Genre: Sports Thriller

Premise: A desperate cyclist and his charismatic new team doctor concoct a dangerous training program in order to win the Tour de France. But as the race progresses and jealous teammates, suspicious authorities, and the racer’s own paranoia close in, they must take increasingly dark measures to protect both his secret and his lead.

About: This script finished in the Top 10 of last year’s Black List. The writer, Haley Bartels, seems to have been destined to get to this point. She received her MFA in Screenwriting from AFI. She got a BA in English from UCLA. She studied at the Lee Strasberg Theater and Film Institute in New York. She studied at Russia’s premiere school for the dramatic arts, the Moscow Art Theater (МХАТ). She made last year’s Blood List. And this script won one of the Nicholl fellowships.

Writer: Haley Bartels

Details: 109 pages

Quoting Macbeth on page 1!

Been a while since I’ve encountered that.

This is just my own personal opinion – this is not a script rule or anything – but I have never, in my life, read a pre-story quote, in a screenplay or a novel, that has enhanced my reading experience. They seem a bit pretentious to me.

Curious to hear what you guys think about pre-script quotes. Share your thoughts in the comments. Actually, wait up! You gotta read my review first.

Taylor Mace lives in Boulder, Colorado and is a professional bike racer. Just not a very good one. He’s 35 years old and in denial about the fact that each year that passes, he’s getting worse. At the moment, he’s barely clinging to the bottom rung of the team he races for, Inverness.

Meanwhile, his best friend on the team, Duncan, is riding better than ever. He has the kind of talent that Taylor could only dream of. Actually, everybody on the team has more talent than Taylor. Taylor is a work horse. And his horse shoes are starting to splinter.

But Taylor is given a second chance when 40-something Andrea Lathe joins the team. Andrea is one of these medical sports doctors who look for ways to improve athletes by checking their blood, their heart, their entire circulatory system.

Andrea puts the team through a series of tests, including an updated version of The Pit of Despair’s death machine in The Princess Bride. No, I’m not kidding. It’s really the same device. The machine’s purpose is to determine each rider’s threshold to pain. You stay in it for as long as you can.

Taylor finishes last in every single test EXCEPT THE MACHINE. Where he crushes everyone else. He makes it an entire two minutes. Nobody else made it more than 15 seconds. His show-stopping result leads to Andrea Lathe becoming obsessed with him. In her experience, the people who win the big tours in racing are the ones who can endure the most pain.

So Lathe makes Taylor her pet project. Which also means that Taylor needs to start taking steroids. Lathe is extremely manipulative and easily able to talk Taylor into doing drugs. And as soon as Taylor does, he begins racing up the ranks within the team. By the time they get to Spain for the big next tour, Taylor is awarded the number 1 spot on the team.

But Lathe doesn’t stop there. She demands that Taylor LITERALLY give her his blood. That blood is then sent off to a secret lab where it’s super-metasticized or something, and comes back where it’s re-injected into him, turning him into a super soldier. Once on the mega-blood, he becomes unstoppable. That is until another racer on the team starts challenging him, a rider who may also be under Lathe’s tutelage.

This is a very good script.

Whenever I come into a sports screenplay, what I’m immediately worried about is cliche. Especially if it’s a racing script. I mean how much more cliche can you get than, “I’m going to win this race.” Let me guess. You’re going to be trailing with 10 seconds to go before your second wind magically kicks in and then you’re able to pass him at the turn and beat him in a photo finish.

Pumping Black is anything but cliche. Remember that movie about wrestling called Foxcatcher with Channing Tatum? This reminds me a lot of that movie. But it’s actually good. The reason it’s good is because the central relationship is really sharp.

You’ve got Taylor, who’s so desperate, at the end of his career, that he’ll do anything to win. And then you have Lathe, who’s one of the better characters you’ll read in a script all year. She’s this manipulative evil sex demon who is not afraid to use her sexual dominance to make these men do what she needs them to do.

One of the early scenes is her needing to check Taylor’s muscles so she tells him to strip. He strips down into his boxers and she says, “No, the boxers too.” Then in one of the most inappropriate scenes you’ll read in 2023, she “inspects” him.

It’s weird but it’s also one of the things that sets the script apart. Whenever Lathe and Taylor are alone, the scene is charged with this intense negative sexual energy brokered by an inappropriate power dynamic.

I liked how Bartels also drip-fed the steroids. At first, it was a just a pill. And you could’ve ended there. Only given our protagonist these pills. But the art of writing screenplays is such that you constantly want to add new things to the story. If it’s just this pill the whole time, we’ll be bored by the pill within 20 pages. So ten pages later, we introduce injections. And then 15 pages later, we introduce the big dog – blood swapping.

And what was so great about the blood-swapping was that now you’re introducing the element of death. It’s explained to us that this mega-blood gets a lot thicker, so much so that riders will set alarms to get up at four in the morning to move around to get their blood flowing so it doesn’t get clogged up in their system and kill them.

