Is this the best sci-fi fantasy short story ever written?

Genre: Short Story – Drama/Fantasy

Premise: A young half-Chinese half-American boy struggles to connect with his Chinese mother, who doesn’t speak English.

About: This is a multiple award-winning short story by Ken Liu from his short story collection, “The Paper Menagerie and Other Stories.” You can find it on Amazon. I don’t think the short story can be found anywhere online, unfortunately.

Writer: Ken Liu

Details: Around 4000-5000 words

Ken Liu is really starting to blow up. The team that made 2018’s, “The Arrival,” is turning one of his short stories, “The Message,” about an alien archaeologist who studies extinct civilizations and reunites with a daughter he never knew he had, into a film. AMC is developing a series based on his short stories called Pantheon. You also have Game of Thrones creators David Benioff and D.B. Weiss, adapting Ken Liu’s English translation of the epic sci-fi novel, “The Three Body Problem,” (which won the 2015 Hugo Award for Best Novel, making it the first translated novel to have won the award) for Netflix.

When I started looking into Liu, I learned that his big blow-up moment came upon the release of the short story, The Paper Menagerie. That story achieved something that had never been done before, which is sweep the Hugo, Nebula and World Fantasy writing awards. Everybody says this short story is amazing.

Which has inspired a secondary question as I go into this review. If this is his best work, why isn’t anyone trying to adapt it? There might be an obvious answer to this by the time I finish (some stories just aren’t easy to adapt) or, if not, maybe this article will be the impetus for someone finally buying it.

With that in mind, let’s do this!

(by the way, this story is best enjoyed without knowing anything so I’d suggest reading it first if possible)

Jack is a young boy who lives in Connecticut with his American father and Chinese mother. Jack informs us right away that his father found his mom “in a catalog” for Chinese women looking for American husbands. Even at this young age, Jack considers this weird and something to be ashamed of.

Because his mother was a Chinese peasant, she doesn’t know any English. She tries. But the words never come out right and she becomes embarrassed. Because his father makes him, Jack learns Mandarin, but he resents that his mother isn’t trying harder to learn English, and therefore refuses to speak her native tongue.

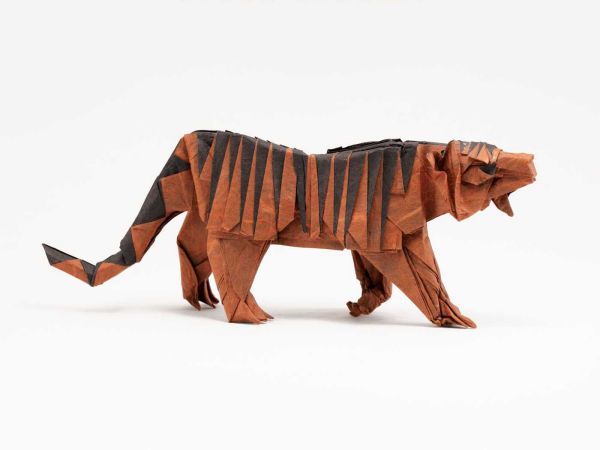

However, Jack’s mother finds another way to communicate with her son. One of the skills she learned from her village was creating special origami animals that are alive!

His family, being poor, couldn’t afford the fancy toys at the time (like all the Star Wars figures) so these origami animals became his toys. He would play with them for hours in his room, never tiring of them.

But when he became a teenager, his resentment for his mother skyrocketed. All this time and she still hadn’t properly learned English, meaning she couldn’t have a conversation with anyone, even her own son. Jack began talking to his mom less and less and even boxed away all her origami animals and threw them in the attic.

During his college application process, his mom gets sick. Her insistence to not be a bother to anyone had meant, by the time she checked in with a doctor, her cancer had spread too far to be treated. Even at this moment, Jack could not muster up any emotion for his mother. Here he was about to pick a college and his mom was still finding a way to mess it up. When he goes out to school in California, his mother dies.

Years later, Jack’s girlfriend finds his old box of origami animals and after she leaves for the day they, once again, come alive. Jack plays with them and it’s just like he was a kid again. Then he spots something on his favorite animal. As he unfolds it, he realize his mother has written a note inside. But it’s in Chinese. So Jack goes to someone who can translate it for him, and the woman reads his mother’s letter to Jack, which tells him the full story of her devastating childhood and how her life was meaningless until he showed up in it.

