The new newsletter is in your inboxes. In it, I set up your screenplay gameplan for 2023, telling you the exact steps you need to take to achieve success. I also set up the LOGLINE SHOWDOWN, a new Scriptshadow feature of 2023 that’s going to be a blast. I review the original draft of a cult classic screenplay that is said to have been GENIUS before the film’s embattled director screwed it up. I also review a trailer of the coolest high concept script idea I’ve seen all year. How come nobody here came up with it??? HAPPY NEW YEAR!

If you want to get on the newsletter, e-mail me at carsonreeves1@gmail.com!

“I know we just won the World Cup. But what we really want to know is what are Carson’s Top 10 movies of the year???”

“I know we just won the World Cup. But what we really want to know is what are Carson’s Top 10 movies of the year???”

It’s the final post of the year!

Yes, after this, I will be heading deep into the Scriptshadow caves to plot the ongoing goings-ons of 2023.

But before we get there, we must give 2022 its last dab by celebrating the best movies of the year (you can see my ‘worst movies of the year’ list here). It’s been a transitory year for the industry. Studios seem to be confused about what the masses actually want. And the indie outfits are watching helplessly as their films start their runs in hospice care. Justice for storytelling.

Despite this, there were some really good movies in 2022, even if Quentin Tarantino called it the worst decade of movies in history. Some notables that didn’t make today’s list include Deadstream, Smile, Emily the Criminal, Cha Cha Real Smooth, and X. Movies that I still haven’t seen yet include The Woman King, The Banshees of Inishirin, The Menu, The Fablemans, Aftersun, Knives Out 2, Babylon, and The Whale, most of which I’ll catch soon.

This is one of the most offbeat Top 10s I can remember putting together. The movies really run the gamut. Prepare yourselves… for the best films of 2022!

10 – Triangle of Sadness – I struggled long and hard about whether to put this movie into my top 10 or Emily The Criminal. In the end, I chose this because it’s so unlike any movie you’ll see this year. The “triangle of sadness,” by the way, refers to a term in the modeling industry regarding the three points between your eyes and nose. When they’re too scrunched up, it makes you look sad. Triangle of Sadness doesn’t do as good of a job as The White Lotus at satirizing rich people. But it has some gonzo scenes, such as the drawn-out 12 minute argument between two models about whether a woman should ever pay for dinner. There’s a lack of connectivity to the narrative that’s frustrating at times (we’re all of a sudden on a yacht yet no one tells us how we got there). It’s probably going to piss you off occasionally but the movie is guaranteed to stay with you. It’s worth checking out.

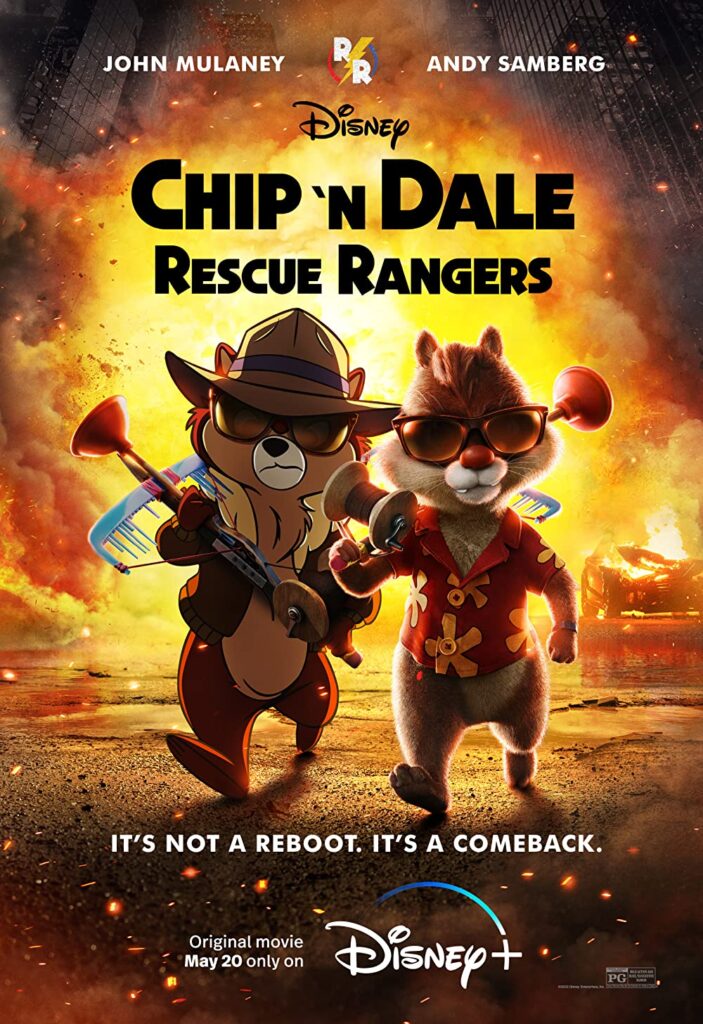

9 – Chip and Dale Rescue Rangers – Natural transition, right? One of the artiest movies of the year to an animated studio film! But don’t be fooled by Chip and Dale’s shiny exterior. This is the best deconstruction of an animated film, maybe, ever. It’s like Who Framed Roger Rabbit on steroids. And if you have any doubts about what I’m pitching here, this film comes from the Lonely Island crew – Andy Samberg and Akiva Schaffer. Those guys aren’t going to sign on to an animated film unless they can do something different with it. And that they do! One of those wonderful surprises where you turn it on, expecting to give up after five minutes, only to watch the entire thing.

