Search Results for: scriptshadow 250

Today’s script would’ve easily won Tagline Showdown!

Genre: Horror

Premise: A group of friends find their lives disrupted after experimenting with a new drug that first makes them hear something, then see something, then become hunted by something.

About: This script finished pretty high on last year’s Black List and comes from new screenwriter, Sean Harrigan.

Writer: Sean Harrigan

Details: 110 pages

Halle Bailey for Shae?

Halle Bailey for Shae?

I would say that if everyone in Hollywood were told that they could only market one genre and their paycheck would depend on those movies doing well, they’d choose Horror. Cause Horror is the most dependable genre in the business.

With that being said, there still seems to be an underlying ignorance to which of these films is going to do well and which will do poorly.

Big marketing campaigns were put together for Immaculate and The First Omen and both of them tanked.

Whereas this nothing little Australian horror film, Talk to Me, comes out of nowhere and becomes a mini-hit.

What gives?

The answer is more complicated than I’d like to admit. I know that the studios test all their horror movies ahead of time and if they get a certain score, they release them theatrically. In essence, they already know if the movie is going to play well. This is why Talk to Me got a wide release. Cause they saw how well audiences were responding to it.

But then you have stuff like The First Omen and Immaculate, which the studios had decided they were going to release wide even before they made them – one because of its rising star and the other because it was a franchise – despite the fact that their test screenings told them they were duds.

Whenever I get confused, I go back to basics. Come up with an original idea and then write a script that exploits that idea as much as possible. That’s why I loved The Ring. That’s why I loved The Others. That’s why I loved The Orphanage. That’s why I loved the original Scream.

Does “First You Hear Them?” achieve this? Let’s find out.

24 year old Shae Howland is so focused on dealing with her mother’s struggles with addiction that she hasn’t been able to begin her post-college career. In the meantime, the African-American aspiring nurse spends her nights with her Filipino roommate, Poppy, and gay Mexcian best friend, Javier (talk about a writer who knows what the Black List wants) spend their nights going out and having fun.

One night, while out at the club, the group tries a new drug – a sort of mangy brown pill. The clan has no idea where the drug came from or what it does but who cares! They’re young and invincible. It turns out it doesn’t do much. They get an average high, dance around, then everyone goes home.

But the next morning, Shae starts hearing a tapping noise, like someone nearby is tapping on a window – this, even when Shae’s nowhere near a window. The others confess to hearing the same thing but when they take another of the mangey pills, the sound goes away.

Soon, Shae’s ex-boyfriend Carson (cool name) comes into the mix. He seems to have a beat on this new drug and tells everyone that they have to keep taking the drug. “Or else what?” Or else they’ll not just hear them, they’ll see them. And if they don’t take the drug again, they won’t just see them, they’ll be hunted by them.

Carson tells the group that they need to secure more pills. Unfortunately, they’re expensive. So everyone’s going to need to get as much money as possible out of their bank accounts ASAP. Cause if they don’t get product soon, they’re going to move into the second phase (“Then you see them.”). From there, they’re only hours away from entering the third phase, which is when these things come after them. Once that happens, it’s game over.

In the upcoming weeks, I’m going to be placing a lot of focus ON DIALOGUE. I just wrote a book about it. It’s fresh in my mind. So I want to explore when writers excel at dialogue and when they falter.

If you’ve read my dialogue book, you know that I say, every single decision you make BEFORE you write your script is going to affect the dialogue. That includes genre. If you remember, I point out that Horror is one of the “non-dialogue-friendly” genres. It’s not known for birthing good dialogue.

So you already have an uphill battle ahead of you.

However, I also point out that if you’ve got a young cast, you can supercede this issue. People between the ages of 14-25 tend to have more colorful creative conversations. They’re using slang more often. They’re more playful with each other. And when you have younger characters, you’re looking to be more creative with the dialogue in general.

So I was disappointed with the lack of memorable dialogue here. It was all standard stuff. Not a single character had any unique identifiable phrases they used (something I talk about in the book). Every conversation was used strictly to push the scene forward and nothing more. Which is exactly what I told you not to do. You have to add some flair! You have to entertain, not just exposit.

Here’s an example on page 20.

Note that the only purpose of this dialogue is to get to the next scene. It has no beginning, no middle, no end. It is a scene fragment. Not a scene. It’s almost impossible to create good dialogue from scene fragments. The dialogue doesn’t have a chance to grow.

The only scene in the entire script where the dialogue is actually built to entertain is in the scene I’ll use for today’s “What I Learned.” But even that scene didn’t milk the dialogue for everything it could’ve been.

To be fair, as I said in the book, Horror is not built for dialogue. Every genre has the thing that it’s best at. Horror is best at scaring. So all that really matters is, does the script scare us?

It does. Just not enough.

The script leans almost too heavily into its premise in that the first rule (“First you hear them”) of the three doesn’t allow for a whole lot of scariness. We don’t even get our first “SEE THEM” moment until more than halfway into the screenplay. That’s a looooong time to wait to be scared.

