Today we’re covering a movie that would NEVER get made today. But, not to worry, I think it’s only a matter of time before the pendulum swings back to sanity with this cancel culture stuff. Comedy is at its best when it’s pushing the envelope. And today’s script shows us just how hilarious pushing the envelope can be. If you’ve never seen Tropic Thunder, it’s about a group of actors shooting a war movie who, unknowingly, find themselves in an actual war.

1) Easy comedy concepts are staring you in the face! – Further proof that one of the easiest ways to come up with a funny movie idea is to take a serious movie and turn it into a comedy. “What if we made Platoon a comedy?” could’ve easily been the starting point for this concept.

2) Character intros that tell you exactly who your characters are – Introduce your characters in a way that tells us exactly who they are. Comedies are about LAUGHS so you don’t have 20 minutes to meticulously set a character up. You gotta do it quickly so you can get to the funnies. To this day, no comedy has set up its characters better and faster than Tropic Thunder. The idea to introduce each character via trailers of the biggest movie they starred in (Tugg Speedman in his goofy blockbuster franchise, Scorcher. Kirk Lazarus in his Oscar bait gay priest movie, Satan’s Alley. And Jeff Portnoy’s awful ‘plays all the characters in the movie’ Fatties franchise) immediately told us who these characters were.

3) Every situation is an opportunity for a character to reinforce his funniest trait – The joke with Kirk Lazarus (Robert Downey Jr.) is that he’s always trying to win an Oscar with every line he delivers. So when Tropic Thunder’s director gets blown up by a land mine, the five actors look around at each other, unsure if what just happened was real or fake. Tugg Speedman (Ben Stiller) declares, “This is nothing, guys. It’s all part of the game. It’s what he was talking about with all that ‘Playing God’ stuff.” Kirk Lazarus looks off at nothing and, in the most serious voice you can possibly imagine, replies, “He ain’t playing God…. He’s being judged by him.” Lazarus dutifully delivers Oscar-baiting lines even when their director just got blown to bits.

4) Death is hilarious – In every other genre, death is serious. But comedy is the one time people are willing to laugh at death. So take advantage of that. When the director is blown up by the mine, Tugg Speedman is convinced it’s fake. He assures the guys, “I’ve been in a lot of special effects movies. I think I know what a prosthetic head looks like.” Tugg picks up the director’s head and starts playing with it, going to every extreme to prove it’s fake, even tasting the blood to prove it’s corn syrup. Death is funny guys. Lean into it!

5) Never let a busy plot get in the way of your comedy script – I have seen busy plots destroy comedies. Busy plots lead to lots of exposition. Exposition is hard to make funny. Tropic Thunder doesn’t do a great job of this. There are quite a few scenes where the characters have to stop and remind themselves where they’re going and what their current goal is. There’s a boring scene, for example, where they realize they mis-followed the map and are now lost and they have to figure out where to go next. Too many of these scenes can disrupt the rhythm of your comedy, which is when readers start losing interest. Try to keep your plot as light as possible in a comedy. And if you are adding big plot points, make sure they’re funny!

6) Ultra-serious guy is funny! – A standby character that’s almost always funny is the SUPER EXTREMELY SERIOUS GUY. This character always works because of the irony. What’s the polar opposite of funny? Serious. So when you dial that up to 11 in a comedy, it rarely misfires. In Tropic Thunder, that character is Nick Nolte’s Four Leaf Tayback, the real life veteran who wrote the book the movie is based on. Nolte steals many of the scenes he’s in with his deadly serious delivery. When explosions expert Cody (Danny McBride) informs Four Leaf he’s his biggest fan and tries to chum it up by asking, “That’s a pretty cool sidearm you got there. What is it?” Four Leaf replies… “I don’t know what it’s called. (Long pause) I just know the sound it makes (long pause) when it takes a man’s life.”

7) Learning proper structure puts you in rare air in the comedy genre! – I’ll let co-writer Justin Thereoux explain why: “Me and Ben had written a bunch of scenes. Basically, we beat out the characters, and had sixty pages of loose stuff that we were trying to organize. But Ben was working and I was working, so we called Etan (Cohen), and he came in, gave us an outline, and wrote a short draft. Then me and Etan worked together in L.A. I came out from New York, and we hung out for an intense five days where we went through the script and recalibrated the tone. Then he went off, and me and Ben took the script and [finished it].” Comedy people actually aren’t very good with structure I’ve found. They’re good at jokes. They’re good at coming up with funny situations. But I can’t tell you how many comedies I read where the structure is a mess. Heck, even yesterday’s script had structure problems. If you’re funny AND you’re good with structure? You’re the total package, baby.