8 – The Night House – If you’re like me, a red-blooded human being, you love Rebecca Hall. I recently watched Vicky Cristina Barcelona again for my dialogue book and Hall is excellent in it. Her only weakness is that she often plays the same character. But that doesn’t hurt this movie. The Night House follows a woman whose husband mysteriously committed suicide and she visits the old summer house they owned and starts to receive messages from the other side. Her dead husband seems to be trying to tell her something. And when she starts looking into his life, she discovers there are things about him that she never knew. This is “headier” than your average ghost movie. So it’s not for the “Smile” crowd. But if you like genre stuff that’s more adult-themed, this fits the bill.

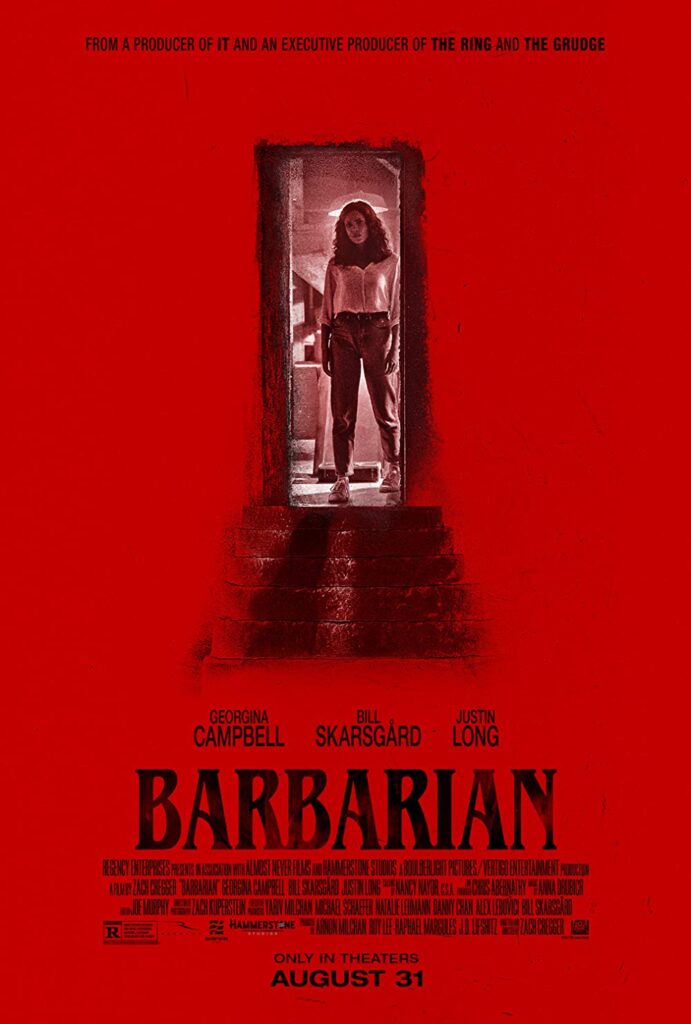

7 – Barbarian – When I reviewed this, I said it had the best first act of the year. I stand by that. The first act is amazing. So much so that it’s disappointing the rest of the film doesn’t live up to it. But there’s something to be said about a film that is determined to get crazier and crazier as it goes on. I mean where else are you going to find a 6 foot 5 inch naked beast woman running around deserted Detroit suburbia killing anything she can find? I also love Justin Long leaning into his despicableness. Who doesn’t want to watch (spoiler) Justin Long suffer an agonizing death? Biggest WTF movie of the year. Constantly keeps you guessing.