That leaves the first 60 pages as basically “sound scares.” Are you scared by sounds? I suppose if I thought those sounds could turn into a killer monster, I might be. But here, I just felt that the sounds were annoying. It’s annoying that I want to brush my teeth but I have to hear tapping while I’m doing it. My preference is a non-tapping teeth-brushing evening.

Of course, once we get to the SEE THEM part, it gets scarier. And there is this naturalistic suspenseful arc to the game. Sort of like how, in The Ring, we knew that in 7 days, we were screwed. Here, we know that, after we hear them, after we see them, they come for us. So that suspense somewhat makes up for the inactivity.

I just wanted more to happen.

And it goes back to the dialogue. If your characters would’ve had more interesting conversations and weren’t muttering perfunctory things to get through the scenes, I would’ve been more entertained in the meantime. But if you’re giving me weak dialogue and no big scares for 60+ pages in a horror script, I’m going to complain.

I’m not saying this movie won’t be good. It’s got a great tagline (“First you hear them. Then you see them. Then they come for you.”). In fact, it would easily win Tagline Showdown this month. It even has a little depth to it. There’s a message here about how, when you become addicted to drugs, the high is your “normal.” So you have to keep doing drugs just to feel “normal.” If you stop, you descend into misery.

But I still gotta be entertained, man. And this script was only entertaining in spurts.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: In my dialogue book, I talk about the importance of situational writing. Situational writing is when you build your scene around a familiar situation that has rules, which, in turn, gives the scene structure. In one of the better scenes in the script, we see situational writing in practice. Our group, who is moving into the second phase of the rule (“Then you see them”), gets stopped by a couple of cops. Here’s how the scene plays out.

If today’s dialogue talk intrigued you, I have over (that’s right, OVER) 250 dialogue tips in my new book, “The Greatest Dialogue Book Ever Written.” You can head over to Amazon and buy the book, right now!

An excerpt from my upcoming book, “The Greatest Dialogue Book Ever Written”

There was a time when I didn’t think I was ever going to finish this book. There were too many technical obstacles (mainly regarding how ebooks interpret screenplay-formatted text) that required endless troubleshooting. But I’m SOOO excited that I’m finally about to release the book because I truly believe it will be the seminal book on dialogue for the next 50+ years.

It’s a book with 250 dialogue tips. This in an industry where you’re lucky to find someone who can give you 10 dialogue tips. And I just can’t contain how thrilled I am that I can finally share it with you. I already posted the opening of the book the other week. In today’s post, I’m including a segment from the “Conflict” chapter. This is arguably the most important chapter in the book and it contains 21 tips total.

TIP 121 – Make sure there’s conflict built into the relationship of the two characters who are around each other the most in your movie/show – Who are the two characters who will be around each other the most in your script? You need to build conflict into the DNA of that relationship specifically. That way, almost every scene in your movie is guaranteed to have conflict. John and Jane in Mr. and Mrs. Smith, Tony Stark and Steve Rogers in Civil War, Allie and Noah in The Notebook, Lee and Carter in Rush Hour, Danny and Amy in the Netflix show, “Beef.”

TIP 122 – Using worldviews to create conflict – Okay, but how do you build conflict into the DNA of a relationship? One way is to give characters different worldviews. Have them see the world differently. If you do this, your characters will be at odds with each other for an entire movie as opposed to one or two scenes. In the Avengers movies, Tony Stark’s worldview is he’s willing to get dirty to protect the universe. Steve Rogers’ worldview is governed by honesty. He wants to play by the rules. That difference in their worldviews is why the two butt heads so much.

