Search Results for: scriptshadow 250

Genre: Sports/Period/True Story

Premise: (from Black List) A law school graduate devises a betting system that exploits the glamorous, high-stakes sport of Jai Alai in 1970s Miami. Based on a true story.

About: (from his IMDB page) In 2008, Zachary Werner founded Bodega Pictures with Josh Ackerman and Ben Nurick. Together they produced over one hundred hours of television for top channels such as HGTV, Spike TV, and Food Network, as well as branded content. Zachary left Bodega in 2016 and partnered with his sister, Katharine Werner, to pursue scripted TV and film projects. This script finished in the 25th slot of the 2018 Black List.

Writer: Zachary and Katherine Werner

Details: 113 pages

A sports movie is one of those things that should always work. The goal is clear (win the game!). The stakes are easy to figure out (lose the game, lose everything). There are rules in each sport that provide clarity in what the characters are trying to accomplish. And there’s a structure to sports that intertwines pleasantly with the structure of screenwriting.

And yet, so many sports movies are AVERAGE. They’re never horrible (well, a few are). But they’re never amazing either. I mean, when’s the last great sports movie? Has there been one this century? Top contenders include The Blind Side, Million Dollar Baby, The Wrestler, and Creed.

I mean, you can make the argument that any one of those movies is “good.” But I don’t think anyone’s throwing them into the VCR for a repeat viewing in 2020.

Your lone defense against the cliche nature of sports movies is finding an angle that hasn’t been done before. And today’s script throws a sport at us that I hadn’t even heard of until I read this logline. So it has that going for it. But does it embed that sport inside a strong narrative? That’s what we’re going to find out.

It’s Miami, 1975. 26-year-old Ronnie Weiss has just graduated from law school and is ready to begin his life as a lawyer. But something’s bothering Ronnie about his career choice. Law is so boring.

Luckily, a new sport is taking over Miami – jai alai. It’s impossible to describe the sport but I’ll try. It’s like racketball meets Cricket meets a George Miller fever dream. But here’s the important part. Local bookies have started to accept bets on jai alai and since nobody understands the intricacies of the sport, that opens the door for a super-smart guy like Ronnie to exploit the numbers, allowing him to come up with a surefire way to win every time.

Ronnie can’t do it by himself so he recruits his crazy childhood best friend, Looney. He also enlists his new Cuban girlfriend to help, as well as a small army of bettors (so he doesn’t have to draw so much attention to himself). At first, Ronnie does this to pay off his dead father’s 250k gambling bet. But he takes care of that easily and now it becomes about making as many dollar bills as possible.

When there’s a fire at one of the betting boxes, the cleanup reveals how much Ronnie is raking in during these matches. That gets the Feds’ attention, forcing Ronnie and his core crew to flee to Connecticut, the only other place on the planet where you can bet these games. They start strong but Hartford doesn’t have the volume that Miami had and it isn’t long before the gig is up. And that’s pretty much it. End of movie!

This was a weird reading experience. On the one hand, you have this sport that we’ve never seen in movies before. On the other, you have a blatant Scorsese clone. From the main character narrating everything in that classic Scorsese-flick tenor to the voice over swap to the girlfriend happening at the exact same minute it happens in Goodfellas.

I don’t mean to get on my soapbox here but this sort of thing drives me nuts. Whenever you write in the exact same style as a famous storyteller with a unique voice – Tarantino, Sorkin, Diablo Cody, Martin Scorsese – the highest achievement your script can ever reach is a poor man’s version of that writer. A poor man’s Tarantino. A poor woman’s Diablo Cody. A poor man’s Scorsese.

This is not to say you’re incapable of writing well. But you have to realize that when you’re going up against the titans in the industry and trying to do exactly what they do BUT BETTER???? That’s a writing suicide mission. You can only do worse. Let me repeat that. YOU CAN ONLY DO WORSE.

If you sense my frustration, it’s because we all have this opportunity to write our own stories and tell those stories in our own unique voice. So why would you copy-paste the template of another well-known writer/movie to tell your story?

I get it. There have been 100+ years of movies. How much originality can we really bring to the table? I’m willing to have that conversation because I admit it’s difficult and one of the biggest challenges in screenwriting is bringing true originality to the page. But you have to TRY. Cause when you try, you come up with things like Parasite. You come up with things like 1917. You come up with the most heartbreaking movie of 2019, JoJo Rabbit.

So why do writers continue to write with the Scorsese template? Simple. Actors love playing these roles. You have two guaranteed “get a big actor” parts if these scripts are competently written. One for the flashy main character, who gets double the lines cause he’s narrating on top of leading the story. And two, the wacky friend, in this case, Looney. If you can get two big actors interested, you can get a huge director interested. And there ya go. So I get it. I get why writers do this.

But it’s a pet peeve of mine. I’m very much of the philosophy that you create things other people want to copy. Not copy things others have already created.