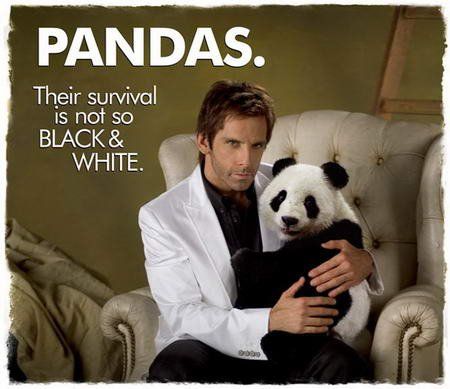

8) To give the audience what they ‘expect’ in a comedy is the equivalent of script suicide – You want to avoid the expected in every genre, of course. But you especially want to avoid it in comedy because the best punchlines are often unexpected. Tugg Speedman is alone in the jungle at night when he’s attacked by a large animal. Blinded and desperate, Speedman grabs his knife and releases his inner rage, battling the animal, stabbing it dozens of times. When he finally kills it and is able to see what it is, what do you think he finds? A bear? A jaguar? A tiger? No. It’s a panda bear. Tugg killed a cute cuddly panda bear.

9) Comedies are upside-down world – In comedy, insignificant things are often extremely important and extremely important things are often insignificant. For example, one of the major running jokes in Tropic Thunder is Tugg Speedman’s agent (played by Matthew McConaughey) becoming obsessed over a minor clause in Speedman’s contract – he gets to have Tivo on location – not being met. McConaughey’s entire storyline is built around him making sure that somebody corrects this mistake. It’s hilarious because, in the grand scheme of what’s happening, it is beyond insignificant.

10) Likability of your main character matters a lot in comedy – In a Collider interview, Ben Stiller (who directed and co-wrote the film) was asked if he was worried about Tugg Speedman being unlikable in the script. This was his answer, “Sure, there were aspects of my character in the beginning that I put on the DVD, the extended cut because at that point, who cares if we’re likable or not? (Laughs.) Um, but that was one of the things, because my character is trying to adopt a baby and there’s a joke where he said, ‘I feel like all the good ones are taken.’ And it was always funny out of context, but in the movie it always felt like people thought, ‘Ugh, I don’t want to watch that guy for the rest of the movie.’ (Laughs.) So, I cut that from the movie.” While it’s tempting to have your hero say whatever jokes pop up in that head of yours, you need to be more calculated. Sometimes an early hateful or off-color joke can solidify a character as “unlikable” in the audience’s mind. So be mindful of that. Also, when you have people read your comedy, one of the first things you should ask them is, “Did you like my main character?” If they didn’t, ask why, and try to correct it.

The giant million dollar spec sale that was supposed to star Chris Pratt and, then wife, Anna Faris

Genre: Comedy

Premise: An uptight couple go on a tropical vacation where they befriend a crazy couple who likes them so much that they show up uninvited at their wedding six months later.

About: This script sold in 2014 for a 7 figure check with Chris Pratt and Anna Faris attached and was supposed to be one of the biggest movies of 2015. Poor production house that bought this. It’s not often that you have a divorce derail your movie. But they picked up the pieces and still managed to put a movie together, with John Cena taking Pratt’s role. The movie’s already been shot and is now in post-production. It should be released later this year.

Writers: Tom & Tim Mullen

Details: 2013 draft (I’m assuming they rewrote a lot of this after Pratt left the project)

There’s always speculation around why a script sold for a lot of money. Is it because the script is amazing and unlike anything else out there? Or is it the actor you’ve attached that’s really bringing in the dough? Or, third option, is the script so good that it was able to nab the big actor, which furthermore, justified why it sold for so much money? The only people who know are the ones who bought the script. The rest of us can only speculate. But that’s what’s so fun about Scriptshadow. I can usually rule in favor of if it was the script. Which is what I’m hoping to do today.

Mark Hickman and his girlfriend, Emily Conway, are vacationing in Los Cabos for the week. What Emily doesn’t know is that Mark is planning to propose to her. That’s the good news. The bad news is that Mark knows, once he makes this move, he’s going to be a corporate stooge for the rest of his life, abandoning his dream of starting a tech company.

Right as Mark is about to propose at lunch, Ron Massey and his wife, Kyla, show up. Ron Massey is basically Danny McBride, and Kyla is every hot white trash girl you’ve ever met mixed into one. Here’s a teary-eyed Ron as he looks out at the ocean for the first time: “I’m fine. The ocean gets me, you know? We used to live in her. And then millions of years ago, one of us was brave enough to crawl out on land. Like a shrimpy little astronaut. Now here we are. Free. Upright. I can’t help but think the ocean is damn proud of us.”

