Search Results for: star wars week

Guess what time it is? It’s time to venture into the SECOND ACT!

NOOOOOOOOOOO!!! you say.

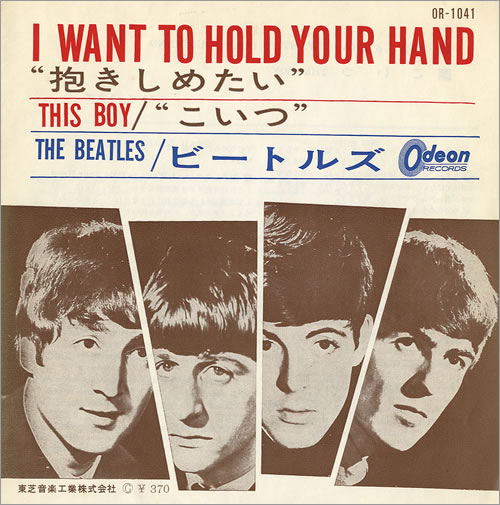

Don’t worry, my screenwriting salsolitos. Just like The Beatles, I’m going to hold your hand.

For those of you new to the site or you infrequent visitors, I’m doing a 13 week “Write a Screenplay” Challenge, where I guide you through the process of writing a screenplay step by step. If you missed the first few weeks, you can find them here:

As of today, you should have written 21 pages. That means you’ve completed your inciting incident (located near page 12-15) but are not quite at the end of your first act (page 25). So today, we’ll be covering the break into Act 2, as well as the first sequence of Act 2.

Now I heard some grumbling last week about 3 pages a day being too difficult. Come on, guys. Seriously? That’s one scene. You only have to write a single scene. You’re telling me you can’t write a scene in a day??

Maybe this will help. Brendan O’Brien and Andrew Jay Cohen said that when they were trying to figure out their script, “Neighbors” with director Nicholas Stoller, they’d pitch him a bunch of directions they could go, thinking he’d pick one and let them go write it.

Instead, Stoller would say, “Well let’s try that version right now.” “What do you mean right now?” they’d ask. “Let’s sit down and write it and see if it works?” “You mean write the script… now??” “Yeah.” And they’d sit down and write the whole thing over a few days. If it didn’t work, they’d try a different take.

The point is, you’re capable of one scene a day. Don’t be a perfectionist. Just write.

Okay, on to this week’s challenge. You’ve got between 4-8 pages before the end of your first act. If your hero is in a refusal of the call situation (Luke Skywalker claims he can’t join Obi-Wan because he must stay and help his Uncle on the farm), this will be the last bit of resistance your character experiences before accepting that they have to go on their journey (pursue their goal).

If your hero isn’t refusing the call, this is the last few pages of logistics before they pursue their objective. Indiana Jones don’t refuse no call. He just packs his bags and prepares for the fun. If your character doesn’t have any say in the matter, the forces of the story will simply kick them out on their journey, much like a bird kicks its babies out of the nest to see if they can fly. Tough love, amirite?

Now in some cases, a journey is literal. Rey’s journey in The Force Awakens takes her across the galaxy. Tom Cruise and Dustin Hoffman take a road trip to Vegas in Rain Man. Joy has to travel deep into the recesses of Riley’s mind in Inside Out.

Other times, it’s more symbolic. As long as your character is constantly pursuing something, even if they’re stationary, it’s considered a journey. To use the aforementioned Neighbors as an example, our heroes may be inside the same house the whole movie, but their “journey” consists of trying to get the frat next door kicked out.

So the first 15 pages of the second act are a unique time in a script. Your heroes are going off on their journey, but since we can’t throw the kitchen sink at the audience right away, this section tends to be more of a “feeling out” period for the characters. Maybe they’re feeling out each other (“Bad Grandpa”) or feeling out the situation (In a heist flick, the characters might scout out the bank they’re planning to rob, or the team they’re trying to recruit).

The late Blake Snyder, whose book “Save The Cat!” is somehow still the best selling screenwriting book out there despite Scriptshadow Secrets being available, famously termed this section, “Fun and Games.” Since Blake mainly wrote comedies, this was meant to define the period in the script where you showed off the promise of your premise.

The best example of this is probably super-hero origin stories. This is the moment when Spider-Man or Ant-Man first get their powers and play around with them. But it can also be applied to other genres. In Jurassic Park, it’s seeing the dinosaurs for the first time. In The Equalizer, it’s when Denzel starts administering justice on the locals.

If all of this is confusing, however, or it doesn’t feel like it applies to your movie, don’t worry. There’s a backup. What’s that backup?

SEQUENCES

Divide your script into a series of eight 12-15 page sequences. You’ve already finished the first two sequences. That was your first act. Now you’re on your third. You have to fill up 15 more pages. The easiest way to do this is to give your characters an objective they have to meet by those 15 pages. That way, you don’t have to worry about this giant chasm-filled void of a second act. You only have to write 5-7 scenes getting your hero to the end of that sequence goal.

