Search Results for: girl on the train

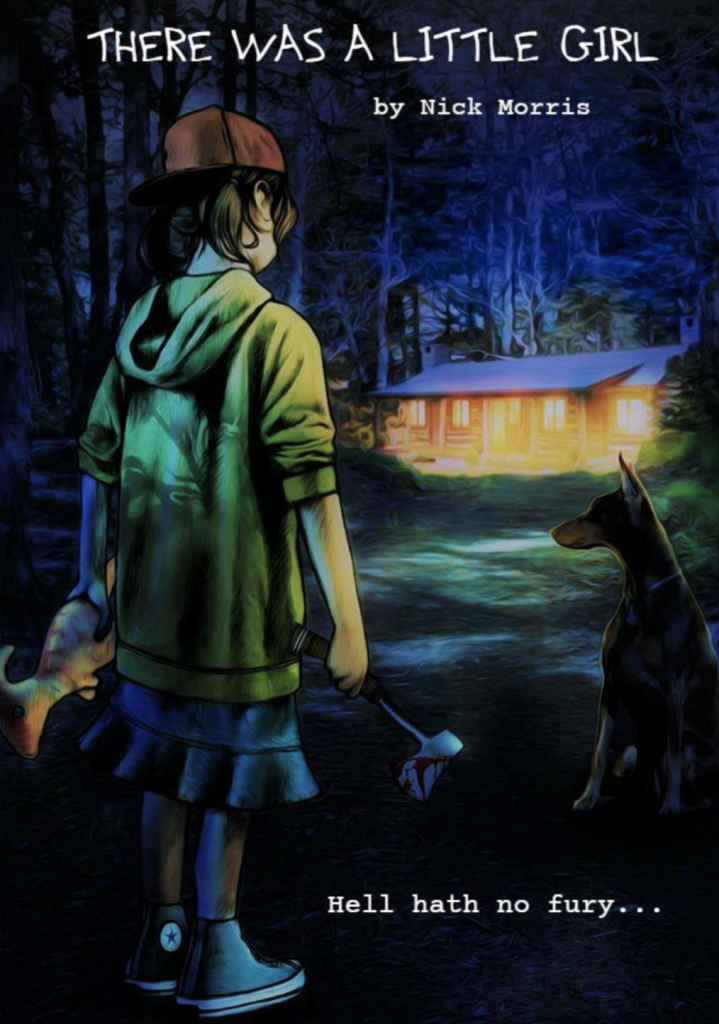

Are you ready… for Die Hard with a 9 year old girl?

Genre: Horror/Thriller

Premise: After witnessing the murder of her daddy, nine-year-old Becky and her dog set out to teach the scumbags responsible that Hell hath no fury like a pissed-off little girl with nothing to lose.

Why You Should Read: It’s my belief that somewhere deep within the human psyche there exists a zone of intense fury that, thankfully for most of us, will never manifest itself. A level of rage that can only be triggered by a morally reprehensible and personal transgression – like the murder of a loved one. That’s the core idea that kept insisting I write this script. And the most compelling perspective I could think of to explore that idea from was that of a young kid. So I knew going in that it could be polarizing and striking the right tone would be tricky. But I’m very pleased with how it’s come together and would really love to hear the thoughts of the ScriptShadow community. Thanks for looking!

Writer: Nick Morris

Details: 93 pages

A long long time ago I remember seeing a trailer for a movie called “Blue Streak.” It starred the great one himself, “Big Momma’s House” actor Martin Lawrence. The setup for the movie was: Martin Lawrence’s criminal protagonist knows the police are about to catch him for stealing a diamond, so he hides the diamond in the ceiling of a building under construction. He’s later caught and sent to prison. Two years later he gets out and comes back to retrieve the diamond. Only now the building is… a police precinct. So Martin Lawrence must pose as a cop to retrieve the diamond.

When I saw that trailer, I thought to myself, “That has to be the greatest setup for a movie ever!” I mean, what a clever concept. Now since then, I no longer believe it’s the best idea ever. But it’s still a damn crafty idea. As a plot device, it’s as clean a setup as you’re going to get. Someone has to ditch something illegal then come back to get it later, except now the conditions aren’t ideal for retrieval.

That’s the setup for today’s script. But the question we’re all wondering is, can it survive without a role for Martin Lawrence?

Jeff is driving his 9 year-old daughter, Becky, up to their cottage with their two dobermans, Diego and Dora. Becky’s still reeling after the death of her mother and is furious that Jeff is bringing up a new woman for Becky to meet, Kelly. Jeff assures Becky that no one can ever replace mom, but to please give Kelly and her 5 year-old son, Ty, a chance.

Becky’s not having it, storming off to her tree-house after Kelly and Ty arrive. Little does Becky know, her tantrum may have saved her life. Four escaped convicts, leader Dominick, muscle Apex, pervert Cole, and pedophile Hammond, descend upon the house looking for a key Dominick hid there ten years ago.

The four rough up Jeff, Kelly, and the kid, asking for the key, before Dominick realizes a young girl is out there, and she may hold the literal key he’s been looking for. So Dominick sends his boys out to go look for her, but Becky quickly outsmarts them. And when she gets Cole in a compromising position, she slams a broken wine-glass handle through his eye, killing him. It’s on!

