Time to compare a plot-driven script with an anti-plot-driven script

There are two things I can promise you. Number one, In and Out has the most consistently good cheeseburgers on the planet. And two, there has never been, nor ever will there be, a screenplay analyst who compares Spider-Man Across the Spiderverse and Sanctuary. I am the only one.

That’s right. I finally watched Spider-Man: Across The Spiderverse, the animated sequel to Spiderman: Into the Spiderverse.

It’s always been hard for me to take these animated movies seriously. I think, “If it was a good script, they’d make it live-action.” It brings me back to all those Disney animated movie sequels that went straight to video. “Simba Learns Salsa.” “The Little Mermaid and Paco the Parrot.” “Abu and Jafar: Oops What Happened to My Flying Carpet?”

But this Spiderman movie did really well, it got great critic scores, and it’s been recommended to me by a handful of people.

So I watched it.

And I didn’t like it.

I just don’t think these movies are for me, man. It took me 45 minutes just to get used to the style of animation, which looked like a 3-D movie without the 3-D glasses. I had to put 100% of my focus into not getting annoyed by the faded muddy backgrounds.

Once I got past that, I could see what fans of the film liked. It’s a surprisingly heartfelt film. There’s a lot of emotion here, explored mainly between children and their fathers. When you’re young and trying to find your way in life, you can feel confused and lonely. And during those times, you really need your parents. And when they don’t see things the way you do, you feel more alienated than ever. I thought this movie captured that well.

I also thought the soundtrack was amazing. Whoever was in charge of the music of this movie deserves an Academy award because, like I said, most of the time I was annoyed by the animation. But, even then, I was feeling things because the music did such a great job of pulling me in.

For those who haven’t seen it, Spiderverse has an extremely complicated plot, so I’m going to simplify it for you. Miles and Gwen are both “Spider-Man” in their own universes. When a spotted villain who has the power to create black holes that he can seamlessly jump through, trips up the multiverse circuitry, a series of “canon” malfunctions happen, putting the multiverse in danger.

Gwen takes Miles to “Spider-Verse” which is an MIB like headquarters where the millions of different Spider-Men across the universes hang out. It’s there where Miles learns that, in every universe, a Spider-Man loses a loved one. And Miles’s timeline is about to kill off his loved one, his father.

If Miles saves his father, it destroys the multiverse and everything in it. If he doesn’t save his father, well, then his father’s dead. Obviously, he’s going to try and save his dad. Except that a million Spider-Men are determined to stop him. So he has to pull out all the spider-stops if he has any chance at protecting daddy.

While you process all that, let’s jump into the other movie I saw this weekend, an indie movie called, “Sanctuary.”

The reason I even know about this film is that it has two of my favorite young actors in it: Margaret Qualley (playing Rebecca) and Christopher Abbott (playing Hal). The writer, Micah Bloomberg, has a bit of pedigree. He’s the guy who created the buzzy Homecoming podcast, which went on to become a big Amazon adaptation (Sam Esmail, Julia Roberts), which he also wrote. The director, Zachary Wigon, directed one episode of that series, which, I’m guessing, is how they connected.

Sanctuary blew me away with its opening act. Granted, it works better if you don’t know anything about the movie going in (that’s your cue to go watch it now and come back). But it’s really clever stuff, which is one of the more elusive tools in the screenwriter toolkit. Are you clever? Cause if you can consistently outsmart the reader, you can gain a lot of fans.

In the first act, Hal, a seemingly well-off businessman, is visited in his ritzy hotel room by Rebecca, a lawyer from the firm that’s considering Hal for their new CEO job. Rebecca is here to do some last-minute diligence for the firm to see if Hal is right for the job.

They sit down at a small boardroom table and she begins to question him on things. Have you ever been arrested? Do you have any history of alcohol abuse? Questions like that. Much of the dialogue is sophisticated with splashes of humor.

Rebecca: Do you abuse prescription drugs?

Hal: Do I abuse prescription drugs?

Rebecca: Is that question confusing?

Hal: I take prescription drugs. I don’t know how they feel about it.

About midway through the interview, Hal starts to get annoyed. Only after some back-and-forth do we realize that not everything is as it seems. Rebecca is not a lawyer. She’s a dominatrix. Hal is not gunning for a CEO job at another corporation. He’s her client. And Hal has specifically written this script out for Rebecca ahead of time. What he’s getting annoyed by is that she’s going off-script.

