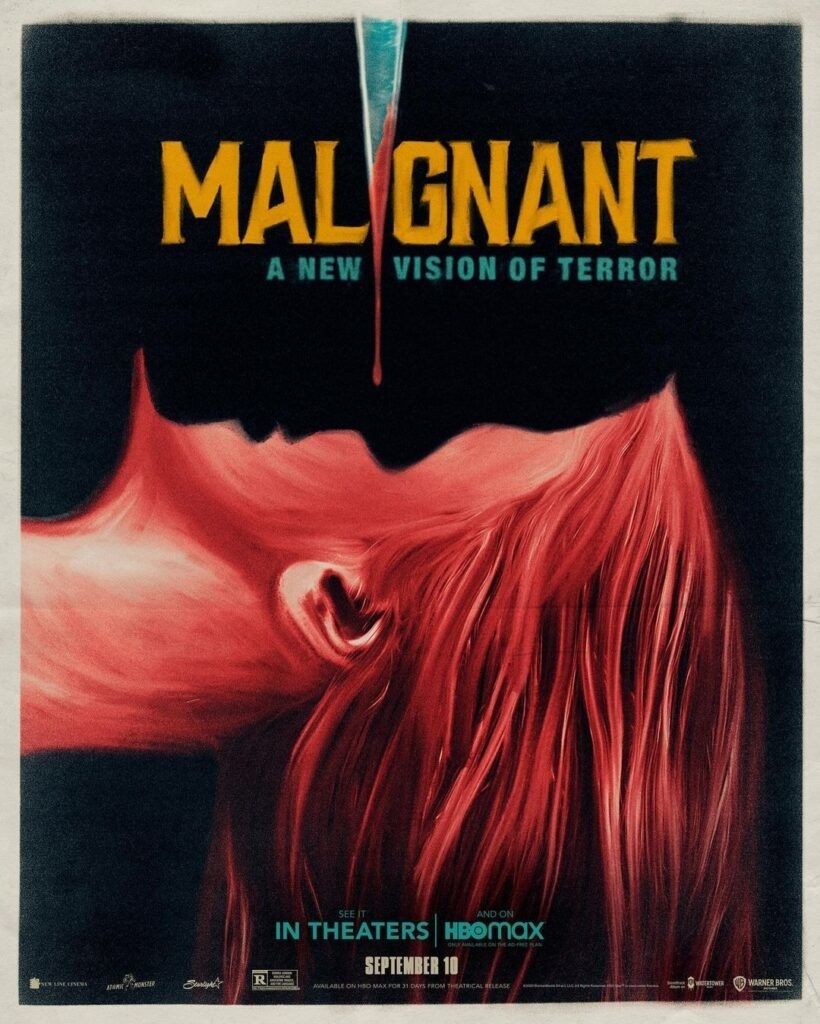

Today’s horror experience has me convinced there should be another Scriptshadow Showdown before the end of the year. Details coming soon!

Genre: Horror

Premise: After losing her baby, a young woman starts to have visions of a mysterious killer massacring his victims.

About: This one comes from James Wan, he of Aquaman fame. Wan is jetsetting back to his horror roots! Malignant only made 5.7 million at the box office this weekend but it’s tough to judge that number since it was available on HBO Max for free. Malignant also decided to keep its twist out of the marketing, which was a brave move, seeing as doing so would’ve, at the very least, doubled its revenue.

Writers: Story by James Wan and Ingrid Bisu. Script by Akela Cooper

Details: 110 minutes

When I pressed play on this movie, my first thought was, “Why the hell is James Wan going back to horror???” He’s directed Fast and Furious movies. He turned a so-so superhero into a billion dollar franchise. As much as I love horror, it is the stepping stone genre to bigger and brighter pastures. It didn’t make sense for someone this big to go back to it.

But after doing a little digging, I learned that James Wan’s wife came up with this idea. My assessment of the project immediately shifted upon hearing this news. Just to be clear, I don’t dislike when people in relationships work together. However, what I’ve learned is that it’s harder for a couple to see an idea clearly when they’re seeing it through the prism of, also, managing their relationship.

Two of the biggest movie stars in the world – Angelina Jolie and Brad Pitt – made a movie together and ten people saw it. Branjelina couldn’t see through their own relationship enough to recognize how boring their concept was.

For 90 minutes, while watching Malignant, I felt bad for James Wan. I figured his wife came to him with this idea. He wanted to make her happy so he agreed to direct it. He ends up having to release this unwatchable ridiculous horror movie… Good husband move. Bad artistic move.

But then something magical happens in Malignant. The twist arrives. And that twist is SO GOOD that it becomes the first twist in history to retroactively make the entire previous 90 minutes awesome.

In order to fully understand how this can be, you need to watch this movie. The film can’t be discussed without its twist. So I’m going to be discussing that here. You can read my review first. But you’re going to be robbing yourself of a really fun movie-watching experience.

The ridiculous plot of Malignant goes something like this. There’s this pregnant woman named Madison who was adopted as a child. She loses her baby when her abusive boyfriend beats her up. And now she’s trying to pick up the pieces in a creepy old house she moved into.

Meanwhile, a serial killer (or serial kidnapper) is out there killing and kidnapping people, then taking them back to his Hunchback of Notre Dame clock tower and stringing them up to the ceiling like a spider. I’m not kidding. This really happens.