Despite that sidebar, the script wasn’t bad. It didn’t blow me away due to the aforementioned familiarity. But I enjoy stories where the main character has discovered a magic formula that nobody else has figured out yet. It’s why I liked the Moneyball script. Because you know the fall is coming – you know they’re going to figure you out sooner or later – and you have to keep reading to see how bad the crash is going to be.

Every once in a while, I’ll get behind a formulaic script. But only if the characters are amazing. And these characters were all characters we’ve seen before if you watched even one Scorsese film. So this definitely wasn’t for me.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: In a tragedy, the main character does not obtain his goal at the end. He will often lose everything, up to and including his life (Uncut Gems). But if he lives, make sure he learns something about being a good human. When it comes to these specific tragedies that deal with greed, the thing the character often learns is the value of those closest to him in his life. The people around you are always more important than a giant bank account.

Genre: Sci-Fi

Premise: The leaders of a planet journey to a new planet in a quest to gain control of a rare powerful substance called “spice.”

About: Dune is one of the biggest gambles in movie history. A 250+ million dollar production based on a 50 year old novel catered heavily to adults. It is dense and heady, two words studios detest. Nevertheless, they gave the film to “Blade Runner: 2049” director Denis Villeneuve and stacked it with the best cast this side of Once Upon a Time in Hollywood. Oscar Isaac, Timothee Chalamet, Zendaya, Jason Mamoa, Josh Brolin, Dave Bautista. The film was supposed to come out next month. But they were forced to push it to next fall due to the Corona virus. The original adaptation was done by screenwriting superstar Eric Roth. In a strange Hollywood twist, Jon Spaihts left a separate Dune TV series to write the final draft of the feature film.

Writer: Eric Roth and Denis Villeneuve (current revisions by Jon Spaihts) (based on the novel by Frank Herbert)

Details: 134 pages

My oh so conflicted Dune heart.

There isn’t a property I haven’t wanted to like more than Dune. A serious sprawling sci-fi fantasy story is something I should theoretically love. And yet every time I’ve tried to read the novels, I fantasize about getting a lobotomy.

But here’s what I’m hoping with the Dune script. I’m hoping that Roth and Spaihts have stripped away all of that boring muckety muck from the novel so that we get a cool stripped down enjoyable story. I don’t need 50 pages of backstory on how Greta Mogf’flox came to find her love for the art of noxela, that of the space ballet.

Give me a clear story, make it entertaining, and I’m in. Did that happen?

16 year old Paul belongs to a House that, I think, runs his planet. But Paul, along with his father, Duke Leto, and his mother, the prostitute Lady Jessica, only care about one thing – the SPICE! The spice is, essentially, a drug that allows for you to live a heightened life. It makes you healthier, smarter, even supernatural, since some people can use it to see into the future.

The problem is that the spice only grows on one planet – Arrakis. So all the surrounding planets come there to mine it. This is where things get confusing so I apologize if I get this wrong. I believe the people of Arrakis extend an invite to Duke and Paul, to come have a bigger controlling interest in the spice. They’re actually inviting a lot of Houses from neighboring planets there, including the House of Harkonnen, led by Duke’s rival, the 600 pound BARON VLADIMIR HARKONNEN.

Once they get to the planet, everything seems cool, if a little tense. When Duke and Paul learn that some spice miners are stranded in the desert with a potential giant Dune worm after them, they grab a hover ship and go save them. This is where they learn that mining spice is dangerous. At any moment a super worm can eat you up. I guess they like spice too!

Eventually, Paul, Duke, and Lady Jessica, learn that they’re being played by Baron Harkonnen! Harkonnen throws Paul and Jessica out in the middle of the desert while torturing Duke. He wants Duke to know that he’s eliminating his bloodline so that the Harkonnen can be the sole rulers of the spice! Talk about a spicy offer.

Back in the desert, Paul and his mom must avoid giant worms in the middle of the night. They barely survive until their clan’s top warrior, Duncan Idaho (Jason Mamoa), rescues them. They must get back to the city to stop the Harkonnen (along with the evil Emperor’s bloodthirsty army) from turning the planet of Dune into their own personal spice playground. Will they succeed? No one knows except for Timothee Chalamet!!!

I’m going to be straightforward with you here. This movie is in a LOT of trouble.

The issue is simple. It’s boring. At least for the first half of the movie it is. From there, it has some moments but mostly stays boring.

This was always my worry with Dune. I could never get into the book because I’d get bored quickly. The 1984 movie version of Dune was also boring. And now we have this film, which, even with the talent in front of and behind the camera, is stuck drawing from the same source material. So you have to wonder, is this story just boring?

Maybe we can answer that by asking what the screenwriting definition of boring is. Well, boring is in the eye of the beholder, of course. But there are certain concepts and setups and narrative choices that lend themselves to a more objectively boring experience. And Dune checks a lot of those boxes.

