Search Results for: F word

The Karate Kid makes 56 million on its opening weekend. I don’t think anyone saw that coming. Not even “I’ve never failed at anything in my entire life” Will Smith! This is great news for Jackie Chan as well, who was just about to commit to a The Spy Next Door sequel, which we all know would’ve been titled, “The Spy Next Door Too.” I did not see Karate Kid, but I have to admit, the trailers did not look awful. The actors seemed to be taking the movie seriously, and against all odds, it kinda worked. Have no idea if the full movie is the same. Here at Scriptshadow, I’m reviewing an Oscar winning screenwriter tomorrow, putting together what should be a fun little article for Wednesday, and am yet to commit to my Thursday and Friday reviews. Today, Roger comes at you with a script I’m 97% certain was written specifically for him. Here’s “The Book Of Magic.”

Genre: Fantasy Adventure, Horror

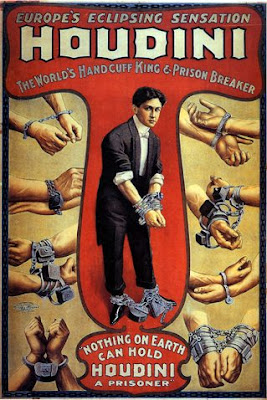

Premise: Harry Houdini teams up with the legendary author, H.P. Lovecraft, to track down a supernatural serial killer in 1920s New York City.

About: This script won first prize in the 2003 ManiaFest Screenplay Competition and landed Sheldon Woodbury a writing assignment for Jeff Sagansky, a producer who used to be the president of Sony Pictures.

Writer: Sheldon Woodbury

Surely, as deep calls to deep, mystery attracts mystery. Which is an idea explored in “The Book of Magic” (not to be confused with Neil Gaiman’s The Books of Magic), a tale where the infamous escape artist Harry Houdini teams up with the grandfather of horror fiction to catch a supernatural serial killer in 1920s New York City. That logline appeared in my inbox a few weeks ago and all I could do was stare at it and exclaim, “Seriously?” As a reader of this blog, it doesn’t take a lot of homework to know that I love two things:

[ ] wasn’t for me

[xx] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

Genre: Comedy

Premise: A man is forced to travel cross-country with his annoying brother in order to get to his wedding.

About: Disney picked this spec up back in 2009 for 250k. Kopelow and Seifert have been writing for TV for over a decade, having worked on shows ranging from “Kenan & Kel” to Oxygen’s “Campus Ladies.”

Writers: Kevin Kopelow and Heath Seifert

Details: 98 pages – May 16, 2008 (This is an early draft of the script. The situations, characters, and plot may change significantly by the time of the film’s release. This is not a definitive statement about the project, but rather an analysis of this unique draft as it pertains to the craft of screenwriting).

The best “two guys stuck together traveling cross-country” movie is Dumb and Dumber by a mile. The script was actually a bit of a gamble when you think about it. Whenever you write about two people stuck together in any situation, the traditional approach is to make one guy the “crazy/dumb/weird” guy and the other guy the “straight man.” The extreme contrast between the two characters usually provides the most potential for comedy. The Farrelly brothers said screw that and just put two idiots together. Somehow, we got a classic.

The Most Annoying Man In The World goes back to the more traditional pairing of super extreme guy and super straight guy, and proves that it’s still a safe bet when done well. Stuart Pivnick IS the most annoying man in the world, and I have to give it to Kopelow and Seifert for giving us one of the best descriptions I’ve ever read in a comedy. Stuart is described as… “an enthusiastic, hyper, immature, naive, nosy, arbitrarily opinionated, completely un-self-aware, chronic complainer with no sense of personal space.” I love how they not only have fun with the description, but how it perfectly portrays Stuart in the process.

Across the country, finishing his bachelor party in Las Vegas, is Stuart’s brother, Alan. Alan is basically the opposite of everything Stuart is. He always wants to get everything right and boy has that become a problem with his wedding fast approaching. Everything seems to be going wrong and Alan is having to do damage control minute by minute from 2000 miles away.