Ron and Kyla act as the devil on Mark and Emily’s shoulders, getting them to do shots, then coke, then hallucinogens, then everything else you can imagine. Ron and Kyla even inspire Mark and Emily to get married right there on the island. And they do! But that’s not the culmination of their vacation by any means. Their one week frenzy ends with a drunken foursome! As far as Mark knows, everybody in that foursome stayed on their sides. But he’s about to find out that that may not be the case.

That’s because six months later, Mark and Emily are back to their stiff lame selves. They’re getting married on Emily’s rich dad’s ranch. And who should show up to the festivities? Ron and Kayla! The two were riding by and read in the local paper that Mark and Emily were getting married (again) and how could they not come to their best friends’ wedding?? Oh, and they’re carrying a surprise. Kyla is pregnant. Exactly SIX MONTHS pregnant

Mark, of course, freaks out. If anybody at this upscale party even gets a whiff of Crazy Ron, they’re going to go apeshit. So Mark puts it upon himself to babysit Ron the whole time, keeping him away from the main activities. But that plan goes south when Ron forces Mark to do mushrooms with him. Within four hours, Mark finds himself in front of the entire wedding party rolling in the grass without any pants or underwear on.

As Mark and Emily do damage control, they realize that Ron and Kyla aren’t going away any time soon, which means they’re going to have to manage them the entire wedding procession, a job that becomes a lot more difficult once Mark starts having flashbacks of repressed memories from their Los Cabos vacation – specifically that there was some extracurricular activity going on, and that he may have had sex with Kyla.

Ahhhhh!!!

This one started out so strong!

I loved the first 20 pages, specifically how the writers structured it.

A guy is vacationing with his girlfriend who he’s going to propose to, and the writers do what I told you guys to do Monday – they throw a bunch of obstacles at the hero to prevent him from achieving his objective.

First, Ron and Kyla introduce themselves at lunch right before Mark can propose to Emily. Then Ron and Kyla ask if they can switch tables with Mark and Kyla cause they need to use the outlet next to their table to charge their phone. Then, when the waiter comes with the engagement ring, he of course delivers it to the table he’s been told to deliver it to, which is the one Mark and Emily *used* to be at, forcing Mark into a 4-alarm fire to prevent Emily from realizing what’s going on. This whole sequence was really well crafted.

Everything was set for a fun movie about a couple who has a crazy night out on vacation with another couple, and then the other couple won’t leave them alone for the rest of the vacation. Comedy gold!

So when we started sprinting through a rest-of-the-vacation montage in the first act, I got worried. However, they redeemed themselves with a great climax (literally), which left the potential for some fun story threads later on.

But when we jump six months later with Mark and Emily getting married (officially) and Ron and Kyla showing up at their wedding unannounced, I let out a big ‘uh oh.’ Look, I’m lenient when it comes to logic issues in comedies. But the one area you can’t mess around is the set up. The set up SETS UP the rest of the story. So if it’s shaky, the rest of the movie is shaky.

I couldn’t buy into Ron and Emily showing up unannounced. I know they’re clueless but if there’s a universal rule that everybody knows, it’s not to show up at a wedding you haven’t been invited to. So that bothered me.

However, I was able to get over it, and the writers did bring in a fun plot development I was curious about. Kyla is six months pregnant. It’s been six months since their vacation. Could it be that Mark is the father of Kyla’s child?

But then things really go off the rails. It becomes the “Ron Show.” And while Ron is the funniest character in the movie, he didn’t work as well in the wedding as he did the vacation. One of my big beliefs is that you lean into what’s unique about your premise. That’s how you make yourself different from all the other movies. How many movies have taken place during weddings? Like a billion. Your script is even titled, “Vacation Friends.” Why not just keep this whole movie on the vacation? If you would’ve done that, you would’ve had the movie “The Wrong Missy” should’ve been.

Also, comedy works best when the thing that’s at stake truly means something to your characters. If the characters don’t really give a shit, any comedy you try and build around that storyline won’t work. For example, one of the ongoing threads in Vacation Friends is that Mark and Emily are pretending like this wedding they’re doing isn’t real so as to not upset Ron and Kayla, who believe that the wedding they had back on the island was the real one.

But who cares if they find out? What’s going to happen? Ron’s going to say, “Wait, this wedding is real?” “Yes.” “Oh, why didn’t you tell me when I first got here? Let’s go get wasted!” There are zero consequences attached to Ron finding out. Meanwhile, you’re building these elaborate ‘near-miss’ jokes where Ron almost finds out that this is a real wedding. But we don’t laugh because we know that Ron finding out doesn’t matter.

