Search Results for: scriptshadow 250

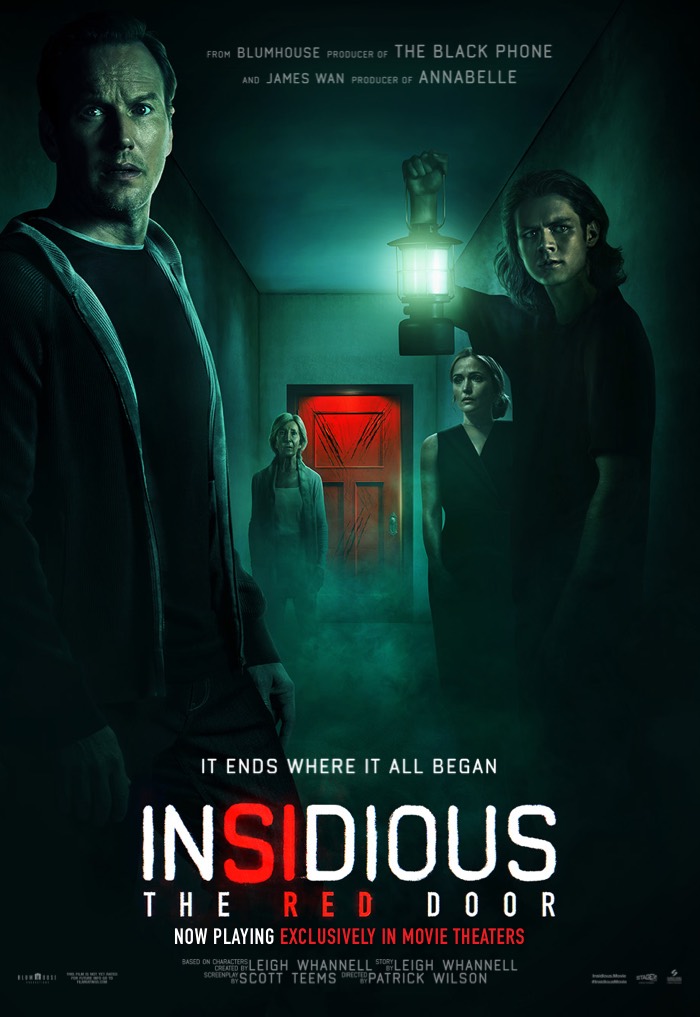

Upon first glance, the weekend box office looks insignificant. The only movie that opened wide was a smaller studio horror movie, Insidious 4.

But I would argue that this weekend’s box office is one of the most important box offices of the year. The box office is its own form of AI, an accumulation of the collective consciousness of every potential moviegoer in the world. And, therefore, when it delivers a number, it is making a point. It is trying to tell us something.

So what is it trying to tell us by anointing Insidious as the biggest movie of the weekend, a small horror franchise that isn’t even associated with an identifiable image?

To answer that question, we must first acknowledge what’s been happening to Disney movies as of late. Disney took over the industry for a decade. It was a super-hitmaker the likes of which had never been seen before in Hollywood. It had Pixar, Marvel, Star Wars, its own animation library, and its live-action animation remakes. The studio pumped out billion-dollar hits like it was Michael Jackson in the 80s.

But everything has changed. Here are some of their recent releases…

Strange World

Elemental

Buzz Lightyear

Ant-Man

The Little Mermaid

Eternals

Why is this relevant? Because Disney drove the business strategy that all the other studios were forced to adapt to in the 2010s. Which was to create super-movies. In the 90s, they would’ve called these “tentpoles.” But Disney took that concept to a new level. Tentpoles didn’t bring in enough money. They wanted SUPER-TENTPOLES – these gigantic movies that created their own orbit they were so big.

The reason was because a super-tentpole could net them half a billion dollars. If you could net half a billion dollars with one movie, why would you concern yourself with making Insidious’s? Insidious may have doubled its budget with its opening weekend take of 30 million bucks. But in “Disney” parlance, that’s a pittance. A 50 million dollar profit when it’s all said and done is weak-sauce when compared to 500 million.

And for a while, that operating procedure worked.

But here’s the problem.

When you make 300 million dollar movies that don’t do well, such as Indiana Jones, you don’t lose 15 million bucks. You lose 150 million. Or 250. Or 350. And while, before, Disney was so successful that they could weather one of these occasional duds, they’re starting to fail a lot more now.

I don’t care who you are. If you’re losing 200+ million a movie? You’re not going to be around for long. And Disney is losing a lot more than they’re winning these days.

Bringing this back to Insidious, studios may have to reevaluate their business strategy. Maybe super-movies aren’t the way to go anymore. They’re too darn risky. And it’s not just because of the pandemic. It’s because they got lazy. They got real real lazy over the last decade and they thought anything with a superhero in it would make a billion bucks. They thought any live-action remake of one of their cartoons would make a billion bucks. They thought any sort of nostalgia would make a billion bucks.

THEY STOPPED INNOVATING.

I say it all the time here. Audiences will NOT EAT EVERYTHING UP. You do have to take some chances. Or, if you’re going to stick with the tried-and-true superhero genre, you have to innovate in *some* capacity. And they’re just not doing that right now.

To be honest, I don’t know if they know how to innovate anymore. When was the last time they tried?

Next weekend’s going to be interesting because Mission Impossible comes out and I don’t know if people are going to see it. It is the definition of something we get ALL THE TIME. And if Fast and Furious is any indication of what to expect, Tom Cruise could be in trouble. By the way, what’s up with Tom? The guy is more concerned with hyping up his competition than his own films!