A good example is the Mos Eisley sequence in Star Wars. We’re officially on our journey into the second act. What’s the goal here? The goal is to get a pilot and get the fuck off this planet, since the Empire is chasing us. We experience a series of scenes where our characters come to Mos Eisley, enter a bar, look for a pilot, get a pilot, head to the ship’s hanger, get chased by stormtroopers, then leave. That’s a sequence right there, folks. That’s all you have to do.

You can even use this for non-traditional scripts. Room is a movie that’s basically two long acts. It’s divided in half. But if you look closer, you’ll notice that there are sequences to give the story structure. For example, the fourth sequence of that movie (which would roughly be page 40/45 to page 52/60) is Ma (Brie Larson) planning the escape. That’s a sequence folks. It’s got a goal. It consists of a series of scenes. This stuff isn’t rocket science.

Gravity is a great movie to study for sequencing. It’s evenly broken down into a series of sequences where Sandra Bullock constantly has to get to the next destination, which usually takes between 10-15 pages (no, that is not an excuse to procrastinate!).

So that’s this week’s challenge, guys. You have to get 15 pages into Act 2. Seeing as we finished on page 21 last week, that means you only have to write 19 pages this week, which is LESS than 3 pages a day. Which means no more complaining. I’ll see you next week, with 40 total pages completed. And that’s when we head into the HEART of the second act. Ooh, I can’t wait for that. And by “can’t wait,” I mean, “Shit, that’s going to be terrifying.” Seeya then!

For the next three months, every Thursday, I will be guiding you through writing a feature-length (110 pages) screenplay. Why are we doing this? A few reasons. For new screenwriters, it’s a chance to learn how to write a screenplay. For experienced screenwriters, it’s an opportunity to learn a different approach to writing a screenplay. And for every screenwriter, it’s an opportunity to light a fire under your ass, keep you moving, and have a finished script in your lap in just 90 days.

We have three months to achieve this, which equates to roughly 13 weeks. Each week I’m going to give you a task, which you will need to finish by the following week. I’m going to need, at minimum, two hours of your time a day. However, the more time you can contribute to the cause, the better. More time means more thought, more trial and error, more swings, which means an overall improved product.

One of the biggest pushbacks I expect to encounter in this exercise is writers saying, “Well I don’t do it that way. I do it a different way.” Tough. This is about trying something new. It’s about going outside of your comfort zone so you can grow. I don’t expect you to write every script this way from here on out. But I do expect you to discover some new methods you’ll be able to use in future scripts. So don’t complain. Just do it.

The plan is to write both a first draft and a second draft. Afterwards, the best scripts will be chosen for a tournament. You do not have to participate in the tournament if you don’t want to. It’s merely there to incentivize you throughout your journey. Those tournament scripts will be put up for critique by the Scriptshadow Faithful, who will vote for the best script each week. The feedback they give you, you can then use for further rewrites to improve your script for the later rounds.

Are we ready? Okay, let’s get to it.

First and foremost, you need a concept. We’ve been trying to come up with those for the last two weeks. Guys, I tried to get through all the loglines you sent me but there were just too many. I’ll attempt to rate a few more today but don’t hold your breath. If you didn’t get any feedback, you’ll have to go with your gut and write the idea you like best. And really, let’s be honest. You were going to write your favorite idea anyway. :)

If you didn’t participate in the last two weeks, you’ll need to come up with a concept and logline pronto. Check out last week’s post, as well as the comments, and you’ll get an idea for which concepts tend to work best. Once you’ve identified your concept, it’s time for the first task. And the first task is one that 50% of screenwriters detest. I DON’T CARE. This is your week 1 assignment.

OUTLINE AND CHARACTER BIOS

For those of you who want to start writing your script, TOUGH. Unless you’re a genius, the screenwriter who jumps into his script immediately runs out of gas by page 45. Oh, they won’t admit it. They’ll keep writing. But deep down they know they’re lost. This week’s assignment is designed to prevent that from happening.

DAYS 1-3 – THE OUTLINE

There are six main points you want to identify in your outline. But before we get to those, let’s go over the basic blueprint of a story. A protagonist is breezing along in their life. Then something happens that jolts the status quo. This thrusts them onto a journey where they try to achieve a goal. They encounter lots of obstacles and uncertainty along the way. Then, in the end, they somehow pull off the impossible and achieve their goal (or fail!).

We’re writing 110 pages here. So you’ll break your outline down into Act 1 (roughly pages 1-27), Act 2 (roughly pages 28-85), and Act 3 (roughly pages 86-110). Your scenes will average between 2 and 3 pages long. That does not mean every scene will be 2 or 3 pages. It means this is the AVERAGE. Some scenes may be 7 pages. Others may be half a page. In the end, you’ll be writing between 45-60 scenes.

The more scenes you can fill in for your outline, the better. But the only ones that are required for next week are these six. If you can figure out more, great. But these are the essentials.