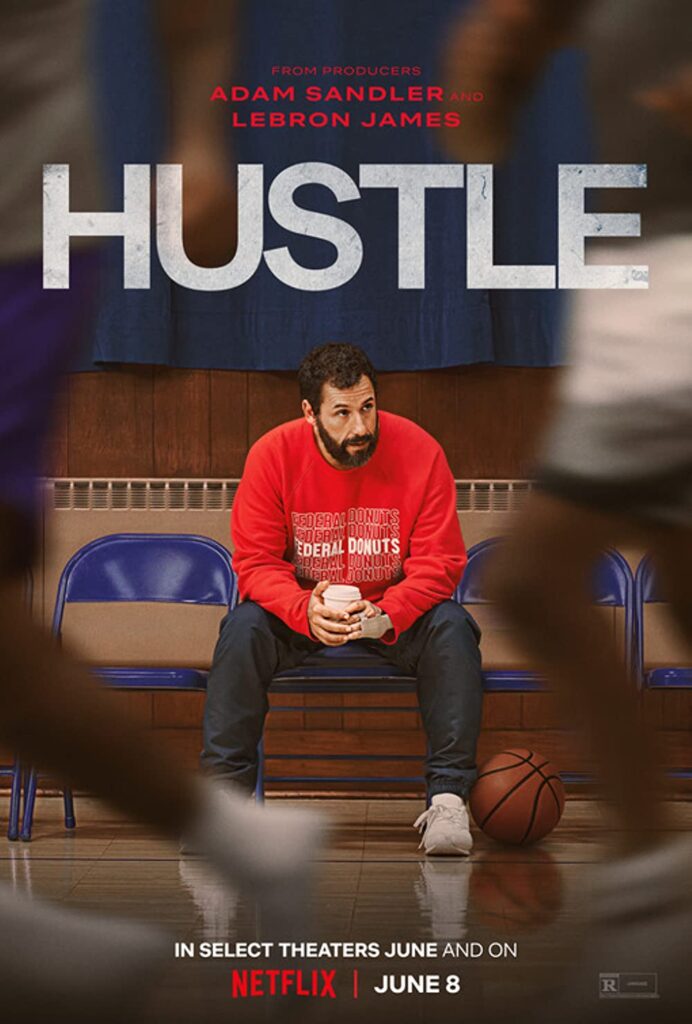

6 – Hustle – How good is Adam Sandler when he tries? This is a huge part of the reason why Sandler has such a heated hater fanbase. It’s because we all know how awesome he can be when he puts in the effort. And this is the perfect role for him. Washed up, overlooked coach who puts everything on the line for some no-name basketball prospect from another country. I didn’t think you could do traditional sports movies anymore. The genre is too cliched. But you’ll note that one of the ways Hustle avoided getting too cliche was it didn’t have “the big game.” The climax, instead, is a workout. That alone made this feel different. But the real pillars of this film are Sandler and the guy who plays the recruit. It’s like a double-dose of underdog. I love films that make you feel good afterwards. This achieved that more than any other film on the list except my number one film.

5 – Avatar: The Way of Water – It’s been a week now since I saw the film, allowing me some perspective. My feelings remain the same. The film needed a main character. Jake Sulley was clearly the main character in Avatar 1. Who knows who the main character is here. The reason that matters is that the audience feels emotionally detached from a film in which they don’t have a guide. That really hurts the film. On the flip side, I’ve never been to another planet in any movie that’s felt this real. It’s weird because, on the character front, Cameron makes a mistake that keeps you at a distance. But on the technical front, he creates a world that feels as real as the one you’re living on. It all adds up to a strong movie that leaves the slightest bad taste in your mouth because you were hoping it would achieve ‘great’ status.

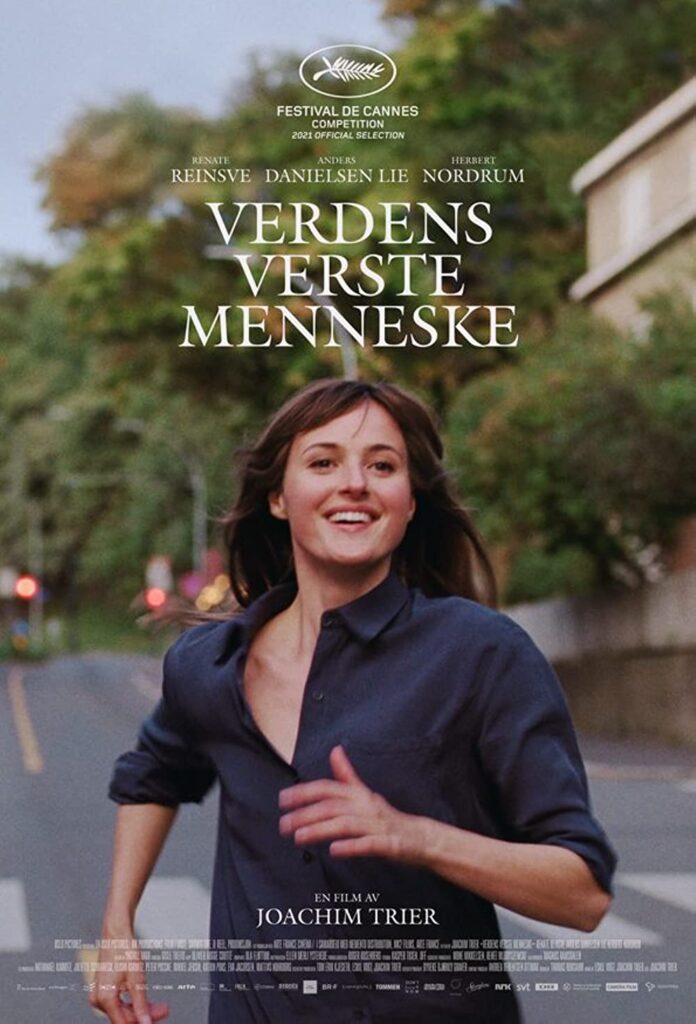

4 – The Worst Person in the World – What’s funny about this tiny Norwegian film is that it has something in common with Avatar 2, which is that I felt like I was in Oslo as I was watching the film. You wouldn’t think I would like a film like this. There seems to be nothing in the way of a plot. The main character is wishy-washy. But one thing film can do that screenwriting cannot is take you somewhere. And if you like that somewhere – and the director does a great job of enhancing it with cinematography and score – you’ll overlook a lot of story problems. Something about this movie and the way it covered a lost soul spoke to me in a way I can’t quite articulate. I just know that when I watched the film, it stirred something up. And isn’t that what it’s all about?

3 – Thirteen Lives – By far, the most underrated movie of the year. I hear no one talking about it. I don’t know if that’s because it was released by Amazon or what. This film had so much for going it, the most shocking of which was that Ron Howard left his schmaltzy storytelling crutch behind and, for once, let the truth be the focus. Maybe that’s why it didn’t resonate more. It was too realistic for people. But I’ll never forget the way these divers came up with this impossible solution for saving the kids, accepting the fact that there were going to have to kill some of them, but did the rescue anyway because it was better than leaving them all to die. I think the best movies put the characters in such a perilous situation that the audience wonders what they would do if they were in that position. And that’s where my head was at this whole movie. What would I do if I was one of those divers? Because there wasn’t a single simple solution to the rescue.