Following Mission Impossible is going to be one of the weirdest movie weekends I can remember, with Barbie and Oppenheimer opening. To be fair, Oppenheimer is doing exactly what I just asked for, which is to innovate. There hasn’t been a movie like this in decades. Which on the one hand is great. I just don’t know how you pull in a lot of money from a movie that’s not going to have a single female in the audience. Does anyone know a woman who’s going to see this movie?

While unimaginable six months ago, Barbie looks like it’s going to be the film of the summer. It looks like it’s going to be huge. And I *do* think Barbie is trying something different. It looks like it’s hiding very adult subject matter inside a fun summer movie. Which means it’s going to bring in young and old audiences. I have to commend Greta and Margot. I didn’t think they could do it. Yet, here they are. No one’s talking about any movie this summer as much as they’re talking about Barbie.

By the way, for those of you who don’t know, the Barbie movie has been in development for a decade. Ten years ago, Diablo Cody was hired to write the film with Amy Schumer starring. I think we all did a little prayer thanking our lord and savior that that didn’t happen.

But what’s interesting is that Diablo came out this week explaining why their movie didn’t get greenlit and it’s because the studio wanted to deconstruct Barbie and basically crap all over the brand – say all this stuff about how femininity was bad and girls wanting to look like Barbie was bad. And Diablo just couldn’t make it work because that’s not Barbie. How do you make a movie about Barbie where the theme is, “Barbie is bad.” It was impossible to crack.

Whereas it seems, now, they’re making this movie to celebrate Barbie. But it’s also subtly acknowledging that times have changed.

Maybe the biggest surprise this weekend was the conservative film Sound of Freedom, which added another 18 million bucks to its take, allowing it to top 40 mil. This is another genre that isn’t going to get you superhero returns but it’s also not going to strap you with superhero losses if it bombs.

The problem with conservative films in the past has been that they’re too faith-based. Which basically keeps them niche. Cause liberal audiences don’t care about religion. So what Taylor Sheridan introduced was this idea that you could play to other more profitable aspects of conservative beliefs (justice, survival, connection to nature, family), the kind of stuff that works better inside the feature fictional format.

If more conservative writers realized that, there’s a huge market to be tapped there, as Sound of Freedom has proven.

This could be the future of the box office if these giant movies keep failing. Cause it’s not just Disney. It’s WB as well. Superheroes are no longer teflon. Spider-Man, maybe. But that’s because he’s the best superhero. So, of course his movies are going to do well. But everyone else? They’re in trouble.

Which means getting smarter and exploiting these neglected crevices in the market. Or just write horror films. Cause horror films always do well.

Speaking of horror, I bucked up and got MGM Plus so I could watch that show, “From.” A few of you told me it was awesome. I finally listened. I watched the pilot and it was indeed, very good.

For those who don’t know, the show is about this town in the middle of nowhere that people are stuck in. If you drive out on the road, you always loop back to the town automatically. What’s interesting is that people keep showing up. Every couple of weeks, a new person or family will drive into the town, lost, wondering where they are. When they’re told they’re forever stuck here, they of course try to leave, only to keep looping back into town. It’s a fun little premise. And it also has these monsters that come out at night, which forces everyone to be home by nightfall. It’s one of those rare gems that treats their setup with such respect that it doesn’t come off as cheesy.

I don’t know if you remember that disaster on NBC called La Brea about the people who fall into a wormhole and end up in Los Angeles a million years ago. If you watch “La Brea” and then watch “From,” you’ll notice the sophistication in the writing is night and day. One understands how to do their genre premise right. The other makes almost every mistake in the book.

Anyway, I loved the pilot episode. I’m going to keep watching. If you want to check it out, the first 7 days of MGM Plus are free.

But, despite my overall love for the pilot, I did want to highlight one major mistake in “From” only because I see this in screenplays ALL THE TIME and it drives me insane. I call it “dialogue tunnel vision.” Dialogue tunnel vision is when you get so determined to write a certain line of dialogue, that you’re unable to realize how inappropriate the line is within the context of the moment.

So, in the pilot, this lost family in an RV rolls into the town. They’re confused. They coulda swore they were supposed to run into a highway by now. And it just so happens that they arrive during a town funeral. Two people were killed last night by the monsters.

The RV parks next to the service, which is ending. As the townspeople all walk away from the service, the teenaged daughter in the RV opines to her family, sarcastically, “They seem like a cheery group.”

Now, I want you to think about this line for a second. Cause this is the epitome of dialogue tunnel-vision. I know exactly what the writer was thinking. They were thinking, “Let’s establish that something weird is going on in this town. The people aren’t right. They’re not acting normal. Let’s have our outsiders vocalize that.”

But the writer had so much tunnel-vision in establishing that reality with this observational line of dialogue, that he completely overlooked the fact that ALL OF THESE PEOPLE WERE JUST LEAVING A FUNERAL!!!! Who has ever looked cheery after a funeral? What the daughter is saying, objectively, makes zero sense. Why would you expect anyone to be looking cheery right now? Hence, dialogue tunnel-vision.

I’ve got a couple of other examples for you. In Gareth Edwards’ first movie, “Monsters,” about these giant monsters that lived in the jungles, we watch this couple who has to travel through one of those jungles. Everywhere you looked, in that movie, there was a sign that said, “Warning: Giant Monsters Ahead.” Then, halfway into the jungle, the couple hear this loud terrifying gurgling grumble off-screen and the husband says to the wife, I kid you not, “What was that?”

IT WAS THE MONSTERS!!!!!!!! ARE YOU DENSE OR SOMETHING????!!!!!

But, again, Gareth Edwards wanted that line in there. He wanted to, I don’t know, create suspense or something. He wanted that quiet scared moment where his characters tried to figure out what was making such a strange noise, despite the fact that the whole movie you’d written up to that point told us exactly what it was.

