friends, Jack and Sam. Although we’re not sure why yet, Tommy has some business with these guys and that business needs to be addressed pronto.

He eventually finds one of the men, Jack (now in his 50s), washed up, drunk, and demands to know about Mariah. It’s here where we get a little more info on the woman. It appears that many years ago, Mariah was charged with killing her parents – Tommy’s grandparents. Yes, Tommy is Mariah’s son. He wants to know the truth about what happened that day, cause he’s convinced his mom would never do such a thing.

Well he’s not going to get that information from Jack because Jack’s Daniel (that’s my clever way of saying he’s wasted). So off Tommy goes to find the other dude, Sam, who’s since become a cop. Jack ends up kidnapping Sam no problem, then ties him up and starts asking questions. Sam denies knowing anything about Mariah, but starts to crack a little as Tommy puts the heat on.

In the meantime, Sam’s precinct gets word that he’s missing and starts looking for him, forcing Tommy to take Sam on the run. It’s here where we’re introduced to the main detective on Sam’s case, Frank Marshall. While Tommy and Sam skitter all over the city avoiding capture, Frank interviews friends of Tommy to get a beat on where he may be holding Sam.

At some point, Sam decides to help Tommy figure out what happened to his mom, although this was a seriously confusing part of the script. Sam is constantly asking to be let go, while also providing details and clues for Tommy to find out if his mom really killed his grandparents. Is he trying to get away or is he trying to help? To be honest, I was never sure.

And that’s pretty much how the rest of the script goes. It’s Tommy and Sam finding clues to help their case while Frank Marshall finds clues to save Sam. I wish I could provide more plot points but there really weren’t any. This was pretty straightforward. Which was the first problem of many I had with “Chase The Night.”

This was a strange script. Because from a distance, it had a lot of components that make up a good story. You have a guy looking into his mother’s murder case. So there’s a goal and a mystery there. And you have the chase aspect going on as well, in that at any moment, Frank could catch them. You also had high stakes, in that Tommy’s trying to free his mother from jail. But despite all this, the script struggles mightily to keep the reader’s attention.

We’ll start with the logline, which states that an orphan receives information from his estranged mother. I never saw that anywhere in the script. So I didn’t even know Tommy was an orphan. And because of that, I coudln’t figure out why he all of a sudden needed to do this. Why didn’t he do it earlier? And to be honest, I couldn’t even tell you what Tommy was trying to do! He just had this picture with these people in it. It wasn’t until halfway through the story that I understood what Tommy’s goal was. I still don’t know if that was done by design or by accident. But plot murkiness is a script killer, and this plot was murky.

But what really bothered me was how detached the writing was. Everything was so…clinical, so cold. The main character wasn’t very interesting. The story wasn’t very interesting. And a big part of that had to do with how little “voice” there was to the writing. All the words were where they needed to be. And it actually read quite well. But it was just so…I don’t know how to put it…”distant.” And that left me bored.

Also, I’m not sure the information in this story is dispensed in a way as to garner the most drama. For example, I didn’t know why Tommy was looking for Jack at first (other than that he was in the picture) so I didn’t care. I guess you can argue that you’re playing up the mystery behind the picture, but if you misjudge how interested the audience is going to be in regards to that mystery, you end up with a really bored reader.

Finally, I could never figure out what the rules of this Tommy/Sam pairing were. Did Sam want to get away? Did he want to help? It seemed like sometimes he wanted to bail (“Just let me leave. They’ll never find you.”) and other times he was Watson to Tommy’s Sherlock. There was this vague implication that Tommy’d convinced him to “do the right thing” and help him find out what happened to his mom, but even that was never clearly laid out. So it just felt comical that these two were running around town together. Are they friends? Are they enemies? I didn’t know!

If I were to give Thomas advice for his next script, I would say to add more character and color to his writing. Let’s have it pop off the page more. Try to be more clear with your plot and motivations as well. We need to know, definitively, why Sam is hanging around Tommy this whole script. We need to know, definitively, what this picture is about, how it got in Tommy’s possession, and why it’s motivated him to become Liam Neeson in Taken. And try to have a few more unexpected things happen during the story. This story unraveled way too predictably. I wish Thomas good luck on his next screenplay. Sorry I couldn’t get into this one.

