I once read a script that started off with a courtroom scene. A dirty cop was being tried for shooting a young man. Meanwhile, another cop (we’ll call him “Officer Jake”) who was friends with the victim’s family, and who had known the victim, was called in as a character witness, to make a case that the young man who had been killed was a good guy and that he never would’ve done anything to warrant being shot. Officer Jake made his case on the stand, but the scene ended with the jury ruling in favor of the dirty cop, and both the family and Officer Jake left the courtroom devastated.

I want you to think about that scene for a second. How does it make you feel? Is it a good scene? A bad one? Do you feel like an adequate amount of drama was mined from that situation?

The reason I bring this up is because this is the kind of scene most writers write. It’s not a bad scene. But nor is it a scene that makes an impact. And this is something you should always be thinking about as a screenwriter. Is your scene just “there” or is it making an impact?

So how could we improve this scene to make it an “impact scene?” Well, here’s what I suggested to the writer. Keep Officer Jake’s relationship with the victim’s family the same. Make them very close. However, this time, make it so Officer Jake works in the same precinct as the cop on trial, and have their Captain force Officer Jake to be a character witness for the dirty cop – “take one for the team,” if you will.

Notice how all of a sudden, this scene becomes a lot better. We’re no longer experiencing something obvious. We’re experiencing something traumatizing. A character is being forced to help a man go free who he knows is guilty of murder in front of the family of the victim who he’s good friends with.

Think about how that scene plays out now. How Officer Jake has to force every lying word out of his mouth to help a man he despises, all while betraying his friends, who are staring him down from the audience.

So how do you create a scene like this? What’s the magic formula?

There are three parts to it. Let’s start with the first one. Don’t give your character something they want to do. Force them to do something they don’t. The idea here is that if your character is ever comfortable in a scene, it’s probably not a good scene (unless you’re setting up the character for a later fall – but that’s another discussion).

So let’s say your character, Nick, goes to a party he’s been looking forward to for awhile. If that party is comfortable every step of the way? You’re not doing your job as a writer. So maybe you have his evil ex-wife show up. Now the party is anything but comfortable, as our character has to navigate around the party to avoid her.

That’s screenwriting 101 stuff there.

Let’s move on to the second part – UP THE STAKES. Remember that nothing bad you do to your character is that bad if the stakes are low. In the scene I highlighted at the beginning of the article, a man is either going to prison for rest of his life or get away with murder. The stakes are very high.

So if we stay with our party theme, we might tweak it so that the party is now a networking event and Nick needs to land a big client who’s going to be there. Now that there’s something to lose, the scene has a bit more weight. His ex-wife isn’t just an annoying presence. She could screw up the deal.

Finally, we have our third component. And this, my friends, is the secret sauce – the thing that really makes these scenes impactful. Wanna know what it is?

MAKE IT PERSONAL

In my first example, that scene doesn’t play the same if Officer Jake isn’t friends with the family or if the family isn’t there at the trial. What makes the scene work is his personal relationship with the family and the fact that he has to betray them right in front of their eyes.

So, in our “party” scene, an option might be for Nick to finally make his way to the company he’s trying to land as a client, only to see, at the last second, his ex-wife step up. He then realizes that she works for the company he has to land, which means he has to suck up to the very woman he hates more than anything to get the deal done.

I’m not in love with that option. I’d probably keep working on it until I found something better. But that’s the idea behind the formula. Force your character to do things they don’t want to do. Up the stakes if possible. And turbo charge it by making it personal.

Another famous example of this is The Good Wife. A wife who sacrificed her life to support her State’s Attorney husband finds out he’s been cheating on her over the years with dozens of hookers. She hates this man more than anything. Yet she’s asked to stand next to him at a news conference and tell the world that she supports him and still loves him. That’s the essence of this device. A woman who has to support a great husband? Boring. A woman who has to support a terrible one? Impactful.

Just remember that if Sophie doesn’t have to make a choice, you don’t have a scene.