This is another tool every writer should have in their toolkit – the scene-flip. We all think we understand what’s happening in a scene. But then, midway through the scene, the writer flips the script (literally) and it turns out we’re reading something completely different.

This is an especially effective device for the first scene of your screenplay. The reader has zero context for what they’re watching, which means they have no choice but to take everything you’re telling them at face value. This is what allows you to trick them so easily with the scene-flip.

After that opening scene, we see Hal and Rebecca, together, in a celebration of sorts. It seems to be part of their routine. After they get done with a session, they order in food, eat, and chat. I guess it makes it a little less icky than if he immediately kicks her out. She *has* been preparing for three weeks.

When this second scene arrives, we get another “flip” of sorts. They change into completely different people. He’s more fun and casual. She’s more shy and careful. This is not only a fun screenwriting thing to do. It pulls double-duty because this stuff is like crack to actors. They get to play two-roles for the price of one.

In less than 30 minutes, this screenplay has completely captivated me.

Okay, so, what does this have to do with Spider-Man?

What’s so fascinating to me is that these movies are attempting to do completely different things when it comes to plot. And you can extrapolate this to most movies that are either “Hollywood” or “Indie.” But you can really see the differences with these movies because they represent the extremes.

Spider-Man is drowning in plot. It has so many different universes. It has all these Spider-Men we have to get to know. We have the villain and what he’s trying to do – which requires an entire subplot to set it up. We have a “Super” Spider-Man guy, Miguel, who’s leading the charge on fixing the multiverse. I don’t think we get to the midpoint before we learn what this movie is really about – Spider-Man saving his dad.

Meanwhile, with Sanctuary, there’s virtually no plot. After that opening scene, we learn that Hal’s father, a hotel magnate, just died. And he’s taking over the company. Much of what Hal and Rebecca have done in her dominatrix sessions is help him be assertive – learn to stand up for himself and go after what he wants. He tells her that he’s ending their relationship because he’s finally “ready.” She wants to be fairly compensated for getting him to this place, so she starts demanding money. And that’s pretty much it. That’s the plot.

Note how, with Spider-Man, the writers’ primary job is to figure out how to get all of the plot stuff (via exposition) out of the way as soon as possible so the movie can just have fun. But because there’s so much to set up, it takes them all the way until the midpoint. Only then can Spiderverse breathe.

Meanwhile, since Sanctuary barely has any plot, it runs out of it fast and must start searching for it. We get a five minute “searching for a hidden camera” scene at the 30 minute mark because the writer has to figure out how to fill up at least 90 pages.

It’s funny, when you think about it. When a movie like Spider-Man Across the Spiderverse dies, it is because it has too much going on. There’s too much to manage. The reader gets so frustrated trying to keep track of everything, they give up. Movies like Sanctuary die for the opposite reason. There isn’t enough meat on the bone. The plot is so thin that the script inevitably finds itself in these giant valleys searching for a reason to exist.

This is a long way of me saying, you want to know which kind of writer you are because then you can write the kinds of scripts you’re good at. If you’re more of a technical writer who’s good at managing giant chunks of exposition that you’re able to easily hide in your script, the big Hollywood movie is more for you. If you’re a more creative writer who is good at finding powerful character moments so that you don’t miss a beat when the plot runs thin, then character pieces are probably for you.

As for these movies, neither of them are perfect. I’ll give Spider-Man this: It felt original. Which was a nice change from these live-action superhero movies that have all felt the same lately. And then with Sanctuary, it does struggle with those no-plot valleys. But Bloomberg knows how to write. He knows how to keep the character conflict going during those softer plot moments, enough to keep us invested. For that reason, Sanctuary will probably end up on my Top 10 list this year.

We check out two First Page Entries and glean what it takes to write a great first page.

Instead of doing a Logline Showdown this month, we are doing a FIRST PAGE SHOWDOWN. You send me the first page of your script, I put the best five first pages up on the site, the readers of the site vote for their favorite, the winner gets a script review the following Friday.

Can you follow in the success of the wonderful Wayward Son? Only way to find out is to enter!

What: First Page Showdown

Send in: Title, Genre, Logline, and a PDF of the first page of your script

Deadline: Thursday, September 21st, 10:00pm Pacific Time

Where: e-mail all entries to carsonreeves3@gmail.com

As I’ve begun to read through the first page submissions, I noticed something. Some writers had sent in whatever first page was already in their script. Other writers re-thought their first scene to allow for the best first page possible. For example, there are a lot of submissions where a murder has just taken place.