And then, we can’t leave the dialogue non-master, George Lucas, out of this, who, in Attack of the Clones, when Padme’s double lays dying on the ship platform after her ship blew up, Padme runs up to her and her double, in her last breaths, says, “I’m sorry your highness. I failed you.”

Uhhhhh, no you didn’t fail her. You actually did exactly what you were supposed to do!!! You made the bad guys think you were Padme, so that they tried to kill you instead of her. But Lucas was so zoned in on delivering that line, he couldn’t see the forest through the trees.

So just be aware of this, please. Place yourself in the reality of the moment and ask what would really be said in that moment. Don’t just write dialogue that you wanna write. Cause it may not stand up to the scrutiny of the situation.

What’d you watch this weekend?

It’s time for an apology.

Or is it time for one of those apologies that aren’t really apologies? You know the kind I’m talking about. The kind where you apologize to anyone who was potentially offended by what you said? But not for what was actually said, which would denote the act that required the apology in the first place.

Last month, I laid the hammer down on Dungeons and Dragons. I said it was a dumb idea to ever think that an IP with such non-specific properties could ever hope to pull people into the theater.

Well, when I was going through my streaming setup, I noticed that Dungeons and Dragons was now available on digital. And not only that. It was available on Paramount Plus, which, apparently, I have! Believe me, I’m just as surprised as you are. Those crafty little streamers have successfully wiggled their way into my financials to ensure that I will never stop paying their monthly fees for as long as I live.

Anyway, I started watching D&D, expecting to turn it off within a few minutes. Which I did. But then I couldn’t sleep so I turned it on again. And it was pretty good! I immediately understood what they were going for. They were making the big budget version of The Princess Bride. The humor was similar to that film almost to a T.

And outside of the perpetually-seems-to-hate-her-job-more-than-life-itself Michelle Rodriquez, all of the actors did a really good job. I wish I could win a “Hang out for a day with Chris Pine” contest. The “It” girl was also in it. She’s always good. The guy who plays the terrible sorcerer was really good. All contributing to a breezy good time.

However!

Was I actually wrong?

The movie was good. I was wrong to assume that it wasn’t without seeing it. But it didn’t do well at the box office. And not many people seem to know anything about it. So what does that mean? More specifically, what does it mean for screenwriters?

I’m going to say something controversial here which I may or may not apologize for at a later date: If you execute an amazing screenplay but it’s a weak or bland concept, it doesn’t matter. It doesn’t matter because people won’t want to read it. If they don’t see your film or don’t read your script, they’ll never find out that it’s good. So if they never find out it’s good, is it good? Does a tree fall in the forest?

Someone just sent in a logline consultation this weekend frustrated by the fact that they’d sent out 70 queries and not a single person had requested the screenplay. Which is why they wanted my help. Maybe I could work my magic on the logline and it would all of a sudden have the entire town bidding on it.

But the logline didn’t have a hook. Which is something the writer knew. They weren’t ignorant to this fact. But after discussing the concept over a series of e-mails, I told him, this just isn’t a “queryable” script. It’s a straight drama without a clear hook.

For those scripts, you got to win big contests or get multiple 9s over on the Black List. Then, when you query, you query the accomplishments. If you say you were a finalist in the Nicholl, most managers will request your script without even looking at the logline. Cause you’ve already proven that you can write. Which is the main thing they care bout.

Without that, I told him, you might as well query managers with: “Trust me, I can write.” Cause that’s what you’re doing when you query people with a logline that doesn’t have a clear hook.

The other option is to direct the script yourself. Then you don’t need anybody to like your script. Although now the onus is on your directing because you need to prove you can direct in order for someone to finance your film. Which has its own set of challenges. But it can be done. It happens all the time.

Segueing back to Hollywood, you can feel the fear in the theatrical air. Cause trust me. Paramount didn’t want to make a Dungeons and Dragons movie. They didn’t! They know it’s a weak property. But it’s still one of top 75 IPs out there. And if you don’t have superheroes – which Paramount doesn’t – you have to scrape the bottom of the IP barrel and hope to strike gold. I love mixing my metaphors.

It’s even infecting the king of the industry – Disney. The 3-day haul on their latest live-action remake, The Little Mermaid, was less than 100 million. That’s not a good opening for a Disney film. Especially one that cost 250 million. Plus another 100 for marketing.

Hollywood, now, is depending on these weird outliers, movies such as Top Gun: Maverick and Avatar: Way of the Water to make the bulk of their money. One franchise took a decade to come out with its second film. The other one took three decades! That’s not a financial plan Hollywood can get behind.

And Disney isn’t doing themselves any favors. If they took the Top Gun route and stayed out of anything that might create controversy, then everyone would come to their films. But they’re doing weird stuff now that makes parents nervous about what exactly is in the movie. And if you have nervous parents, guess what? They’re not going to take their kids to your movie.

And I understand the other side. The side that says, do what’s right over what makes money. The problem is, Disney is the embodiment of the four-quadrant studio. That’s what they do better than anyone else, which is why they make so much money. So if you take a quadrant or two out of there, they’re not Disney anymore. They’re Paramount. They’re Sony. And if they’re okay with that, then go for it. But if they want to remain the sole superpower, they have to think long and hard about some of these decisions they’re making.

Despite these troubling theatrical questions, I’m still looking forward to seeing a number of movies in the theater this summer. The Flash. Indiana Jones. Mission Impossible. Oppenheimer. Maybe even Barbie! It depends on what people are saying about it.

By the way, did anybody see the end of Succession or Barry. My unofficial plan was to wait it out so I could binge them all at once. But then I started hearing all these spoilers. THANKS INTERNET! What do you think? Is it worth getting back into them?