If you’re looking for notes on your latest script, I offer screenplay consultations. If you want me to break down your script and tell you how to fix it, e-mail me at Carsonreeves1@gmail.com with the subject line “CONSULTATION” and we’ll get started!

Genre: Horror/Fantasy

Premise: After a lonely young woman is murdered, she awakens as one of the “Goners,” a group of outcasts who struggle to deal with their post-life existence.

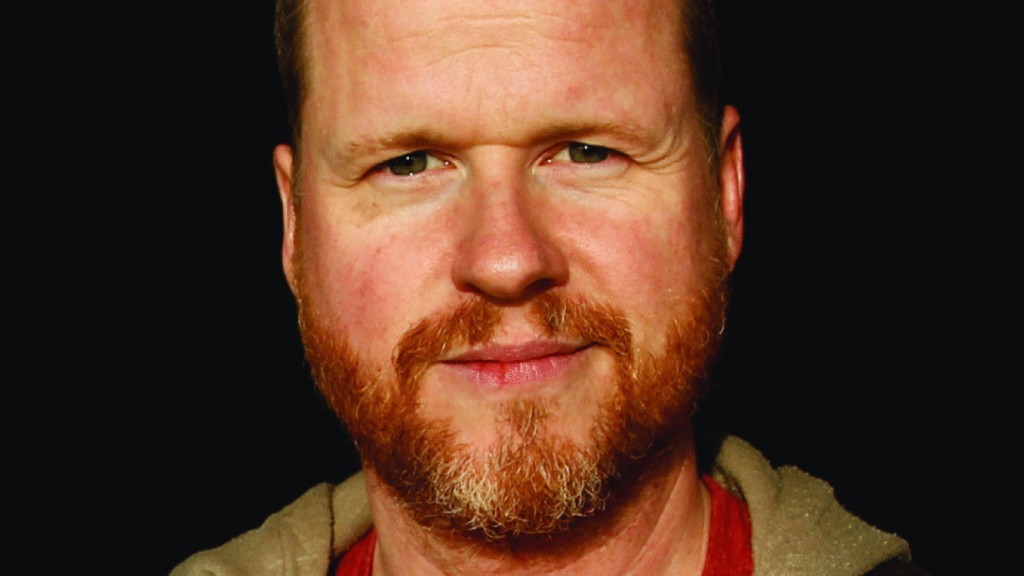

About: Joss Whedon had such a terrible experience directing the Avengers sequel that he disappeared from the public eye for two years. Whedon finally arrived out of his cave a month ago, announcing he’d be taking on the feature adaptation of Batgirl. Then, just this week, it was announced that Whedon would be taking over directing duties (mainly post) on Justice League due to a tragedy in the Snyder family. Whedon joins this week’s Alien theme, as he happens to be the writer of Alien: Resurrection. Today’s Whedon script was written in 2005, which would place it two years after Buffy the Vampire Slayer finished its run. It never got made, and we’re going to find out today if it should’ve.

Writer: Joss Whedon

Details: 120 pages

Whedon is an interesting writer. I’ve always seen him as a guy who thrives in the television format but struggles in the feature department. Look no further than the project he brought to both mediums, Buffy the Vampire Slayer. Buffy was a dud on the big screen but a downright phenomenon on television. That can’t be coincidence.

Regardless of whether you like or hate Whedon’s style, there’s no denying he creates an insane obsession with his fans. And, really, that’s all you’re looking for as a writer. You’re trying to find that fanbase. You’re never going to make everyone happy. But if you write in a unique voice and find stories that you tell well, you’ll find a group of people who love your stuff.

Mia is a 30-something lonely cubicle worker whose only happiness comes from her cat, Bonkers. So when Mia’s co-worker, Joanne, invites Mia out for drinks, her first instinct is to blow her off. But then, when she goes to pick Bonkers up from the vet that night, she’s informed that he died. Devastated, but afraid of being alone all night, she goes out.

