Search Results for: amateur

So today I wanted to do a little interview with Jim Mercurio, one of the many friendships I’ve been able to formulate through the Scriptshadow blog, and let you know about his contest, The Champion Screenwriting Competition, currently running, which has a $10,000 Grand Prize. I first became aware of Jim through a contest I held over at the Done Deal site. He wrote this unique script about a seriously dysfunctional relationship that was sort of like a Woody Allen film if it were on speed. It was called, not surprisingly, Dysfunction Junction. Wanting to know more about the warped mind behind this story, I got in touch with him, where I found out he’s been at this game for a while, having worked as a development executive for Allison Anders, directing the first six years of the Screenwriting Expo’s screenwriting contest, and written a column for Creative Screenwriting magazine. In between making a low budget film every other year, he now manages to put out his own free monthly ezine Craft & Career. I used the excuse of promoting his contest to get myself some free screenwriting advice!

SS: First of all, why don’t you tell us a little about yourself and your contest? What inspired you to start it?

JM: The name of my contest, Champion, says a lot about what I’m trying to help these writers achieve. I want to encourage writers and help them grow, and when they’re ready, give them access to the industry. Almost ten years ago, Erik Bauer, then-owner of Creative Screenwriting and founder of the Screenwriting Expo, asked me to design and run the Expo competition because he thought I had the risk-taking gene. All of us writers are risk-takers. Choosing this career and writing on spec is a huge gamble. I hope the excitement of vying for $10,000 motivates these writers to do their best work, and it feels great to be able to reward them. I also invite the top writers to a weeklong party called the Champion Lab. We’ve got to feel rewarded as writers, on some level, or it’s tough to stay motivated.

SS: In general, are contests worth the risk?

JM: If your writing is competition quality, then contests can be a smart and reasonable investment. There are other benefits aside from the Grand Prize — the excitement of waiting for results; making friends and connections on message boards like Done Deal and Movie Bytes, and having a deadline, which helps you to crank out those pages. However, if you enter a dozen contests where your script is the sort that the contest purports to reward and you don’t advance in any of them, consider spending the next $600-$1000 educating yourself and honing your work with classes, coverage, consultants, etc.

SS: You’ve read a ton of scripts, I’m pretty sure way more than I have. What is the big difference you see between amateur scripts and pro scripts? What really sticks out in your mind?

JM: If you don’t want this to turn into a 20-part interview, give me some leeway to give a smart-ass answer or at least a creative one.

SS: Go for it.

JM: I am going to make up a word. Most aspiring writers’ scripts don’t have a high enough “story density.” Story density is the amount of good storytelling you can cram into 110 pages. For beginning writers, there is often too much dead space between the good shit in their script. For some, it might be cumbersome language or style. For others, it might mean the antagonist’s plan in their action script doesn’t have enough twists. In a non goal-oriented script, it might mean a sequence goes slightly astray and wastes our time. Check out the first page of The Beaver. The Beaver’s first page has high story density. I know, that sounds bad.

SS: Okay, let’s get more into craft later. What do you personally look for in a screenplay?

JM: I think some contests and university writing programs overvalue the “heaviness” of a subject. Let’s say we take To Kill a Mockingbird and The Nutty Professor. When the writer aims for the To Kill a Mockingbird masterpiece but only accomplishes 55% of his goal, you can’t argue that it is a better screenplay than a well-crafted broad or high-concept comedy that accomplishes 95% of what it set out to achieve. Screenplays can’t be compared or quantified like that. Their aim is not to be literature. The best screenplays are blueprints for stories meant to be told on film that will meet their audience’s expectations. The closer writers get to accomplishing their goal with a script, the more of a chance they’ll have to satisfy their audience.

I look at scripts for what they are trying to be. I want them to aim to surpass what the other writers in the genre have already consistently achieved. And then I look at how well the craft and execution achieves that goal.

SS: If you were a new writer, sitting down to start your next script, how would you approach it to give yourself the best chance of selling the screenplay?

JM: It depends on how new the writer is.

SS: What do you mean?

JM: If you are a beginning writer, write WHATEVER script you want to write and then finish it. Use it to develop your craft, learn your strengths and weaknesses, and grow as a writer.

SS: Yeah but come on. You remember what it was like writing those first few screenplays. The last thing you wanted to hear was that your script was basically worthless, that all it was good for was “to get better.”

JM: True, but that’s what screenwriters have to learn. This industry isn’t a cakewalk. It takes several scripts, sometimes up to a dozen, for most writers to reach a tipping point with their craft. And that’s okay. Don’t think of it as “it doesn’t matter,” think of it as practicing free throws at 11pm when everyone else has gone home for the night. This is your preparation for the big leagues. So write whatever material you’re passionate enough to FINISH, and when the moment comes, pick a genre you know or love so you can transcend it. You have to be willing to do the research or brainstorming to make sure you can nail a genre. For instance, if you aren’t up to the challenge of finding a hundred clever and integrated ways to exploit, say, the first-person camera technique, then don’t write Rec or its American remake Quarantine, Paranormal Activity, The Blair Witch Project or Cloverfield.