2 – Everything Everywhere All At Once – I saw somebody trashing this movie in the comments section yesterday. And I don’t begrudge them. The movie is so weird and makes so many odd choices, that there’s no way it doesn’t alienate some people. I mean, at one point, there’s a three minute scene with two rocks talking to each other. No matter how good your movie is, not everyone’s going to be on board with that. I tell you guys all the time that I like writers who take risks. But when push comes to shove, we’re all too afraid to truly take risks. We always revert back to the safety of our traditional choices. The Daniels are the only people in Hollywood making legitimately crazy choices and seeing where they take the story. And I think what makes it work is that, in the end, they have a traditional approach to character development. They give their characters flaws – like the mother giving up on her family – and then they arc that character over the course of the story. That dedication to character is what holds these wild choices together. This movie made nearly 70 million dollars at the box office which is insane. It’s the kind of arthouse fair that would normally make 10 million if it was lucky. Goes to show what an amazing job the Daniels did. I expect this film to be the belle of the Oscar ball.

1 – Top Gun: Maverick – How bout this? The director of my least favorite movie of the year, Joseph Kosinski, is also the director of my favorite movie of the year. If that isn’t proof that nobody knows anything, I don’t know what is. Top Gun 2 is bigger than just one movie. Not only did it make everybody feel good at a time when we all desperately needed to feel good. It was a reminder to Hollywood to lighten up. All my friends who never go to the movies saw Top Gun 2 so I asked them, why did you see this film over all the other movies that came out this year? And they said, “Cause it looked fun and it looked light.” When I pressed them on it, they said that movies out there are all too serious these days. They pointed to Black Panther and Eternals. These are Marvel films that people are complaining are too serious! If there’s a lesson to Top Gun, it’s to start making movies again that bring everybody together rather divide them. How crazy is it that a Top Gun film became the most important movie of the year? Joseph Kosinski recently stated, “There were a million ways this movie could’ve gone wrong and one tiny way it could go right.” It’s safe to say he found the right way.

SCRIPT CONSULTATION DISCOUNT 150! – I’ve got a couple of screenplay consultation slots open for the end of 2022. If you’re interested, e-mail me with the subject line, “CHRISTMAS 150,” and I’ll take $150 off my regular rate. If you’re never had notes from a professional before, I would strongly recommend taking this opportunity to do so. I can help you identify and fix things in your writing that would otherwise take you years to learn on your own. Not to mention, elevate your current script. So if you want to get a consult, e-mail me at carsonreeves1@gmail.com. I do features, pilots, first acts, short films, loglines, whatever you need me for!

MERRY CHRISTMAS, EVERYBODY!

Over time, I’ve gotten better at knowing what movies I’m going to hate ahead of time and, therefore, not go to them. I knew to steer clear, for instance, of the “M” movies this year: Marry Me, Morbius, and Moonfall. Or flicks that had ‘disaster’ written all over them from the start – Amsterdam and Bros.

There was a time in my life, however, where I was susceptible to indie hype. The indie film world had this amazing marketing gig going whereby they insisted that whatever the latest indie film was, it was the greatest film in the world. And I bought into it every time. Despite stumbling out of 90% of the films looking like a lost turtle.

Apparently, my bad movie radar has not been perfected yet because, as you can see, I still carved out 20 hours of my life to watch these duds. Let me know what you think of my picks and, of course, share you own Worst 10 in the comments sections. I’m curious to see what you guys disliked.

10 – A Christmas Story Christmas – As someone who religiously studies screenwriting, one of the things that frustrates me to no end is when a writer does everything technically right and, still, the result is flat. A Christmas Story Christmas should not have been as boring as it was. It’s a fun take on a sequel. The original film showed the quirkiness of Christmas through the eyes of a child. The sequel showed it through the eyes of a father. The script does everything in its power to create a main character who’s struggling in life and who has a fatal flaw he must overcome. Just like the original film, we have a wacky cast of characters meant to keep the story continuously entertaining. And yet it all lands with a giant thud. I suspect, like most scripts that never get off the ground, the problem started with the main character, specifically that seeing a holiday through the eyes of an uncynical child is a lot more entertaining than seeing it through the eyes of a cynical adult. I’m not sure the movie ever overcame this handicap. A lot of screenwriters are making this mistake recently. They’ve been handed these older legacy characters and try to make them the hero in a movie that, traditionally, would not have them as the hero. One of the most lifeless movies of 2022.

9 – The Adam Project – I debated whether to put this one on the list. There is passion in the way this movie is put together. Ryan Reynolds truly wanted to make a Back to the Future for this generation. But the screenplay makes a classic Scriptshadow mistake, throwing everything and the kitchen sink at the story, and, as a result, creating a movie that’s all over the place. I’m not even sure who the main character is. Is it young Ryan Reynolds? Is it old Ryan Reynolds? The movie definitely suffers from an inability to understand whose eyes we’re supposed to be experiencing the adventure through. Can you imagine Back to the Future if it was unclear whether Marty or Doc was the main character? And Adam’s problems don’t stop there. There’s a ton of weird time-travel nonsense going on, which only gets in the way of a story that’s already got a lot to keep track of. A writer needed to come in and streamline the heck out of this thing.

8 – The Bubble – Say what you will about Judd Apatow. He was the last guy in America to consistently pump out feature comedy films that brought masses to the theaters. Since him, comedy has descended onto streaming channels. The Bubble proved one valuable piece of info to me – which is that nobody wants to watch movies about Covid ever again. Bo Burnham’s Covid film was great. And that was about it when it comes to good Covid films. This topic brings back feelings of depression and anger, with everything that went on during those two years. Who wants to experience that again? Not me. With that said, this movie did start to find its groove toward the last 45 minutes of the film where the characters legit started going crazy. Apatow seemed to finally figure out what his movie was about. But it was too late.