By the way, did I ever apologize?

If not, I apologize to anyone who was offended by my non-apology.

I’m always looking for that screenwriting angle to an industry story.

So when I see that Dungeons and Dragons couldn’t quite manage 40 million dollars on its opening weekend in an industry where big-budget films need to make 60 million dollars *AT LEAST* to be considered a success, I ask, “What can we learn from this?”

Or when I see that last weekend’s belle of the ball, John Wick 4, dropped a significant 62% in its second weekend (John Wick 3 dropped only 56% in its second weekend), I openly wonder, “Is there a writing issue here?”

Let’s start with Dungeons and Dragons. I don’t think it matters what you do with this property – it’s not going to work. The primary problem is, when I say, “Dungeons and Dragons” and ask you what images come to mind, I’m guessing the answer is “nothing.” Because it’s not like Star Wars where you immediately think of lightsabers. Or Lord of the Rings where you have clear images in your head of creatures like Gollum. Or Marvel, where you imagine a dozen different superheroes.

Dungeons and Dragons literally makes you think of a generic looking dragon. Or a generic looking cave. Or a generic looking orc. There’s no specific imagery. And specific imagery is what sets IP apart from original ideas. If I pitch you a Peter Pan movie, that’s going to put a specific image in your mind, compared to if I pitch you a Flyborne Felix movie.

That makes Dungeons and Dragons one of the rare instances of IP that operates like an original idea. It’s not bringing IP value to IP. Which is the whole point of IP!

Another problem with Dungeons and Dragons is the studio’s attempt to turn it into a comedy. I know a few people who play the game. I don’t personally play it. But my understanding is that it’s not a comedic game. It’s more of a strategic game that the people who love take seriously.

If superhero movies have taught us anything, it’s that the closer you draw from the source material, the better. By making the Dungeons and Dragons movie highly comedic, aren’t you moving away from the source material? Are Dungeons and Dragons players the types who say, “Man, did you hear how funny they made Dungeons and Dragons? I gotta see that. It’s such a good idea to make it funnier!” I’m guessing nobody said that.

Which goes back to the truth of the matter, which is that this isn’t a solid enough property to build a franchise on. It just isn’t. And the box office bore this reality out. That’s something every writer should be aware of: Is my idea good enough to write a script about? Because, if it isn’t, it doesn’t matter how good your execution is. It doesn’t matter what your angle is. Your idea was never strong enough to support a feature film.

Which is why I can complain about how Dungeons and Dragons shouldn’t have been so comedic but I know that even if they’d gone the serious route, it was still going to tank. Cause it’s built on top of a weak foundation. There’s not a single recognizable character or creature here. So it’s not surprising that D&D, like its predecessor in 2000, will fade into the night, never to be remembered again.

Our second big movie lesson comes from John Wick 4’s big second weekend dip. A 62% drop isn’t as bad as Quantumania’s 70% drop. But like I said above, it’s a fairly significant drop compared to the third film, and this from a movie that’s gotten a lot more attention. So what’s going on here?

No, you are not experiencing deja-vu. This move is happening for the 980th time this movie.

No, you are not experiencing deja-vu. This move is happening for the 980th time this movie.

At first I thought it was the length. That’s what she said. But Avatar 2 and its 9-hour running time becoming one of the highest grossing movies ever put that theory to rest. But I do think time is a part of the problem, specifically REPETITION. This is something I see all the time in weak scripts, which is the repetition of things we’ve already seen.

John Wick’s biggest weakness is its insistence on fighting and shootouts that repeat the same moment over and over again. I mean, how many times did we see John Wick grapple with someone, shoot him a few times, kick and punch, before taking them down and shooting them to death. There literally had to be 75 kills that played out in the exact same way.

If they would’ve cut those in half, not only is the movie going to move faster, but the kills then take on more significance, since the rarer something is, the more valuable it is.

For any movie, the opening box office of the film is based on five things – the concept, the directing, the IP, the marketing, and the cast. But the second weekend is based on one thing: THE WRITING. If the writing is good, everybody who saw your movie on that opening weekend will tell their friends and talk it up on social media. That’s when you get small second weekend drops. If you get a big dip, the issue is the writing.

This is not surprising for the John Wick universe, as this property has never been about the writing. Even John Wick is more of a movie star persona (Keanu Reeves) than a character. We don’t really know anything about John Wick other than he likes to shoot guns. He’s similar to Ethan Hunt in Mission Impossible. The average person who watches Mission Impossible doesn’t even know Ethan Hunt’s name. They know him as Tom Cruise.

Movie star driven movies can work. I’m not bashing them. The problem becomes when you rest on that and don’t think you need to write as good of a script because of it. A lot of these big movies fall into that trap. John Wick 4 dropped the ball there. They became so obsessed with the production design and the fighting choreography that no one thought to say, “Hey, maybe we shouldn’t have 6000 fights that look exactly the same.”

Cause I’ll be honest with you. I almost didn’t give John Wick 4 a passing grade. Specifically because it was so much of the same moment over and over.

The good news is, we’ve got “Air” coming up next weekend. It’s a great script that broke into my Top 25. The movie’s supposed to be just as good as the screenplay. Previously, I only had the review inside a newsletter. But for those who don’t receive my newsletter (e-mail carsonreeves1@gmail.com with subject line: NEWSLETTER to sign up) I’m including the review below, when the script was titled, “Air Jordan.”

Genre: Sports Drama

Premise: In 1984, an out-of-shape bulldog of a sports executive at a small shoe company called Nike attempts to sign the hottest basketball player out of college, Michael Jordan.