The Inciting Incident (somewhere between pages 5-12) – The Inciting Incident is a fancy way of saying the “problem” that enters your main character’s life. For Raiders, that’s when the government comes to Indiana Jones and says they’ve got a PROBLEM. Hitler’s looking for the Ark of the Convenant. You, Indiana, need to find it first. Or, more recently, in The Revenant, it’s when Leo is mauled by a bear. Everything is irrevocably changed in his life after that incident.

The First Act Turn (page 25-27) – The first act turn is when your main character will start off on his journey to try and obtain whatever it is he’s trying to obtain. So what happens between the inciting incident and the first act turn? Typically, a character will resist change, resist leaving the comfort of his life. But most of the time it’s just logistics. We’ll set up what needs to happen, how they plan to do it, how impossible the task will be, etc. It all depends on the story.

The Mid-Point Twist (page 50-55) – If your story moves along predictably for too long, the reader will get bored. The Mid-Point Twist is designed to prevent that from happening. It changes the rules of the game. And there’s a bit of creativity to it. It could be an unexpected death. It could be a major betrayal. It could be a twist (Luke and Han get to Alderran, but the planet they’re going to has disappeared!). The point of the Mid-Point Twist is throw your story’s planet off its axis.

The End of the Second Act (page 85-90) – This will be your main character’s lowest point. They likely just tried to defeat the villain or the problem and failed miserably. Along with this, everything else in your character’s life should be failing. Relationships. Their job. Their family. It’s all falling apart. Your hero will be AT HIS LOWEST POINT. Hey. HEY! Stop crying, dude. It’s just a movie. He’s going to get back up and kick ass in the third act. But right now, it looks like he’s fucked.

The Early Second Act Twist (page 45) – We’re going backwards here only because I wanted to get the important plot points down first. Once you have those, figure out page 45. Basically, page 45 will be 15-20 pages into your second act, typically where most writers start running out of ideas. You need to add some sort of unexpected moment here. Something that lights a fire under your plot. It’s not going to be as big as the Mid-Point Twist. But you can’t have 30 straight pages of the same pacing. You have to mix it up. The Early Second Act Twist in The Force Awakens occurs when Rey and Finn get captured by Han Solo. Notice how Han’s entrance into the story takes everything in a different direction.

The Late Second Act Twist (page 70) – This is the same idea as all the other “twists” we’ve been talking about. If you mosey along for too long without anything new or different happening, the reader gets bored. You need to be ahead of the reader, always coming up with plot points that they didn’t expect. I’ve seen writers use The Late Second Act Twist to kill off a character. In Frozen, it’s the moment where Hans reveals to Anna that his entire courting of her was a sham designed to take over her kingdom.

Once you have these six key moments in the script mapped out, you’re in great shape. Why? Because now you always know where you’re going. You always know where you’re sending your characters, which will give your script PURPOSE, something people who write randomly and without an outline rarely have. And don’t worry. These moments are not set in stone. As you write the script, you’ll have new ideas, and these key points may change. That’s fine. But by having something in place initially, you’ll be able to write a lot faster.

It should also be noted that not every story will follow this path. Not every script’s structure is based off of Raiders of The Lost Ark. I get that. Still, you want to think of these moments in a script as CHECKPOINTS. Whether you’re writing the next Star Wars or the next Magnolia, every 15-20 pages, something needs to happen to stir the pot. So if you’re going to take on something unique, no need to fret. Give yourself those 6 checkpoints so that your script is moving towards something.

DAYS 4-7 – CHARACTER BIOS

I know. You HATE CHARACTER BIOS. Look at it this way. Remember when your parents told you to eat your vegetables but you never understand why when Captain Crunch and pop tarts tasted so much better? Then when you hit adulthood and you were 40 pounds overweight, you looked back and thought, “Hmm, mom and dad may have been right about that one.” Well, the same thing’s going on here. Character bios may not be fun. But you’ll thank me for them later.

What you’re going to do is write a character bio every day for your four biggest characters. One of those characters will likely be your villain. Here are the things I want you to include in each bio. Try to get between 1500-2500 words for each character.

1) Their flaw – Figure out what’s holding your character back at this moment in their life, the thing that’s keeping them from reaching their full potential as a human being. Stick with popular relatable themes. Selfishness, egotistical, stubbornness, fear of putting themselves out there, doesn’t believe in themselves. You may not explore this flaw in the movie. But it’s good to know, as it will be the main thing that defines your character.

2) Where they were born – A lawyer from the projects in Chicago is going to talk and act differently than a lawyer from the upper crust of a rich East Coast suburb.

3) What their family life was/is like – Our relationships with our siblings, but in particular, our mother and father, influences our personality and approach to life more than anything else. Know your character’s relationship with each and every family member.

4) Their school history – Were they a nerd? The popular kid? A drug dealer? An athlete. Our school experience, particularly high school, affects who we are and how we act for the rest of our lives. So the more you know about this period in your character’s life, the better.