One, you have a ton of mythology and world-building. The more mythology there is, the more exposition you’re going to need. That means characters explaining things. The more your characters are explaining things, the less they’re ACTING UPON THINGS. Movies are about character ACTIONS. Not about WHAT THEY SAY. So if you’re doing something that’s keeping your characters from acting upon the world, you’re keeping them from engaging in a good story.

Next, you have a plot that moves slowly. There aren’t a lot of significant plot beats in your script. We cut from scene to scene without much forward movement in plot. Another way to put it is, after reading the tenth scene, a reader shouldn’t feel like they’re no closer to the purpose of the story than after reading the first scene.

Next, you have a lot of SAT scenes (Standing Around Talking). You guys know much I hate SAT scenes. It’s nearly impossible to keep an audience engaged when the only thing characters are doing is standing around talking to each other. And that’s the first 15 scenes of this script. It’s one SAT scene after another.

The only way this is going to work for audiences is if you’re one of those people who really loves deep rich mythologies. To you, it’s fun learning about this world. You don’t need a story to keep you engaged. But that’s a small percentage of moviegoers. Most moviegoers want a story.

Look no further than Dune’s fantasy movie cousin, Lord of the Rings. That film does it right. It sets up the mythology but it establishes the stakes, what the goal is, the journey ahead, how dangerous it would be, who needs to be involved, all very quickly. We then move into the journey, which ensures that the plot is always bopping along.

The first action scene in Dune doesn’t happen until the mid-point and I couldn’t even tell you what it was about. They hear some miners are in trouble. So they race out and save them. Encounter a sand worm. And survive.

Um, okay. That’s a scene. But here’s the problem. When they come back from that scene, EVERYTHING IS EXACTLY THE SAME. The story hasn’t moved forward. All that’s happened is they went off on this little side quest to save some people and now it’s back to bickering with the bureaucrats. Why am I 65 pages in to a 130 page script and I still don’t know the goal of our main characters??

Once Barron Von Fatso starts deceiving Paul and his family, things get a *little* more interesting. But not much. At least someone is finally acting (it’s a villain instead of a hero but, hey, something is better than nothing). But this plotline had its own issues. For example, we’re told from the start that Barron is up to something. So his deception was the most predictable twist ever.

Then, the plot is still static. Everything is happening in this one 50 mile range. Nobody’s going anywhere. We’re all standing around, ordering things, yelling at each other, people are sent out to the desert, they come back in from the desert. Contrast this with Star Wars or Lord of the Rings or even yesterday’s film, Love and Monsters. We’re moving forward in these movies. Dune, this purportedly giant universe, keeps all its characters in this tiny little area and has them play hide and seek with each other.

Ultimately, Dune is doomed by an old Scriptshadow mainstay. Burden of Investment. A high Burden of Investment is when the amount of information the reader is required to remember so outweighs the reward of remembering that information, that the experience doesn’t feel worth it. Or a more simplistic way to put it is, when a screenplay feels more like work than play, you’ve failed.

I will always respect the world-building that Frank Herbert did. I know how long that takes. But you still have to know how to tell a story. I’m not convinced that Herbert knew how to do that. Which is why everyone has such a tough time adapting this material.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Side-quests. Avoid “side-quests” in screenplays. They may be fun to do in video games. But if you’re sending your characters off on a 15 page sequence (12% of your entire movie), it better move the story forward. Here, we get Paul and his father going to save some stranded miners. Sure, it’s an okay scene. Yay for our heroes being heroic. But it didn’t move the plot along one inch. Contrast this with Obi-Wan and Luke going to Mos Eisley. That sequence moves the story forward because they’re trying to find a pilot in order to get to Alderaan. It actually gets them one step closer to their final goal. Maybe that’s why this script is a big fat fail. There’s no goal!!! Or, if there is, it’s buried underneath so much gobbledy-gook that only hardcore Dune lovers have put in enough effort to figure it out.

A few weeks ago I read the Black List rom-com that sold to Sony, Voicemails for Isabelle. It was easily the best rom-com I’ve read in years. The dialogue, in particular, was great. I said in that review that I would leave a voicemail for Leah and, what do you know, she replied! So we got on the phone and talked all things “Isabelle.” Leah was really forthcoming with her answers, which led to a great conversation. A little background here. Leah was an actress first. So you’ll see us referring to her acting throughout the interview. I also wanted a lot of dialogue advice so I asked a bunch of dialogue questions. Enjoy!

CR: The state of rom-coms in the last 15 years has been pretty bad. I think it’s because the genre is so inherently formulaic. How do you, Leah, approach the genre in order to stand out?

LM: I didn’t really know what I was doing and, in a lot of ways, that was my saving grace. Not just in rom-coms but in writing. I have no training in writing. And I agree with you. They’re so formulaic. I’ve seen a lot of rom-coms so I know the structure I have to follow in order for the audience not to get angry with me. But on some level I try to infuse it with some story about humans and sisters – my sister is my life and my love and my biggest supporter.