Okay.

I challenge anyone to read this story and not start bawling from the get-go. This is the saddest story ever. But good sad. “Gets to the heart of broken mother-son relationship” good sad.

I read a lot of screenplays that try to make you cry. Rarely do they achieve it. People think all you need to do to make a reader cry is give someone cancer. Have them die before ever saying “I love you” and people will eat it up. Making people cry is surprisingly difficult. There’s something about the act of trying to make someone cry that keeps them from crying. It’s almost like they know what you’re up to. For emotion to hit on that level, it has to feel like real life. Not like a writer trying to manipulate your emotions.

But one thread that seems to be present in a lot of cry movies is an unresolved family relationship. It could be a man and his wife, a father and daughter, a sister and brother, or, in this case, a mother and son.

I’m not going to pretend like I know the exact code for why this worked because I think nailing an emotionally brilliant story is always going to be a “lightning in a bottle” scenario. But I found it interesting that Liu reversed the typical roles in this kind of story. Instead of the parent being the one who disassociates from the child, it’s the child who pulls away from the parent. And for, whatever reason, that’s more heartbreaking. A child isn’t supposed to despise his mother.

That’s also a big reason why we’re turning the pages. Whenever you set up an unresolved scenario between two characters, we’re naturally going to want that relationship to be mended. It’s painful to walk away from something this emotionally powerful without knowing how it ends. Just by setting this scenario up, you’ve ensured that we’re going to read the full story.

But where Paper Menagerie separates itself from the 10 million other stories that have also tried and failed to make you weep, is this “strange attractor” in the origami animals. The story isn’t just mom and son arguing every day, which is the typical scenario I encounter in similar setups. The mom speaks to Jack through the animals. They become the only way the two communicate. And that adds a special element that elevates the story.

Another small detail was the meanness of Jack. Now, normally, you don’t want your main character to be mean. Once you cross a certain threshold of un-likability for your protagonist, the reader dislikes them and no longer cares about their journey.

What this does is it scares writers into always writing nice protagonists. The problem with that is that there’s nobody on the planet who’s perfect. We’re all flawed. We all have unpopular opinions. Mean thoughts. And if you take that arena away from your hero, you also take away their truth. You are now constructing something that doesn’t exist. And readers pick up on that.

The reason why it works here is because WE UNDERSTAND WHY JACK FEELS THIS WAY. That’s the key to making “mean” protagonists work. As long as we understand where their anger or meanness comes from, or, even better, we can relate to it in some way, then the meanness is going to work.

Jack is lonely. He is half-Chinese in a town where there are no other Chinese kids. Everyone knows his mom was purchased. When friends come over, his mom never speaks because she doesn’t know English. As a kid, this is embarrassing. Cause you have to deal with the effects of that every day. Of course you’re going to have resentment towards your mother. Once you’ve grounded the central story emotions in that reality, you’re golden. Because now we believe what we’re reading to be true and our focus shifts to, “Will this broken bridge ever be mended?”

Finally, I want to talk about the big final letter. The “final letter” scenario is actually something I see quite a bit in screenplays. Everyone thinks they’re being original when they do it but, trust me, it’s not original. And most of these writers fail gloriously with these letters. The reason being that they write something too obvious. “I always loved you. I think you’re going to become an amazing person. I wish we could’ve been closer but I’ve learned with time we will always be together spiritually… blah blah blah.”

This letter hit on some of those things, but it wrapped them around two key choices that elevated the letter beyond your typical “end of movie letter moment.” The first was she told the story of her childhood. Again, most writers are thinking literally: “I need to have mother tell son how she feels.” That’s obvious and rarely works. So to instead talk about her childhood shifts the focus away from her feelings about him and tells us about her. It was unexpected and her background was so detailed and interesting that it was almost like a story in itself we wanted to know the ending to.

The second thing Liu does (spoiler) is that the letter doesn’t end on a happy note. It isn’t one of those, “Go out there and seize the day!” endings. It’s more of a, “I was devastated we could never communicate and I always wished you gave me more of a chance” endings. That simple shift takes this from a perfect wrapped–in-a-bow Hollywood ending to something more realistic, more true to life.