(spoiler) Unfortunately for Becky, Dominick blows Jeff’s head off, which technically makes Becky an orphan. It also makes her pissed. So while Dominick’s men run around the property in search of that key, Becky runs around in search of revenge. And she’ll use any graphically violent means possible to get it!

One of the things we talk about here is irony. A big tough muscular guy working as a bouncer is expected. A small weasly geek with glasses working as a bouncer, and being good at it, is ironic. You’re looking to add irony wherever possible in a screenplay because it’s one of those things that, when done well, works like a charm.

Nick took that route here. Instead of a tough-as-nails New York Cop running around a property killing bad guys, Nick inserts a clever 9 year-old girl. It’s ironic, so it’s good, right?

Well, the thing with screenwriting is that sometimes rules collide. Something you’re told you should do overlaps with something you’re told you should never do, and a judgement call needs to be made. You can make the argument that There Was A Little Girl violates one of the most important rules in screenwriting: suspension of disbelief.

Is it believable that a 9 year-old girl could take down a group of big burly criminals in a non-comedic setting? I’d have a tough time believing that 9 year-old girl would have the strength to even stab someone with a wine glass handle.

However, there may be a solution to this. One thing I could buy into was a 9 year old girl with two full-grown trained Dobermans killing a group of men. If you kept both dogs alive and she used them for the bulk of her attacks, I might be able to buy into that. Maybe they were even fight dogs that Jeff rescued. So they have killing in their DNA.

The thing I’m more concerned with in There Was A Little Girl, though, is the dialogue. It lacks color. Throughout the first half the script, almost every line of dialogue is very basic, one or two lines. There’s zero spice. Here’s an example. Jeff greets Kelly when she arrives…

“Man, I have been waiting for this.” “Me too (looks around) Wow, you weren’t lying. This is beautiful!” “Thanks. You found it no problem?” “Yeah, well, I found it. Your sketchy-ass directions were no help. Thank God for GPS.”

‘Sketchy-ass directions’ is as colorful as the phrasing gets in this script. And it’s rare.

Look, dialogue has always been a weakness of mine. I’m aware of how difficult it is to write. But you at least have to try. Add some color SOMEWHERE. Here’s Dominick’s longest chunk of dialogue in the script: “Christ. I do not need this shit right now, Apex. Okay? There’s no time. There’s just no fucking time. I’ve been here too long already. They’ll be out searching by now. Door to door. Even if they don’t remember this place, they’re still gonna eventually show up here. Right?!”

The sentences are all very short, very to-the-point. There’s zero color. Check out Tommy Lee Jones’s famous line in The Fugitive: “Alright, listen up, ladies and gentlemen, our fugitive has been on the run for ninety minutes. Average foot speed over uneven ground barring injuries is 4 miles-per-hour. That gives us a radius of six miles. What I want from each and every one of you is a hard-target search of every gas station, residence, warehouse, farmhouse, henhouse, outhouse and doghouse in that area. Checkpoints go up at fifteen miles. Your fugitive’s name is Dr. Richard Kimble. Go get him.”

Is it fair to compare Dominick’s line to one of the most popular movie lines in history? No. But I’m trying to make a point. You need to do more with dialogue than just keep the plot moving. Especially in a script like this where you have criminals. Criminals are ideal vessels for spouting colorful dialogue. That’s the first thing I’d tell Nick to do here – do a dialogue pass and FIND THESE CHARACTERS’ VOICES!

Lastly, the plot is too predictable. I was way ahead of the script, often waiting for the writer to catch up to me. (spoiler) Jeff’s death might have been a surprise had I not read the logline. But that was it.

I’ve found that you can sometimes get away with a predictable plot. But only when the character development is strong. In other words, you’ve got to give us one of the other. You can’t give us neither. And There Was a Little Girl had neither. Apex’s conscience was the closest thing we got to a character arc. We needed more.

This is the second amateur script I’ve read in a row (not last Friday’s script, but a consultation) where the writer could’ve benefited from more time with the characters before the inciting incident. That would’ve allowed us to give the characters clearer flaws so we knew what they needed to work on. I know everyone’s afraid that if they start the script too slow that the reader will get bored. But if you give us a teaser that rocks our world (and There Was a Little Girl had a pretty good teaser), you can take your time setting up the characters before the inciting incident occurs. I barely knew Kelly before Dominick showed up. And since she’s the one who survives between her and Jeff, that was a problem, since I could care less about a woman I barely knew.

I like the marketing image of a girl (who will need to be older) with two vicious dobermans staring into a house at night. But this is a tricky one. Will people buy tickets to a movie with this young of a lead that’s this violent?

Script link: There Was A Little Girl

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: How do you add color to dialogue? Here’s a trick. Think of all the people in your life, past and present, who have weird/unique/fun/interesting ideas/thoughts/speech-patterns/obsessions. Find one that’s similar to your character and write the character the way that person speaks. I was briefly friends with a guy who’d spent a year in China. All he could talk about when you brought up anything was how differently they “did it in China.” It became so annoying that I Peking ducked out of that friendship. However, those are the types of people you’re looking to for inspiration if you want to add color to dialogue.