I love stuff like this. I love when you add multiple consequences and those additional consequences get bigger each time. At first, it’s just getting kicked off the team. Then, it’s possibly getting caught by the doping federation. Then, it’s death!

As I’ve told you guys before, I often judge the quality of a script on the choices that weren’t made. You could’ve easily made Lathe a nuts and bolts male team member. Just by making Lathe a female, she becomes different. Making in her 40s makes her different. Making her Machiavellian makes her different. Having her use her sexuality to manipulate riders makes her different. This could’ve been a lame character in another writer’s hands. It’s a super memorable character in this writer’s hands.

The only reason the script doesn’t get an Impressive is because of suspension of disbelief issues regarding some of Lathe’s more outlandish behavior. Even though I liked a lot of things about her, I don’t know if I bought that she could just make guys strip completely naked, tie them down, attach them to torture devices without warning, and start torturing them. I mean, did #MeToo get lost on the way to the Tour De France?

Still, the actual writing and style is easy to read. Everything here moves fast. The plot developments, while never shocking, always improvedthe story. For example, bringing this young buck, Malcom, in at the end and having him be a potential foil to Taylor’s glory, and also possibly signifying that he’s the one who’s supposed to win and that Lathe may be using Taylor – that whole evolving storyline was very compelling. There’s this terrifying late development of a bad bag of blood that Taylor injects into himself that may kill him. It’s good stuff.

This is, most definitely, a worthy entry onto the Black List.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[xx] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Pumping Black shows us the power of an X-Factor character. An “X-factor” character is often someone who doesn’t act predictably. And that makes them very exciting to watch. I mean, one of the key scenes here is when Lathe asks Taylor to consider getting injections as well. Taylor says no. She says fine, sorry for bringing it up. And then, when he turns, she plunges the needle into him anyway. Lathe is the definition of unpredictable. You can’t really use your protagonist as an x-factor character. But you can use secondary characters, like Lathe.

Genre: Comedy

Premise: A white Jewish accountant falls in love with a black clothing designer and the two must deal with their parents’ unique perspectives on their relationship.

About: Kenya Barris, the creator of Black-ish, is finally getting into the feature film game with this script he wrote with Jonah Hill. The movie premiered on Netflix this Friday. The film has a killer cast. Jonah Hill, Eddie Murphy, Julia-Louise Deyfuss, David Duchovny.

Writer: Kenya Barris and Jonah Hill

Details: 2 hours long

COMEDY!

They say it’s dead.

At least at the box office.

But maybe not at the streaming office.

This is one I’ve been looking forward to since I saw the trailer, which I thought was great. I loved the casting. Fun premise. What could go wrong?

Ezra is a 35 year old Jewish accountant who hates his job. The only respite he gets from it is through the podcast he shares with his black lesbian plus-sized best friend who he discusses black culture with. In Ezra’s dream world, he would quit his job and podcast full time.

But first Ezra would like to fix his love life, or, I should say, his lack of one. Although the Jewish community fixes Ezra up with a lot of girls, he can’t seem to find one that he vibes with.

Then, one day, after work, he gets in an Uber that isn’t his Uber, which is where he meets Amira, a young black fashion designer. Amira is angry that Ezra would get in her car, assuming she must be an Uber driver because she’s black, until he shows her the picture of his driver, who she admits looks exactly like her.

The two start joking around and, before we know it, they’re dating! Months pass, Ezra is head over heels. So he asks her to marry him. She’s totally down but before that can happen, they must meet the parents.

First, Ezra meets Akbar and Fatima, Amira’s parents, and right away there are issues. Neither of them like the fact that their black daughter is marrying a white man, particularly a Jew, with Akbar leading the charge. When Ezra asks Akbar for his blessing, Akbar simply says, “If you want to marry my daughter, you can try.”

Ezra’s parents are the opposite. They are beyond excited that they are about to up their “progressive” street cred. Ezra’s mom, Shelley, is particularly thrilled that she will have half-black grandchildren. Shelley and Arnold (Ezra’s dad) start to creep Amira out with just how much they love her blackness.

Things get even crazier when the parents have to meet EACH OTHER. Right away, they’re debating who had it worse, slaves or Holocaust survivors. And now we’re off to the races. The friction gets so intense that maybe it’s going to prevent Ezra and Amira from living happily ever after. Ultimately, the couple will have to decide what’s more important, their happiness or their families’ approval.

I have never experienced a Kenya Barris production before. And after watching this, I’m on the fence whether I’ll do so again.

It’s not that You People is bad. It’s that it’s frustratingly uneven.

At times it’s cheesy. Other times it’s awkward. And at certain times it feels so much like a sitcom that I forgot I was watching a movie. There is one scene where there are 6 chairs set up in a perfect U-shape and every character is sitting in a chair and they have one long conversation. No movement at all. Just people on a set saying their lines. It truly felt like Barris was learning on the job.