I see now why everyone went nuts for this. It’s almost a perfect story. I don’t think they can turn it into a movie though. It works because its short form allows it to stay hyper-focused on the relevant variables (the mom, the origami animals). Once you extrapolate that and add a bunch of other plot, the concept becomes distilled and the animals don’t make as much sense.

I don’t know. Maybe someone would be able to figure it out. I’m surprised no one’s tried. Like I said earlier, maybe they will now.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[x] genius

What I learned: Ken Liu has an interesting philosophy in how he treats his first draft. He calls it the “Negative First Draft.” Here is his explanation to tor.com. – I usually start with what I call the negative-first draft. This is the draft where I’m just getting the story down on the page. There are continuity errors, the emotional conflict is a mess, characters are inconsistent, etc. etc. I don’t care. I just need to get the mess in my head down on the page and figure it out.The editing pass to go from the negative-first draft to the zeroth draft is where I focus on the emotional core of the story. I try to figure out what is the core of the story, and pare away all that’s irrelevant. I still don’t care much about the plot and other issues at this stage.

The pass to go from zeroth to first draft is where the “magic” happens — this is where the plot is sorted out, characters are defined, thematic echoes and parallels sharpened, etc. etc. This is basically my favorite stage because now that the emotional core is in place, I can focus on building the narrative machine around it.

In the newsletter I just put out, I talked about mindset shifts (“Don’t be Park Exercise Douche Guy!”). Mindset shifts are important in all areas of your life. But they’re especially important for artists. Unlike traditional business structures where there’s a clear path to move from A to B to C to D to vice-president, art is something where you disappear into a dark room then come out with your creation and get politely told by a lot of people, “No thank you.”

This is the main reason why so many people fail in Hollywood. Hearing the nos over and over again can become debilitating and even reach levels of PTSD for some. But it’s even worse for writers. For a writer, you’ll work on something for a really long time, unveil it to a group of individuals, they all tell you it’s “okay,” or “not bad” or even “good,” but their actions speak louder than their words because they didn’t like it enough to want to do anything with it. So now you’re back to square one.

So you go back into your cave and you write a new script with the additional knowledge you’ve gained from writing the last one and then emerge once more 6-12 months later and maybe you encounter a bit more enthusiasm than last time but the answer is still the same. “Not something I can do anything with. Sorry.” Imagine going through that three times, four times, five times, a dozen times! That’s psychologically debilitating for most people and they don’t want to keep subjecting themselves to it. It’s one of the reasons I think you have to be crazy to be an artist. Or, at the very least, a masochist.

The question, then, is, “How do we stop that cycle?” “How do we overcome that constant rejection and succeed?” I know the answer to this. You probably do, too. But there are psychological factors going on that are preventing you from realizing it.

Most writers put so much emphasis on writing the script itself that they forget it doesn’t matter how good of a job you do if people don’t like your concept. So you’re spending all this time researching, creating, and beta-testing this lipstick that you think is going to change the world. But when it comes time to sell it, you’re putting it on a pig.

This is a roundabout way of me reminding you that concept is king. It isn’t everything. But it kind of is. Of course character and plot and dialogue and actually knowing how to tell a good story are massively important. But if people don’t like your idea, they won’t ever get to your great storytelling. Even the ones who do read your script are likely doing so as a favor. They know you so they’re willing to give anything you write a chance. But they pretty much know, before they’ve opened the script, that they’re not going to like it. Because the concept is lame.

Look no further than the script I reviewed in the newsletter – Unknown Phenomenon. Now it just so happens I went into that script cold. So I didn’t know what it was about. But had you told me ahead of time it was about a mysterious small sphere that misbehaved and ruined a family’s lawn – I would never have read it. Or, if I had to read it for work or because someone needed me to, I would’ve mentally decided that there was a 99.999% chance the script was going to be bad going into it. Even if they would’ve miraculously managed to write a good script off that idea, the odds were I would’ve mentally checked out long before it got good. That’s the kind of effect a bad idea has on a reader. It can frame their opinion of the script before they’ve read a word.

Unfortunately, there’s no universal way to identify a bad concept. Just like everything in art, movie concepts are subjective. But you shouldn’t use this as cover for going with a low-concept idea. You shouldn’t be saying to yourself, “It doesn’t matter that Jake said my idea isn’t big enough to build an entire feature around. Ideas are subjective.” Instead, you should assume the reality of the business – which is that the large majority of script ideas are bad – and therefore push yourself to make sure you don’t end up in that majority.