CR: And the inspiration for the story, I’m assuming.

LM: Yes, so what happened was I moved to LA to become an actress and my sister stayed in New York and I would leave these long voicemails to her late at night hoping to make her laugh. Or detail a terrible date. And in a lot of ways they became these confessional moments for me. The story was born out of that. I don’t know how to “write a rom-com.” All I focused on was telling my story. (for those curious, Leah’s sister is alive and well, so no tears need to be shed today)

CR: You reference a lot of rom-coms in the script so I think you know the genre better than you’re giving yourself credit for.

LM: Maybe! Yeah, I guess I do. I kinda feel it in my bones a little bit. Like I know at a certain point, “She needs to lose the guy here.”

CR: So your writing is instinctual?

LM: Yeah, that’s how I’d put it.

CR: How did you sell the script to Sony?

LM: This is going to be a long answer because it started back when I wrote and produced my first indie film, M.F.A. (a film about a rape at college). Cause I was running around asking everyone “How do you get an indie film financed?” And I would read all these sites and nobody would give me any concrete answers. So I would ask friends, “How do you do this?” And they would say, “Oh, you’ll find people,” And I would say, “But where are the people?” [laughs]

So I bought all the “How to Finance A Film” books and they weren’t very helpful either. None of them gave you a clear path on what you were supposed to do. Finally, I told everybody I knew that I was making a feature film and did they know anyone who’d be interested in investing in it. It was a slow process. Lots of dead ends. Lots of ‘this person leading to this person.’ But little bit by little bit we cobbled it together and shot it for $250,000, which included all the money I had at the time. The film got into South by Southwest and that gave me some legitimacy as a writer.

CR: Wow, you went all in.

LM: [laughs] I went all in in a way I do not recommend. Whenever filmmakers tell me they’re going to max out credit cards to make their film, on some level, I’m like, “Yeah! Do it or die!” On another level I’m like, “Self-care is important. Don’t do what I did.” [laughs] Because I came out of it so destroyed. I mean, in the midst of making that movie I was in so much pain because I was not eating. I was running on adrenaline. I ended up at the urgent care center. Anything that went wrong on the movie I took so personally in a way that you shouldn’t. I just want to say to people that I don’t think you should have to kill yourself for a movie.

CR: Yes, killing is bad.

LM: Right, and from that, I got my first literary agent. As well as my literary manager. And I got sent on the water bottle tour. Which is you go and you meet every single production company who liked your movie. And they’re all like, “What do you want to do next?” And I didn’t understand what I was doing at any of these places. I didn’t understand that I was supposed to be [laughs] pitching things. So I was sitting there thinking it was a friend date. I’m chatting and drinking my free coffee. So I said, “I don’t know what I wanna do next. Something cool I hope.” And I’m like, “Are you going to hire me now? What is happening?” And they all said, “Well, we’ll stay in contact.” And I was like, “Cool, we’ll stay in contact. Whatever that means.” [Carson laughs]

So during that tour, I met a producer named Becky Sanderman and we became really good friends. Becky pitched a TV show to me called, “What The F*ck, Glenn” about a mother dealing with her husband committing suicide. So I wrote that and that got me connected with Becky and Escape Artists, who are on the Sony lot. That led to me writing a father-daughter zombie project. And, for the first time in my life, I had a million voices giving me notes and I didn’t know how to handle it. Cause keep in mind, I was the only voice on M.F.A. I got so frustrated by the process that, in an act of rebellion, I wrote Voicemails for Isabelle. And one day Becky asked me if there was anything else I was working on and I told her about Voicemails and she said, “You are sending that to me as soon as you finish it.” And that’s what led to Sony buying it. I know that’s a long answer but I also know how frustrating it is for writers trying to understand how something gets sold so I wanted to be as detailed as possible.

CR: I’m not surprised it sold. I think you have a really strong voice, particularly your dialogue. Can you tell me your general approach to dialogue?

LM: My acting teacher John Rosenfeld always said, “Your characters are not as emotionally articulate as you.” People are not emotionally articulate most of the time. If you know that a character is heartbroken or sad, that doesn’t always come out as “heartbroken” and “sad.” People will try to play every emotion before they do that. They will get angry. They’ll be mean. They will turn it into a joke. So I very rarely play act a true darkness. We’re always trying to avoid that as humans. So a lot of times in my script where something sad has happened, there’ll be a scene that’s funny. I don’t do a lot of, “She cries and he holds her.” I don’t find that in my own life very often [laughs]. So I don’t write it.