7 – Thor: Love and Thunder – The badness of this film hits me once in the gut and once in the face. Because, before this movie came out, I thought director Taika Waititi was going to be the savior of Star Wars. But this movie was so bad – and it only gets worse in your memory – that I’ve lost a considerable amount of faith in Taika. The film continues to perpetuate the Mary Sue myth, turning Natalie Portman into a God cause, um, cause women kicking butt is the number one priority for Hollywood films in 2022? The film also felt considerably low-stakes. Its biggest sin, however, is wasting a great performance by Christian Bale. This might’ve gone down as an all-time performance had the film not been so bad. This script also taught me that comedy needs boundaries. It can’t be “anything goes.”

6 – Nope – Yep. Whether you want to admit or not, Peele wrote and directed an awful movie. The number of flaws in this story is endless. The third act alone has more “wait a minute, what?” and “WTF” moments than a 1983 Saturday morning cartoon episode. The more I look back at this film, and knowing what I know about Peele through the interviews he gave, the more convinced I am that he spent an entire year high as f—, writing and directing this movie. It’s the only thing that makes sense considering how sloppy it all is. The movie’s climactic moment is a desperate attempt to photograph an alien ship with a fake amusement park water well camera, despite the fact that the alien ship is going to crash into the ground any second and be accessible for the whole world to see and take pictures of. Oh wait, the alien ship can’t be filmed on a digital phone (/eyeroll). Only physical film. Cause, um, yeah, those are the rules. What even was this movie??? A complete and utter clustrf—k of ideas conceived during copious amounts of weed-smoking. If you want to go smoke weed and make wacky short films with your buddies that you post on Youtube, like Donald Glover used to do, great. I’m all for it. But if you’re asking us to pay 20 bucks to see your film, do us the dignity of sobering up and thinking through your narrative and your rules so that the story you put on paper actually makes sense.

5 – Dr. Strange and the Multiverse of Madness – As soon as they introduced the random Latina superhero sidekick who had absolutely zero chemistry with Dr. Strange, I knew this movie was doomed. But somehow it doomed itself even more, turning an alternate version of its main character into a zombie, despite the fact that nothing at all in the rest of the movie was equipped to handle a zombie character. But the biggest issue of all was that the movie squandered a fun idea. You’re on a road trip between multiple universes. You could’ve had so much fun creating all these different worlds. And yet that part of the script was relegated to a tiny 10 minute section. It was bizarre. One of the messiest movies I saw this decade. And that category is quite crowded these days.

4 – Matrix Resurrections – In retrospect, I know why this movie was so bad. Lana Wachowski said that, as they were shooting the film and Covid hit, she considered it a blessing in disguise because it meant she didn’t have to finish the film. Reading the subtext of several other interviews she gave, Lana seems to have been bullied into making the sequel. It was not something that was high on her priority list. It goes to show how important pure unadulterated passion is to writing and making movies. Screenplays and films are not forgiving mediums if you’re only kind of into what you’re doing. You have to be beyond passionate. Which is why Avatar 2 is such an experience. That is a movie made by someone obsessed with making that movie. Resurrections started out okay. It had some interesting ideas. But just like anything that you’re not giving 100% to, it eventually falls apart. There’s this moment midway through the film where a big fight is taking place and one of the characters from the former films, the Merovingian, is randomly screaming out obscenities, and you’re just sitting there wondering, “What is happening right now?” It’s so bad.

3 – Licorice Pizza – I know this was technically released last year but I watched it this year. I apologize to all of the Paul Thomas Anderson lovers out there. But I seriously question whether the modern day version of this man has any talent at all. His last good movie was There Will Be Blood. What has he done since? The Master, which was average at best. The Phantom Thread, which managed to be so uninspired that, despite having the greatest living actor in the world in it, no one watched it. Inherent Vice, whatever the heck that was. And now this movie. Which is so nonsensical and so devoid of a clear narrative, that you almost think Anderson is playing a joke on you. I kid you not, one of the plot developments is our high school main character opening a mattress store. That’s not a misprint. That actually happens. Literally, nothing in this movie makes sense. It’s so agonizingly bad. I will say, however, that, Alana Haim’s performance was good. I hope to see her in more films. And the main kid is a good actor as well. But there’s no story here for them to work with. At least not one that makes any sense. I say this with complete conviction – if this script appeared on Amateur Showdown, it would finish with the least amount of votes.

2 – Deep Water – For as confusing and untethered as Licorice Pizza was, it doesn’t hold a candle to how dumb, clunky, and amateurish Deep Water is. It’s movies like this that make me wonder if anyone in Hollywood knows anything. Here you have Ben Affleck, who is considered one of the smarter actors in Hollywood. He’s also on the A-List. So he gets sent the best of the best material. And he chose to make this movie?? If you have Hulu, I want you to go watch the first 20 minutes of this film and report back to me on whether you have any idea what’s going on. Cause I sure didn’t. And if you can manage to be that confusing in the opening of your film, you have a special kind of talent for being awful. There isn’t a single story beat that makes sense in these first 20 minutes. How did anybody allow this movie to happen???