I’m going to provide you with a hack on how to achieve this. I call it the “DO ME A FAVOR” test. Early on in my writing career, I tried to get people to read this road trip romance I’d written. At the time, I was so in salesman mode that I wasn’t able to pick up on some social cues I was getting that would’ve helped me realize it was a less than stellar idea. But later on, when I was able to get some distance from the experience, I noticed that over the course of pitching the script, my tone and demeanor were very much, “Please do me this favor and read my script.”

Now when you’re a nobody (and especially a beginner), you’re going to be in this situation regardless of what you write. Of course anybody in the industry will be doing you a favor by reading your script. But that’s not what I’m talking about here. What was happening with me was that I knew, deep down, that my script wasn’t commercial. It wasn’t high concept. It didn’t even have a clever ironic twist that smaller scripts need to stand out. It was just a normal unoriginal road trip story. And for something like that to get made, it was going to take people moving mountains. So my mindset when I was pitching it to people reflected that. Even when I talked up a big game, my subconscious was saying the opposite – Please do me a favor and read this. Please give this script a shot. I need your help to get this script made.

Now that I’ve had some distance from these attempts to sell scripts, I’ve realized that, at the concept stage, I should’ve been conceiving of script ideas that did the opposite. I should’ve been writing ideas that, when it came time to go out there and get people to read it, I WAS DOING THEM A FAVOR.

I want you to think about that for a second. Because it’s REALLY important. When you look at your current screenplay, is it an idea that’ll require you to ask others to DO YOU A FAVOR? Or is it a script where you’re going to make somebody the luckiest person in the world to have discovered your script first? That’s your concept-creation hack. You want to write ideas that, later on, when you give your script to people, YOU ARE DOING THEM A FAVOR. Because the first person that buys this thing is going to be rich and successful.

That doesn’t mean, by the way, that you should say that to people, lol. “I’M DOING YOU A FAVOR HERE, PAL.” But it should exist in your body language, the confidence in which you talk about it, and in your overall excitement for the script. You know you’ve got a “DOING THEM A FAVOR” concept when all those things happen naturally. You don’t have to force them at all.

This is hard for a lot of writers because when you spend a lot of time with anything – especially a script – you learn all of its flaws. So you’re afraid to oversell it. Which is all the more reason to think hard about what you’re going to write next. Cause you already know the script is going to beat you down during the writing process. They all do. That means you have to start with the strongest piece of oak you can get your hands on. That way, you know, when you call and e-mail and meet the people you’re going to give your script to – you’re going to remember that the idea you chose was one that was going to help others. Not one that was only going to help you after you somehow conned a bunch of people into getting your movie made.

Since I know the concept world is such a subjective one, I’m going to give you some examples of “PLEASE DO ME THIS FAVOR” and “I’M DOING YOU A FAVOR” screenplays. Keep in mind that it’s hard to give examples of bad movie ideas because they have to be successful enough that you’ve heard of the example. So remember that in many of these cases, the bad ideas only got made because of factors such as the writer was also an established director and therefore could’ve gotten financing for any idea they had. You must think of these ideas in the context of YOU pitching them, an unknown writer. Likewise, there are going to be bad movies that get the label “I’M DOING YOU A FAVOR.” That’s actually strengthening my point, not weakening it. It reinforces that concept is everything. Producers know that a good concept can withstand bad execution whereas a weak concept has to have an almost perfect execution. Okay, here we go…

WAIT! I have an idea. Before you see the examples, I’m going to give you all the movies. See if you can guess what they’re going to be before I tell you (PLEASE DO ME THIS FAVOR or I’M DOING YOU A FAVOR). If you get them all right, it means you have a good eye for concept creation. Bonus points for whoever lists their answers in the comments BEFORE they see if they’re right. Okay, here are the movies: Moonlight, The Invisible Man, Eighth Grade, Columbus, Gemini Man, A Quiet Place, The Kind of Staten Island, Seven, Honey Boy, Cabin in the Woods, O Brother Where Art Though, and Fantasy Island.

All right…

Now onto the answers!