About: This is that big splashy deal that just came together. Ben Affleck will direct (and star). Matt Damon will star. Amazon is the buyer. This is a huge win for the writer, Alex Convery, who doesn’t even have a produced credit yet. I’ve reviewed a couple of his scripts, Bag Man and Excelsior, both of which I liked. So this guy’s got the goods. No doubt this project came together in the wake of the success of HBO’s Winning Time.

Writer: Alex Convery

Details: 104 pages.

As someone who grew up in Chicago during the Jordan era and who used to routinely go to the old Chicago Stadium to watch the Bulls play, I can say that I am both excited and not so excited for this script.

I’m excited because I get to go back in time and relive some powerful memories. I’m not excited because I’m not convinced there’s a story to tell here. When you’re going so deep into the Jordan mythology that you’re covering some orbiter of an orbiter of Jordan’s sun, you’re testing the limits of what people care about. I mean, what’s next? The story of Cher’s first hairdresser’s assistant?

Then again, isn’t that all scripts? You don’t care until you do. Let’s see if we do!

45 year old slovenly Italian-American Nike shoe executive Sonny Vaccaro is looking at an uncertain future. He works in the basketball department for Nike, a tiny shoe company that specializes almost exclusively in its CEO’s first love, running.

In 1984, Nike doesn’t care about basketball because nobody cares about basketball. The NBA championship isn’t even broadcast live! So it makes sense why Sonny’s boss, Phil Knight, is only giving the basketball department 250,000 dollars to sign three rookie basketball players to shoe deals.

Now you have to understand, back then, there was no such thing as a personalized shoe. You wore whatever shoes the companies made. And Adidas and Converse had much cooler shoes than anything Nike had created.

While the rest of his team is resigned to signing scrub basketball players, Sonny is obsessed with getting Michael Jordan, a huge problem because Phil won’t give him the money to sign him and Jordan’s agent, David Falk, says Jordan doesn’t even want to meet with Nike. He’s set on Adidas.

This is when Sonny has his epiphany: A PERSONALIZED shoe built around the player. They’re going to mold it to his foot. They’re going to design it the way he wants it designed. And they’re going to give it a name – Air Jordan – that will work to market him while he’s playing.

Now all Sonny has to do is figure out a way to get in front of Jordan and make his pitch. When all avenues fail, Sonny heads out to North Carolina to talk to Jordan’s parents. Used to slimy tactics from agents and executives at this point, they don’t want any part of Sonny. But while Sonny can’t dunk from the free throw line, he does have a superpower of his own: HE NEVER STOPS TRYING. And he will pursue Jordan til the bitter end.

The first thing that comes to mind when I read a script like this is a rarely talked about writing tool, which is audience dramatic irony. Traditional dramatic irony is when the audience knows something the main character does not. Audience dramatic irony is when the audience knows more than every single character in the story. Titanic is an example. We know the ship is sinking. They don’t.

Audience dramatic irony can be played to all sorts of effect and is perfect for scripts like this, where the audience already knows a bunch of details. For example, there’s an ongoing discussion within Nike on whether Michael Jordan is worth spending their entire basketball budget of 250,000 dollars on. We, of course, know that Michael Jordan will be worth billions of dollars to Nike in the future. So it’s funny to watch them squabbling over such a minuscule number.

Or you get moments like Sonny meeting with the general manager of the Portland Trailblazers, who infamously passed on Michael Jordan with the number one pick (The Chicago Bulls would end up picking him at number 3). Sonny is trying to figure out from the guy why he passed on Jordan, try to get a little intel to help him decide what to do. After a while, the GM gets annoyed with Sonny’s line of questioning and says, “What, you think I’m going to be remembered as the man who passed on Michael Jordan? Come on, Sonny. Players come and go. No one’s remembered for just one player.”

But the big reason this script works and the reason it will be a hit is because of one of the most basic screenwriting principles in the book – IT’S GOT A MAIN CHARACTER WHO WANTS SOMETHING REALLY BADLY AND HE GOES AFTER IT WITH ALL HE’S GOT.

This whole script is about a guy determined to get something – sign Jordan. That’s it. We always feel like we’re moving forward because every interaction Sonny has is for that larger goal. This is when scripts really cook, when you institute this simple principle. It’s when characters have muddled motivations and don’t really care about what they’re after that scripts become boring (later Scriptshadow Edit: look no further than the third season of The Mandalorian).

Once you establish that drive to succeed, you simply make succeeding as hard as possible. Sonny’s boss, Phil Knight, won’t give him the budget he needs to sign Jordan. Jordan’s agent, David Falk, tells him don’t even try. Jordan’s signing with Adidas. Jordan’s parents tell Sonny, “He’s not going to sign with you. Give up.”

What readers and audiences like is determined characters going up against giant “no’s” who then overcome those no’s one by one. The reason audiences connect so closely with this formula is because most people in life get beaten down by obstacles. At a certain point, they give up. So to see someone not give up is wish-fulfilling and life-affirming. Because they say, “Well, this guy can do it. Why can’t I?” And they leave that script or that movie charged up.

An ancillary benefit of this is that many of your scenes will write themselves. Think about it. You have a guy who needs something badly. You have a line of characters who want to keep him from getting it. This ensures that EVERY SINGLE SCENE is set up to succeed. Because the best scenes tend to be when someone wants something and someone else doesn’t want to give it to them. Writers do mental cartwheels trying to find scenarios that will allow them to use this formula in as many scenes as possible. However, when it’s baked into the premise, like it is with “Air Jordan,” you just show up for the scene “room” and the chairs and tables have already been arranged for you.

It’s also a really fast script to read because it’s all dialogue. And this is something I tell writers all the time: If you’re good at dialogue, write scripts where all anybody does is talk because those scripts read the fastest. And “a fast read” is crack to a busy industry person.