What’s interesting about this is that, in a few of the cases, I’d already read the entire script. So I knew where the scenes were going. I knew that, in one case specifically, even though the first page was mundane, the scene itself would build to a fun climactic moment on page 7.

There isn’t anything wrong with writing a slow-build first scene. I actually think slow-build scenes work better than scenes that shock you from the outset.

HOWEVER.

I also realized from this exercise just how crucial it is to grab the reader right away. Does a great slow-build page 7 climax matter if they never get past the first page? For this reason, you should seriously consider reworking your first scene so that it has a great first page. I mean, how many times have you seen readers of this site give up on first pages in the Showdowns? 17 million?

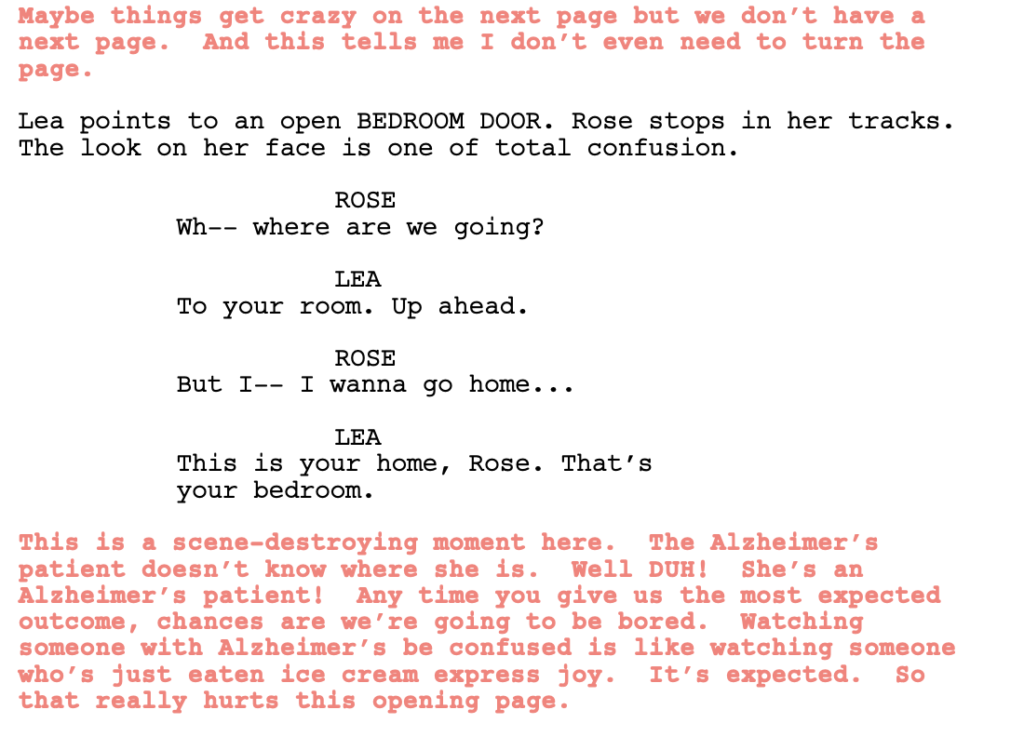

With that in mind, I’m going to give you two first page entries. Me featuring these has no bearing on their potential inclusion in the showdown. I just want to share with you what a reader looks at as he’s reading a first page.

Before we rethink this scene, I want to acknowledge that maybe something earth-shattering happens on page 2. But taking that out of the equation, how could we have made this opening page better?

Before we rethink this scene, I want to acknowledge that maybe something earth-shattering happens on page 2. But taking that out of the equation, how could we have made this opening page better?

Well, we have an old person with dementia. We have a staircase. Why would you have them walk UP that staircase with help when you could have them walk DOWN that staircase with no help? Isn’t that a scarier more suspenseful scenario?

Maybe the opening shot is on Lea and her “Registered Dementia Specialist” tag asleep in a chair. Rose is up and walking along the second-floor hallway, looking out of it. She gets to the stairs, looks down them with a sense of confusion and fear. We highlight how delicate Rose is, how she would crumble if she fell. Then we milk that suspense. Is she going to walk down the stairs? Hang on that question for as long as possible.