Moonlight – PLEASE DO ME THIS FAVOR

The Invisible Man – I’M DOING YOU A FAVOR

Eighth Grade – PLEASE DO ME THIS FAVOR

Columbus – PLEASE DO ME THIS FAVOR

Gemini Man – I’M DOING YOU A FAVOR

A Quiet Place – I’M DOING YOU A GIGANTIC FAVOR

The King of Staten Island – PLEASE DO ME THIS FAVOR

Seven – I’M DOING YOU A HUGE FAVOR

Honey Boy – I’M BEGGING YOU TO DO ME THIS FAVOR

Cabin in the Woods – I’M DOING YOU A FAVOR

O Brother Where Art Though – I WILL GIVE YOU MY FIRSTBORN CHILD IF YOU DO ME THIS FAVOR

Fantasy Island – I’M DOING YOU A FAVOR

So, what about concepts that don’t fit nicely into either of these categories, but rather land in the middle? You’re not quite doing them a favor but you’re not doing yourself any favors either. “The Rental.” “Booksmart.” “The Secret Life of Walter Mitty.” “The Tax Collector.” “Vivarium.” Are these ideas okay? Yes, they’re okay. But you have to realize that the further away you stray from a clear “I’M DOING YOU A FAVOR” concept, the harder your life is going to be when you finish the script. If you’re a hustler and like trying to get people to read your script, you can afford to write something with a little less zing on the concept. But if you’re like most writers and want the writing to do the talking, I would stay away from these middle class concepts. The execution almost has to be as great as the execution on a weak concept to get people interested.

Just remember, when you’re trying to decide which idea to write – close your eyes and put yourself across from the person you most want to pitch your script to when it’s done six months from now. Does it feel like you’re asking them for a favor or does it feel like you’re giving them the opportunity of a lifetime? If it’s the former, you probably want to go with another idea.

Carson does feature screenplay consultations, TV Pilot Consultations, and logline consultations. Logline consultations go for $25 a piece or $40 for unlimited tweaking. You get a 1-10 rating, a 200-word evaluation, and a rewrite of the logline. They’re extremely popular so if you haven’t tried one out yet, I encourage you to give it a shot. If you’re interested in any consultation package, e-mail Carsonreeves1@gmail.com with the subject line: CONSULTATION. Don’t start writing a script or sending a script out blind. Let Scriptshadow help you get it in shape first!

CHECK YOUR INBOXES!

Alert your SPAM folders and declassify your PROMOTIONS folders. The Scriptshadow Newsletter should be there.

Script review of the script that’s supposed to start the alien version of the Conjuring Universe. Thoughts on Emmy wins and losses. Big motivational speech about how you should approach your screenwriting career for maximum success potential. I go over all the fun projects that have been announced this month. Update on The Last Great Screenplay Contest. Go into your e-mail and get it!

If you want to read my newsletter, you have to sign up. So if you’re not on the mailing list, e-mail me at carsonreeves1@gmail.com with the subject line, “NEWSLETTER!” and I’ll send it to you.

p.s. For those of you who keep signing up but don’t receive the newsletter, try sending me another e-mail address. E-mailing programs are notoriously quirky and there may be several reasons why your e-mail address/server is rejecting the newsletter. One of which is your server is bad and needs to be spanked.

Genre: Thriller/Drama

Premise: A little girl living in the wilderness with her parents has her life turned upside-down when a mysterious man shows up on something she’s never seen before – a snowmobile.

About: An interesting project today, guys. First off, we have a script by Mark L. Smith (and his wife!). Smith, the writer of Leo DiCaprio’s The Revenant, is one of the most coveted writers in town. The Smiths are adapting a novel that’s said to be the next “Room,” which, for those of you who remember, was my favorite movie of 2015. Also, this is one of the rare novels on Amazon that has over 1000 reviews and a 4 and 1/2 star rating or higher. So it’s supposed to be really good.

Writer: Elle Smith and Mark L Smith (based on the novel by Karen Dionne)

Details: 106 pages

There are so many common story scenarios that it’s easy to get discouraged. Why try to write another version of an idea when it’s been done so many times already? Luckily, there’s an answer to that. You simply look for a new angle.

Take a young girl being kidnapped. That’s as old a scenario as it gets. So how can you approach that angle differently? Well, you can approach it via a detective looking for the young girl. You can turn the missing girl into a cold case, so the detective is looking for her 30 years after she went missing. You can tell the story from the missing girl’s perspective. You can tell the story from the kidnapper’s perspective.