You’re allowed to play around here on Amateur Offerings for a teensy bit, but you should really be working on your outlines and character bios, especially if the weekend is one of the only times you get to write. With that said, here are this week’s entries. Read and vote on your favorite (just add a comment with your vote). Whoever gets the most votes gets a review on the site next Friday! May the best script win…

Title: Onion

Genre: Psychological Thriller

Logline: In order to fend off a home invasion, a troubled man descends into a fierce, animal-like state – from which he seems unable to emerge – and goes on the run in an increasingly violent, single-minded quest to return to his childhood home.

Why you should read:

– Received both a 5 and a 9 on the Blacklist website. What’s with that – or more importantly, which one is it really closest to?

– Vicarious wish fulfilment for anyone who’s been bullied;

– Some jaw-dropping ‘can’t believe that just happened’ moments;

– An amazing third act TWIST – which I bet you won’t see coming.

Title: Pandora’s Box (this week it works!)

Genre: Supernatural horror

Logline: After the tragic death of their five year old son Ryan, the Taylor family begin to experience

paranormal phenomena. In a desperate attempt to contact their son, the family turn to a Voodoo

witch, who is cursed with the gift, to see the dead.

Why you should read: Do you love rainbows? Cute and cuddly care bears? Unicorns? Rose smelling farts? If so, this is NOT a script for you. I repeat, this is NOT a script for you. I eat cute and cuddly bears and shit out unicorns for breakfast. This is a script that will make your legs quiver (like a dog taking a shit), this is a script that will make The Sixth Sense look like a romance movie (That’s just trash talk, The Sixth Sense is one of my all time favorite movies). If, like me, you love suspenseful horror, and you love to shit your pants (like a crying baby) then maybe… Just maybe, this is a script for you. A low budget horror, in the genre of The haunting (1991), Insidious, The Conjuring, and The Shining, “designed to jack you up”.

I hope you enjoy guys, and thank you for taking the time to read Pandora’s Box, co-written with my sister, (yes, we need MORE female writers)!

Title: The Other Princess

Genre: Comedy, Romance (live action)

Logline: When a broke kingdom gets a second chance with a sponsored contest to find the “next Cinderella,” a common girl who competes to help her family must decide if all the drama and a charmless prince are really worth it.

Why you should read: A while ago I was watching Shrek with my toddler niece, and thinking “I would’ve loved a whole movie on the funny fairy tale kingdom stuff.” That thought led to: “imagine if after the Cinderella story, Fairy Godmother became a washed up drunk”…and “imagine if another kingdom tried to find the next Cinderella through a “Bachelor” like competition”…those were just a couple of the “imagines” that resulted in this script, and if it’s something that might appeal to you, I hope you enjoy whatever you have time to read! (as for me: my background began in narrative fiction, and after publishing 3 novels, I started learning all I could about screenplays, as it seemed natural given my love of writing dialogue. A previous script was a top 20 finalist with Script Pipeline in 2014, and with this new one I’m just trying to see if readers find it interesting and fun!)

Title: Game. Set. Match.

Genre: Sports/Drama

Logline: On the day of the U.S. Open Championship, a washed up tennis-star, facing his last chance at winning a Major, is presented with a tempting offer to throw the match to his opponent: his younger brother.

Why you should read: I’ve been writing screenplays for about 5 years now, but in the last year I’ve gotten very serious about it and am moving out to LA next month. Over the past year, I’ve really pushed myself to write as many scripts as possible, and I think that Game Set Match might have some potential. I know that sports dramas aren’t exactly the sexiest drama and neither is tennis (despite Maria Sharapova’s efforts), but I think this story is told in an interesting way and will pull people in. Other than that, there’s some racket smashing and John McEnroe… what more could you ask for?

Title: Fiesta (The Sun Also Rises)

Genre: Drama/Adaptation

Logline: A eunuch suffering from PTSD makes a trip to Spain with the woman he loves, succumbing to the hedonism and despair consuming post-war America in the 1920s. Don’t worry. There’s also bull-fighting.

Why you should read: I can’t remember Script Shadow ever reviewing an amateur script that’s ALSO an adaptation. I understand there are a bunch of reasons for this

1. An unproven writer should not be adapting major material he doesn’t own the rights to.

2. See above dummy.

But…

1. I really wanted to see this wonderfully poignant and romantic story as a movie. There is a version (50s), but it kind of blows. So I wrote it. Out of love, passion and with absolutely no notion it could ever be made. I’m very proud of it, and just wanted to have an advanced reader let me know what they think. After all, getting screenplays read is hard, but getting screenplays read that require literary rights is impossible.

2. Wouldn’t it be cool to examine an amateur adaptation? It’s certainly something that’ll probably prove unique from other reviews. I can definitely take the licks that might arise from such a scenario.

I’m probably really dumb. But I wanted to see this thing as a movie. This was the way to do it. It would be amazing to hear what you think.