I tried reading a professional script the other day and it was like walking through quicksand with boots made of concrete getting through those pages as it was all really dull and elongated description. This is the opposite. Every scene is the dialogue-friendly character of Sonny walking into a room and trying to convince another character of something.

Totally see why Matt and Ben fell in love with this. Air Jordan is a slam dunk.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[xx] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Strike when you’ve got a screenplay that exists in the same world as something that’s hot right now. A script about otters is dead in the water until, one day, a movie about beavers clears 100 million in its first weekend at the box office. Air Jordan, no doubt, started getting pushed heavily around town once the documentary, Winning Time, became a hit. If you’ve got anything that’s similar to a movie or show that everyone’s talking about, call every contact you know, no matter how peripheral, and pitch your script to them. If it’s anything close to that hot new successful thing, they’ll want to read it.

What I learned 2: For the really savvy screenwriter, track shows that are similar to your idea BEFORE THEY GET ON AIR. You are waiting for them to do well so that when they do, you have already lined up your ducks. I bet my Jordan memories that’s what happened here. They saw that Winning Time was coming out and built a campaign around sending that script to everyone once the buzz for the show ratcheted up. You’re playing with the big boys here. Do your prep work and stay ahead of the curve.

Today we get a pilot script from Hollywood’s newest golden child screenwriter

Genre: TV Pilot – 1 hour – Horror/Slasher/Sci-Fi

Premise: Set 15-20 years in the future, a group of high school kids ensconced in future technology are shocked when one of their friends is murdered, seeing as murder rarely happens anymore.

About: Today’s pilot comes from Hollywood’s screenwriting wunderkind, Shay Hatten, he who has basically taken over writing all the John Wick movies. He wrote this pilot in 2018 for the SyFy channel. They cast the show and shot a pilot but it was apparently so bad they didn’t go to series with it. Hatten was on my list of Top 10 future great screenwriters in Hollywood.

Writer: Shay Hatten

Details: 54 pages

We’ve got ourselves a Shay Hatten script today.

Hatten is known for his big energetic writing voice, which he definitely brings to today’s pilot. Hatten, who is not shy about his desire to emulate his hero, Shane Black, gives us all sorts of 4th-wall breaking action to digest in (Future) Cult Classic.

“If this scene doesn’t make every single person watching it vomit, I quit. Andy’s Dad’s guts have been, like, forking splorked all over the Goddamn place.”

Since I know some of you hate that writing style, tread carefully going forward.

The year is 2025 or 2030 — somewhere in that range – and 17 year old cool rebellious girl, Bree, is heading to her best friend, Andy’s, place so they can go to the first day of school together. The two are besties times a thousand, although you kind of get the impression Andy loves Bree.

Needless to say, he’s not happy that Super Cool Guy, Henry, has lowered himself from his cool guy pedestal to date Bree. We know this wasn’t easy because the social credit app the teens use has lowered Henry’s popularity out of the top 1%. Meanwhile, Bree and Andy are the two lowest-ranked students on the app, on purpose. They do bad things to stay at the bottom.

After a few oddly injected “Trump is evil” remarks that didn’t have anything to do with the story, all the students put on their virtual reality goggles, where they’re then transferred into a virtual environment, where their principal makes several announcements about the coming school year.

After this VR excursion ends, the principal tells everyone to meet him in the auditorium as he just received some devastating news (I can’t emphasize how clumsy this is – after the principal greets them in the VR world, he then says he wants to greet them in the real world, creating two scenes in what easily could’ve been one!). The principal then announces that one of the students (who we met earlier at a party) has been killed.

What we eventually learn is that some masked killer is running around killing people. It’ll be up to Bree and her friends to figure out who it is. Of course, they’ll also be hoping it isn’t one of them.

I’ve seen some bad ideas before. But this is up there.

A horror slasher story set in the future with the unofficial tone inspiration being Back to The Future 2. Who needs a regular horror show when you can integrate virtual reality, social credit apps, and hoverboards?

I’m sorry but horror and the future don’t mix.

Let’s not forget the last horror movie that tried to be futuristic. Demonic? Remember that masterpiece? There were a confirmed 13 deaths from the 100 people who went to see that movie in theaters. Cause of death? Boredom.

Horror is the one genre that gets better the further back in time you go. If you go back just 30 years, we couldn’t call anybody when we were in trouble. We just had to deal with it. That alone makes for horror situations that are a thousand times scarier.

I just watched Silence of the Lambs again (yes, for my dialogue book, in case you were wondering) and I was thinking that great scene where Clarice accidentally visits Buffalo Bill’s house couldn’t have been written today. Her boss would’ve called her to warn her. And, if she didn’t answer, he would’ve texted, which she would’ve checked.

But things get really scary if you go back 50 years, 100 years, 150 years. In those days, not only was everything spookier, but you were really on your own if you were stuck in a bad situation.

The badness of this pilot didn’t stop there, though.

It’s set 15 years in the future and we would occasionally flash back eight years to when Bree was a kid. So now we’re flashing back despite the fact that this show’s flashback is still our present’s flash-forward. It’s just weird. It twists your mind in all the wrong ways. You’re thinking about things that have nothing to do with the story itself, which means the suspension of disbelief is constantly being broken.

Shay was probably frustrated because he was trying something different here. And isn’t that what we’re told to do as writers? Be unique. Show a new voice. Find a different angle. Be subversive.

Then we do all those things and everyone’s like, ‘well that was dumb’ so we shrivel up into a ball and spend three weeks eating 5 dollar donuts from Slider’s even though they make your tummy hurt cause all the yeast is natural and therefore expands way further than all that fake yeast and you promise yourself you will never ever try something original or eat donuts again. You’re going to play by the rules from now on.