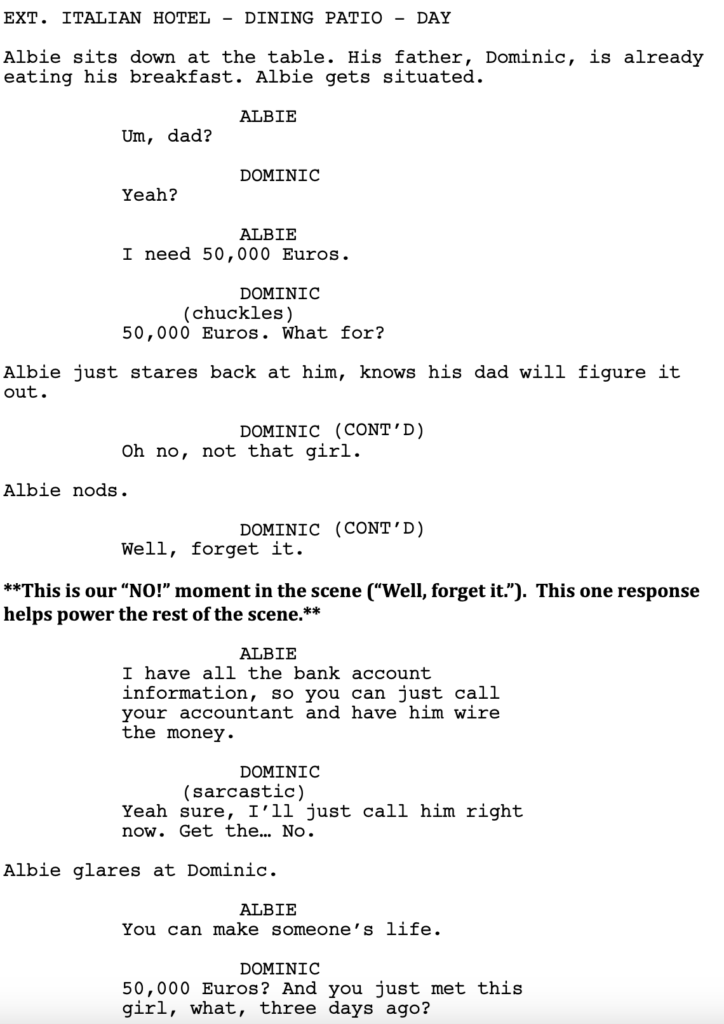

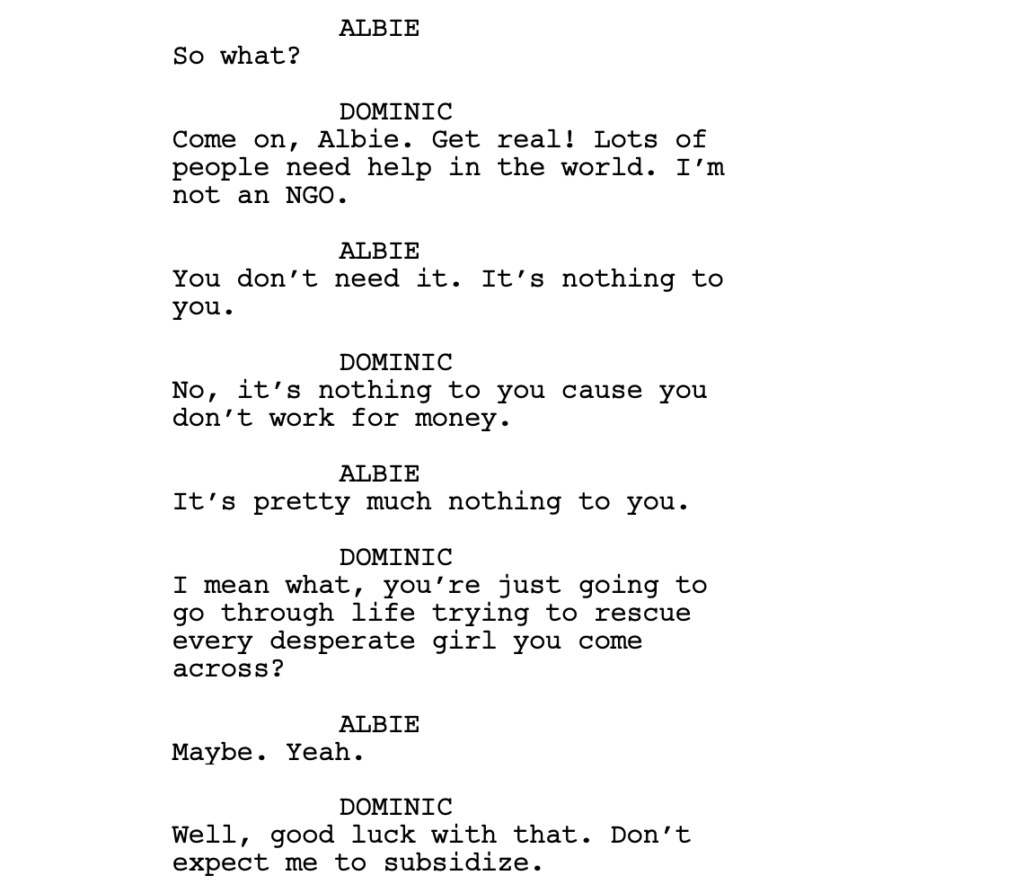

TIP 123 – Embrace the word “NO” – “No” is the OG conflict word. Without it, most conversations become boring. Let’s say your hero tells his wife, “I’m going to the store,” and she replies, “Okay.” How is that going to result in an interesting conversation? Or your assassin asks his handler, “Is it okay if I skip this assassination? I don’t think it’s safe enough.” And the handler replies, “Sure, no problem.” When people agree with people, the conversation immediately stops. This is why you want to integrate “No” (and all forms of it) into your dialogue. Here’s an example from the HBO show, White Lotus. In it, 23 year old Albie has fallen in love with a local Italian prostitute who owes her pimp money. Albie wants to help pay her pimp off, so he comes to his rich father to ask for money.

TIP 124 – Make them work for their meal – The reason “No” is so great for dialogue is that it forces your character to work for their meal. They don’t get a free pass. The above scene goes on for another three minutes and Albie has to resort to offering something to his father to get the money. That’s what makes the scene entertaining – that he has to work so hard for his meal. And he wouldn’t have had to do it if his dad had said, “Yes.”