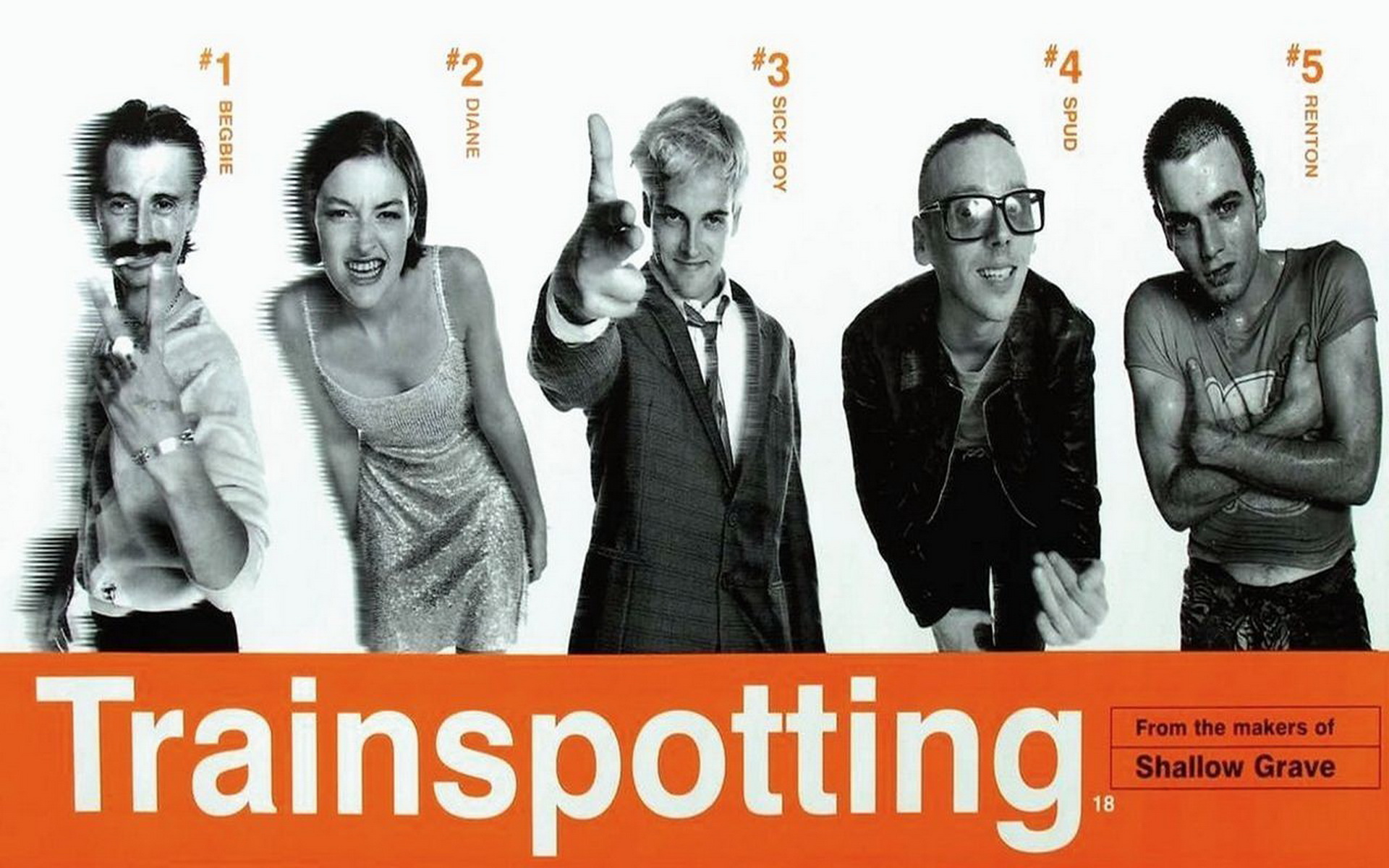

You may remember Trainspotting as one of those 90s movies that was changing the guard in Hollywood. Writer-directors Tarantino and Rodriquez were rewriting the rules on how stories should be told. Screenwriters like Shane Black were changing the way screenplays were written. And then this British heroin-addict flick came along and landed perfectly within that counter-Hollywood culture that many assumed would change the way films were made forever. Well, that change both happened and didn’t happen. There’s definitely more of a “do-it-yourself” attitude in today’s filmmaking community. But that brash no-holds-barred way of writing and shooting died off with the folding of most of the indie companies. It just wasn’t as easy to find money outside of the studio system anymore. So everyone started playing it safe again, and we really haven’t had a Pulp Fiction or Trainspotting for a long time. Frowney face. Based on the novel by Irving Welsh, adapted for the screen by John Hodge, and directed by Danny Boyle (Slumdog Millionaire, 28 Days Later), Trainspotting was nominated for a screenwriting Academy Award in 1996. It’s also ranked 10th by the British Film Institute in its list of the top 100 British films of all time. It just so happens that Hodge and Boyle have reteamed for the new James Mcavoy flick, Trance, which comes out soon. There have been persistent rumors that a sequel to Trainspotting will be made, with Boyle leading the charge, but Ewan McGregor has stated he wants to protect his character, and therefore doesn’t want to make an inferior second film.

1) When you have a lot of characters to set up, create a situation/scene that allows you to show us their differences – Here we have Sick Boy, Begbie, Spud, Tommy and Renton. Instead of giving them each their own individual scenes to set them up, which would’ve taken forever, Hodge throws them all into a soccer (football) game. We see Sick Boy commit a sneaky foul and deny it. Begbie commits an obvious foul and makes no effort to deny it. Spud, the goalie, lets the ball go between his legs. Tommy kicks the ball as hard as he can. This game allows each of the characters an individual action that tells us exactly what kind of character they are.