5) Their work history – Work is 50% of our lives (for many of us, a lot more). It has a big effect on who we are. So you want to establish what your character used to do before they got their current job, and also the events that led to them getting their current job.

6) Highlights of their life – This is basically everything else, the character’s highlight reel, if it were. When they lost their virginity, any devastting breakups, their highest points, their lowest points. Just let loose here and use this section to discover what your character’s life has been like.

And that’s it! You’ve completed your weekly task. If you finish ahead of time, go back to your outline and fill in the areas between the major plot points. The more scenes you can outline ahead of time, and the more detail you can add to those scenes, the easier it will be to write the script when that time comes. Okay, all of this starts RIGHT NOW. So what are you waiting for???

Is today’s script a spiritual sequel to yesterday’s entry? They’re both about bubbles. As long as we’re on the topic, David Lynch should ditch Saliva Bubble and direct this. It would be EPIC!

It’s finally here! The culmination of Weird Scripts Week! On Monday you saw us deal with James Bond and robot sharks. On Tuesday, talking cows. On Wednesday we went into the mind of a man living his own musical. Yesterday’s script was about spit. But today is truly the pinnacle of weirdness. Get the drugs out and enjoy…

Genre: Biopic

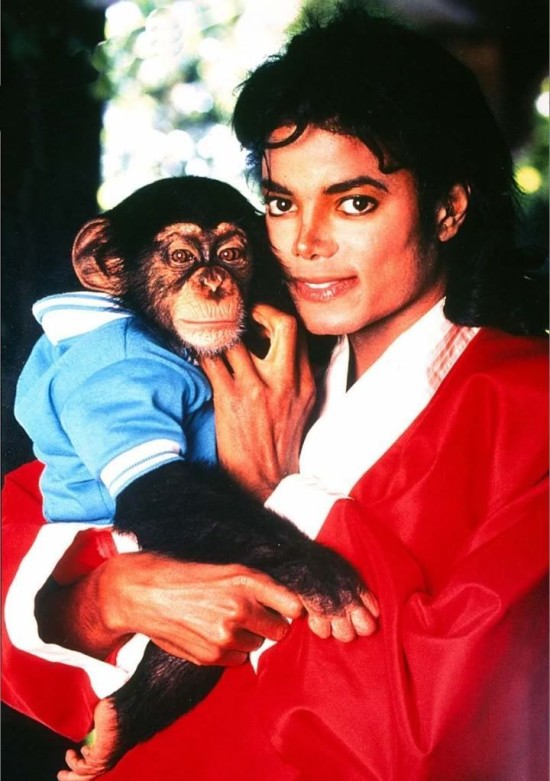

Premise: I told you I was saving the craziest for last. How ‘bout a biopic of Michael Jackson told through the eyes of his chimpanzee, Bubbles!

About: This script went out earlier this year, and while it’s got about as much chance of getting made as Uwe Boll does helming a Star Wars movie, it wins the “Oh I’ve gotta read this” premise of the year award. While writer Isaac Adamson doesn’t have a legendary list of IMDB credits, he’s far from a stranger to Hollywood. His first novel, Tokyo Suckerpunch, has been in development for years at Sony. If Allan Loeb’s Collateral Beauty is ending up number 1 on this year’s Black List like everyone is telling me it will (I still haven’t read it – saving it for when I can relax and enjoy), my guess is that Bubbles ends up at number 2.

Writer: Isaac Adamson

Details: 122 pages

Isaac Adamson, I don’t know who you are. But you’re a genius, my friend.

This is one of those ideas you and your screenwriting friends come up with at 3 in the morning after a night of drinking, laugh uproariously about, then after the laughter’s died down, you proclaim, “No, but really, what if I ACTUALLY wrote it?” And then everyone laughs and says, “Yeah, you should TOTALLY write it.” “Oh my God. Yeah. That would be hilarious!”

And then the next morning through the foggy haze, before you’ve emptied your loose change on three Sausage McGriddles, you remember your crazy premise about telling Michael Jackson’s story through his chimpanzee’s point of view and you grimace and say, “Was I bananas??”

Isaac Adamson must have put down the McGriddles because he not only wrote it, he committed to it. And really, that’s the only way to do it. When you come up with a gimmick premise, you quickly find that there’s nothing to really say past page 15. You’ve introduced the gimmick. What’s left to do?

If you want to extend an idea like that into feature length, you have to embrace and treat the characters like real people, with real problems and real conflicts. And with the exception of Bubbles’ thoughtful meanderings, that’s exactly what Adamson does.

“Bubbles” opens up with a voice over from Bubbles himself. It’s present day and Bubbles lives in a cage along with a number of other animals. He’s not thrilled about it, but as he explains to us in the coming pages, he’s not sure he prefers his previous life either.

Flash back to 1985, the height of Michael Jackson’s fame. Michael has just come out with Thriller, the biggest album of all time! And he wants more. He wants his next album to do the impossible – to sell 100 million records.