Let me give you a comparison wedding movie that got it right – Meet The Parents. In that movie, Greg loses Robert DeNiro’s beloved cat, Jinx. The movie spent 60 minutes building up how much DeNiro loved his cat. So when Greg loses Jinx and has to cover it up, we’re laughing our asses off because we know he’s in deep shit. Greg goes to a vet and gets a cat that sort of looks like Jinx to trick DeNiro. When he shows up with that cat, we’re both terrified and laughing at the same time because we know how screwed Greg is if DeNiro figures it out.

This was an unfortunate misfire because it had a lot of things going for it. In comedies, you need at least one hilarious character and they had that in Ron. But I think they made an error in moving the story away from the vacation. That was my favorite stuff.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: The comedy combination of a strait-laced character and a reckless character is as old as comedy itself. Your job is to look for ways to freshen it up and the Mullens did a great job of this. They extended the strait-laced character to a straight-laced couple and extended the reckless character to a reckless couple. That’s the biggest thing this script did right, and it resulted in a lot of funny moments.

Genre: True Crime – Murder

Premise: Based on the New Yorker article by Nathan Heller. A true-crime thriller based on the story of two brilliant college lovers convicted of a brutal slaying. An obsessed detective investigates the true motives that led to a double homicide, and the decades of repercussions that follow.

About: This script finished with 10 votes on last year’s Black List. The writer, Aaron Katz, is also directing. The project has already cast its leads, with Sabrina The Teenage Witch actress Kiernan Shipka playing Lizzy. Former Disney boy and rising star, Cole Sprouse (Five Feet Apart), will play Jens. Katz directed the 2017 film, Gemini, starring Zoe Kravitz.

Writer: Aaron Katz

Details: 122 pages

I’ve never understood giving real life murder stories the movie treatment. They’re always so much better in documentary form. I think if you’re going to do true life murder stuff, you should use the stories as inspiration then make up what you want to make up. That’s how Thomas Harris created Buffalo Bill and Hannibal Lecter. He found real life murderers who did weird shit and molded them so they fit into his fictional narrative.

Unless you can find a truly crazy murder story. But even then you might still want to use the characters as inspiration. Isn’t that what Tarantino did with the Helter Skelter crew in Once Upon A Time In Hollywood?

Anyway, on to today’s true crime murder story, which I’d never heard of before.

It’s 1985.

College kids Lizzy Haysom and Jens Soering meet at a movie theater. Afterwards, Lizzy tells Jens that she loves to make men fall in love with her and then fuck them over. But that she’s not going to do that to Jens because he’s “different.” “You’re not included. You don’t feel like a man,” she says. “I mean that in a good way. You feel like you. You’re not a man or a woman or anything.”

Um, okay.

Lizzy introduces Jens to her parents and, a week later, after they’ve gone back to school, we learn that her parents were brutally murdered, stabbed dozens of times each. 30-something cop Reese Rezek is assigned to the case. Right away, she suspects that there’s something fishy going on with Lizzy so she brings the couple in, one at a time, to chat. When certain parts of their stories don’t match up, she knows she has the killers.

Except before she can throw them in the slammer, they run. And they run far. All the way to France. And then Italy. Back in 1985, when someone ran, you couldn’t really do much about it. To make things worse, Reese is re-assigned to work in the DEA. So she spends a year busting people for drugs. But she never stops thinking about Lizzy and Jens!

Lucky for her, she finds her way back into homicide and convinces her outfit to let her track down the murderous couple in Europe. Off she goes with her partner and actually FINDS THEM dancing at an Italian club. They see they’ve been spotted and run, resulting in a race across town, and the couple literally jump into a train car to escape. So close and yet so far, Reese must cut her losses and go BACK to the US.

Eventually, however, they get picked up for cashing bad checks and Lizzy confesses that, yes, she killed her parents. Jens decides to take his chances in court but loses and both of them get 100 year sentences. But this doesn’t satisfy Reese, who starts having doubts! She becomes convinced that this other guy, Doyle, is the one who committed the murders. Our final act is about nailing Doyle to that metaphorical cross but Doyle proves, without a reasonable doubt, that he wasn’t there that day. I guess Reese was right the first time. The End.

Whenever I read a true murder story and I’m assessing if it’s “movie worthy” or not, the first question I ask is, “What’s fresh here?” Which is a question any good reader/producer/executive/director is going to ask when they read any script. What’s fresh here? Which means that’s a question YOU need to ask about your own concepts BEFORE YOU WRITE THEM. Because BELIEVE YOU ME, someone’s going to ask that question down the line and you better have an answer for them.