From there, two of the cheesiest cops you’ve ever encountered in a movie try to find the killer. But they’re so bad at their jobs (not to mention talking to each other in a believable way) that they keep missing the killer. That is until Madison comes to them, with her sister in tow (who’s up for “Most Random Character of the Year”) and says Madison’s been having visions of the killer killing these people! The cops reluctantly bring her into the fold and start to get closer to finding the killer.

Meanwhile, Madison’s sister heads off to learn more about her adopted sister. She’s only recently found out Madison was adopted. This leads her to a psychiatric hospital and an old video tape of who her sister really is. And here, my friends, is where the big twist arrives. Spoilers ahead.

Have you ever heard about those people who have rare disfigurements where they have, like, some teeth and a nose partially growing out of their neck? Well, it turns out Madison had the most extreme version of this disfigurement. An entire second person was growing out of her back. And this disfigured thing had its own personality and everything.

So the hospital eventually had to cut the thing out. But, the only way they could do that was to shove the remainder of the thing’s face back into Madison’s skull. This “thing,” who calls himself “Gabriel,” has taken over her mind and is the actual serial killer. But it’s not just that. Since this thing grew out of her back, it’s learned to readjust Madison’s muscular-skeletal alignment and walk around backwards, resulting in some legitimately creepy offbeat physicality.

Madison finally recognizes that this thing has been taking over her body and fights back. But Gabriel isn’t letting the body go that easily. Only one of them will win out. Who will it be???

I don’t know how Malignant did it.

The second that image arrives on screen – where we see old footage of Madison, as a little girl, with this secondary monster thing growing out of her back – everything about the movie changed in an instant. It goes from stupid and nonsensical to “holy shit, holy shit, holy shit.” There’s this funny shot of the sister watching the video, horrified, that’s so over-acted, it’s ridiculous. And yet you’re reacting the exact same way she is.

But the genius of Malignant is that it doesn’t end with that shot. There are a lot of movie twists that don’t have legs. This one has ‘deadlift a thousand pounds’ legs. Because, while we’re watching this horrifying old video tape, we cut to Madison, who’s in jail with a bunch of women who are bullying her, and she turns around and opens up the back of her skull, allowing “Gabriel” to peek out, and she/Gabriel starts slaughtering everyone.

But not facing them. She kills them all backwards because Gabriel can only see out of the back of her head. This means that Madison’s bones need to twist and crack in a certain way so that they’re usable behind her. And that leads to an utterly unique fighting style that you’ve never seen before.

Why am I making a big deal out of this? Well, every horror movie these days either does the upside-down creepy crab-walk thing. Or they turn scary people backwards. But nobody ever comes up with a reason for why these people are backwards. It’s lazy writing.

The fact that these three figured out a way to not only have it make sense that the entity walked backwards, but then asked the question, how would something like this operate? And then built an entire backwards fighting style around it? – it was awesome. There’s no other word for it. I love when writers DO THE WORK and figure out why things are happening instead of throwing stuff onscreen with only a vague sense of how they work. They really thought about this character.

One of the creepiest images I’ve seen in a long time is when Gabriel takes over the body, Madison’s mind goes dead. So he’s running around, killing everyone, and, occasionally, we’ll spin around to see Madison’s face, which is in a dead stasis state. The fact that she’s doing these horrible things and is helplessly along for the ride was creepy as hell.

So how does it make the previous 90 minutes better?

Because once you realize how absurd this idea is, it allows you to not take everything so seriously. Any movie that ends with a functioning human tumor shouldn’t result in you getting mad because the cop character is boring. When you watch it a second time – which I plan to – you just laugh your ass off at the fact that this cop is such a tool.

Leading up to the movie, I kept hearing this word being bandied about – “bonkers.” Bonkers can either be a good thing or a bad thing. Sometimes people use the word for a movie that falls apart so spectacularly that they want to validate spending two hours on it so they say it was “BONKERS!” But Malignant really is bonkers. It’s so out there. It’s so weird. The movie is all over the place. I mean at one point they randomly show you that underneath the city is a second dead city that this city was built on top of. And then they just keep going on with the movie and never mention it again. It’s so silly and so stupid and so random. But I dare anyone to watch it and not be riveted by the third act.

The confusing thing is that so many of these horror movies start strong and fall apart. But this movie somehow does the opposite. And if there’s a preference between the two, that’s the one you want to use. You want start weak then finish with a bang. I mean, you want to do both, of course. But there’s nothing like the feeling of a movie that ends on a high. And WOW did this leave on a high. James Wan and his wife are geniuses!

[ ] What the hell did I just watch?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the stream

[x] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Where you place your big twist has a major effect on the third act. You can put it late in the third act, like The Sixth Sense does, and just allow people to finish on that adrenaline high. Or you can put it at the beginning of the third act and use the reveal to drive those last 25 minutes, like Malignant does. Once we learn she’s the killer and has this tumor thing controlling her, we watch her become this killing machine all the way up until the final scene. Every movie is different so you should assess this tip on a case-by-case basis, but I like the ‘beginning of the third act’ twist a lot because you get to stay with the twist (and play with the twist) longer.

Sci-Fi Showdown is only ONE WEEK AWAY!!! ENTRIES DUE NEXT THURSDAY!

Guys!