Actors are also trained to observe people. So I’m always watching and listening and if I hear a good line, I write it down and make sure it gets in a script. For example, the other day a friend and I were looking at places to eat and we found this one restaurant that had these delicious looking noodles and he said, “Mmm, my mouth is hard.” I thought that was so funny. So the next time I have two characters in a food situation, they’re not going to say, “Mmm, that looks delicious.” They’re going to say, “Mmm, my mouth is hard.”

CR: That works in a comedy, obviously. But what about when you’re writing M.F.A., which is about a campus rape? How do you keep the dialogue interesting when you can’t depend on humor?

LM: Good question. I try to subvert familiar situations when I can. The scene that everybody brings up in M.F.A. is when the lead character, who’s been raped, goes to a “Feminists on Campus” meeting hoping for support. But when she goes to this gathering, she doesn’t get this outpouring of emotion or comfort. Instead, the girls were like, “Oh my God. Hash Tag Feminsim!” “We should do a bake sale.” “Oh yeah, we should provide a nailpolish where if you stick your finger in a drink it shows you if it’s been drugged.” “Ooh, good idea!” So it goes against what the main character is looking for in the scene and what the audience is expecting from the scene.

CR: What do you think the difference is between good and bad dialogue?

LM: Bad dialogue is often too literal. Too robotic. It has too much information. What is that word called? I have this list of words I always have to check.

CR: Exposition?

LM: Exposition! I’m a writer. I swear. That’s the thing that kills me. When there’s too much exposition. When a writer is doing too much telling and not enough showing. I’m such a big believer in show don’t tell.

CR: What do you mean by that because if you’re showing, you’re not writing dialogue.

LM: For example, if someone is heartbroken, they shouldn’t say, “I’m heartbroken.” If she’s in the room with the guy who broke her heart, you want to focus on how she won’t make eye contact. Or the guy doesn’t make eye contact. That sort of thing. No character who’s in pain should ever have to say that they’re in pain. We should be able to feel that through their actions.

I have this writer friend I’ve been helping and his characters explain everrrryyyyyyyy-thing. I’ve told him you need to cut all of this waaaaaaaay down. What isn’t being said is far more interesting than what is being said. Humans rarely talk about their emotions. They avoid emotions.

CR: Not a lot of writers are blessed with a natural comedic ability but they’re still required, at times, to write comedic scenes. How does one write funny dialogue?

LM: I don’t know. I tend to go with “TMI.” The things that would be so awkward if you said them but you’re still thinking them? Having your character say those things has always been a guide for me. A lot of times my characters are sort of irreverent and say the wrong thing. They very rarely say the right thing. If you could’ve done it over, you would’ve said it better. But there’s so much humor in the person reaching for the right thing and coming up short. There’s this great quote: “Funny people are just really observant.” I think that’s true.

One of my favorite movies is Little Miss Sunshine and my favorite scene is when the main girl says, “Grandpa, am I pretty?” And he says, “You’re the most beautiful girl I’ve ever seen in my whole life, I’m completely in love with you. And it’s not because you’re intelligent, it’s not because you’re nice, it’s completely because you’re so beautiful.” And I love that so much because it’s a little inappropriate for a grandpa to say to his granddaughter. And you’re not supposed to tell a little girl that her heart and her intelligence do not matter. But it’s so true and so honest that that’s how he handled the question. That is the kind of s*#t I want to write.

CR: My favorite scene in Voicemails was the meet-cute scene between Jill and Tyler. What I noticed about that scene was that the characters rarely said what you expected them to. They always seemed to say the opposite of what they were supposed to say. How did you approach that scene?

LM: I’ve never told this to anybody. When I got to LA as an actress, I started writing things secretly. I didn’t know how to write a screenplay but I understood how to write a scene. So I would write these little scenes. And I had written that meet-cute scene during that time. It wasn’t inspired by anything other than my own life – moving to Hollywood. Trying to navigate the town. Anyway, many years later when I was writing Voicemails, I stumbled across that document with all the old scenes in it and I found that scene and I thought, “Hmm, that’s pretty good!” And I pasted it into Voicemails without changing a whole lot. But that was a real revelation for me because I realized, you might not know how to write a script, per se, but it doesn’t mean that you don’t know how to write or that you don’t have talent as a writer. It’s really validating to hear that that was your favorite scene cause that’s one of the first things I ever wrote.

But yeah, if I analyze why that scene works now, I think it’s because they’re pushing each other, testing each other, and that’s where the fun banter comes from.

CR: Any last dialogue tips you can give us? For that writer out there who never gets complimented on their dialogue?

LM: Hmmm. People don’t generally speak in complete sentences. It’s difficult for people to have complete thoughts in the moment. They stutter. They start making their point only to realize they’ve messed up and double back. They struggle to get to the point. They say very inappropriate things along the way. The big thing for me is the verbal diarrhea character. Their own honesty is a plague for them. If it’s comedy, I’d say honesty is your best friend. The uglier and grosser and more grotesque the answer is, the better. And if it’s a dramatic scene, have your characters struggle with their pain. Struggle to hide the truth. The elephant in the room is the true emotion. But they should play EVERY OTHER emotion before going to that one. It’s so much more interesting to watch a person try not to cry than to watch a person crying.

