Search Results for: the wall

Today’s writer found a way into the business writing in a genre he was passionate about, despite that genre being a tough sell. Should you do the same?

Genre: Drama/Biopic

Premise: How a young unemployed Marlon Brando got his breakthrough role in the classic Tennessee Williams play, “A Streetcar Named Desire.”

About: Recently, unknown screenwriter Tom Shepard, who worked as a waiter, secured an assignment on one of the bigger projects in town, a biopic about Al Capone starring Tom Hardy (I erroneously listed this as a biopic about Al Pacino in my newsletter – now that would’ve been interesting). The details of the story are listed at Deadline. Basically, while he WAS a repped writer, Shepherd had yet to do anything in the profession. Then he wrote this script on spec, which got onto last year’s Black List, and I suppose they saw a complexity in the way he explored Brando they thought he could do the same for with Al Capone. We’ll have to wait and see if he got it right!

Writer: Tom Shepard

Details: 123 pages

I don’t know about these biopic scripts. I just don’t. I mean, it seems kind of like cheating. You just pick a famous figure in history and tell their story. Assuming you tell it competently, fans of that person will want to read it. I won’t want to read it. I need more to enjoy a biopic. In addition to a fascinating character, I need a fascinating story. Yet most writers writing biopics aren’t telling stories (which takes skill), but recounting a life (which takes only research). So I see this logline and I think….ehh, I already know what this is. I already know where this is going. Write a script about Michael Jackson, about Jim Morrison, about Gandhi, about Bruce Springstein. All you have to do is research the people you have yourself a script. But where’s the drama? Where’s the story?

Waiter Tom Shepard wisely took another avenue. He decided to tell the STORY of how Brando got his famous breakout role, the part of Stanley in “A Streetcar Named Desire.” It wasn’t a biopic biopic. It was a sneaky biopic focusing on a pivotal moment in the character’s life. Which, in my opinion, is the best way to do it. But did it succeed? Unlike 42, where I already knew the broad strokes of the story and was therefore never surprised, I have to admit I know nothing about Brando’s early acting career, and even less about how he got the role that turned him into a star. To be honest, I didn’t even know this WAS his first major acting role. So I was kinda curious how that all played out.

It’s 1947 and 24 year-old Marlon Brando is more focused on where he’s going to get his next meal than how he’s going to find his next role. And here I thought “Starving Artist” was just a little phrase actors liked to joke about. Apparently there REALLY ARE starving artists. Like they’re desperate for food. Such was Brando’s life at the time, where he was seen as a young talented actor, but also misguided, a bit of a mumbler, and a little strange.

In another part of New York City, director Elia Kazan is trying to put together a cast for Tennessee Williams’ amazing play, “A Streetcar Named Desire.” It’s a tricky proposition because his boss, the witch-like Irene Selznick (divorced wife of David O. Selznick) doesn’t want Kazan to direct. The only reason he’s on is because Tennessee likes him. But Irene is only allowing the two to have so much fun. She’s got one major rule for this production: Kazan has to cast a star in the role of Stanley. If that doesn’t happen, he’s getting fired.

The thing is, Kazan doesn’t like any of the stars Irene’s throwing his way. Burt Lancaster sure is a heartthrob and fits the look, but the part of Stanley is way more than looks. We have a man who rapes the female lead. There has to be a darkness to him, troubled eyes that make you believe in a moment like this. And Kazan is having a hard time finding that quality.

That is until he hears about Brando, for all intents and purposes a bit of a doof, but a doof that runs through women faster than a German Blitzkrieg. And yet no matter how many of these women he fucks over, they all want to come back to him. They all want more. THAT’S the quality Kazan needs, so he comes to Brando’s home and asks if he’ll give him an audition.

Kazan falls for Brando immediately but knows that if he’s going to slip him past Irene, he’s going to need Tennessee’s blessing. Tennessee is a piece of work himself. Famously gay, he had Brando come over and do the rape scene, with HIMSELF playing the role of Blanche (the rape victim). The scene turns out so hot that Tennessee is all in for Brando. But now comes the real test – seeing if the snobby Braodway crowd will accept this unknown in such a big part. Brando will have to channel the man he equally loves and detests the most, his heartless father, to play the role in a way that will make it work, a tightrope that may be too thin to navigate when it’s all said and done.

“Hey Stella” was a fairly decent screenplay. What I liked most about it was its portrayal of Brando. Everyone knows this guy had some serious issues, and by exploring his relationships with his mom, father, girlfriend, lover, best friend, and acting teacher, we get to see how all those issues came about. You feel like the weight of the world is on his shoulders whenever he wakes up in the morning. There’s a happiness you’re desperate for Brando to achieve, even though deep down you know it’s impossible. That this is a broken man who cannot be fixed. It’s the reason why he was such an amazing actor, but also why he was so terrible at life.

This reminded me that a great way to explore the depth of a character is to see him through multiple relationships. Each one peels back a layer that we couldn’t have seen through any of the other relationships. His relationship with his father taught us how important it was for him to please this man. His relationship with his mother taught us how much he wanted to be loved. His relationship with Ellen, his girlfriend, taught us how destructive he could be towards others. His relationship with his best friend and roommate, Wally, taught us how loving he could be. His relationship with Stella, his acting coach, taught us how dedicated he was to the craft of acting.

I so often tell young writers that their stories and their characters lack depth. Well, using relationships to explore different sides of your character is one way to fix that.

Much like “42,” “Hey Stella” doesn’t just focus on Brando’s coming out party, it also leads us into Kazan’s, the director’s. Kazan has the perfect wife, and yet he constantly cheats on her with his mistress. His battles with Irene and desire to get the right actor to play Stanley are all fairly interesting. But truth be told, his life wasn’t nearly as compelling as Brando’s, and therefore whenever I was with him, I wanted to get back to Brando.

The script moves along at a nice clip, with the goal of Brando trying to get the part of Stanley keeping us invested. But instead of the drama of getting that part ramping up in the final act, it seemed to dissolve. Instead of Irene slamming her fists down and demanding she get her way with the star actor, she just sort of accepts Brando and fades into the background. This wasn’t true to her character and it made for a lazy ending that ran out of steam. We needed the stakes and the conflict at their highest in the third act, for Irene to be more present and dominant as she tried to stop the play. Instead we get the opposite.

In the end, this was a neat little script with some nice info on how Brando got the part in “A Streetcar Named Desire.” But outside of Brando’s character, everything and everyone was a little too soft, a little too blasé, a little too light on the drama. The script suffered the consequences of this issue most in its final act, when the story faded away harmlessly. I think “Hey Stella” is worth reading because of the Brando element. I just wish the story had a little more kick to it.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: We all know I’m not a huge fan of biopics. Or I should say, I’m not a huge fan of the way most biopics are written. I think they’d be better off if the writers approached them as a story instead of a documentary, which “Hey Stella” did a fairly decent job of. Regardless of all that, this reminded me that you should write in the genre that you want to spend the rest of your career writing. The specs themselves may not sell, as was the case here, but it got Shepherd paid work on his genre of choice, the biopic, since he’d proven himself in the genre already. I still think you should always give yourself the best opportunity possible by making your script as marketable as it can be, but in the end, you should be writing in the genre you feel the most passionate about.

Netflix throws their hat in the ring for original programming. But is this Spacey and Fincher f*cking around with a desperate new company’s money? Or is this show actually good?

Genre: Political Drama (TV)

Premise: (from IMDB) Francis Underwood is Majority Whip. He has his hands on every secret in politics – and is willing to betray them all to become President.

About: David Fincher went looking for a writer for this project 3 years ago. He came upon “Ides of March” scribe Beau Willimon, who excited him with his desire to cherry-pick the best parts of the original UK show then reinvent everything else for the American audience. This is Netflix’s first original show, a show that bucked the traditional TV release model and released all 13 episodes at once.