SS: Okay, so this leads to one of my favorite questions: “Should I write a more character driven piece, something I can put my heart into? Or should I write something more high concept, despite my heart not being in it?” The argument is that the character-driven piece will have more depth, but Hollywood is scared off by the fact that it’s not marketable. The high-concept script is more marketable, but is often labeled as “not having enough heart.” Which route should I take?

JM: I think the answer is both.

You are going to write several scripts on your way to learning the craft, so I suggest writing each kind of script at some point.

SS: Well cause I know Dysfunction Junction is a passion project of yours, and that comes through in the writing. But it’s still a hard sell, right?

JM: Unfortunately, it’s true. The problem is, even if something’s good, that might not even be enough. When I entered the industry in the 90s, I fell in love with movies like Allison Anders’ Gas Food Lodging. Maybe they gave me hope…or false hope… that personal cinema could be done in and around Hollywood.

If you have a character-piece, decide one of two things.

1) It’s a sample: Spend six months on it. Get it done. Move on to the next script.

2) You are going to make it: You can’t really control if it gets made, but you can make it actor bait, easy to shoot, and maybe even have rabble-rousing material (In the Company of Men, The Woodsman). Be or find a “producer.”

At some point, you should write a high-concept script, but be warned — writing a well-integrated, high concept piece is labor intensive. Look at the first draft of your high concept story and circle the conflicts that are unique to the script’s specific set up. And then circle the ones that are generic (like the drugged out sequence in Land of the Lost, wtf?). If you are not at an 8:1 or 9: 1 ratio between the cool/specific-to-the-concept stuff and the could-be-in-any-movie stuff, then you are not going to compete with Leslie Dixon and Freaky Friday or Charlie Kaufmann and Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind. You have to hit most of the character beats of the character piece but you have to cleverly wrap it ALL around the concept.

One of the goals of in my workshops is to illustrate the subtlety of craft and how understanding the exploitation of concept and the inner workings f character and theme are both essential to writing scripts that have a chance in the marketplace. I actually wrote an article about it here.

Why can’t movies be both character pieces and high concept? If writers do have a tendency or skill toward one or the other, then the real skill is to make sure that they can complement the high concept or genre script with character, or the character piece with some hook.

Are Chinatown, Citizen Kane, and The Godfather smart character pieces or high concept fare? I went old school on purpose. But what about Memento, Wall Street, or The Sixth Sense? If Eternal Sunshine doesn’t have great characters and really honest things to say about memory, shared experiences, and love, it comes off as a confusing gimmick.

SS: As long as I have you here, I’m going to be selfish and get your thoughts on a couple of things I’m always trying to improve on. What are the keys to writing good dialogue and strong characters?

JM: Your readers can check out your Facebook from earlier this week for a link to a longer piece I did on dialogue in Craft & Career. But basically, with dialogue, your creative freedom comes from the clarity of the beats, not the words themselves. Go and watch the famous “I could’a been a contender” scene from On the Waterfront. There is all this heavy stuff about the depth of his brother’s denial and betrayal, about life-changing epiphanies and how relationships will be forever changed and possible lives lost. Brando is overwhelmed with the surprise and revelations. And his response is simply… maybe the first modern hip usage of the word: “Wow.” It only takes those three letters to capture his shock, disbelief and sense of loss.

As far as character goes, I don’t think that there is much debate about the theory. A story challenges the character’s deep-seated beliefs and hidden wounds until the character comes to a crisis and a chance to change. I think what it comes down to is craft. Can the writer find the action and situation that can make these inner machinations external? Can they succinctly show us the character’s essence?

Let’s say you want to show that your character is smart. You have a scene where he uses three or four explicitly spelled out and logical steps to make a deduction. That’s not going to work for a Jack Ryan or Gregory House character. Cut out most of the baby steps and let your character make one big leap of logic, intuition or faith. In every Harrison Ford thriller, there will be a scene where a subtle visual cue will be all the character needs to jump into action. In Air Force One, he sees milk dripping from a bullet-riddled cart — CUT TO: he dumps gas from the fuel tank. Okay, he’s smart. But the challenge is at the scene level — can the writer reveal it succinctly with elegance or cleverness?

SS: What is the biggest mistake you see writers make?

JM: Hmm, having read half a million pages of screenplays, I am not sure I can pick just one. Here are a few.

Not writing. If you’re a beginning screenwriter, write a few scripts. They may suck. So what? Keep writing.