Alan also hasn’t spoken to his brother in over a decade. Why? Well because he’s the most annoying man in the world! In fact, so relentlessly annoying is Stuart, that Alan’s created a ruse whereby he works at a remote research facility in the middle of the South Pole, one where he’s supposedly unable to communicate with anyone outside of his research operators.

But when Alan gets stuck at O’Hare and all of the day’s flights are canceled, he’s forced to call the only person he knows in town. Stuart.

Stuart, of course, is thrilled! He loves Alan more than anything. And when’s the next time the government is going to let his poor brother out of that research facility? So he welcomes Alan in with open arms, situating a second mattress inside his bedroom so they can both sleep together, then proceeds to read out loud and sing in his sleep all night so that Alan doesn’t get a wink of rest.

Despite being late the next morning, Stuart drives the exact speed limit to the airport, and this leads to a series of problems which result in Alan missing his flight. But Stuart comes up with the wonderful idea that they just drive to Philly together! With options dwindling, Alan agrees. Because Alan can’t tell Stuart *why* he needs to get to Philly so urgently (there’s no way he’s allowing Stuart to come to his wedding), it results in a logistical nightmare, as more and more wedding plans continue to fall apart, and Alan must manage them without letting Stuart on to what he’s up to.

The two take many detours, with Stuart repeatedly screwing everything up as much as humanly possible. He has a medical condition that forces him to eat at EXACT times, flipping out if he’s even a second late. He listens to movie scores in the car and makes up his own words to them (He’ll listen to E.T. and sing “E.T. likes reeses pieeeeces. He’s going home soooon.”) He likes to play games like “Guess a number between one and a million” where Alan picks a number and Stuart keeps guessing which number it is til he’s right. He truly is the most annoying man in the world. And for the most part, it’s really funny.

But like I always tell people who write comedies, you have to have the story and the emotional element up to the level of the comedy, and Kopelow and Seifert do a great job with that here. This is just as much about getting to Philadelphia without letting Stuart in on his wedding as it is about funny scenes. It’s just as much about two brothers reconnecting as it is about making an audience laugh.

I saw “Get Him To The Greek” this weekend and what baffled me was just how unimportant the story was. Nobody really gave a shit about GETTING TO THE DAMN GREEK! Outside of Jonah Hill half-heartedly reminding Aldous every few scenes, nobody, from the record label to the fans, gave a shit whether Aldous made it to his concert or not. I remember that at least in the original script, Aldous hadn’t played a concert in 10 years. So it felt like the concert actually meant something and was a special event. Here, he plays a fucking concert in the middle of the damn movie!!!, completely sucking dry any of the importance of the concert that’s supposed to be the whole damn point of the movie! – My point is, if we don’t feel the push of the story – If that isn’t completely dominating the narrative – then none of the comedy freaking matters. The Most Annoying Man In The World, much like The Hangover, feels like the characters’ plight actually matters and isn’t just a convenient destination for the movie to end.

My only real complaint here is that the script needs to axe some of the generic situations its characters find themselves in. At first, going to a carnival/theme park sounds funny, but in the end it has very little to do with their specific journey, and therefore feels more like a desperate laugh grab than a logical story sequence. In fact, I think all of the set piece scenes here could use a jolt, except for the car getting stuck on an ice sheet scene – which had me laughing for a good five minutes. I thought The Hangover did this well. In the initial draft of that script, one of the guys wakes up to find out he was at a gay bar the previous night. I couldn’t figure out why they ditched that in the film, but then I realized we’ve seen that before. We’ve never seen characters steal Mike Tyson’s tiger though. It just reminded me how you have to push yourself to come up with original sequences in comedies.

Overall, a solid comedy. And more importantly, one I think could make a great movie.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Comedies, more than any other genre, allow you to tell your story in the title. 40 Year old Virgin. Knocked Up. This is obviously a huge advantage in an ADD Twitter-obsessed 5-second-version no-fat-allowed world. But don’t just sum up your movie in the title, make sure it’s still funny and/or jumpstarts the imagination for what kind of movie it could be. 40 Year Old Virgin did the best job of this (I immediately thought of all the hilarious scenes you could have of a 40 year old man trying to get laid for the first time) and the 2008 spec sale “I Wanna F— Your Sister” also did a wonderful job. But that doesn’t mean it’s easy. There’s still an art to it. “Two Guys, One Who’s Dumb, Roadtrip To Marriage,” may tell us your story, but doesn’t roll off the tongue. So if the opportunity’s there and you come up with something clever, do it. If not, specs like “Due Date” and “Cedar Rapids” are still selling. So don’t sweat it.