What I learned: Your 3rd Act twist has to have a properly weighted setup, or else you end up with a “WTF” moment. (Spoiler) So the big twist here is that Stan Bell, the chief of police, covered up his son’s murdering of Tommy’s grandparents, blaming it on Mariah. Except here’s the thing, I hadn’t seen Stan Bell since page 15, where he was introduced for .5 seconds, then disappeared until the final sequence. How is that a satisfying twist? Shouldn’t we know the person who the twist is centered around so that we care? Shouldn’t he have 4-5 scenes of him dispersed evenly throughout the script so his reveal isn’t a total “wtf” moment? Make sure to properly weight your setups people, particularly if they’re setups to a big final payoff.

It’s Unconventional Week here at Scriptshadow, and here’s a reminder of what that’s about.

Every script, like a figure skating routine, has a degree of difficulty to it. The closer you stay to basic dramatic structure, the lower the degree of difficulty is. So the most basic dramatic story, the easiest degree of difficulty, is the standard: Character wants something badly and he tries to get it. “Taken” is the ideal example. Liam Neeson wants to save his daughter. Or if you want to go classic, Indiana Jones wants to find the Ark of The Covenant. Rocky wants to fight Apollo Creed. Simple, but still powerful.

Each element you add or variable you change increases the degree of difficulty and requires the requisite amount of skill to pull off. If a character does not have a clear cut goal, such as Dustin Hoffman’s character in The Graduate, that increases the degree of difficulty. If there are three protagonists instead of one, such as in L.A. Confidential, that increases the degree of difficulty. If you’re telling a story in reverse such as Memento or jumping backwards and forwards in time such as in Slumdog Millionaire, these things increase the degree of difficulty.

The movies/scripts I’m reviewing this week all have high degrees of difficulty. I’m going to break down how these stories deviate from the basic formula yet still manage to work. Monday, Roger reviewed Kick-Ass. Tuesday, I reviewed Star Wars. Wednesday was The Shawshank Redemption. Yesterday was Forrest Gump. And today is American Beauty.

Genre: Drama – Coming-of-Age

Premise: Lester Burnham experiences a mid-life crisis after he’s fired from his job, which ends up triggering chaos in his suburban neighborhood.

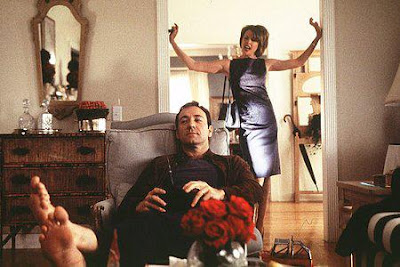

About: Was widely considered one of the best spec screenplays of the last 20 years. But the movie was always going to be a hard sell due to its non-high concept nature. American Beauty went on to become a surprise hit, winning a Best Picture Oscar, as well as 4 other Oscars, including one for Kevin Spacey.

Writer: Alan Ball

Degree of difficulty – 4.5 out of 5

Some of you have suggested that I ditch this mainstream trash and take on movies that are REALLY unconventional. For example, explain why a film like Mulholland Drive works. Well, it’s pretty simple. I *don’t* think Mulholland Drive works. So I’d do a pretty lousy job convincing others of it. I’ve always struggled with Lynch’s appeal. The randomness of his stories always confuses me. So I ask you Lynch-ians, what is the appeal of Lynch’s films? I ask that in all sincerity. I want to know.

Today I’ll be hitching a ride on Kevin Spacey’s train – whatever that means – and reviewing one of the great movies of the last decade – American Beauty. Recently, I watched this movie with a friend who’d never seen it before. I was like, “How could you not have seen American Beauty? It’s awesome.” And she was like, “I don’t know. I just haven’t.” So I forced her to sit down and watch it, and halfway through she turned to me with this frustrated expression and said, “This is just like Desperate Housewives.”

At first I was angry that she wasn’t appreciating the genius of this movie. But I was also trying to figure out if she knew American Beauty came out a decade before Desperate Housewives, and how this would affect our friendship if she didn’t. But after stepping back and thinking about her comment, I realized just how much American Beauty influenced movies and television. It really inspired a lot of copycats, and for that reason, it can never play as original as it did back in 1999. But it’s still awesome, and it still had no business being as good as it was. You want to talk about degree of difficulty, let’s talk about American Beauty.