Creator: Beau Willimon

Writer of pilot: Beau Willimon (based on the 1990 TV series by Andrew Davies and Michael Dobbs)

Details: 60 minutes long

Kevin Spacey. David Fincher. How bad can it be? As bad as the writer allows it to be. So who wrote it? Beau Willimon. Wait a minute? Beau WHO?? Chances are, you don’t know that name. Well, I can tell you he wrote a hell of a screenplay (Farragut North – which ended up becoming “The Ides Of March”) that made the Black List in 2007 and which I reviewed a couple of years ago. Outside of that, I don’t think Beau’s done much. In that sense, he’s really lucky that Ides got made (for five years it was deader than Hugo Chavez) because if it didn’t, he would’ve never got an opportunity like this, which appears to be the opportunity of a lifetime.

You get to write a show that has the biggest budget on television (over 4 million bucks an episode) for a new network that’s spending outrageous money solely to make a splash in an industry that’s kicking every other industry’s ass. Yup. That’s why I’m reviewing a TV pilot today (and plan to review more). Everyone wants to get into TV. All my writer friends are ditching the pie in the sky spec sale scenario and moving into television. Like it or not – this is where all the writing heat is these days.

And what better way to celebrate that than by checking out the pilot for House of Cards, a project that probably would’ve never been made if it wasn’t for Netflix. The show is different. It’s risky. And it takes on subject matter that’s typically ignored unless your name’s Aaron Sorkin (people don’t like to see their politics dramatized. They prefer the real-life stuff. Case in point – check out how Ides of March did, despite great writing and a high profile cast).

If you’re like me, you might’ve been worried about a couple of other things, as well. First, that this was a Kevin Spacey vanity project. We all know how those turn out (Beyond The Sea). Fincher directing alleviated some of that, but I was also worried about this being something every other network passed on but Netflix was so desperate to work with some top names that they let Spacey and Fincher come in with their garbage and use them to make a weird show nobody wanted to see. “Ha ha” they’d say, as they stole 50 million dollars from this clueless video rental company.

Anyway, House of Cards follows Francis Underwood, a congressman who’s been cleaning up messes for his party for 30 years. He’s paid his dues. He’s done his time. And now he’s backed the perfect candidate, who’s gone ahead and become president. His reward for all this? Secretary of State, a position he’ll surely get as he’s responsible for everyone on the president’s team (including the president himself) having a job.

But things don’t go as planned. When Francis takes his first meeting with the president to start game-planning, he’s met instead with the prez’s right-hand woman, Linda Vasquez. Vasquez has some bad news for Francis. They’ve decided against making him Secretary of State. They need him, instead, to stay in Congress. Francis. Is. PISSED. But he holds it together. He plays the roll of the good son. He nods, says he’ll do his best, and Vasquez is thrilled. She knew that would be a toughy.

Well Vasquez shouldn’t be too thrilled. Francis doesn’t spend 30 years of careful maneuvering to get to this point only to have his dream position snatched away and NOT DO ANYTHING ABOUT IT. NO no no. Francis decides to become the nastiest dirtiest politician in Washington. Now we don’t quite know what this means yet, but when he blackmails a senator and starts dishing dirt to a hot new Washington Post blogger, we get an idea. This guy wants to either puppeteer the presidential office or destroy it entirely.

Okay, there are a lot of factors in play here for this analysis. First off, I’m dissecting a pilot as opposed to a film. I don’t know as much about TV, so that’s going to be a challenge. On top of this, we’re breaking down a show that got carte blanche from Neflix to do whatever the hell it wanted. According to Beau, Netflix never gave a single note. What that likely resulted in was a lot of experimenting, a lot of rule-breaking. It’s always fascinating to watch people break rules because there’s an inherent part of us that believes rules are bullshit. That if we stopped being a slave to them, we’d actually write something original and exciting and different and great (for once). Of course, there’s also the analyst side of me who’s endured the 3000 scripts that you guys never see, the ones where writers are always trying to break the rules. And every single one of them is a disaster.

Fincher and Willimon don’t disappoint. They break two major rules within the first few minutes. Are you ready for this? The show opens with our main character KILLING A DOG. There’s an old joke in Hollywood that you never have your main character kill an animal because the audience will hate him. As almost a way to say “FUCK YOU” to convention, Willimon and Fincher literally start their show with Francis killing a dog. Wow.

The second thing? They have Francis break the fourth wall. Yes, he talks directly to the audience. Talking directly to the audience is almost always a disastrous move. It’s just really hard to get right. For every Ferris Bueller, there are a thousand….well, movies you’ve forgotten because they had a character talking to the audience. And then of course, I’ve never seen this device used in a DRAMA before. When a character like this is funny, talking to us doesn’t seem so strange. We’re laughing! But to use this device in a DRAMA?? Wow, that’s chance-taking right there.

My first reaction to this? NOOOOOOOOO. Gag me with a moldy plastic spoon. But here’s the funny thing. This second rule-breaking stunt actually fixed the first one. Who doesn’t hate a character after they’ve killed a dog? Raise your hand. But when Francis starts talking to us, we feel connected to him. That’s the one big advantage with breaking the fourth wall. You create a direct connection between the audience and the character that you can’t get through any other device. So we start to feel like this guy’s friend, like his accomplice, and for that reason, we kind of forgive him for killing that doggy, just like we’d forgive one of our own friends for doing something terrible.

Another reason why we’re able to overlook the pooch-killing? Ironically, the answer lies within the canine family. Because Fincher and Willimon turn Francis into the world’s biggest underdog. This guy helped a nobody become the president of the United States. And then that president fucks him over and doesn’t reward him, basically relegating him to cleaning the shit out of the company toilets? How can we not root for Francis after that?

This leads me to one of the cooler devices Willimon used throughout the script, which is that he’d set up the stakes for many of his scenes ahead of time, giving later scenes added pop. For example, Francis spends the first 10 minutes of the episode basically telling us how hard he’s worked to get to this point. We can see the relief in his eyes, the thankfulness that after 30 years, everything’s finally going to pay off. In other words, we’ve established his STAKES. Getting here is everything to him.

This is why the later scene where Vasquez tells him they’re going with someone else is so powerful – BECAUSE WE KNOW HOW MUCH THIS MEANS TO HIM. We set up those stakes earlier so that the audience would be devastated when he received the heartbreaking news. Had Willimon not dedicated those first few scenes to setting up Francis’ excitement for becoming Secretary of State, the rejection scene would have been 1/10 as powerful. We see this device being utilized several times during the episode to great effect.

I also found it interesting how much this felt like a feature. There were none of those gimmicky cliffhangers you’d typically find right before the commercial breaks in a “normal” TV show. Everything unraveled slowly and meticulously. It was like they weren’t afraid not to grab you. And it worked, mainly because of those differences (the breaking of the 4th wall) and the strong characters. If that’s one thing I’ve learned, it’s that TV has to have strong characters. Because even the lesser guys are going to be on dozens of episodes. So you have to make them all compelling. That can’t be easy.

I feel like I could keep talking about this medium forever because there’s so much about it I don’t know yet. Instead, I’ll just say to check out House of Cards on Netflix if you get a chance. It’s definitely worth it.

[ ] what the hell did I just see?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[xx] worth watching

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: To create sympathy for your main character, have someone screw him over. But if you want to add an extra dose of sympathy, have them screw him over AFTER he’s done something nice for them. This is why we sympathize with Francis so much even though he’s a manipulative dog killer.

How to screw up a Hollywood film and an indie film all in one weekend.

Genre: Fantasy/Adventure

Premise: (from IMDB) The ancient war between humans and a race of giants is reignited when Jack, a young farmhand fighting for a kingdom and the love of a princess, opens a gateway between the two worlds.