Everybody always says it. The one surefire way to break into the industry is to write a great script. “All you have to do is write a great script,” they say. “Ohhhh,” you reply, “That’s it? “That’s all I had to do all this time?? Was write a great script? Well why didn’t you say so? And here I was working on my 20th really bad script!” Bitter reactions aside, it’s true. Write a great script and you’re in.

What hasn’t been clarified is what “great” means. Well I got to thinking (yes, it does happen). Why don’t I post exactly what a “great script” is so there’s no more confusion? Now when we say, “Just write a great script,” people will actually have something to reference. This idea sounded brilliant when I first came up with it, but the more it marinated, the more I realized that if writing a great script could be explained in a 2500 word blog post, we’d probably all be millionaires.

However, that doesn’t mean I can’t offer a list of 13 things I consistently see in great scripts. It may not be a step by step guide but at least it’s something. Yeah, I thought. That might work.

Now while I was hoping to provide an all-inclusive list of tips to best help you write a great script, the reality is I’ve probably forgotten a couple of things. So this is what I’m going to do. In the comments section, I want you to include what YOU think makes a great script. Over the course of today and tomorrow, I’ll update this post to include the best suggestions from you guys. Together, we’ll create *the* perfect go-to list when it comes to writing a great script. Isn’t this wonderful? Team Scriptshadow!

So here they are, in no particular order…

1) AN ORIGINAL AND EXCITING CONCEPT

This is the single most important choice you will make in writing your script because it will determine whether people actually read it or not. I used to hear agents say, “90% of the scripts out there fail before I’ve even opened them.” And it’s true. If you don’t have a compelling concept, nothing else matters. This slightly circumvents the “great” argument because nobody’s saying you can’t write a “great” script about a boy who goes home to take care of his ailing mother. But the reality is, nobody’s going to get excited about reading that script. Even the kind of people who WOULD want to read that script probably won’t because they know it’s a financial pitfall. It’ll take 5 years off their life and, in the end, play in 10 theaters and make 14,286 dollars. Now obviously an “exciting” idea is objective. But it’s fairly easy to figure out if you have something special. Pitch your idea to your 10 best friends. Regardless of what they *tell* you, read their reactions. Do their eyes and voices tell you they’re into it? If you get 10 polite smiles accompanied with a “Yeah, I like it,” it’s time to move on to the next idea. So give me your Hangovers. Give me your Sixth Senses. Shit, give me your Beavers. But don’t give me three people in a room discussing how their lives suck for 2 hours. And if you do, make it French. –

2) A MAIN CHARACTER WHO WANTS SOMETHING (AKA A “GOAL”)

Some people call it an “active protagonist.” I just call it a character who wants something. Ripley and the marines want to go in and wipe out the aliens in “Aliens.” Liam Neeson wants to find his daughter in “Taken.” The girl in “Paranormal Activity” wants to find out what’s haunting her house. The stronger your character wants to achieve his/her goal, the more compelling they’re going to be. Now I’ll be the first to admit that passive characters sometimes work. Neo is somewhat passive in The Matrix until the end. And, of course, Dustin Hoffman is the most famous passive character of all time in The Graduate. But these characters are tricky to write and require a skill set that takes years to master. In the end, they’re too dangerous to mess around with. Stick with a character who wants something.

3) A MAIN CHARACTER WE WANT TO ROOT FOR

This is one of the more hotly debated topics in screenwriting because a character we “root for” is usually defined as being “likable,” and there are a whole lot of screenwriters out there who would rather bake their craniums in a pizza oven than, gasp, make their protagonist “likable.” I got good news. Your hero doesn’t have to be “likeable” for your script to work. But you DO have to give us a character we want to root for, someone we’re eager to see succeed. He *can* be likable, such as Steve Carrel’s character in “40 Year Old Virgin.” He can be defiant, like Paul Newman in “Cool Hand Luke.” But he has to have some quality in him that makes us want to root for him. If your character is mopey, whiney, and an asshole, chances are we’re not going to want to root for that guy.