He also doesn’t want to be alone during that journey. When you reach that kind of fame, it’s difficult to find friends. This is usually where your family comes in, but Michael’s family, particularly his evil father, Joe, is more interested in using Michael’s fame to jumpstart their own careers than support and love their son/brother.

So Michael buys a monkey! Whereas Michael is childlike and simplistic, Bubbles is a cross between an overly-educated Oxford graduate and a Roman philosopher. He ruminates about Michael’s life choices with such voice over lines as: “Should I have been alarmed that the notion of myself as sovereign provoked such laughter from The King? Or that seeing me festooned in the regal accouterments induced only befuddled discomfiture from these hirsute gentlemen of New Jersey?”

Michael and Bubbles become fast friends, and Bubbles takes pride in that a man who everyone refers to as “The King” has made him his prince. We follow the two through Michael’s struggles to make that impossible 100 million copy album, and during that time, Bubbles, too, becomes a celebrity (particularly in Japan).

But things start to change when Michael moves into Neverland Ranch, a place where he’s finally free of his blood-sucking family. Neverland brings with it many children, distracting Michael from Bubbles. And when one particular child, Jordan Chandler, becomes Michael’s best friend, Bubbles feels like he’s on the outs.

When Jordan’s father (who happens to be a screenwriter!) threatens to sue Michael for molesting his child, Michael’s kingdom, as well as his friendship with Bubbles, unwinds to a point where it can never be salvaged again.

We always talk about how once you find your idea, or your subject, you need to find your angle. Your angle can take what’s, at face value, a generic idea, and bring it to life. I mean, imagine if this was just another Michael Jackson biopic. Adamson would be lucky if Lifetime requested it. By exploring Michael through the angle of his pet chimpanzee, we get a completely unique perspective of the pop star. What was once dull is now fresh. This was the first great choice Adamson made.

The second was to treat everybody here like real people. Once you treat your characters like real people, your reader will actually invest in them. This doesn’t work if you play everyone as a farce. This was my problem with yesterday’s script. Nobody in One Saliva Bubble was real. They were all goofy gimmicks, and therefore we could never get inside of them. For a short movie, gimmicks are fine. For a feature, though? If you’re going to ask someone to sit still for two hours? You need to give them something to invest in.

With that said, I was surprised how far Adamson went down this path. I was curious how he would treat the child molestation charges on Michael but he faces them head on – to the point where they’re the climax of the story (okay, that was unintended, I swear). And because we’d invested so much in Michael by this point – seen how everyone around him existed only to take advantage of him – we really cared about what happened next.

Bubbles the character is a mixed bag. His high-brow observations do get a little tedious at times, but more often than not, they’re fun. For example, when Michael leaves the house only to come back with bandages on his face, Bubbles assumes that his “King” must have gone off to battle, defending his kingdom and defeating his many foes.

And it’s not like he’s unconnected to the plot. His jealousy of the people who hang around Michael are what drive his actions, and it’s why (spoiler), in the end, he’s forced to leave Neverland Ranch.

My issues with “Bubbles” are tempered by the commitment to the idea, but I did have a problem with the script length. This is the kind of premise you want to get in and out of faster than a Hollywood and Vine escort. There’s an entire “Michael in the UK” section that Bubbles doesn’t even participate in that easily could’ve been excised.

I also wished there was more Joe. When you have any script that doesn’t fit nicely into a movie-like structure (which is the case with most biopics), a great villain can be a huge help. You get the audience so wound up about the antagonist and so obsessed with seeing his demise, that they don’t even notice the movie’s flying by. From everything I’ve read, Joe Jackson is a terrible person, especially to Michael. So I would’ve loved to have seen that conflict explored more.

This script will probably never sell and most definitely will never be made. But it does so much more. It shows Hollywood that you’re not afraid to think outside of the box. And while Hollywood loves its formulas, the people who work within it secretly pain for these new voices, for new ideas, for new angles. Those angles may never make it to the big screen, but those writers are admired and called upon again and again for potential writing assignments because they showed that they could go where other writers were too afraid to. So while Bubbles isn’t a perfect story, it’s perfect in its uniqueness, which is why I’d be an idiot not to call it impressive.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[x] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: As simplistic as this sounds, if there’s one thing I’ve learned from this week, it’s that if you want to write something weird, utilizing animals in some unique way is a good place to start. Especially if you want to make the Black List, which thrives on celebrating weird stories. High-ranking Black List scripts The Beaver, The Muppet Man, and The Voices all focused on animals in some weird way. Add Bubbles to that list.

Get Your Script Reviewed On Scriptshadow!: To submit your script for an Amateur Review, send in a PDF of your script, along with the title, genre, logline, and finally, something interesting about yourself and/or your script that you’d like us to post along with the script if reviewed. Use my submission address please: Carsonreeves3@gmail.com. Remember that your script will be posted. If you’re nervous about the effects of a bad review, feel free to use an alias name and/or title. It’s a good idea to resubmit every couple of weeks so your submission stays near the top.