And if I could give one last piece of advice, I would encourage writers to not wait around for permission. Try to get your own stuff made. And I’m not just talking about getting a film made because I know films are expensive. But I did a 7 episode web series when no one would give me the time of day. I wrote six short films with parts for me as an actress. I always hustled and never waited around. I think that’s the reason for any success I’ve had. You can do the same. You can put two actors in a car with some green screen and shoot it on an iPhone for nothing. What’s your excuse? You can do it!

Genre: Sci-Fi

Premise: A woman wakes up on a spaceship that has landed on a distant planet but has no memory of how she got there or why her uniform is covered in blood.

About: This came from the 2018 Hit List. I’ll paste the info from there about the writer: “Jonni is a German-Brazilian screenwriter who has seen every inch of the globe. Born in Switzerland and raised in Spain, he moved to London to get his degree in Film & Television Production. Since then, he’s worked in advertising and the broadcast department for the London Olympics. He’s recently found himself in New York where he received his MFA in writing from Tisch School of Arts. Since finishing ASH, Jonni is working on several projects for both film and TV.”

Writer: Jonni Remmler

Details: 108 pages

It’s been a rough few days. I suffered through ten hours of people singing and dancing about the Constitution. After that, I battled through a script that had more description in it than the Bible if it were translated by Leo Tolstoy. And while my gym has finally reopened, they’ve mandated that I wear the equivalent of a hazmat suit to work out. As if I didn’t have enough excuses not to go the gym already!

It was clear what was needed. The ultimate Scriptshadow picker-upper. The thing that got me juiced to start this website in the first place. The SCI-FI SPEC! To me, sci-fi and spec screenplays are the screenwriting world’s equivalent of peanut butter and jelly, the special sauce in an In and Out burger, the blinking “Hot Now” sign on the Krispy Kreme marquee.

I needed a shot of all those things directly into my bloodstream. So take a trip with me into outer space, Adam Driver Inside Llewyn Davis style. Link hands script friends and pour yourself a milky way sarsaparilla. Actually, pour the drink first, then link hands. We’re about to be blasted off into spec script nirvana. At least I hope we are…

28 year-old Riya has just woken up in a strange futuristic room. Her uniform is covered in blood, seemingly from a large gash in her forehead. The large metallic room has all its furniture pushed up against the only door. Riya stumbles over and looks through the window in the door. There’s a hallway with a large blood stain in it. Uh-oh, don’t want to go in there.

Luckily, there’s an automatic food processor in the room so Riya can easily stay fed. In the meantime, she tries to figure out how she got here, and we experience that with her via flashbacks. She remembers earth, something about the planet dying, and possibly being part of a crew that may have fled the planet.

Eventually, Riya gets out of the room and starts seeing dead members of her crew, who all seem to have been beaten to death. She also finds a window to the outside, and that’s when she realizes she’s on some distant volcanic planet. Riya continues to remember bits and pieces of her past and zeroes in on how one member of her team, Jones, is missing. She must be the one who’s killing everybody.

Before Riya can test this hypothesis, a man named Brion shows up. He says he came down from an orbiting ship that’s part of the same team she’s on. And that he’s here because SHE sent a distress call. Since a sand storm is moving in, they’ll have to wait two days to walk back to his shuttle.

In the meantime, they try to find Jones. But, of course, there is no Jones. (spoilers!) Brion ultimately reveals himself to be the killer. And to make things worse, he’s not even human. He’s an alien entity from this planet who has slipped inside Riya’s own brain! Which means that Brion isn’t even real. Brion, aka the alien, is Riya herself. Unable to process that she’s the killer, Riya asks what happens next. Brion explains that he will slowly consume all her brain functions and she’ll cease to exist. The End.

There’s nothing bad about this script. In fact, it would’ve easily passed the Last Screenplay Contest First 10 Pages Challenge. Waking up into a strange situation with no memory of how you got there is an easy way to quickly pull readers in.

But this is the definition of what all screenwriters should be wary of: the standard execution screenplay. Standard Execution is when you have a concept and you execute it the same way 99% of other screenwriters would’ve executed it.

A girl wakes up on a spaceship with amnesia.

There’s a mystery about someone killing crew members.

A mysterious man shows up outside. Wants to be let in. He appears to be friendly. But is he?

I’ve read this exact scenario in screenplays, maybe 250 times. Not long ago, we reviewed a script about how earth lost all its oxygen and a family in a bunker lets in a couple of strangers. So it’s a common setup. And to be clear, it’s used a lot because it works. But it only works when you play with the formula in unexpected ways.