And it’s a question I was asking all the way through, “Blood Ties.”

You’re already starting from a place of weakness with the murder victims in Blood Ties. There’s a reason you don’t see, “Elderly Man/Woman Stabbed To Death” on the front page of CNN ever. Murder stories don’t gain national attention unless it’s a young woman or a child. Say what you will about how f*cked up the human mind is for thinking that way but it’s a reality. And it’s something you definitely want to consider when you’re assessing whether a true murder story is worth turning into a movie.

The reason it’s a big deal is because you need as much anger and demand for justice from your reader as possible in these stories. The less anger they have about the murders and the less demand for justice they have, the less they’re going to care whether your protagonists catch the killers or not. And that’s the whole name of the game. You want us to want the heroes to catch the killers.

There are caveats to this. If you spend a good amount of time with the elderly people who eventually get murdered and really make us like them, you can create enough motivation for us to want to see their murder avenged. But Blood Ties doesn’t do this. In our one scene with the parents, we barely learn anything about them. And I feel bad for saying this but, the truth is, I didn’t feel anything when they were murdered.

So you have elderly victims who I didn’t feel anything for. Not a great way to start off a murder script.

I guess if I’m arguing the writer’s point of view, I’m banking on the reader being interested in this weird couple, specifically Lizzy. I’m hoping that you’ll find her so odd that it’ll pique your curiosity enough that you’ll want to keep reading.

But if that’s what you’re hoping is going to drive the reader’s interest, ‘sorta weird’ isn’t going to cut it. The characters have to be flat-out bizarre. They have to say really weird shit and do even weirder shit. That’s why the Mansons captivated the world. Meanwhile, Lizzy and Jens topped out at “mildly odd.” I kept waiting for them to be “movie worthy” but they repeatedly failed to deliver.

The script also has a little bit of Fincher’s “Zodiac” thrown in. The story follows Reese as she becomes obsessed with finding Lizzy and Jens. That leads to us learning a lot about her character – such as the fact that both her parents died when she was young – that her dad was supposedly a great cop. But just knowing more about the protagonist’s life doesn’t mean that the reader will care about them.

That’s a common misconception. You can tell me a million things about your hero and I still not give a shit what they do. It’s how you package their backstory with their fatal flaw and their relationships and their personality – it’s the way you mix all those ingredients into a meal that determines if we like the character or not. I felt like I knew a lot about Reese. But there was very little done to make me root for her.

Elderly victims + didn’t feel anything for the victims + mildly odd murderers + a protagonist who I don’t care enough about. It’s nearly impossible to salvage this equation.

The one time I saw it done was Spotlight. TERRIBLE SCRIPT that had similar problems to Blood Ties. But the story in Spotlight was so good and so powerful that it somehow was able to override all of its weaknesses. Unfortunately, Blood Ties doesn’t have that “Helter Skelter” story centerpiece to make up for its averageness in all the other categories. And, for that reason, it didn’t work for me.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: When your movie has already resolved its primary conflict and you try to tack on a follow-up mystery to your story, you’re fighting a losing battle man. The audience has already checked out. It’s really hard to blow up the balloon for the entire movie, burst it, and then try to blow up a second balloon for the last 30 minutes. I think that’s successfully been done like 3 times in cinema history. That’d be like Indiana Jones surviving the Ark of the Covenant at the end of Act 2 and then he decides to go look for the Needle of Enlightenment in Act 3.

Guess what day it is?

It’s SCRIPTSHADOW WRITE A COMEDY SCRIPT IN 3 MONTHS BEGINNING OF WEEK LIST OF THINGS FOR YOU TO DO THIS WEEK day.

For those unfamiliar, Comedy Showdown is going down June 17th. That’s the submission deadline. In the meantime, I’m helping you write your script. I’ve already done Week One here and Week Two here. But even if you didn’t know about this until now, there’s still plenty of time to write a script. You’ll just need to up your pages-per-day. At the moment, I’m asking for 3 and a half pages a day. You might have to up that to 5 pages. Or, if you’re okay with not doing a final polish on your script, you can stay at 3 and a half pages.

Now, a little structure talk here so you understand what we’re going to be doing over the course of this week. For starters, we’re structuring our comedy assuming it’ll be 100 pages long. For our first draft, we are writing 1/4 of our script a week. Last week we wrote the first quarter (pages 1-25). Now we’re going to write the second quarter (pages 26-50).

This will take us to the script’s halfway point.