That turns out to be a bad move, as a man picks her up from the bar and later murders her. We follow Mia’s body to the morgue, where she eventually wakes up. Just as she starts to understand where she is, two creepy clay men slither out of the air vents. Mia’s able to escape through a floor vent, and soon after finds herself in the sewer.

As the clay men continue to chase her, a badass goth chick named Violet shows up and takes them out. Violet leads Mia back to her hideout, where we meet the rest of her crew, the “Goners.” This includes the upbeat Punch, the resentful Shiva, the homeless-looking Black Pepper, and 10 year old Japanese twins who don’t speak English.

Violet lays out the rules for Mia. She’s dead. And those clay people? The group doesn’t know who they are. Just that when you see them, you run away. Oh, and living people can see you, but they forget you within seconds, fallout from being so forgettable in real life.

What Violet can’t tell Mia is what they’re all doing here. But after they’re attacked by the clay men again, Violet thinks Mia’s murder might have something to do with the increased aggression. So they go back to the scene of the crime – the bar – to look for clues. They eventually realize it was the FedEx guy from work who killed her.

Meanwhile, the clay creatures keep multiplying, which Violet is convinced is because some porthole has been opened or something. Which means Mia and the other Goners will have to do what they were never able to do in real life – team up – and defeat the evil before their team is wiped out for good.

I was surprised by how much I liked this.

I freaking LOVED the first 10 pages, before I knew this was a fantasy movie. I thought Whedon might’ve been tackling real life for once, and the manner in which we meet this lonely girl then see her mercilessly killed was incredibly affecting. Mia was such a nice person. I was legit upset when she died.

Even when she wakes up again, I thought this was going to be a serious horror film in the vein of The Sixth Sense, where we follow this dead girl around as she tries to find her murderer.

But Whedon is in love with the ass-kicking 18-25 female character. You’re unlikely to read a Whedon script where that trope doesn’t get applied somehow. So I was bummed when Violet arrived, cause I figured everything would now go down in typical Whedon punch-kick-quip fashion.

But the mythology ends up being solid. The stuff with them being forgotten in life and needing to join together in death, and each having unique powers and the mystery of these clay people…

Let me put it this way. When writers haven’t figured out their mythology, you can tell. Everything is murky. This is what they’re saying about the new Pirates film where there’s a compass with rules and different types of pirates have rules and some pirates can come onto land and some can’t and nobody really knows why. The point is – we know when you’re adding on mythology to fill in plot holes as opposed to building the mythology first, making sure it’s solid, then building a story on top of that. Which is what Goners does. I mean, this script is Buffy meets The Matrix with a splash of The Frighteners, which, in my opinion, is a cool as hell idea.

And I’ll say this. While I don’t like hearing Whedon’s quip-heavy dialogue on-screen… boy is his dialogue pleasant to read on the page. It’s got this flow to it that I can appreciate after reading five scripts in a row where the dialogue is clunky or robotic or lifeless.

Here’s an early scene, where two cops are trying to figure out how Mia was killed after recovering her body from a lake…

“This is not the kind of girl that picks up a guy in a bar.”

“Until the day she does! One night she says ‘Hey, I’m a pathetic spinster with a nothing job and no friends and I’m gonna get crazy for a change.’ She rolls the dice, comes up snake eyes.”

“Did you just say ‘Spinster?’”

“The woman clearly had no real life at—“

“You’re a very old man.”

“Old enough to pin you down and take a crap on your head, you give me grief, Hirsh, you punk—“

“She’s looking very good. Can’t have been under for more’n a few hours. (beat) I’m saying she knows the guy. He comes in here and pulls her out, or maybe at the bar but… where’s the damn cat?”

“He probably took the cat. He killed her for her cat.”

“This is a fresh kill. He’s not far away. I’m leaving a car here.”

“Yeah, he might come back for the kibbles. Stay alert, officer. The motive was cat.”