In the book, “Room,” (not the movie), a little boy tells the story about living in this room for his whole life with his mother, who, it turns out, was kidnapped by the man who’s now holding her captive here. He, the boy, happens to be the offspring of his mother and that man. That’s about as unique an angle as you can come up with for a kidnapping story.

Which brings to The Marsh King’s Daughter, a story that takes the same initial angle as Room but switches a few key variables. 12 year old Helena Holbrook lives in the middle of Northern Michigan in a settler’s cabin with her father, Jacob, and her mother. We’re initially led to believe that this is the 1800s. But then, after hunting with her father, Helena stumbles across a PEOPLE MAGAZINE with Princess Di on the cover. It turns out we’re a little closer to modern day than we thought.

We immediately get the sense that Helena’s mom isn’t the happiest person. While Jacob can’t wait to go out with his daughter and teach her about survival every day, Helena’s mom just stands around and scowls a lot. When Jacob heads out for a two day trip to get supplies, a lost man on a snowmobile zooms up to the house. Both Helena and her mom stare at it in shock. Helena has never seen a snowmobile in her life. She’s never seen any type of vehicle. Then, inexplicably, the mom charges the man and starts screaming, “Hurry! Get us out of here before he comes back!”

What we’re about to learn is that Jacob kidnapped the mom when she was 13, then brought her up here and had a child – Helena. This man is a kidnapping rapist. Which means Helena’s entire life has been a lie. No time to worry about that though as a hole appears in the snowmobiler’s head. Yup, he’s dead. The dad is sniping at them at getting closer. Helena’s mom grabs her and zooms off on the snowmobile. Helena wakes up in a modern day police precinct a few hours later. There she’s told the truth about her life, a truth she can’t accept.

That’s the end of the first act and we cut to modern day, where Helena is now married to a man named Stephen. They have a little girl of their own, Marigold, and live in a beautiful Ann Arbor, Michigan house. But their marriage is on the rocks due to the fact that Helena is a psychological mess, unable to trust anyone or anything. Compounding this daily trauma, she’s kept the truth of her former life a secret from her family.

Then the unthinkable happens. Jacob escapes from prison. It doesn’t take long for the FBI and media to descend upon Helena, as they suspect she’ll be the first one he contacts. Stephen feels like he’s been hit with an atom bomb as he realizes everything he thought he knew about his wife is a lie. All of a sudden, the family must prepare for the possibility that Jacob will come for them.

Helena is going insane. Even after they find a burned body in the woods they say is, 100%, Jacob’s dead body, she knows he’s still out there. So she heads to a secret waterfall that they used to talk about all the time, a place he said she could always find him. And he didn’t lie. She shows up and there he is. The question is, what does he want from her? Or, more appropriately, what does he plan to do to her?

Like I said, The Marsh King’s daughter takes a different angle from what we traditionally see in kidnapping movies. The kidnapping has already taken place well before the story started. We get a great early twist when the snowmobile man shows up and is subsequently killed. Talk about grabbing the reader. As a result, the first act is nearly perfect.

But then the story decides it’s going to be a PTSD movie based on how kidnapping affects the victim after they’ve grown up. I like that the writers approach yet another kidnapping movie from a fresh angle. But let’s get real here. Living a safe life with years of distance between you and your kidnapping is never going to be as intense as being inside the kidnapping story as it’s happening.

I think the writers sensed this and were looking for as many ways as possible to keep that setup interesting. First we get the prison escape. Which does add a more exciting element than had their not been an escape. Then we move into Michael Myers territory where Helena starts to think she sees Jacob around town.

The problem with that is that it was explicitly set up that Jacob loved Helena more than anything. He would never hurt her. So when I see Michael Myers in the downtown crowd of a Halloween party, I know my heroine is going to be in a life or death struggle within the next few scenes, seeing Jacob in a crowd means… what? He’s going to come over and say hi? They’re trying to present his presence as dangerous when it isn’t.

What this all means is that The Marsh King’s Daughter is more of a drama than a thriller. An if you’re looking at it through that lens, it does a solid job. I liked exploring the psychological trauma something like this would do to a person. I watched that Amanda Knox documentary on Netflix and there is nothing more haunting than that woman’s eyes. What she went through in Italy when she was accused of murder and subsequently went to prison – that still informs every single decision she makes during the day. And we get the sense that Helena is a similar position. How can she trust anyone when the one person she was supposed to able to trust turned out to be a monster?