About Giant Slayer: This film was directed by Bryan Singer, trying to get out of director jail after Superman Returns and Valkyrie. It was written by an interesting trio. Christopher MacQuarrie, who of course has been a big part of Singer’s career since The Usual Suspects. Dan Studney, a TV writer (he wrote the TV series version of Weird Science) who’s big feature credit is “Reefer Madness,” the musical. And finally Darren Lemke, who wrote Shrek: Forever After, which I believe is the fourth film in the series, though I called Dreamworks for confirmation on this and even they weren’t sure. While I can’t give you a timeline of every writer’s participation, my guess is that Lemke wrote the initial draft, Studney wrote another draft, and then when Singer was brought on as director, he used his go-to writer, McQuarrie, to get the script where he wanted it. The film came out this weekend and grossed an underwhelming 26 million dollars, a disastrous take for a product that cost 200 million to make.

About Stoker: Stoker was a hot script from 2011 that got everyone in town riled up. Imagine their surprise when it was revealed to be written by Wentworth Miller, the doofy lead actor in the 3 seasons too long Fox thriller, “Prison Break.” He’d written the script under a pseudonym so as not to be discriminated against (Oh, another actor who thinks he can write, eh!). It paid off as the script sold for mid six-figures. And if that wasn’t enough, legendary Korean director Chan-wook Park decided to make Stoker his first American film! Park is responsible for such classics as, “Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance” and “Oldboy.” The film stars Matthew Goode (Watchmen), Mia Wasikowska (Alice In Wonderland) and Nicole Kidman (Celebrities Addicted To Plastic Surgery).

Writers (Giant): Darren Lemke, Dan Studney and Christopher McQuarrie.

Details (Giant): 114 minutes long

What do you get when you couple Jack The Giant Slayer with Stoker?

A lot of disappointment.

However, that disappointment may not be distributed in the way you’d think it would be. We have some high quality craftsman working on both projects here (Singer and McQuarrie on one, Park on the other), yet you’d assume that the bedroom swallowing sinkhole would reside with the picture celebrating CGI giants. Not so fast. Stoker was easily the worst film I’ve seen all year. And “Giant Slayer” was kinda okay (even if Miss Scriptshadow called it “a flat piece of trash” – hey, what do girls know about giants, right?).

“Giant Slayer” follows our plucky peasant hero, Jack, sticking up for a young bullied woman (who turns out to be – SURPRISE! – the princess). He then gets swindled into trading some beans for his horse at the market, and comes home to get yelled at by some angry old dude with really bad teeth (his great uncle maybe?).

Later that night, the princess comes by to thank him, and one of those beans falls through the floor, landing in dirt. A storm follows and the roid bean sprouts. Like REALLY sprouts. The resulting gigantor plant shoots up into the air, taking the house, AND THE PRINCESS, with it! The king shows up the next day, wanting Jack to tell him where his daughter is, seemingly blind to the fact that there’s a thousand-feet in diameter bean-stalk behind them. Jack tells him the princess is up there with it, so the king sends his best climbers, and Jack, to go get her.

They make it to the top, where they discover a secret land in the sky that is home to giants. Not only do the giants capture our pint-sized crew, but learn that the bean stalk they came on heads down to Human-Land. Since everyone knows giants love the taste of humans, they decide to head down there to satiate a serious case of the human-munchies. The only problem is that Jack is one crafty little individual. And once he falls in love with the princess, he’ll do anything to save her, even if that means taking down giants, mother*&%er.

It’s funny. Last Thursday I was going to do an article about “writing the blockbuster.” Blockbusters are unique beasts. You approach them slightly differently from “traditional” scripts. Set-pieces become a huge part of your approach, so that was going to be a big part of the article.

But sadly, this blockbuster made the same mistake at script level as pretty much every other blockbuster I read. The setup is the best part. And then it falls off a cliff (no pun intended) becoming a mediocre, occasionally amusing piece of fluff. I’m not going to lie, I was excited to get to the giants. From what I’d seen in the previews, they looked amazing. That anticipation made the first act suspenseful, even if it amounted to your basic setup scenario of peasant-can’t-be-with-princess-cause-he’s-a-peasant.

However, once we get to Giant-Land, it becomes Boring Central. Remember, since the second act no longer has the advantage of anticipation (you’ve basically shown your cards, a.k.a. the Giants), the reader/audience must love the characters in order to stay interested. None of the characters here were lame. But none of them stood out either. If I was giving grades, almost every one of them would’ve received a “C.” They were all average.

This is a deadly combination when writing a screenplay. It’s the equivalent of a pilot losing access to his hydraulics as he comes in for a landing. A second act has WAY MORE slow moments than a first act does. So for those moments to be entertaining, you need interesting characters engaging in strong conflict. We had the conflict part (there was a bad guy wreaking havoc within the human team. Jack couldn’t have the princess because of the class difference) but BECAUSE THE CHARACTERS WERE SO AVERAGE we just didn’t care.

What nearly saved this movie was the ending. It was high caliber action set-pieces at their best. When the giants come down to our world and start hurling trees and windmills at our puny little counterparts, I was in awe. The giants looked great and the battle was inspired. The problem was, as I already mentioned, there was no one worth rooting for. Nobody stood out. Even the always good Stanley Tucci plays a boring villain. This simply isn’t worth your time unless you have a 12 year old son. Oh well.

BUT!

But. If someone’s put a gun to your head and told you you HAD to either watch Stoker or Giant Slayer, for the love of all that is holy, go see Giant Slayer. Stoker is abysmal. It’s terrible. It’s got an interesting backstory, a great director, but it’s just terrible. It’s the very definition of style over substance, which is what you’d assume I’d say about Giant Slayer. But here we obviously have a director who’s more interested in visual tricks and award-winning cinematography than, well, AN ACTUAL STORY!

That’s assuming there was a story. I haven’t read the script. I know Roger reviewed it a long time ago, but I skipped the synopsis due to spoilers. I mean, nobody in this movie utters a line that someone would say in real life. Everyone acts like they know they’re in a movie and therefore must say something poignant or eerie. That is when they DO talk. Because 95% of this movie is dedicated to Matthew Goode staring at people! I swear to you. That’s almost the entire movie. Someone says something, then cut to Matthew Goode staring at them in a really eeire way for 5 minutes.

What’s it about? The short answer is nothing. The long answer is… Disturbingly reclusive India has just lost her father, who’s mysteriously died in a car accident. So his brother, an uncle India never knew she had, shows up to offer the family support. He takes a particular interest in India, whom he tells, “I just want to be your friend.” Except there’s nothing friendly about his rape-stares, which would make even a Catholic priest uncomfortable.

People close to the family, like the grandma and an aunt, start dying mysteriously, and eventually India learns that her dear uncle is a crazy serial killer. Except India isn’t put off by this. She’s turned on by it! Like SERIOUSLY turned on. And she wants in. Complicating matters is her alcoholic mother, who makes daily shameless advances at her dead husband’s brother. When India sees this, she gets jealous, and we get a mother-daughter cat fight. Rreow!

KILL ME IF I EVER HAVE TO SEE THIS MOVIE AGAIN.

It was so bad. There was no plot, nothing driving the story forward besides the mystery uncle, which got boring after 10 minutes. That didn’t stop Miller and Park from stretching that mystery out for another 40 minutes though. But the real problem here was that nothing felt connected. Each scene felt like Park experimenting (a 5 minute trip down to the basement for ice cream becomes a celebration of dancing lights), and once he was done, he’d go on to the next experiment, regardless of whether those two scenes fit together. There’s a moment around the midpoint, for example, where India is at school. Since when did India attend school??? Nothing from the first 50 minutes indicated that India was in school at the time. That was a microcosm of the entire movie. No progression of story. No point to the story. Random shit popping up out of nowhere. Weird scenes completely dependent on mood and lighting.