Genre: Martial Arts/Asian Epic

Premise (from writer): A rebellious-minded woman in ancient China seeks the help of Shaolin to save her village from a love-obsessed General and his bloodthirsty Captain.

Why You Should Read (from writer): I’m a 44 year-old soccer mom who secretly loves kung fu. There are a lot of us out there – sneaking into Man of Tai Chi after the lights go down; snagging a $5 copy of Ip Man at 2nd & Charles so the Netflix queue stays “clean.” Every day we chauffeur, tend, cook, coordinate and cajole while desperately longing to settle things with a swift scorpion kick.

“Wars of Eternal Spring” took shape after the perfect storm of a “fu-binge,” Robert Downey, Jr. interview and spur-of-the-moment Google on “Wing Chun style.” Not long afterwards I read that Keanu Reeves was looking for his “next story” to direct. Filling needs is practically my raison d’etre these days, so the off-hand words of a man I’m never likely to meet were more than enough to fuel a feeble flame and get writing.

I gave myself a year. I even told my therapist. In between writing bouts I read screenplays and books on creative processes, story structure and character development. I searched high and low for a critique group. All the while I worked, re-worked and started to get a sense of how much time, realistically, writing anything worthwhile takes.

I believe that the biggest room in the world is the room for improvement. Your professional, experienced review would go a long way toward helping me do that. Thanks in advance for your consideration.

Writer: Elizabeth Barilleaux

Details: 100 pages

So when Wars of Eternal Spring won the Amateur Offerings, I’m not going to lie in being a little suspicious of the voters’ motives. A soccer mom who loves kung-fu may very well be every male screenwriter’s fantasy. I actually think it would be hilarious if Elizabeth was a guy and made this persona up just to stand out a bit more. And you know what? If that were the case, I’d say “well done.” In this business, you gotta use every little trick in your bag to get noticed.

But when the script hits Amateur Friday, it doesn’t matter if you’re a pimple-faced geek who plays the accordion or a European runway model. I’m judging the script on the content. I will say this though. It’s pretty cool to read a genre that’s never been reviewed before on Scriptshadow. Let’s see what happens!

Poor Wing Chun. She’s one of the few women in ancient China who’s been taught martial arts. And while that may make a woman hot stuff today, it made them the definition of unattractive back then. In fact, after taking down a thief for stealing apples from a fruit vendor, even the fruit vendor tells Wing Chun to screw off. You’re welcome very much!

Wing Chun’s life changes when an army from the Qing Dynasty moves into her village to sniff out possible Ming hiding nearby. The army is led by the handsome General Jin, who’s immediately taken by the unorthodox Wing Chun. His second in command, however, Ganbaatar, is a little less welcoming, and is convinced that Wing Chun’s fighting skills are a result of her working with the Ming.

Ganbaatar’s wrath becomes so intense that Wing Chun is forced to flee into the mountains, where she searches out the Shaolin Temple, a place where she’s wanted to train all her life – despite knowing they would never train a woman. When she gets there, however, she finds that the Shaolin Temple has been destroyed by the Qing.

Luckily, she meets an old hermit who used to be a Shaolin, and after some initial resistance, the hermit decides to train her. In the meantime, Ganbaatar is running roughshod all over the village, and the villagers, as well as Wing Chun’s family, find themselves in danger. Wing Chun and the hermit (who may not be who he appears to be) will need to come back to the village to save the day – a task as ridiculous as it is impossible.

Let me preface this by saying I’m not really into these kinds of movies. I like kung-fu when Neo’s doing it. But wire-fu in Ancient China ain’t my cup of tea. However, if you’ve been paying attention to Scriptshadow for awhile now, you know that the fighting and the chases and the action are just the icing on the cake. The CAKE is the characters. If you can make us fall in love with your characters, it doesn’t really matter what they’re doing. They could be washing windows, breakdancing, spelunking, or fighting in Ancient China. We’re going to care.

These characters – and really this entire script – is written with such skill, I’m shocked Elizabeth isn’t already represented. Our main character, Wing Chun, isn’t just a great character. She could be an iconic character if this movie is ever made. Elizabeth captures the travesty of being a unique woman at a time when individuality wasn’t accepted from that set of chromosomes. Wing Chun’s underdog story rivals that of William Wallace in Braveheart and Maximus in Gladiator. And hell, Neo too! You can’t help but root for the girl.

And all the characters here feel authentic. They all have fears and flaws and pasts, and in a way that doesn’t dominate the story. A lot of times I’ll see writers give their secondary characters big fat backstories, halting the script in the process, resulting in boredom. Elizabeth is able to paint every single character with depth, but never in a way that slows the story down. This script is only 100 pages, yet it feels like this vast epic. It’s really impressive.