Luckily, the script works well whenever it’s leaning into its concept, an interracial couple facing both overly skeptical and overly accepting parents. Ezra’s attempt to get to know Amira’s parents by scheduling a meeting at Roscoe’s Chicken and Waffles (a popular black eatery in Los Angeles) was pretty darn funny.

But my favorite scene was Amira meeting Ezra’s parents. Shelley’s intense desire to impress Amira with how much she loves black people was hilarious. And Arnold’s bizarre obsession with his favorite rapper as a teenager, Xhibit, begins one of the best running gags in the movie.

I think my favorite joke was when Ezra left the room to calm his mother down only to come back to find Arnold [badly] serenading Amira on the piano, which he clearly never used until this moment.

Unfortunately, whenever the movie moves away from that premise, it falls apart. The ‘falling in love’ scenes, in particular, are hard to watch. I struggle to think of a more inauthentic example of two people falling in love. From cheesy R&B tunes to 1980s dissolves to some pretty lousy “I love you, no I love you” dialogue.

One thing that stuck out to me as a considerable blemish on the film was Ezra’s dream to become a professional podcaster. He has this podcasting partnership with a black lesbian (or potentially non-binary person?) that felt about as authentic as Kanye West running a self-help seminar.

Nothing about their partnership rang true. You didn’t buy into their friendship. You knew there wasn’t any scenario by which Ezra would’ve ever met this woman. The only reason it existed is because the writer wanted it to. And when you, as the writer, prioritize your ‘wants’ over writing the actual truth, that’s when the pillars holding your script up start to splinter.

Worse, turning this podcast into a profession as opposed to a hobby didn’t seem representative of the character at all. Ezra didn’t appear to have any other black people in his life before Amira arrived. Based on his friend group we meet later at the bachelor party, he hung out in exclusively white circles. So why was he interested in black culture to the point where he went out and found a black non-binary podcasting partner to talk about black culture??

Why am I getting all nerdy about this? Because you never want to force things into your story to begin with. But you especially don’t want to do it in comedy, where you’re avoiding anything that can restrict the oxygen breathing air into your comedy. Forced storylines and the exposition that comes with them can inject a clunkiness into scenes that then becomes the dominant attribute we’re noticing.

Which is exactly what happens here. Every time Seth’s talking to his podcasting partner, all we’re thinking is, “These two have no chemistry. Where did they meet and why are they friends? Their podcast is lame. There’s no future in this.” And if we’re thinking about that, guess what? We’re not laughing.

Hollywood’s been getting character jobs and character job motivations wrong for decades. The main reason for this is that writers never have real jobs. So they have no idea how the real world works. This leads to them giving characters jobs *they would like to have* or whatever job is hot at the moment (why so many 80s characters in rom-com scripts were architects).

This is why, of course, Seth is a podcaster. Because everybody’s a podcaster these days. It’s “relevant.” I cannot emphasize enough that this is not how you should choose your hero’s job. Your character’s job (as well as whatever dream job they might want to quit their current job for) should always stem from who *your character* is, not from who *you* are.

With comedy, you have two options. One is to lean exactly into who your character is. Two is to give them an ironic job. So let’s say your character is an overly relaxed person who’s good with people. He could be a therapist. Or, if you wanted to be ironic, he could be a chef at a very intense kitchen where he’s screaming all day. But what he wouldn’t be is a bitcoin market analyst, aka some random trendy job that doesn’t match his character at all.

They say comedy is reacting and both Joanh Hill and Lauren London’s reactions are probably the best thing about this film. Julia Louise Dreyfuss’s Shelley wants so desperately to be accepted by the black community that she is constantly over-stepping and saying stupid stuff. At one point, after learning that many black women wear wigs, she does some research so that the next time she sees Amira, she can say, “I love your hair. It’s so pretty.” “Thanks.” “Is that a roller set?” The look on Amira’s face as she stares back at her is just priceless.

But the best is Ezra listening to his mom and dad try to sound hip when he first brings Amira around. Arnold, for reasons that nobody understands, starts to share his love for Xhibit, a rapper from the late 90s, the last time he listened to rap. Watching Ezra fall apart as his dad goes further and further down the Xhibit rabbit hole was one of my favorite parts of the movie.

I hate grading on a curve but I feel like the world of comedy has fallen so drastically that we’re lucky when we get a comedy that even kind of works. Which is how I’d categorize You People. It kind of works. And it did make me laugh out loud over a dozen times. That’s something, right? So, if you’re looking for a little cheer-up, this movie will probably do the trick.

[ ] What the hell did I just watch?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the stream

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: When you have a good concept, structure as many scenes around that concept as possible. You People is best when the characters are around their parents. That’s where all the conflict and fun is. It’s at its worst in almost every other scene.