1 – Spiderhead – I said it at the time. Spiderhead is an example of the worst thing about Hollywood. Which is that the industry is more interested in getting movies made than making good movies. To a certain extent, I understand this. It’s so hard to get films made that, if you have something that can get made, despite its low quality, someone will make it, because nobody wants to leave free money on the table. But boy is Spiderhead a cautionary tale on what happens if you let that philosophy guide you. Reese and Whernick were hot writers. They’re shepherding the Deadpool franchise. They had an old dusty script in their drawer. It was terrible but their agency and the studios knew they could get it made with their names on it. So they put the package together and made the thing without ever asking why anyone would want to a make a movie where not a single scene in the screenplay makes sense. I mean, this is a movie about a corporation forcing tests on its patients where the patients can just waltz up to the control room any time they want. I’m sorry but if those are the rules of your story, you’re not writing a movie. You’re writing garbage. Everything from the concept to the mythology to the timeline that was chosen to tell the story in ensured that you left this movie enraged that you wasted two hours of your life. This movie is the epitome of awful.

Tomorrow, I share my 10 favorite movies of the year. And a couple of them are going to surprise you!

Is the Screenwriting Grinch finally ready to smile? Do we have a Christmas script worth reading??

Genre: True Story

Premise: In the aftermath of WWII, a traumatized Frank Capra and Jimmy Stewart use the making of IT’S A WONDERFUL LIFE to attempt to find a way back into normalcy.

About: I promised myself I wouldn’t start reviewing Black List scripts until the new year. However, I couldn’t help myself when I saw a script celebrating my favorite Christmas movie, It’s a Wonderful Life. It felt quite festive to read such a script, which finished with 9 votes on the list.

Writer: Alexandra Tran

Details: 104 pages

A big reason I continue to be fascinated by It’s a Wonderful Life is that its inciting incident occurs in the third act. It’s just so antithetical to what we’ve been taught “works,” and yet even though the movie brazenly rejects this accepted premise, it thrives.

It makes me question everything. If a movie that rejects one of the most popular screenwriting rules in the world – your inciting incident should happen by page 15 – and can still become not just good, but one of the greatest films of all time, do rules even matter?

Ponder that while I summarize the plot.

World War 2 has just ended. Mega-director Frank Capra has spent the last three years making promotional movies for the military to keep recruitment up. So when the war abruptly ends, he has to decide what his first post-WW2 movie is going to be.

Meanwhile, legendary actor James Stewart has just come back from his service in the Air Force. He’s in a really weird headspace. Before the war, he thought acting was everything. Now, it seems trivial. So Stewart wants to move back to the Midwest and live a normal life, quitting acting forever.

That is until Capra shows up at his door and says I want to make this movie about a guy who dies and realizes what the world would look like without him. It’s ultimately a feel-good movie that no studio wants to make. They all want to make war movies instead.

At first, Stewart turns him down. But after speaking to his new girlfriend, Gloria, he decides to give it a shot. Right away, it feels like the wrong decision. Stewart can’t find his acting mojo. At one point, during one of the scenes, Stewart’s acting is so bad that one of the crew members laughs.

It’ll be up to Capra to shake Stewart out of his malaise and get a good performance out of him. Except the deeper into the shoot they go, the less likely that becomes. Will Stewart finally find his acting chops again? And will Capra’s big non-war-film gamble pay off? Maybe not right away. But something tells me it’s going to do well in the long run.

If It’s a Wonderful Life is a white Christmas, It’s A Wonderful Story is more like a light Christmas flurry.

There’s a major lesson that every screenwriter can learn here. Which is how important the introduction of characters is to your screenplay. Because I would argue that the bulk of this screenplay’s problems boil down to missed opportunities regarding the way the two main characters were introduced.

It’s a Wonderful Story wants to paint each of its two heroes in a particular way. For Frank, it wants to portray him as someone desperate to bring heart back to the cinema during a time when the movie industry just wants to make war movies.

For James, it wants to portray him as an actor who’s lost his way, who doesn’t see acting as important anymore after having experienced the horrors of war.

Here is the problem, though. Frank’s introductory scene has him gung-ho about cutting these promotional war films. He’s the guy responsible for charging young men up and making them want to go fight for their country. And he’s super into it. When a character comes into his editing session and tells him to stop, Frank is defiant. He wants to keep going. This is what he does.

So to then tell us, out of nowhere, that Frank is disgusted by those movies and that what he really wants to do is make a heartfelt movie, is confusing. Film is a show don’t tell medium. You just SHOWED us that he liked making those promotional films. So why does he hate them all of a sudden? It doesn’t make sense and it makes the character unconvincing throughout the rest of the script.

I know why the scene was written – and actually this is one of the harder things about screenwriting. The writer wanted to establish what Frank did during the war. Which is good. You want the audience to have that information. But screenwriting requires that you be able to do multiple things at once. Establishing information about a character is only one of several things you need to do within a scene. What wasn’t added was Frank’s resistance to war filmmaking and his pining to bring happiness and heart back to theaters.

With James Stewart, his whole thing is that war has changed him. It’s made everything else in life unimportant by comparison – especially acting. And that’s a noble character arc to examine. However, you never showed us James Stewart fighting the war. You never showed us him experiencing the horrors of war.

Let me repeat this because it’s important. Movies are a show don’t tell medium. You needed to show us James Stewart in the war seeing his friends die, almost dying himself, being scared out of his mind. THEN! When he’s ding-batting about trying to deliver a silly line of dialogue on a movie set, we understand why he thinks it’s stupid. Cause we saw, with our own eyes, him doing way more important things.

In many ways, a screenplay is a like a house of cards. If you screw up a few of the key pillars, the whole thing can come crumbling down. But you should find it helpful to know that most of those pillars are in your first act. So pay attention to them – moments like your main characters’ introductions – in order to make sure those pillars are strong.