Take General Jin for instance. He’s this lonely man who dreams of a softer life than the one the military provides. The occupation of this village for him has nothing to do with searching out the Ming. He uses it as an excuse to settle down – to live the peaceful life he’s always wanted. At the other extreme is Ganbaatar, who’s lived this reckless violent life, and who doesn’t trust a soul. It’s rare that a straightforward villain doesn’t feel “on-the-nose,” but Elizabeth manages to make Ganbaatar both evil and real – a rare feat.

I loved some of the twists and turns in the story as well (spoilers). The monk secretly being Ng Mui came out of nowhere – and it was one of those pleasant surprises that most writers tend to force. Because this script was so beautifully written though, it was like, “Of course she was pretending to be the hermit! It makes perfect sense!”

I loved how Elizabeth plucked little ideas out of the fairytale universe as well, such as the evil stepmother, who was great. And it was fun to see her use The Hero’s Journey in a way where you knew she was using it, yet it never forced itself upon the story. So many writers use a structure (basic 3 act structure, sequencing, Blake Snyder beat sheet, Hero’s Journey) and force it on the story. It takes a real pro to use a structure as a guide, but have that structure be invisible in the final product.

But I think the thing that most impressed me was the overall quality of the writing. Usually you have a writer who’s good at one or two things and then bad at a few others. Here we had someone who understood the history of this world, who understood the depths of this genre, who knew how to write powerful and memorable characters, who nailed the dialogue (not easy in a period piece), who nailed the structure.

And on top of all that, it was just a good story. I liked how, even though the first 50 pages were stuck in the village, Elizabeth kept the tension high with conflict. If you’re going to be in one location, you need to include a ton of conflict between the characters. So we have Ganbaatar who doesn’t trust Wing Chun. We have General Jin who falls for Wing Chun. We have the villagers who don’t want their village occupied anymore. There’s just a general discontent everywhere, so we’re not even aware that the story isn’t technically moving yet.

And then, Elizabeth wisely moves to a more traditional tale in the second half of the story, where we have a big goal – find the Shaolin Temple and train. And, of course, like we were just talking about a few days ago, Elizabeth throws a shitload of obstacles in the way. The Qing catch up to Wing Chun in the mountains. The Shaolin Temple has been burned down once she gets there. It was just a really compelling story led by a really compelling main character.

The only issues I had were minor ones. From what I understood, Young Li was Wing Chun’s real brother and Fan was her step-sister. So Young Li wanted to marry Fan? So he’s marrying his step-sister? Was that something that was legal or kosher back then? Cause it seemed a little incestuous to me. Also, there were a few scenes where it seemed like Young Li wanted to marry Wing Chun. You were just a little too vague and it led to confusion.

Also, I was frustrated at first about all the sides. I didn’t understand who the Qing was, who the Ming was, and how the Shaolin fit into it all. So when, for instance, Ganbaatar would get angry at anyone who sided with the Shaolin, I didn’t know what that meant, since I thought the Shaolin were neutral. I know a quick title card explaining these things at the beginning of the screenplay might invade on the “purity” of the story. But it’s something that could help people not steeped in Chinese lore.

Finally, we just need to break up a few of these chunky paragraphs (anything over 4 lines), particularly in the last act, when the reader’s eyes should be moving more quickly down the page.

But yeah, this is high-class writing here. We don’t see this much on Amateur Friday. I have to give it to Elizabeth. She’s set a high bar for all future Amateur Offerings this year. Great job!

Script link: Wars of Eternal Spring

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[x] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Honestly, I think my biggest takeaway from this script is the power of writing about something you’re passionate and knowledgeable about. Nothing comes through more than when you love your subject matter. You’re always going to go that extra mile to get it right. Had someone who was only a casual fan of Ancient Martial Arts movies written this, there’s no way it would’ve come even close to Elizabeth’s script. So keep that in mind when you’re coming up with your next screenplay.

Genre: Sci-fi

Premise: (from me – based on limited info) A group of shuttle astronauts find the world scorched and dangerous upon returning home.

The setup: The year is 2045. The space shuttle Excalibur has completed its routine satellite conservation mission only to find that the Earth has perished overnight- crystal blue waters replaced by dark crimson, white clouds now a gory hue, continents indiscernible. After much debate, and resources depleting, they have no choice but to go down. They arrive and

find themselves in a deserted wasteland, dead and burnt cities, a graveyard civilization. Lifeless.

Writer: Rzwan Cabani

Details: 7 pages

I think one of the hardest things about scenes is that, if you’re doing your job right, you’re trying to cram key information into every one of them, as you want each scene to push the story forward and tell us a little bit about your characters. The problem is, when writers do this, they often go overboard with this information, or they convey it in the wrong way, stilting the scene and making it more about information and character development than pushing the story forward.

And that’s the trick. First and foremost, every scene should be about PUSHING THE STORY FORWARD. All the other stuff should be hidden inside of that, instead of taking precedence. There are exceptions of course, and this approach will be treated differently in an action movie than, say, an indie character piece. But for the most part, it doesn’t matter what kind of movie you’re writing. The scene should exist primarily to push your characters towards their current objective, not bore us with information.