4) GET TO YOUR STORY QUICKLY!

Oh man. Oh man oh man oh man. As far as amateur screenplay mistakes go, this is easily one of the Top 3. Even after I explain, in detail, what the mistake is, writers continue to do it. So I’m going to try and make this clear. Are you ready? “Your story is moving a lot slower than you, the writer, believe it is.” For that reason, speed it the fuck up! In other words, that ten page sequence which contains 3 separate scenes, each pointing out in its own unique way that your hero is irresponsible? Well we figured it out after the first scene. You don’t need to waste 7 more pages telling us again…and again. Remember, readers use the first 30 pages to gauge how capable a writer is. And the main thing they’re judging is how quickly and efficiently you set up your story. In The Hangover, I think they wake up from their crazy night somewhere around page 20. You don’t want it to be any later than page 25 before we know what it is your character is after (see #2).

5) STAY UNDER 110 PAGES

This is a close cousin to number 2 and a huge point of contention between writers as well. But let’s move beyond my usual argument, which is that a 120 page script is going to inspire rage from a tired reader, and discuss the actual effects of a 110 page screenplay on your story. Keeping your script under 110 pages FORCES YOU TO CUT OUT ALL THE SHIT. That funny scene you like that has nothing to do with the story? You don’t need it. The fifth chase scene at the end of the second act? You don’t need it. Those 2 extra scenes I just mentioned above that tell us the exact same information we already know about your main character? You don’t need them. I know this may be hard to believe. But not everything you write is brilliant, or even necessary for that matter. Cutting your script down to 110 pages forces you to make tough decisions about what really matters. By making those cuts, you eliminate all the fat, and your script reads more like a “best of” than an “all of.” As for some of those famous names who like to pack on the extra pages, I’ll tell you what. For every script you sell or movie you make, you’re allowed 5 extra pages to play with, as your success indicates you now know what to do with those pages. Until then, keep it under 110. And bonus points if you keep it under 100.

6) CONFLICT

Does everyone in your script get along? Is the outside world kind to your characters? Do your characters skip through your story with nary a worry? Yeah, then your script has no conflict. I could write a whole book on conflict but here’s one of the easiest ways to create it. Have one character want something and another character want something else. Put them in a room together and, voila, you have conflict. If your characters DO happen to be good friends, or lovers, or married, or infatuated with each other, that’s fine, but then there better be some outside conflict weighing on them (Romeo and Juliet anyone?). Let me give you the best example of the difference between how conflict and no conflict affect a movie. Remember The Matrix? How Trinity wanted Neo but she couldn’t have him yet? Remember the tension between the two? How we wanted them to be together? How we could actually feel their desire behind every conversation? The conflict there was that the two couldn’t be together. Now look at The Matrix Reloaded and The Matrix Revolutions. Trinity and Neo are together. They’re always happy. And they’re always F’ING BORING AS HELL! The conflict is gone and therefore so is our interest. If your story isn’t packed with conflict, you don’t have a story.

7) OBSTACLES

Your script should have plenty of obstacles your main character encounters in pursuit of his goal. A big issue I see in a lot of bad scripts is that the main character’s road is too easy. The more obstacles you throw at your hero, the more interesting a script tends to be, because that’s why we come to the movies in the first place, to see how our hero heroically overcomes the problems he’s presented. He can’t be heroic if he doesn’t run into anything that tests his heroism. Go watch any of the Bourne movies to see how obstacles are consistently thrown at a character. And a nice side effect? Each obstacle creates conflict!

8) SURPRISE

A great script continually surprises you. Even if the story seems familiar, the characters’ actions and the twists and turns are consistently different from what we expected. The most boring scripts I read are ones where I have a good sense of what’s going to happen for the next 5 or 6 scenes. Remember, readers have read everrryyyyyything. So you really have to be proactive and outthink them to keep them on their toes. The Matrix is a great example of a script that continually surprises you. The first time you watched that movie (or read that script) you rarely had any idea where the story was going.