Do I need to remind you that NEXT THURSDAY is the DEADLINE for the Scriptshadow Sci-Fi Showdown? That’s when the five best sci-fi concepts submitted to me will be published here on the site, along with the scripts, and then you, the readers, will read and vote for your favorite screenplay. The winner will then get a review from me the following week. More importantly, if the script is good, we’re going to try and get it made! As in produced! So, if you’ve got a sci-fi script that you think is great, get it tuned up and send it to me by next Thursday.

What: Sci-fi Showdown

When: Entries due by Thursday, September 16th, 11:59 PM Pacific Time

How: Include title, genre, logline, Why We Should Read, and a PDF of your script

Where: carsonreeves3@gmail.com

I was trying to think of the most influential tip I could give you to dramatically improve your sci-fi script in one week, and I realized that if you can write one great sci-fi set piece scene, it can have a gigantic impact on how the script is received. That’s because a great set piece can be the motivator for why someone wants to produce your film. If they fall in love with just that one 10 minute scene, and have this vision of how awesome that scene is going to look in a movie theater, that could be the driving force that leads to a sale.

But before we can identify what makes a good sci-fi set piece, let’s talk about what makes a bad one. The worst set pieces are generic set pieces. A generic situation where people are shooting at each other. A generic car chase or motorcycle chase through a city. A generic fighting scene. There’s no form to these scenes. There’s no creativity to these scenes. They’re unimaginative time-wasters masquerading as entertainment.

The worst example of this is when you have one army on one side of the screen and another army on the other side of the screen and they race at each other, and in the trailer, they always cut away right before the two sides collide. That’s the epitome of a generic uncreative set piece. The reason I can say that with confidence is because nobody on this board can point to a single memorable moment in any of those scenes – Avengers Endgame, Ready Player One, Aquaman, Attack of the Clones – that occurs after the two sides begin fighting. It’s all a bunch of big boring generic nonsense.

These scenes don’t even play well on the big screen. But they play 100 times worse in an actual screenplay. Because we can’t see what’s going on. For these reasons, I want you to follow a simple formula to create a good sci-fi set piece (or any set piece for that matter)

1) GSU – The key character in the set piece should have a GOAL. If they’re not after something within the set-piece, nothing else will work. From there, you need the goal to be IMPORTANT. The stakes must be high. Everything’s going to feel a lot more important if the character is after a cube that has the power to destroy the universe than if they’re after a crispy chicken sandwich from Chick-fil-a. And, finally, add a time constraint (urgency). At the end of Star Wars, Luke doesn’t have all the time in the world to blow up the Death Star. There are mere seconds before the Death Star will have a clear shot at the planet Yavin. So Luke needs to destroy the Death Star NOW.

2) Based on your concept – This is a must for sci-fi. Figure out what’s unique about your concept and give us set pieces that COULD ONLY EXIST inside your movie. There are very few moments in the chase scenes from Mad Max Fury Road that felt like they could exist in another movie. Every aspect of the chase felt specific to the Mad Max universe. Check out Rossio’s recent “Timezone” spec sale to see another writer write set pieces that are specific to that concept. I would even say that Rossio is a master at that.

3) Contain your space – How you utilize space is the secret weapon for great set pieces. From the quickly condensing space in the Star Wars trash compactor scene to Captain America’s elevator fight in Winter Soldier to the first alien attack in James Cameron’s “Aliens.” A contained space provides structure. Whereas a big spread out area can be harder to manage and, therefore, get messy. The hardest thing about writing set pieces, in my opinion, is conveying to the reader what’s going on, because what’s going on can often spiral out of control. I mean, imagine writing what was going on in one of those giant Lord of the Rings fight sequences. Nine readers out of ten are not going to be able to keep up with the million and one things happening on screen. So utilize contained space where you can with set pieces. It can do wonders. It’s also a lot cheaper!

4) Imagination – Most writers don’t think that hard about their set pieces and, as a result, you get the same freaking set pieces you always get. I can’t stress this enough. Your set-pieces are your key selling point for a sci-fi movie. They’re where you get to show off what a great idea this is. So you really have to invest in them. Don’t stop until your top 3 set pieces feel like something we’ve never seen before. In the newsletter, we talked about the 5 million dollar spec sale for Deja Vu. A big selling point in that script was the car chase scene where the hero was chasing the bad guy but they were both in two different time periods. That’s an imaginative scene.

What’s a successful set piece that utilized most of these things? The Thor vs Hulk fight in Thor: Ragnarok. We have the contained space. We have the goal (fight to get out of here). The stakes (fighting for their lives). I’m not sure if there was a time constraint on that scene but it was so well constructed in every other area that it didn’t need one. It’s also a good example of how powerful a great set piece can be because that scene sold an entire movie. It was the centerpiece of every trailer. Which is a good thing to think about when writing your own set pieces: Would this scene be the centerpiece of a trailer? Could they sell the whole movie on it? When the answer is yes, that’s when you know you’re onto something.

Another one is the famous T-1000 truck chase sequence in Terminator 2. You may have never realized this until now but that was a classic SPATIALLY CONTAINED scene. The chase doesn’t happen out on a highway, like a boring Michael Bay chase scene. It happens in this contained space with these inescapable walls on either side. Which wasn’t just different, by the way. It added to the intensity of the scene because it gave the Terminator and John Connor no way out. It’s why it remains, to this day, one of the top 5 sci-fi set pieces of all time.