Even if she didn’t start the walk down the stairs, that’s still a great first page. I GUARANTEE YOU every single executive in Hollywood who read that first page would read the second. And if they read the second, there’s a chance they’ll read the third. And the fourth. And so on.

Maybe our writer has a better scene than this written if we’d just kept reading. But this is the first page contest. You gotta hook us right away.

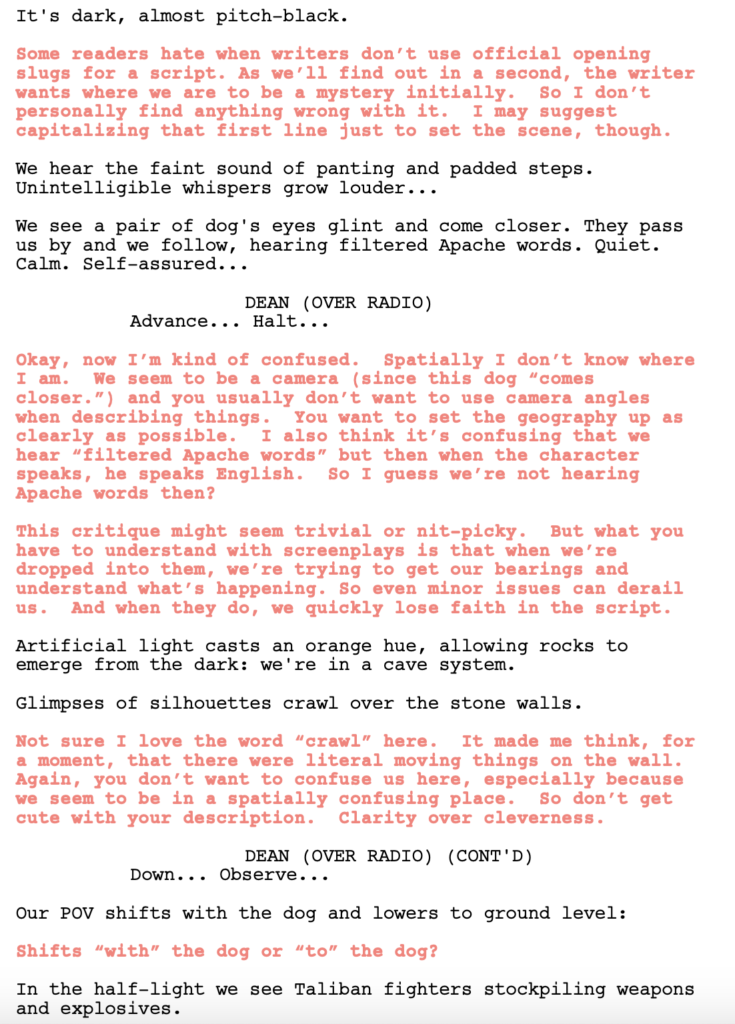

Here’s our second entry.

Would I keep reading here? Probably not. I give credit to the writer for starting off the story with something happening. This opening page promises major conflict if we keep reading. But for me it comes down to subject matter. I’ve read a million scripts about Afghanistan. What are you giving me that’s different here?

Would I keep reading here? Probably not. I give credit to the writer for starting off the story with something happening. This opening page promises major conflict if we keep reading. But for me it comes down to subject matter. I’ve read a million scripts about Afghanistan. What are you giving me that’s different here?

“But Carson, it’s only one page! I can’t give you something different on one page!” Yes you can! You can give me a quick page beat that’s unexpected, that’s unique, that focuses on something original that we don’t usually see in these screenplays. Competition is tough, guys. You don’t get to say, “Well, what you’re asking for is too much.” YOU’RE GOING UP AGAINST HUNDREDS OF THOUSANDS OF OTHER WRITERS. Decent first pages, which this is, aren’t enough.

I need you to embody that. Imagine just how much competition you have. And let that push your bar up higher. Cause that’s all this is. We all set a bar for ourselves. If that bar is too low, you’re not going to push yourself. So put it up high. Make it impossible for someone not to turn the page after your first page.

Keep sending those first pages in for First Page Showdown!

Is today’s screenplay the spec script return of the slick high-concept sci-fi thriller?

Genre: Sci-Fi Thriller

Premise: A down-on-his-luck former getaway driver comes into possession of a mysterious watch that allows the user to go back in time by one minute. As he starts to uncover its uses and gets pulled into one last heist by his former crew, a dangerous group after the technology gets on his tail and will stop at nothing to get the watch back.