Stoker is a mess of the highest order. At best it’s a master filmmaker making his dream student film. At worst it’s a distracted director trying to make sense of a pointless script. I would strongly recommend avoiding this film. It’s awful.

JACK THE GIANT SLAYER

[ ] what the hell did I just watch?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the price of admission

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

STOKER

[x] what the hell did I just watch?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the price of admission

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: (from “Giant Slayer”) Remember this. DO SOMETHING UNIQUE WITH YOUR CHARACTERS. Make them stand out in some way. Give them something we haven’t seen before in from movie characters. Or else they will be generic. And no matter how awesome your plot is, we won’t care because your characters are boring. Anticipation and story build-up might help us ignore this during the first act, but once the second act comes around – the act that depends on your characters – your story will die a quick death.

What I learned 2: (from “Stoker”). Make sure there’s a well-thought-out and compelling plot to your story. Your characters might be interesting as hell. But if we don’t know what the hell’s going on half the time or understand what their goals or motivations are, we’ll quickly get bored and check out on you.

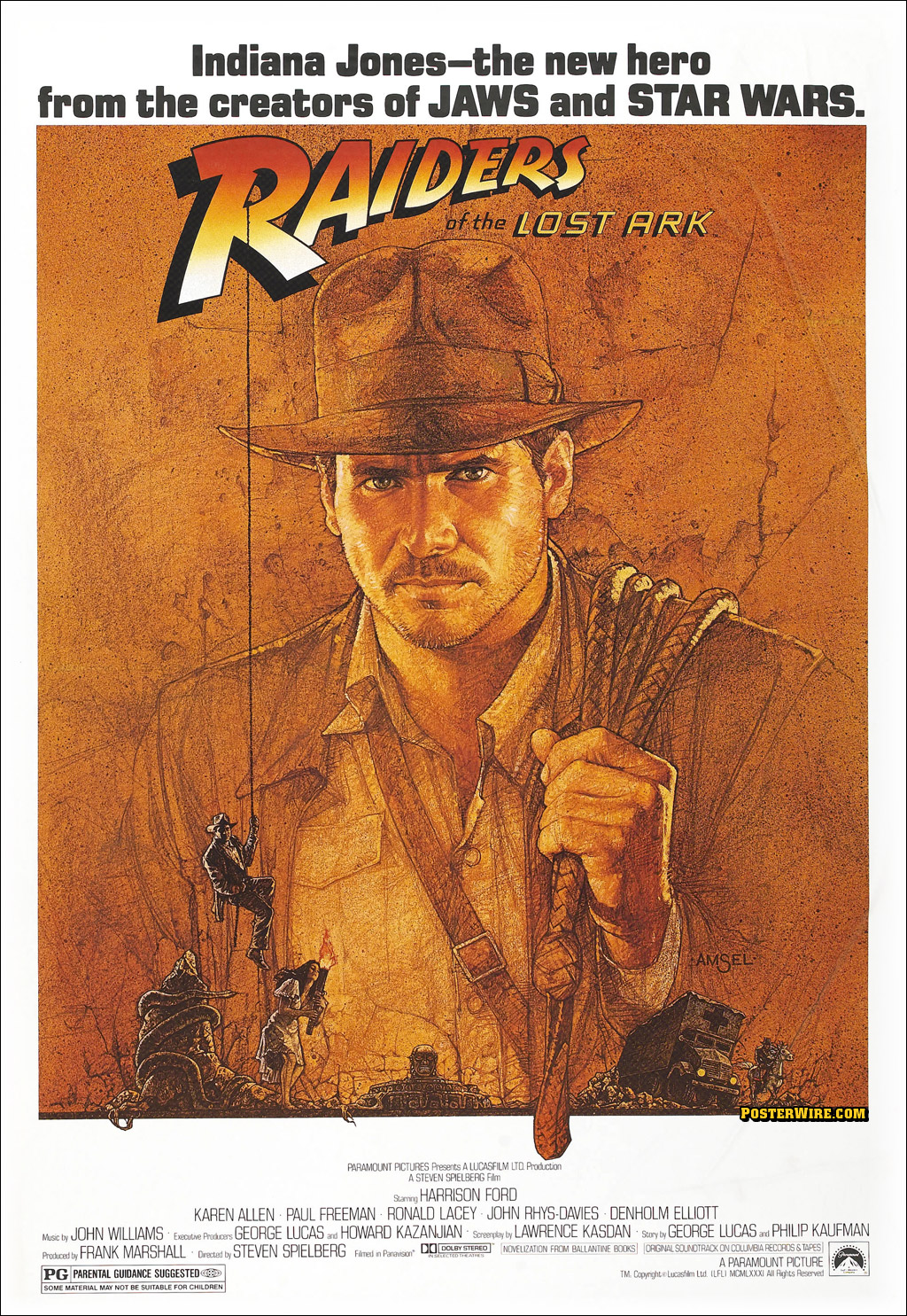

What’s the easiest way to tell the difference between an amateur and a pro script? That’s easy: CHARACTER DEVELOPMENT. The pros know how to do it. Amateurs don’t. Most amateurs don’t even attempt to add character development. And the ones who do usually use something like addiction or the death of a loved one to add depth. It’s not that you can’t or shouldn’t add these traits. But if you really want to delve into your character and make him/her three-dimensional, you want to give them a flaw, then have them battle that flaw during their journey, only to overcome it in the end. This is called a “transformation,” or an “arc.” It’s when your character starts in a negative place and finishes in a positive place. If you really want to boil it down and get rid of the fancy-schmancy screenwriting terms, it’s called “change.” And the best movies have central characters who go through a big change.

Now I don’t have 50 hours to write about character development so I can’t get too detailed here. But I should tell you a few things before I get to the meat of the article. Character flaws are more prominent in some genres than others. For example, you should ALWAYS include a character flaw in a comedy. Our inability to overcome our flaws is essentially what leads to all the laughs in the genre. Action movies, on the other hand, often have heroes who don’t change. The story moves too fast to explore the characters in a meaningful way. Thrillers are similar in that respect, although a good thriller will find a way to squeeze in a character flaw (I remember that movie “Phone Booth” with Colin Farrel and how it dealt with a selfish character). With horror, it depends on what kind of horror you’re writing. If you’re writing a slasher flick, character flaws aren’t necessary. A thinking-person’s horror film, though? Yeah, you want a flaw (the lead’s flaw in The Orphange was that she coudln’t move on with her life – she was obsessed with the past). In dramas, you definitely want flaws. Westerns as well. Period pieces, usually.

In my own PERSONAL opinion, you can and should ALWAYS give your characters flaws, no matter what the genre. People are just more interesting when they’re battling something internally. Without a flaw, without something holding them back, characters don’t have to struggle to achieve their goal. And that’s boring! Think about it. I always tell you to place obstacles in front of your hero so that it’s difficult for them to achieve their goal. Well what if while your character’s battling all these EXTERNAL obstacles, he also has to battle a huge INTERNAL obstacle?? Much more interesting, right??

You just need to match the kind of flaw and level of intensity of that flaw to the kind of story you’re telling. For example, Raiders is a fun action flick, so we don’t need a big deep flaw for Indy. Hence, Indy’s flaw is his lack of belief in religion and the supernatural. He doesn’t care about the Ark’s supposed “powers,” because he doesn’t believe it has any. But in the end, he finally believes in a higher being, closing his eyes so the spirits from the Ark don’t kill him. It’s a very thin and weak execution of Indy’s flaw, but the story itself is fun and light so it does the job.

The problem I always ran into as a writer was that nobody gave me a toolbox of flaws that I could use. That’s why I wrote today’s article. I wanted to give you eleven (the new “ten”) of the most common character flaws that have worked over time in movies. Now when you read these, you’ll probably say, “Uhh, but that’s too simple.” Yeah, the most popular flaws are simple. And the reason they’re simple is because they’re universal. That’s why audiences find them so moving – they can relate to them. Remember that – the more universal the flaw, the more people you’ll have who can identify with that flaw.