Beware of the faux masterpiece. What is that? That’s when you try to tackle something huge like a critical piece of history – the Holocaust, slavery, World War II – or try to set an expensive politically-charged love story against that sort of backdrop. You might be a deep thinker and have an unparalleled understanding of the subject, but as a beginning writer, your craft is not going to be able to do the story justice.

You don’t write The Unbearable Lightness of Being, Schindler’s List, Sophie’s Choice or even Atonement as your third or fourth script. When a writer aims for that sort of script – one that only works if it’s a masterpiece – then whether they achieve 50% or 75% of their goal, it’s sort of irrelevant. They haven’t crossed the tipping point where the script has any viability.

SS: Great point about the faux masterpiece. I see a lot of those. But does that mean writers shouldn’t try? Aren’t you the guy who is supposed to be championing people? Ore you are contradicting yourself…you said writers should write whatever they want when starting out.

JM: Fair enough. If you are writing your attempted masterpiece to learn about screenwriting, go for it. And get it over with ASAP. The skill you need to pull off the masterpieces come from finishing several non-masterpieces.

So, let me contradict myself again. One of the biggest mistakes is to not have high enough expectations. Writers shouldn’t just nail a genre. They should innovate and transcend it, too. For example, The Hangover is an okay mystery but the genre-crossing makes it a great comedy. When you come up with a hook like Memento or Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, you will spend several hours banging your head against the wall to find your way through it. If your script isn’t driving you nuts, then you didn’t challenge yourself enough.

And when you are finally in control of your craft… PREACHING TO THE CHOIR ALERT, CARSON! … If you want to be calculating and commercial-minded, aim for modestly budgeted high concept fare with a good hook.

SS: Choir preached to indeed. I know each contest is different, but is there a specific type of script that does better in a contest?

JM: It’s the writer’s responsibility to research who’s running and judging a contest. Look at the winners from previous years. If the contest is giving away 10K or 20k to period biopics, stuffy dramas and literary-sounding faux masterpieces, then don’t enter your “Die Hard in a skyscraper” script, right? Be aware of their tastes and limitations.

Because the stakes in the production world to find good in a screenplay or to find a good screenplay at all are higher than in the contest world, I suggest making your contest script a little bit more the “theoretical good script” that the screenwriting education niche prescribes. You know — being a good read, having no typos, having a brisk pace, setting up the reader’s expectations very quickly regarding tone and genre and being less than 120 pages.

SS: What types of scripts do better in your contest?

JM: I have an inner film snob that appreciates film as an art form. My last script’s influences are Bergman’s Scenes from a Marriage, the plays of Patrick Marber and Neil Labute and a few French films like Romance and Dreamlife of Angels. And I have made three low concept features as a director or producer. On the flip side, I am also first in line at the Thursday midnight screenings for The Lord of the Rings and Iron Man and have given development help to some of the most commercial-minded people in Hollywood.

I pride myself on being able to appreciate good screenwriting “across the board.” Last year, Champion feature winners were a high concept comedy, a coming-of-age drama, and quirky buddy picture. One of the shorts winners was a masterpiece (non-faux) and the other a smart comedy.

We have a prize (and a micro-writing deal or option) for best low budget horror and our short categories include prizes for serious scripts, comedies and best script under three pages.

SS: I think contests are a great way for new writers to test their mettle. If your script is good, it will do well, which gives you confidence, pushes you further along in the industry, and buffers your bank account in the process. But I always believe in a multi-faceted attack. So while these writers are waiting for their names to be announced as winners, what else should they be doing to break into this industry?

JM: Writers need to know what stage they’re at in their writing career and act accordingly. The basic stages:

1) Learning – They need to knock out a couple scripts, get some feedback, read scripts, watch movies, take in every opportunity to improve.

2) Mastering the Craft – Here, writers start choosing scripts with some practicality in mind and are writing a couple of scripts per year. They enter contests and share their work with peers or professionals who are willing to give feedback. Don’t blow a potential contact by submitting a script before it’s ready. When you have confirmation via peers, contests and professionals, then you are ready for the final stage.

3) Marketing – Spend some time studying queries and loglines. Consider pitch services and get your material to producers and managers, or people who can help you get your script read. Contests might be a part of your strategy but use your wins or advancements as ammunition in cold calls and query emails. Spend some time with the “salesperson” hat on and get your script out there.

SS: Can you tell me anything else about your contest? Entry fees? Deadline? Where you sign up? Any tips you have to improve the readers’ chances?

JM: With WithoutABox discounts our entry fees are still less than $45 and shorts are $20. I think our prices are the lowest of any of the contests with a Grand Prize of $10,000. For an additional $40, entrants can enter our Coverage Category (and get a free copy of my DVD Killer Endings) and receive a page and a half of notes. Coverage will never be the Holy Grail of insight into improving your script, but I designed the category to help writers advance to the next round where their script garners additional attention. It’s meant to take some of the luck out of the process.