And while I wouldn’t say this feels exactly like other films. It’s familiar enough that you’re always ahead of it. That’s where you don’t want to be as a writer. ESPECIALLY if it’s a mystery script like this one. Because the whole point of adding a mystery is to give the reader an unknown experience, something where they’re constantly trying to figure out what’s going on and then you keep pulling the rug out from under them.

I’m not sure anybody reads this and doesn’t know that Riya is the one who killed everyone long before the third act reveal occurs.

Another thing I wanted to point out was there’s this prevailing belief that budgetary constraints lead to more creative choices. When 90s vagabond director Robert Rodriquez was the hottest thing in Hollywood for making an $8000 movie, he would talk about this all the time.

But I’m not so sure this is true. Because while I read this, it felt like a lot of uninspired choices were made due to wanting to keep the movie cheap. Like the fact that there’s an alien involved, but he’s always strategically in human form. Humans are cheaper to shoot than aliens. But aliens are so much cooler than humans. So did budgetary constraints in this instance really make the movie better?

And now that we’ve had some distance from Robert Rodriquez’s filmmaking heyday, can we really say that the choices in his movies made them any better? He’s certainly good at making a lot of goofy nonsense. But maybe we shouldn’t be taking advice from a guy who’s basically become the D-level version of James Cameron.

All of this is to say that special effects are getting cheaper by the year. The Stagecraft technology that they use on The Mandalorian shows just how far a dollar can go these days. So yes, you want to be aware of budget as a screenwriter. I’m not telling you to write World War 7 set on Mars in 2744. But don’t let it handcuff you if you have a really cool idea in an otherwise low-budget film.

Again, I didn’t dislike this script. I always get excited when I read a sci-fi spec and I’m always looking for the writer who’s come up with the next Source Code. I’ll continue to champion everyone writing in this genre. But this script played out too predictably for me. It needed to take more chances in its plotting.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: One of the things you should be trying to do in a script is make your characters sound different from one another. But never do this at the expense of logic. So here, Brion comes in and he says things like, “You don’t remember none of that.” He likes to use the word “ain’t” occasionally. Astronauts are some of the most highly educated people in the world and, therefore, would never talk like this. So yes on talking differently. No on talking nonsensically. (note: this is *sort of* explained at the end but not convincingly enough to void this lesson).

Chronicles of Narnia meets The Most Dangerous Game and the power of a great concept

Genre: Fantasy/Thriller

Premise: Two hunters pay a strange mischievous man to travel into a world where you can hunt the creatures of fairy tales.

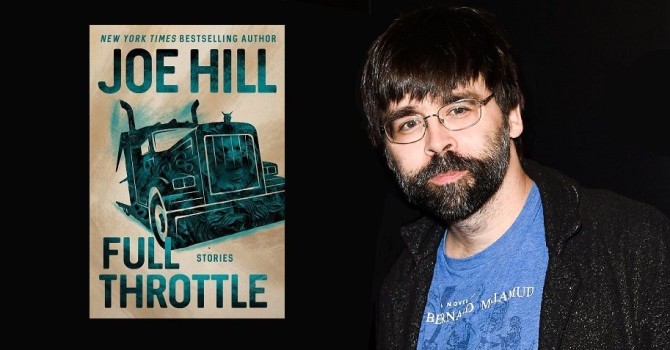

About: This short story by Stephen King’s son, Joe Hill, spawned a huge bidding war last year that Netflix threw the most money at. The short story can be found in Hill’s book of short stories, Full Throttle. It is being adapted by Jeremy Slater, who created The Umbrella Academy (for, yes, Netflix)

Writer: Joe

Details: Roughly 75 pages

I love big ideas!

We don’t get enough of them anymore.

This is a big idea. And it rides that elusive “same but different” line perfectly. It feels both familiar and fresh. If I could figure out what the secret sauce is to achieving that balance, I would be a billionaire. Instead, I see a bunch of ideas that are too much the same or too far out there.

“Faun” feels like a script that would’ve hit the market during the spec boom. And, no, it didn’t have to be a short story to get purchased. This is something that would’ve worked as a spec. That’s how good the idea is. So take heed – any one of you can sell a script if you come up with an idea as good as this.

The story follows a pharmaceutical billionaire named Stockton who loves to hunt big game. He’s friends with a “regular guy” named Fallows who also likes to hunt. Fallows used to be in the military so he’s seen his share of bloody spectacle.

The two are joined in Africa by their 18 year old sons, Peter (Stockton’s son) and Christian (Fallows’ son) to hunt some big game. Fallows ends up bagging a lion and then they all go back to Maine where Stockton has arranged a meeting with Mr. Charn, a strange middle-aged man.

Mr. Charn explains to Fallows that he runs a secret game-hunting business himself. But that it’s only available twice a year and it costs 250,000 dollars. Fallows is, of course, skeptical, even though Stockton’s already gone on this journey himself. So Mr. Charn shows a video tape of two men hunting and killing a “fawn,” which is a man with horns and blue furry legs.