Look, I’m not telling you to play it safe.

But “different” is a dicier path. It has a much higher failure rate. That’s because if something hasn’t been tried already, it’s not because you’re the one genius who came up with the idea. It’s more likely because it’s been tried before and failed badly, so everyone forgot about it.

This begs the question, how does a writer recognize that they have a bad idea?

Well, the best way to find out is to poll the idea with people who have no connection to you. Put your idea here in the comments and see what commenters say. Don’t listen to the commenters who are your friends as they will likely be nice to you. Look at the people who you have no connection to. They’re going to be the most honest.

If the ratio of dislike to like is around 5 to 1, you’ve got a bad idea on your hands. Anything worse, you’ve got a really bad idea on your hands. You want to be closer to the 4 likes for every 1 dislike ratio.

But let’s say you’re private about your ideas and don’t want to post them on the internet. What then? If you truly want to figure it out privately, you need to be extremely honest with yourself. Start by asking, is writing this script like pulling teeth? Does every scene and moment feel forced? Do you dread writing the script because it’s always difficult to come up with pages?

Deep down, do you have this constant feeling that the story doesn’t work?

If so, you probably have a bad idea. I’m not going to go so far as to say this is true all the time. Some genius works are hard to write. But I think we all know, deep down inside, if something is working or not. And if you’re unsure, you always have me. You can get a consultation and I’ll tell you straight up, if you genuinely want to know, whether the idea works or not. You can even get a logline consult done BEFORE you write the script to potentially save yourself a lot of time.

Also keep in mind that you can pivot. You don’t have to completely abandon a script if you love the idea. Sometimes it’s a matter of changing the main character POV. Sometimes it’s about changing genres (from a slasher to a mystery, or a drama to a horror). Sometimes you haven’t unlocked the best angle to tell the story from yet.

When it comes to today’s story, it does start to come together a teensy bit towards the back end of the pilot. Once we start looking into Emily’s murder, there is a slightly fresh perspective we’re exploring this genre from – this idea that a murder has been committed in a world where murder has basically been eradicated.

But, again, the tone is so off here. The comedy and the horror don’t mix organically. You throw in the “Back to the Future 2” future speculation stuff (“Zoinks! There’s one of them hoverboarders!”) and it gets even jankier. The story just doesn’t know what it is.

And I could totally see this playing out when they tried to shoot the thing. I could see five actors playing five different tones. That’s how poorly constructed this mushy mythology is.

I struggled through this one from the get-go. I’m surprised I was able to make it through the whole thing, to be honest. It was that bad.

Script link: (Future) Cult Classic

[x] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: When it comes to comedy-horror, the comedy has to be organically built into the story. That’s why yesterday’s comedy-horror film, Deadstream, was so good. The main character was an annoying Youtuber. So that’s where all the comedy came from – him being one of those annoying Youtube personalities. When you’re just trying to add comedy to add it, cause you want to, you get today’s pilot. Everything feels forced.

OFFICER KIPPER

Peyton, the boyfriend. It’s his SnapStream feed.

MOSCOVITZ

Is that like SnapChat?

Kipper stifles a laugh. Moscovitz glares at him.

OFFICER KIPPER

Sorry, just– SnapChat was over ten years ago. This is totally different.

Ooph. This is what passes for humor in this script. Forced humor is the worst humor.

What I learned 2: Unless you have an amazing horror idea that needs to be set in the present, I highly suggest you set you horror script at some point in the past.

It’s always fun to see Scriptshadow veterans have success. Kevin Bachar is a former Amateur Showdown winner. He credits the win and the subsequent review as a big learning experience for him. Since then, he’s gone on to write a script, The Inhabitant, a modern take on serial killer Lizzie Borden, that he got optioned and eventually made. The movie is out right now (!!!), both in theaters and on VOD. Kevin is a documentary filmmaker who grew up in Queens and attended Brooklyn College.

SS: How many scripts did you write before something happened with this one?

KB: The first script I wrote was a horror film entitled – The Peak of Fear – which I submitted to Amateur Showdown, way back in 2014. Although it won, it didn’t get the coveted “worth the read” Script Shadow seal of approval. But it was a great exercise in getting notes and applying the ones I thought worked and discarding those that didn’t. The Inhabitant, which was originally titled – Blood Relative – was my third script. It was also a conscious decision on my part to write something easy to produce and relatively low budget. I know we’re told all the time not to chase after genres and we should write what you “love”, but the truth is no studio or producer is really reading scripts from unknown writers for big budget pics. The best way into the industry is through horror/thriller with a hook or twist. Mine was the attachment of the Lizzie Borden myth set in modern times.

SS: I know you are a big reader of the site. Can you point to anything you learned on the site in particular that helped you with this particular script?

KB: I’m an avid reader, and have been since I started screenwriting. I remember one bit of advice you gave in regard to plot, where you used the metaphor of blowing up a balloon. The script should be continually blowing up that balloon until it keeps getting bigger and bigger until you know it’s going to explode, but you keep blowing, getting it to the absolute stretching point, and then you’re wondering how many more puffs can it take until you bellow out one more breath and then – BOOM.

SS: When did you finish the script?

KB: I finished the script in 2015 and placed it up on the BlackList website. It ended up getting a number of the coveted 8s and was eventually highlighted as a featured script on the site. Just to be clear, this is the BlackList website, not the annual list that comes out and you review scripts from.

SS: How did you get your manager (or agent, or both)? And did that happen with this script or a previous one? If a previous one, how many scripts ago and what was the script about?