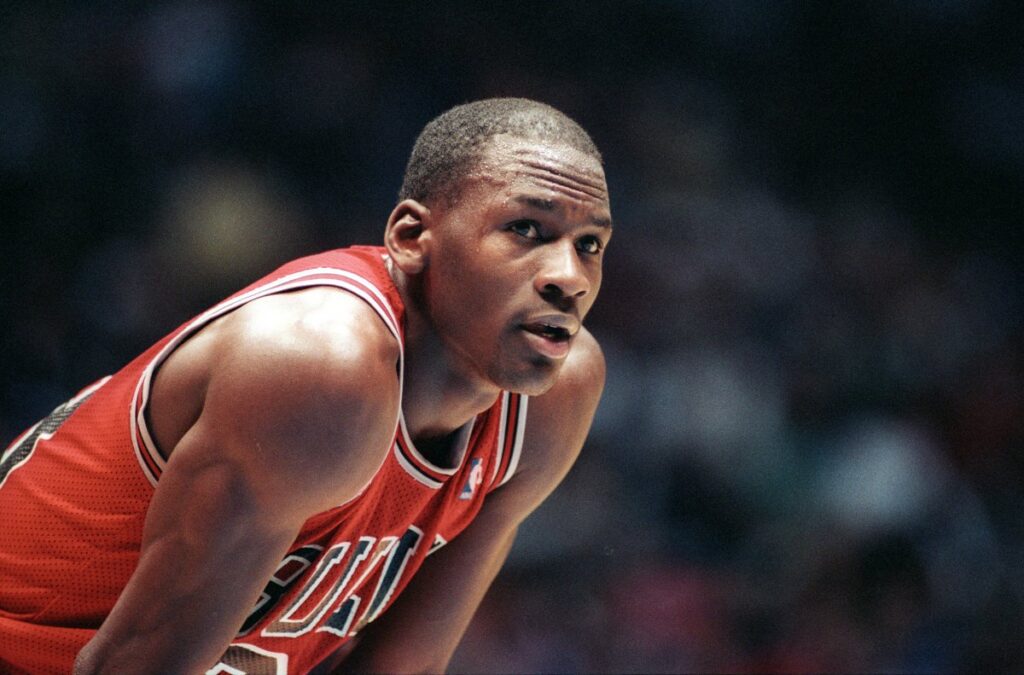

Hey, Jordan didn’t make the cut of his high school team either. So if you’re on this list, it may be a good thing!

Hey, Jordan didn’t make the cut of his high school team either. So if you’re on this list, it may be a good thing!

This is a reminder that on the second to last Friday of every month, we’ll have a logline showdown here on the site. Send your title, genre, and logline to me at carsonreeves3@gmail.com. I’ll vet the best five, put them up on the site for competition. Winner gets a review the following Friday (so your script has to be written!). The next deadline is Thursday, February 16th, 10pm Pacific Time.

Unfortunately, not every logline can be a winner. So in the spirit of both teaching and making sure that everyone doesn’t keep sending me loglines that have no chance, I’m featuring 7 loglines that will not make the Amateur Showdown cut. If you entered with one of these, learn from your mistakes, and enter another showdown with a fresh concept. We’re doing these all year long so you have time!

Title: HAVE YOU SEEN ME?

Genre: Thriller

Logline: Disturbed by the disappearance of a pretty blond white girl overshadowing that of her black best friend, an 11-year-old white girl fakes her own disappearance in hopes of it leading authorities to her friend.

Analysis: I sort of understand what’s going on here but it’s one of those ideas that’s not quite formulated when you lay it out. And this is a challenge that a lot of writers run up against. These ideas that *kind of* sound like movie ideas. But if you actually break down the logline, they don’t make sense. In this case, we’re exploring the well-documented phenomena that the news only reports on pretty young white girls that go missing, never black girls. So our hero fakes her disappearance… to make people look for her black friend. Wait, hold on, what?? How does her going missing get people to look for her friend? Aren’t they only going to look for her? And doesn’t that only solidify the ‘missing young white girl’ phenomena? Maybe she leaves messages for the cops like, “Don’t forget my friend who’s also missing!” I don’t know. It doesn’t make sense to me. And a logline MUST MAKE SENSE. Let me say that again. A logline MUST MAKE SENSE. You don’t get to explain your logline to someone. They just read the logline. So IT MUST MAKE SENSE.

Title: Office Murder Mystery

Genre: Mystery

Logline: Waking up in a locked office next to the dead body of his boss, a man suffering from a schizophrenic disorder must find the real murderer by the end of the business day with the help of his five favorite dead mystery writers that only he can see, hear or speak to.