The Scriptshadow Dialogue Book will be out within the next two weeks. But there’s a chance it could be out A LOT SOONER. So keep checking the site every day! In the meantime, I do feature script consultations, pilot script consultations, short story consultations, logline consultations. If you’ve written something, I can help you make it better, whether your issues involve dialogue or anything else. Mention this post and I will give you 100 dollars off a feature or pilot set of notes! Carsonreeves1@gmail.com

An excerpt from my upcoming book, “Scriptshadow’s 250 Dialogue Tips”

It has been promised. But as of yet, it hasn’t been delivered.

Over the next month, I’ll be including excerpts from my upcoming dialogue book, which I’m planning on releasing a month from now. Here is the introduction to the book. The world of screenwriting is about to change forever.

What you’re about to read is the introduction to the book…

Not long after I started my website, Scriptshadow, a site dedicated to analyzing amateur and professional screenplays, I was hired by an amateur writer to consult on a script he had written. The writer had completed a couple of screenplays already and was excited about his most recent effort, a crime-drama (“with a hint of comedy”) he felt was the perfect showcase for his evolving skills. Although I won’t reveal the actual script for privacy reasons, we’ll refer to this screenplay as, “Highs and Lows,” and we’ll call the writer, “Gabe.”

Highs and Lows was about a guy obsessed with a rare street drug and, to this day, it is one of the worst screenplays I have ever read in my life. We’re talking 147 pages of unintelligible nonsense, a script so aggressively lousy, I considered submitting it to the CIA as a low-budget alternative to waterboarding.

After I put together the notes on Highs and Lows, I spent a good portion of the day debating whether I should call Gabe and aggressively suggest he pursue a different career path. I’d never done such a thing before. But, in my heart, I knew that if this man pursued this craft, he may very well end up wasting a decade of his life. If it wasn’t for my girlfriend ripping the phone out of my hand and telling me there was no way I was going to destroy this writer’s dreams, I would’ve made the call. Instead, I sent him his notes, detailing, as best I could, what needed to be improved and how to do so, and moved on.

Cut to five years later and I was contacted by a different gentleman (we’ll call him “Randy”) for another consultation. In stark contrast to Gabe’s script, I experienced what every reader prays for when they open a screenplay, which is a great easy-to-read story with awesome characters. But it was the dialogue that stood out. Randy wasn’t ready to challenge Tarantino just yet but the conversations between his characters were always clever, always engaging, and always fun.

I sent his script out to a few producers and one of them ended up hiring him for a job. He wrote back, thanked me, and mused that he’d come a long way since our first consultation. “First consultation?” I said to myself. “What is this guy talking about?” I looked back through my e-mails to see if we had corresponded before and nothing came up. But then I dug deeper and discovered that I *had* worked with Randy before. Under a different e-mail address.

The owner of that e-mail?

Gabe. Which was a pen name he had used at the time.

This was not possible. Randy wrote with confidence. Gabe wrote like he’d accidentally fallen asleep on his keyboard. I went back and re-checked, checked again, checked some more, only to return to the same baffling conclusion. This page-turning Tour de Force was written by the same writer who had written one of the worst screenplays I’d ever read!

After my denial wore off, I got in touch with Gabe and asked him the question that had been eating at me ever since I confirmed his identity: “What in the world did you do differently this time around?” I especially wanted to know how his dialogue had skyrocketed from a 1 out of 10 to an 8 out of 10. His answer is something I’ll share with you later in the book, as it’s one of the most important tips you’ll ever learn about dialogue.

But for now, I want to emphasize the lesson Gabe’s dramatic improvement taught me, something I remind myself whenever I read a not-so-good screenplay: You are always capable of improving as a screenwriter. If Gabe could go from worst to first, so can you.

Which is why I want to share with you one of the biggest lies you’ll encounter when you begin your screenwriting journey. I heard it a bunch when I first started screenwriting and I still hear it today: “You either have an ear for dialogue or you don’t.” This faulty statement, which you’ll hear mostly from snobby agents, jaded executives, and impatient producers, is dead wrong.

Writing good dialogue can be learned.

Let me repeat that:

Writing good dialogue can be learned.

To be fair, doing so is challenging. More so than any other aspect of the craft. Aaron Sorkin, who many believe to be the best dialogue writer working today, admits as much. In an interview with Jeff Goldsmith promoting his film, The Social Network, Sorkin confessed that while storytelling and plotting are built on a technical foundation, making them easy to teach, writing dialogue is more of an instinctual thing, and therefore hard to break down into teachable steps.

Indeed, dialogue contains elements of spontaneity, cleverness, charm, gravitas, intelligence, purpose, playfulness, personality, and, of course, a sense of humor. This varied concoction of ingredients does not come in the form of an official recipe, leaving writers unable to identify how much of each is required to write “the perfect dialogue.” Which has led many screenwriting teachers to throw up their hands in surrender and label dialogue, “unteachable,” which is why there hasn’t been a single good dialogue book ever written.

When screenwriting teachers do broach the topic of dialogue, they teach the version of it that’s easiest on them, which amounts to telling you all the things you’re NOT supposed to do. My favorite of these is: “Show don’t tell.” Show us that Joey is a ladies’ man. Don’t have him tell us that he’s a ladies’ man.