May 15 is the Regular Deadline and the last chance to use the Coverage Service.

Enter at www.championscreenwriting.com.

Even if you aren’t entering the contest, please sign up for my free newsletter there.

If you have any questions about the contest or anything else, please feel free to drop me a line: info@championscreenwriting.com

SS: Last question. I understand you just got back from Paris for work, right? How the hell did you get out of the country? Did you take a tramp steamer back here?

JM: Yeah and I met a hobo on the tramper who was working on a script. We made a barter deal. In exchange for a semi-stale baguette, I told him his second act was way too long.

SS: And that’s it. Thank you Jim for taking the time to let Scriptshadow pick your brain.

JM: It’s all good. Thank you.

SS: I hope you find the next Aaron Sorkin in your contest. (And I hope he’s reading this sentence right now!)

If last week was weird, this week will be wacky. There ain’t no unifying theme here I’m afraid. Today Roger hits you with a horror thriller. Tomorrow, I’m going to review a script from a writer who has a hot mysterious project out there somewhere (to, of course, drum up awareness that I’m looking for said hot mysterious project’s script). Wednesday we’ll either have a writer interview or another book-review post. Thursday will be a quiet character driven story review. Then Friday will be something I’ve never done before. If you’re a fan of sci-fi, you’ll want to tune in, cause I’m writing 3 mini-reviews of hot sci-fi projects around town. — Now, if you haven’t heard about the craziness happening in the month of May here at Scriptshadow, time to go back and read that post. And when you’re done wrapping your head around all of that, come back and read Roger’s review of “Pet!”

Genre: Thriller, Horror

Premise: A lonely animal shelter worker descends into a downward spiral of obsession when he stalks and abducts his crush, imprisoning her in a cage. But according to her diary, this young woman may be more deadly than she seems.

About: Jeremy Slater’s “Pet” sold to MGM back in 2007, the same year that his spec “Score” landed on the Black List. Since then, he sold “My Spy” to CBS Films, which has been described as Three O’Clock High meets Alias. Last week, Slater made the headlines again when it was announced that he was the writer on a Dreamworks airport thriller project pitched by none other than Alex Kurtzman and Roberto Orci.

Writer: Jeremy Slater

Details: 1st Revision dated 5/19/07

Last week, we all heard about Alex Kurtzman and Roberto Orci pitching a thriller set in an airport to Dreamworks. Flog me if you will, but I think these guys are brilliant pop writers, so I wasn’t surprised to read about them selling a pitch. What intrigued me was the name of the writer attached. A dude named Jeremy Slater. Why was this guy getting the Orci-Kurtzman seal of approval?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[xx] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

Genre: Indie Drama

Premise: An illegal immigrant in Los Angeles tries to start his own gardening business, only to see it ripped away from him, threatening he and his son’s future.

About: So you just directed one of the Top 20 franchise pictures of all time. You’re offered the opportunity to direct the next two movies in the franchise and probably double your already large salary in the process. Do you do it? Not if you’re Chris Weitz, who many of you know as the director of Twilight: New Moon, About A Boy, or, if you go back a ways, American Pie. No, Weitz said, I would rather direct a tiny independent film about an illegal immigrant living in LA who speaks in subtitles and that, in all likelihood, will be seen by 1/1000 the amount of people who saw Twilight. Had you heard that story, you’d probably call the guy nuts, right? I mean who walks away from all that money and power? Except it makes a little more sense when you consider Weitz’s path. The producers of the Golden Compass didn’t consult their moral compass when they dumped all over Weitz’s vision and basically pried the movie from his furious hands. And while his experience on Twilight was supposedly better, indications from an under-enthused press tour imply that he didn’t exactly have a blast on that film either. So there’s something very comforting about going back to a world where nobody looks over your shoulder (particularly in this case, where even if they did, they wouldn’t understand what the hell the actors were saying). And I, for one, admire Weitz for turning down the dough. The question is, did he turn it down for the right project? And that’s where we segue to Eric Eason, the writer of “The Gardener.” Eric is a writer-director himself, and this is the first script he’s written that someone else will direct (his most well known work is 2006’s “Journey To The End Of The Night,” starring Brendan Fraser and Mos Def. The plotline sounds surprisingly similar: “The tale of a son and his father separately plotting to escape the desolation of their lives in the lurid underworld of Brazil’s sex industry.” – I, like you, am hoping Brendan Fraser does not play Mos Def’s father) Anyway, it’s always exciting to see a passion project come to the big screen. So let’s see what it’s about.

Writer: Eric Eason

Details: 121 pages – Sep 20, 2009 draft (This is an early draft of the script. The situations, characters, and plot may change significantly by the time of the film’s release. This is not a definitive statement about the project, but rather an analysis of this unique draft as it pertains to the craft of screenwriting).