A lesser known set piece is the car-attack scene in Children of Men, which is contained in TWO WAYS. We’re cramped inside this car with five characters who are trying to escape. And then the car itself is contained by this tiny road in the forest. When they’re then ambushed and have to reverse out of the attack, there’s only one place to go. Backwards, up the very same road they came down. It works so well specifically because of how much Alfonso Cuarón focused on containing the set piece.

What I need you to do is spend the next three hours thinking up a big fun set piece THAT COULD ONLY HAPPEN IN YOUR MOVIE due to the fact that it’s so organically connected to your concept. And then apply as many of these above rules as you can. You might not be able to use all of them. But you should be able to get most of them in there. If you do it right, you’re not only going to come up with a great scene, you’re going to come up with a scene that SELLS why your movie should be made.

Good luck! ONE WEEK LEFT!!!

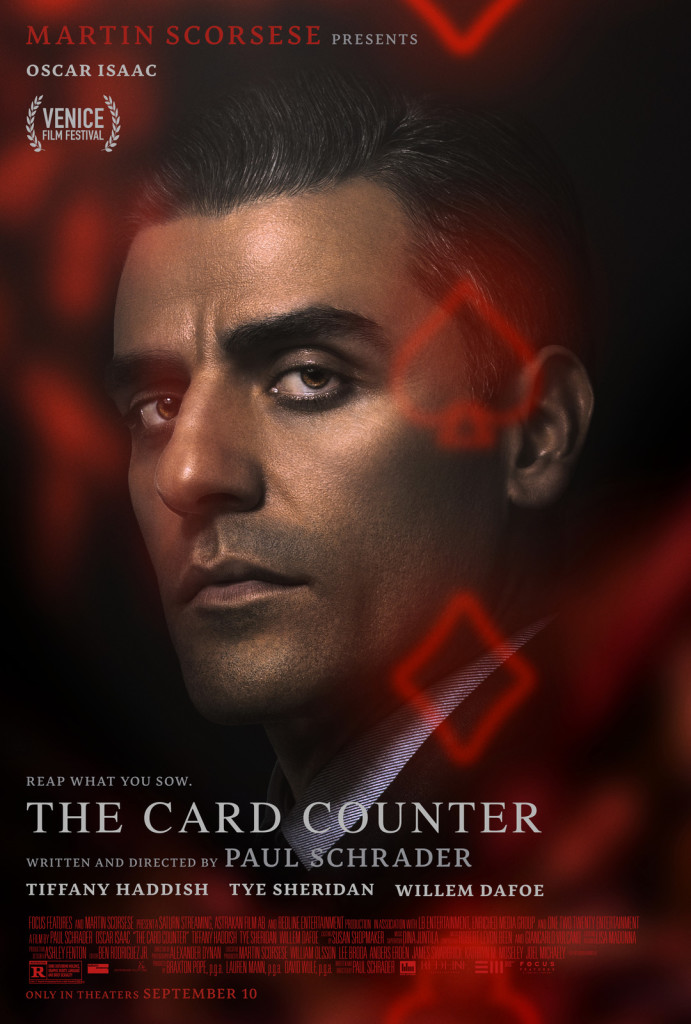

Genre: Drama

Premise: A low level blackjack card counter with a dark past makes a risky decision to get staked by a big investor in an attempt to make a lot of money.

About: This is the latest script from Paul Schrader, writer of Taxi Driver. The movie stars Oscar Isaac and has made a lot of fans on the ‘serious critic’ circuit, currently standing at 93% on Rotten Tomatoes.

Writer: Paul Schrader

Details: 94 pages

Readability: Fairly fast (very dialogue driven)

Paul Schrader is a hard writer to figure out. The reason everyone knows his name is because he wrote one of the biggest films of the 70s, Taxi Driver. And, yet, if you asked anyone why they liked the movie, they would inevitably tell you it was because of the directing or the acting. I don’t think a lot of people look at Taxi Driver and think, “Wow, the writing was awesome.”

Contrast that with another famous 70s film, Chinatown, where the writing is very much at the forefront of why people loved it. In these instances where you’re not sure if the writer deserves the recognition that’s given him a career, you look at their body of work. And Paul Schrader’s body of work seems to stir up more questions than answers. He wrote Raging Bull four years later in 1980. But, after that, he has a bunch of movies that fell short of expectation. The Last Temptation of Christ. The Mosquito Coast. Affliction. Even 1999’s Bringing Out the Dead, which got some buzz, ultimately fell short of the mark.

If there’s a lesson to be learned from Schrader’s career, it would be how important a great character is. He found that captivating haunted conflicted man in Travis Bickle and that carried the movie. Cause Taxi Driver is – I hate to say it – not a very well-plotted script. But we don’t care because we’re so interested in the character. And as we learned with White Lotus, a character can become the plot as long as their internal conflict is strong enough that the audience wants to stick around to see if he can resolve it.

While all of you are angrily constructing your “White Lotus isn’t in the same stratosphere as Taxi Driver” comments, I’m going to summarize The Card Counter’s plot. I’ll meet you on the other side…

42 year old William Tell is a card-counter who travels across the country using his special skill of counting blackjack cards to always beat the house. The trick to Tell’s longevity is that he bets small and wins small, trying to keep his winnings under a thousand dollars at every casino. That way, he won’t draw attention to himself.