“Show don’t tell” is actually good screenwriting advice but why do you think screenwriting teachers are so eager to teach it? Because it means they don’t have to teach dialogue! If you’re showing something, you’re not writing any conversations.

Or they’ll say, “Avoid on-the-nose dialogue.” Again, not bad advice. But how does that help you write the dialogue that stumbles out of the mouth of Jack Sparrow? Or sashays out of the mouth of Mia Wallace? In order to write good dialogue, you need to teach people what *to* do, not what *not to* do.

If you ever want to test whether a self-professed screenwriting teacher understands dialogue, ask them what their best dialogue tip is. If they say, “go to a coffee shop and listen to how people talk,” run as far away from that teacher as possible because I can promise you they know nothing about dialogue. If someone is giving you a tip where there’s nothing within the tip itself that teaches you anything, they’re a charlatan.

What the heck is good dialogue anyway?

Good dialogue is conversation that moves the scene, and by association the plot, forward in an entertaining fashion. “Entertaining” can be defined in a number of ways. It could mean the dialogue is humorous, clever, tension-filled, suspenseful, thought-provoking, dramatic, or a number of other things. But it does need those two primary ingredients.

• It needs to push the scene forward in a purposeful way.

• It needs to entertain.

What prevents writers from writing good dialogue? That answer could be a book unto itself but in my experience, having read over 10,000 screenplays, the primary mistake I’ve found that writers make is they think too logically.

When they have characters speak to one another, they construct those characters’ responses in a way that keeps the train moving and nothing more. They get that first part right – the “move the story forward” part – but they forget about the “entertain” part. Don’t worry, I’ve got over a hundred tips in this book that will help you write more entertaining dialogue.

Yet another aspect missing from a lot of the dialogue I read is naturalism – the ability to capture what people really sound like when they speak to each other. You are trying to capture things like awkwardness, tangents, authenticity, words not coming out quite right. You’re trying to mimic all that to such a degree that the characters sound like living breathing people.

And yet, while being true-to-life, you’re also attempting to heighten your dialogue. You’re trying to make every reply clever. You’re trying to nail that zinger. You’re giving your hero the perfect line at the perfect moment. How does one combine realism with “heightened-ism?” That’s one of the many paradoxes of dialogue.

So I understand, intellectually, why so many teachers are terrified of dialogue. The act of writing movie conversation is so intricate and nuanced that the easy thing to do is leave it up to chance and tell writers that they either have an ear for it or they don’t (or to go to a local coffee shop and “listen to people talk”).

But dialogue is like any skill. It can be learned. It can be improved. And I dedicated years of my life looking through millions of lines of dialogue, ranging from the worst to the best, to find that code. And I believe I’ve found it. By the end of this book, you’ll have found it as well.

It won’t be easy. This is stuff you’ll have to practice to get good at. But, once you do, your dialogue will be better than any aspiring writer who hasn’t read this book. That much I can promise you.

So let’s not waste any more time. I’m going to give you 250 dialogue tips and I’m going to start with the two biggest of those tips right off the bat. If all you ever do for your screenwriting is incorporate these two tips, your dialogue will be, at the very least, solid. Are you ready? Here we go.

TIP 1 – Create dialogue-friendly characters – Dialogue-friendly characters are characters who generally talk a lot. They are naturally funny or tend to say interesting things, are quirky or strange or offbeat or manic or see the world differently than the average human being. The Joker in The Dark Knight is a dialogue-friendly character. Saul Goodman in Breaking Bad is a dialogue-friendly character. Deadpool is. Juno is. It’s hard to write good dialogue without characters who like to talk.

TIP 2 – Create dialogue-rich scenarios – Dialogue is like a plant. It needs sunshine to grow. If every one of your scenes is kept in the shade, good luck sprouting great dialogue. A scene where a young woman introduces her boyfriend to her accepting parents is never going to yield good dialogue. There’s zero conflict and, therefore, little chance for an interesting conversation. A scene where a young woman introduces her boyfriend to her highly judgmental parents who think their daughter is too good for him? Now you’ve got a dialogue-rich scenario!

I need you to internalize the above two tips because they will be responsible for the bulk of your dialogue success. Try to have at least one dialogue-friendly character in a key role (two or three is even better). Then, whenever you write a scene, ask yourself if you’re creating a scene where good dialogue can grow.

Don’t worry if these two things are confusing right now. We’re going to get into a lot more detail about how to find these dialogue-friendly characters and how to create these dialogue-rich scenarios.

A pattern you’ll notice throughout this book is that good dialogue comes from good preparation. The decisions you make before you write your dialogue are often going to be just as influential as the ones you make while writing your dialogue.