It takes some convincing but Fallows eventually realizes it’s the real deal so he’s in. The next day the five of them go through a small door in Mr. Charn’s house. This door is the portal to this world. It is only open 2 days a year. The rest of the time, it’s a crawlspace. And, once you’re in the world, you need to be back by the end of the day or you’ll be stuck here for 9 months. And it won’t be you doing the hunting then. It’ll be them.

“Them” consists of every weird creature of lore you can think of. Fawns, fairies, centaurs, cyclops, and other monsters that have no names. It all seems impossibly perfect. The chance to kill something that only a handful of people on earth have ever killed. But Fallows soon learns that this land is unlike any he’s seen before and that even the tiniest mistake could result in death.

Joe Hill’s writing isn’t nearly as accessible as his father’s. Here’s the third paragraph of his story: “The baobab was old, nearly the size of a cottage, and had dry rot. The whole western face of the trunk was cored out. Hemingway Hunts had built the blind right into the ruin of the tree itself: a khaki tent, disguised by fans of tamarind. Inside were cots and a refrigerator with cold beer in it and a good Wi-Fi signal.”

The only thing I understood in that paragraph was beer and wi-fi. And this sort of scattershot writing style constantly creeps into Hill’s work. It’s not unclear. But it never feels as clear as it could be.

There was one point, early on, when our characters kill a lion. It’s a long scene. And, at the end of it, the lion leaps back up and nearly kills them. But Fallows is able to shoot it dead. It turns out the lion wasn’t as dead as they thought.

Then, after this, we get the line, “The Saan bushmen roared with laughter.” Ummm, what? This was the first time I was hearing of any bushmen. And the scene was 25 pages long. And, also, this isn’t exactly a moment that you would laugh at. They were all milliseconds away from dying. You’d get moments like that that were frustrating. If there’s bushmen around this whole time, let me know!

However, “Faun” survives this pitfall because the idea is so good. It’s a lot harder to screw up good ideas. Because what’s going on in producers and agents heads when they’re reading good concepts is, “That annoying part doesn’t matter because I can totally see this as a movie.” Contrast that with a dumb part that happens on some introspective character-driven indie script with no concept. That will usually end your chances with the agent right there.

What I admire most about this story is that it navigates the contradictory nature of its concept with ease. When you write a script like this, you’re basically asking the audience to root against your characters. It’s the same thing as a Friday the 13th movie. We’re rooting for Jason to kill them all. And that’s a lot harder to pull off than a traditional hero-driven story because you’re trying to make us stay interested in people we want to die.

Ideally, you want the middle ground. You want good people to be forced to do bad things. Like Breaking Bad. Or like the new project Edgar Wright signed onto, The Chain. That’s about people who just had a child kidnapped being forced to kidnap a child themselves in order to free their kid. It’s good people being forced to do a bad thing.

That’s not the case here. These are all bad people. They want to kill animals. They want to kill actual intelligent creatures. There’s nothing to root for with them. I’m actually surprised that Hill didn’t make one of the children reluctant. That would’ve given us someone to latch onto. But both Peter and Christian want blood as much as their fathers.

While reading this story, I had it at a double-worth-read. And then something happened that turned it into an impressive. Before you read on, I want you to imagine what might happen in a story like this for me to raise my ranking up to the rarely-given ‘impressive.’ What would you do with this story to get it there?

What Hill did was he didn’t rest on his laurels. He had plenty to work with already. He had an entire world full of unique creatures. However, what he did was set the characters up at a camp to prepare for the hunt, and then, just as they were about to go off, Fallows jams a knife into Stockton’s face and shoots Peter in his forehead.

At that moment I thought, “Now we have a movie.” We already had a movie. But this is a great writing move. You put all the focus on the outside danger, which makes the twist of “danger from within” that much more shocking. That really upped the ante of the story because now, in addition to having such a cool idea, I had no idea where the story was going to go. Which is exactly where I want to be as a reader.

This is a nice reminder that high concept ideas are not dead. They are alive and well. So, by all means, look into that idea notebook of yours and see if you have a couple of these stashed away. Even if they’re expensive. If they’re as good of an idea as this? And the writing is solid? It will sell. I can pretty much guarantee it.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[x] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: “Don’t cross the river!” I love this screenwriting tip. It always works. When you stick your hero unwittingly in the haunted house, have someone say, “Whatever you do, don’t open the red door by the bathroom.” And, the rest of the movie, we’re going to look forward to what’s behind the red door. Here we get the same thing. Mr. Charn warns Fallows and Stockton that, whatever you do, don’t cross the river! It’s dangerous over there. So guess what we’re looking forward to? That’s right. We’re on the edge of our seats to see what happens when they cross the river. “Don’t do [blah]” is a great way to create some anticipation in your reader.