9) A TICKING TIME BOMB

Ticking time bombs can get a bad rap because they have such an artificial quality to them, but oh how important they are. What’s so great about them? They add * immediacy* to your story. If a character doesn’t have to achieve his goals right now, if he can achieve them next week or next year, then the goal really isn’t that important, is it? We want to watch a character that has to achieve his goal RIGHT NOW or else he loses everything. Sometimes ticking time bombs are clear as day (Hangover: They need to find Doug by noon on Saturday to get him back in time for his wedding), sometimes they’re more nuanced (Star Wars Luke needs to get the details of that battle station to the Rebel Alliance before they find and destroy the planet), but they’re there. If you don’t have a ticking time bomb in your script, you better have a damn good reason why.

10) STAKES

If your character achieves his ultimate goal, there needs to be a great reward. If your character fails to achieve his ultimate goal, there needs to be huge consequences. The best use of stakes is usually when a character’s situation is all or nothing. Rocky’s never going to get another shot at fighting the heavyweight champion of the world. This is it. Those stakes are damn high. If Wikus doesn’t get Christopher up to the mothership in District 9, he’s going to turn into a fucking alien. Those stakes are damn high. If all a character loses by not achieving his goal is a couple of days out of his life, that’s not very exciting, is it? And that’s because the stakes are too low.

11) HEART

We need to emotionally connect with your characters on some level for us to want to follow them for 110 minutes (NOT 120!). The best way to do this is to give your character a flaw, introduce a journey that tests that flaw, and then have him transform into a better person over the course of that journey. This is also known as having your character “arc.” When characters learn to become better people, it connects with an audience because it makes them believe that they can also change their flaws and become better people. In Knocked Up, Seth Rogan is a grade-A fuck-up, the most irresponsible person on the planet. So the journey forces him to face that head on, and learn to become responsible (so he can be a parent). You always want a little bit of heart in your script, whether it’s a drama, a comedy, or even horror.

12) A GREAT ENDING

Remember, your ending is what the reader leaves with. It is the last image they remember when they close your script. So it better leave a lasting impression. This is why specs like The Sixth Sense sell for 2 million bucks. If you go back into that script, there are actually quite a few slow areas. But you don’t remember them because the ending rocked. And I’m not saying you have to add a twist to every script you write. But make sure the ending satisfies us in some way, because if you leave us with a flat generic finale, we ain’t going to be texting our buddies saying, “Holy shit! You have to read this script right now!”

13) THE X-FACTOR

This last tip is the scariest of them all because it’s the one you have the least control over. It’s called the X-Factor. It is the unexplainable edge that great scripts have. Maybe it’s talent. Maybe the variables of your story came together in just the right way. Maybe you tap into the collective unconscious. A great script unfortunately has something unexplainable about it, and unfortunately, some of that comes down to luck. You could nail every single tip I’ve listed above and still have a script that’s missing something. The only advice I can give you to swing the dreaded X Factor in your favor is to write something you’re passionate about. Even if you’re writing Armageddon 2, create a character who’s going through the same trials and tribulations you are in life. You’ll then be able to connect with the character and, in turn, infuse your script with passion. Probably the best example of the X-factor’s influence on a script is American Beauty. A lot of people didn’t understand why they liked American Beauty. They just did. The Brigands of Rattleborge is another example. It just seeps into you for reasons unknown. I sometimes spend hours thinking about the X-Factor. How to quantify it. It’s the Holy Grail of screenwriting. Figure it out and you hold the key to writing great scripts for the rest of your life.

So there you have it. I’ve just given you the 13 keys to writing a great script. Now some of you have probably already come up with examples of great scripts that don’t contain these “rules.” And it’s true. Different stories have different requirements. So not every great script is going to contain all 13 of these elements. But you’ll be hard pressed to find a great script that doesn’t nail at least 10 of them. So now I’ll leave it up to you. What attributes do you consistently see in great scripts?

P.S. – Tomorrow I’ll post a review for a recent spec sale which you can read and break down to see if it has all 13 of these elements. So make sure to sign up for my Facebook Page or my Twitter so you’re updated when the post goes up. If I have to take the script link down, you’ll miss out.