American Beauty does something I tell new writers never to do: Follow a bunch of characters instead of following just one. It’s okay to follow other characters when they’re around your character, but to jump back and forth between numerous characters and their individual storylines is basically the same as having multiple protagonists. So instead of having to create only one character compelling enough to carry a movie, you have to create six. In addition to that, multiple characters screw up your act breaks and overall structure. You’re essentially having to create multiple three-act stories within a three-act story, and I’m not even going to get in to how hard that is. So yeah, you’re kinda screwed right off the bat.

Also, like a lot of movies this week, American Beauty doesn’t have a very compelling story. In fact, if I described it to you beforehand, you’d probably get bored within 20 seconds. “Well see it’s about this guy. And he like, gets fired. And then he decides to live his life to the fullest. But see, we also watch his family too. And his daughter wants new breasts. And his wife totally hates him. Oh, and the next door neighbors are this military dad and his pot-smoking son…” It just sounds like a slightly exaggerated version of what goes on in everybody’s neighborhood. Why would anyone want to watch that for two hours?

Finally, Lester is an unsympathetic character. He basically says “fuck off” to anyone who doesn’t want to live by his new rules. On top of that, he tries to fuck his high school daughter’s best friend! Let me repeat that. Our 45 year old protagonist is trying to have sex with a 17 year old High School girl. Conrad Hall, the cinematographer on the film, was so concerned about this that he almost didn’t take the job.

Too many characters: check. Weak story: Check. Despicable protagonist: Check. Why the hell did this work?

Ball was smart. He knew that if he followed a bunch of different characters for an extended period of time without a point, we’d get bored. He needed a connective thread – something to bring all these storylines together. He created it in Lester’s death. Ball tells us in the beginning of the movie that in one year, Lester Burnham will be dead. You don’t think much of it at the time, but later you realize that that one sentence turns the movie into a Whodunnit. It’s by no means the dominant focus of the movie, but it gives the movie purpose. I read a lot of these screenplays where writers don’t use that device and they’re almost always bad. In fact, Mark Forster has one of these movies in development called “Disconnect,” (about how we’re all disconnected because of technology). He doesn’t use this device and as a result, the script wanders all over the place.

Next, Ball adds humor. American Beauty deals with some serious ass subject matter. Stalking, death, murder, physical abuse. But the movie is fucking FUNNY. And we’re only able to feel the pain because we’re allowed to laugh. The 7th line of the movie is “Look at me, jerking off in the shower.” Contrast this with another Mendes movie, Revolutionary Road, which had a lot of similarities to American Beauty, but didn’t have a single joke in it. Despite having two of the biggest stars in the world to sell the movie, it bombed. Coincidence? Not thinking so. American Beauty understands that if you ratchet up the melodrama 100% of the time, the audience will turn on you. Make’em laugh and they’ll go as deep as you dare to take them.

Scandalous. A little scandal goes a long way. Old guy with an underage girl? That’s controversial. Controversy intrigues people. It gets people talking. But what Ball managed to do with this storyline was make you understand why our hero did it. This wasn’t about nailing an underage girl. This was about Lester trying to reconnect with his youth. By getting the young girl, it was the physical manifestation of that goal. Also, Ball did a really smart thing by having Mena Suarvi engage in the pursuit. If she would have been some innocent doe-eyed teenager, Lester would’ve looked like a predator. Because she eggs him on, the relationship doesn’t seem nearly as dirty as it could’ve been.

Finally, what I loved most about American Beauty is that I never knew what was coming next. As a writer, it’s your job to surprise the unsurprisable. The audience has seen everything. The readers have read everything. So safe boring choices aren’t going to cut it. Yet, safe boring choices is what I see 99% of the time. American Beauty has its 40 year old protag befriending his 17 year old pot-selling neighbor who’s dating his daughter. It has his wife fucking her real estate rival. It has 5 minute scenes with bags blowing in the wind. It has military closet homosexuals who collect Nazi dinnerware. I can’t remember a movie that consistently surprised me as much as this one. I just never knew where it was going to go. It shows what can happen when you test yourself as a writer and never go with the obvious choice. That’s something we all need to do more of.

Let me finish with this. I’m of the belief that what you have in the script is what you get in the movie. I don’t believe you can do that much to make a script better than it is. Sure you can do a few flashy things here and there, but in the end, it’s about the emotion, and that comes way before a frame of film is ever shot . However, I will concede this belief in one area: the score. A great score can elevate a movie beyond the script. And American Beauty did that. I don’t think without that score that the movie is as good as it is.