Those who have read this script have described it as “heartbreaking,” “honest,” and “beautiful.” Sounds like an Oscar advertising campaign to me. But it’s rare I hear those kinds of adjectives thrown around with scripts these days. So I wanted to be prepared. Now I don’t personally own any Kleenex because, you know, I’m a man and I don’t cry. But let’s just say if I did – and I don’t – but if I did, I would’ve placed them directly to the right of me just in case, all things considered, anything happened. Of course nothing would and I don’t own any Kleenex so this is all hypothetical but I’m just saying.

“The Gardener” is about a 40 year old immigrant worker from Mexico named Carlos Riquelme, who illegally lives in Los Angeles, California. Carlos used to dream of a bigger life. But after having a child and watching his wife leave him for another man, Carlos’s grand plans descended, like so many do, into just trying to make it through the day. The problem is, Carlos is at a crossroads. The man he works for, another immigrant, is retiring, and when that happens, Carlos won’t have an employer anymore. This means he’ll have to go all the way back to the bottom, working the corners of the lumber yards and the Home Depots, hoping to get picked for work every day. Not exactly stable income.

Carlos has an option though. His boss is offering to sell him his pick-up truck along with all his gardening tools for 14 thousand dollars. With it, Carlos can start his own business, and maybe, just maybe, finally get a shot at those dreams he had when he was younger. The problem is, Carlos isn’t legal. He can’t officially own the truck. He can’t officially get a license. So if he were to get pulled over for any reason, it’d be a trip on the Tijuana Express. Now even if Carlos *were* to explore that option, he doesn’t have the money. He can’t afford the truck. And, in all honesty, he can’t afford to risk getting deported and leaving his son here in America by himself. But his boss brings up a good point. On his current path, in his current East L.A. neighborhood, it’s only a matter of time before his 14 year old son starts gangbanging. They both see it. They both know it. So if Carlos doesn’t find a way to pull himself out of this poverty, out of this neighborhood, and into a new life, his son is fucked anyway. As far as he’s concerned, his boss says, Carlos can’t afford *not* to buy the truck.

So with the help of his sister, Carlos scrapes together the money and buys the truck. And in that moment, Carlos has never felt more hope. He’s actually doing it. He’s actually living the American dream. He immediately heads down to “Workers’ Corner” and grabs an honest-looking Salvadorian man, heading off for his first job in Beverly Hills as his own boss. And as he climbs up that first tree, preparing to clip it, he can only watch in horror as the Salvadorian man snatches his keys and phone, runs off, and STEALS HIS TRUCK. Carlos slides down the tree and barrels after him, but it doesn’t matter. He’s long gone. Carlos has just lost everything. Faced with this terror, Carlos grabs his son and the two go on a hunt through Los Angeles to find the Salvadorian and get the truck back.

Now I’m no expert, cause the only gardening I do is in Farmville. But from what I read, The Gardener plants a lot of the right seeds. Where this script truly shines though is in the way it raises the stakes. As I’ve mentioned before, amateur writers tend not to care about the stakes of their story. As a result, there are no real consequences to their characters’ actions. But if you know how to build stakes, you can make a tiny indie story just as riveting as the latest Steven Spielberg blockbuster. And that’s what we have here. First we find out Carlos is about to lose his job. Then we find out his kid will join a gang if he doesn’t get him out of the neighborhood. Then we find out he has to borrow the money to buy the truck, money he’ll then owe. Then we find out that even if he gets the truck, one traffic stop could send him back to Mexico. And on top of all of that, Eason stresses just how important it is for Carlos to provide for his son. For all these reasons, when that truck is stolen, you physically lift your hand to your mouth and say, “No.” It’s that powerful. It’s that horrifying.

In addition, Eason knows what to do once the truck *does* get stolen. That may seem obvious (FIND THE TRUCK!), but if all you show us is a bunch of attempts at getting the truck back, your story is going to get old fast. Eason has gently hinted at a rift between father and son in the earlier parts of the screenplay, so that when they’re finally forced together on this journey, the focus slyly shifts over to their broken relationship. And what I loved was how Eason approached that dynamic. It is so easy to turn a father/son relationship into a melodramatic mess of cornmeal mush. What Eason does to prevent this is he flips the old “son trying to earn his father’s respect” angle around to a father trying to earn his son’s respect. There’s something very, yes, heartbreaking about this approach. Carlos knows that his son sees him as some faceless illegal immigrant who whores himself out on a corner for work. That he is incapable of providing a real life for them. That he’s, for all intents and purposes, a screw-up. Watching Carlos try and reverse this perception is both sad and endearing. It really works well.