Not only does he have fun with the dialogue, but notice the DIFFERENCES in the characters. One’s young. One’s old. One’s serious. One’s joking around. New writers don’t think about differences, so a lot of their characters end up saying similar things. That’s how easy it is to write bad dialogue. You don’t know why you can’t make the characters sound more interesting. Well, had you thought about their differences, their dialogue is naturally going to sound different. I don’t even have to introduce these cops to you and you know who they are. The dialogue tells us that.

The script is structurally perfect, too. The first act is us getting to know Mia so we care about her, the murder (inciting incident), and then her arrival into the afterlife. The first half of the second act is “fun and games,” to use an old Blake Snyder term. We meet the team. There’s some clay men battles. The midpoint is Violet realizing that Mia’s arrival has opened up some hole that’s brought more evil into the world. This leads to a goal – find out who murdered you since they might have something to do with this. Mia does that. This leads to them learning about the bigger threat, which propels us into the third act, where our team must vanquish that threat.

But just as a screenwriting lesson, I recommend anyone who’s having trouble with creating likable characters to read the first 10 pages of this script. It’s screenwriting perfection in how you create a hero who’s loveable and who every reader is going to want to follow no matter where that character goes.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[xx] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Exploit your character’s unique traits to create unique moments. Every character you write should have something unique about them. Once you’ve established that, look for ways to exploit it. For example, Mia’s post-life power is that she can turn into water. So there’s this moment, later on, where she grabs her murderer and pulls his face into her body, which is now water. So his face is inside of her, and he’s drowning. I’d never seen a moment quite like that before, and it came about because Whedon exploited Mia’s most unique trait. And this doesn’t just have to be superpowers. Walter White (Breaking Bad) was a chemistry teacher. In one episode, he uses his knowledge of chemistry to create an impromptu bomb and escape a drug dealer. Find the unique trait. Exploit it!

Genre: Drama

Premise: The true story of the kidnapping of the richest man in the world’s grandson, and the subsequent refusal by John Paul Getty to pay the ransom.

About: If you got the feeling after Alien Covenant that Ridley Scott wasn’t interested in making an Alien movie, today’s project may be the reason why, as this film is set up to win Scott some Oscars. The “All The Money in the World” package just sold at Cannes, and will star Mark Wahlberg, Kevin Spacey, and Michelle Williams. The script is written by long-time scribe David Scarpa, whose most recent credit is The Day The Earth Stood Still (2008) and whose script for this film landed on the upper half of the 2015 Black List.

Writer: David Scarpa

Details: 120 pages

The most I knew about J. Paul Getty before today was that he built a museum in Los Angeles that’s a bitch to get up to.

So it was fun to learn all about the Citizen Kane’esque figure. Getty was the man who figured out how to get oil out of the Saudi Arabian desert. He negotiated rights to the land the oil was on, built the super tankers that would transport the oil to other countries, and built gas stations wherever those tankers would sail to.

You can imagine how much money someone would make owning the rights to oil the second it came out of the ground to the second it entered your gas tank.

Like most obscenely rich people, Getty was a quirky dude. He didn’t trust anybody, as he believed they were all after his money. And he was a notorious penny-pincher, going so far as to clean his own clothes at hotels, refusing to pay the dollar the hotel charged to do it.

J Paul Getty had lots of children (the man had 5 wives) so he didn’t have time to be close to all of them. One of his first sons, Paul, was discarded like a cheap sweatshirt, and grew up poor.

When Paul’s wife, Gail, got sick of living day to day, she demanded Paul get in touch with his father and ask for money. When Paul refused, Gail wrote the letter herself. Surprisingly, Getty welcomed them in with open arms, and the family went from Baltic Avenue to Park Place.

But the money went to Paul’s head, destroying his marriage with Gail, leaving Gail alone with their children, the oldest of whom was (also named) Paul. Gail settled down in Rome with the kids. Then one night, when teenage Paul was out partying, a group of men grabbed him off the street and kidnapped him.