But, in the end, this script struggles with structural problems. The best stuff, by far, occurs in the first quarter of the story. That cannot be the case. A script must get better as it goes on. It can never be NOT AS good as what preceded it. This happens whenever you create a narrative that has characters waiting for the plot to give them permission to act. This whole movie is built around Helena waiting for the plot to tell her what to do. Wait once the dad escapes prison. Wait to see if the DNA on the burned body matches her dad. Wait for the media and FBI to come to her. 75% of Helena’s journey is waiting. Like I always say, it’s not impossible to make “waiting around narratives” work. But it sure as heck isn’t easy.

Despite that, the script has a great first act and a good last act. And it’s written well. For those reasons, I think it’s worth reading.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Three variables you can use to find new angles on old ideas are PERSPECTIVE, TIME, and GENRE. Perspective refers to which character’s point of view you follow the story from. I just talked bout this in a recent review. The writer wrote a story about a teenage boy losing his virginity from the point of view of the condom. Time refers to when you cover the event. Today’s review was about the effects of a kidnapping 20 years later. Also, “time” is a shifting variable. Nobody says you can only cover one time period. Marsh King covers two. The kidnapping when it was going on and the kidnapping 20 years later. Finally, genre allows you to instantly change an idea. Marsh King is a different film if we make the dad a vampire. It’s also a different film if we make Helena a stand-up comedian who uses her unique kidnapping past to frame her stand-up routine (“So you guys thought you had a bad childhood cause Johnny didn’t ask you to prom? Check this out.”)… The important thing here is to never give us the most generic version of the idea. That’s usually the one that nobody’s going to care about. Playing with the variables is the key to making your idea stand out.

Genre: Sci-Fi

Premise: In a post-apocalyptic future, the passengers on a maglev train traveling from Los Angeles to London get more than they bargained for when an alien creature gets loose.

About: Giddy with excitement. I haven’t read the script yet. All I heard was aliens on a train and I was in. Jim Uhls (Fight Club) wrote the original spec script of this idea for Ridley Scott. Scott developed it for a while but eventually left and Roland Emmerich would come on. This draft, by Steven de Souza, was supposedly a bit of a departure from Uhls’ version.

Writer: Steven E. De Souza

Details: 133 pages (1990 draft)

Snakes on a Plane? PFFFT!

Please.

That is so 2003.

Try ALIENS ON A TRAIN!

Yeah, baby. Now you’re talking bout movies that get the adrenaline pumping. Me? Love aliens. Me? Kinda love trains. What do you get when you add love and kinda love? That’s more than double the love. Love and three-quarters. Think about the person you’ve fallen in love with most in your life. This is more than that. Well, it’s not more than that yet. I haven’t read the script. I’m about to. But I’m fully expecting that there’s no way I will not love and three-quarters this script. Its pedigree precedes it.

I mean how did this not get made?

There’s aliens!

On a train!

Not a steamboat.

Not a stagecoach.

Granted, those would be awesome too. But they’re nowhere near as cool as aliens on a train.

It’s the future: Los Angeles, 2015. Okay, it’s the future *for this script*. Obviously, the writers didn’t budget for a time machine to come to 2015 and realize that we weren’t yet apocalyptic. I mean do your homework, guys. Come on! Anyway, things are bad in their version of 2015. For starters, most of Los Angeles is covered in desert. On top of that, there’s barely any ozone left. So lots of sunburn and breathing issues.

But there is still a society and still a world economy. One of the most promising industries is maglev train travel. The world government outlawed planes due to ozone issues so trains have become the only way to travel long distances. One of those trains, the big maiden voyage from Los Angeles to London, is leaving today.

In the spirit of an Agatha Christie novel, we meet the many passengers who will be trekking on the luxurious train. There’s Hedda, who’s escorting her fertile 15 year old granddaughter, Lisa (fertility is a rarity in this future world). There’s suspicious doctors Scanlon and Ruby. There’s the rich a-hole, Reggie. There’s the train manager, always prickly Sari. And then there’s Russ Prine, who secretly works for the company and is taking the trip undercover to make sure everyone who works on the train is doing a good job.

Once the train gets going, we cut to Scanlon and Ruby’s room where we realize these two are not doctors. They’re escorting a big tube thing that happens to have an alien in it. Their only job is to inject it with some pain juice (that’s the only way I understood it) which would keep it from doing anything naughty.