My only reservation about the script is ironically the thing I gave it the most credit for. Whereas the stakes were high in almost every respect, they weren’t high in the most important respect of all. The overarching threat throughout the story – if Carlos is caught by the police, he’ll be sent back to Mexico – isn’t really a threat at all. Several times throughout the script we’re reminded that if Carlos were to be deported, getting back to the United States would be a piece of cake. That unfortunately undermines every obstacle Carlos tries to overcome. Cause in the back of our minds we’re saying, “So he gets thrown out of the country for a week? Big deal.” This bothered me enough that it’s the key reason I didn’t give the script an impressive rating, which, throughout the first half, I was sure it would get.

However, this is an early draft, and there’s always the chance that this problem was addressed. Either way, this was a really entertaining script and there are enough powerful moments to make it a strong recommendation. If you like Sundance films or movies a little off the beaten path, check this script out for sure.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[xx] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: This isn’t the prettiest script in the world. It has its share of bumps and bruises and screenwriting class, “You can’t do thats!”. For example, emotions are explained right there in the action lines (i.e., “When he was younger, upon arriving here in this country, he brought with him many dreams…”), paragraphs bloat up to ten lines long, and there are formatting issues scattered throughout. But here’s why I overlooked them: The emotional core of this script is awesome. No matter how clumsy your screenplay is, if you get the emotion down, the reader will forgive you. Focus on your characters. Focus on their journey. Focus on them overcoming their weaknesses and becoming stronger people by the end of the story. If you do that, the reader will forgive a lot.

Hmm, this week is going to be a little crazy. I’ll be contrasting today’s huge fanboy review with something tomorrow that’s so independent, I’m not even sure I know about it. And I read it! The good news is, the script was great. As for the rest of the week’s reviews, it’s still up in the air, so anything goes. But to ease the pressure of Uncle Sam’s ridiculous monetary demands this Thursday, I’ll be making a big announcement that should get all of you amateur screenwriters in a frenzy. So stay tuned because that opportunity will be coming before the end of the week. Right now, buckle yourselves up for another Roger review…

Genre: Crime, Prophetic Horror, Action

Premise: A former Pinkerton detective is resurrected as a Sifter, a bounty hunter tasked with going after people who have skipped out on destined meetings in Hades. When he’s ordered to hunt down a young artist, his past literally comes back to haunt him. He’s forced to team up with his deceased wife, now one of heaven’s operatives, to stop an impending apocalyptic event known as The Awakening.

About: “I Died a Thousand Times” is Aaron Drane’s sophomore screenplay. Drane went to film school at UCLA, where this script won the UCLA Samuel Goldwyn Award. In 1997, the script yielded a million dollar payday when it sold to Arnold Kopelson. He sold a couple more scripts to 20th Century Fox and most recently wrote and produced the FEARnet web series, “Fear Clinic”, which stars iconic horror movie actors, Robert Englund and Kane Hodder.

Writer: Aaron Drane

Ironically, I never heard of this script until my friend let me wander around in his mystical script vault, which turned out to be kind of like the warehouse from Raiders of the Lost Ark, except the relics on these shelves were unproduced and forgotten screenplays. I got lost among the shelves of scripts, overwhelmed and paralyzed by the paradox of choice. Four hours later, I finally escaped the labyrinth with brass brads in my hair and paper cuts on my fingers, armed with a copy of Aaron Drane’s “I Died a Thousand Times” (not to be confused with the 1955 remake of High Sierra), a spec that purportedly sold for a million bucks back in 1997.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[xx] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

Genre: Comedy

Premise: (from IMDB) A series of bad investments forces a rich dysfunctional Midwest family to move to the sticks, seek out new friends and learn how to rely on each other.

About: “The Grigsby’s Go Broke” is one of a handful of unproduced scripts that John Hughes left behind, and the frontrunner to become John Hughes first posthumous film. For those who don’t know, Hughes dropped out of the University of Arizona in the late 1960s and began selling jokes to Joan Rivers and Rodney Dangerfield. He later became an advertising copywriter at Harper & Steers and then at Leo Burnett. He moved over to the National Lampoon magazine and penned a story called “Vacation ’58,” inspired by his family trips as a child. That story, of course, became the basis for “National Lampoon’s Vacation,” Hughes’ first big hit as a writer. After much success, in 1994, Hughes retired from the public eye and moved back to the Chicago area. He rarely gave interviews, save for promoting an independent film he wrote in 1999 called “Reach The Rock.” Although Hughes obviously made a lot of money in the business, it was a ridiculously sweet deal he got for Disney’s live-action “101 Dalmations,” which ensured that he’d “never have to work again.” He spent his later years farming, but did occasionally write under the pen name “Edmond Dantes.” While some say the pen name was because he wasn’t proud of the middle-of-the-road mainstream fair he was writing (Maid In Manhattan, Beethoven’s 5th, Drillbit Taylor), it’s unclear why he felt the need to write the movies in the first place, since, as pointed out, he didn’t need the money. It may be as simple as producer friends calling him and begging that he take a pass on their projects. Or maybe there’s another answer. I don’t know.