1) FLAW: Puts work in front of family and friends – This is a flaw that tons of people relate to, especially here in the U.S. where our country is set up to make us feel like losers unless we work 60 hours a week. Balancing your personal and professional life is always a challenge. It’s something I personally deal with all the time. I work a ton on this site. And when I’m not working on the site, I’m working on future ideas for the site. That leaves me with very little time to go out and have fun. The question then becomes, over the course of the story, “Will the hero realize that friends and family are more important than work?” We see this explored in movies time and time again. Most recently we saw it in Zero Dark Thirty (in which Maya never overcomes her flaw). Or last year with Billy Beane (Brad Pitt) in Moneyball. Again, it has to match the story you’re telling, but it’s always an interesting flaw to explore.

2) FLAW: Won’t let others in – This is a common flaw that plagues millions of people. They’re scared to let others in. Maybe they’ve been hurt by a past lover. Maybe they’ve lost someone close to them. Maybe they’ve been abandoned. So they’ve closed up shop and put up a wall. The quintessential character who exhibits this trait is Will in Good Will Hunting. Will keeps the world at arm’s length, not letting Skylar in, not letting Sean (his shrink) in, not letting his professor in. The whole movie is about him learning to let down his walls and overcome that fear. We see this in Drive, too, with Ryan Gosling’s character refusing to get close to anyone until he meets this girl. We also see it with George Clooney’s character in Up In The Air.

3) FLAW: Doesn’t believe in one’s self – This should be an identifiable flaw for anyone in the entertainment industry. This business is full of doubters, especially when you’re still looking for a way in. It’s tough to muster up the confidence in one’s self to keep going and keep fighting every day. But this doubt isn’t limited to the entertainment industry. Billions of people lack confidence in themselves. So it’s a very identifiable trait and one of the reasons a main character overcoming it can illicit such a strong emotional reaction from the audience. It makes us think we can finally believe in ourselves and break through as well! We see this in such varied characters as Rocky Balboa, Luke Skywalker, Neo, and King George VI (The King’s Speech).

4) FLAW: Doesn’t stand up for one’s self – This flaw is typically found in comedy scripts and one of the easier flaws to execute. You just put your character in a lot of situations where they could stand up for themselves but don’t. And then in the end, you write a scene where they finally stand up for themselves. The simplicity of the flaw is also what makes it best for comedy, since it’s considered thin for the more serious genres. I also find for the same reason that the flaw works best with secondary characters. We see it with Ed Helms’ character in The Hangover. Cameron in Ferris Bueller’s Day Off (afraid to stand up to his father). And George McFly (Marty’s dad) in Back To The Future.

5) FLAW: Too selfish – This flaw I’m sure goes back to the very first time two homo sapiens met. There’s always been someone who puts themselves in front of others. Everybody in the world has someone like this in their life, so it’s extremely relatable and therefore a fun flaw to explore. It does come with a warning label though. Selfish characters are harder to make likable. Just by their nature, they’re not people you want to pal up with. So you need to look for clever ways to make them endearing for the audience. Jim Carrey in Liar Liar for instance – an extremely selfish character – would do anything for his son. Seeing how much he loves him makes us realize that, deep down, he’s a good guy. But it’s still a tough flaw to pull off. I can’t count the number of scripts readers or producers or agents have rejected because the main character “isn’t likable,” and usually it was because of a selfish asshole main character. A few more notable selfish characters were Han Solo in Star Wars, Bill Murray’s character in Groundhog Day, and Mark Zuckerberg in The Social Network.

6) FLAW: Won’t grow up – This is another comedy-centric flaw that tends to work well in the genre due to the fact that men who refuse to grow up are funny. We see it in Knocked Up. We see it in The 40 Year Old Virgin. We saw it with Jason Bateman’s character in Juno. We even see it on the female side with Lena Dunham’s character in the HBO show, Girls. I’ll admit that this flaw hit a saturation point a couple of years ago, so either you want to find a new spin on it (like Lena did – using a female character) or wait a year or two until it becomes fresh again. But it’s been proven to work because of how relatable a flaw it is. Who isn’t afraid to grow up? Who isn’t afraid of all the responsibilities of being an adult? That’s what I want to get across to you guys. These flaws all work because they’re universal. Everybody has experienced them in some capacity.

7) FLAW: Too uptight, too careful, too anal – You tend to see this flaw in television a lot. There’s always that one character who’s too anal, the kind of person you want to scream at and say, “LET LOOSE FOR ONCE!” We all have friends like this as well, so it’s another extremely relatable flaw. Joel Barish (Jim Carrey) in Eternal Sunshine Of The Spotless Mind is plagued with this flaw. Jennifer Garner’s uptight hopeful mother in Juno is driven by this flaw. And you’ll see this flaw in Romantic Comedies a lot, in order to give contrast to the fun outgoing girl our main character usually meets (Pretty Woman).

8) FLAW: Too Reckless – You’ll usually find this flaw in more testosterone-centered flicks. Like with Jeremy Renner’s character in The Hurt Locker, Martin Riggs (Mel Gibson) in Lethal Weapon, or James T. Kirk in the latest incarnation of Star Trek. The flaw dictates the character enter a lot of big chaotic situations in order to battle his flaw, so it makes sense. I’m not a huge fan of this flaw, though, because I believe the best flaws are universal. That’s why they emotionally manipulate audiences, because people in the audience have experienced those flaws themselves. Recklessness isn’t something people emotionally respond too. That’s not to say it isn’t effective and doesn’t allow for a satisfactory change in an action flick. It just doesn’t hit that emotional note for me like a lot of these other flaws do.

9) FLAW: Lost faith – This is a bit of cheat because questioning or losing one’s faith isn’t necessarily a flaw. But it’s an incredibly relatable experience. Something like 97% of the people on this planet believe in a higher being. But a majority of those people question their faith because now and then something terrible happens to shake it. Which is why you’ll see a ton of characters enduring this “flaw.” We saw it with Father Damian Karras in The Exorcist after his mother dies. We see it with Mel Gibson’s character in Signs after his wife is killed in a car accident. Again, losing someone close to us is a universal experience, so it’s one of those “flaws” that works like a charm when executed well.

10) FLAW: Pessimism/cynicism – This flaw isn’t used as much as the others, but you’ve seen it in movies like Sideways with Miles (Paul Giammati has actually made a living out of this flaw), Terrance Mann ( James Earl Jones) in Field of Dreams, and Edward Norton’s character in Fight Club. I always get nervous around flaws that make characters unlikable and pessimism tends to do that for me. For example, I never warmed to Sideways as much as others because Miles’ pessimism was so grating. But on the flip side, tons of people relate to that character for the very same reason. They’re just as frustrated with life as he is. Which is why the movie has its fans.

11) FLAW: Can’t move on – This is one of the lesser-known flaws but a powerful one. It’s basically about people who can’t move on, who are stuck on someone or something from the past. Their obsession with that past has stilted their growth, and brought their life to a screeching halt. Most famously, you saw this in Up, with Carl Fredricksen, who hasn’t been able to get past his wife’s death. But you may also remember it from the movie Swingers, where Mike (Jon Favreau) is still obsessed with the girl who dumped him. He keeps waiting for that call. With relationships being so fickle, people are experiencing this flaw ALL THE TIME, so it’s very relatable and therefore very powerful when done right.