That changes when a 40 year old woman named La Linda watches him clean up one night and asks him if he wants to be staked by an investor so he can win a lot more money. Tell says no thanks and, a few days later, visits a military-themed exhibition where a speaker recalls his experiences in Iraq.

A 20 year old kid named Cirk pops up and tells Tell he recognizes him. It’s at this point that we learn Tell’s history. He was once an interrogation officer at Abu Ghraib. Tell got screwed because he was caught in several of the infamous pictures that surfaced from the torture camp even though he did not, himself, participate. Cirk tells Tell that he wants to kill the real man responsible for the torture who never had to face any consequences.

The next day, even though Tell has no interest in helping Cirk harm this man, he invites him to come with him to gamble across the country. He also calls La Linda up and tells her he wants to get staked. He’s got a new plan. Make a ton of money really fast and then ditch gambling for good.

You may be thinking that Tell then goes off and plays a lot of blackjack, right? Because the script is called The Card Counter? Well you would be stupid then because, instead, Tell decides to play poker! Where is this script going? What’s going to happen next? I wish someone could tell me because I certainly don’t know.

When I started reading this script, my first thought was, “Whoa, this is really good.” When La Linda sits down with Tell and says, “I want to back you for a lot more money so we can both win a lot more money,” and Tell lays out why that’s a bad idea but decides to do it anyway? Everything looked great. I was all in for that movie.

And then the torture backstory started. At first I thought, “Okay, this is kind of interesting. It certainly makes Tell a more complex character.” But then the torture storyline kept getting bigger and bigger and bigger. Until the gambling plot was relegated to second fiddle.

Clearly, Schrader had two movie ideas and decided to combine them into one script. I see this happen every once in a while and it always feels like a good idea to the writer at the time. The idea is that you never would’ve written either script individually because you were afraid there wasn’t a big enough story. So combining the two scripts immediately feels like it solves the problem. But I’m telling you, two-idea scripts rarely work. There’s this constant cage match going on between the ideas as they fight for script superiority and the reader is never entirely sure what the script is about. So I highly advise against it.

It’s so sad when screenwriters make a bad choice in a good script. I know everybody here looks at screenwriting from the writer’s side. But to give you some perspective from the reader’s side, it’s so rare that you actually read something that pulls you in. However, even when this rare exciting feat happens, there’s always a voice in the back of our head saying, “Please don’t screw it up please don’t screw it up.” Because, unfortunately, that’s what usually happens. A bad choice is made and the whole script falls apart.

When the producer of The Shawshank Redemption, Niki Marvin, read the script for the first time, she had to put it down after the end of the second act because, in her words, it was so good that she couldn’t keep reading in case it fell apart. I didn’t understand that at the time but I understand it now.

Look, at least some of this could’ve been avoided by using a different title. “The Torturer” (or some other title about torture). Readers get the most pissed off when you pull a bait and switch on them. You’ve promised one movie, which the reader is excited about, but then give them something else. At least you guys now know what you’re in for so you won’t be as upset as I was about The Card Counter. But either way, I’m confused by the odd choice.

Even beyond that, the script had issues. It makes little sense why Tell invites Cirk to come with him other than Schrader was determined to add a “mentor-mentee” relationship to the story. You’ve established Tell as this loner who doesn’t get close to anyone. But now he’s inviting a 20 year old kid to spend the next few months with him? Even Schaeder seems to acknowledge the ridiculousness of the contrivance, having Tell utter this line via voice over a mere five minutes into their first leg of the trip: “Who is this insolent little prick? How did I ever end up here? I should just pull to the side of the road now, toss him on the ground, and stomp on his fucking head until it cracks wide open.”

To summarize, I don’t think The Card Counter ever figures out what it wants to be. It’s about a blackjack player… who plays poker. It’s about a loner… who invites someone on the road with him. It’s about gambling… except it’s about torture. It’s thematically all over the place and I’m guessing that the main reason it’s got good reviews is because Oscar Isaac gives a strong performance. No way it’s because of the writing.

I don’t recommend this one.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Be aware of how influential a title can be on the reader. It’s the first thing they see so it creates a strong expectation. If your script then deviates from that title, expect disappointment from the reader. This script should’ve been titled The Poker Player or The Torturer long before it was titled The Card Counter.