This happened with the most recent amateur script I read. A large number of scenes existed only to show two characters in a room talking about things that did happen, were happening, or were GOING to happen. Information-heavy scenes like this can be the death of a screenplay (and one of the easiest ways to spot amateur writers). In general, you want your characters chasing goals or leads or objectives that have them moving towards the next plot point. Along the way then, you cleverly drop in that information (what’s often called “exposition”), so it’s not the focus of the scene, but rather a secondary aspect of it.

I’d say a good 50% of the scenes sent in were dismissed for this reason. Characters weren’t going after anything (like yesterday, where our character was trying to get his girlfriend back) or reacting to anything (like Monday, where our characters had to avoid a swarm of aliens). They were just talking about other characters, or about the plot. And unless there’s something compelling that needs to be hashed out between the characters, or just a ton of conflict, talking scenes are borrrrrring. Never forget that.

Today’s script follows astronauts, Max, his love interest Amanda, Russian Sven, and the grizzled vet, Berkely. The four have just landed back on earth after being in orbit for awhile and boy, are things different. The planet’s been scorched. It doesn’t look like there’s any more water. After looking around from the safety of the ship, they spot a man sitting in this barren field, facing away from them. They leave the ship and go to him, only to find out he’s a decoy. It’s a trap. They hear something big and angry emerge out of nowhere and they start running. They get back inside the ship, only to be repeatedly rammed by whatever this is. Just as it looks like their ship is about to break, the banging stops, and a man in a cloak emerges from the shadows, beckoning them to open the door. He can help.

There were a few things I liked about this scene. First, there’s suspense. What the hell happened to the earth? Next, there’s this guy just sitting out there in the desert. Who is he? Why is he facing away from them? More suspense! They approach the guy. What’s going to happen?? We don’t know but we want to find out!

And what we find out is that he’s a decoy. They’ve been lead out here on purpose. Knowing they’re in trouble, they run back. And what I loved is that Rzwan did NOT SHOW the huge monster chasing them. We only HEARD it. This is an indication to me of a writer who knows what he’s doing. Amateur writers tend to blow their load and be completely obvious with every situation they write. They would’ve shown this monster in an instant, erasing all the mystery behind it. Because we don’t know what it is, we must imagine the monster ourselves, just like our characters. And just like our characters, our assumption is probably a lot scarier than whatever the writer could’ve come up with.

This is followed by the arrival of the man in the cloak, which creates another “mystery box” that is intriguing enough to get us to the next scene. Add all that to some really slick writing (Rzwan’s prose is lean, crisp and quite descriptive) and you have yourself a nice little scene.

Frustratingly, despite it being better than the majority of scenes that were sent in, it wasn’t perfect. The arrival of the cloaked “person” in the chair wasn’t introduced clearly enough. I’m presuming we landed here in this huge barren landscape where we can see all around us. Nobody saw anything then?? Their first look around once they’d landed produced the same result. Nothing.

Then, all of a sudden, there’s just some guy sitting in a chair? How did they miss that?? Even worse, we’re never told how far away he actually is. Is he 10 feet away? Is he 500 feet? These things matter, particularly when we’re trying to figure how this figure who’s sitting on a chair in the middle of the desert can be missed.

Remember, one clarity error in a scene can KILL that scene. Every single little thing you were trying to accomplish, from the location to the setup to the characters, can be capsized by a single clarity error. And the truth is, we can’t always catch these. In our minds, because we can see the whole thing in our head, the setting is clear as day. So of course we’re likely to under-describe. On the flip side, if we over-describe the scenario and get TOO detailed, the scene gets bogged down in text and reads like molasses.

So you have to find that balance. All you can do is ask, “Have I made all the key elements to this scene clear to my reader?” And then, of course, before you send it out officially, you get a few people to read it and see if they understood it as well.

As for the rest of the scene, I like the mystery of Max (the cloaked man who approaches at the end), but a) I’m wondering how yet another character could’ve just appeared out of nowhere in this endless barren desert, and b) When I see cloaked people in deserts (which believe it or not I’ve seen a few of in the last few weeks via script reads), I immediately think of Star Wars. And when you’re writing sci-fi, you want to avoid stuff feeling too similar to the most popular films in that genre.

So to summarize, I liked the machinations of this scene. I liked what Rzwan was doing to create anticipation and suspense. I love how he didn’t show us his monster. But some of the details needed more explaining, like how people in chairs can just appear out of nowhere. And maybe we could’ve milked that build-up a little bit more. More discussion/arguments before going out to look at Chair Guy. More description of the eerie landscape. When you have a suspenseful situation like that set up, you want to milk the suspense!

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read (just barely)

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Information (exposition) should never be the focus of the scene. It should be a secondary directive only.

What I learned 2: If you can’t come up with a creature scary enough, don’t show it! Or only show pieces of it. Let the reader imagine what it is himself. The version in his head is probably a lot more freaky!