Ahhh, a day off. Remember when we used to have those? I mean sure, technically us in America have Memorial Day today and don’t have work, but somewhere around 10 years ago holidays just became “get all the shit done you couldn’t get done otherwise” days. There is no such thing as a day off anymore. And that’s good news for you guys because it means that you still get a review! Yahoooo! So I’m going to leave the rest to Roger as he busts out a script with so many genres it needs its own multiplex. Here’s “Howl…”

Genre: Time-travelling werewolf Western (Okay, okay: Adventure, Horror, Science Fiction, Western)

Premise: A time-travelling Texas Ranger has spent the past 500 years hunting a particularly nasty werewolf. When he finally corners him in modern-day Texas, he’ll need the help of an unlikely posse to save the world from chaos.

About: This script was picked up in 2001 by Warner Brothers sans producer with Lemkin attached to direct. Back in October, I reviewed another Lemkin script, titled $$$$$$, about a modern day city war in Los Angeles. Lemkin’s writing credits include Red Planet, The Devil’s Advocate, and Lethal Weapon 4. Upon being asked about “Howl” and his opportunity to direct, “It still makes me laugh and I assume still terrifies them which is why it hasn’t happened.”

Writer: Jonathan Lemkin

Details: Third Draft

If I wasn’t a fan of Lemkin after reading $$$$$$, well, “Howl” won me over a lot sooner than the moment when Wanda, an ex-stripper and Waffle House waitress who has been recruited into a posse of werewolf hunters by a time-travelling Texas Ranger, dons a scant Red Riding Hood outfit and black fuck-me pumps and lures an army of werewolves into a seedy alley that has been converted into a kill box by the posse.

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[x] impressive

[ ] genius

Okay, so Amateur Month is officially OV-AH. That was fun. And at times scary because some of you are terrifying. It’s appropriate that today’s script is about nightmares because I think I’ll be having plenty due to Estrogen Deprived and Effscottfitz. If this is your first day back to Scriptshadow in awhile, you can go to Amateur Week here, Repped Week here, Favorites Week here, and of course, don’t forget to sign up for a tracking board if you haven’t already. I fixed the damn pricing thing I screwed up on, so it really is $44.25 now. I promise. — Hope you guys enjoyed this month as much as I sometimes did. We’ll have to do it again sometime. :)

Genre: Adventure/Children’s

Premise: A young boy teams up with a nightmare hunter to help him catch a monster that escaped from his dreams.

About: In 2002, Spielberg/Dreamworks picked up this very hot spec. The project unfortunately fell into a nightmare of its own (known as Development Hell) and unlike in the script, there was no one to save it. But Spielberg was a huge champion of the writers and tabbed them to write a couple of adaptations, including author Scott Lynch’s fantasy epic “The Lies of Locke Lamora,” about a likable con artist and his band of followers, and an original idea of Spielberg’s, “Charlie Dills.” (Don’t know what this is about – maybe It’s On The Grid knows???). But their adaptation with the best title by far, is the script they wrote for 1492 Pictures, titled: “Carpe Demon: Adventures of a Demon-Hunting Soccer Mom.”

Writers: The Brothers Hageman

Details: 99 pages (This is an early draft of the script. The situations, characters, and plot may change significantly by the time of the film’s release. This is not a definitive statement about the project, but rather an analysis of this unique draft as it pertains to the craft of screenwriting).

Wow, I don’t review many children’s scripts on the site. But I love a good high concept idea and this is about as high concept as they come. So hey, why not change it up?

I mean we were all kids once. I remember as a young tyke, watching “Tales From The Crypt” and one of the tales was about a dead guy who came back to get his birthday cake. He kept repeating the phrase, “I waaaant my caaaaake,” as his deteriorated skeleton of a face oozed worms and slime. That night, I sat scrunched up in the corner of my room with a hockey mask, a baseball bat, and any sharp object I could find, staring at my door til the sun came up, convinced Mr. I-Want-My-Cake Man was going to burst through that door and take me to Deathville.

Which is the perfect segue into today’s script, which is all about nightmares. Hugo Bearing is an 11 year old orphan (that’s old in orphan years btw) who’s plagued with horrifying dreams every night he goes to sleep. In his nightmares is the sickly evil spider-ish monstrosity known as Mister It. Mister It doesn’t just scare Hugo, he psychologically burrows into him, reminding him that no parents will ever come to adopt him, and that he will always be alone…forever.