About: Today’s writer just got his first produced credit this year, with “Murder City.” “Undo” seems to cover similar ground… but with time travel! Simmons’s script finished on last year’s Black List.

Writer: Will Simmons

Details: 110 pages

Michael B. Jordan and his cool shirt for Vince?

Michael B. Jordan and his cool shirt for Vince?

Thank Hootie and the Blowfish for this next tip. When it comes to writing high-concept stuff, one of your biggest allies is time. Time provides the key, not only to an unlimited number of high concept ideas, but to ideas that are cheap to produce, and therefore compelling to producers.

From going back in time to going forward in time to looping time to condensing time. There was that sci-fi script that sold to Amazon where future cops use a process of slowing down time by as much as 5000% at active crime scenes in order to take down the bad guys.

“Time why you punish me. Like a wave bashing into the shore. You wash away my dreams.” Poignant, Hootie. Poignant, indeed.

Vince is a former NASCAR driver. The only oil he changes these days is for his Toyota Prius to make sure he’s good to go for his next Uber drive. Yes, Vince is now an Uber driver. Sadly, the only joy he gets is in trying to find faster routes than the ones Google Maps assigns him.

Vince is perpetually late, which his girlfriend has had enough of. When he isn’t able to get her to her flight on time, she dumps him. While still at the airport, a scategorical Russian man named Gene lands in Vince’s car and gives him 300 bucks cash to “drive.”

Not long after they leave the airport, a truck starts bashing Vince’s poor Prius. A man in the truck pulls a gun and shoots Vince dead. But then Gene presses a button on a special watch he’s wearing and we go back in time 60 seconds. This time Gene is able to warn Vince about the gun, which helps Vince survive.

But only temporarily. The truck collides with the Prius again, badly injuring Gene. With his dying breath, he takes the special watch off, puts it on Vince’s wrist (where it locks onto him), and tells Vince to “find Anna.” Gene dies and Vince slams his petal to the metal.

Vince is able to get to his old criminal buddy, Benji’s, house. Benji will allow him to store the car with the dead body here only if Vince agrees to be the wheelman in Benji’s next Brink’s truck heist. Vince reluctantly agrees (what choice does he have?) And off they go. But the heist is a setup. The entire car full of Benji’s team is slaughtered. Except that Vince is able to reverse time and escape.

Benji is now freaked out and kicks Vince out of his home. That’s when Vince realizes, “Wait a minute, I control time!” So he goes to the nearest casino and starts racking up cash. It’s there where he meets Pike, the guy who funded Gene’s research. Pike wants that watch back. And he’ll do anything to get it. Can Vince use the one ace up his sleeve (1 minute rewinds) to escape Pike? Or is Vince in way over his head?

“Undo” is a script I would’ve written when I first started screenwriting.

It’s so far in my lane that I may as well be using Bentley-level cruise control.

But Simmons makes some of the same mistakes I used to make with these scripts, the first of which is being too casual with the execution.

Any time you’re asking the reader to accept a fake reality that you’ve created, you run the risk of them not buying what you’re selling. Usually, what does you in, is being too casual with the execution.

Take, for example, a scene from the first act where Benji recruits Vince to be the driver in his latest heist. When the rest of the crew shows up, one of them says, wow, we’re so lucky. Vince is the best wheelman in the world.

IN THE WORLD!

That’s a pretty big statement, right?

Except that four scenes earlier, we watched Vince RUN OUT OF GAS while trying to get his girlfriend to the airport. I don’t know much about being a getaway driver. But I’m pretty sure that if I was a good getaway driver, one of the things I’d probably monitor is THE GAS!!!!!

That was a minor thing though.

This next one was major.

Benji initially freaks out when Vince shows up with a dead guy in his car. Benji wants to know how long ago Vince lost his tail so that he can be sure no one’s followed him here. Vince tells him it was miles ago, he’s clear, and so Benji lets him in.

They then start doing research on Gene (the dead guy) and find out he’s FORMER KGB!!!! What’s Benji’s reaction to this? He shrugs his shoulders. Hmm, that’s interesting. Doesn’t bat an eye.

Let me think out loud here for a second. A minute ago, Benji was worried about some second-tier street thug maybe following Vince and figuring out where Benji lives. But Benji has no problems with a DEAD KGB AGENT IN HIS HOME?????!!! I’m thinking on the scale of “this is a problem,” that’s about a million times worse than a Latin King.