To make things easier for you, we’re going to be using the Sequence Approach and dividing this quarter into TWO SEQUENCES, each of them 12 and a half pages long. The first of those (pages 26 – 37.5) is commonly known as the “Fun and Games” sequence and is, arguably, the whole reason your came up with your idea. This is the section where you aggressively deliver on the promise of your premise.

Think about that first moment when the guys woke up in The Hangover. There’s a baby. There’s a tiger. Someone’s missing teeth. Those next 12 and a half pages delivered on the promise of the premise of waking up after a crazy night out and having no idea what happened the night before.

Or take Coming To America (the original). This is the moment where Prince Akeem and Semmi show up in Queens for the first time. You got the crazy New York cab driver who speaks his mind. The guys finding out that “Queens” is nothing like it sounds. Trying to get an apartment in New York for the first time. You are literally leaning into all of the funniest gags you can come up with from two guys who have never been to America… coming to America.

In other words, this should be the most fun you have the entire script. If you’re not laughing as you come up with fun new scenes for this section, you probably picked a lousy idea.

Where things get tough is in this second of the two sequences you’ll be writing this week (pages 37.5 to 50). This section isn’t as clear. In fact, I don’t know if anyone in screenwriting history has given it a name yet (feel free to suggest a name in the comments). But the good news is you know the exact number of pages it has to be – 12 and a half – which isn’t that many. And you know exactly where this sequence ends – it ends at your screenplay’s midpoint. Which means you can write towards your big midpoint moment.

The midpoint of a script tends to be the time where something big happens. That thing could be negative or positive. As long as it’s A BIG DEAL. It should also, preferably, alter the script in some way whereby the second half of the movie doesn’t feel exactly like the first half. This is a common newbie mistake. New screenwriters make the same jokes for 100 pages. You need something that alters the plot so that the jokes (and story) feel different.

I recently rewatched “Spy,” and the midpoint of that script is a positive one. It’s the moment where our spy, Susan Cooper (Melissa McCarthy), finally befriends target Rayna Bayanov, while having to maintain her cover. The entire first half of the movie was built around Susan trying to get to Rayna. In the second half of the movie, she befriends her, but must keep her cover. That change creates a whole new set of plotlines and jokes.

In Guardians of the Galaxy, which is essentially a comedy, the midpoint is a negative one. Peter Quill and his team lose the orb to big baddie, Ronan. This, of course, sets the stage for the second half of the script, which will require our misfit team to retrieve the orb before the bad guys activate it, destroying the universe.

During both of these sections, I want you to be focusing on two things. One, keep throwing obstacles at your hero. Especially in the second sequence. The first sequence – our “Fun and Games” section – is more about having fun with the concept. But having fun is often about throwing things at your hero that they have to deal with. So you’re going to pepper some of that in there as well.

Once out of the Fun and Games section, you’re in slightly more ‘serious’ territory. So you’re going to ramp up the obstacles. For example, in “Spy,” you’re going to throw an assassin at Melissa McCarthy. You’re going to blow her cover when she’s in the middle of a difficult task. Think of yourself as the “Obstacle God.” Your job is to create obstacles that you then drop into your film.

Comedy is often about being as shitty as possible to your hero and watching them squirm. That’s where the fun is! If you aren’t challenging your hero consistently, there isn’t going to be a lot of opportunity for laughs. If you find yourself writing dialogue scenes where you’re desperately looking for the next joke between two characters, chances are you’re not throwing anything at them. You’re leaving them to blow aimlessly in the wind – and that’s where comedy dies. When you throw obstacles at your hero, you don’t have to look for laughs. The laughs organically come to your heroes as they swat away all the shit you’re throwing at them.

The second thing I want you to focus on is reminding the reader what your hero’s flaw is. You do this by continuing to give them opportunities to overcome their flaw only for them to not be up to the task yet. Obviously, if they were up to the task, your movie would be over.

Look at Steve Carrel’s character in The 40 Year Old Virgin. His flaw was arrested development. He’s still stuck in his childhood, which explains why he hasn’t had sex yet. As a writer, you want to challenge that flaw to remind the audience what it is your hero has to overcome. In this case, Steve Carrel’s girlfriend suggests he sell his valuable childhood action figures to start his dream business. Carrel resists this, at first, to let the audience know he’s not ready. He hasn’t overcome his flaw yet.

If you don’t occasionally remind the audience of this over the course of your screenplay, then, at the end, when you try and write your big heartstrings-tugging moment, there ain’t gonna be any tears. And you’re going to ask people, “Why aren’t you crying?” And they’re going to say, “Because that whole ‘he’s finally ready to grow up’ moment came out of nowhere!” “Came out of nowhere” is code for you didn’t set it up properly. Which is why you need to keep reminding your reader that your hero hasn’t overcome his flaw yet.