Writer: John Hughes

Details: March 2003, 2nd Draft – (This is an early draft of the script. The situations, characters, and plot may change greatly by the time of the film’s release. This is not a definitive statement about the project, but rather an analysis of this unique draft meant to further the education of screenwriters).

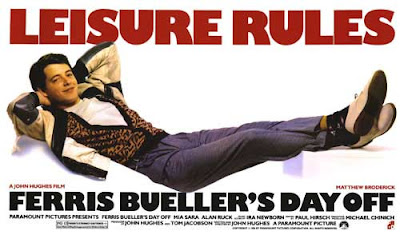

I feel like it’s my duty whenever I read a John Hughes script to point out just how amazing I think he is. “Ferris Bueller’s Day Off” is one of the top 5 comedies of all time. Hughes also wrote the great “National Lampoon’s Vacation,” “The Breakfast Club,” “Sixteen Candles,” “Planes, Trains And Automobiles,” and “Home Alone.” Like I mentioned in my review of one of his other unproduced scripts, “Tickets,” Hughes hit a chord with young audiences that had never been hit before, portraying teenagers with a darkness that separated his comedies from everything else that had come before them. It’s what made John Hughes John Hughes.

So I don’t know how that all changed. Somewhere along the way, Hughes clearly lost interest in the genre, eventually concentrating exclusively on light family fair. It’s been talked about a lot that John Candy was a good friend of his, and that his death took a huge toll on Hughes, which would make sense. 1994, the year Candy died, is the same year Hughes went back to Illinois and disappeared out of the spotlight. Maybe that death scared Hughes away from exploring the dark side of his material. Maybe a bunch of his original specs were rejected and he lost confidence in himself – forcing him into a series of studio assignments. I think that’s the most frustrating thing about all this, is I’m still not clear if Hughes left that world willingly or unwillingly. Does anybody know? Anybody out there?

Anyway, it’s this very mystery that gets me excited whenever an old John Hughes’ script pops up. And so while the idea behind “The Grigsby’s Go Broke,” isn’t necessarily my thing, Hughes made it an immediate must read.

When we meet Gary and Judith Grigsby, at one of their rich friends’ mansions, they are not described to us, but rather lumped in to one general description that paints each of these upper class suburbanites as “rich” and “well-groomed.” In addition to this strange choice, the Grigsbys do very little in their opening scene besides stand around and listen to other people talk. I’m a big believer in introducing your characters in an interesting way, or at the very least a way that tells us who they are. Lester Burnham in American beauty jacks off in the shower cause his wife won’t have sex with him, then pathetically spills the contents of his briefcase all over the sidewalk on his way to the car. I know who that character is. Watching two characters listen for four minutes doesn’t exactly give me a read on the couple I’ll be following for the next two hours, which was a frustrating way to start a script.

Later on, we meet the rest of the Grigsbys, who live in a mansion of their own. Judith and Gary have a 12 year old stuck up daughter named Wendy (who gets upset when the tempura on her private school’s lunch menu is too greasy), an 11 year old snobby son named Damon (who finds joy in making fun of public school kids), and a four year old anti-christ named Gracie (who orders around the maid and the nanny as if she were Mussolini). This is clearly a family who, because of their extreme wealth, has lost all connection with the real world.

Which is too bad, because things are about to get a lot more sucky for them. Mr. Economy sneaks up from behind and karate chops Gary and Judith’s jobs away. Which would be bad enough. But the Grigsby’s break one of the cardinal rules of being rich, which is to not live above your means! (actually, this is good advice for anybody, regardless of your income. In particular, me) In order to take care of all their outstanding payments, they end up selling everything they own, which leaves them with even less money than Screech. The Grigsbys must then move to an old real estate property Gary bought and forgot about in the neighboring working class town of “Mulletville.”

You’d think that having to write “Mulletville” in your return address would be punishment enough. But this is only the beginning. Wendy regrets dogging her soggy tempura since now her lunch menu consists of a meat the lunch lady can’t even identify. Gary, who used to own his own construction business, must now WORK construction. Poor Judith has to work in a department store, where her bitchy former rich friends come to routinely be bitchy to her. And let’s not forget about Gracie, whose days of having a maid fetch her grapefruit juice are long gone. Now she has to compete with the voice boxes of 20 other kids her age in a, gasp, PUBLIC PRE-SCHOOL!

While the story is pretty straight-forward and the theme is fairly obvious (does money lead to happiness?) there are some astute observations about the ice-cold communities of the rich vs. the supportive and community oriented neighborhoods of the working class. This contrast is played out nicely in a scene where the new neighbors try to surprise the Grigsby’s, digging into their toolbox unannounced in an attempt to fix up their house. The Grigsby’s, unaccustomed to such camaraderie, assume they’re being robbed and call the police.