When the writer doesn’t consider these things, it bothers me. Because it tells me he’s not really living in the world of his screenplay. He’s more concerned with moving the plot along. It’s too casual. And casual execution kills.

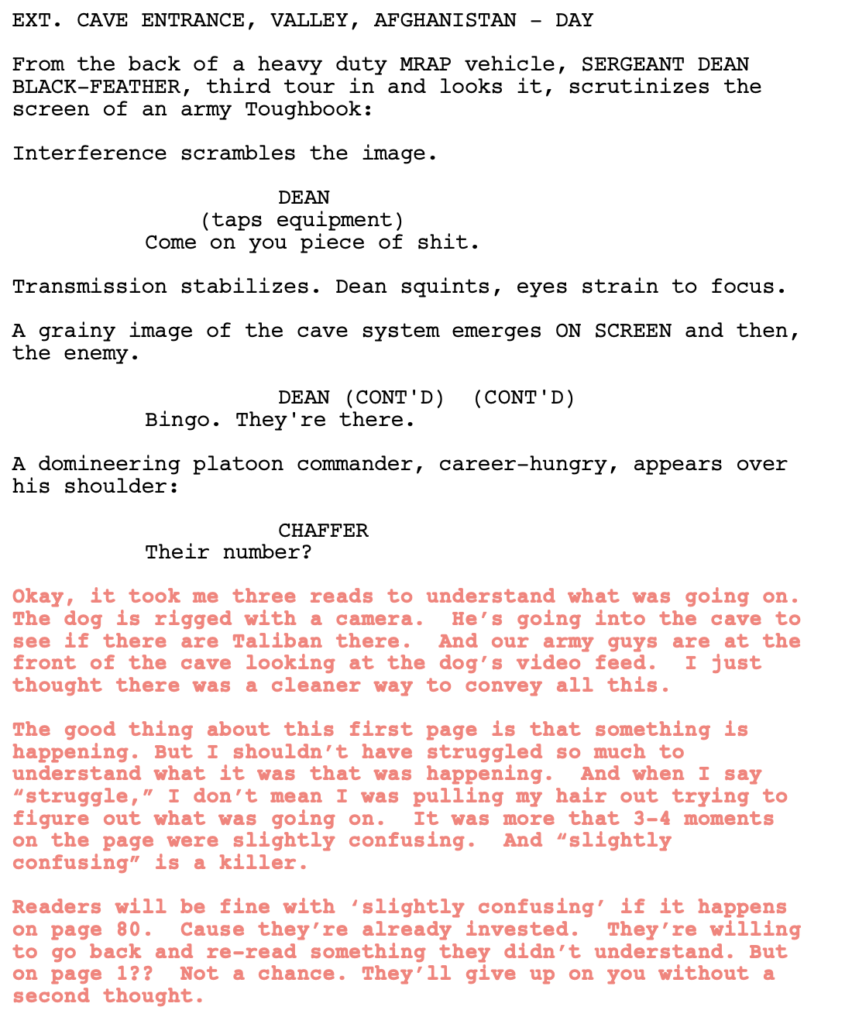

The real reason people are coming to see this movie, though, is to see it deliver on the promise of its premise. Do we get cool “can’t see’em in any other movie” sequences involving this one-minute time jump?

I would say the script does okay in this department. I’m always looking for those 2-3 scenes that really knock it out of the park – scenes that I could never have thought of in a million years. Cause that’s when you know the writer is really dialed into his premise. He’s seeing it in ways nobody else sees it.

Which should be the case for every script ever written. The writer should be so entrenched in his idea, that he’s already thought of the 30 different scenes that the average writer would’ve thought up regarding the 1-minute time jump and not used any. Because he’s going deeper. He’s going to give you the stuff nobody would’ve thought of.

There’s a scene in the second act where Vince charges up on two of Pike’s guys sitting outside of his home, catching them off-guard. Vince still doesn’t know the rules of this world yet or what’s going on.

To me, this was the best exploration of the premise in the script. It felt like we were genuinely using the 1 minute time loop in a clever way.

But after that, all the uses of the loop were expected, which basically boils down to a bunch of times where Vince is dying after getting shot and then getting one more minute back. There was one other interesting scenario where Vince was getting attacked on all sides, wherever he ran, so he barely escapes a gun to his head, gets outside, gets nearly killed there as well, and he has to make a decision because, if he goes back in time one minute, it will be where the guy has a gun to his head. So he’s dead either way.