So there you have it. You’ve now got eleven flaws to start applying to your characters. And remember, those aren’t the only flaws you can use. They’re just the most popular. As long as you start your character in a negative place and explore how they get to a positive place, you’re creating a character with an arc, a transformation. There’s more to character development than this, which I discuss in my book, but getting the character flaw down is probably the most important step. Feel free to offer some of your own character flaw suggestion in the comments section. I’ll be watching closely so I can steal the best ones. :)

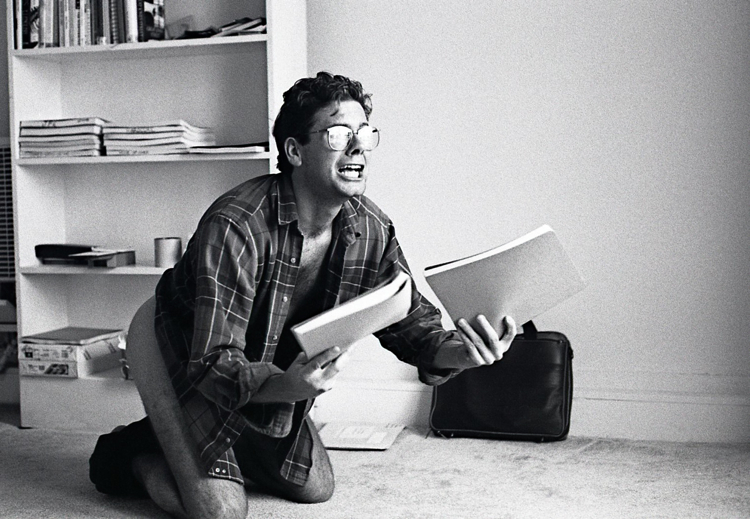

My favorite writer is back! John Jarrell. You may remember him from the awesome interview I did with him a few months ago. The guy has a ton of screenwriting knowledge and unlike us hack bloggers, the man’s actually been in the thick of it for 20 years, fighting the good screenwriting fight, landing those six figure jobs we all dream of. Which is why I’m more than happy to promote his new screenwriting class – Tweak Class — starting this January. Who better to learn from than the guy who’s seen it all? Goddamit, he’s even taken his pants off for a publicity shot (that’s really him above!). This man is dedicated. And today, he’s going to share with us a couple screenwriting stories from Hollywood Hell. I enjoyed this piece so much I told John he needs to write a whole book of this stuff. Let him know if you feel the same in the comments!

“Will You Please Buy My Script Now, Please?” — One Writer’s Journey Into the Troubling Bowels of Development.

By John Jarrell

Back in 1995, I wrote a Horror spec called The Willies. It was essentially Carrie with Evil Twins. People are constantly abusing and shitting on these orphans, until at last, after making a pact with the devil, they take their bloody revenge.

My agent went out with it and immediately got a sadistically low-ball pre-emptive bid from a smaller studio in town. By that point in my life, my dream of becoming a legitimate screenwriter was nearing extinction. I’d been struggling in L.A. for four years, was stone-cold broke, about to lose my apartment, and my girlfriend and I were subsisting solely on the 49-cent value menu at Taco Bell. Facing even more of that ugliness, I did what struggling young writers have to do sometimes — I sucked it up and took the shit money, simply glad to survive and hopeful I would live to fight another day.

First day working, I go into a story meeting with the company’s “Creative” VP and Head of Development. We dug in and spent several hours doing notes starting Page One — discussing what they thought worked, what didn’t, and what I’d need to address in my rewrite.

At one point, the VP looks up at me and says, “Wow, John. This description on page fifty-two is really good writing. Would you mind reading it out loud?”

Flattery will get you everywhere with a screenwriter, and I’m sure I flushed with pride as I found the page and paused to clear my throat.

The set up was simple — a grieving daughter (our protagonist) looking through her deceased Mother’s belongings, which have been boxed up and stored in the attic. The beat offered a brief respite from all the genre action, gave us a further glimpse into our lead’s character, and prompted her discovery of an important clue at the end.

This was the description I wrote, verbatim —

“She rifles several of the boxes, finding little more than old letters and checkbook stubs, key chains and their forgotten keys. The meaningless remnants of our too brief lives.”

There was a long pause after I finished. The VP and Head of Development were nodding their heads in synchronized approval. Then the VP says —

“Yeah, it’s really great. Great stuff.”

(HARD BEAT)

“Lose the poetry, John, cut it all out. It’s slowing down the script.”

I’d never been quite so close to crapping my pants. Did he just say LOSE… THE… POETRY? a.k.a. LOSE THE GOOD WRITING? Wantonly kill off two short sentences — two sentences he actually likes — which perfectly sell the moment? And replace them with what, Mr. Hemingway? “She opens her dead mom’s shit and finds a mysterious clue!”

Like every other indignant scribe in Hollywood history, I sat hooded in a queasy half-smile, cerebral cortex locking up. Surely “development” couldn’t be like this everywhere? Surely this exec must be a nutter, a lone gunman of sorts, some soulless script assassin who didn’t value lightweight artistry over the groan-inducing stock lines which had been stupefying readers for decades?

But I was wrong. He wasn’t the slightest bit insane. In fact, Mr. Company VP was the Gold Standard — an Industry veteran and Number Two guy at the whole company! And if I didn’t “lose the poetry” voluntarily, believe me, he would have no qualms hiring another low-ball writer to lose it for me.

Way back at NYU, an older studio vet had once shared a bit of sage wisdom with me — “It’s better for you to fuck up your script the way they want then have ’em hire somebody else to fuck it up for you.”

As baffling and counterintuitive as his advice had seemed, now I grabbed onto it like a life vest. I labored at “losing the poetry”, beat after tight beat, good scene after good scene. For nine agonizing months, they “developed” the script this way. Any nugget of goodness was ruthlessly ferreted out, any clever turn of phrase or interesting character tick was quickly sandblasted into beige. My reward, such as it was, was being kept onboard on as sole writer.

Finally, they were ready to go out with it. And they did. And in a matter of three short weeks, the company blew a sure-thing co-financing deal, flatlined similar offers via absurd distribution demands, then shelved the project out of self-loathing and/or shame, never to see daylight again. Their epic fail also left The Big Question still looming — Had sacrificing all my poetry to the Commercial Film Gods made my script better… or worse? Now, tragically, there was no way I’d know for sure.

Instead of my project — and I’m totally NOT kidding here — the company produced the urban side-splitter “Don’t Be A Menace to South Central While Drinking Your Juice in the Hood” in its place. It survived three demoralizing weekends before being euthanized and laid to rest in the VHS market.

During what I thought a poignant last ditch appeal, before all the lights had been turned out, I’d made the case to the company that horror was an American genre mainstay, essentially a license to print money when well-executed. This is what that same VP told me —

“Horror’s dead, John. Nobody wants horror anymore. It’s all about the urban audience.”

Scream opened that same December and made $173,046,663 worldwide. In its wake, an uninterrupted avalanche of extremely profitable low-budget horror pics overran the coming decade.

And me? Exactly one year after the sale, my girlfriend and I found ourselves back at Taco Bell.

* * * * *

Those first professional cuts for any young writer are excruciating. Everything about your script — every flat character, every lousy throwaway line, every unnecessary parenthetical — feels personal and inviolate, gifted from the heavens and written in stone, like some multimedia take on Moses’ holy tablets.

“Change something? Why? It was plenty good enough for you to buy it in the first place, wasn’t it, douchebag?”

Some version of this is what the working writer yearns to bark in his benefactors’ (read: torturers’) faces. If you loved it enough to put real money behind it, why in the fuck do you want to change every last thing about it now? Why date a tall, skinny brunette if you really wanted a short, squat redhead? Where’s the logic in that?

This mentality is, of course, completely understandable. The script is quite literally your baby, your winning Powerball ticket, the lone vehicle by which you hope and pray to escape the nagging self-doubt and just-getting-by poverty of a middle class kid with a mountain of student loans. This is your shot — perhaps the one and only shot you’re gonna get — and if it’s mishandled somehow, if somebody shits the bed and drops the ball, you and you alone will pay the ultimate price for that.