One last thing. Don’t worry if your page count is a little long. If it feels like you’re going to hit 120 pages instead of 100, that’s okay. I’ve found that, in comedies, there are always going to be a few characters you don’t “get” the first time around. You’re trying to find where their ‘funny’ is in that first draft. And the best way to do that is to let some scenes run long so that your ‘trouble’ character gets a chance to find his voice. That might even mean changing him in the middle of the script because he wasn’t working in the first half. In the end, the biggest thing you’re going to be graded on is, “Is this funny?” So if characters aren’t working, you need to play with them and give them opportunities to let go. Sometimes it’s a single line you write that helps you finally ‘get’ a character.

Wow, at the end of this week we’re going to be halfway through our script! Who said writing a screenplay was hard?

Onwards and upwards!

Writing great comedy scripts does not come down to plot or theme or even, as commonly assumed, dialogue. It comes down to how funny the key characters are in the script. Are they constructed in such a way that they are inherently funny without having to do anything?

When you manage to construct an inherently funny character, it is magic fairy dust for your screenplay. You don’t have to think of funny things for them to say or do. They just say and do them. Contrast this with weak comedy characters who you always seem to be moving mountains for to get just one funny line out of them. Get the character right AND HE BECOMES THE COMEDY.

What we’re doing today is listing ten great comedic roles and you’ll see pretty quickly that there’s overlap. In other words, pay attention to the kinds of characters who become iconic because their DNA on ‘how to write funny’ is right there for the taking if you want it.

Here we go!

Alan in The Hangover – Alan’s primary characteristic is that he’s the most socially unaware person in the world. Combine this with a character who likes to talk a lot and you get someone who’s always going to be saying funny things. This is a comedy staple. You saw it with Dwight in The Office. You saw it with Kramer in Seinfeld. There are variations here on how goofy you want to get with these characters. But socially unaware characters who like to blast their opinions on everything consistently become some of the funniest characters out there.

Walter from The Big Lebowski – Aggressive. Mentally unstable. Paranoid. Note the extremes of the adjectives we use to describe Walter. He’s not “kind,” or “sweet,” or “pleasant.” He’s AGGRESSIVE. He’s PARANOID! Big exaggerated negative traits are great for comedy. We also have a character, like Alan, who loves to talk! Characters who express what’s on their mind have more ‘funny potential’ than characters who keep to themselves.

Derek from Zoolander – Derek is really really really really really really really dumb. Again, note the EXTREME here. Extreme works well in comedy. If Derek is only sort of dumb, there aren’t as many laughs. Also, Derek plays into a stereotype – that all models are dumb. While everyone is freaked out about stereotyping these days, it’s one of the best ways to construct a funny character. For example, if they made Zoolander today, it would not be controversial. Find that stereotype and play it up!