There’s more to come next week! If you want to hire me to take a look at your script and help you with your dialogue (or anything else), I will give you $100 off a set of feature or pilot notes. Just mention this post. You can e-mail me at carsonreeves1@gmail.com

The short story sale only took 45 years to happen

Genre: Dystopian/Sci-Fi Adjacent

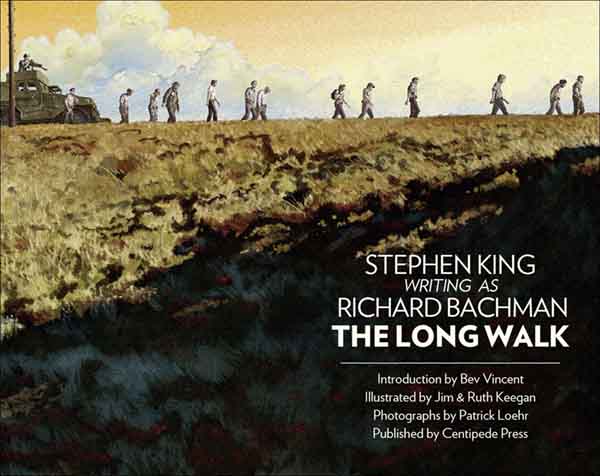

Premise: 100 teen boys participate in an annual event that forces them to do a death walk until there is only one left.

About: Okay, I’m cheating a little. This isn’t technically a short story. But it’s a short story in Stephen King Language, as the man is known for writing 700 page novels. Technically, he would call this a novella. King also wrote this under his fake author doppelgänger, which King invented once he became too popular and figured everyone was buying his books regardless of whether they were good or not. He wanted to challenge himself and see if he still had it as an author, which is why he invented Bachman. The Long Walk, which is 45 years old at this point, was purchased by Lionsgate and will have Hunger Games director Francis Lawrence direct. The film was almost made twice before, once by George A. Romero and once by Frank Darabont.

Writer: Richard Bachman (Stephen King)

Details: (1979) A little under 250 pages, hardcover.

I’ve decided that I’m going to do a Short Story Showdown at some point this year. I’m not sure when but it will probably be June or July. So start coming up with that short story concept because we can’t deny what the current trend is, which is short stories, short stories, short stories.

If I could give you one piece of short story advice, come up with a big idea. Think “high concept” even more so than you would a script. Cause a lot of these short stories are a quarter the size of a screenplay. So you don’t really have time to put your characters through some complex arc. It’s more about a sexy idea that’s going to generate interest in potential moviegoers.

The Long Walk is a great example of this. It’s all about the idea. Let’s see if it offers us anything else.

16 year-old Ray Garraty was chosen to be one of the contestants for The Long Walk, a yearly competition where thousands of boys enter their names in a hat for a chance to compete for the grand prize – all the money you need for the rest of your life. Only 100 names are chosen and Ray is one.

No sooner do we meet Ray than the walk begins! The rules are simple. You have to keep up a pace of 4 miles per hour. If you don’t, you get a warning. You get three warnings total. The fourth time, they shoot you. As in, THEY KILL YOU. The last remaining person to be walking is the winner.

Ray immediately teams up with a guy named Peter McVries. Whereas Ray is more of a wholesome chap, Peter’s got an edge to him. It feels like he’s hiding a few secrets inside that noggin of his. But Peter seems to be as supportive of Ray as he is himself. The two lean on each other a lot as the first contestants “buy their ticket” (Long Walk code for “shot dead”).

The story doesn’t deviate much. It leans into the long grueling competition of trying to keep walking when you’re tired, when you get a Charlie horse, when you get a cramp, when you’re bored, when you get blisters on top of your blisters, when your shoes come apart, when your body wants to give in. Many a contestant tries to game the system – run into the crowd to escape, thinking the guards won’t possibly shoot at them. But it never works. The crowd wants to see them die so they push them back to allow the guards a clear shot.

15 miles turns into 20. 20 to 50. 50 to 100. Days go by. 5 of them in all. Somehow, some way, Ray keeps going. At a certain point, it’s just Peter and Ray. (Spoiler) But then Peter can’t go on. He’s too exhausted. Which means Ray is going to win. When Peter is shot, that’s exactly what we think. It’s over. But did Peter lose count? Is there another player he must outlast? Or is that player death himself? Is Peter even in the game anymore?

A few of you are probably asking, “Why’d you pick this to read, Carson?” Here’s why. The Hollywood system is so obsessed with the word “no,” due to the fact that it keeps them from having to make a decision, that when they finally say “Yes” to something, it’s a really big deal. It’s so hard for any executive to say yes because they know, once they do, that project could go horribly bad and, if it does, they’ll be fired. It’s probably the best view into an exec’s mind you’re going to get. Committing to anything is so daunting that there HAS TO BE SOMETHING SPECIAL about that project for them to say yes to it.

But if I’m being honest with you, the real reason I chose to read this as opposed to a script that sold or a script that made the Black List, is that I knew it was going to be entertaining. King has his storytelling faults. But his stories always place “entertaining the reader” first. So I know I’m going to enjoy the experience of reading The Long Walk.

I’ve read too many scripts to know that most writers don’t prioritize entertainment when writing a story. They’re writing for their own egotistical reasons. Or they’re trying to write something that’s taken seriously. Or they think that readers will stay with them for thirty pages of setup to get to the good stuff.