Anyway, great movie. Why do you think it worked?

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[x] genius

What I learned: The power of a framing device. If your screenplay has little to no plot, look to build a framing device around it. For example, Cameron easily could’ve made Titanic about two people falling in love on a boat, but he knew there wasn’t enough story to that. So he framed that love story inside a present-day search for a jewel. Now the entire movie had purpose, as there was a point to telling this love story. The same thing happens here. We aren’t just jumping in and out of people’s lives randomly. We’re trying to figure out who’s going to kill Lester.

The movies/scripts I’m reviewing this week all have high degrees of difficulty. I’m going to break down how these stories deviate from the basic formula yet still manage to work. Monday, Roger reviewed Kick-Ass. Tuesday, I reviewed Star Wars. Wednesday, I reviewed The Shawshank Redemption.Today, like is like a box of chocolates.Genre: Comedy/Coming-of-Age?

Logline: A simple man looks back at his extraordinary life.

About: Forrest Gump is the 23rd most successful film in domestic box office history, grossing 624 million dollars if you adjust for inflation. It stole the Oscar for Best Picture away from The Shawshank Redemption and Pulp Fiction (for those keeping track, the other two movies in the race were Four Weddings and A Funeral and……….Quiz Show???). Gump also won Tom Hanks a best actor Oscar.

Writer: Eric Roth (based on the novel by Winston Groom)

Degree of Difficulty – 5 (out of 5)

Yes! I love talking about Forrest Gump. It’s one of those divisive movies that always gets the opinions flowing. People either love it or hate it. I think it’s a great movie, but I understand where the non-likers are coming from. Let’s face it. It’s a smarmy feel good star vehicle that wants you to love it a little too much. But here’s the difference between Forrest Gump and all the other also-rans jockeying for that blatant heartstring tug-a-thon (like “The Blind Side” for instance). Forrest Gump is DIFFERENT. It’s unlike any movie you’ve ever seen and unlike any movie you’re ever going to see. This isn’t some by-the-numbers bullshit. It’s genuinely original. For that reason alone, it’s worthy of discussion.

Let’s start off with the span of time the movie takes place in. Movies are really good at dealing with contained time periods. Why? Because contained time periods provide immediacy to the story. Characters are forced to face their issues and achieve their goals right away and that makes the story move. This is why a lot of films take place within a few days or a few weeks. Once you start spanning months and years and decades, you lose that inherent momentum, and you’re forced to figure out ways to replace it (which isn’t easy!). Forrest Gump takes place over something like 40 years. Not looking good.

But that isn’t the biggest problem for Gump by a long shot. What truly makes the success of this movie baffling is that its main character is the single most passive mainstream protagonist in the history of film. Forrest Gump doesn’t initiate ANY-thing in this movie. He literally stumbles around from amazing situation to amazing situation like a member of the Jersey Shore cast. All of Forrest Gump’s decisions are orchestrated by someone else. People tell Forrest to jump and he says “how high?”. A main character who doesn’t drive the story? You’ve written yourself into Trouble Town. Next train leads to Screwedville in five minutes.

Another issue is, just like The Shawshank Redemption, Forrest Gump has as much plot as an episode of Dora The Explorer (note: I’ve never actually seen Dora The Explorer but I’m guessing there’s not a lot of plot in it). There’s no overarching goal for the protagonist. There’s no drive. No first act, second act, or third act (although I’ve seen people try to break this into acts – it’s never been convincing). Instead, the film plays out like a series of vignettes – or better yet, a sitcom episode. Tom Hanks is thrown into a crazy situation. Something funny happens. Repeat. It’s a very compartmentalized approach to the story. Why these disconnected misadventures worked was a mystery to me for a long time. But I think I finally figured it out.

Why it works:

It came to me like a flash of light. I hadn’t seen Forrest Gump in forever but there the answer to my question was. Forrest Gump wasn’t a movie. It was a documentary. Documentaries don’t have first act breaks and mid-points and character arcs. They simply follow a person’s life and whatever happens to that person happens. All the documentary has to do is capture it. Now as all documentarians know, documentaries are made or broken by their subject. Without a compelling subject, you don’t have a documentary. And that’s why this film worked. Forrest Gump is one of the most fascinating characters we’ve ever seen. He’s “retarded,” yet doesn’t wallow in it. He does extraordinary things, yet is humble about it. His childlike enthusiasm appeals to the kid in all of us. His situation is ironic (he’s extremely successful yet has the intelligence of a 6th grader). This man has a ton going on underneath the hood.