Analysis: This one comes from a longtime reader of the site, Alex, who I really like. But this logline doesn’t work for me. It definitely has a high-concept feel to it. But two things are keeping me away. One, whenever you start talking about schizophrenics, the writing level needs to be 10 times that of a normal writer. It’s a very specific disease and in order for it to come off as authentic, the writer really has to understand it, and in my experience, 999 writers out of 1000 don’t. So it always ends up being lame. Also, the “dead mystery writers” thing comes out of nowhere. One second we have a dead body of a boss and the next we have mystery writers??? Where did these mystery writers come from exactly? I know. They’re in his head. But they’re not set up well. We weren’t told that our hero was a vociferous reader or an aspiring novelist. Just a “man.” So there’s zero connection to the mystery writers component. For these reasons, the logline doesn’t work.

Title: Eagle Heart

Genre: Period drama – WWII

Logline: When his father comes home from war without legs and without hope, a nine year old boy believes that by saving a dying bird he can stop his family from falling apart.

Analysis: These are always hard for me to turn down because I can tell the writer has written a very heartfelt story that he cares deeply about. But the logline still has to work. A big problem I’ll see in a lot of loglines is that the writer makes a HUGE leap from one dot to the next. A ton of necessary information in between is skipped over, making the logline seem awkward and disconnected. We start out with a dad coming home from war, injured and hopeless. Okay, so far so good. Then we’re saving a bird. Wait, what??? What about saving dad?? Then we find out he’s saving the bird so that his family doesn’t fall apart. What about saving the bird to save his dad!!?? All three sections of the logline do not operate in harmony, which is why I passed this one over.

Title: SINNERMAN

Genre: Horror

Logline: When a home invasion ends in murder a mother of two young children is ‘haunted’ by the intruder’s malevolent spirit but she soon discovers that she’s the undead and is being held in purgatory…

Analysis: First of all, when a writer hits me up with 4 or 5 submissions, I pretty much don’t trust those entries. As writers, we typically have 1 or 2 screenplays that are RIGHT NOW our best work. We do not have five equally good scripts. Three of those are older work and not nearly representative of what we’re capable of now. So if you’re just spamming people with your five most recent screenplays, chances are you’re not really trying to show someone your best work. Hence, I wouldn’t use this strategy (on my site or anywhere else). As for the logline, it has a bunch of those buzzwords that make it sound like a movie (home invasion, haunted, undead, purgatory) but nothing unique to help it stand out from the pack. A script idea usually needs a unique attractor of some sort. This one doesn’t have one.

Title: WEIRD WAR

Genre: Epic Vietnam War Era Supernatural thriller

Logline: A young grunt in denial about his psychic ability is assigned to an elite squad of spirit hunters and is forced to come to terms with his family’s own supernatural past.

Analysis: If you follow my site, you know that extended genre descriptions take you out of the running immediately. You want one genre descriptor, two at most. In very rare situations, three. But whatever you do, you don’t want to add things into the genre description (Epic, Vietnam Ear Era) that aren’t accepted known genres. Not only does it come off as unprofessional, but it indicates that the script is all over the place. So, what do we see with this logline? Well, it sounds all over the place. Psychic abilities. Spirit hunters. It sounds out there and, based on my extensive experience reading scripts, like it’s going to have a very wonky and muddled mythology. Now, could I be wrong? Of course. But this is what my experience tells me is coming, which is why the script didn’t make the showdown.

Title: Edge of Humanity

Genre: Sci-Fi

Logline: Earth faces the final stages of environmental collapse from climate change. The global government secretly commits genocide to avert human extinction, while rival factions fight to uncover the truth.

Analysis: First of all, this writer sent a nice e-mail saying that he recently received his first “RECOMMEND.” So good on him! But, when it comes to Logline Showdown, the recommends are rarer than snow in Los Angeles. We’re tough graders here, and the problem with Edge of Humanity is that the logline is way too broad. There isn’t a single mention of a character. So who do we connect to? And what’s the actual story, since presumably we’re going to be following someone on a journey? On top of that, the broad strokes are too generalized and don’t set the script apart. More generic buzzwords: “environmental collapse,” “climate change,” “global government,” “genocide,” “human extinction.” It just sounds like a million other scripts, movies, and tv shows. This is your monthly reminder that a logline should not be about what makes your movie SIMILAR to others. It should be about what makes your movie DIFFERENT from others.

Title: Controller

Genre: Sci-Fi

Logline: A young fugitive, still traumatized from a high school assault, uses an experimental mind-control device to save a new lover from a jealous techno thief.

Analysis: This logline has several problems. For starters, the high school assault should not be in the logline. That’s backstory. It doesn’t add anything relevant that we *need* to know to understand the story. From there, you have “experimental mind-control” and “techno thief.” These are two major aspects of the logline and they don’t go together at all. The featured words in a logline MUST CONNECT for your logline to feel whole. So, for example, if you say your hero is a vegan, then it works well if, later in the logline, they find themselves in a slaughterhouse. Finally, I don’t really know what a techno thief is. You mean like they steal bitcoin? It feels like a dated word and it’s not clear enough all on its own. If any word in your logline has a chance of being even mildly misunderstood, you don’t want to use it.

Carson gives logline consultations for $25 a pop. E-mail him at carsonreeves1@gmail.com if interested.