All King thinks about is the reader. That’s why he’s the most well-known living author. If every writer could take in just a quarter of that desire that King has to entertain people, their scripts and stories would be so much better.

And that’s exactly what happened. I was entertained from the jump.

I mean, do you know how quickly we get to the walk here? Within the first ONE PERCENT of the story! That’s how determined King is to entertain. He knows why you bought this book and he’s going to deliver on that promise. This is especially important with short stories. Not only do you need a high concept premise. But you need to get into that premise faster than when you’re writing a script.

What’s interesting here is that the entertainment comes at us in an unorthodox way. I’m not surprised at all that George Romero was once attached to this because the deaths here aren’t fast and furious. They work more like zombie deaths, where they come slowly. The people involved realize minutes, sometimes hours, ahead of time, that their death is coming. This makes the deaths more realistic, intense, and emotional.

When one kid tells Ray that he’s got a cramp and he’s looking to Ray for help, Ray looks back at him like, “I can’t do anything for you.” And the realization this kid has that nobody can help him is devastating.

That’s the majority of the book. King introduces us to kids along the way, tells us just enough about them to get us to care, then kills them off later on.

Another thing I liked about this story was the rules.

As with any sci-fi (or sci-fi adjacent) story, you have to have rules. Where so many writers screw up is they make their rules too complicated. Or they have too many of them. Or both. Note how simple the rules are here. You have to keep up a 4mph pace. You get three warnings. On the fourth, they shoot you. That’s it! For some reason, writers think that they’re not getting enough out of their story if the rules are simple. So they invent all these complicated rules. But the opposite is true. When the reader easily understands the rules, all they have to do is enjoy the story. They don’t have to constantly rack their brain to remember a + z = q.

Another great lesson you can take from this story is how impossible King makes it feel. With every script you write, you need to make the goal as impossible-feeling as you can AS EARLY as you can.

Ray is not dead tired on mile 97 when there are 3 kids left. He’s dead tired on mile 20 with 97 kids left. That’s how to make the reader wonder, “How in the world is he going to last?” And if the reader is asking that question, I guarantee they’ll keep turning the pages. It’s only when there are no questions left to answer, or the answers to the questions are obvious, that the reader stops reading.

The story does have narrative limitations. It starts to get monotonous since there’s only one thing to do. And I thought that King could’ve done more with the Ray and Peter friendship. If he could’ve made us love this friendship, like he did the kids in Stand By Me, their final walk together would’ve been a lot more emotional. And then, the ending needs work. You could tell King didn’t know how to end this. Luckily, there are options here, starting with strengthening that friendship.

Overall, a solid story that should be a good, but not great, movie.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[xx] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: A sound strategy for screenwriting is to see what the hot new trend is and go back through your finished scripts to see if you have anything similar. You can do this starting from scratch (writing a brand new script) as well. But trends are finicky. They can last a year. They can last five years. So any sort of head start is preferable. There’s no doubt in my mind that this story got purchased due to the success of Squid Game. And, to be fair, it’s been a while since that show came out. Regardless of that, the quicker you can move on a trend, the better. So if you have that old abandoned spec that is similar to the hot new thing, dust it off, give it a quick rewrite, and get it out there!

One of the biggest short story sales of 2023!

Genre: Thriller

Premise: An American negotiator in London is called in to help deal with a unique situation – a construction worker is stuck on top of an old World War 2 bomb, which could detonate in response to the slightest movement.

About: This is the big flashy short story sale that happened recently, which landed Ridley Freaking Scott as director. Ridley Scott, who’s making Gladiator movies, for goodness sake, is not easy to lock down into a director role, especially at 85, when he only has so many bites at the apple left. So to say my anticipation levels for this one are soaring would be an understatement.

Writer: Kevin McMullin

Details: 5250 words. I know this because the writer tells us that on the first page. Will this now become the standard for short stories? (An average script is 22,000 words)

I have one question for you. Are you on the short story train yet?

Cause the train is moving people. It’s zipping and zapping its way around Hollywood – down through Culver City into the Sony Lot, up Highland before stopping at Paramount, over to Pico to give all the Fox Studio execs high fives, before muscling up the 101 into the Valley to visit all the valley girl studios.

Someone asked me the other day, “Is the spec script dead?” I said, “No! It’s just morphed into the spec short story.” And here’s the trick that writers are starting to get wise to – when you send your short story out there, you sell it with the stipulation that you get to write the first draft. Which means – if you’re paying attention – you ARE selling a spec script. You’re actually selling it before it’s written. Which means you’re a screenwriting time machine. That’s so much cooler than being a boring spec script writer.

Fear not, script purists. The short story craze does not mean you should drop all your screenwriting aspirations. The industry still needs screenwriters. They can’t live without them. So you should still be writing scripts that wow people so that you can get hired to write all those other projects Hollywood wants to make.

Today, however, we’re doing another short story dance. So throw on your dance shoes and join me. I’ll lead.

American Francis Ipolito, a negotiator, is getting married in the UK over the weekend. He’s staying alone in his hotel room the night before the wedding. That is until his best friend and best man, FBI officer Dwight, calls him and tells him to check the news. Francis does and sees that Piccadilly Circus (London’s Times Square) is cleared out.