But watching the characters face the challenges of their new worlds is a bag of mixed nuts. When Gary embraces his job with the work-ethic that made him so successful in the first place, it’s charming, while Damon’s attempts to make friends with the kids he used to scorn feels clumsy. Eventually, a nice (believable) twist gives the family the choice of going back to their old lifestyle or staying here in their new one. They’ve no doubt become better people through this experience, but our society teaches us that money is the end-all be-all. Whether it makes us happy or not, we’re told to grab it if it’s there. So will the Grigsby’s give in? Or have they grown enough to recognize that having everything doesn’t lead to happiness?

While this draft of The Grigsby’s Go Broke still seems to be finding its way, there are some good things about it. It starts with the sugar-coated dictator known as Gracie. Although she’s the world’s biggest 4 year old bitch, her nastiness is endlessly entertaining, which is why her scenes, which could have easily had you rolling your eyes, actually have you lol’ing the most. Also good is the second half of the screenplay, which really begins to shine once the numerous setups in the early part of the script start paying off. And once we hit page 70, we’re on the John Hughes Autobahn, which is good, cause there were times where I wondered if we’d ever leave first gear.

The bad is the way “Grigsbys” handles its characters in the first act, who all come off as nasty, annoying, or a combination of the two. I’m actually surprised Hughes took on such a story because its burdened with a couple of well-known screenwriting “avoid-if-you-cans.” Ages ago a producer said to me, “Don’t make your lead character rich. Audiences don’t identify with rich people.” I used to think that was the dumbest advice I’d ever heard. But in the years since, most of the time I’ve read or watched a rich protagonist onscreen, I realized I didn’t like them. It’s hard to feel sorry for a guy who has his Kleenex boxes stuffed with 100 dollar bills. A family of Richie Riches who take their money for granted then lose all of it? And I’m supposed to feel bad for them?

This is complicated even further by an even bigger no-no, which is to never make your protagonist an asshole. Nobody likes assholes. Nobody wants to root for an asshole. Go ahead, count how many movies you love where the protagonist is an asshole. Do you make it past your right hand? Do you make it past your index finger? And here, every one of the Grigsbys is a giant asshole! So now you have five protagonists who are all rich and all assholes. How do we get on board with that??

Well here’s the thing. Being an asshole is a legitimate and interesting character trait to explore. Because wherever we go on our planet, there are always going to be assholes. You probably work for one right now. It’s just that, most of the time, this role is explored on the antagonist’s side, and we can deal with that, because we always have our nice cuddly protagonist to go back to. But if everybody in the entire movie is an asshole, who do you lean on then?

This leads to a question I’ve asked a million times , but still haven’t received a satisfactory answer for. How do you make your protagonist a big fat dick and still have us, the audience, root for him? To my knowledge, it’s only been accomplished a few times. There’s A Christmas Carol of course. Some would say “Cool Hand Luke.” Although I’d argue that Paul Neuman is way too charming to be considered an asshole in that film. Even in a best case scenario, there are only a few precedents for it working. And even when it does work, it only seems to do so by a hair.

With Scrooge, we sympathize with him because early in the second act, we see that he used to be a good person. This “humanizing” of his bad behavior leads to our sympathy. However, had he had just one more scene screwing someone over, or had the Ghost Of Christmas Past showed up just five minutes later in the film, we may have solidified our opinion that Scrooge was a big bad douche and it didn’t matter what he did from now on, WE HATED HIM! You can see this mistake was made in remakes of the classic, where we don’t quite get on board with scrooge the way we did in the original film.

My point is, that while it’s possible to keep us invested in or even rooting for an unlikable protagonist, you stack the chips against you when you do it. And that’s what happened here in Grigsby’s. There’s something very alienating about these characters when they’re introduced to us, and that never quite goes away. Even when the script hits its stride, you never feel like you know these people.

The Grigsbys has its moments, and I hope to find later drafts of the script where I just know some of these issues have been taken care of, but this draft doesn’t quite have enough meat on the bone.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Don’t forget to entertain us in the first act! Most of Grigsby’s problems can be attributed to the first act. In addition to the character issues, there’s not enough excitement going on . The act is used strictly as a device to set up the characters and the inciting incident (them losing their wealth). Now I’m not criticizing Hughes because he may use his early drafts to get all the logical stuff in, then go back and add all the fun and emotion later. I know a lot of people who work this way. I only bring this up because it’s evident in this draft and I’ve been seeing it in a lot of amateur scripts lately. When you’re writing your first act, don’t get so caught up in setting up all the elements (plot, character, subplots, theme) that you forget to entertain your reader. First and foremost your job is to entertain. So make sure everything you set up in your story is done so in a way that entertains us. It’s very easy to lose sight of this priority, because of all the shit you gotta pack in the script early, but you can never lose sight of this.