Genre: Action-Thriller

Premise: After an ex-Marine turned lawyer sees that he’s been reported dead in a local car accident, he gradually learns that he’s the target of someone involved in a top secret government program.

About: Million dollar sale back in 1993 to Arnold Kopelson, the producer of The Fugitive. Christine Roum, the writer, still writes today, 30 years later. She’s currently writing on the show, Big Sky.

Writer: Christine Roum

Details: 121 pages

Would he still do it? The Seagalaissance?

Would he still do it? The Seagalaissance?

This one has a fun backstory.

It was sold for one million bucks back in 1993. Once The Fugitive debuted, the script got a hard push to become a female version of the hit movie (wait a minute, is this 1993 or 2023??), with the hope of it starring Jodie Foster or Geena Davis.

Ah, but then Hollywood enigma Steven Seagal somehow got a hold of the script and, all of a sudden, he wanted to make it. So the film was completely rewritten from a female to a male lead (check that – DEFINITELY not 2023).

Because Seagal duct-taped himself to Everglades trees and became impossible to contact, the project stalled and, unfortunately, never got made. But the script is supposed to be good and, since it’s a member of the ageless action-thriller genre, could probably be made today!

Let’s see if it’s any good.

Nick, who’s almost 40, is a lawyer in Washington D.C. We can tell Nick is different because while everyone else wears suits, Nick is just fine in cheap jeans and a ratty sports jacket. When we meet him, he’s helping an old reporter buddy of his, Jay, get off for some invasion of privacy charge. Jay rides right up next to the law whenever he investigates a story and so Nick constantly has to bail him out.

Afterwards, Nick reluctantly lets Jay borrow his car, as Jay’s got another story he’s chasing. But he says something chilling before he leaves. “If I die, it wasn’t an accident.” Nick notes the odd thought but doesn’t think much of it until later that evening, when he turns on the news and sees that Jay died in a car crash. Oh, and that so did Nick!

Nick, determined to correct this mistake, goes to the local police station where a buddy of his works and explains the situation. His buddy, though, looks very surprised to see him. Not just in a, “I thought you were dead in a car crash” way. But in a “You should not be alive right now” way. Nick senses this and makes a run for it. The cops start shooting at him and that’s when Nick knows for certain: Someone wants him dead.

Nick heads to an old lawyer girlfriend of his, Delia, who hooks Nick up with a lawyer she knows, Avery. The three decide it’s not safe to be in D.C. right now and head out of town. But on the toll road, Nick can’t help but keep looking in the rearview mirror at Avery and thinking something funny’s going on. At the toll booth, Nick leaps out of the car and both Avery and Delia start shooting at him.

Holy SH-T! Everyone wants Nick dead!

After being betrayed by several other friends, Nick goes back to an older girlfriend, an electrician named Casey, who has zero ties to D.C. Casey, still burned by their failed relationship, isn’t exactly thrilled to hang with her old beau, especially under these circumstances. But together they do some digging and find out that Jay was looking into some deep government program and the assumption is that Nick now knows about it too. So Nick will have to find out what this program is and expose it in order to save his life.

It was funny reading this script as I felt like I’d been taken back through a time warp. Right from the start, I could sense a different attitude towards script writing than I do today. The writer really REALLY wants you to turn the page. And it’s effective.

We’re at some remote lab and this seemingly innocuous woman walks up and just BAM shoots another woman in the face. We then cut to a security camera where we’re seeing some guy walking through another area of the lab and he JOLTS. A split-second later he falls. The same woman walks into frame, gun raised.

There was something about this all being done by a mild-mannered woman that surprised me and pulled me in. I now wanted to keep reading. And hence, how screenplays used to be written.

These days, there just isn’t that sense of urgency. The writer doesn’t seem nearly as worried about losing the reader. The reader needs to respect the time and attention *the writer* put into this script. The *reader*, in the 2023 writer’s eye, is the one who owes *them* their time. And it’s this attitude that leads to so many boring scripts.

Now you may be thinking I’m about to award 90s scripts, and this one in particular, the gold medal in screenwriting excellence. But the truth is, Dead Reckoning displays both strengths AND weaknesses of that era. The biggest weakness of those 90s big spec sale scripts is that they were all soooooo generic. There was very little innovation.

Blah blah blah some sort of political conspiracy. Blah blah blah a dozen generic chase scenes. Even when Dead Reckoning tries to differentiate itself, introducing a struggle inside a wacky machinists’s lab, it doesn’t feel right. It was almost as if, in an attempt to prove that they weren’t going to make this COMPLETELY cliche, they added this bizarre location. Except that it was so random, so disconnected from the rest of the script, that it didn’t work.

It’s one of those things rarely talked about in screenwriting. A random unique location isn’t proof that your script is different. Your locations, your scenes, still have to organically evolve from the story you’re telling to hold water.