In a dug-up construction area, a construction worker is standing on top of an old World War 2 bomb. These bombs are known to be delicate. Even the slightest move could detonate them. So the man is frozen. Less than ten minutes later, a UK government official shows up at Francis’s hotel and says to come with him. Francis says, “Only if my buddy Dwight can join me.”

Once at the bomb site, Ministry of Defense Aoife Greggor tells Dwight to beat it and informs Francis that the whole World War 2 bomb thing was a lie. They put that out there for the press. The real deal is that the construction worker BUILT THIS GIANT BOMB he’s standing on top of and has demanded to talk with Francis.

Francis heads over to the Piccadilly construction site, with no idea of who this dude is, only to learn that he’s his fiancé’s ex-husband! Francis is called back to base, where he’s then informed that his buddy, Dwight, was given clearance to join a UK reconnaissance team charged with clearing the surrounding buildings.

Their first building they’re clearing is actually the one Dwight happened to be staying in via Air BnB. Francis freaks out, tells them to get the team out of there as soon as possible. But it’s too late. We hear a big BOOOOM. Dwight is now dead from a second bomb that the bomber planted earlier. Francis turns to Aoife: ‘How many bombs are there?’ The End.

I kid you not. That’s the end of the story.

I sensed something was off with this one right away.

The writing was clunkier than a ride in a square-wheeled wagon. I was constantly having to go back and re-read things to properly understand them. Even then, I didn’t always get what had been written.

This caused me to lose confidence in the writer as the story went on. For that reason, I knew it wasn’t going to deliver. But what I didn’t know was how spectacularly it would fail to deliver. I mean this isn’t just a bad short story. This is bad everything.

I don’t want to be mean because it isn’t the writer’s fault that his story sold and nabbed one of the best directors in the business. But with that success, readers are going to go into this with high expectations. And man, let me tell, this is not the kind of story you want people reading with high expectations. You want them going in with subterranean expectations. Even then, though, they’ll be disappointed.

Let me give you an example of how bad the writing is. It’s late in the story. There are a few pages left. Francis has just come back from talking to the bomber dude and asks Aoife where Dwight is.

Aofie, who mind you hated Dwight and was trying to get rid of him since the second he showed up, informs Francis that Dwight has joined the British reconnaissance team. Even if we stopped there, that’s terrible writing. There’s no way any British service is going to have some random off-duty American FBI guy join their team on the spot. Also, you’ve set up that the Ministry of Defense hated this guy. So why would she allow him to join one of her teams?? In less than five minutes no less!!????

But it gets worse!

Aofie tells Francis that the team is investigating a building nearby, a building that just so happens to ALSO be the AirBnb apartment Dwight is staying at. In that moment, Francis realizes that this was all part of the bomber’s plan. So he tells Aofie to get the men out of that building as quickly as possible. But before they can act, the building blows up from a DIFFERENT BOMB the bomber planted earlier, and Dwight is dead.

Think about that for a second. The number of hoops we need to jump through for this to make sense is astounding.

In order for the bomber’s plan to work, he would’ve had to secretly set up a bomb weeks ago below Dwight’s AirBnB building AND THEN, since Dwight wasn’t actually at the building, the writer needed to construct a scenario by which the British bomb team recruited Dwight on the spot, and then, of the hundreds of surrounding buildings they could’ve gone to, the writer made the team coincidentally go to Dwight’s AirBnB building, so that the bomber could kill him.

All of this was done via a payoff THAT WAS NEVER SET UP. Because we didn’t even know about any other bombs until the second one blew up. So none of it feels earned or realistic. It’s the kind of sloppy writing that even low-level Hollywood execs don’t let fly.

Everywhere you look in this story, it’s bad. There are no positive attributes at all other than it’s sort-of high concept. It was one of those situations where I actually thought I got duped – that someone sent me the wrong “Bomb” story. That’s how ugly it got.

This begs the question. If this story is so bad, why was it purchased? One of the frustrating things I’ve learned about Hollywood is that every working individual has their specific movies that THEY WANT TO MAKE. Only that person and their close friends know what those movies are. We, outside the business, don’t know what they are. So we can’t write the script that Denzel Washington is desperate to make or pitch the movie Jacob Elordi has wanted to be in since he was five.

I suspect that Ridley Scott really wanted to make a negotiator movie or a bomb movie and this came across his desk. Boom. That’s it. He was in because this is the exact type of movie he wants to make right now. And make no mistake, after he lets McMullin write his contract-guaranteed first draft, he will bring in a much more established screenwriter to write a version of this that actually makes sense. Cause if he goes with this version, it will be one of his worst movies ever.

Of all the short story sales I’ve seen so far, this is by far the worst.

[x] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned 2: Is getting married a short story sale hack? This is the second big sale in a row (the last was Run For Your Life) where an impending wedding was the centerpiece. Weddings give you ticking time bombs and heightened emotions, both of which create more drama. Not saying you SHOULD use a wedding. But there’s clearly something to it.