2) Voice over tends to work better when the pace is fast – When the story’s slow, it draws attention to the voice over, which in turn sounds preachy, as if it’s trying to carry a boring story. Trainspotting has one of the best voice overs in history (“Choose life. Choose a job. Choose a career. Choose a family. Choose a fucking big television. Choose washing machines, cars, compact disc players, and electrical tin openers.”). And a big reason it works is because the story’s moving fast (we open on our characters running from the cops). It’s not that you can’t use voice over with slow material. It just seems to fit better when the pace is quick.

3) Write a story that’s opposite in pace and tone from the subject matter – One of the cool things about Trainspotting is that it’s about one of the most depressing subject matters out there – heroin addiction – and yet the story is fast and fun a lot of the time. This contrast in expected pace and actual pace gives the story an unpredictable exciting feel. I mean imagine if Trainspotting would’ve been slow-paced and focused on all the depressing moments related to heroin addiction. It probably would’ve sucked, right?

4) CONFLICT ALERT – Remember, movies do not work without conflict. You need to mine it wherever you can. Conflict between characters is a given, but not always a necessity IF you have a strong inner conflict with one of your main characters. Here, it’s addiction. That’s what Renton (Ewan McGregor) is fighting. That’s his battle throughout the movie. Without it, this movie doesn’t work.

5) Once again, use voice over to help a story in need – We saw this with Fight Club, but here it’s even more evident. The more you shun structure, the more you need voice over. The opening of this movie is guys trying to steal items to sell so they can buy dope. Then a sequence where they come off heroin. Then they try to get a job. Then they’re all hanging out, going to bars. Then they’re back on dope. 30 pages in and no story (no goal) has emerged. But it all flows pretty seamlessly because Renton’s voice over is guiding us along. Use voice-over to patch up a patchy story.

6) Talky friend movies need a theme or a unifying element – In these types of movies that don’t have much of a plot and are basically a bunch of friends hanging out, you need a unifying element – something the story can keep coming back to. Failure to do so leaves you with a bunch of friends talking, and those scripts are both boring and concept-less. The way to make these movies work is to add that BIG unifying element. Fight Club had fighting. Trainspotting has heroin (or addiction). It turns a situation that really isn’t about anything and makes it about something.

7) Give your characters personalities – I think one of the problems with writers is they’re so focused on creating character backstory, character flaws, and character relationships, that they forget to give their characters an actual personality. You technically have an “interesting” character, and yet the reader thinks all your characters are boring. So after you’ve added those elements, simply ask yourself if your character has a personality. Are they someone who people would find interesting in real life? Take Sick Boy, for example. He can’t stop talking about those damn Bond films. His obsession with them is a dominant personality trait that helps define him. A personality is what ensures your characters will be memorable.

8) In non-traditional storylines (stories without goals), try to give your characters problems – While your story won’t have the same drive as a goal-fueled story, a strong character problem will ensure that the reader will want to keep reading. Take Renton, for example. He has sex with a girl and it turns out she’s 14. She then threatens to tell the police if he doesn’t continue seeing her. The less structured your storylines are, the more in need they are of problems for your characters.

9) If you’re going to do dream sequences, make sure they’re motivated – There’s nothing more amateur than a trippy dream sequence slapped into a script. They’re often weird, random and pointless. One way to write a dream sequence that actually works is to make sure it’s motivated. That way, it’s no longer pointless. A great example of this is towards the middle of Trainspotting when Renton is coming down off his addiction. He’s locked in his childhood bedroom and has an intense dream that includes babies on the ceiling and his doctor as a cheesy game show host. The dream sequence works because it’s motivated. The character would obviously have these delusions when coming down off his addiction.

10) For better dialogue, look for a playful alternative to a predictable conversation – After a court appearance where he agrees to rehabilitation, Renton heads to his dealer’s apartment. Now this conversation could’ve gone like this: “Give me the hit of all hits.” “That’s going to cost you.” “I don’t care. I need it.” Borrrr-ing. Instead, we get this, RENTON: What’s on the menu this evening?” SWANNEY (DEALER): “Your favourite dish.” “Excellent.” “Your usual table, sir?” “Why, thank you.” “And would sir care to settle his bill in advance?” “Stick it on my tab.” “Regret to inform, sir, that your credit limit was reached and breached a long time ago.” “In that case –“ He produces twenty pounds. “Oh, hard currency, why, sir, that’ll do nicely.” Renton prepares. SWANNEY: “Would sir care for a starter? Some garlic bread perhaps?” “No, thank you. I’ll proceed directly to the intravenous injection of hard drugs, please.” Way more fun of a scene, right?

Genre: Action Comedy

Logline (4th place): When a meek and universally abused copy editor is mistaken for the professional killer she accidentally bumped off, she decides to take on this violent new identity until the killer turns out to be not so dead, and very pissed off.

About: Welcome to the first annual “First Ten Pages Week.” What I did was have readers send in loglines then vote on their favorites. The top five loglines, then, would get their first 10 pages read. With any of this week’s reviews, if the comments are positive enough, I’ll review them in full on an Amateur Friday.

Writer: Emily Blake (check out Emily’s Blog – Bamboo Killers)

When this logline first came in, I admit I didn’t think much of it. I mean it was good enough to make the Top 50, but I wasn’t sure it would fare well against everyone else. Then it started getting all these votes and I was like, “Hmmm…Let me take a look at this again.” When I read it a second time, I realized it had more potential than I originally thought. In fact, it had the best title and logline *combination* of the five entries. What I mean by that is, of all the combos, I got the best sense of what the movie was by looking at the title and the logline together. And I can’t tell you how huge that is. When you’re on the outside of those pearly studio gates, your logline and title are the only two things advertising your script. So if you can come up with a combination that sells your story clearly, you’re in really good shape. For contrast purposes, compare this to Stationary, where we got a sense of the movie but didn’t get the full picture.