These pillars were not strong and it kept coming back to haunt the screenplay again and again.

On top of this, I’m not really sure what this script is about. What is it we’re trying to say here? When you write period pieces, there’s more of an expectation from the audience that there be a lesson learned. If you look at a movie like The King’s Speech, that story was about placing the collective good above your own personal fears. He didn’t want to give the speech. He was terrified of it. But, in the end, he faced those fears because he knew it was important for the greater good of the country.

I don’t know why we’re revisiting this movie. What is important about it? I thought the script was going to do something clever like cover the production of It’s a Wonderful Life in a way that semi-mirrored the actual film. For example, what if James Stewart was feeling similar things about his own existence in relation to the fictional character he played? What does this world look like if James Stewart was never born? Fun stuff like that.

But it’s more of this traditional biopic “This is how it went down,” – main characters have their Screenwriting 101 fatal flaws they need to overcome. Nothing is natural or engaging. It’s a script that would do well in a UCLA screenwriting competition because it’s competently constructed.

But there’s no heartbeat to it. Which means Ebeneezer Carson strikes again! But all is not lost. Cause the script did remind me of what a great movie It’s A Wonderful Life is, and made me excited to watch it again this week.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Don’t ever allow your character to say something that isn’t consistent with who they are. In this script, Frank Capra is presented as this thoughtful, sweet, humble man. However, when a studio head tells him that he’s old and out of touch, Capra replies with, “I’m the most successful director in Hollywood.” Does that response sound thoughtful, sweet, or humble? No. So watch out for this. I’m guessing the writer wanted the reader to know that Capra was a highly successful director. But you can’t ever give information out in a way that betrays the character. Always always stay true to the character. There’s always another way to slip that piece of information in there (have another character bring it up, for example).

The most important movie to the long-term health of the movie business is finally here! Does it deliver??

Genre: Sci-Fi/Fantasy

Premise: Jake Sulley must relocate his family to a far away water tribe on Pandora in an effort to hide from the humans, who are determined to find and kill him.

About: Avatar 2 is finally here. From the time it was conceived til today, the entertainment landscape has changed drastically. Superstar director James Cameron has never had to deal with this particular box office landscape yet. So everyone’s holding their breath to see if his newest film can bring people to the theaters in droves, like the old days. The film started out slightly underperforming with 135 million. But we won’t know how this film is going to do until the numbers come back for next weekend. Cameron is famous for having movies that can play in theaters for months. If the hold is 25% or less, expect Avatar 2 to be a monster hit. If the drop is 40% or more, we’re probably only getting one more Avatar film. — Avatar 2 was conceived in a writer’s room with a group of writers (like television). Cameron had them all break the stories for 2, 3, 4, and 5 together. Only after they figured out the details of what was going to happen in each movie did he assign the writers to their respective sequels, as he wanted to make sure they were invested in the entire story arc before assigning them individual movies. Rick Jaffa and Amanda Silver (Rise of the Planet of the Apes) were assigned the first sequel, this movie.

Writers: James Cameron and Rick Jaffa & Amanda Silver

Details: 3 hours and 2 minutes (according to Cameron)

![]()

Whatever your opinion is on James Cameron, you gotta admire the guy’s chutzpah. A billion dollars of production costs all in. 800 pages of notes. Thirteen years. Five writers. Four sequels. Reinventing special effects. The guy doesn’t just want to make a movie. He wants to change the very experience one has while watching a movie. It’s amazing to watch and my admiration for him has only grown during these interviews he’s given to the lead-up of this film.

But you know the rule here at Scriptshadow. Doesn’t matter if I hate the story behind the movie or love it. It all comes down to one question: IS THE MOVIE ANY GOOD?

Is Avatar 2 any good?

Let’s find out.

It’s been about 15 years since we left Pandora. Jake Sulley is now a permanent Na’vi. He and Neytiri have a full family on their hands. And it’s a weird one. They’ve got two teenaged boys, Lo’ak and Neteyam. They’ve got a weird pre-teen girl, Kiri. They’ve got a young girl, Tuk. And they’ve got an adopted human son, Spider.

When a reborn Colonel Miles Quaritch, who’s been placed in a Na’vi body, arrives on Pandora, his sole mission is to destroy the leader of the Pandora resistance, his old nemesis, Jake Sulley. After he locates Jake, Jake and Neytiri decide to take their family and hide out on the other side of the planet, with a tribe of water aliens called the Metkayina.

![]()

Once there, the family learns the ways of the Metkayina, mainly how to live within and around water. The majority of this section belongs to Lo’Ak, who has a series of spats with the local teenagers, turning him into a bit of a lone wolf. He eventually finds friendship with a mysterious beat-up whale creature named Payakan.

Kiri seems to love her new surroundings although she’s such an oddball that she’s often caught staring into the horizon. But you get the sense that, in future movies, she’s going to become a bigger deal, because she has an almost superhuman ability to connect with the planet, which gives her extreme control over her surroundings.

When the kids are finally caught by Quaritch, he uses them as bait to lure Jake and Neytiri to his giant battleship. The Metkayina agree to help Jake, and it’s another Na’vi versus humans showdown. What follows is one of the greatest action sequences ever put to film, one that rivals the ending of Return of the Jedi. But do Jake and Neytiri rescue all their children? Or is the military too strong this time around?

![]()

Years ago, when HD televisions first started showing up at TV stores, the makers of these TVs had a phenomenal promotional stunt. They floated this story whereby someone came in to look at the first HD TV in action, and was so thrown by how clear it was, that he vomited on the spot. He wasn’t prepared for that level of realism.