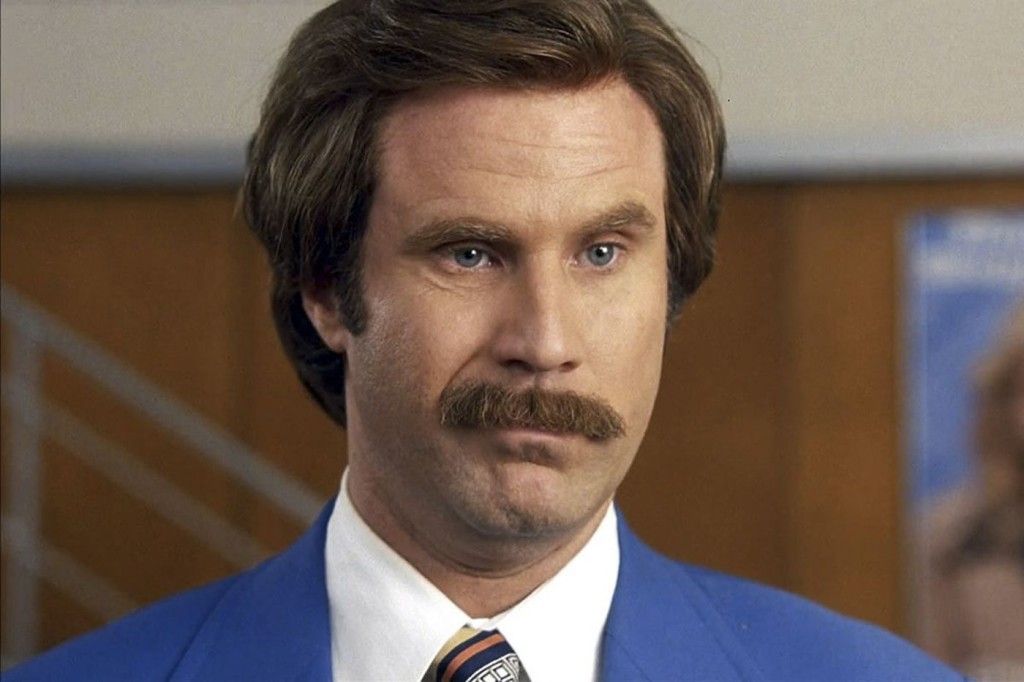

Ron Burgandy in Anchorman – His name is Ron Burgandy? Ron Burgandy exhibits another staple for hilarious characters. He’s clueless. The guy has no idea what’s going on around him is usually funny. But where you get those big laughs from Ron Burgandy is that he thinks he’s amazing. That’s always a great combination to play with in comedy. You take a negative and you contrast it with a positive. This guy’s so clueless. And yet, if you asked him, he’d tell you he’s the second coming of Christ. That gap between who he is and who he thinks he is is where all the laughs are.

Megan from Bridesmaids – Melissa McCarthy stole Bridesmaids with this character and she has the writers to thank for it. Megan is your classic “no filter” character. Comedy LOOOOOOOVVVES no filter. An additional note with this character. The temptation is to look for her laughs from dialogue. Don’t limit yourself. Extend the ‘no filter’ mindset to that character’s actions as well. One of the funniest moments in Bridesmaids is when Megan steals nine puppies from the wedding party.

Stifler from American Pie – We’ve got our first villain! American Pie did something really genius with Stifler which is why he became the most memorable character of the franchise. He got it as much as he dished it out. He makes fun of everyone but gets peed on at the party. He cusses nerds out but ends up drinking a beer full of semen. He beats people up yet a nerd has sex with his mom. This supports my theory about contrast being the key to comedy. If Stifler is just a dick the entire time and never gets payback for it (until the last scene), we don’t experience any contrast in his character. It’s going from one extreme (a Stifler win) to the other (a Stifler loss) that keeps his character hilarious.

Happy Gilmore – Happy Gilmore plays with one of the simplest comedy types available: the angry dude. People who get insanely angry are funny. If Happy Gilmore is only kind of angry, his character doesn’t work. Instead, this is a guy who tries to beat up national treasure Bob Barker from The Price is Right (The Price is Wronnnng, bitch!). Comedy’s often about going one yard further than the audience expects you to go. Happy Gilmore has 30+ examples of that. And it’s a great approach to writing comedy in general. Think about where the reader expects you to go with the joke, and then take one yard further.

Vizzini from The Princess Bride – We’re adding a second villain to the list. Inconceivable! Vizzini is built around his outsized ego. This is another area where we find contrast. Vizzini is this tiny little man. Yet he has the biggest ego of anyone in the movie. It’s that contrast (or irony) that makes the character so fun. And, again, you see that comedy works well with extremes. Vizzini believes he’s the most intelligent person in the world. He believes everybody’s not just dumber than him, but WAY DUMBER than him. That’s where you want to be thinking with comedy. You want to go to those extremes.

Borat – Misguided confidence is one of the funniest traits you can play with. Why is Borat so confident? Why does he walk into every situation with such assuredness? That contrast between his extreme confidence and engaging with a country he knows nothing about is where all the fun is. Borat is not funny if he’s constantly doubting himself. He’s not funny if he’s depressed and uninterested in his surroundings. He’s funny because of his outsized confidence in a number of scenarios where there is no reason for him to be confident at all.

Stapler Guy in Office Space – I thought I’d put Stapler Guy in here because he’s so unlike any other character on this list. Most of these characters are loud and in your face. Stapler Guy is quiet and mumbles all the time. So why is he still funny? Mike Judge flipped the script on this. Most funny characters are built around what they put out into the world. Stifler and Ron Burgandy and Happy Gilmore – these are all people who throw their personalities into the world. Stapler Guy is the opposite. His entire persona is built around how the world treats him. Nobody respects him. That’s the joke. People keep kicking him and kicking him and kicking him. And I think that’s why he’s so funny, is that a lot of writers would start to feel bad about kicking someone so much. Mike Judge doesn’t. He just keeps kicking. And he adds this brilliant little twist whereby Stapler Guy tries to fight back but nobody can hear him because he’s a mumbler. Sometimes being RELENTLESSLY HORRIBLE to your character can make him hilarious.