The first 10 pages of Nice Girls Don’t Kill start with southern Belle assassination queen Lana walking into a library and killing a librarian who owes her boss money. Cut to Mary Beth, who is the polar opposite of Lana. We observe her backing down from a confrontation with her defense class teacher, backing down from a trainer who bullies his way onto her treadmill, and backing down from an obese woman who cuts in front of her in line. Mary Beth is a girl who seriously needs to step up her game, but from what we’ve seen, it doesn’t look like that’s going to happen.

The pages…

First of all, we have a solid opening scene. Some nice atmosphere is created with an empty library at closing time, thunder cackling through the windows. A seemingly innocent girl taps on the door, asks to come in, and then assassinates the librarian. We have some nice dialogue in the scene: “Listen, honey. I’m a nice girl. I don’t do that whole bamboo under the fingernail shit, but if you paw at me again I will shoot off your shriveled old Willy, put a knife in your gut and leave you to bleed to death. Are we clear?” The only thing I didn’t dig was Lana singing “Cherry Pie” to her ringtone as she cleaned up her kill. It just felt a little forced. But overall, I was into it.

However once we cut to Mary Beth, Emily starts working a little too hard to convey her heroine’s fatal flaw. Conveying a protagonist’s fatal flaw is an art. You want to make it clear. But you don’t want to whack us too hard with it or it feels forced. In this case, we see Mary Beth kicking ass when she’s banging on the punching bag, but then unable to hit her instructor when he (she?) tells her to. The instructor goes apeshit on her for her weakness and even calls Mary Beth a giant pussy.

We follow this with Mary Beth on the treadmill staring at a slutty client flirting with a trainer. The duo then comes over and boots her off, and she meekly retreats to the locker room without saying a word. We then get a scene in the locker room where Mary Beth observes some badass woman taking charge. If only she could be that tough… We then follow THIS with a scene in the bus line where someone cuts in front of Mary Beth and she doesn’t say anything. And then, in addition to all of this, Mary Beth keeps spotting numerous advertisements for an energy drink called…yes…“Potential.”

I think it’s safe to say that Emily drove the character flaw nail into the 2×4, then kept slamming it until she split the board in half. Selling a character flaw is good. But at some point, you gotta let the customer experience the product for themselves.

Afterwards, Mary Beth walks up the stairs to her apartment, and there her landlord is, asking for rent. I have no problem with this scene. It raises the stakes and forces your character to act. But you have to realize, I’ve read maybe 800 scripts (no exaggeration) where a landlord wants rent from the protagonist. All I ask is for from the writer is to show this moment in a unique way. Simply having the landlord yell, “You’re late with rent,” is boring and predictable. You’re a writer. This is what you do. You come up with unique ways to spin familiar situations. Maybe Mary Beth comes home and finds her refrigerator gone. In its place is a note. “You steal from me? I steal from you. Pay your rent!” Maybe this is even a common practice. There are notes all over the apartment from things that have been stolen by the landlord. That may be a dumb idea. I don’t care. It’s better than the tried-and-true landlord (who, although not in Emily’s script, is almost always Eastern European) standing at the doorway and demanding rent when our hero comes home from a long day.

Nice Girls, all in all, was probably the toughest of the five entries to judge. There’s nothing really wrong here. I mean, yeah, there’s the fatal flaw repetition I mentioned above. But that’s an easy fix. Just cut a couple of those scenes and we’re fine. But there’s nothing I got too excited about either. Nice Girls falls into that dreaded category of “Good but not great.” Or, as the Hollywood types like to say it: “Liked it didn’t love it.”

So then how do we bring this up to a “love it?” Well, I’m going to offer the same advice I offer everyone. Professional readers spend *all day* reading scripts with the same scenes and the same plot points and the same characters and the same devices used to make us like or hate those characters. It’s all so familiar. So what gets us on the edge of our seat? When writers TRY HARDER. When they don’t go with the obvious choice. The “rent is due” scene is the perfect example. You need to TRY HARDER and give us something slightly different from what we’ve seen before. And you need to do that FOR EVERYTHING. If you even have an inkling that you’ve seen the scene you’re writing before? Try to come up with SOME SPIN, some FRESH POINT OF VIEW, that makes it read differently. Nice Girls Don’t Kill is too familiar in its current incarnation. And I think that if Emily were pushed more – had a development person on her ass – that she wouldn’t be taking these safe routes. She’d be pushing herself and coming up with better, more original, material. Since not a lot of us have a development person calling us on our bullshit, we have to depend on our inner development person. In other words, you have to call your own bullshit.

Would I keep reading?: Maybe. Truthfully, this is one of those scripts where I’d probably say, “I’ll give this until the end of the first act to pick up.”