KB: The manager that first helped get The Inhabitant (Blood Relative) rolling, found me via the BlackList website. They read a number of my loglines for scripts I had on the site and they thought they were very producible. I think it hits something you mention all the time about the importantance of loglines and is your idea a movie. Not to be a downer but too many times I’m reading loglines or ideas mentioned on Script Shadow and they are too naval-gazing inward dramas or high-flying space operas that aren’t going to get serious attention from any manager/agent.

SS: Why do you think it was this particular script that got made (as opposed to your previous scripts)?

KB: My previous script, the aforementioned – Peak of Fear, was horror, but was not what you’d consider low budget. It wasn’t in any means a high-budget but it wasn’t going to be less than 2 million. The Inhabitant was not special efx heavy and could be done at a lower price point. It also had a teenage lead which is one of the key selling points for horror – since that’s the biggest audience for the genre.

SS: When was the script purchased/optioned?

KB: The script was eventually optioned in 2019. So, I wrote it in 2015 but it didn’t get optioned until 4 years later. I can’t stress enough that you have to be willing to play the long game in screenwriting.

SS: When and how did the money come through?

KB: The option money came through when the option was signed and then the payment for the full script came in when we began principal photography. I know everyone wants to know numbers but that’s not going to happen, sorry but as they say – That’s personal. And to be honest it has no bearing on breaking in and what you might get paid for your work. It all depends on the budget, studio, producers and where you shoot it.

SS: A lot of scripts get written. Rarely does a script get made. What would you say was the most important factor in this script getting made? Who, involved in the process, was the most important person in getting the movie made?

KB: I think there are a few key players who helped get The Inhabitant made. The manager I mentioned earlier also managed a director who loved the script. I worked with the director and created mood boards and a proof-of-concept trailer or a rip-o-matic (see the one Rian Johnson did for Looper.) The director eventually dropped out, but it helped make the project real. The producer of The Inhabitant, Leone Marucci, was the next huge driving force, as any producer is to get a film made. It’s kind of obvious, but the film doesn’t get made without Leone pushing it forward because he believed in it. He actually contacted me about another script which was under option and I told him about The Inhabitant, and that it was available. He read it and loved it. Which brings me to the final most important factor/person to get the film made – the screenwriter. I was always pushing it forward and committed to spending time and money to get it made. On my own dime I flew out to Los Angeles to take meetings with the director and Leone (pre-covid 2019) which showed that I was serious about the film. I also spent time and money creating and cutting the proof-of-concept and mood boards which were really helpful in getting people to understand what the film could be.

SS: I believe this started as an independent project right? Can you explain to me how it ended up at Lionsgate?

KB: It was an independent production, but when the film was finished it was then taken to various studios – big to mid – and both Lionsgate and Gravitas Ventures partnered in the release.

SS: I noticed you’ve had a long and successful career as a documentary filmmaker. I suspect some writers might think you had an advantage being in the industry already. Possibly gaining industry contacts from that world. Did your career in the documentary world help you succeed in screenwriting at all?

KB: The truth is my doc career meant nothing to the fiction/movie world. It gave me an interesting story at meetings but not one of my documentary connections at Discovery, Nat Geo, etc intersected with the feature world. I let people know this all the time because they want to put up these invisible fake walls and in the end it comes down to their writing. My doc work didn’t help me win the Page Awards, twice semi at Austin, win Final Draft Big Break for romcom and win Screencraft’s Action/Thriller contest which had Steve de Souza, the writer of Die Hard, as one of the judges. If you write a great script and get it out there through Script Shadow or contests or queries then it will get read and that’s the truth. Sorry if I’m ranting, it’s just I’m so tired of hearing the same old “woe is me” lines. Just write, and write great scripts.

SS: With everything you’ve learned, what would be the biggest advice you’d give to writers on how to write a script and get it made into a movie?

KB: I think you need to read what is getting made and ask yourself a simple question – “Is my writing this great?”. Go read Taylor Sheridan’s Wind River – does your script sound like that? Move like that? Draw you through the page and onto the next? Read any movie that got made over the last 20 or so years and compare your writing to theirs. I know when I started my writing was nowhere near what was being produced. But I’m a perfect example that you can get better, much better.

SS: I tell writers to do this as well but I’ve found that, often times, writers just aren’t able to see how professional writing is better than theirs. Most writers I encounter, actually, think their writing is better than the movies getting made. So is there a more specific way to judge your writing against professional writing?

KB: To be a writer, a writer who will sell that novel, short story or screenplay, you have to be able to be 100% subjective on your own writing. I think this might be one thing that can’t be taught. You see it a lot of times on Script Shadow when people start endlessly defending their script when people start to give criticisms. They’re never going to improve. I also think, having a real objective sounding board is key. Having your friends or family read it means nothing and really offers you no real feedback. Even a friend who’s a reader or producer, because in the end they’ll never give you their real reaction if the script isn’t good. Also, I know it’s controversial but screenwriting competitions/fellowships can offer you a real benchmark for your script. The Inhabitant – as mentioned, received numerous 8s on the BlackList, it was semi-finalist at Austin, a top %15 at Nicholls amongst other placements. Also, winning Amateur Showdown on Script Shadow years previous told me that I had some talent as a writer. Too many writers never get their work out there to see if it in fact is professional level.

Now go and watch The Inhabitant!

$$$ – SUPER DEAL ON SCRIPT NOTES! – $$$ – I’m letting TWO MORE people in on that newsletter deal. 4 pages of notes on your script for just $299. That’s 200 dollars off my regular rate. E-mail me at carsonreeves1@gmail.com with the subject line, “DEAL,” and you’ll be first in line to reserve a slot. If you’ve got a TV pilot, I can take another 50 bucks off the price. Take advantage of this! You never how long it will be before the next deal!