But the characteristic that most ensures the character’s success is that Forrest Gump is the ultimate UNDERDOG. I cannot make this clear enough. EVERYBODY LOVES AN UNDERDOG. When someone is picked on, looked down upon, is a longshot, we love to root for them. And Forrest Gump is the biggest underdog of them all. He’s physically handicapped (as a child). He’s mentally handicapped (as a child and an adult). Yet he achieves things the rest of us could only dream of. It’s entertaining as hell to watch, and it’s impossible not to feel good for the guy when it happens.

Another key component here is the detail given to the supporting characters, particularly Lieutenant Dan. Remember, some protagonists don’t arc. The story just isn’t conducive to them transforming. That happens here in Gump. But if that’s the case, you should probably have one of your supporting characters fill that role, because the audience wants to see somebody learn something by the end of the film (or become a better person in some capacity). Roth recognized that, which is why he has the eternally cynical character of Lieutenant Dan learn the gift of life over the course of the story.

Speaking of supporting characters, Roth also needed some kind of thread to hold the story together. The plot was so wacky, so disconnected, that had he not added a connective thread, it would’ve come off as a series of comedy skits. He needed a constant. And that’s where Jenny came in.

What’s so cool about the Jenny relationship is that everything goes so well for Forrest…except his relationship with her. I said up above that there’s no goal for Forrest and that’s technically correct (Forrest doesn’t actively pursue anything). But he does keep bumping into Jenny. And he does want her. So because there’s an element of pursuit going on, we become engaged. We want to know, will he get her or not?

Remember, movies are essentially characters trying to overcome obstacles. That’s it. And the greater the obstacle, the more involved we get, the more rewarding it is when our character overcomes said obstacle. What’s a greater obstacle than being in love with someone who will never love you back? It’s the ultimate underdog scenario. And our desire to see if he Forrest can pull off the impossible is what gives this movie purpose. Quite simply, we want to see if Forrest gets the girl. And that’s enough to keep us satisfied for 150 minutes.

I’d be interested to hear why you guys believed this movie worked (or didn’t). When I’m in a bad mood, I hate how cute it can be. But otherwise, I get a kick out of how weird and different it is. It fascinates me every time I watch it.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[x] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: If a character has a weakness, don’t allow him to wallow in it. Nobody likes the “woe is me” guy/girl in real life, so why the hell would we like them onscreen? Forrest has a serious disability but he doesn’t let it affect him. He pushes on with a positive attitude. It’s hard not to like someone like that.

It’s Unconventional Week here at Scriptshadow, and here’s a reminder of what that’s about.

Every script, like a figure skating routine, has a degree of difficulty to it. The closer you stay to basic dramatic structure, the lower the degree of difficulty is. So the most basic dramatic story, the easiest degree of difficulty, is the standard: Character wants something badly and he tries to get it. “Taken” is the ideal example. Liam Neeson wants to save his daughter. Or if you want to go classic, Indiana Jones wants to find the Ark of The Covenant. Rocky wants to fight Apollo Creed. Simple, but still powerful.

Each element you add or variable you change increases the degree of difficulty and requires the requisite amount of skill to pull off. If a character does not have a clear cut goal, such as Dustin Hoffman’s character in The Graduate, that increases the degree of difficulty. If there are three protagonists instead of one, such as in L.A. Confidential, that increases the degree of difficulty. If you’re telling a story in reverse such as Memento or jumping backwards and forwards in time such as in Slumdog Millionaire, these things increase the degree of difficulty.

The movies/scripts I’m reviewing this week all have high degrees of difficulty. I’m going to break down how these stories deviate from the basic formula yet still manage to work. Monday, Roger reviewed Kick-Ass. Yesterday, I reviewed Star Wars. Today, I’m reviewing The Shawshank Redemption.

Genre: Drama

Premise: Two imprisoned men bond over a number of years, finding solace and eventual redemption through acts of common decency.

About: Often at the top of IMDB’s user voting list for best movie ever, The Shawshank Redemption was released in 1994 and subsequently bombed at the box office. It later became an immense hit on home video.