On the other hand… there’s a couple big problems with sticking by your guns every damned time. One, without question, you’ll be replaced as soon as your steps are up, and most likely won’t work for that company or any of those people again. Producers hate writers as it is, see them as largely unnecessary evils. Certainly nobody wants to work with a “difficult” one sitting in meetings with his or her fingers jammed in their ears.

Two, and this can be a tough one for us writers to swallow, what if all these developmental numbskulls are actually right??? What if a few of those “shitty notes” you keep bad-mouthing to friends turn out to be gems, pure gold, BIG IDEAS that help take your script to that hallowed “next level”? Some writers are so busy being defensive that they’re throwing away the very ideas which can dramatically increase their odds of success… and survival.

So John, you ask, how in the hell do I know when to do what? How do I discern between the gold and the gravel, the shit and the pony? How can I insure I do the right thing creatively while traversing such treacherous industry tundra?

And that, my friends, is the eternal question every writer faces, every time they book a gig. Because there aren’t any right answers one-hundred percent of the time. The whole endeavor is entirely subjective, a complete crapshoot, with the looming possibility of some ravenous tiger waiting to bite your head off behind every corner.

Your creative action — or inaction — affects not only this project, but the possibility of the many unseen projects yet to come. Of prominent producers and execs putting in a good word, greasing the skids for a full-freight first draft at 100% of your quote… or not. Of you being able to pay off those loans, buy your hard-working parents a house of their own, live the creative lifestyle you’ve always dreamt of and suffered so damned much trying to actualize…

Best advice I’ve heard? “You’ve got to choose your hills to die on.”

But hey, no pressure, right? Best of luck on those pages.

* * * * *

Spring of 1999, I was coming off saving a film for a big studio. My stock was high and I was starting to make my first legitimate splash.

After years of obscure, unpaid laboring, I was really feeling it, finally discovering my groove. All that “woodshedding” had vastly improved my writing. It was becoming much better crafted and far more intuitive. Better still, proof of this breakthrough was now coming across on the page, for anyone and everyone to see.

A hungry young agency saw it and took me on, and they had enough juice to start getting me into the right rooms. As every artisan in Hollywood knows, if you can’t get into the room, you sure as hell can’t get the job. My new agents totally had my back in that department and very quickly it became plug and play — they’d send me out, after that, everything else was on me. As you might imagine, this was a really good time for a young writer.

So… as a last ditch effort, the big studio had hired me, and against all rational odds, I’d saved their movie. Not only that, but to everybody’s further surprise, it became a big hit.

In this town, you always strike while the iron’s hot. My agents quickly set me up with a very famous director, one of the old school legends, in fact. There was a new company in town spending real money, and he’d set up a project there. All they needed now was a writer.

We met on his studio lot, the Director and I immediately hitting it off. This guy was a blast, regaling me with wild tales of ’70’s Hollywood, each more x-rated hilarious than the last. These were the classic movies I’d grown up with and deeply loved, back to front I knew them all. Now here I was talking to the guy who’d actually made some of them! For a good hour we jawed warp-speed, then spent maybe ten minutes talking broad strokes about his project. It was to be a modern-day Robin Hood — the big twist was casting a famous Brazilian MMA fighter as the lead and setting it in the violent ghettos of inner city L.A.

Now remember, this is ’99, way before the whole MMA/UFC thing fully turned the corner. But within two years, Dana White and Co. would radically reinvent the marketing of that world and find themselves sitting on a multi-billion dollar business.

So in a way — even though it wasn’t on purpose — the Director’s idea of casting an MMA superstar with international appeal in a kick-ass action film was perfectly timed. By the time it was ready to roll out, the U.S. would be beginning its new love affair with the UFC. And we’d be standing there waiting with lightning in a bottle, boffo box office certain to ensue.

I drove back home. Two hours later (just two hours!) my agent calls. Business affairs from this new company had called and made an offer — $100K against $275, or 100/275 in film biz parlance. The Director was crazy about me and knew immediately I was the perfect guy for the job. Just like that it became a spontaneous four-way love fest; Company, Famous Director, Agents, Me. My cup runneth over with this highly-addictive first burst of adulation.

It was pretty hard to wrap my head around. A guaranteed ONE HUNDRED THOUSAND DOLLARS for drinking a free bottle of Evian and listening to one of Hollywood’s most successful filmmakers tell epic war stories? For just being (GASP!) me???

Abruptly, the lightbulb went on. So THIS is what everybody was chasing. Everyone knew there were heaps of money to be made — Monopoly money, from where I was standing. But what about having all the heavyweight ego-stroking a film-addled shut-in like myself could desire? Wasn’t that shit awesome, too?

Next came a company meet-and-greet to discuss our collective vision for the project. My honeymoon continued unabated. We were all on the same page! We all agreed EXACTLY what this film should aspire to! From the top down, everybody on-board was euphoric with developmental glee!

Our homage to Robin Hood would be set in the impoverished jungles of East L.A. Our Lead, forced to flee Brazil because of his heroic actions against homicidal police, would join his Uncle in L.A. to start building a new life for himself. But after witnessing dehumanizing oppression in the sweatshops, and running afoul of local gangsters who violently extorted and terrorized the good-hearted (but powerless) immigrants who had befriended him, our Lead is compelled to take the law into his own hands, seeing justice done, whatever the cost. I was urged to think of the story as gritty, raw and realistic — “Robin Hood ’99” if you will, with someone like Jay-Z playing Friar Tuck.

Robin Hood is one of the oldest legends in all of Western Civilization, and for good reason. The timeless themes of rich vs. poor, the corrupt haves vs. the honest have-nots, still speak as loudly to audiences today as they did in Medieval times. So our ripped-from-the-headlines take involving sweatshops and immigrant labor, oppression and cultural inequality, would fit perfectly alongside the honorable intent of the original.

After a few frenzied white-guy high-fives (“I love this guy!” from one goofy exec), and another complementary bottle of Evian, I was sent off to knock out a treatment so we could quickly proceed to first draft.

* * * * *

Ensconced back in my bungalow, I set about creating my masterpiece. Like I said, I was totally in my wheelhouse at this point, doing the very best writing of my young career. I buckled down and poured my heart and soul into the idea. I skipped concerts, cancelled dates, ate nothing but bad Chinese and Mexican delivery. Day and night, I labored to make the story not just a kick-ass MMA thrill ride — the essential dynamic of the entire project in the first place — but a film which would actually have something to say as well.

I saw it as a classic have-your-cake-and-eat-it-too opportunity — killer action and ultra-cool, franchisable genre characters, with a timely message to the contemporary audience nestled behind all the head-butting and hard talk.

Listen, end of the day, if all you wanted was to see somebody’s trachea stomped into tomato soup, or some asshole’s nutsack blown off, yeah, you would get that in spades. I mean, this was a MOVIE afterall, mass escapist entertainment. But for the more discerning genre lover (like myself) there would also be a legitimate subtext they could hang their hats on. A little something… more.

One month later I submitted my twelve-page, single-spaced treatment. I was anxious, but extremely confident. Never had I felt better about the work and what I was trying to accomplish. I believed it awesome that Hollywood execs were willing to push for a meaningful story, even within the confines of a tiny little genre pic like this. Maybe the self-serving, head-up-ass development stereotypes I’d been brutalized by before would be proven wrong this time around.

A week passed. Then a second. Neither my agent nor myself heard so much as a whisper.

Believe me, if there’s anything a writer learns in Hollywood, it’s this — the silence is deafening.

Silence is never good. Silence says disinterest, displeasure or — scariest of all — disappointment. When you put finished pages someone paid for in their impatient little palms and they don’t get back to you a.s.a.p. something is terribly and irrevocably wrong. In my experience, there are no exceptions to this rule.