This was back in the day where you could just make things up and nobody would fact-check you so, no doubt, this was a made-up story. At least, that’s what I thought until Friday, when I saw Avatar 2.

I watched the movie in IMAX 3-D over at the Grove and within the first two minutes, I considered leaving the theater because the 3-D and the level of clarity and the 48 fps (which makes the image look super-smooth) was such a potent combination that I initially couldn’t handle it. I literally felt like I was going to throw up.

Luckily, I got used to it. But there was a fork in the road moment there where I was at risk of missing a movie that I’ve been waiting 13 years to see. Needless to say, Avatar 2 is unlike any movie you’re ever going to see in your life. It’s its own thing. And when people talk about it being more of an experience rather than a movie, I don’t begrudge them that assessment.

I think what surprised me about Avatar 2 was that it was kind of a soft reboot of Avatar 1. Just like we had this character who’s been thrown into this new world and he has to learn about the world before dealing with the military threat late, now we have this entire family who’s thrown into this new world which they must learn about before dealing with the military threat late.

Your final opinion on Avatar 2 is probably going to come down to whether you enjoy that “learning about” section of the story. Because it’s the entire second act and it’s, mostly, conflict-free. It’s more about experiencing what living this “water-focused” tribal life is like. In that sense, it mimics real life for anyone who’s ever had to move somewhere new. You’re thrown into this uncertainty but you gradually figure out how to exist in your new environment.

I thought all of that was good. I do, however, wish there had been more conflict in this section. Because if you’re going to have a 90 minute middle act, it’s hard to keep an audience engaged for that long by only showing them your characters learning about their world. Audiences need more. There’s no doubt Avatar 2 lost some story momentum in that section.

With that said, there were several cool subplots in the second act that kept things afloat, the most successful of which was Payakan, the injured whale creature who befriends Lo’ak. You immediately fall in love with the gentleness of the creature and are devastated when you learn his history. I got so attached to this thing that I was ready to riot if he was killed. Honestly, I was going to walk out (for a second time!). The friendship between Payakan and Lo’ak almost made up for the lack of conflict in the second act all by itself.

![]()

Quaritch’s hunt for Jack Sulley was the one area of genuine conflict in the second act. This was actually a clever screenwriting move on Fox and Silver’spart. Whenever you place your characters in a safe area where conflict is light – you’ll sometimes see this in narratives where characters are in a witness protection situation – you want to intercut the bad guy getting closer and closer to finding them.

At least, that way, the audience gets the feeling that the safe habitat is only temporary. They know a reckoning is coming. And if an audience knows a reckoning is coming, they don’t care as much that the A-story is a slow burn.

Another way to stave off a slow burn is to give the audience a great show in the third act. And boy does Cameron deliver in that department. The third act battle is insane. I’ve never seen anything like it. When I made the grand declaration that Cameron was going to show Marvel what special effects could be when they’re not rushed – when they’re given the proper amount of care and attention – this is what I imagined.

There wasn’t a single muddy shot. Everything was clear. The geography of the action scenes was flawless. I was never once confused about where I was or what was going on, which happens constantly in Marvel films these days. And the level of creativity in the final action scene was light years ahead of all the Marvel stuff.

That moment where Payakan jumps onto the boat and flails around – wrecking everything, allowing the Na’vi to attack – was just so cool. That moment where they try and shoot a grenade-rocket at him he puts his head down, deflecting the grenade up and over to another part of the ship, which explodes. The battle felt so alive in a way I haven’t seen action set pieces feel alive in a long time.

It really was top-level stuff and it was confirmation that your money was well spent. Yes, the middle of the movie is a little slow. But that ending showdown completely makes up for it.

Despite the amazing experience I had going back to Pandora, Cameron made one critical mistake that kept this from being an “impressive.” Which is that he doesn’t have a main character in the movie. He doesn’t have an entry-point for the audience, someone we can latch onto and root for as our own avatar in this adventure.

![]()

Jake and Neytiri are sidelined in this movie, so much so that it actually shocked me. They don’t have much to do once we move to the water village. The story is more about the kids. And in Cameron’s technically correct choice to build up all the characters, he lost sight of the fact that we’re not sure who this movie is really about. Who has the most important journey? It’s not clear because of how spread out the focus is.

That really hurt the film, in my opinion, because after the final battle, when we start getting into the personal stuff, I found myself unclear on what the ultimate goal was here. And the reason for that is because we didn’t have a main character with a main goal.

It’s frustrating because there are some characters who come out of this fairly memorable. Spider comes to mind. Lo’ak to a certain degree. But I would argue that the character who’s the most memorable in the movie is Payakan, the whale. And as much as I loved that darned whale, I don’t think your best character in an Avatar movie can be a whale. It’s got to be one of the Na’vi or humans.

This issue pre-dates the movie because Jake Sulley and Neytiri were never standout characters, even in the first one. So the sequel kind of came in handicapped in that sense. But as a collective experience, it was still an amazing adventure. You can truly say that, if you watched Avatar 2 in 3-D, that you’ve never, in your life, seen anything like it. And that’s saying something.

[ ] What the hell did I just watch?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[xx] worth the price of admission

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: If you focus on everyone, you focus on no one. Movies are not TV shows. They need a clear main character. Heck, even TV shows need a main character. They’re just better equipped to spread the wealth. But movies need that one person we can latch onto so that we feel like we can navigate this large intimidating adventure. By jumping around to so many different characters, the audience was left with no one to truly connect with. And that, ultimately, prevented us from emotionally connecting with the film.