They would later call Gail with what, they believed, was a bargain asking price. 17 million. The world went running to Getty. What was he going to do?? Getty shocked the media by stating simply, “I’m not paying it.” Instead, he hired a fixer, Fletcher Chace, to look into the kidnapping, then went back to operating his business.

Meanwhile, Gail was in a no-win situation. The kidnappers assumed she was rich, yet she barely had enough money for her own living expenses. When a police investigation uncovered information that Paul might have faked his kidnapping to con money out of his grandfather, everyone went their separate ways, assuming Paul would eventually come back home.

This led to Paul being stuck in his kidnapper’s lair for months, his mother the only one who believed he was in any danger. But her reach was so limited, that there was nothing she could do but wait. Wait to find out if her son would come home dead or alive.

All The Money In the World (a reference to Gail saying she couldn’t pay the ransom and the kidnapper replying, “Get it from your father-in-law. He has all the money in the world.”) starts out strong, with a clever first act that begins with the kidnapping.

This is followed by a flashback that explains who J. Paul Getty is, and how his estranged son, Paul, and Paul’s wife, Gail, came to work for him, which then led to their divorce, which then led to Gail raising the children on her own.

This section solidified the relationship between Gail and Paul, which was necessary since she’s the only person in the story who cares about his return.

However, the script stalls once Getty refuses to pay his son’s ransom since there’s nowhere left for the story to go. Nobody’s pursuing anything anymore. As a result, the majority of the second act amounts to people waiting around.

The only characters with active goals are the kidnappers. Their desire to get their money is the only thing left pushing the story along. And yet their scenes lack any notable drama, since they remain cordial with Paul all the way up to the final act.

The fixer, Chace, has the potential to be a cool character, but since Getty cuts his balls off, he’s relegated to being an emotional support system for Gail.

All of this leaves the story in a perpetual state of waiting. And, to be frank, it was difficult to care. We’re essentially watching a kidnap story where no one wants to save the victim. You know what it reminded me of? That weird Angelina Jolie movie, The Changeling? You know the one where you weren’t sure what you were supposed to be feeling or what was really going on? This story leaves you with that same type of feeling.

True life may be stranger than fiction, but it’s also less dramatic. Building a story around a kidnapping where no one goes after the victim is, literally, the most undramatic thing you can do.

The lone standout character in the script is Getty himself. And you can smell Spacey chomping at the bit to play a penny-pinching billionaire. He’s also one of the most dialogue-friendly characters you can write.

For newbies out there, the “professor” character is a great device to inject awesome dialogue into your story. “Professor” characters are characters who are always using history to make a point. These little stories not only add an element of suspense to each interaction, but a splash of fun as well.

For example, late in the script, Saudi Arabia ups the price of oil tenfold, making Getty ten times richer than he already was. Chace comes to him and says, surely you’ll pay the ransom now. Instead of saying, “I don’t have the money to spare at the moment,” Getty points out that he’s over-leveraged, offering, “Do you know how Jesse Livermore died? He was the greatest speculator in stocks ever to work on Wall Street. He blew his brains out in a coat check room after he lost every penny he had. That’s how fast a man’s fortune can turn. Don’t you see? I’ve never been more vulnerable financially than I am right now.”

So add a professor character if you want some cool dialogue.

Unfortunately, none of the other characters were as interesting as Getty. I couldn’t figure Chace out. He didn’t seem to be as good at his job as was advertised. Gail did look for ways to save her son, but you always felt like she could be doing more.

Then there was Paul. Clearly, Paul was a mess in real life. He did drugs. He partied all night. He hung out with sketchy people. I suspect this is the real reason nobody looked into Paul’s kidnapping. Because he was a deadbeat loser who brought it upon himself. But Paul’s sketchy lifestyle is never revealed to us, I suspect because, if it was, you wouldn’t have a movie. Since the concept is predicated on us sympathizing with Paul, we must erase all traces of Paul being a bad person. It all felt a bit manipulative.