Link: Nice Girls Don’t Kill (First Ten)

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Beware of “Pause scenes.” – “Pause scenes” are any scene where you pause your story to put something in that doesn’t push the story forward. The treadmill scene is a classic “pause scene.” There is no story information in this scene whatsoever. The only point of the scene is to tell us something about our character. And in this case, it’s to tell us something about our character that we already know, since we just saw Mary Beth back down from her instructor a scene ago. I’d argue that the changing room scene and the bus scene are also pause scenes. So how would you unpause the treadmill scene? Well, maybe Mary Beth’s best friend is on the treadmill next to her and they’re setting up later story points (“You’re coming out tonight to meet Bob. You know that right?” “You mean Ear-hair guy?” “He is a nice man with an ear-hair issue okay. And he’s a book nerd. Like you. You’re not getting any younger you know.” “Fine.”) Now you have STORY INFORMATION conveyed in the scene so the scene itself is actually necessary. If all you’re doing with a scene is telling us about your character, you’re writing a pause scene.

This is a book review. Not a script review. For those who know nothing about this book, I recommend you read it before reading any review. There are lots of surprises in the story, some of which I’ll be spoiling here. You’ve been warned.

Genre: Mystery/Crime

Premise: A disgraced journalist is hired by the head of an eccentric family to solve the murder of a girl 40 years ago.

About: The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo is the best-selling Swedish novel by Stieg Larsson and the first in a series of three books that have come to be known as the “Millennium Trilogy.” The books are so popular that Larsson became the second best-selling author in the world in 2008, behind Afghan-American author Khaled Hosseini. By March 2010 his Millennium trilogy had sold 27 million copies in more than 40 countries. Sadly, Larsson never enjoyed this success. He wrote the three books for his own pleasure every day after work and they were only published after his death from a massive heart attack at age 50. Larsson left about three quarters of a fourth novel on a notebook computer; synopses or manuscripts of the fifth and sixth in the series, which was intended to contain an eventual total of ten books. Recently, David Fincher signed on to direct the film, and is currently in the middle of a months-long search for the actress who will play the famed tattooed lead.

Writer: Stieg Larsson

First off, no, I don’t have this script. So I’m ordering radio silence on requests.

If you’re like me, whenever something big comes along that people say you “have to see” or “have to read,” you immediately go into Resistance Mode. A roll of the eyes. A tightening of the jaw. ‘Don’t tell me what I *have* to see. I’ll see what *I* want to see dammit!” And then you go on an illogical months-long strike of the movie/show/book for no other reason than to prove (to no one – cause no one’s paying attention) that you are not influenced by the fleeting tastes of pop culture. Okay, well, maybe that’s just me. Either way, I didn’t think I’d ever see the inside cover of the surely overrated Girl With the Dragon Tattoo. But then vacation came along.

And as you know when you’re on vacation, you have to “do things” that are “different,” in order to justify travelling hundreds of miles away somewhere. And since I never have the time to read books anymore and nobody would stop talking about this damn tattooed girl, I realized that Mr. Larsson and I were going to have to make up. It was time to stop avoiding each other. It was time for me to read The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo.

Tattoo follows two main characters, the unshakeable journalist Mikael Blomkvist and the anti-social genius Lisbeth Salander. When we meet the bright but sad-eyed Blomkvist, he’s been convicted of slandering the snake-like businessman Hans-Erik Wennerstrom in his self-published magazine, Millennium. This has put both his business and his name in serious jeopardy, and Blomkvist, who was quite a popular figure in Sweden, has been relegated to a petty criminal by the press. Things aren’t looking good for him.

But they’re certainly better than the life of 20-something Lisbeth Salander. An orphan for most of her childhood, Lisbeth’s been bounced around from family to family, guardian to guardian, most of whom were men who physically and sexually abused her. Even now, she must report to a guardian, a man who has control over her financial assets. Asking for money always requires a sexual favor in return. Lisbeth is just a tortured individual, a dog who’s been kicked every day of her life. She doesn’t trust a soul, especially men. The only happiness she finds is in her job. Lisbeth is a crack-researcher working for private eye companies to dig up dirt on people, usually large corporate types. It’s a job she enjoys because most of the people she gets dirt on are men. It’s a small way to return the favor and speed up the karmic train.

One day Blomkvist is visited by a mysterious man who informs him that retired entrepreneur Henrick Vanger, of the famous but dying Vanger Corporation, wants to offer him a job. Blomkvist travels to the isolated and spooky island of Hedeby to meet with the reclusive Henrick, who, after a considerable amount of backstory, asks Blomkvist if he would like to write a book about the Vanger family. Henrick won’t be above ground for much longer, and he thinks it would be important to chronicle the intricate cracks and corners of his large and complicated family history.

Henrick informs him that this is only the first half of the job. 40 years ago Henrick’s 16 year old niece, Harriet Vanger, disappeared here on the island. The circumstances of her disappearance have left no doubt in Henrick’s mind that she was murdered. He has spent the last 40 years researching what happened that day, and is convinced that one of his own family members killed her.

Henrick wants Blomkvist to conduct an investigation here on the island, where all his eccentric family members live, and see if he can find any new information leading to the truth about Harriet’s disappearence. His cover story will be to write the Vanger Family History, but the real reason he’s here is to find Harriet’s murderer.

Initially reluctant, Blomkvist is intrigued enough to commit, and sets up shop on the creepy island of Hedeby, where he begins an extensive look into the Vanger family history. What he will come to realize is that the Vangers are one of the most eccentric and dysfunctional families he’s ever come in contact with. And that they are very secretive. These are people who do not want to dig up their past and they don’t want anyone, especially some criminal reporter, digging it up either. The stonewalling forces Blomkvist to do most of his research through archives, which contain more information than he could possibly sift through in a lifetime, which is why he enlists the help of the gifted Lisbeth Salander.