Writer: Frank Darabont (based on a Stephen King story)

Degree of Difficulty: 5 (out of 5)

Why the degree of difficulty is so high:

The producers of The Shawshank Redemption along with Frank Darabont expressed shock at how badly their movie fared in theatrical release. Sometimes I wonder if anybody in this business understands how the public thinks. If you give us a boring title, throw two actors on a poster who we don’t know very well, set them in a gloomy shade of gray, have them look depressed and confused, then avoid giving us any clue of what the movie’s about…chances are no one’s going to see your movie.

And even if you did find out what Shawhank Redemption was about, did that help any? A couple of guys wallow in a prison for 25 years. Wonderful. Opening Day here I come.

Besides the depressing subject matter, the movie embraces a 142 minute running time. While that’s not in the same boat as Titanic, it’s a questionable decision due to just how relaxed the movie plays. In fact, this wouldn’t be a big deal except that The Shawshank Redemption is missing the most important story element of all: PLOT. That’s right. A nearly 2 and a half hour movie has no plot! There’s no goal for the main character. Nobody’s trying to achieve anything. There’s no inherent point to the journey. Contrast that with another long movie like Braveheart, where William Wallace is on a constant quest for his country’s freedom. He’s beheading Dukes. He’s taking over countries. That’s why we’re able to hang around for 3 hours. We want to see if he’ll achieve THAT GOAL. What is it the characters are trying to get in The Shawshank Redemption? Pretty much nothing.

So when a movie doesn’t have a clear external journey, the focus tends to shift to the inner journey. This usually takes place in the form of a character’s fatal flaw. A fatal flaw is the central defining characteristic that holds a person back in life. Gene Hackman’s coach character in Hoosiers is bullheaded. He does things his way and his way only. Through his pursuit of a state basketball title, he learns the value of relinquishing control to others, which helps him become a better person.

Neither Andy nor Red have a fatal flaw. They’re not forced to overcome any internal problems. I guess you could say Andy keeps to himself too much and eventually learns to open up to others, but it’s by no means a pressing issue. Red speaks his mind at the end and it gets him parole. But refusing to speak his mind never hindered him in other parts of the movie. In other words, there’s no deep character exploration going on with the two main characters. That’s pretty nuts when you think about it. You have an overlong movie with no plot and no significant character development. That would be like Rocky already believing in himself and not having to fight at the end of the movie. He’d just walk around Philadelphia all day hanging out. So the question is, how the hell did Shawshank overcome this?

One of the main reasons The Shawshank Redemption works is because its characters are so damn likable. Let’s face it. We love these guys! There’s a segment of writers out there who break out in hives if you even suggest that their characters be likable. But Shawshank proves just how powerful the likability factor is. Andy and Red and Brooks and Tommy and Heywood. We’d kick our best friends out of our lives just to spend five minutes with these guys. And when you have likable characters, you have characters the audience wants to root for.

On the other end of the spectrum, Shawshank’s bad guys are really bad. I’ve said this in numerous reviews and I’ll continue to say it. If you create a villain that the audience hates, they’ll invest themselves in your story just to see him go down. Since Shawshank has no plot, Darabont realized he would have to utilize this tool to its fullest. That’s why there’s not one, not two, but three key villains. The first is Bogs, the rapist. The second is the abusive Captain Hadley. And the third, of course, is the warden. Darabont makes all of these men so distinctly evil, that we will not rest until we see them go down. If there’s ever a testament to the power of a villain, The Shawshank Redemption is it.

So this answers some questions, but we’re still dealing with a plot-less movie here. And whenever you’re writing something without a plot, you need to find other ways to drive the audience’s interest. One of the most powerful ways to do this is with a mystery (sound familiar?). If there isn’t a question that the audience wants answered, then what is it they’re looking forward to? The mystery in Shawshank is “Did Andy kill his wife or not?” Now it doesn’t seem like a strong mystery initially. For the first half of the script, it’s only casually explored. But as the script goes on, there are hints that Andy may be innocent, and we find ourselves hoping above everything that it’s true. The power in this mystery comes from the stakes attached to it. If Andy is innocent, he goes free. And since we want nothing more than for Andy to go free, we become obsessed with this mystery.