This contrast makes Dead Reckoning very hard to judge, its familiarity constantly interjected with a dogged determination to keep the reader turning the pages. To that end, Dead Reckoning may have the most untrustworthy cast of characters ever. No one can be trusted, even former years-long girlfriends. There are so many people who try to kill Nick that the later scenes play out with tons of tension even when the writer isn’t trying to add any. We keep waiting for the shoe to drop. And it definitely infuses the script with a relentless energy.

Good, right?

Okay, but now quiz me on what the actual cover-up is in Dead Reckoning.

I DON’T KNOW.

Even though a good four scenes were dedicated to explaining it.

Again, 90s scripts seemed so uninterested in answers. They were more focused on the questions, on the mystery. And it sucks. Because one of the best moments in the script is when Nick turns on the TV and sees that he’s dead. And then, a few scenes later, when he goes to the cops, they look at him not as they’re happy he’s still alive. But that Nick isn’t supposed to be alive. And they’re going to finish the job.

That kind of extreme need to kill this man necessitates a kicka$$ explanation. If he needs to be eliminated to take care of a cover-up, then give me a great cover-up. Not Generic Black Contract Army Navy Secret Weapon Something-or-Other Cover-Up that’s in every script.

The Fugitive, which this script wants to be, didn’t have a mind-blowing explanation of why Richard needed to be framed for his wife’s murder. But it was very well plotted, constructed, and made sense. His wife’s work was threatening a very big release of a medical drug.

The truth is, most scripts written back in the 90s were front-loaded. They came in with big splashy first acts (you turn on the TV to see that you’ve been reported dead) and had no idea where to go from there. Which is why most of them devolved into the same type of third act that you see here. Some governmental program-weapon conspiracy.

And, honestly, I think this is why the spec boom died. Cause you had a whole bunch of great first acts but very few great second and third acts. So when all of these movies bombed, Hollywood said, “Enough is enough. We need a better model.” And they moved over to IP.

With that said, I don’t dislike these types of scripts. In fact, I love them. And the genre is always going to be in favor. What fits better into the movie format than thrills and action? But you have to write a good script. You have to write a COHESIVE script. You have to put just as much energy into acts 2 and 3 as you do that grabber of a 1st act. It’s not easy. But it can be done!

Script link: Dead Reckoning

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: A great way to set up a character is to have them dress completely differently from the standard uniform that everyone else wears. Nick wears grubby jeans in a field of people who wear 2000 dollar suits. You can do the opposite of this, too. If everyone wears normal clothes, have your character wear a suit. Anything that stands out from the norm helps us identify your character. Also, characters who stand out in some way pop off the page better.

Genre: Comedy

Premise: Four women in their 80s who have built a weekly routine of watching Patriots games decide to travel to the Super Bowl together so they can see Tom Brady win, what they believe, will be his final Super Bowl.

About: When Tom Brady retired, he immediately set up the first movie for his brand new production company. This is that movie. It’s written by Emily Halpern and Sarah Haskins, who are best known for writing the female Superbad, “Booksmart.” However, as often happens in Hollywood, Halpern and Haskins were rewritten by the director, Kyle Marvin, and Marvin’s producing partner, Michael Covino. Up until this point, Marvin and Covino have written a small TV show called “All Wrong,” and an indie movie about a couple of biking friends called “The Climb.” I’m guessing the friendship portrayed in “The Climb” is why Brady okay’d them to make his first film.

Writers: Emily Halpern and Sarah Haskins (rewritten by Kyle Marvin and Michael Covino)

Details: 116 pages

Eagles vs. Niners. Bengals vs. Chiefs.

But no Brady. :(

Wait, what am I talking about? YES BRADY!

80 FOR BRADY!

At first glance, you might say, “Carson, this doesn’t seem like the kind of script you’d typically review. Have you gone loopy? Maybe being so wrong about The Last of Us has infected your brain.”

I’ll tell you exactly why I’m reviewing this. Everywhere I drive these days, I see a big fat billboard for 80 For Brady. And I’m looking up at that billboard and I’m thinking… they’re going to release that movie… IN THEATERS???

Meanwhile, at the end of this week, Jonah Hill is coming out with a new comedy called “You People.” Which I think looks great. However, Jonah Hill’s movie… IS ON STREAMING. Let that sink in for a second. The hip young comedy actor’s movie is on streaming while the movie with four 80 year old women gets a theatrical release.

What’s going on here?

The answer may lie in Tom Hanks’ most recent film, A Man Called Otto. The film is considered a huge success considering that nobody thought it would make 5 million dollars, much less 35 million.

What I think is happening is that the studios are starting to realize that they can still market theatrical movies to people who grew up going to the theater. Whereas, with the younger generation – they’re growing up expecting everything to be on TV. So you can’t really get them to leave the house unless you’ve got a 400 million dollar superhero film.

I think this newfound strategy is kinda interesting and I’m curious to see if it’s going to work.