Hugo’s best friend is the pudgy tag-a-long known as Asmus Fudge (note – All of the names in this screenplay are absolutely brilliant). There’s also the twins, Eye-Patch Pete, and the eternally cranky Benny. As Hugo is the oldest, he’s the one they all look up to. And for that reason, he’s reluctant to tell them about his secret – that his nightmares still haunt him.

So what’s the only thing worse than a nightmare? A nightmare that comes to life of course! And unfortunately for Hugo, Mister It escapes from his dreams into the real world. After he slithers away, Hugo meets 70 year old Atticus Marvel, a green trench-coated Nightmare Hunter. A cross between “Sherlock Holmes and Don Quixote,” Atticus is quite the badass for someone who gets a senior discount. He informs Hugo that they have a problem. Nightmares aren’t allowed to exist in the real world, and it’s their job to capture his nightmare and put it back where it belongs.

As their journey unfolds, Atticus explains the rules of Nightmare Hunting. Nightmare Hunters are kind of like Jedi. They’re called in when a nightmare gets unruly. Old stories you hear about dragons and goblins? Those were simply nightmares who escaped from people’s dreams. Nightmares are identified by their class. The higher the class, the more dangerous they are. For example there’s a Class 2 Trundle Trotter, there’s a Class 3 Obesian Snackpacker, and so on and so forth. (did I tell you these names were great or what?)

The reason it’s so important to find Hugo’s nightmare is that he’s a class 10, and class 10’s are capable of spawning other nightmares, which is exactly what starts happening. If they don’t get Mister It back into the dreamworld soon, the entire planet will be invaded by a nightmare army.

The first thing that popped out at me here was the sheer breadth of imagination. It really feels like these guys thought this world through. The mythology, while occasionally silly, is easy to buy into. I mean the whole “monsters throughout history being escaped nightmares” thing was really clever. I also loved the whole class system and how it operated. For example, nightmare class is dependent on how extraordinary the subject’s fear is. Mister It is a Class 10 because Hugo is so terrified of him.

I think this leads to my only beef, which is that maybe the characters aren’t as deep as they could be. I mean, Hugo’s situation is a perfect setup for a major character flaw. Hugo somehow needs to overcome his fear of Mister It in order to take him down. But I was never really sure what Hugo’s flaw was (what caused his fear), other than the very basic: he was scared of Mister It. Therefore, the character arc (Hugo overcoming his flaw) doesn’t resonate. Then again, this is a kid’s story. So maybe it doesn’t matter.

Another potential problem is the world the story takes place in. Even before the nightmares arrive, the town is described in a very fairy-tale like manner. I would imagine that throwing nightmares into that world wouldn’t provide enough of a contrast to take advantage of the concept. In other words, we may feel the impact more if the town were realistic. Throwing a dream into a world that’s already dreamy prevents them from sticking out, right? But again, this is a choice they went with and it’s not like it’s a dealbreaker.

I’m not easily won over by children’s movies. Whenever Harry Potter pops up on my boob tube, I can’t help but wish I’d run into him one day in a dark alley so I could punch that little zig-zag mark off his noggin. But this was cute. It won me over.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: So we’ve talked a few times about the mid-point and what a good mid-point achieves. Usually – not always, but usually – a midpoint is where you raise the stakes of the main goal. So if it’s a story about trying to get to the moon to save 3 astronauts who are trapped and running out of supplies, the midpoint might be the shuttle that’s going there blowing up a day before launch. Time’s running out. Their predicament is a thousand times worse than it was a day earlier. The stakes have been raised. The Nightmare Of Hugo Bearing has a nice midpoint. Initially the goal is to capture Mister It and put him back into the dreamworld. Difficult but still doable. Exactly halfway through the story (the midpoint) we learn that Mister It is a Class 10, which means he can spurn other nightmare creatures into existence. Talk about raising the stakes. Now, they not only have to capture THIS nightmare, they have to capture ALL of the nightmares he’s created. Go to the middle of your script right now. Do you dramatically raise the stakes of your story?