And finally, the number one reason Shawshank works is because it has a great ending. The ending is the last thing the audience leaves with. That’s why some argue that it’s the most important part of the entire movie. And it’s ironic. Because Shawshank’s biggest weakness, the fact that it doesn’t have an actual plot, the fact that virtually nothing happens for two hours, is actually its biggest strength. The film tricks us into believing that the prison IS the movie so escape never enters our minds. For that reason when it comes, it’s surprising and emotional and exciting and cathartic! There aren’t too many movies out there that make you feel as good at the end as The Shawshank Redemption. The power of the ending indeed!

When you think about it, Shawshank actually proves why you shouldn’t ignore the rules. Doing so made the movie virtually unmarketable. It’s why you, me, and everyone else never saw it in the theater. Let’s face it, it looked boring. Luckily, all of the chances Shawshank took ended up working and the film was one of those rare gems which caught on once it hit video. I’m not sure a movie like Shawshank will ever be made again. That’s sad, but it makes the film all the more special.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[x] genius

What I learned: Shawshank taught me that you can lie to your audience. If you can trick them into thinking one way, you can use it to great effect later on. When Andy asks Red for a rock hammer, the first thing on our minds is, “He’s going to use it to escape.” But Red quickly dispels that notion when he sees the rock hammer himself and tells us, in voice over, “Andy was right. I finally got the joke. It would take a man about six hundred years to tunnel under the wall with one of these.” And just like that, we never consider the notion of Andy escaping again. So when the big escape finally comes, we’re shocked. And it’s all because that damn writer lied to us!

For the month of May, Scriptshadow will be foregoing its traditional reviewing to instead review scripts from you, the readers of the site. To find out more about how the month lines up, go back and read the original post here. The first week, we allowed any writers to send in their script for review. Last week, we raised the bar and reviewed repped writers only. This week, we’re doing something different. I read a lot of amateur scripts. Some through my notes service, some through contests, and some through referrals. I wanted to spend a week (or maybe two) highlighting some of the best scripts I’ve come across. All these scripts are available. So if you’re a buyer and it sounds like something you may be interested in, then get a hold of these writers through the contact information on their script before someone else does. Monday, Roger reviewed a cool script from Michael Stark titled, “Treading On Angles.” Tuesday, I reviewed our first female writer of Amateur Month, Lindsey, and her script, “Blue.” Yesterday I reviewed the sci-fi’ish thriller/procedural, “Nine Gold Souls.” And today I’m reviewing…the next Blade Runner?

Genre: Sci-fi

Premise: In the year 2054, a widowed cop’s job is to hunt down fugitive “translations,” organically created replacements of lost loved ones. After a mysterious murder, he finds himself on the run with a translation of his wife.

About: Aaron is managed by Mad Hatter Entertainment, but does not have agency representation yet. I read this script over a year ago as part of a small contest I held over on the Done Deal message boards. Aaron lives far away from the Los Angeles borders, in St. Louis, Missouri.

Writer: Aaron Coffman

Details: 113 pages

The Translation is another script I read over a year ago and I’ll be honest, when I started reading it, I wasn’t sure if it was going to be any good. As is the trouble with most sci-fi scripts, the writer is tasked with educating the audience about the rules (the “science”) of their world in a very short period of time. And there’s so much to learn here, I initially had trouble keeping up. But once the main story kicked in, I found myself drawn into this modern day Blade Runner tale and loving every minute of it.

It’s 2054. William Monroe is a cop, but a cop with a very specific job – to take down “twigs.” Twigs is the street name for “translations,” copies of people grown to replace lost loved ones – kinda like being able to clone your dog.

Unfortunately, during the time it takes to grow a translation (2 years), many families go through the grieving process and, to put it simply, change their mind. The problem is, society doesn’t know what to do with these discarded clones. And since they can’t be killed, they’re dumped into a sectioned-off ghetto, left to live with only a half the rights real citizens have.

Monroe has a hate-hate relationship with these human copies. He thinks they’re worthless, a mistake society’s made and is too afraid to clean up. So when they escape the ghetto, he’s the one who finds them and does whatever it takes to eliminate the problem.

Monroe takes his job seriously because it’s the only thing he has. His wife, Alyssa, was killed two years ago in a terrorist attack.

Against his wishes, Alyssa’s high-profile parents went ahead and had Alyssa translated, a process only days now from finishing. But when they’re abruptly and mysteriously murdered, the only person left to pick up Alyssa, or this copy of Alyssa, is Monroe. And he’s not happy about it.