There’s a movie in here somewhere. But I couldn’t find it in this draft.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Sandwich your boring parts. Any time you have a section filled with exposition or backstory, a smart move is to sandwich that section. For example, the first act here is backstory on the Gettys. Instead of immediately jumping into that section, Scarpa wisely SANDWICHES it between the kidnapping. We see the kidnapping right away, we then get the full backstory, then afterwards, we’re right back to the kidnapping.

Genre: Sci-Fi

Premise: A colonist ship follows a distress call to a nearby planet where a mysterious entity awaits them.

About: Alien Covenant is the… 6th film in the franchise? 7th? Ahh, who’s counting anymore. The film opened this weekend at #1 at the box office with 36 million alien bucks. It was scripted by “All You Need is Kill” writer Dante Harper and the man responsible for writing all the recent James Bond films, John Logan. Ridley Scott is back with the bullhorn. And Michael Fassbender has returned in clone-form, as he’s playing two parts in the film.

Writers: Dante Harper and John Logan (story by Jack Paglen and Michael Green)

I have a soft spot for the Alien franchise.

Aliens was one of those experiences that shaped my love of movies. And when something is wedged that deeply into your nostalgic subconscious, anything else you throw at me in the same universe I’m going to see it. And that, in a nutshell, is why the movie business is so successful. Once they get you on something, they can market that something to you for the rest of your life.

But the sad truth is, the Alien franchise has been terrible since Aliens. I don’t care what anybody says – Fincher’s Alien 3 was an embarrassment. Then there was that “Am I really seeing what I’m seeing??” Winona Ryder Alien 4 catastrophe. From there, they went from “We don’t know what we’re doing” to “We’ve officially given up,” dropping that Aliens vs. Predator abomination on us. It got ugly, folks. It got real ugly.

Then Ridley Scott returned to the franchise and, finally, it seemed like chest-bursting might be cool again. Indeed, Prometheus brought a lot of fun back to Alien. But it still came nowhere close to the quality of the first and second films. Then came a confusing array of events that, at one point, had District 9 director Neil Blomkamp helming a parallel Alien se-prequel that went back to Alien’s roots (bringing back the series’ star – Ripley) while Ridley Scott, who couldn’t care less about Alien for 40 years all of a sudden wanted to make four more Alien films.

WTF?

If there ever was a moment that symbolized the clumsy architecture of this franchise, that would be it. So it shouldn’t be surprising that Alien Covenant is just that – clumsy. What starts off as a pretty awesome flick turns into… well… I don’t even know what. But knowing screenwriting like I do, I’d distill it down to “writers who ran out of ideas.”

And look, I’m not ignorant here. I understand the studio priority ladder. It’s so hard to match up a director’s schedule with a star’s schedule with a studio’s schedule. So when those three worlds match? You pull the trigger no matter what state the script is in. You have to. Because if you don’t, the movie never gets made at all. And what good is a script if it never gets made into a movie?

It’s then up to big-name screenwriters to accomplish the impossible – construct a great original screenplay in the amount of time it usually takes you to finish an outline. Despite being hired to fail, these writers go into these projects with the best of intentions – hoping to pull off a miracle. Sadly, they rarely do. Which is why we get so many movies like Alien: Covenant.

For those of you who have no intention of seeing the film (and you shouldn’t) the plot starts out pretty basic. A colony ship 7 years from their destination receives a mysterious transmission from a nearby solar system and decide to go inspect it, partly because this planet never appeared on their colony research and they figure, hey, maybe we can cut 7 years off our journey and colonize this planet instead!

Once on the planet, they go looking for the signal location, and a couple of colonists sniff up alien dust. Within minutes, these colonists are sick, and when our infamous aliens burst out of their bodies, a mad scramble ensues on the landing ship, resulting in a catastrophic accident that blows the ship up.

Up until this point, I was onboard. But then things get weird. Like, really weird. While getting attacked by other aliens, a… a jedi [????] shows up, scares off the aliens somehow, and tells the colonists to follow him. Mysterious Jedi Dude (I call him this because he was wearing Obi-Wan Kenobi’s robe for some reason) brings us back to some giant spooky circle town that’s been long since abandoned, and when he takes off his hood, we realize it’s David, the psychopath robot from Prometheus.