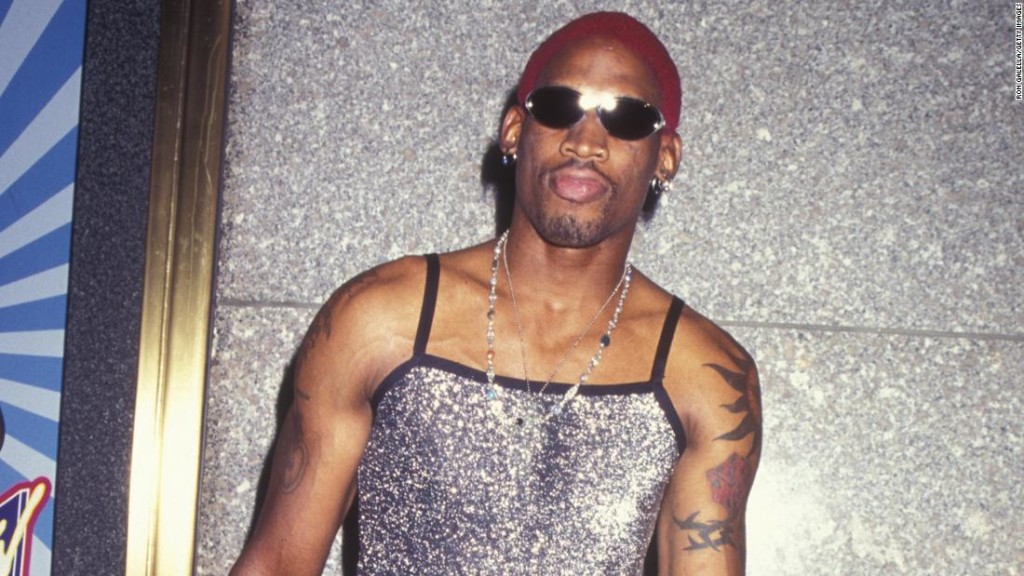

Genre: Comedy

Premise: Based on a true story, we follow Dennis Rodman in 1998 on a 48 hour Vegas bender with a young reluctant Chicago Bulls assistant GM right before Game 6 of the NBA Finals.

About: This script just sold the other week. It’s got an interesting backstory. There were actually two competing “48 Hours in Vegas” Rodman projects being circulated around town. The other one was about to sell to Netflix but stalled. This one then sold at the end of August. The other one is now trying to use the buzz from this sale to sell to a competing company. Lord and Miller are producing. I found this quote from Miller about the project and Rodman: “That is what made him a target and it’s also what made him a star. His weekend in Las Vegas is full of fun and high jinks but it is also full of important questions about the way public figures, and workers are treated, especially when their individuality is expressed so vividly.” There is absolutely ZERO of that quote reflected in the script. Any attempt to say there is deeper thought put into this script is an outright falsehood. The writer, Jordan VanDina, wrote a movie called The Binge which was a comedic take on The Purge. One day a year, all drugs are legal.

Writer: Jordan VanDina

Details: 98 pages

Readability: Mostly fast

A little background here.

I grew up in Chicago. When I was a kid, the Chicago Bulls were everything. That group of athletes and the party they brought wherever they went was, I’d imagine, the closest thing to the Beatles there was at that time. And when Dennis Rodman joined the team, it somehow went up a level. I still remember him announcing one day that he was going to get married, then a couple of days later showing up to a press event in a wedding dress and claiming he was going to marry himself. I had no idea what was going on with this insane man but I absolutely loved it.

So I sort of understand this sale. Rodman is such a character that it was probably inevitable that someone would look at him and say, “Why don’t we make a movie about this guy?” But from a studio perspective (Lionsgate purchased 48 Hours), the sale is odd. I can’t think of any script sale in history quite like it – a real life sports comedy based around such a goofy scenario. I guess this is the new era of movie deals. Streaming has thrown such a curveball into the process that we’re seeing things we’ve never seen before. I’m curious to find out if the script is actually good.

Our story starts in 1998. The Chicago Bulls basketball team has won five championships and is one game away from winning a sixth in Utah against the Jazz. But the Bulls’ top rebounder, outsized personality Dennis Rodman, in addition to having a bad Game 5, broke his penis by trying an acrobatic move in his most recent sexual encounter. Rodman tells coach Phil Jackson he’ll be in Utah for Game 6 in 48 hours. But first he has to clear his head… by going to Vegas!

Jackson, a bit of a weirdo himself, understands this request and grants it on one condition. He must take 27 year old Chuck Reynolds, a sheepish nervous uptight weakling of a man who happens to be dating Phil’s daughter. Rodman says if that’s the only way he can go, then that’s the only way he can go!

When Chuck goes to pick Dennis up, he finds that Rodman is dead. He then sees a video that Rodman left him explaining that the police are coming and Chuck will be arrested for his murder. But then – ZOINKS! – a live Rodman appears, says he was just joking, and brings Chuck to his limo. It is at this point that THE MOVIE SHIFTS INTO ANIMATION. Guess we’ve got another Space Jam on our hands!

It doesn’t take long for Chuck and Rodman to get stopped by the cops and end up in jail. After Rodman gets them out, they hop on a plane to Reno, where Rodman adds another notch onto his mile high club membership. Why Reno and not Vegas? Because Rodman really likes a steak restaurant there. Rodman does everything in his power to loosen Chuck up in Reno, even forcing him onto a mechanical bull. But Chuck can’t seem to shake his uptight approach to life. He pleads for Rodman to end the adventure and get ready for Game 6.

Yeah, like that’s going to happen. Rodman, who seems to have no understanding of money whatsoever, rents a Ferrari for them to drive up to Vegas in. Along the way, they crash the thing over a cliff. Eventually, Rodman starts to doubt if he’s providing anything of value to the Bulls and decides not to play in the final game. It will be up to Chuck to convince him that he’s essential and get Rodman to the game on time!

I would love to say that today’s writer finally broke the spell of bad Hollywood comedy scripts that have been coming through the system in the past seven years. Is this FINALLY the hilarious comedy script we’ve all been waiting for that blows the town away? Let me think of how to answer that question. Uh…

No.

Hollywood comedies have become too standardized over the last 7-10 years: Force two opposites together and throw them on an adventure. It’s not a bad formula by any means. If you get the right combination of characters with the right amount of chemistry who riff off each other in just the right way, you’ve got gold.