THAT stuff I like. Because any time you give your character a choice where both options are bad, audiences are interested in seeing which one he chooses.

I know I’m beating a dead horse here but the way that you separate yourself from the pack is not to take a fun premise and execute it averagely. Or slightly above-average. The way to separate yourself is to do the hard work and really come up with the kind of execution that knocks the reader out. Makes them say, ‘Whoa’ every ten pages, a la Keanu Reeves. I never got the sense that Simmons gave me everything he had. So even though this was a decent script, it wasn’t for me.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: A scene that will always work is to give your character a choice where both options are bad. The higher the stakes of the choice, the more compelling the scenario will be. Too many writers give their characters choices where there’s a good choice and a bad choice. How interesting is that? If we know what the character is going to choose, you haven’t made both options bad enough. You want to create the kind of choice where *you’re* not even sure which option you would choose.

Is “Suits” a perfectly constructed pilot?

Recently, I read an article that the two biggest streaming shows in America were Gray’s Anatomy and NCIS.

I’ve never personally met anyone who’s seen an episode of NCIS so, naturally, this was confusing to me.

I was also confused when, amidst a bottomless pit of shows on Netflix, many of which have had giant advertising campaigns, that the show that had become the most popular was one that had ended four years ago, “Suits.”

We have been led to believe that the TV landscape is dominated by prestige television shows such as Breaking Bad, Succession, Game of Thrones, and White Lotus. But the reality is, shows like Gray’s Anatomy, NCIS, and, yes, Suits, are the shows that truly get the ratings. Just not the love.

I decided to find out for myself if Suits was worthy of all the hype or if it was merely a curiosity brought about by the world’s obsession with Megan Markle (who plays a major character on the show). What follows are my thoughts.

Suits is set in New York City and follows a law firm led by Jessica Pearson, who’s trying to figure out if she should hand the firm down to her best lawyer, Harvey Specter. The problem is Harvey (a young George Clooney doppelgänger) is an arrogant blowhard who only cares about himself.

Harvey is on the lookout for a new lawyer, which is where Mike Ross comes in. Mike is a super-genius who’s had his life derailed by a couple of bad decisions and is in such a bad place that he actually agrees to deliver a suitcase full of drugs for money (that he plans to use for his sick grandmother, of course).

Mike goes to a hotel to make the drop but susses out that he’s being set up and makes a run for it… right into Harvey’s lawyer interviews. Mike stumbles his way into Harvey’s office where he accidentally opens the suitcase and all the drugs fall out.

Intrigued, Harvey asks Mike why he has a suitcase full of drugs and Mike tells him the truth. Further discussions lead Harvey to learn that Mike is beyond a genius and could run circles around all the Harvard applicants in the lobby. The kid is so raw, Harvey almost turns him away. But, in the end, he decides to take a chance on him. This leads to Mike’s first big case, a sexual harassment lawsuit.

Let’s cut to the chase.

Good writing is good writing is good writing.

It’s what I always tell people. Good writing prevails above all. It is almost impossible to find something that’s well written and completely ignored. Because good writing is rare. So when it arrives, it tends to birth a good product.

When it comes to TV, there are three writing ingredients that must thrive. The characters, the dialogue, and conflict. If you are good at these three things, you will be good at writing for television.

Cause TV isn’t so much about plot. Especially episodic shows like this one (case of the week). Plot is more for movies. The reason for that is, a movie needs a conclusion. And that’s where plot leads us. It gives us a goal and then, at the end of the story, we either succeed or fail at achieving that goal.

TV doesn’t need to end. It keeps going. So while there is plot in each individual episode (try to win the case), the plots are devoid of the kind of stakes that really matter. Cause who cares if Harvey and Mike win this week’s sexual harassment case? There’s going to be another one, just like it, next week.

For that reason, audiences come to TV shows more to hang out with the characters. Which is why all your TV writing should start with creating great characters.

Mike is a perfect character. Why? Two reasons. He’s an underdog and he’s super smart. These are two things that audiences DIE FOR. They love underdogs more than anything. This guy who didn’t even graduate law school being thrown into one of the biggest firms in New York — we love watching sh*t like that.