80 year olds Lily, Carol, Jane, and Julie spend every single Sunday during the NFL season watching the Patriots – and more specifically, Tom Freaking Brady – play. It’s their little ritual. It’s their little group. And for one of them it’s *literally* what they live for.

Their group started back in 2001 when the girls were at Lily’s after she’d been diagnosed with cancer. They all wanted to watch TV but the remote ran out of batteries. So they were stuck – GASP – watching FOOTBALL! As it so happens, that’s the first game that Tom Brady played. And they instantly fell in love with him. Brady then become Lily’s inspiration to fight!

Flash forward to the present and Lily is keeping a big secret from her friends. The cancer is back. And since this may be Brady’s last Super Bowl, she dips into her savings and buys four Super Bowl tickets. Off the four of them go to Houston, where the Pats are playing the Falcons (this is 2017).

Once there, it turns into The Hangover. They participate in NFL activities. They go to exclusive parties. They dance it up with Guy Ferieri! But of course their individual issues pull them apart during the trip. Jane just wants to get laid. Carol needs to break free of her needy husband. Lily keeps dodging her doctor’s calls. And Julie – actually, I can’t remember what was going on with her. Something relevant, I’m sure.

When their excessive partying leads to them losing the tickets, it looks like their Super Bowl dream is about to go the way of a Chicago Bears postseason. They’ll have to find another way into the game. Which, of course, they do. And when the Patriots go down by 25 points, it will be up to one of our four ladies to give Tom Brady the pep talk of his life.

There’s a screenwriting approach that a lot of writers – even professional writers (as we’re about to see) – resort to. It’s called the “Just Bear With Me” approach and it works like this: you know your heroes are going to go on this big adventure for the bulk of the movie. And that adventure is going to be fun.

So, for the first act, you say to your audience, “Just bear with me. I’m going to set up all the characters. I’m going to go through some annoying exposition and backstory. But if you bear with me, I promise you things will get better.”

That’s the approach 80 For Brady goes with. And it’s nearly a script-killer. I mean, I’m sorry, but the first fifteen(!!!) pages of this script are the characters in a room watching a Patriots game. After the game, one of them says, “Remember how this all started,” and we jump back 20 years to the same living room where we see them watch *another* Patriots game.

It’s lazy screenwriting like this that really confuses aspiring screenwriters because they’ve been told that their first act has to move like lightning. This first act moves like a sloth whose feet are coated with molasses.

I bring this up to remind aspiring screenwriters that today’s writers are only allowed to do this because they’ve already gotten paid. They are developing the script for a studio. So they don’t have to worry about winning over readers. You, on the other hand, have to come up with a WAAAAAY more interesting opening than this script. I can promise you that.

And I’m not excusing these writers. Because even if you are getting paid, you still owe it to yourselves to try. You should still attempt to entertain the reader in that opening act, and not just inundate them with information.

And I got news for you. Quippy dialogue isn’t enough. It helps. But little funny quips like, “Make sure you packed your prune juice” (my line, not theirs) aren’t enough to entertain the reader through fifteen pages of exposition. Funny dialogue should SUPPLEMENT the scene. Not be the only thing it has going for it.

Did anything in the script work?

Well, as I’ve said many times before, I like when scripts take advantage of their concept. Especially comedies. Give us comedic scenarios that can only occur in your screenplay. 80 for Brady has a few of those.

One of them was when the girls first went on their trip. They had to pick up Carol, the one “80” living at an old person’s home. And they get there only to find out she’s sleeping. The problem is, this home takes sleeping VERY SERIOUSLY. They NEVER wake their members up. So the girls have to sneak into this place, wake up Carol, and kidnap her.

It’s a lighthearted scene. It’s not anything special. But it was unique to the premise, which I liked.

Another one was the ending when the Patriots went down 25-0 and Lily sneaks up into the Offensive Coordinator’s booth, takes the coordinator’s microphone so she can give Brady a pep talk (which nicely connects with her own battle). I think most writers would’ve clumsily written some scene where the girls corner Tom Brady and try to hang out with him or something (it looks like they may have done exactly this in the rewrites). This was a more elegant connection between them and Brady. Dare I say it was perfect!

But these moments aren’t enough to overcome a standardly executed script with an extremely lazy first act. So, unfortunately, it wasn’t for me.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Scripts work better with specificity. It’s always better than generality. So when the women first eat at a restaurant in Houston, the slugline says, “INT. FANCY RESTAURANT.” Come on, guys. It took me 3 seconds to google ‘best restaurants in Houston.’ “Brennan’s” came up. So there you go. “INT. BRENNAN’S RESTAURANT – NIGHT.” If you’re worried the reader won’t know it’s fancy, tell them it’s fancy in the first line of description underneath the slug!

What I learned 2: Pay attention to how this film does. Cause if it does well, you may see a new trend emerge – theatrical releases for former star actors and actresses 60 and up. Which means you can start writing specs for those actors.