Meanwhile, the colonists have their own robot, Walter, who’s an upgraded version of David. Walter immediately senses that David has gone off the deep end, but is still intrigued by him, to the tune of the two sharing a couple of sex scenes together. I’m not kidding. I mean, they don’t have sex, but they basically have sex. It’s too weird to explain and too dumb to recap so you’ll have to seek it out yourself to get the full dumbass experience.

Eventually we learn that David’s been breeding alien embryos and is excited to have some new humans to experiment on. So the killing begins, and this is where things get stupider and stupider, culminating in one of the oddest action scenes I’ve ever witnessed, where a woman who’s had three lines up until this point becomes the movie’s main action star, willingly jumping out on the side of an out-of-control ship to try and kill an alien.

There’s more – a sort of extra final act – but I’m not sure why they included it, since everybody already knew what was going to happen. It’s bad writing on about every level.

So let’s talk about how this movie fell apart, because I’m fascinated by how these things happen. For starters, there was no main character. While I’ve discussed the no-win situation you place yourself in when you don’t build your story around a hero, it’s not a script killer. In fact, the very first Alien didn’t have a main character either! Ripley didn’t emerge as the “hero” until the very end of that film.

But there’s a reason why that worked and this didn’t. The first film was CONTAINED. So it kept our focus laser tight on the situation at hand. The tight nature of that story allowed for a more fluid situation to emerge with the characters.

Alien Covenant was the opposite. It was all over the place. It was part contained horror, part ‘group explores a planet,’ part mystery, part philosophical drama. The film was trying to be so many things that messiness was already embedded into its DNA. Trying to pack more messy (identifying our main character on page 100) onto already messy made things feel, well, too messy.

To Alien Covenant’s credit, it was attempting to be more than your average summer blockbuster. It posed big questions about God and creation and why are we here. You have to give the writers credit for not throwing another by-the-numbers popcorn flick at us. But you only want to pose big questions if you have the time it requires to come up with answers. If you try to answer the biggest questions humanity has ever asked with 2 weeks left before production starts, you probably aren’t going to come up with satisfying answers.

At some point, the writers realized the answers weren’t coming, gave up, and started using screenwriter shock-tactic tricks (robots giving each other blowjobs) to deviate your focus from the fact that nothing in the story made sense.

One of the easiest ways to tell that a writer has run out of time (or doesn’t care) is when characters start acting illogically. Why would the Captain (Billy Crudup) willingly follow a robot that he knows is systematically killing his crew into a room full of gestating alien eggs? “Take a closer look,” David says as the Captain checks on an egg. “You can trust me.” And the Captain then takes a closer look. That really happens.

And there isn’t just one of these instances. They happen again and again.

The only reason I’m not giving this film a “What the hell did I just watch?” is because I loved the first 30 minutes. Otherwise, this movie is awful. Pulling in 36 million is 20% less than what Prometheus opened at. So I’m hoping that’s it for this franchise. And yet, like the aliens in the movie, these franchises never seem to die. They had the audacity, the other day, to announce another Terminator film after Terminator: Genisys.

[ ] What the hell did I just watch?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the price of admission

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: You have to be willing to move off your original idea if it’s not working. I get the feeling that Scott went into this wanting to create a philosophical science-fiction piece that was bigger than aliens chasing people down corridors. That’s a noble pursuit. But good writers know that stories are living breathing things. Sometimes what you thought would work ends up not working at all, and a direction you’d never considered all of a sudden makes the story a lot better. Be malleable as a writer. In the end, it’s about finding the best story, even if that’s not the story you set out to write.

Anybody who lives on the West Coast, and especially people who live here in Southern California, know, that if you’re ever feeling down, if you’re ever feeling blue, there’s one place you can go that will always lift your spirits.

I’m talking about In and Out.