But whenever Hollywood only allows one formula in a genre, it’s inevitable that that formula will grow stale. Which is exactly what’s happened to the ‘mismatched duo’ genre. It’s officially stale. I didn’t love the Vacation Friends script, as you know, but at least they gave you a slightly different set up. Instead of two opposite people, you had two opposite married couples.

I mean look. All comedies come down to one thing – did they make you laugh? This script made me giggle twice. In 100 pages. Two giggles. I don’t even remember what I giggled about. In retrospect, I may have inadvertently tickled myself.

Here’s what I think the problem is. It’s a very nuanced discussion because the line between what 48 Hours in Vegas does and what it’s trying to do is very thin. The problem is that the writer is trying so so so so so so so so so hard to make Dennis Rodman funny. He wants you so badly to laugh at everything Rodman says or does. We feel that “try-hard” attempt at humor in every scene and it just cuts away at the humor.

The reason Alan in The Hangover works is because he’s not trying to make an audience laugh. That’s who he really is! That’s so important for comedy writers to understand so let me repeat it. A comedic character should never be trying to say something outrageously funny that would make an audience laugh. Why? Because THEY DON’T KNOW THERE IS AN AUDIENCE. They don’t know they’re in a movie. The only reality they know is the one in front of them. And so the only laughs that should come from them are when they’re trying to make someone else in the scene laugh or when they’re being themselves, and “themselves” just happen to be funny.

A movie character is not a standup comedian who purposely goes on stage to try to make people laugh. They’re just living their lives. So any humor should stem from them being themselves as they navigate through life.

Here are a few Dennis Rodman lines so you know what I’m talking about:

“Probably is the cousin of definitely and the great uncle of absolutely. I’m taking that as a yes.”

“Chuck, if all your friends jumped off a bridge into a fountain of fudge would you follow?”

“There is so much other stuff going in Vegas. I’m telling you, going 200 in a Ferrari doesn’t even crack the top 1,000 terrible things happening right now. One time I watched a baby sell weed to a bail bondsman.”

These are “please laugh” lines. There isn’t any authenticity to them. Which is the bigger problem I had with the script. It chooses the path of outrageous humor, and whenever you leave planet earth to do your comedy, there’s no baseline for why we should be laughing. It’s just who can say or do the most outrageous thing.

Take that Ferrari line above. A minute later, the two of them launch off of a cliff and go diving to a certain explosive death. But, what do you know, Rodman has a parachute with him – because of course he does – and grabs Chuck, leaps out, and parachutes to the ground.

Is that funny? Cause I would argue it’s too outrageous to be funny. In fact, I would say that this joke works a thousand times better in Space Jam because, at least, in that movie, you’ve established that a world where people fall off cliffs to their death is organic. Here isn’t just random and desperate.

Some would say that National Lampoon’s Vacation does not exist in any sort of reality. The family takes a Disney World guard at gunpoint and forces him to take them on all the rides. Would that ever happen? Not a chance. But National Lampoon’s Vacation is realistic ENOUGH that we buy into the world and laugh when the characters encounter these situations. 48 Hours in Vegas never even attempts to find reality.

And look, some of you are probably arguing that this is an animated comedy and therefore it shouldn’t be graded on whether it’s “realistic” enough. That’s a fair argument. But all I care about is funny. And the fact that this story doesn’t exist in any reality you or I know leaves all of the jokes feeling try-hard and, therefore, falling flat.

You’re probably asking the obvious question. So why did it sell? With comedies, it typically comes down to somebody wanting to make that kind of movie. They see the comedy in the concept, not the execution. Most executives at studios believe they can cast the funny into a script. That as long as the bones are there for lots of comedic scenarios, that once they get Melissa McCarthy and Kevin Hart in there, they’ll do the rest.

However, that does not mean you, the unknown screenwriter, shouldn’t execute the hell out of your premise. Focus first on coming up with a concept that multiple people who aren’t your mother think is funny. Or, at the very least, do what 48 Hours in Vegas does, which is to use a tried-and-true marketable comedy formula (mismatched buddies on an adventure). If you do that, you’re starting off with a major advantage. If you can then, also, execute a really funny story, you’ll be ahead of 99% of the writers out there.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Today’s sale would seem to signify that real life *comedic* stories in the sports world are now open to potential script sales. And since that’s a fairly untapped market, there are likely thousands of stories out there for the taking.

It’s the LAST DAY of White Lotus Is Amazing Week. I know that some of you are going to go in a deep depression after this. Just know that there are outlets where you have support. White Lotus Discussion reddit threads. Youtube interviews with the cast and crew. I’ll be publicly recreating scenes from the show at Griffith Park this weekend for anyone who wants to stop by. Don’t worry, the Steve Zahn opeing shot will be censored. That was one of the first things the Los Angeles Public Parks Department demanded when I applied for the permit. But sadly, starting Tuesday, we’re going back to a White Lotus Free Zone. Feel free to pay your respects in the comments section.

Our final topic of discussion is going to be the intersection between plot and character.

One of the common criticisms I’ve been hearing from the WLHA (White Lotus Haterz Association) is that there’s nooooooo plooooootttttttt. Nothing happens! It’s just a bunch of characters walking around a beach doing nothing. What gives? How could anybody find that interesting?

It’s a good question. I agree that White Lotus doesn’t have a ton of plot. But I still think it’s exceptional. Why is that? And how can one write a show or a movie that’s light on plot and still good? I’ll answer that in a second. But first, let’s talk about what plot is because it’s often misunderstood.