Meanwhile, we have a little comedic subplot of Prine trying to make Sari’s life a living hell. He asks for numerous things he knows she doesn’t have (a certain meal cooked a certain way, for example) to see if she remains professional. Spoiler alert: she doesn’t.

As the conflict between them grows, Scanlon and Ruby forget to inject the pain juice and this tentacled scary alien creature breaks out of its coffin and begins killing people before disappearing into the train’s innards. Sari and Prine run into the creature, surviving it, and realize they need to do something FAST. Except they can’t because the train is currently in some section of the US that has no air due to ozone issues. Which means they’re going to have to find and kill this thing while the train is on the move.

Sari tells all the passengers to move up to the first two cars, giving her, Prine, and a handful of other volunteers, the rest of the cars to find and trap this thing. Of course, they have no idea what this thing is and therefore underestimate it. And when it damages the brakes, the train loses all ability to slow down. Which means they’re barreling towards London at 1200 miles per hour with no way to stop. What’s going to happen??? How are they going to get out of this??? ALIEN ON A TRAIN!

Just like I expected, this was a wild read.

It’s got something going on. I always wanted to turn the page. But it’s messy and my guess is that’s because it’s over-developed.

Over-development is a word of the past. It infamously resulted in a lot of bad films in the 80s and 90s. Nowadays, places like Netflix laugh at development. “Why develop something when you can just greenlight it,” is their motto. As a result, we get paper-thin movies like Project Power.

But back then they had the opposite problem. They’d hire writer after writer and have all of them doing endless drafts. Which resulted in one of three scenarios. The best scenario was that they eliminated all the script’s weaknesses, the movie got made, and it turned out great. Think Good Will Hunting or Gladiator.

The second scenario was that each successive rewrite would beat the originality out of the screenplay, giving us something with zero unique characteristics that was utterly bland. Think 1998’s Godzilla.

The final scenario is what’s happened here. With so many writers and drafts packing so many things into the script, the elements start to impede upon each other, competing for plot real estate. Think about it. There’s two movies in this script. There’s the maiden voyage of some post-apocalyptic intercontinental train (think the train version of Titanic). And then there’s an alien that gets loose on a train. I’m not convinced these two ideas can share the same movie.

Usually, when you have a cool concept, you want to treat it like Michael Jordan. Give it the ball and tell everybody else on the court to get the f*%# out of the way (as coach Doug Collins once famously said). This is not that. This alien is not only secondary but it doesn’t fit into the mythology. You’ve established we live in this giant desert now. When the heck did aliens show up?

Now, as it so happens (spoiler), it turns out this isn’t an “aliens on a train” script. It’s a “monster on a train” script. The creature is man-made. I get why they did this. BUT IT’S NO ALIENS ON A TRAIN! And that’s why I showed up. To see aliens. On a train. Ripping organs out of human passengers.

I bet the original idea here by Jim Uhls had aliens. Somewhere along the way, it became a monster. And this is what happens in development all the time. It’s one of the hardest things to manage for a writer, producer, studio, or whoever. Stories take on a life of their own. They want to do things you didn’t originally expect. So you have to decide if you’re going to give in to the new direction or stick to your guns.

I’m guessing that they couldn’t figure out why the aliens were on the train or why they would go around killing people so they came up with this storyline that better connected with the mythology (the creature, it turns out, was man-made to replenish the ozone).

I dunno.

I’m torn on which is the right thing to do. One part of me says, stick with the original cool idea you had. The further away you go from the original idea, the further away you go from the coolness. But then you hear stories like M. Night’s, whose original idea for The Sixth Sense was a psychiatrist helping a kid who painted paintings of things that hadn’t happened yet. The kid didn’t see ghosts. Bruce Willis was not a ghost. M. Night followed the story through multiple drafts before incorporating those two things. And that ended with, arguably, the most successful spec sale of all time.

But.

But.

But.

Aliens on a train!

I wanted aliens on a train!

Can someone contact Jim Uhls and ask him for the original spec script where we had aliens on a train? Please. That’s what I want to read.

Despite all that, this is still wacky in a fun way so I recommend it. Especially if you loved the high concept era of spec scripts.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Steven de Souza has some wisdom for those wondering why some things get made and others don’t: “Movies get made not because the script is great, but because somebody likes the script at that point.”