In and Out is a privately owned fast food franchise that separated itself from the competition by using a business model that is basically the opposite of McDonalds. “Make two things perfectly and they will come.” That’s right, In and Out only offers two things: burgers and fries. But they do it so damn well that you never want anything else.

In fact, the simplicity of the menu is what allows In and Out to be so yummy. Because they only make two things, they don’t have to freeze any of their food. They bring it in fresh every morning. That means every time you order a meal at In and Out, it’s guaranteed fresh.

But did you know that In and Out can also make you a great screenwriter?

I bet you didn’t. But read on, my friends. Because you’re about to have your mind blown and your taste buds satiated.

Every story you tell has two forces constantly at play.

The things coming IN.

And the things going OUT.

Let’s start with OUT since it’s the more familiar of the two. Whenever I talk about ACTIVE characters, I’m talking about characters who are goal-driven, who seek out objectives. Every time a character does this, they are pushing OUT onto the plot. Deadpool seeks revenge on his torturer. He’s pushing OUT on the plot. Michelle tries to escape the bunker in 10 Cloverfield Lane? She’s pushing OUT on the plot.

And this holds true for much smaller actions as well. If Michelle’s goal in a scene is to palm a knife during dinner she can later use against Howard, she’s pushing OUT onto the plot.

IN is, obviously, the opposite. This is when the plot throws things at your character. If a character is saving money to go to college (OUT) and a robber breaks in and steals all her money, that’s plot coming IN at your character. If a friend of hers is in an accident and needs to borrow a large portion of her savings, that’s plot coming IN. If the college calls and says they need the money now or they’ll have to give the spot up to someone else, that’s plot coming IN.

And that’s how storytelling works. Your hero is either pushing OUT on the plot or plot is sending things IN at the character. So why is this important? I’ll tell you why. Because one of the more common mistakes I see in screenwriting is screenwriters doing only one or the other.

For example, let’s say a screenwriter writes an OUT-dominated screenplay. A young female UFC fighter is trying to win the title. We could see her training (OUT), hire a coach (OUT), get a sponsorship (OUT), win all her warm-up fights (OUT), buy a bigger house (OUT). So let me ask you, does that sound like a compelling story? Of course not. We need some INS. We need her to bust up her dominant wrist in an accident (IN), her old crew turn against her (IN), her mom gets sick (IN), the heavyweight champion decide she doesn’t want to fight our protagonist (IN). The INs are what cause all the obstacles, all the conflict. Without INs, your story is a simplistic march to boredomville.

Consequently, scripts suck if they’re all IN and no OUT. If your character stays in all day, bored with the world, and then he gets an eviction notice because he hasn’t paid his rent (IN), then later his car gets towed (IN), then his ex-wife calls him for the first time in a year and says he owes her 10 grand in child support (IN) and then even if something good happens to him, like some random shop owner offers him a job (IN)… we’re going to get frustrated because our hero isn’t putting anything OUT into the story.

As you can probably guess by my tone, the best scripts have the IN and OUT in equal proportion.

One of the most powerful devices in a screenplay is to send your character off on an OUT and then, during the scene, hit them with an IN. So let’s say a Fortune 500 CEO is going out to accept a major award, an OUT scene. The audience then gets prepped for that to happen. That’s where their mind is. However, when our CEO is chatting with people before the award, a couple of men in dark suits come up, informing him that they’re from the SEC. They explain that they’re going to let our CEO accept his award so as not to embarrass him, but right afterwards, they’re going to arrest him for embezzlement. This is a total IN when we weren’t expecting one.

I’ve also discovered that if you are going to favor one over the other, INs get the nod, since INs are disruptors. They throw your hero off his path, force him to act, which is always when a character is most interesting.

But you want to use both aggressively. It’s an easy way to add more pop to a bland script. If something feels boring, add more INs and add more OUTs!

Now excuse me while I go order the Carson special: Two Double-Doubles and some Animal Style fries.

See you at the counter!