Google defines plot as “the main events of a movie devised and presented by the writer as an interrelated sequence.” I’ve heard numerous variations of this definition, probably the most common being, “A series of connected events that happen one after another.”

But I don’t think that captures the full breadth of plot. When you’re talking about plot, there’s a creative component to the variables in the story that needs to be included. When George Lucas comes up with this idea that the Death Star is on its way to destroy the Rebel Base, there’s a lot of creativity that goes into that choice. The idea of a moon-sized base that can blow planets up may be more imagination than plotting. But the base has such an outsized influence on the story, dictating so many plot-threads, that it’s essentially part of the plotting.

I guess what I’m saying is, plot isn’t just the conveyor belt that moves the story along. It’s all the creative elements within the story that affect what’s happening.

I bring this up because, typically, if you’re writing something that’s character-based, it’s a good idea to throw in some creative plot elements to spike the story. Get Out is a good example. It’s a character piece but a lot of crazy things happen during the plot to spike it. Meanwhile, White Lotus doesn’t have many creative plot elements at all, which, I’m guessing, is why the WLHA are so underwhelmed.

They’re probably wondering why I like a show such as White Lotus when I’ve dinged so many screenplays before this for having little to no plot. A recent example is Dust, the script I reviewed last week about a woman stuck in her house during an extended dust storm. I hated that script mainly because NOTHING HAPPENED. So why does White Lotus get a pass and Dust doesn’t? Well, let’s find out.

When you write a character piece, you’re essentially wiping out the “EXTERNAL CONFLICT” portion of the plot (which I talked about yesterday). You’re taking out the killer tsunami. You’re eliminating the bank heist. Nobody’s asking you to jump into multi-verses to capture other versions of yourself. The big external conflict factor is eliminated in favor of internal and interpersonal conflict.

Our plot, then, is the unresolved conflicts *within* the characters as well as *between* the characters. Here’s how the formula works. The writer comes up with a group of characters. For each character, they make them either likable, sympathetic, or interesting. This is what “hooks” the reader. They either like, sympathize, or are intrigued by a character. They’re now invested in that character’s actions and want to see what happens to them.

From there, you figure out the internal conflict. Remember, the internal conflict in a character piece is going to become a plot thread. We don’t have Thanos threatening to kill anyone so the plot needs to come from the character. Mark (the father) learns from his uncle that *his* father, who died a long time ago, didn’t die from cancer like he was originally told, but rather from AIDS. Mark learns that his father was gay and used to sleep with men outside the marriage.

This becomes Mark’s internal struggle. Nothing about his childhood is real anymore. It’s all a lie. Which means Mark’s out of balance. He doesn’t know how to reconcile this new information. So this vacation is him trying to come to terms with this new information and figure out what it means for him as a father and as a husband.

Mark’s journey to find balance within himself is the PLOT of a character piece. As is Rachel’s (the young beautiful wife) journey to figure out if she wants to be a trophy wife for the rest of her life. As is Tanya’s (the older socialite) journey to move on from her mother’s death. As is Quinn’s (the 15 year old social anxiety-ridden son) journey to connect with the world for the first time, which is resolved when he joins the local rowing team.

Now, if you don’t like these characters, you’re not going to care whether they resolve these issues or not. You don’t have the flashy entertainment factor of a James Bond plot to fall back on. It’s just a bunch of unlikable people to you. That’s why you’re bored. But to those of us who like the characters, their journeys to either resolve or fail to resolve these issues is why we watch. We’re fascinated by these people so of course we want to know if they figure themselves out.

The second area where you create plot in a character piece is through unresolved relationships, which we talked about yesterday (interpersonal conflict). If you attempt to plot your movie solely through internal struggle, it’s not going to be enough. Even the most ardent cinephiles need something going on *outside* of the character to be interested. Which is why interpersonal conflicts become so important in a character piece. They’re your main plot engine.

Mike White knew this which is why he spent so much time on the relationships. Will Shane get the Pineapple Suite from Armond? Will Olivia and Paula get their drugs back from Armond? Will Rachel leave Shane? Will Mark and his son connect? Will Mark and Nicole fix their marriage? Will Belinda get the investment to start a new business from Tanya? What will Olivia do about Paula sneaking around behind her back?

To those of us who like these characters, we can’t wait to see how their conflicts are resolved. That’s what’s confusing to those who dislike the show. To them, they’re wondering, “Why do people like this? Nothing’s happening. There’s no plot.” Well, once we became hooked on these characters, their unresolved conflicts were enough of a plot for us. And that’s true for any story, which is why characters are so important. If you can create captivating characters, readers will follow them through weak plots, messy plots, plot-hole filled plots. Which is why I say characters are the most important element of any screenplay.

To summarize, if you create a character we’re interested in, give that character an internal unresolved struggle, then give them between 1-3 interpersonal unresolved conflicts with other characters, that can be enough to plot a story. You’re still on the hook to come up with twists and turns and interesting developments within the story – such as Shane’s mother showing up on the honeymoon – but if you get those three things right (character we like, compelling internal struggle, compelling interpersonal conflicts), you too can write a show as awesome as White Lotus.

And that concludes White Lotus Week. I hope you enjoyed it as much as I did. Monday is Labor Day so I’ll catch you back here on Tuesday!