Sure enough, start of week three we finally got word. It wasn’t good. Let’s just say nobody loved it. The company didn’t hate it initially, per se, but the Director’s people did. They loathed it with a passion. Which meant the company had to start hating it as well.

Judgment Day came in the company’s flagship conference room. Picture a Hudsucker Proxy-sized oak conference table, all five of my company inquisitors massed at the far end, and me — best of intentions, isolated, confused — docked in a half-mast Aeron chair at the other.

The Head of Development led the prosecution. He was a real trip, an IMAX D-Guy Cartoon, 3D cells brightly penciled in by Pixar. We’re talking Aliens level development exec here, with him playing the egg-laying Queen, not one of the day-player xenomorphs. For the safety of all involved, let’s call him Producer X.

“This treatment is too preachy, too grim, too goddamn G-L-O-O-M-Y,” his first salvo whistled across my bow. “Where’s the fun in this world, John? The Lethal Weapon III of it all? The wink-wink, the hijinx, the Wow Factor?”

Where’s the fun in… illegal immigration? In the callous rich taking advantage of the struggling poor? Is that what he was asking?

“Look, John, trust me — it’s not THAT BAD down there. There are plenty of happy stories to tell. Happy stories which give those people plenty of hope.”

Whoops. My Spidey Sense began an ugly twitch. “Down there.” “Those people.” This couldn’t be going anywhere good.

“To some, you know, this might sound controversial. But I’m going to go ahead and say it anyway, ’cause frankly I’m not a P.C. person and I don’t give a damn,” Producer X leaned forward now, Sunday smile, as if confiding in me. “You know what? I have a maid, and she’s an illegal. That’s right. An illegal. And guess what, John? She LOVES working for me. Loves it! She couldn’t be happier!”

“Me too.” The famous director’s D-Girl piped up. “My husband and I have an illegal nanny. Always smiling, that woman. Very Zen.”

“In fact,” Producer X blazed on, “Recently I had a bit of a funny conundrum. My maid’s daughter was having her quinceañera, and she told me they didn’t have enough decorations for it. So guess what I did? This is great — I let her go around the house and gather up all the old flowers that had been there a few days and take those to the party! Isn’t that terrific? She was soooooo happy.”

There was one exec in the room I’d met before, a good guy, coming from the right place. I watched the same horrified shockwave blitzkrieg across his face that I already wore on mine. So they weren’t all Replicants, I thought. Thank Christ.

Oversharing kills. No doubt, I’m every inch as white boy as the next white motherfucker out there. But there was one huge problem.

I wasn’t that kind of white.

Both my mother and father had Ph.D.’s from Teachers College at Columbia. Their specialties? Education for Gifted Minority Students. My girlfriend was Hispanic, a social worker born literally — true shit — in a dirt-floored shack in Pacoima. So yeah, this probably wasn’t going to work out too well.

All this time, Scriptshadow Reader, I’d been racking my brain, trying to figure out why they hated my treatment so much, why everyone was acting like I’d totally butt-fucked the pooch on this one. Now it hit me full-force — my pages were too, well, Robin Hood. I’d done exactly what we’d agreed upon, gotten it pitch perfect… which was criminally out of tune for these folks.

Class struggle? Rich vs. Poor? What was I thinking? They envisioned our heroic Brazilian as a grubby street urchin, crashing Beverly Hills parties, stuffing his shirt with hors d’oeuvre and stealing thick wads of cash from mink coat pockets. Which is precisely the take they pitched me.

Everything quickly became a vague blur, Charlie Brown’s teacher shot-gunning syllabic nonsense. The only part I remember was Producer X’s take on our protagonist — “It’s like Ché Guevara. He was sexy, he was hot, did a couple of cool killings. Cinematic stuff, right?”

Talk about mind-fucks. Their collective brainstorm now was to take the Robin Hood out of Robin Hood. Regrettably, it was kind of, well, getting in the way.

Meeting over, we shook hands with the nauseous smiles of strangers who’d eaten the same rotten shellfish. I grabbed my ’66 Bug — the same car I’d driven out to L.A. eight years earlier — and puttered straight up Wilshire to my agent Marty’s office.

When I walked in, I just unloaded. Play by play, line by line, vomiting up details of the nuclear winter I’d just lived through. From Marty’s expression, I could see he was having trouble making sense of it all. He knew my background, knew the guy I was, but still. After I’d slaked my desperate need to rant, I punctuated things with this cute little gem —

“They can keep the money,” I said. “I don’t want it.”

In Marty’s entire life, I don’t think a single client had ever told him that. And why would they? Idealism and moral outrage are the privilege of a rarified few in this Biz. At the grunt level, the level I was at, those concepts played worse than kiddie porn. Besides, who the fuck was I? Claude Rains in Casablanca? “I’m shocked, shocked to find that half-baked racism is going on here!” It’s not like I’d signed up for the Peace Corps or anything.

Still, I had my principles, and I was willing to put all that Monopoly money where my naive pie-hole was. Marty’s advice was to go home, cool my tool and let him do some reconnaissance. Once he’d sussed things out, he’d get back to me.

Two things bailed me out. First, the exec I knew called Marty and totally vouched for my eyewitness testimony (told you he was a good guy). Second, Producer X himself knew how badly he’d fucked up and called trying to smooth things over. “Listen, Marty,” he told my agent, “This is a big misunderstanding. Nobody over here wants to make an… irresponsible movie.”

They scheduled a second meeting trying to salvage things, but in many ways it was worse than the first. My time was spent daydreaming about putting Producer X in a chokehold and pulling a Sharky’s Machine — pile-driving us through the plate glass and then plummeting 200 feet straight down to the pavement below.

So that’s it. The deal died. They paid for the treatment, and I — insisting on principle — left the other $65,000 sitting on the table. SIXTY-FIVE THOUSAND DOLLARS. Just walked away from it. And yeah, it kinda stings to write this, even now.

You may have wondered — what about the Famous Director, the one guy who surely would’ve had your back? Predictably, after that first, glorious filmic dry-humping, I neither saw nor heard from him again. No phone call. No nothing. To this day, I don’t know if he actually hated it, or his D-Girl with the illegal nanny had cut my throat without giving him the real scoop on any of what went down.

And Producer X? Was there any Bad Karma due a producer like that? Would the bold heavens take a stand and angrily smite down what the film industry itself would not?

You’re fuckin’ kidding, right? This is the Film Biz.

A few years later, I was over at some friends’ place watching the Oscars on auto-pilot. About ten hours in, after two dozen absurd dance numbers, they finally got around to Best Picture.

And who should win but Producer X.

This go ’round I did crap my pants. Openly and without restraint. But this wasn’t even rock bottom. Because up next was his acceptance speech —

“I’m soooooo happy you’ve taken my movie into your hearts, this wonderful little film about compassion, racial harmony, the end of prejudice of all kinds, and, of course, hope. Always hope, for all those people less fortunate than ourselves.”

Producer X had just won an Oscar. That’s right. A fucking Academy Award. By playing the “Can’t we all just get along?” card.

Before he even left the stage, I was stumbling into the backyard, begging the hostess for a frenzied bong hit. A writer can only take so much, you see, and my mind was dangerously close to snapping. My only real hope of retaining any sanity now lay in a bright, protective sheen of cannabis.

As I slipped into oblivion, a single thought ran roughshod through my mind —

“I wonder if Producer X’s illegal maid is back at his house watching this, too.”

Carson again. Naturally, I’m asking the same question you are. Who the hell was the producer?? John refuses to name names, but I will find out. Mark my words! In the meantime, head over to John’s Tweak Class Page and sign up for his screenwriting class that starts this January. It truly is a unique opportunity to study with a produced, working writer. You won’t be disappointed!