In short, this book is fucking great. I mean there’s been a lot of talk about nothing happening in the opening 200 pages and I agree it takes way too long to get to the plot. I’m wondering if this is because Larsson never had an editor. He was writing these books in a vacuum and I think a lot of that shows, as the last 100 pages are also somewhat insignificant and probably could’ve been cut. But once we get into the central mystery of what happened to Harriet Vanger, this book moves as fast as any I’ve ever read.

Because the history behind the Vanger family is so extensive, and because there are so many members of the family with ties to so many weird and eccentric experiences, there’s an endless amount of fascinating material to explore. After hundreds and hundreds of pages, we begin to realize that Harriet Vanger is just the tip of the iceberg, and that she is actually one in a series of brutal serial murders, which have been carefully covered up over half a century. Uhhh, yeah! Count me in.

I could get into all the great things about this book (as well as some of the sillier things– Lisbeth’s hacking feels a decade late and a microchip short) but in order to keep this review relevant, I wanted to talk about how they’re going to adapt it into a film, because make no mistake, it will be a difficult adaptation.

The book has some qualities that are perfect to build a screenplay around. For example, the nice thing about Larsson droning on in the first 200 and last 100 pages about Wennestrom (a villain whom, it should be noted, we never meet), is that you can lob those parts of the story off and not lose anything, allowing you to adapt a 300 page book as opposed to a 600 page one.

But here’s the thing. I watched the Swedish film adaptation of this, and that’s exactly what they did, is jumped right into Henrick’s offer. I don’t know what it was but something felt off about it, like it was all happening too fast. The book spends a hundred-some pages introducing us to all the varied Vanger family members. Being stuck on that island with that creepy clan builds a necessary feeling of isolation and fear that jumping right in there can’t do. As a result, the Swedish film felt too much like your standard cold case mystery show on TV. The investigation felt too simple and ultimately empty.

Another issue they’ll have to deal with is the timeframe, which takes place over a year in the book. Like I always preach on the site, you want your timeframe to be tight. The ticking clock adds immediacy to your story, which keeps it exciting. But like I mentioned above, a strength of the book is the way it milks its character threads, which all seem mundane initially, but eventually pay off in huge ways. Unfortunately it takes a lot of time to set up those payoffs. When Blomkvist becomes involved in a months-long relationship with Cecilia Vanger, and then is inexplicably dumped and avoided by her, we’re terrified of what she’s capable of, especially as he starts unearthing the truth about Harriet. There’s also just tons of information he has to dig through over the months. The sheer amount of time he puts into this is what makes it so satisfying when he finally makes some progress. To put it plainly, I would not want to be tasked with figuring out what the timeframe is here, as both the short route and the long one have major pros and cons.

But I think where this really becomes a movie, and maybe the one area where the movie can actually improve upon the book – is the relationship between Lisbeth and Blomkvist. Lisbeth is such a fascinating character and one of the driving forces of the novel is to see her finally break out of her protective shell and trust another human being. The novel paints a very complicated relationship between her and Blomkvist that involves an intimate work environment yet a distant personal one. What each character desires and fears always seems to be in direct contrast with one another and this broken timing weaves its way into them like a pair of frantic claws, shoving them together and ripping them apart at will, all the while leaving us confused about what’s ultimately going to happen between them. It’s a great romantic subplot because it’s different and it’s dark and it’s weird and you never have any idea where it’s going to go. Most importantly, we desire to see them end up together, so it’s like this huge bonus storyline that we’re dying to see the conclusion to, which is already sitting on top of the mother of all plot engines, with the search for Harriet’s killer.

I know Fincher is desperately searching for an actress to play Lisbeth Salander and indeed it’s the kind of role that will change an actress’ life. But I just don’t know who you can cast. Everyone’s saying Ellen Page but there’s just no way. She doesn’t have the edge that Salander needs, and yes I’ve seen her in Hard Candy. This character is like that one times 100. You need an actress with some real genuine hatred in her life to pull this off. Maybe they can get Pink or that girl M.I.A. That’s a joke by the way. I offer the question up to you guys. Who do you think should play Lisbeth Salandar?

Anyway, The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo has the potential to finally reinvigorate a 10 year old dead genre, the serial killer flick. There’s more depth in this one novel than there were in 100 serial killer specs I’ve read over the past few years. It’s been a long wait but I think we may finally get that “The next Silence Of The Lambs.”

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[xx] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: I love how the main character here must hide behind a lie for his investigation. Think about it, if Blomkvist was simply asking the Vangers about Harriet’s disappearance, it would be boring – way too straightforward. Instead, he must pretend he’s doing research for the Vanger Family history. This gives every conversation/interview of his an underlying subtext, and therefore keeps the dialogue fresh and unpredictable. For example, he may ask a character about her childhood, but what he really wants to find out is what her childhood friendship with Harriet was like. Trying to steer the conversation a certain way without giving away your true intentions is always going to lead to an interesting scene. It also adds an element of danger to every conversation, because we’re afraid (and he’s afraid) of what might happen if he’s caught. The integration of this tip is story specific, so you can’t just add it to any character. But if it works for your story and your protagonist, definitely consider using it.