It’s supposed to be simple. Monroe picks her up, takes her to the Translation Ghetto, and drops her off. But as soon as he gets her, the fully grown up but childlike curiosity of Alyssa begins spouting off other plans. She keeps remembering and wants to go to a place called “Beacon Point,” and while Monroe won’t show his cards, it’s clear the name means something to him.

But that ends up being the least of his worries. Within hours, there’s a shadowy group following them and trying to kill Alyssa. Could this have something to do with her parents being murdered? Monroe is forced into the role of protector, but much worse, into sharing time and space with this shell of a body that looks and acts so much like his wife. He knows it’s not her. He knows his duty is to bring translations in, not protect them. But he can’t help but fight for this woman, even if it’s not the woman he once loved.

Like I said above, The Translation is similar in a lot of respects to Blade Runner, most notably in tone. It’s a dark dreary future where most of the people are just trying to make it through the day.

But I think what separates The Translation from other movies is the intriguing love story at its core. Here’s a man who worked so hard to get over the surprise death of his wife, and now he’s forced to look her in the eye every second of this harrowing journey. We sense that a part of him wants to give in, wants to believe that she is, indeed, his wife. But he knows that logically that’s impossible. And it’s this central conflict that drives the story.

I also like the pace of the script. Every time you think Monroe and Alyssa are okay, they’re immediately back on the run again. It’s almost like The Bourne movies stumbled into a Blade Runner shoot – the best of both worlds.

But that world isn’t perfect. I loved Monroe but I thought Alyssa strayed from what made her so endearing at times. She’s best when she’s tender, curious, innocent, like a child. But after she starts learning the truth, she becomes angry, almost violent, and it was a little too out-of-character in my opinion.

The opening act is also an issue. And it’s not that I don’t recognize the challenge in writing it. Normally, your job in the first act is to set up 2 things: your plot and your characters. But when you write a sci-fi or fantasy film, you have to set up both those things *in addition to* your sci-fi world. In other words, you have to smoosh 33% more information into the opening 25 pages. As a result, your first act will feel jumbled or dense – not unlike you’re reading the Encyclopedia Britannica. That’s what it felt like here for me.

In addition, I thought some of the chase scenes could’ve been more imaginative. There’s a great car chase early on where Monroe is trying to elude the bad guys after Alyssa’s lost her breathing mask (worn until translations can breathe in the real world). The combination of being shot at from the outside and Alyssa dying on the inside made for an intense sequence. But after that, the chases become a little too “been there, done that.” And this is something I tell writers a lot. There’s a chase scene in almost every single movie ever made. So you can’t take short cuts when write your own. You have to try and be original.

In “Déjà vu,” (one of the biggest spec sales ever), they had a car chase where a character in the present is chasing a character in the past. The execution was shoddy on-screen but the point is, they were thinking outside the box. They were trying to do something different (I also have a feeling that that scene was a big part of why that script sold for so much – talk about delivering on the promise of the premise!)

Despite these problems, I really dug The Translation. I always go back and forth on which act is most important, but after reading this script, I’m reminded that the second act is probably the most important act in the script. It’s where you deal with your central conflict (in this case, the relationship between Monroe and Alyssa) and if that central conflict isn’t compelling, the reader gets bored and won’t give a shit what happens in the end. I thought the second act here was really strong and what separated The Translation from the rest of the competition.

Script link: The Translation (proper draft now up)

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Sci-fi pieces are tough, especially when they take place in a distant future or a far off land. Some writers try and weave the key details of their world into the opening act organically, like Aaron does here in The Translation. But this is really hard to do. A much cleaner method is to use a TEXT CRAWL or an OPENING VOICE OVER. What these do is they get the pertinent information about your world out of the way so you don’t have to spend precious story time dealing with it. The most obvious example is Star Wars, which explains its world to you in the opening crawl. Jake Sulley gets us up to speed in Avatar right away via voice over. Still another method, and probably the most viewer-friendly, is to open with a scene that acts as a setup to the world. In “The Fifth Element” for example, we have this entertaining opening sequence in the Egyptian pyramids that sets up the whole backstory for the “fifth element,” so we don’t need to wonder what the hell everyone is talking about later on. Whatever the case, consider using the first minute or three of your story to lay out your sci-fi world via text or voice over so you can use your opening act to do what it’s supposed to do – tell the story and entertain us!