On top of that, audiences love characters who are smarter than everyone. There’s an early scene where Mike sniffs out that two men in the hallway (pretending to look like a bellhop and a guest) may be cops and he’s been set up with this drug delivery. So he asks the bellhop, “Hey, I was thinking about taking a dip later. How’s the pool here?” “It’s one of the best in the city, sir. You’ll love it.” Then we do a quick flashback of Mike earlier walking past the pool and a sign that says, “Pool closed for the summer.”

So we immediately know that Mike is smart. He uses his power of observation to stay ahead of everyone.

Then you have Harvey. I still don’t know exactly what the line is between hateable a$$hole and lovable a$$hole, but I know that audiences love lovable a$$holes. As long as the a$$hole is on our side.

One trick I’ve learned is to put our lovable a$$hole in the room with people who are worse than him. There’s an early scene where a client tries to railroad Harvey for not getting him everything he wants in their deal. But Harvey stays calm and outsmarts the guy, winning the conversation. In other words, if your hero is a bully and you want to make him likable, just add a bigger bully.

When it comes to dialogue, one thing I’ve noticed that these episodic TV shows live by is metaphors. They’re always using metaphors in the dialogue, which helps make the dialogue clever.

So, in the above scene where the client yells at Harvey, Harvey takes out a receipt of funds transferred and tells the guy that any threat to terminate their contract doesn’t matter because the firm has already received his money. The guy huffs out and it’s revealed that the piece of paper was a pointless memo. Harvey was lying.

Harvey’s boss then asks him, “How did you know he wouldn’t look closer and realize you were lying?”

Think for a second how you would write Harvey’s response. Because most beginner writers would write something like, “He’s a bully. And bullies never look closely at the details.”

It’s a lame lifeless line.

Here’s the line that Harvey actually uses in the pilot: “Cause a charging bull always looks at the cape, never the man with the sword.”

Now, is this the most brilliant line in the world? No. But it’s better than, “He’s a bully. And bullies never look closely at the details.” The metaphor automatically upgrades the line into something with more pop.

With TV, you really have to be on your dialogue game. If you are not a dialogue person, definitely stay away from this medium. It’s easier to get away with a lack of dialogue prowess in features because features are more plot driven, depend on exposition more (which is more technical), and are more about showing as opposed to telling. So you don’t have to write as much dialogue if you don’t want to.

Finally, we have conflict. Conflict is very simple to create. You put two people in a room who don’t see eye-to-eye, either about what’s happening in the moment, or in how they view the world in general. Or you give characters little goals and then throw obstacles in front of those goals.

The reason obstacles are great is not just to create conflict – which they do – but because they give your characters opportunities to shine, which is both entertaining and make us like the character more.

So that moment where Mike walks up in the hotel hallway and sees the bellhop and the fake guest — that’s an obstacle. Notice how Mike using the “is the pool open” bait shows him dealing with the obstacle in a clever way, which makes us like him more. The cops-in-disguise then chase him, which is where the conflict comes from.

Also, in the very next scene, when Mike interviews with Harvey, there’s conflict in that scene as well. Harvey clearly likes Mike. But he can’t hire someone who hasn’t even graduated law school. So there’s this tug-of-war where he challenges Mike with a series of problems that Mike passes one by one. Mike eventually wins him over and the conflict is resolved.

So if you’re good at these three things – character, dialogue, conflict – you can be a TV writer. And Suits is a great show to study for how to do it right.

[ ] What the hell did I just stream?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the stream

[x] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: I don’t know if there’s a better setup than taking someone who’s perceived as “not intelligent” (or who has street smarts, or who does things differently than you’re supposed to) and putting them in a scenario where they’re competing against the “smartest people in that industry.” It’s built perfectly for us to feel a sense of satisfaction every week when our supposedly “dumb” hero outsmarts the “smart” guys once again.

I’ve got a big fat juicy newsletter that’s going to get you salivating over screenwriting in a way that’s illegal in Canada. We’ve got the surprise September Showdown announcement. We’ve got a nuanced conversation about how many scripts you should be writing. I take on Ahsoka (and the Star Wars brand along with it). I ask the question we’ve all been wondering: Is Keanu Reeves a secret screenwriting genius? There are a couple of new trailers out that caught me by surprise. The new guard of filmmakers and artists has definitely arrived. But is the old guard ready to give up their seats?

If you’re not on my newsletter list, e-mail me at carsonreeves1@gmail.com and I’ll put you on!